The Supreme Court handed down a major decision on digital privacy on Friday, ruling in Carpenter v. United States that Fourth Amendment protections from “unreasonable searches and seizure” apply to cell-phone location data. In short, police need a warrant to electronically retrace a cell phone owner’s steps in a criminal investigation.

“We decline to grant the state unrestricted access to a wireless carrier’s database of physical location information,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the 5-4 majority, citing the “deeply revealing nature of [cell-site location information], its depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach, and the inescapable and automatic nature of its collection.” Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan joined the opinion.

Friday’s ruling extends what’s become a theme for the Roberts Court: ensuring that Americans’ privacy rights keep pace with technological advances. In the past six years, the justices have also ruled that cops need a judge’s permission to attach GPS tracking devices to suspects’ cars and to search a person’s cell phone during an arrest. Friday’s decision continued the court’s trend.

“By recognizing that we have Fourth Amendment protections in cell phone location information, Carpenter appears to be a sweeping decision in favor of civil liberties and privacy,” Elizabeth Joh, a UC Davis law professor who specializes in the Fourth Amendment and digital privacy, told me. “The majority opinion avoids a mechanical interpretation of the law and instead recognizes the ‘seismic shifts brought about by digital technology.’”

For most of American history, there were practical limits on the government’s ability to systematically invade its citizens’ privacy. Tracking the movements of every person at all times in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would have required feats of manpower and bureaucracy beyond all but the most despotic regimes’ dreams. Modern technology, for all its benefits, has also changed that calculus by making vast quantities of personal information available at a moment’s notice.

“Here the progress of science has afforded law enforcement a powerful new tool to carry out its important responsibilities,” Roberts wrote, referencing an earlier court ruling. “At the same time, this tool risks government encroachment of the sort the Framers, ‘after consulting the lessons of history,’ drafted the Fourth Amendment to prevent.”

Friday’s ruling is also good news for Timothy Carpenter, the case’s titular namesake. He was one of four men convicted by a federal jury in 2011 for participating in a series of robberies targeting electronic stores in Michigan and Ohio. To prove that Carpenter was at the scenes of the crimes, federal investigators sought what’s known as historical cell-site location information (CSLI), from Carpenter’s cell phone.

What is historical CSLI? As part of their everyday functions, cell phones regularly transmit data to nearby cell towers, like submarines using sonar to navigate the ocean depths. In denser urban areas, a cell phone will ping multiple towers at the same time, making it possible to triangulate the source with increasing precision. Each cell tower records those pings and who sent them, storing the information in databases maintained by each telecommunications company.

With enough data from enough towers, anyone with access to the database could stitch together a comprehensive account of when and where each cell phone has been. At least 95 percent of Americans have personal cell phones, many of whom rarely step away more than a few feet from them. As a result, tracing where a cell phone has been is no different to tracking where a person has been. The privacy implications are inescapable.

“Whoever the suspect turns out to be, he has effectively been tailed every moment of every day for five years, and the police may—in the Government’s view—call upon the results of that surveillance without regard to the constraints of the Fourth Amendment,” Roberts wrote. “Only the few without cell phones could escape this tireless and absolute surveillance.”

Instead of seeking a search warrant to obtain Carpenter’s data, federal investigators used a provision in the federal Stored Communications Act to obtain what’s known as a 2703(d) order. The distinction is a crucial one. A warrant requires investigators to show they have “probable cause” to believe the search will uncover evidence of a crime, while 2703(d) orders have a lower threshold under federal law: Police need only offer “specific and articulable facts” that the records sought will be “relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.”

Investigators ultimately obtained 127 days of cell-site records from two different mobile providers, which yielded 12,898 location points that revealed Carpenter’s movements. A federal agent testified that those points placed him near four of the robbery locations during the robberies in question. A jury found him guilty on multiple robbery and firearm-related charges and sentenced him to more than 100 years behind bars.

Carpenter asked lower courts to throw out the evidence on Fourth Amendment grounds. But they declined, citing two Supreme Court precedents dating back almost four decades. In the 1976 case United States v. Miller, the court upheld a whiskey bootlegger’s conviction after prosecutors obtained his bank records without a warrant. Three years later in Smith v. Maryland, the court signed off on the warrantless use of a pen register, a device that recorded which phone numbers were dialed on a particular telephone line.

Taken together, Miller and Smith established what’s known as the third-party doctrine. The Supreme Court often uses a “reasonable expectation of privacy” test to determine whether a police method counts as a Fourth Amendment “search,” and therefore whether a warrant is needed. Under the third-party doctrine, Americans lose a reasonable expectation of privacy if their personal information is stored by a third party, as with the bank records in Miller, or made readily available to a third party, as with Smith and the telephone company.

Applying that doctrine to modern technology, which is far more pervasive and ubiquitous than it was when Smith and Miller were decided in the 1970s, is an uneasy proposition. In 2012, the justices ruled in United States v. Jones that federal agents had violated the Fourth Amendment when they attached a GPS device to a car without a warrant. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a concurring opinion in which she called on the court to revisit the third-party doctrine in light of technological advances.

“This approach is ill suited to the digital age, in which people reveal a great deal of information about themselves to third parties in the course of carrying out mundane tasks,” she wrote. “People disclose the phone numbers that they dial or text to their cellular providers; the URLs that they visit and the e-mail addresses with which they correspond to their Internet service providers; and the books, groceries, and medications they purchase to online retailers.”

Monday’s ruling in Carpenter began to move the court in that direction. It explicitly carves out an exception of sorts from the third-party doctrine for historical CSLI, citing its unusually intrusive nature. “After all, when Smith was decided in 1979, few could have imagined a society in which a phone goes wherever its owner goes, conveying to the wireless carrier not just dialed digits, but a detailed and comprehensive record of the person’s movements,” Roberts wrote.

