Donald Trump’s plan to lower prescription drug prices, announced May 11 in the Rose Garden, is a wonky departure for the president. In his approach to other signature campaign pledges, Trump has selected blunt-force tools: concrete walls, trade wars, ICE raids. His turn to pharmaceuticals finds him wading into the outer weeds of the 340B Discount program. These reforms crack the door on an overdue debate, but they are so incremental that nobody could confuse them with the populist assault on the industry promised by Trump the candidate, who once said big pharma was “getting away with murder.”

With his May 11 plan, Trump is, in effect, leaving the current pharmaceutical system in place. Increasingly, its most powerful shareholders are the activist managers of the hedge funds and private equity groups that own major stakes in America’s drug companies. They hire doctors to scour the federal research landscape for promising inventions, invest in the companies that own the monopoly licenses to those inventions, squeeze every drop of profit out of them, and repeat. If they get a little carried away and a “price gouging” scandal erupts amid howls of public pain and outrage, they put a CEO on Capitol Hill to endure a day of public villainy and explain that high drug prices are the sometimes-unfortunate cost of innovation. As Martin Shkreli told critics in 2015 of his decision to raise the price of a lifesaving drug by 5,000 percent, “this is a capitalist society, a capitalist system and capitalist rules.” That narrative, that America’s drug economy represents a complicated but beneficent market system at work, is so ingrained it is usually stated as fact, even in the media. As a Vox reporter noted in a piece covering the May announcement of Trump’s plan, “Medicine is a business. That’s capitalism. And we have seen remarkable advances in science under the system we have.”

This is a convenient story for the pharmaceutical giants, who can claim that any assault on their profit margins is an assault on the free market system itself, the source, in their minds, of all innovation. But this story is largely false. It owes much to the rise of neoliberal ideas in the 1970s and to decades of concerted industry propaganda in the years since.

In truth, the pharmaceutical industry in the United States is largely socialized, especially upstream in the drug development process, when basic research cuts the first pathways to medical breakthroughs. Of the 210 medicines approved for market by the FDA between 2010 and 2016, every one originated in research conducted in government laboratories or in university labs funded in large part by the National Institutes of Health. Since 1938, the government has spent more than $1 trillion on biomedical research, and at least since the 1980s, a growing proportion of the primary beneficiaries have been industry executives and major shareholders. Between 2006 and 2015, these two groups received 99 percent of the profits, totaling more than $500 billion, generated by 18 of the largest drug companies. This is not a “business” functioning in some imaginary free market. It’s a system built by and for Wall Street, resting on a foundation of $33 billion in annual taxpayer-funded research.

Generations of lawmakers from both parties bear responsibility for allowing the drug economy to become a racket controlled by hedge funds and the Martin Shkrelis of the smaller firms. The current crisis in drug prices and access—as well as a quieter but no less serious crisis in drug innovation—is the result of decades of regulatory dereliction and corporate capture. History shows there is nothing inevitable or natural about these crises. Just as the current disaster was made in Washington, it can be unmade in Washington, and rather quickly, simply by enforcing the existing U.S. Code on patents, government science, and the public interest.

In 1846, a Boston dentist named William Morton discovered that sulfuric ether could safely suppress consciousness during surgery. The breakthrough revolutionized medicine, but when Morton filed a patent claim on the first general anesthesia, one doctor huffed to a Boston medical journal, “Why must I now purchase the right to use [ether] as a patent medicine? It would seem to me like patent sun-light.”

The response reflected a longstanding belief that individuals shouldn’t be able to claim monopolies on medical science. Breakthrough discoveries, unlike the technologies inventors would design to apply those discoveries, should remain open and free to a global community of doctors and researchers, with the backing of the government if necessary.

These norms persisted into the postwar era. In 1947, U.S. Attorney General Samuel Biddle argued that the government should maintain a default policy of “public control” over patents. This, he said, would not only advance science, public health, and marketplace competition, it would also avoid “undue concentration of economic power in the hands of a few large corporations.” When asked on national television in 1955 why he didn’t patent the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk famously borrowed the quip leveled a century earlier against the Boston dentist who invented ether. “Could you patent the sun?” he asked.

By then, though, the economics of medicine had begun to shift, and with them the medical ethics surrounding patents. The public university at that time had become a giant laboratory where government and industry scientists worked together designing missiles, inventing medicines, and engaging in basic-science futzing under the “Science of the Endless Frontier”—a concept promoted by New Deal science-guru Vannevar Bush, who believed that the government should fund the open-ended pursuits of the most gifted scientists. Out of this new world arose new interests and new questions: What happens to the inventions spinning out of government-funded labs? Who owns them, who can license them, and for how long?

Toward the end of the 1960s, new mechanisms hatched out of the National Institutes of Health would transform the industry and drastically expand the opportunities for private profit at the expense of the public interest, ushering in a post-Biddle age of virtually unrestricted industry access to taxpayer-funded science.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the patent is more than just the product. It is a license to print money. An awful lot of money.In 1968, the NIH’s general counsel, Norman Latker, spearheaded the revival and expansion of a program that had, in the years before the government spent much on science, permitted nonprofit organizations—universities, mainly—to claim monopolies on the licenses of medicines developed with funding from NIH. Called the Institutional Patent Agreement program, it effectively circumvented rules that had been in place since the 1940s, not only making monopolies possible, but also greatly expanding their terms and limits, giving birth to a generation of brokers whom universities relied on to negotiate newly lucrative exclusive licensing and royalty deals with pharmaceutical companies.

In an industry where active ingredients are often bulk-purchased for pennies and sold in milligrams for dollars, the patent is more than just the product. It is a license to print money. An awful lot of money.

Before 1968, inventors had been required to assign any inventions made with NIH funding back over to the federal government. Now, those inventions were being sold to the highest bidder. “Nineteen-sixty-eight was the year the NIH threw its support behind a drug development market based on patent monopolies,” says Gerald Barnett, an expert on public-private research who has held senior licensing positions at the University of Washington and University of California. “It’s kept it there ever since.”

