Of the five presidential elections Colombia has held since 2002, Senator Álvaro Uribe Vélez has now won four: two under his own name, and two more on behalf of his hand-picked candidates. Yesterday, that candidate happened to be Iván Duque Márquez, a one-term senator and longtime international development technocrat. Duque made it to Congress on the strength of Uribe’s closed-list ticket: you vote for all the candidates, or you vote for none of them. Now he will move to the Casa de Nariño, on the strength of Uribe’s coalition opposing the government’s ongoing peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). With stately grey hair, a decent singing voice, and a seemingly sincere passion for the virtues of market-friendly tax adjustments, the forty-one-year-old was not, as many critics argued, too young to govern. He was just young enough to be (relatively) untarnished by his to Álvaro Uribe Vélez—who, among a great many crimes, both proved and alleged, is currently being investigated for murder.

Uribe, the next Colombian president’s sponsor, left the presidency in 2010, when the Constitutional Court prevented him from extending term limits a second time. (Top Uribe ministers had bribed legislators to approve the first extension.) His administration was praised for bringing security to broad swaths of Colombia, which experts had predicted would become a failed state. Increasingly, it’s also remembered for illegal wiretapping and intimidation; extensive collusion with right-wing narco-paramilitaries; and the systematic murder of civilians to inflate the number of guerilla deaths the military could claim for its success metrics. Members of Uribe’s inner circle have been convicted of political crimes ranging from the essentially venal to deeply authoritarian. But Uribe himself has yet to fall, and the eponymous right-wing uribista movement is resurgent.

“I’ve never been a violent person. But don’t you see how many addicts and muggers and bums there are in the cities now?”In February, the Supreme Court began investigating Uribe for intimidating key witnesses—one of whom was later murdered outside Medellín—against him and his brother, Santiago, who is currently on trial for leading a death squad. The following month, Uribe’s Democratic Center party won a plurality of seats in the upcoming Congress; Uribe, the single most-voted candidate, will likely be Congress’s next president. In May, the U.S.-based National Security Archives released newly declassified evidence that Uribe launched his career with the support of Medellín’s cocaine mafia. Two days later, Duque won 40 percent of the first-round election vote. The week after that, the Supreme Court declared four incidents for which Uribe is being investigated—three paramilitary massacres during his governorship of Antioquia deparment and the assassination of the human rights lawyer who denounced them—crimes against humanity.

As a senator, former Bogotá Mayor Gustavo Petro held the first congressional debates into paramilitary politics in Antioquia. And it was, perhaps fittingly, Petro who Duque defeated to complete Uribe’s return to power. Running on an anti-corruption and ambitious social spending platform, Petro received 42 percent of the vote in Sunday’s runoff, more than any leftist in Colombian history but well short of Duque’s 54 percent. He made many mistakes during the campaign—it took Petro, a former political militant with the demobilized M-19 urban guerrilla movement, far too long to distance himself from the spiraling crisis in nearby Venezuela. But he lost, ultimately, because he presented too credible an alternative to Uribe. Reactionary business sectors incited fears of expropriation and capital flight. Major media reinforced the narrative of impending “Castro-Chavist” dictatorship. As soon as the field was narrowed to two, Colombia’s traditional political class lined up behind a candidate most voters only knew as el que dice Uribe—the one who Uribe says.

I spent the week before the elections speaking with Duque supporters in Uribe’s hometown of Medellín, Colombia’s second largest city, where Duque won 72 percent of the vote. Fear of Petro, “populism,” and the Castro-Chavist menace came up often, as did total faith for Uribe’s leadership. (“That gentleman has big, big balls,” said a street vendor hawking pirated DVDs across the plaza opposite the Mayor’s Office.) There was the devout Evangelical couple that warned me of Petro’s plan to close churches and impose “gender ideology” on young school children. A university student wearing a bright green polo shirt lectured on the economic benefits of cutting taxes for “job creators.” Some supporters refused to believe Uribe could be guilty of all the nasty things he’s accused of—“Fake News,” one middle-aged mother of three called it. But many others, like the small restaurant owner, “poor but hard-working,” from the paramilitary-ravaged Caribbean banana zone, believed the accusations and didn’t care. “I’ve never been a violent person,” said the owner. “But don’t you see how many addicts and muggers and bums there are in the cities now? When they did the social cleansings, all of that disappeared.”