Roberts explicitly stressed that the court’s ruling was narrow, but the underlying logic seems hard to contain. “Carpenter suggests that the third-party doctrine is less of the bright-line rule that the cases suggest and more of a fact-specific standard,” Orin Kerr, a University of Southern California law professor who specializes in computer law, wrote for Reason. “At the very least, that is going to invite a boatload of litigation on how far this new reasoning goes.”

This isn’t the first time the court has bent past rulings to meet the challenges of the digital age. In Jones, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a majority opinion in which he found warrantless GPS tracking unconstitutional by citing Entick v. Carrington, a 1765 English court case on trespassing. Justice Samuel Alito scoffed that the court “has chosen to decide this case based on 18th-century tort law.” Scalia was unamused. “That is a distortion,” he wrote. “What we apply is an 18th-century guarantee against unreasonable searches, which we believe must provide at a minimum the degree of protection it afforded when it was adopted.”

In 2014, the justices again took technological changes into account in Riley v. California. Generally speaking, the courts have found that the Fourth Amendment doesn’t stop police from searching suspects during an arrest, citing the need to secure evidence and ensure officer safety. But the court drew a line when it came to searching a suspect’s cell phone under that exception. The immense amounts of personal data on a phone placed it beyond the exception’s scope. “The fact that technology now allows an individual to carry such information in his hand does not make the information any less worthy of the protection for which the Founders fought,” Roberts wrote for a unanimous court.

Previous generations of Supreme Court justices were often too willing to bend the Fourth Amendment when new technologies made it possible. In the 1928 case Olmstead v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that wiretapping didn’t require a warrant at a time when telephone technology was still relatively new. It took 39 years for the court to reverse course. Roberts and his colleagues have made clear that they’re not eager to make the same mistakes again.

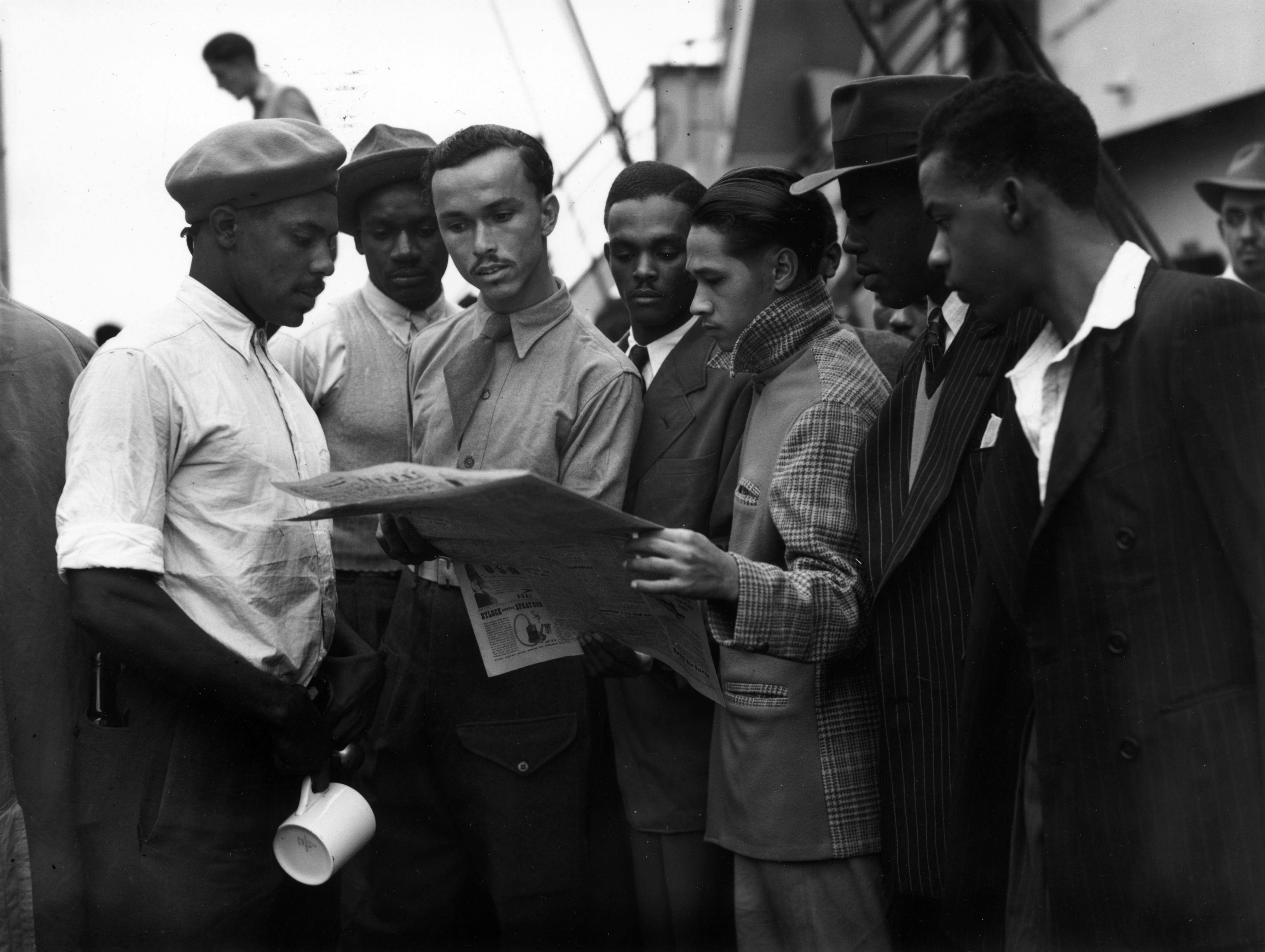

Seventy years ago today—June 22, 1948—a passenger ship carrying 492 Jamaican immigrants arrived in Essex, London. The Empire Windrush was the first of many ships to come, as the British government recruited migrants from the Caribbean Commonwealth to help rebuild the economy after World War II. These arrivals came to be known as the Windrush generation. “It is unclear how many people belong to the Windrush generation, since many of those who arrived as children travelled on parents’ passports and never applied for travel documents—but they are thought to be in their thousands,” according to the BBC.