Watching these developments closely was the group of nominally libertarian economists, business professors, and legal scholars at the University of Chicago, known collectively as “The Chicago School.” The industry’s regulatory travails and the new opportunities to commercialize science that had emerged in the late 1960s were of particular interest to the economist George Stigler, a founding member of the Chicago School and its most celebrated theorist after Milton Friedman. Stigler is remembered today as the father of “capture theory,” which holds that because industries have a bigger stake in policy than individual citizens, they will exert greater control over shaping that policy. Industry, he argued, will seek to use their power to hamper competition and shore up their position in the market. Regulation never benefits the public, he believed; instead, it benefits the very industry being regulated. There is a lot of merit in this theory. But instead of arguing for more democratic control over regulation, Stigler argued for its elimination.

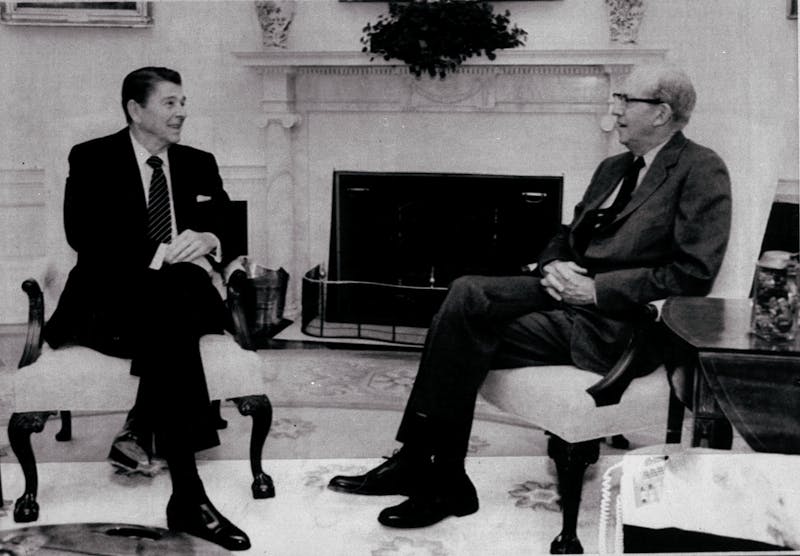

George Stigler meets with Ronald Reagan at the White House in 1982. Stigler’s work on “regulatory capture” provided the ideological backbone for the new pharmaceutical order. Getty

George Stigler meets with Ronald Reagan at the White House in 1982. Stigler’s work on “regulatory capture” provided the ideological backbone for the new pharmaceutical order. GettyThough members of the Chicago School opposed monopolies, Stigler and his colleagues hated the government, not to mention the burgeoning “consumer-rights” pro-regulation movement of the 1970s, even more. If forced to choose between private and public power, there was no contest. Stigler developed his openly un-democratic ideas as chair of the Business School’s Governmental Control Project, whose name reflected a double meaning at the core of the project it served: Advancing the “free market” against government control of the economy can be achieved not only by rolling back the state and eliminating its agencies (the approach Milton Friedman favored—and promoted in the Newsweek column he wrote between 1966 and 1984), but by the invasion and colonization of politics on multiple fronts, especially patent law, regulation, and antitrust and competition policy.

“Pharma was the perfect test case for a neoliberal project that celebrates markets, but is fine with large concentrations of power and monopoly,” says Edward Nik-Khah, a historian of economics who studies the pharmaceutical industry at Roanoke College. “Stigler and those influenced by his work had very sophisticated ideas about how to audit and slowly take over the agencies by getting them to internalize [their] positions and critiques. You target public conceptions of medical science. You target the agencies’ understanding of what they’re supposed to do. You target the very thing inputted into the regulatory bodies—you commercialize science.”

“Pharma was the perfect test case for a neoliberal project that celebrates markets, but is fine with large concentrations of power and monopoly.”In 1972, Stigler organized a two-day event, “The Conference on the Regulation of the Introduction of New Pharmaceuticals.” Major drug makers like Pfizer and Upjohn pledged funds and sent delegates to the conference—a first and fateful point of contact between Pharma and the organized movement to undo the New Deal and radically remake the U.S. economy to serve an ideology of unfettered corporate power.

Born of this meeting was the echo chamber of ideas, studies, and surveys that the pharmaceutical industry has used to buffer an increasingly indefensible system against regular episodes of public outrage and political challenge. Organized and initially staffed by alumni of the Chicago conference, its hubs are the American Enterprise Institute’s Center for Health Policy Research, founded 1974, and the Center for the Study of Drug Development, founded in 1976 at the University of Rochester and later moved to Tufts. Their research has succeeded in producing and policing the boundaries of the drug pricing debate, most successfully propagating the myth that high drug prices are simply the “price of progress”—carrots that drug manufacturers need to entice them to sink hundreds of millions into research and development, because drugs cannot be developed or tested any other way. In the early 2000s, these think tanks gave us the deceptive meme of the “$800 Million Pill,” a dubious claim about the “real” cost of developing a single drug, which has provided cover for, among other things, George W. Bush to sign away the government’s right to negotiate drug prices in 2004. (The same think tanks now talk about the “$2.6 Billion Pill.”)

“The point of pharma’s echo chamber was never to get the public to support monopolistic pricing,” says Nik-Khah. “As with global warming denialism, which involves many of the same institutions, the goal is to forestall regulation, in this case by sowing confusion and casting doubt about the relationship among prices, profits, innovation and patents.”