Luz Elena Galeano remembers the day in October 2002 when the military invaded Medellín’s Comuna 13, the district she lives in.Tanks rumbled through the labyrinthine streets that line the Aburrá Valley’s lush western mountains. Helicopters hovered overhead. Patrolling next to the soldiers and policemen were men with black balaclavas and handwritten lists of names. “It didn’t matter who you were, if you were on their list or not,” says Galeano, the president of Madres Caminando por la Verdad, Mothers Walking for Truth, a local victims’ rights group. “If they caught you on the street, or felt like taking you out of your house, they did it. And then you disappeared. We were all guerrillas anyway, right?”

Uribe had assumed office that August, but it was Operation Orion that inaugurated his self-proclaimed era of Democratic Security. Ostensibly intended to root out leftist militias, the operation was coordinated by then-Defense Minister Martha Lucía Ramírez, Duque’s running-mate, and executed in conjunction with Diego “Don Berna” Murillo Bejarano, perhaps the most powerful drug lord in Medellín’s history. Galeano’s husband, Luis Javier Laverde, was not “disappeared” in the initial phase, as up to a hundred or more residents reportedly were. He was pulled off a bus in 2008, by the paramilitaries who stayed behind to control the local drug trade and protection rackets. Four years later, Galeano was forced to flee across the valley, her activism on behalf of victims having drawn death threats. “We were supposed to be the Laboratory of Peace,” she says, laughing.

In 2003, Uribe chose Medellín as a pilot site for the negotiated demobilization of Colombia’s national paramilitary structures. Don Berna made a mockery of the process, using it as cover to strengthen his control of the city’s underworld. But in a limited sense, Uribe’s peace worked. “Don Berna’s consolidation created the conditions for change in Medellín,” says Angélica Durán-Martínez, a political economist who studies patterns of drug violence. With no market competition, and a unified state security apparatus offering protection against their rivals, Berna and his paramilitaries disciplined the local youth gangs, reducing needlessly “visible” forms of bloodshed and allowing city officials to perform certain basic functions in neglected peripheral neighborhoods. Those seen as undesirable, such as drug users and queer people, were eliminated.

Once the world’s murder capital, Medellín famously became the World’s Most Innovative City. Today, an expansive web of cable cars will take you from the elevated metro line up the vertiginous mountain walls, at a safe, respectable distance from the zinc-roofed slums below. Along the shaded, boutique storefronts and cafes in Poblado, the only bodily fluid being spilled is the vomit of inebriated foreigners.

Beneath the renovated facade of the Medellín Miracle, extreme inequality remains, and other, less attention-grabbing forms of violence, like extortion, have proliferated. In 2008, Uribe ordered the secret, overnight U.S. extradition of Berna and 13 other top commanders who were reportedly preparing dossiers on his ties to the paramilitaries—setting off a prolonged power struggle between remaining factions. Galeano’s husband was taken soon after; she believes his body was disposed of in a giant trash dump at the edge of Comuna 13, along with those of some 300 other victims. Periodic turf wars continue to break out whenever the latest government-brokered truce breaks down. So far this year, there have been 32 murders in the Comuna 13 alone. “Everyone wants to talk about how good things are,” says Galeano. “They prefer to keep the truth buried.”

The first city in the country to industrialize, Medellín has long thought of itself at the forefront of Colombian capitalism. And in his eight years as president, Juan Manuel Santos—Uribe’s hand-picked man before Duque—has attempted to sell the world on an altogether similar national turnaround narrative. The demobilization of the FARC—and potential demobilization of the smaller, more volatile National Liberation Army (ELN), which agreed to a five-day election ceasefire as part of its talks with the Santos government—will do for the war-torn Colombian periphery what dismantling the Medellin Cartel has supposedly done for the city’s slums. Santos received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016, but the true vindication of his Third Way alternative (“the market wherever possible, the government wherever necessary”) came last month, when Colombia was invited to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Peace, said Santos, is “a necessary condition for our development,” for Colombia to become a truly “modern country.”

Santos’ falling out with Uribe is often reduced to an ideological disagreement over the peace process. But Uribe had himself pursued talks with the FARC rebels, on terms more lenient than those eventually offered by Santos. Santos’ betrayal was personal. He appointed a cabinet hostile to Uribe, and allowed prosecutions against his former allies to move forward. To the extent there was an ideological element, it was over the relation of brute force to their shared economic project. Santos had served as Uribe’s defense minister during the height of the war with the FARC. But he sensed that Uribe, with his open disdain for journalists and the basic rights of opponents, had become a liability, if not at home then abroad—that rampant state violence, while no doubt necessary to contain the guerrilla, was preventing Colombia from taking its place among modern, developed nations.