These immigrants, now elderly, are legal UK residents. But since last year over 5,000 of them found themselves homeless, unemployed, denied health care, or deported altogether as a result of Theresa May’s “hostile environment” policy, which requires employers, landlords, banks and the National Health Service to conduct visa inspections. In April, high commissioners from all of the Caribbean Commonwealth nations rebuked the UK government over the scandal, the British home secretary resigned, and the Home Office assembled a Windrush task force. In a more symbolic gesture, the government designated today, June 22, as “Windrush Day.”

The New Republic spoke to Trevor Phillips, the former head of the British Commission for Equalities and Human Rights and co-author of 1999’s Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multiracial Britain, about the past, present, and future of the Windrush generation—of which he is a descendant.

How were the Windrush immigrants greeted in the UK?

Bear in mind that, at that time, the word “immigration” didn’t have quite the same meaning, or didn’t carry the same weight. All of these people carried British passports because they were members of the British empire. There was no distinction between a British person born in Bombay, or Georgetown, or Leeds. They had exactly the same thing, and that was how people thought of it. Secondly, there were no immigration formalities. If you look at the pictures of people coming down the gangway and walking onto the dock, there are no immigration officials there demanding passports. So the status was quite different, and the numbers involved were tiny. Right through the 1950s, total immigration would’ve been measured in four figures—about 2,450 people a year.

So that’s context, and that then tells you something about why there was a sort of schizophrenic response. When it became known that a boat that was bringing these 500 or so people, the colonial office panicked and thought it was quite a large number, because the annual immigration numbers would’ve been three or four thousand. There was a lot of discussion about how they would fit in, where they would live, whether there’d be jobs for them. They even sent a warship to shadow Windrush as it came into the English Channel. There was an official anxiety not so much about immigration, but about integration. On the other hand, when the guys got here, there wasn’t too much anxiety in the street. There were welcome parties, and all that sort of thing.

Towards the end of the 1950s and ’60s, things became a bit different, partly because Britain was in transition from the war. People had put up with all sorts of things—rationing and so on—in the late ’40s and early ’50s because of the deprivations of war, but by the end of the 1950s, they were expecting a bit more. There were conflicts over housing—particularly in cities like London and Nottingham—and at first, what you might call full-fledged race riots happened in Northwest London, like in Notting Hill in 1968.

That was dressed up as a conflict between young men with not enough to do and teddy boys and so on, but it was really about housing—who’s got homes and who couldn’t get homes. There was a lot of resentment about the fact that some of the Windrush generation had come to Britain, couldn’t get municipal housing, and weren’t put into public housing, so they saved up and managed to get themselves rented housing. Some started to buy housing.

Why did this general attitude change over time?

War ended in 1945. By 1957-58, the population was expecting a bit better, and they were rather cross that things weren’t moving faster. So the immigrants received a bit of the backlash from that. And the other thing that’s made quite a big difference—and this is a generational point—is that the first group that came from 1948 to 1950 were mainly men. They were mainly male, but women followed. And so what then followed? Children. A lot of people, of whom I’m one—and I’m probably one of the early ones of Caribbean heritage, who were born in the mid-1950s and late-1960s—by the early 1960s, these children turned up in schools.

When they started seeing these people at the school gates, they realized that these people they thought were just coming for a while, because they couldn’t get jobs back home. Like my parents, they thought they’d come, make a bit of money, save up, go home, build a house, and become, by colonial standards, middle-class. Well, what happens when people like me start turning up at schools is that people start realizing rather quickly, that isn’t going to happen. Nobody’s going home.

It’s at that point I think that sentiment starts to change because you then have to address a different population. You then have to worry about things like discrimination, which not too many were worried about, because people who weren’t liberal couldn’t care less and people who were liberal didn’t like it but thought, “Oh, well, it’s not going to be an issue for very long because they won’t be here for very long.” And then everybody realizes it’s going to be a permanent question. So that’s why you get, in 1955, the first anti-discrimination law.

Some of the Windrush generation’s immigration records have been destroyed by the government. How can they attain citizenship without them?

The government is going to have to work a bit harder here. They’re going to have to do some investigation. Almost all of these people will probably belong to one or two churches; most of them will have belonged to the same church for their whole life. I was christened in a church about 20 minutes from where I live now; if and when I keel over, I’m going to be buried in that church. So somewhere in the church records, there will be my christening, my Sunday school attendance, all of that.

My idea is that what they can do instead of putting the whole burden on the person concerned to dig out all kinds of official documents that have probably been shredded and not digitally recorded, is to allow some latitude to present some kind of records—or to get a letter from your minister. Some of the women will have records pertaining to their hospitalization from giving birth.

I think the government would make it less difficult if they, first of all, said that there’s a presumption of innocence. Right now, there’s a presumption of guilt: Unless you can produce all these documents, you must be illegal. Well, I think they ought to just simply reverse that, and state a presumption of innocence, unless someone can demonstrate that you weren’t where you say you are. And secondly, if there is some doubt, then the government ought to agree to allow a wide array of documentation than the Home Office currently allows. They’re definitely thinking along those lines.

Do you think the rise in anti-immigrant sentiment is anomalous, or the beginning of a broader cultural shift?

Public opinion has really come down very firmly on the side of the Windrush migrants. That is the thing that would be most striking. Most people in this country—whether they’re in government or not, whether they’re right or left—would always have assumed that British people, at best, didn’t care very much about what happened to a bunch of old black people and, at worst, would’ve assumed that they would be hostile to anybody who appeared to be breaking immigration laws. That’s the thing that’s most surprising: the wave of public indignation about the treatment of these people.