While Stigler was marshaling researchers in the think tank world, the market was evolving to include more opportunities for speculative investments and bigger IPOs. Venture capital firms in the 1970s began investing heavily in biotech; soon, young biotech firms, established drug makers and Wall Street were pushing for changes in licensing and patent law to make these investments more profitable. They were aided in this by Edward Kitch, a law professor, Chicago School protégé of Richard Posner, and veteran of the ’72 conference, who worked with AEI’s Center for Health Policy Research. In 1977, he published “The Nature and Function of the Patent System” in The Journal of Law and Economics. It enumerated the many advantages of patents and IP rights, not least their role as bulwarks against the “wasteful duplication” of competition. Patents create the conditions for increased profits that, in turn, increase private sector R&D and spur innovation. (If this sounds familiar, it’s because the paper helped press the record for what has since become the industry’s favorite tune, “Price of Progress,” sung over the years in a thousand variations, including the strained aria of Michael Novak’s Pfizer-funded essay on the moral and Godly bases of monopoly patents, The Fire of Invention, The Fuel of Interest.)

These efforts contributed to a revolution in biomedical IP law during the Carter and Reagan years. The cornerstone of the new order was the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act of 1980, better known as Bayh-Dole. Drafted in 1978 by the NIH’s counsel Norman Latker (previously seen drafting the IPA regime in 1968), the Act gave NIH contractors new powers over the ownership and licensing of government science, including a right to issue 17-year life-of-patent monopolies—a change former FDA Commissioner Donald Kennedy has compared to the Enclosure and Homestead Acts that privatized the English countryside and the American West. (Latker, for his part, would continue to defend the bill he’d helped craft years later. In 2004, now retired, he told Congress that any attempt to reassert government controls on drug prices would be “intolerable.”)

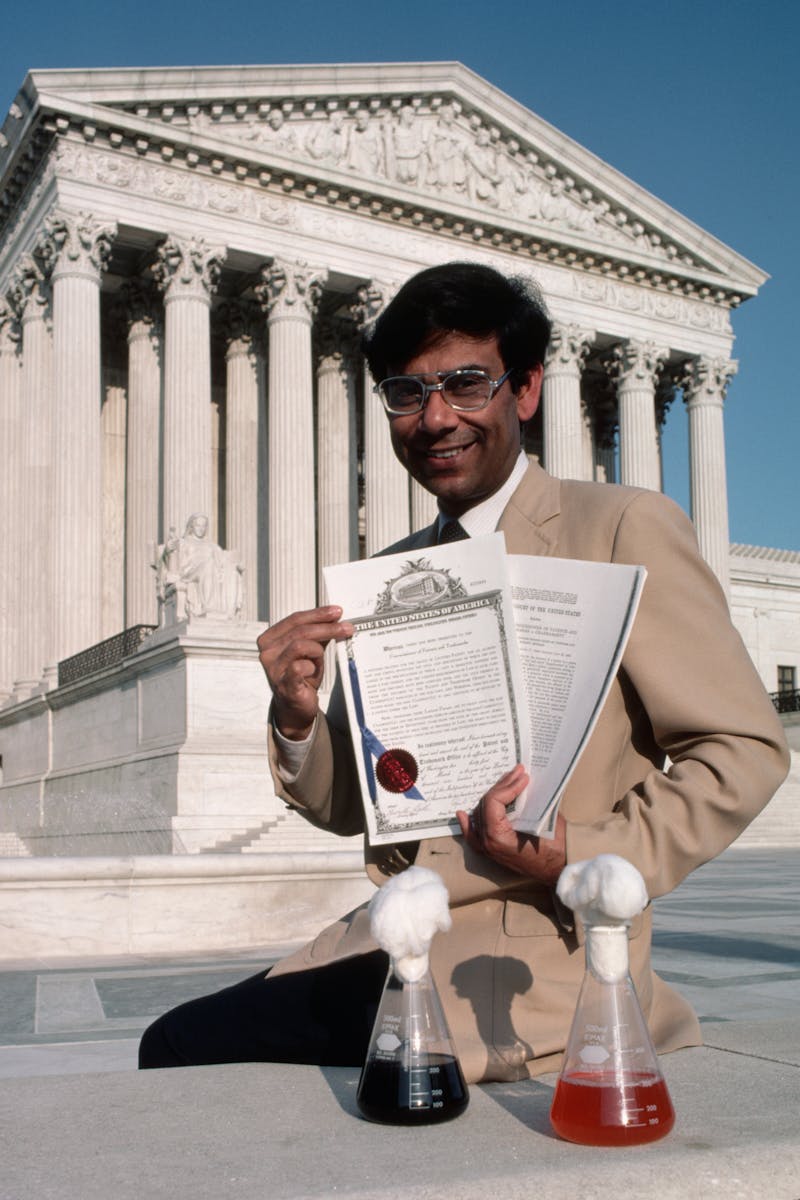

Ananda Chakrabarty shows off copies of the Supreme Court’s 1980 decision to let him patent genes and genetically engineered organisms, as well as the patent itself. The ruling would fuel a gold rush in biotech. Ted Spiegel//Corbis /Getty

Ananda Chakrabarty shows off copies of the Supreme Court’s 1980 decision to let him patent genes and genetically engineered organisms, as well as the patent itself. The ruling would fuel a gold rush in biotech. Ted Spiegel//Corbis /GettyShortly after the passage of Bayh-Dole, the Supreme Court in 1980 decided a GE scientist named Ananda Chakrabarty could patent genes and genetically engineered organisms, fueling a gold rush in biotech and further sweetening pharma as a destination for investors. “The Chakrabarty decision provided the protection Wall Street was waiting for, encouraging academic entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to explore commercial opportunities in biotech,” says Oner Tulum, who studies the drug sector at the Center for Industrial Competitiveness. “It was the game changer that paved the way for the commercialization of science.”

Presidents from Reagan through Clinton continued to push legislation friendly to pharmaceutical manufacturers. The 1983 Orphan Drug Act provided extended licenses and tax waivers on drugs targeting rare and genetic diseases. A 1986 tech transfer bill established “Cooperative Research Centers” that gave industry a direct presence in federal labs, and established offices to assist in transferring the fruit of these labs to their new commercial partners. Under Clinton, who would consistently expand private access to government research, the FDA Act of 1997 opened the era of direct television drug marketing.