Some commentators have speculated that, like Santos, Duque might break with Uribe once in office, and govern like the centrist the hardliners in his own party have long suspected him to be. It’s unlikely for a few reasons: Duque does not have Santos’s mastery over backroom Colombian politics—and Santos did not have Uribe lording over his Congress, setting the legislative agenda. But the more important question is how meaningful such a break would even be.

“There are lots of groups that would bristle or would take moral offense at the notion that they are invested in the nastier side of development,” says Mary Roldán, a Colombian historian at the City University of New York. But when it comes down to it, the Santoses and Duques of Colombian history have always made peace with the Uribes and their methods. They understand, even if they would never admit as much, that “at the local level, these processes have only been possible through illicit forms of control.” Santos’s pro-peace governing coalition rallied around Duque, though it likely means the ultimate doom of their signature legislative project. They know how Uribe operates and what he represents, and they decided, in the end, that his protection was worth it. In a moment of economic precarity and profound social transformation, many Colombians have turned toward a “strong hand” they can trust—even, and in some cases especially, one that is stained in blood. Faced with the prospect of genuine institutional change, Colombia’s ruling elite have, as well.

Laura Bush, the former first lady, has never been particularly outspoken. So the political world took notice on Sunday when she expressed her displeasure at the Trump administration’s immigration policy. The separation of migrant children from their parents and guardians, she wrote in The Washington Post, “breaks her heart.” “Americans pride ourselves on being a moral nation, on being the nation that sends humanitarian relief to places devastated by natural disasters or famine or war,” she continued. “We pride ourselves on acceptance. If we are truly that country, then it is our obligation to reunite these detained children with their parents—and to stop separating parents and children in the first place.”

Bush is one of a growing number of prominent Republican women to criticize the administration’s policy, which has caused the separation of thousands of children in recent weeks and may result in as many as 30,000 detained children by August.

“As a mother, as a Catholic, as someone with a conscience … I will tell you that nobody likes this policy,” Kellyanne Conway told NBC News’ Chuck Todd on Sunday. Trump’s policy “is traumatizing to the children,” said Maine Senator Susan Collins. “Mrs. Trump hates to see children separated from their families,” Melania Trump’s spokeswoman, Stephanie Grisham, said on Sunday. “She believes we need to be a country that follows all laws, but also a country that governs with heart.” And conservative commentator S.E. Cupp tweeted a photo of her children on Saturday, writing, “I’m lucky. I got to hold this nugget in my arms. I still get to. Imagine you’re a mommy who can’t, because of this awful Trump policy at the border that rips children away from their families. THIS MUST STOP.”

One could dismiss some of these women as hypocrites. Bush’s op-ed, for instance, excludes the fact that it was her husband, George W. Bush, who created Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. Collins opposes a Democratic bill that would end the separation policy. Conway has yet to resign her position. But there’s another troubling facet to their rhetoric. With the exception of Collins, these women either explicitly or implicitly invoked their motherhood, as though this bestows a particular moral authority on them. Bush noted that her late mother-in-law, Barbara, once “picked up a fussy, dying baby named Donovan and snuggled him against her shoulder to soothe him” during the onset of the AIDS epidemic.

Motherhood no doubt gives a person a certain perspective on Trump’s separation policy. But everyone has been a child, and thus can imagine—or perhaps know firsthand—the trauma of being separated from a parent. When judging Trump’s policies, personhood grants all the moral authority that anyone needs.

The motherhood line serves another, older purpose: These tweets and op-eds and statements are also venerations of the nuclear family. They argue for the preservation of a specific social order, not for more equitable immigration laws. The role of the mother has long been one of the few positions of authority that conservatives have opened to women. But that authority is limited by default. For social conservatives in particular, the role of the mother is not one that women should be able to freely accept or reject; their abortion policies would force women into motherhood.

For this and for other reasons, an outbreak of concerned motherhood from conservatives does not necessarily constitute serious bipartisan opposition to Trump’s policy. A rush for allies in this debate—Democratic Representative Adam Schiff of California thanked her on Twitter for the piece—may well obfuscate the GOP’s true extremism on immigration. There’s no reason to hope that Conway will, as a mother or a Catholic, persuade her boss to change his mind. She’s had plenty of time to do that already.