So I don’t really buy the idea that the Windrush scandal demonstrates that there’s a growing anti-immigration sentiment; I’d go as far to say the opposite, in fact. If you look everywhere else in Europe, exactly the opposite of what happened here is taking place. In Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Italy, there would never have been this wave of public support for immigrants who’ve been treated in this way.

I think the anomaly here is that Britain is in a completely different mood to the rest of Europe. To be frank, people who tell you that there’s this great wave of anti-immigrant sentiment here are saying that because that’s what they would like to believe, and they want to be the people who save black folks, and fight for all rights and all of that. This country isn’t like that at all—that’s why you’ve heard of this scandal.

If you were to update your book with a new chapter, what would it say?

Ah! Very interesting question. I have a very particular answer to that, which might take quite a bit of explaining to an American audience, but let me put it this way: The most interesting thing about the Windrush story right now is that although the scandal is current, it isn’t the most important thing that has happened. The most important thing is about to happen. Somewhere in the next decade or 15 years, something is going to happen in Britain that isn’t happening anywhere else in Europe, and hasn’t happened anywhere in the Americas.

If you refer to a person of Caribbean origin in Britain right now, you tend to be talking about somebody who’s got two black parents, two Caribbean parents, like me. Both of my parents are from British Guiana. Somewhere between now and 2030, the majority of people of Caribbean origin will either have a white parent or a white grandparent. That’s quite a substantial thing; it’s the fastest growing demographic group in the UK. And I think it is, as a phenomenon, unprecedented. There are lots of people who have mixed heritage in South Africa and the United States and Brazil, but for the most part, that is the result of slavery and oppression and rape. It is very unusual to have a group this size of mixed people of dual heritage, which is the result of free choice.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Melania Trump flew to Texas on Thursday to meet migrant children who had been separated from their parents, and perhaps also to save face for the White House—to show that her husband, who ultimately is responsible for the children’s separation, does care about their fate. “I’d also like to ask you how I can help these children to reunite with their families as quickly as possible,” she told staff at the Upbring New Hope Children’s Center. To the kids themselves, she said, “Good luck.”

Later, though, The Daily Mail revealed that while boarding her flight to Texas, Trump had worn a military-style jacket with the words “I Don’t Care, Do U?” printed on the back. What did she mean by the jacket? “It’s a jacket,” her spokeswoman told reporters. “There was no hidden message.” President Donald Trump insisted there was one, tweeting that it “refers to the Fake News Media. Melania has learned how dishonest they are, and she truly no longer cares!”

Which is to say, if the Texas trip was meant to humanize the Trumps and the administration’s policies, it failed. The first lady turned a humanitarian visit into a spectacle about herself, and in doing so, she put the lie to the purpose of her trip.

Trump’s immigration policy remains as ugly as ever, despite his latest efforts to prove otherwise. On Wednesday, he signed an executive order that ends family separation at the border, and on Thursday a Customs and Border Patrol official told The Washington Post that the government would cease its “zero-tolerance policy” of prosecuting all adult migrants who are caught after crossing the border illegally, and instead would only prosecute adults without children. But a Department of Justice official immediately disputed the CBP official’s claim, saying “zero tolerance policy is still in effect.” And later on Thursday, a Pentagon official said that 20,000 migrant children will be housed on military bases starting as early as July.

Amid this chaos and confusion, it’s nonetheless clear that while families might not be separated anymore, they will be detained together indefinitely. (It takes hundreds of days to adjudicate immigration cases.) It’s also clear there’s no government plan in place to reunite the 2,300 children separated from their parents under the zero-tolerance policy since early May. (For some children, it may come down to whether they managed to remember a phone number.) For all of Trump’s efforts to quell the outrage this week, the inhumanity of his restrictionist immigration policy remains very much intact.

Migration across the southern border has risen for four straight months. There could be as many as 30,000 migrant children in government custody by August, according to an administration official. There will be more camps—“tent cities”—on military bases and elsewhere, and many will be occupied by children who either crossed the border alone or who were separated from their parents by CBP. If indeed the administration is no longer prosecuting migrant adults who came with children, then they will need camps or other detention facilities for families, too. (The Pentagon said the military bases will house unaccompanied children, but it’s unclear where parents with families will be kept.)

What dangers will these children be exposed to over the many months they’re destined to live in these places? On Thursday, the Associated Press reported that immigrant minors jailed in a juvenile detention facility near Staunton, Virginia, filed a lawsuit alleging persistent abuse from guards. The article’s description of the allegations recalls Abu Ghraib: “Multiple detainees say the guards stripped them of their clothes and strapped them to chairs with bags placed over their heads.” The abuses reportedly began under the Obama administration, but some teenagers had been put into the facility because Trump’s CBP believed they were members of MS-13, an assertion that both the teens and the facility’s staff dispute.

In other facilities, children have begun to harm themselves. Some have attempted suicide. Children incarcerated in the Shiloh Treatment Center in Texas say they have been forcibly injected with strong psychotropic drugs. A lawsuit filed on behalf of the children charges that the Office of Refugee Resettlement uses the drugs as “chemical strait jackets.” If the camps become semi-permanent fixtures, as seems likely, it’s possible to think of them as refugee camps: institutions forced on people who cannot return home without facing violence and who have been forbidden from going nearly anywhere else. The camps are certain to traumatize many migrants.

What comes next for these migrants, and for America’s immigration policy overall? It’s likely that not even Trump knows.

He has little room to maneuver politically. His administration had insisted for weeks that it wasn’t separating families at the border, and then it was proven otherwise. It’s difficult to deny family separation when audio of screaming migrant children goes viral. But Trump entered the Republican primary with the cogent political goal of immigration restriction, and his actions as president prove he feels particularly bound to the promises he made—a border wall, a Muslim ban, mass deportations.