By the early 1990s, a new monster had emerged: an emboldened, triumphant, and fully financialized Pharma. It would help defeat Bill Clinton’s health reforms and go on to reshape the industry, not as something geared toward public needs, the high-risk development of breakthrough drugs, or even long-term profitability, but as a business focused narrowly on predatory value extraction: scooping up government-funded science, gaming the system to extend licenses and delay generic competition, and aggressively seeking short-term stock boosts through maximum pricing, mergers, acquisitions and takeovers.

To understand financialized pharma, just look at what it does with its money. Drug companies have spent the vast majority of their profits in recent years on share buybacks that maximize immediate share value. Donald Trump’s 2017 tax bill, for example, allowed drug makers to repatriate more than $175 billion banked offshore at giveaway rates. Most of this money, including $10 billion by Pfizer alone, was spent on buybacks and cash dividends to public shareholders, which increasingly include hedge funds. Meanwhile, R&D expenditures stayed flat or fell across the industry.

This is the backstory to every drug pricing scandal in memory. Between 2013 and 2015, companies owned in part by hedge funds, private equity, or venture capital firms produced 20 of the 25 drugs with the fastest-rising prices. Occasionally their role in price-gouging has received public attention. In 2015, for example, Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Fund oversaw flagrant price-inflation schemes at Valeant as part of a failed takeover of Allergen. But usually the involvement of hedge funds in price hikes goes unnoticed.

Consider the case of Mylan’s EpiPen. In 2015, Mylan controlled more than 90 percent of the country’s epinephrine injector market, with a decade left on its patents. The company’s lock on a large market with inelastic demand was chum for hedge funds; a half-dozen, notably the New York investment management firm Paulson & Company, bought stakes in the company. Mylan then started spiking the price on EpiPens, swelling revenues and inflating share price. It raised more than $6 billion off this bold display of pricing power and used the money to fund a takeover of the Swedish company Meda, just as an EpiPen two-pack hit $600. The cost of manufacturing EpiPens, meanwhile, hung steady at a few dollars, as did the sticker price of EpiPens in Europe, where regulation keeps them as low as $69.

Public outrage, most of it targeting the CEO, ensued; Hillary Clinton even tweeted about it on the campaign trail. But for Mylan, the only audience that mattered was its industry peers and Wall Street.

When Gilead charged six figures for a new Hepatitis C drug, hedge fund manager Julian Robertson called the price “fabulous,” and shares in the company “a pharmaceutical steal.”“Dramatically increasing prices is a honey pot for investors,” says Danya Glabau, a medical anthropologist and former biopharmaceutical consultant who has written about the EpiPen scandal. “The public expects that drug prices recoup R&D investments based on science and patient needs. But they’re shows and aspirational signals for an investor audience watching every move.”

Gilead Sciences’ new Hepatitis C drugs are another example. Although the drugs were developed in a NIH-funded lab at Emory University, Gilead was able to set the price at six-figures, leading to extreme Medicaid rationing and effectively sentencing millions of Americans to early deaths. Hedge fund manager Julian Robertson, whose Tiger Management holds an activist stake in Gilead, called the price “fabulous,” and shares in Gilead “a pharmaceutical steal.” Those drugs alone accounted for more than 90 percent of the company’s nearly $28 billion in revenues in 2016, according to its annual report.

Pricing scandals like these are often burned into the public mind with indelible images: Martin Shkreli smirking on cable news about jacking the price of Daraprim 5,000 percent, or Mylan chairman Robert Coury raising both middle fingers in a board meeting, and telling the parents of kids with serious food allergies to “go fuck themselves” if they can’t afford his $600 EpiPen two-pack. But such images tell only half the story. These scandals, and the profits they net, aren’t the work of a few “bad actors.” They are only possible because of the monopoly patent pipeline and unregulated pricing regime established and overseen by the United States government.

Although the public is constantly being lectured about the horrible “complexity” of drug pricing, solutions to the drug access crisis have been hiding in plain site for decades, in the plainly stated public interest rules attached to Bayh-Dole. These rules clearly state that the “utilization and benefits” of science developed with public funds be made “available to the public on reasonable terms.” The government not only possesses the power to directly control drug prices in the public interest—it is obliged to do so, as a condition of allowing industry access to taxpayer funded science. The government possesses the power to reduce the price on any drug it sees fit—known as “march-in rights”—and has long possessed this power.

“When Bayh-Dole created a monopoly patent pipeline from universities to the pharmaceutical industry, it also created an apparatus to protect the public from the ill effects of those monopolies,” says Gerald Barnett, the licensing expert, who maintains a blog on the history of government tech transfer.

“The law restricts the use of exclusive licenses on inventions performed in a government laboratory and owned by the government,” said Jamie Love, the director of Knowledge Ecology International, a D.C.-based nonprofit organization that works on access to affordable medicines and related intellectual property issues. “Before an exclusive license is even offered, the government must ask: Is the monopoly necessary? Whether an invention is done at the NIH or UCLA, there is also an obligation to ensure the drug is available to the public on reasonable terms.”

Of course, a long run of NIH administrators, answering to a long run of Secretaries of Health and Human Services, have chosen to ignore these requirements. “The NIH refuses to enforce the apparatus because it wants the pipeline,” Barnett said. “The lack of political will suggests the industry has bought everyone off.”

In 2017, Pharma spent $25 million lobbying Congress, up $5 million from the previous year. Among trade groups, only the National Association of Realtors and the Chamber of Commerce spent more. This has not only fostered cozy relationships between industry and Congress, but also the private sector and the NIH. In 2016, for example, at Davos, the oncologist-entrepreneur Charles Sawyers and serving NIH director Francis Collins took chummy selfies together at an announcement of Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot.

“When we saw those pictures, we knew we were screwed, and we were,” said Love of Knowledge Ecology International. “The government is ignoring its own directives and allowing people to die.”

“The government is ignoring its own directives and allowing people to die.”This has left activists with one option: legal action. Love’s group and others have been challenging NIH, as well as researchers like Collins, in court. In April, Love’s group filed a civil action in Maryland district court against the NIH, Collins, and the National Cancer Institute, seeking an injunction against the licensing of a new immunotherapy drug developed by NIH scientists to a subsidiary of Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Love notes that there are multiple legal mechanisms on the books the government could use to drive down the cost of drugs. Along with powers enumerated in the fine print of Bayh-Dole, it can invoke Title 28 Section 1498 of the U.S. Code, which grants the government power to break patents and license generic competition in the public interest. In return, it is obliged only to provide “reasonable compensation” to the patent holder, which the government could, in the case of a price-gouging drug company, define as a platter of cold mayonnaise sandwiches. (In practice, it would likely be a bit more. During the Vietnam War, the Pentagon’s Medical Supply Agency used 1498 to procure the antibiotic nitrofurantoin for a “reasonable” reimbursement of 2 percent of the company’s sticker price.)

Is there any chance that Alex Azar, of all people, could be the first HHS chief to keep these long-ignored promises to the public? The former Eli Lilly executive does not cut the profile of people’s champion. It’s difficult to think of anyone in the current administration who does. And yet, Azar has raised the issue of patent abuses, and made noises about enforcing existing laws to stop drug makers from gaming the system and suppressing generic competition. Though unlikely, it’s not inconceivable this campaign could, if supported by enough public pressure, grow to include championing Bayh-Dole’s public interest provisions more broadly.

Whether this administration tries to solve the drug crisis, or leaves it for a future administration, any real fix will require rejecting the myth that controlling prices stymies innovation by cutting into bottom lines. The industry’s enormous profits since the 1970s—the fattest margins, in fact, of the entire U.S. economy—increasingly bear little relation to the amount it invests in R&D, and the government underwrites much of the most important research, anyway. Medicine isn’t “a business,” and the current public-private mutant beast of a system isn’t the only one capable of developing new drugs. These myths persist because of the longtime supremacy of free-market ideology in our political system, which helps explain the media’s predictable gushing over plans like MIT professor Andrew Lo’s proposal to finance the high cost of drugs, drug development and healthcare with securitized loans. (“Can Finance Cure Cancer?” a PBS Newshour segment asked in February.) Finance is the problem, and Washington alone holds the keys to the solution. Only when Americans come to terms with that, and have a government eager to act on it, will they be in position do something about the industry the president has rightly described as murderous.

On May 10, 1869, the transcontinental railroad linked America from east to west for the first time in history. It was a formidable undertaking: Over the course of six years, more than 10,000 workers built the tracks by hand in treacherous conditions. In an historic photograph marking the railroad’s completion, the men who had been involved assembled around two locomotives to celebrate the final spike. Over 80 percent of the laborers were migrants from China—and yet, not one man pictured is Chinese.

THE CHINESE MUST GO: VIOLENCE, EXCLUSION, AND THE MAKING OF THE ALIEN IN AMERICA by Beth Lew-WilliamsHarvard University Press, 360 pp., $39.95

THE CHINESE MUST GO: VIOLENCE, EXCLUSION, AND THE MAKING OF THE ALIEN IN AMERICA by Beth Lew-WilliamsHarvard University Press, 360 pp., $39.95The staged photograph is an eerie artifact of the growing anti-Chinese sentiment of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, which culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Scott Act of 1888. As Beth Lew-Williams shows in her new book The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America, Chinese immigration to the United States was far from unwelcome to begin with: For U.S. politicians, missionaries, and businessmen in the 1850s, Chinese migration was a part and a parcel of American advancement in the China Trade. The influx of Chinese workers, prompted by political and economic instability following the First Opium War, provided labor for a growing U.S. economy; at the same time the movement of laborers, merchants, scholars, and missionaries between the United States and China strengthened relations between the two countries.

The ties that American expansionists embraced, however, angered white settlers in the American West. They believed Chinese migrants drove wages down, threatening the independence and self-sufficiency of white workers. They saw Chinese migrants as unassimilable because they refrained from American habits of consumption—they “did not eat red meat, buy books or nice clothes, engage in leisure,” so the stereotype went—and they didn’t appear to support dependents in the United States, instead sending their pay home to families in China. Many whites feared that the very presence of Chinese migrants would rock the foundations of the American republic. Drawing from diaries, official documents, and speeches, Lew-Williams wryly summarizes their reasoning that “while an authoritarian state” might be able to “subjugate” a minority, “a republic, it was believed, required a homogenous citizenry to survive.”

But it took a lot more than this mass of prejudice to make anti-Chinese sentiment a matter of national policy. Those policies would have far-reaching effects that extend to the present: The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Scott Act of 1888 destroyed all but pre-existing Chinese communities for nearly six decades. While it failed to actually end Chinese migration, it simultaneously barred Chinese people in the United States from naturalization and encouraged continued abuse of Chinese workers. It’s the development of this policy and its legacy that Lew-Williams has studied, tracing how white supremacist interests constructed modern notions of citizens and aliens.

Before exclusion came several attempts at limiting Chinese migration, each responding to widespread anti-Chinese sentiment among whites in the United States—99 percent of California voters, an 1879 ballot showed, were against Chinese migration. Chinese workers suffered violence and harassment, as well as organized political opposition. Leaders such as Dennis Kearney of the Workingmen’s Party of California and Daniel Cronin of the Washington Territory’s Knights of Labor exploited existing Sinophobia to position the anti-Chinese movement as “peaceful” advocacy for workers rights. Even as they claimed that they were nonviolent, they leveraged the threat of violence to pressure Congress into considering Chinese exclusion.