Politico reported on Monday that Stephen Miller, a senior White House policy adviser, and other top aides “are planning additional crackdowns on immigration before the November midterms, despite a growing backlash over the administration’s move to separate migrant children from parents at the border…. The goal for Miller and his team is to arm Trump with enough data and statistics by early September to show voters that he fulfilled his immigration promises—even without a border wall or any other congressional measure, said one Republican close to the White House.”

That effort might seem imperiled after Trump’s retreat later in the week, amid growing criticism of Miller from Republicans. But Miller believes the zero-tolerance policy makes good political sense for Trump, in that it energizes his base. He might be right: A majority of Republican voters supported the family separation policy. Trump is loyal to these voters, and them alone. It explains why, this week’s executive order notwithstanding, he hasn’t budged one bit on his broader immigration stance.

“We shouldn’t be hiring immigration judges by the thousands, as our ridiculous immigration laws demand,” he tweeted on Thursday. “We should be changing our laws, building the Wall, hire border agents and Ice and not let people come into our country based on the legal phrase they are told to say as their password.” On Friday morning, he was at it again: “We must maintain a Strong Southern Border. We cannot allow our Country to be overrun by illegal immigrants as the Democrats tell their phony stories of sadness and grief, hoping it will help them in the elections.”

Note the word “phony.” Trump does not believe his immigration policies have caused any sadness or grief—at least not to innocent people. He believes, sincerely, that immigrants are dangerous, that even their children are threats, and so the means justify his nativist ends. Grief is the point, which is why he will cause unimaginable misery for the migrants who are already here and for those who are still to come.

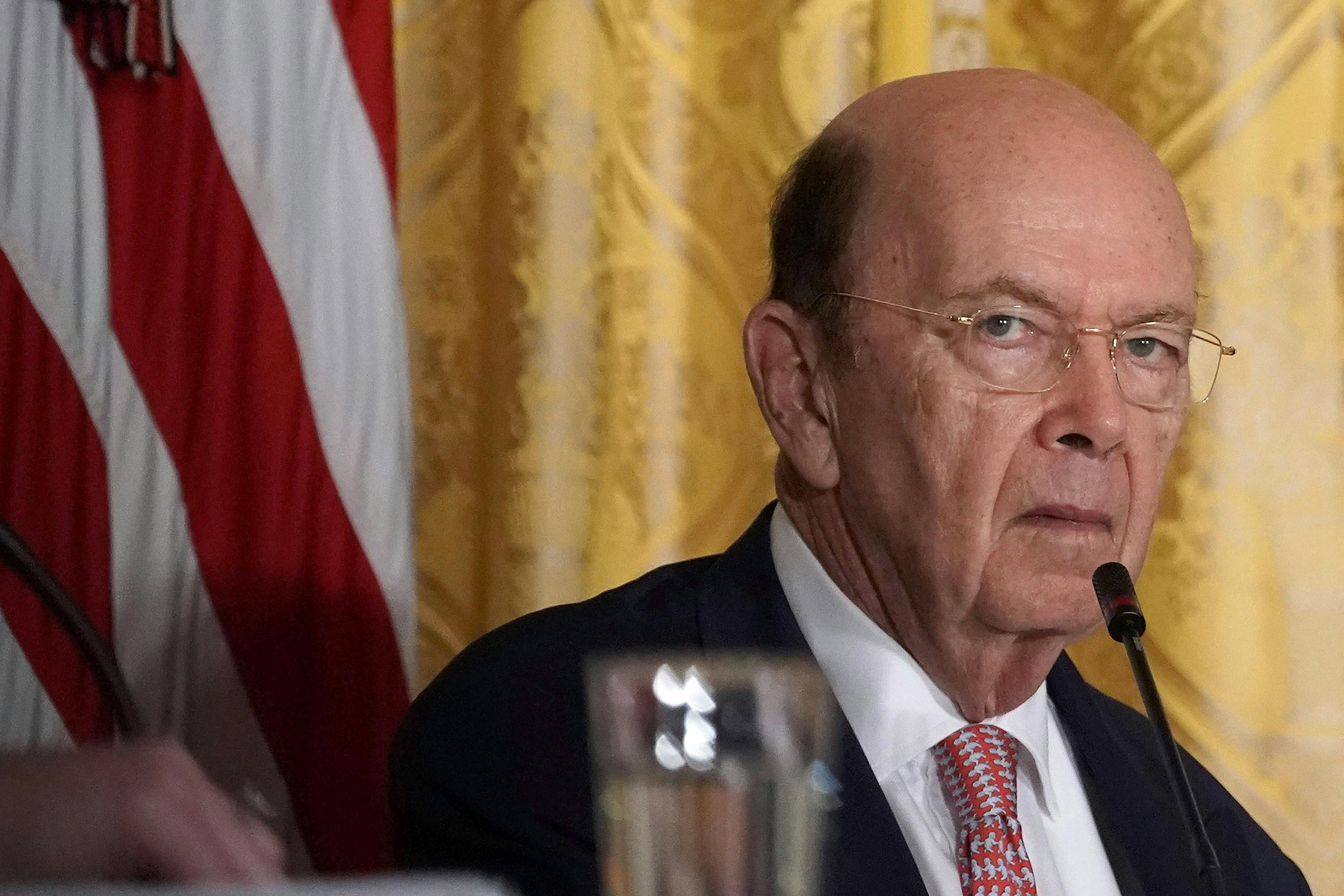

Days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, the Office of Government Ethics released an agreement with Wilbur Ross, then the nominee to head the Commerce Department, in which the octogenarian tycoon agreed to divest from a significant number of his holdings and step down from the boards of over 20 companies in which he held financial interests. Though Ross’s divestment should be considered the bare minimum for cabinet members, it nevertheless stood in contrast to the incoming president’s refusal to divest from his companies and persistent financial obfuscation. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat, told him, “You have really made a very personal sacrifice. Your service has resulted in your divesting yourself of literally hundreds of millions of dollars.”