Split between honoring diplomacy with China and preserving order at home, Congress made a series of tepid compromises. To maintain a semblance of limiting migration, in 1875 Congress passed the Page Act, which limited the migration of Chinese women. The United States also negotiated a reversal of prior treaty stipulations to allow American officials, for the first time, to regulate the migration of Chinese workers. Then, in 1882, in response to deepening concerns of white violence, Congress passed the “Chinese Restriction Act,” now known as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

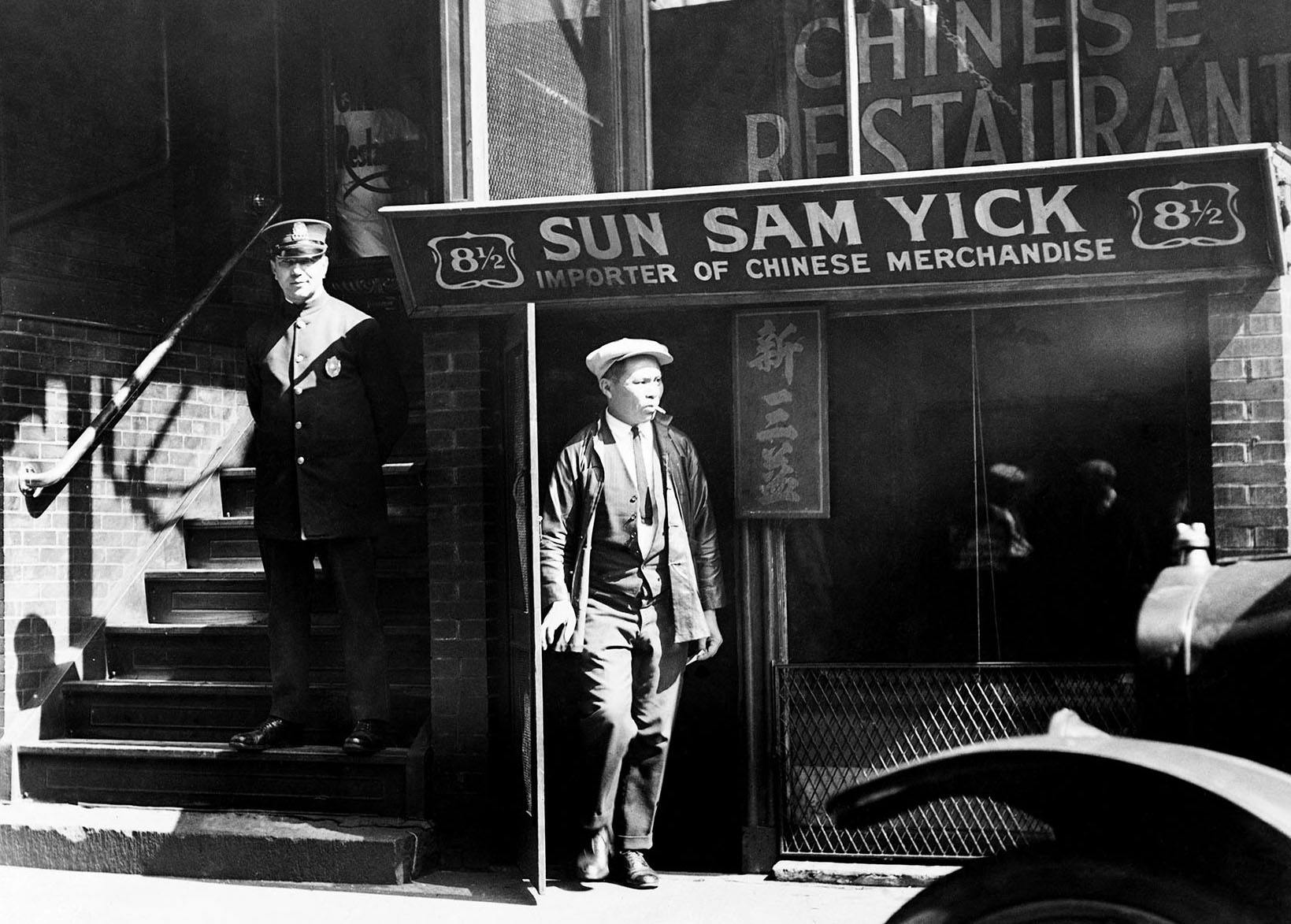

By preventing new workers from entering and barring existing residents from naturalization, the Act further crystallized distinctions between citizens and aliens, stoking existing racism, economic anxiety, and xenophobia. Local officials faced the impossible task of regulating the San Francisco harbor and the extensive border between U.S. territories and Canada. Consequently, they turned to white townspeople in San Francisco and the Washington Territory to report on their neighbors and co-workers. This form of border control proved unreliable, as the white townspeople tended to target Chinese workers indiscriminately, which in turn exacerbated racial tensions in previously integrated neighborhoods and workplaces. When violence broke out and officials failed to condemn it, they effectively recognized white vigilantes as extensions of federal and state border regulation.

Especially in the Pacific Northwest, where white locals couldn’t yet vote in national elections, the movement’s leaders justified racial violence as a valid form of political action. The federal government did little to discourage them. During the Rock Springs Massacre of 1885 in the Washington Territory, white miners killed 28 Chinese workers, wounded 15, and forced out hundreds before they set Chinese living quarters on fire. Emboldened by news reports of the incident, white vigilantes in Tacoma banded together with city officials to announce the “peaceful” and “business-like” removal of Chinese residents.

American commercial expansion and white nationalism were no longer mutually exclusive—they were now entirely compatible.Though Tacomans would make death threats, loot and burn down homes, and drive out all but one Chinese resident, anti-Chinese editorial staff on the LA Times and Tacoma Daily News, among other local papers in the West, wrote up the episode as a successful, non-violent blueprint for Chinese expulsion. The “Tacoma method” would inspire vigilante expulsions of Chinese communities all over the West Coast and Pacific Northwest; by Lew Williams’s tally, over 200 cities and towns saw similar incidents between 1885 to 1887.