But Ross made no such sacrifice. Earlier this week, Forbes reported that Ross had maintained multiple investments that constituted significant conflicts of interest, including ownership stakes in several Chinese-owned enterprises, a Cyprian bank being investigated by special counsel Robert Mueller, an auto parts company affected by Trump’s changes to trade policy (which Ross, as secretary of Commerce, is overseeing), and a shipping company with substantial ties to Russian oligarchs (who are close to Russian President Vladimir Putin).

The assets that Ross has formally divested, moreover, are being managed by a trust—meaning that Ross did not really divest from them at all, since he still knows which assets will return to his control when he leaves government service. Adding insult to injury, Ross even attempted to profit off his disclosures, shorting stock in the shipping company after being informed that his holdings were about to be made public last fall.

These revelations have resulted in something less than a media firestorm, thanks in large part to the outcry surrounding the Trump administration’s policy of separating migrant families at the border. But Ross’s brazen corruption is also part of a larger story. From EPA chief Scott Pruitt’s use of his office for personal gain—to say nothing of his purchasing expensive lotions and “tactical pants”—to the president’s own murky financial assets and connections, corruption is as much the story of the Trump administration as its cruelty toward minorities.

Ross’s ties to Russian oligarchs were first made public last fall, when the Paradise Papers revealed that he owned a stake, via a “chain of offshore investments,” in Navigator Holdings, a shipping company with deep connections to Putin’s inner circle, including some under U.S. sanctions. “I don’t understand why anybody would decide to maintain this kind of relationship going into a senior government position,” Daniel Fried, who served as secretary of state under George W. Bush, told The Guardian. “What is he thinking?” Ross’s press secretary, meanwhile, dismissed the connection, claiming that Ross “recuses himself from any matters focused on transoceanic shipping vessels.”

But it was Ross’s response to the revelation of his holdings, as revealed by Forbes, that is most shocking. Ross placed a short on Navigator’s stock days before his connection became public—meaning he was betting it would fall in value—a move that essentially means he was doubling down on corruption. Whether it was lawful or not is a subject of debate, though it could fall under the category of “insider trading.” But it is certainly unethical behavior for a public servant, particularly a cabinet member.

Ross said that his divestment from Navigator Holdings was pre-planned, making the timing coincidental. That may very well be true, but Ross’s denial contained more than a little hair-splitting. “Insider trading requires action be taken based on non-public information about a particular company,” Ross told CNN. “The reporter contacted me to write about my personal financial holdings and not about Navigator Holdings or its prospects. I did not receive any non-public information due to my government position, nor did I receive any non-public information from a government employee. Securities laws presume that information known to or provided by a news organization is by definition public information. The fact that the reporter planned to do a story on me certainly is not market moving information.”

Ross is arguing that because a news organization knew about his holdings, even though it had not made that information public, this could not be insider trading. It was, in essence, already public information. Whether that will hold up in a court of law remains to be seen.

Then there’s the Luxembourg-based International Automotive Components Group (IAC), which Ross created by merging a number of auto parts companies in 2006. In the fall of last year IAC closed a joint venture with a Chinese state-owned company. “As part of the deal,” Forbes reports, Ross’s company “took a 30 percent interest alongside a state-owned company named Shanghai Shenda and got roughly $300 million in cash.” This is a problem because Ross is currently investigating, at President Trump’s behest, whether or not the United States should tax imports on foreign cars. Ross’s findings could very well be informed by his family’s holdings in IAC, which will ultimately undermine whatever Ross recommends.

While Republicans in Congress have largely looked away from corruption within the Trump administration, Ross is perhaps uniquely vulnerable here, given the general lack of appetite for a trade war with China in Congress. So far, congressional Republicans have been unable to sway the president from protectionism, but Ross’s holdings have given them an opening.

The opening is even larger for Democrats, for whom corruption remains a potent message heading into the midterms (and 2020). Ross’s self-dealing and conflicts of interest should be part of a larger mosaic, encompassing Trump’s blatant use of the presidency for economic gain. The Russia connection, when it comes to Ross, is also tantalizing, but the larger point is this: Ross, like so many in the administration, is compromised not by connection to a foreign power, but by his own financial interest.

It’s invisible primary season—the time when candidates begin launching book tours, jockeying for endorsements, and locking down political strategists—and the mayors of some of America’s most liberal cities have begun making pilgrimages to Iowa. In April, Los Angeles’s Eric Garcetti traveled around Des Moines for two days, shaking hands with Democratic activists at a dive bar, rubbing shoulders with firefighters and union members, and attending an LGBTQ gala. “I think people probably imagine, as I’ve said before, that we’re mostly a city full of Kardashians and reality stars,” Garcetti joked of Los Angeles. “We’re actually everyday folks who are nurses and bus drivers and factory workers and firefighters.” Casting himself as an all-American boy (or rather a “Mexican-American-Jewish-Italian” boy, his preferred term) from “middle America” (he grew up in Brentwood), Garcetti was clearly auditioning for a 2020 presidential run, although he wisely didn’t quite say it. “I’m not here looking for a new job for me,” he told reporters. “I’m looking for more new jobs for Americans.” This was met with some skepticism: Two previous stops on his tour, New Hampshire and South Carolina, just happen to host primaries right after the Iowa caucuses.

Garcetti isn’t the only Democratic mayor with presidential ambitions. Five months earlier, New York’s Bill de Blasio arrived in Iowa, hoping to position himself as a sort of second coming of Bernie Sanders. Hailing a “new Progressive era,” de Blasio declared a speech in Des Moines the new speech at Goldman Sachs. “We are not the party of elites,” he said. “We are the party of working people.” A political action committee controlled by South Bend, Indiana’s mayor, Pete Buttigieg—the Rhodes scholar, veteran, and Harvard grad whom New York Times columnist Frank Bruni has said could be the “first openly gay president”—has been spending money in Iowa (as well as Georgia, Arizona, Michigan, and Colorado) since March. Mitch Landrieu, who just finished his second term as mayor of New Orleans, hasn’t been to Iowa yet, but he did just release a memoir, In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History—a reference to the well-received speech he gave last year calling for the removal of Confederate statues in New Orleans. Julián Castro, who served as mayor of San Antonio before joining the Obama administration in 2014, has also visited New Hampshire twice in the past three months. The message is clear: With no obvious front-runner heading into the 2020 primary, charismatic, well-connected Democratic mayors think they could make the leap from City Hall to the White House.

That’s not to say that any of these mayors will actually win the presidency—most people who run for president lose. But if anything has become clear since the last presidential contest, it’s that the rules governing American politics no longer hold. “Every campaign is a new campaign, and everyone makes the mistake of running the last one,” Garcetti said in Iowa. “No African American could ever become president until one was; no reality star could be president until one is.” The Democratic Party is more diverse and represents more educated voters than ever, and cities have become the centers of the fight against the Trump administration. If the future of the party, as some have argued, looks, at least demographically, like Los Angeles and New York, then why shouldn’t the mayor of one of those cities become the party’s nominee?

History hasn’t been kind to mayors with presidential ambitions. Of the three who have reached the White House—Andrew Johnson, mayor of tiny Greeneville, Tennessee; Grover Cleveland of Buffalo, New York; and Calvin Coolidge, who led the college town of Northampton, Massachusetts—none was mayor for more than three years, and all served as governor afterward. Two of the three (Johnson and Coolidge) became president only after the death of their predecessor. And only Cleveland is considered a successful chief executive by historians. The last time a sitting mayor received his party’s nomination for president was 1812, when DeWitt Clinton, the mayor of New York City, ran as a Federalist and narrowly lost to James Madison.

Until very recently, America’s most powerful mayors wouldn’t have considered running for the presidency. New York’s Jimmy Walker and Chicago’s Richard J. Daley and “Big Bill” Thompson all had the resources to mount a national campaign; they might even have had the national profile. But their cities were dominated by political machines greased by graft and corruption—and their years of dealmaking left them with too many easily discovered skeletons for a national campaign. (Thompson is the exception that proves the rule. He did make a run at the presidency in 1928, funding his “America First” campaign with $3 kickbacks from city drivers and inspectors, but withdrew from the race after winning zero delegates.) Meanwhile, smaller town mayors were seen as too inexperienced for the responsibilities of the presidency—this, combined with limited opportunities to expand their national profiles, ensured none attempted it. What’s more, as America’s culture wars increasingly captured the national debate, people saw cities as centers of vice and crime instead of breeding grounds for leadership.

Of course, that hasn’t stopped mayors from running. Sam Yorty, the Democratic mayor of Los Angeles, ran in 1972, promising, among other things, to use nuclear weapons in Vietnam. Rudy Giuliani, an early front-runner in 2008, ran on his tenure as mayor of New York City during September 11—something that became a punchline as the campaign progressed. Both efforts were short-lived. (Giuliani suspended his campaign before Super Tuesday.) Instead, it has been governors, not mayors, who are able to bridge America’s historic urban-rural divide. They have controlled the executive branch in recent history.

More recently, though, the United States has changed in ways that make it easier for mayors to compete nationally. Mass communication—television and, especially, internet access—has eroded some regional distinctions, and Democrats have seen the country move toward them on many social issues. In 2008, only 39 percent of Americans were in favor of gay marriage; that number is now over 60 percent. More Americans support gun control today, after the Las Vegas and Parkland shootings, than they have in the six years since Sandy Hook.

Mayors not only oversee affluent, booming cities; they’re also a crucial line of defense against the Trump administration’s draconian policies.Demographic shifts have also transformed cities. As former mayor of Washington, D.C., Anthony Williams wrote in City Lab earlier this year, “The demographic line that used to divide city and suburb is blurring. Cities are becoming more white and many suburbs have diversified.” Mayors now not only oversee affluent, booming cities, which allows them to make the argument that they have the experience to be stewards of the national economy; they’re also a crucial line of defense against the Trump administration’s draconian policies on abortion, immigration, and guns. While it might once have been true that cities cared only for their narrow interests, it is now clear that they have become policy laboratories, places where state and national dysfunction can be counteracted.

Democratic mayors have two additional assets as candidates. First, they won’t really have to answer for what they have or have not done to stand up against the president. Some may have to dodge awkward questions about their cooperation with ICE’s deportation efforts or the way their policies increased gentrification or led to the housing crisis. But they won’t be attacked for things like voting to confirm Donald Trump’s Cabinet nominees, supporting his budget, or helping him destroy Obamacare. “I think it’s going to be very hard to get [to the White House] if you’ve been in Washington too long,” Democratic strategist Joe Trippi said. Second, their relative position is strengthened by the Democratic Party’s lack of statewide leaders. Today, after eight years of the Obama administration, there are only a handful of Democratic governors. Some are either too old (California’s Jerry Brown is 80) or too compromised (New York’s Andrew Cuomo is fighting off a corruption investigation, and former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick has been working at Bain Capital since he left office in 2015) to mount a serious presidential challenge. Many of the rest are too inexperienced or just uninterested in the White House.

Still, of the mayors who are likely contenders, only Garcetti seems to have a fighting chance, and even he will have a difficult path: Checking the “Mexican-American-Jewish-Italian” boxes plays a lot better in Beverly Hills than in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. But with a Democratic Party that’s becoming more diverse, educated, and urban, that may not matter as much as it once did: The cities, in some ways, now more closely resemble the mythical “real America” than do small towns.