Concerned about the spread of anti-Chinese violence in the United States and anxious to prevent a mass return of migrants, Chinese officials proposed in 1886 to ban Chinese laborers from leaving China if they intended to move to the United States. Simultaneously, Congress came under pressure to resolve the “Chinese Question” before an upcoming election. Instead of addressing intensifying violence, U.S. lawmakers saw the Chinese self-ban as a convenient opportunity to extend the 1882 legislation; in 1888 the Scott Act passed, stipulating that even Chinese workers with valid return certificates could not re-enter the United States. American commercial expansion and white nationalism were no longer mutually exclusive—they were now entirely compatible.

The legislation formulated during this period paved way for the systematic surveillance of Chinese and other Asian immigrants in the United States. In 1892, the Geary Act required all Chinese migrants to undergo a registration system and provide “affirmative proof” of their right to reside on U.S. soil. This was unheard-of at the time. The registration system “effectively transformed the Chinese Exclusion Act into a Chinese expulsion act by targeting long-term residents,” Lew-Williams writes. “Border control was no longer confined to the nation’s borders but stretched into the interior.”

Exclusionary policy drove migration underground, increased human trafficking, and added to the physical and psychological dangers that already accompanied the journey. Violence and exclusion not only continued within the United States, but also overseas in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, following the end of the Spanish-American War. Chinese communities—some of which had existed in integrated neighborhoods and workplaces—were forced into hyper-segregated enclaves, while some individuals were cut off from their communities altogether and scattered among hostile, white-dominated areas across the country. Even decades after Chinese Exclusion ended in 1943, the effects are marked: Less than 10 percent of Chinese-Americans today can trace their lineage back three generations in the United States. In Tacoma, a decade-long search for descendants of the Tacoma Chinese has yielded none.

In Tacoma, a decade-long search for descendants of the Tacoma Chinese has yielded none.The majority of Chinese in America today arrived along with other East Asians, South Asians, and Southeast Asians after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which remade the socioeconomic and ethnic makeup of Asians in America by prioritizing family reunification and skilled workers. The influx of upwardly mobile immigrants became an opportunity for both conservatives and liberals to retire the “yellow peril” stereotype and recast Asian Americans as “successful immigrants,” politically amenable and capable of assimilating into white, middle-class America. Many Asian Americans, who had been stigmatized as communist infiltrators during the Red Scare of the ’50s, also promoted the model minority narrative to avoid further exclusion and violence. The careful fabrication of Asian success has in turn been used both to justify racism against other minorities and to erase socioeconomic and generational differences within Asian American communities.

The model minority myth does not reflect the broader history of Asians in the United States, from the 60-year-long history of Chinese exclusion, to Japanese incarceration, to the radical Asian American movement. This history is vital, but very little of it is taught in schools: A 2015 survey of American government textbooks revealed that on average, Asian American and Pacific Islander issues made up less than 1 percent of the pages. If current first- and second-generation Asian Americans are estranged from the decades-long history of Chinese exclusion, that distance, too, has been constructed by white violence, federal failure, exclusionary policy—and by continued historical erasure.

Today, Asian American communities are the fastest growing populations in the United States, but have some of the lowest voter turnout rates compared to other minorities. Increased outreach and accessible translated ballots will be crucial to mobilizing Asian Americans as a political force, but meaningful civic engagement begins first with historical and political understanding. It will be increasingly necessary for Asian Americans to consider the historical roots of structural inequalities that continue to shape America. That means not only breaking down historical and present-day stereotypes, but learning to see what is missing from pictures of the past.

GLOW’s second season opens with Ruth Wilder (Alison Brie) posing for a photo to mark the day she and her costars on the women’s wrestling circuit begin filming. For Ruth, this is a solemn moment; Gorgeous Ladies Of Wrestling has represented her path toward a bigger sort of life, the only one available to her, or so she believes. When her fellow wrestlers see her posing, they try to get into the picture themselves. This collective celebration of a new beginning is as it should be: Ruth came to GLOW alienated, sexually self-destructive, and utterly broke at the beginning of the first season, and found not only professional sustenance, but also a lifeline—friends.

Distributed by Netflix, this celebration of ‘80s wrestling camp premiered last summer, a welcome shock of hair-sprayed insolence, pink lamé, and feminine power. By the start of season two, GLOW’s cast has developed the sort of intimacy particular to those who are abruptly thrown together and tasked with creating art, all the while wading through one another’s idiosyncrasies and prejudices. By now, they’ve been bundled two by two into The Dusty Spur motel in Van Nuys where, like a gaggle of boarders, they cohabit while working on the show. The job entails intense physical familiarity: While sparring in the ring, the women render themselves absolutely vulnerable, trusting one another to safeguard their bodies. And on a less delicate note, nearly every cast member, at one time or another, rams the face of a coworker into her crotch.

Boundaries fizzle accordingly, yielding a vast spectrum of tender gestures. Afflicted by a stubborn case of constipation, Melrose (Jackie Tohn) entreats roommate Jenny Chen (Ellen Wong) to administer an enema, which she does—in exchange for Melrose’s most prized jacket (frankly, that seems fair). When Ruth must make a trip to the emergency room, her companions cluster in the waiting room, glowering at the suspicious nurses, dosing Ruth with Valium and Klonopin with grandmotherly attention, and swiping blankets and pillows from other patients to ensure their friend every possible comfort (“I think he’s dead anyway,” says Sheila of a nearby patient, all the while plumping stolen pillows behind Ruth’s head).

Because the show is not wholly preoccupied with the wrestlers’ relationships, we aren’t witnesses to the little particulars of each friendship the way we are in Broad City or during the most compelling moments of Orange Is the New Black. The exception is the relationship between Ruth and GLOW’s apple pie American star, Debbie Eagan (Betty Gilpin), alias Liberty Belle. Despite the showrunners’ evident—and crucial—concern with diverse racial and sexual dynamics, these two women remain planted at the narrative center, as the show parses the relics of sororal trust that was broken when Ruth slept with Debbie’s husband. GLOW encircles this tangle, reminding us that neither woman is willing to abandon the other, but illuminating reconciliation as a wretched, and sometimes impossible trudge.