“Donald Trump proved that you can come from just about anywhere and have a shot at winning the presidency,” Trippi told me. That idea has resonated with more than just conservatives—it has unleashed a wave of political energy that is reordering the way elections are won and maybe even who wins them. “There are a lot of people who think their cities are the new vibrant idea factories, where mayors have to deal with problems and actually solve them—unlike in Washington.”

It’s been quite a week for AT&T. One of the largest providers of wireless, internet, and cable TV in America, it closed an $85.4 billion deal last Thursday to acquire Time Warner, one of the biggest entertainment companies in the world, after a federal court blessed the merger over the Justice Department’s objections. Judge Richard Leon, of the U.S. District Court for D.C., had rejected the government’s argument that AT&T would lessen competition by leveraging Time Warner’s “must-have” television content to drive rival customers to its products.

Within one week, AT&T announced a plan to use Time Warner’s television content to drive rival customers to its products. It’s just one of several announcements from the new conglomerate that show the government was right: AT&T is determined to use its economic and political power to expand its reach and dominate markets.

On Thursday, AT&T unveiled a service called WatchTV, a “skinny bundle” of 31 television channels, many of them under AT&T’s control after the Time Warner merger, as well as on-demand content from those channels. Subscribers to AT&T’s two new unlimited data plans get WatchTV for free, and the pricier plan includes HBO, the crown jewel of the Time Warner merger. Non-AT&T customers who want WatchTV can get it for $15 per month—but without access to John Oliver and Silicon Valley, which would cost another $15 through HBO Now.

AT&T considers this an expansion of consumer choice, a new option for cord-cutters seeking cheap streaming TV. But in reality, AT&T is using its exclusive access to HBO and other Time Warner programming to push people to sign up for its phone plans. It’s no coincidence that AT&T also quietly announced price increases for the unlimited data plans it’s trying to attract people to.

In antitrust parlance, this is known as “tying.” As the U.S. Federal Trade Commission notes, “The law on tying is changing. Although the Supreme Court has treated some tie-ins as per se illegal in the past, lower courts have started to apply the more flexible ‘rule of reason’ to assess the competitive effects of tied sales.” But using HBO to drive cell phone subscriptions, when rivals can’t do the same, should face legal scrutiny. There’s a more subtle form of tying here as well: Any subscriber to AT&T’s unlimited data plans gets a $15/month credit to DIRECTV, AT&T’s satellite TV subsidiary.

Somehow, in the six-week trial over the proposed merger, the idea that AT&T could leverage Time Warner content for cell phone subscriptions never came up. The government’s case focused entirely on television distribution.

AT&T says it can offer 31 streaming channels for $15/month because it will be “ad-supported.” The company will use information about consumers’ personal watching habits to target ads, which it can do because Congress repealed a regulation last year that would have required user consent for such targeting. But AT&T still needs a way to deliver ads for wireless customers, something to rival Google and Facebook’s. Last Friday, CEO Randall Stephenson said he’ll get there by buying companies. “We’re standing up a significant advertising platform; you should expect some smaller, not like Time Warner, but smaller [mergers and acquisitions] in the coming weeks to demonstrate our commitment to that,” Stephenson told CNBC.

Growth through acquisition is how Google and Facebook became so dominant in their respective markets. Facebook has a tool called Onavo that identifies the user bases of rival social networks so it can buy them up if they start to take off. Google bought its ad network by acquiring Doubleclick, AdMob, and other firms. Only a company as deep-pocketed as AT&T could hope to make such a play. The gradual disappearance of startup companies in America goes hand-in-hand with increased buyouts from these big incumbents.

With economic power comes political power, and AT&T flexed those muscles this week, too.

After the Federal Communications Commission’s repeal of Obama-era net neutrality order last year, it was left to the states to ensure that telecoms don’t throttle certain websites. But companies that control the pipes don’t want to lose that opportunity, so they’ve been lobbying against such regulatory efforts on the state level.

A California State Assembly committee on Wednesday gutted legislation that would have set the nation’s gold-standard for net neutrality. The bill was amended to allow “zero rating,” which lets telecoms exempt certain services from counting toward a customer’s data plan. This is perfect for AT&T, which just got a bunch of bandwidth-heavy Time Warner programs to offer to customers. It can exempt those videos from data caps, while charging rivals for the same access. AT&T already does zero rating for streaming DirecTV online. Prioritizing one’s own content above rivals is the very definition of anti-competitive behavior.

The bill’s author, Senator Scott Wiener, withdrew the bill from consideration, saying it was “mutilated” by the Assembly committee. AT&T may have played a role in that. The company recently gave the committee chair, Miguel Santiago, $4,400 toward his re-election, and the eight members of the committee received $230,600 from AT&T over their careers, according to CalMatters’ Dan Morain. Last year, AT&T gave $511,000 to the California Democratic Party, which fundraises with an annual golf tournament at the Pebble Beach course that’s “presented by AT&T.”

In other words, AT&T has used Time Warner programming to bolster its wireless business, openly stated it would concentrate the ad-tech market so it can profit from data collection, and forced into submission the main legislative threat to its business model—all within its first week since the merger.

Why were none of these possibilities considered in the antitrust case brought against AT&T? Why did the government focus so much on whether consumers might pay a little more or a little less for cable TV? Because the judiciary promotes a backwards interpretation of mergers that says the only thing to judge whether they are beneficial or not is “consumer welfare,” which has come to mean whether they offer lower prices. Seven days of the new AT&T’s existence proves the inadequacy of that.

Consumers are harmed when they have narrow options for the type of wireless and TV service they want. They’re harmed when they can’t access certain websites or videos from their Internet service provider. They’re harmed when all advertising gets funneled through a few businesses and independent publishers. Unless the United States rethinks its antitrust regime and expands the definition of “consumer welfare,” the monopolization of the economy will continue apace. After all, it’s been quite a week for Disney and Fox, too.

No comments :

Post a Comment