The friendships both Ruth and Debbie engage with the rest of the cast are markedly uneven. They tend to list against the women of color—particularly Carmen Wade (Britney Young), Cherry Bang (Sydelle Noel), and Tammé Dawson (Kia Stevens), whose work in the ring is GLOW’s lifeblood. GLOW is a spectacle of women’s empowerment, but the show makes clear, in this business not all women are empowered equally.

Early in the season, Debbie becomes a GLOW producer after negotiating a contract far more advantageous than the ones given to her cast members, much to the chagrin of director Sam Sylvia (Marc Maron) and Bash Howard (Chris Lowell)—a rich boy who bankrolls the series as a passion project. Accordingly, Sam and Bash try to circumvent her by arranging meetings when Debbie, who has recently become a single mother, must return home to fulfill various maternal duties. She counters by insisting that they meet over dinner at her house in Pasadena—a savvy, domestically cozy plan. Sam later tells Bash he’s ditching, and Bash, ever the puppy, follows suit. “Women,” he scoffs. “It’s like, first they want a room of their own. And then they want a seat at the table. And then they even want us to come and eat at that table, even when that table is way out in Pasadena. And I’m like, ‘what happened to the room?’”

Tammé, who performs as “Welfare Queen” in the ring—and is GLOW’s current defending champion—overhears Bash and Sam as they agree to abandon Debbie. She decides to show up for the dinner instead of them. What follows that evening is a conventional, but delicately executed scene in which two women from vastly disparate backgrounds break bread. When Tammé blithely mentions that she worked on an airline food assembly line for seven years, Debbie’s face twitches—a near-imperceptible gesture, but one naked in meaning. Debbie, the blonde bombshell with a notable soap opera credit on her resumé and a gleaming house in the suburbs—who waltzed onto GLOW’s set smug in her casting as its leading lady (and none too disappointed that her privileged status would rankle with Ruth)—has never considered that some of her castmates, particularly a working class, single mother like Tammé, have not always had the chance to do more genteel work.

Debbie complains to Tammé the tribulations of being outnumbered by Sam and Bash. “It turns out being a producer is … like your plastic crown,” she remarks. “Just because it’s shiny and you fought for it doesn’t make it worth more than a party favor.” Tammé is too gracious to suggest that, perhaps, becoming GLOW’s first champion was significant to her—that she interprets it as an achievement even if Debbie has no need for such paltry validations. To be sure, Debbie is contending with unbridled sexism, but as she laments her plight in the plush setting of her dining room she ignores the material advantages of her position—that her successful, white ex-husband Mark (Rich Sommer) has access to the executives who have empowered Debbie, even if that power seems, to her, illusory.

And of course, even illusions can create real effects. The other wrestlers immediately believe that Debbie wields more influence than them. “Does she get better lighting than us now that she’s a producer?” Jenny wonders aloud, as Liberty Belle bounces on their motel room television set, all perk and sparkle. “No, that’s just the internal glow that comes from power,” Melrose responds, with resigned acidity. Tammé, for her part, comforts Debbie despite the asymmetry of their positions. She would never have considered asking to be promoted as a producer, or so we can assume, for she recognizes the role to which she is circumscribed: the entertainment, a product to be sold by those who grip the reins.

Ruth, meanwhile, frets over her own position within the GLOW hierarchy because Sam is jealous of her director’s eye—and not above punishing her for imagined crimes against his authority. Together with the cast and one of the cameramen, she films a romp of a title sequence, and the network executives are delighted by it. Sam, on the other hand, condemns it as an act of insubordination. Yet he quickly forgives her. Although Sam’s moods and fragile ego are aggravating, they’re little more than fleeting obstacles for Ruth. Ultimately, she has his ear, and he regards her with affection that he doesn’t extend to the rest of the cast.

The showrunners illuminate this disparity between the treatment of Ruth and Debbie compared to the rest of the cast, and they gesture to its racist implications. Towards the season’s end, Sam has a brief exchange with Arthie (Sunita Mani), alias Beirut, whose efforts to recast her narrative—she currently performs as a Middle Eastern terrorist—are thwarted by two of the white cast members. She tells Sam that she failed out of medical school in the midst of working on GLOW. “You didn’t notice I always had books with me?” she asks him, perplexed. “No,” he replies flatly. “But I don’t really pay attention to all of you.” He’s nothing if not honest. Ruth is the only wrestler Sam designates as irreplaceable when in fact Carmen—the only cast member with a wrestling background—could harpoon the show’s success if ever she walked away.

GLOW brandishes the trappings of empowerment, but is at its core combative: One woman vanquishes another in a choreographed battle.Her loyalty to GLOW, and to Ruth and the rest of their teammates, means that she doesn’t. Like Tammé, she knows that her body—brown, unruly, unconventional in its charms—precludes her from demands on Sam’s time. Beloved by her teammates as a fussy, bright-eyed darling, Ruth—who, like Debbie, believes that “it’s never easy” for her—that her life is plagued by false starts and misadventure—basks in the glow of success, all the more luminous for the shadow at her back, where the underdogs of GLOW stand and patiently abide.

At the start of the season, Ruth, in a guileless effort to advocate for her coworkers, appeals to Sam. “We care about each other,” she avows. “We’re a team.” But Sam is determined to puncture Ruth’s dewey-eyed optimism at every turn. “Oh, you’re not really a team,” he sneers. “This isn’t basketball.” He invokes this comparison to underscore each cast member’s replaceability, but in fact, it resonates on an even more sinister register. GLOW brandishes the trappings of empowerment, but is at its core combative: One woman vanquishes another in a choreographed battle designed for a male viewer. Ornaments first, warriors only in fetishized pretense, they are, after all, the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling.

No comments :

Post a Comment