Media outlets can publish all the Trump critics they want. Producers can put them on TV. Editors can give them jobs as columnists and commentators. But the Republican Party is still firmly the party of Trump, and this is the case because of his anti-immigrant crusade, not in spite of it. His influence is most evident in polls of immigration sentiment among Republican voters. According to a new poll conducted by The Daily Beast in conjunction with Ipsos, 46 percent of Republican voters approve of the family separation policy. Trump launched his campaign with a promise to build a border wall and while most Americans oppose the idea, a CBS News poll released in March says that 77 percent of Republicans support it. Meanwhile, Trump’s approval ratings are higher than they’ve been at any other point in his presidency.

The Republican Party is an anti-immigrant party. It has fully embraced Trump’s agenda. The depth to which the GOP has taken up the cause of immigration restriction is evident in Collins’s dithering; it’s clear also in a Monday statement released by moderate Republican Senator Ben Sasse. Family separation is “wicked,” he admitted, but he also called it “a bad new policy” that “is a reaction against a bad old policy.” It all started with “the stupidity of catch-and-release,” he said, referring to the policy of releasing migrants who have claimed asylum until their court hearing. How much reform can be expected from a party committed to the idea that immigration is a threat?

The Trump administration might eventually unite these separated families. Maybe it will even get kids out of detention cages into homes, where they can sleep in beds with real blankets instead of foil sheets. But what happens after that? A concentration camp is still a concentration camp, even if families get to share the same tent. Restrictive, excessively punitive immigration laws are still in place. ICE still exists. The administration will still send asylum-seekers back to face violence and death in their home countries. One need not be a mother, or a father, to understand why that must change.

One evening a few years ago, I saw an alarming scene unfold at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta. Amid the grimy seats, the unruly toddlers and their irritated parents sat two women and one man. All were of South Asian descent and bound like myself to a South Asian destination. They had been ahead of me in the security line as well, all of us thoroughly patted down and searched and glowered at before being permitted into the sanctum of the terminal itself. Now, the women, who unlike me were dressed in traditional clothes, drew the stares of nervous edgy travelers, all of being dutifully suspicious of anyone who dared depart from the requisite workout attire of the American traveler.

One of the women was crying. The other, who appeared to be her mother, comforted her. I could hear snatches of their conversation in Urdu. “I don’t know what to do,” sobbed the daughter. “He is your husband,” whispered the mother. The father said nothing. Around them, pre-boarding announcements were made, passengers clamored and were herded into numbered lines. Eventually, a ticket agent approached the family and began speaking to them in hushed tones. Her back was to me and her blonde ponytail bobbed up and down, she appeared to be counseling and comforting. “He will kill me” the young woman still wailed, this time in English.

Just when the last boarding group was called, an Immigration and Custom Enforcement Agent appeared. The ticket agent led him to the woman, who seemed even more terrified at this new development. “Are you claiming asylum in the United States?” he asked her. She must have said yes, for not long after, she was led away by the ICE Agent for likely processing. Her parents boarded the plane without her.

I thought of the woman this week, as news of Attorney General Jeff Session’s directive to deny asylum claims based on domestic violence. I saw many more like her when I worked as a lawyer at a domestic violence shelter. Weary and terrified, even of me, they would sit hands folded and gaze averted in my plain office. Then, when the door was closed, they would begin their stories, of beatings and rapes, torture and taunts all delivered by the men they had married. The effort of telling these stories would exhaust them, we would go through boxes of Kleenex, years of tribulations. Under Sessions disqualification of domestic violence as a basis for asylum, all of them would have to return to their abusers.

All American women now live in a country with an Attorney General who doesn’t believe wife-beating has to do with gender.There are only two ways of claiming asylum in the United States. The first, is directly at the border or port-of-entry, when an arriving person makes a claim and is usually taken into detention right away. The other is when a person who has made lawful entry into the United States based on a visa, decides to apply for asylum. The woman in the airport, and most of the women I saw while working at the shelter, belonged to this second category. In a landmark case in 2014, the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that a Guatemalan woman who would face domestic violence if she returned qualified as a “member of a particular social group”—one of two conditions, along with “reasonable fear of persecution”—which need to be met for an asylum claim. “Married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationship” the court ruled, constituted a particular social group. For the first time, gender was being considered in asylum law.

The decision in Matter of A-R-C-G et. al, when it came down, was cause for celebration. The dogged and bizarre refusal of past immigration courts to consider gender, an immutable characteristic that was the reason for certain sorts of persecution, seemed a vestige of a pre-feminist era. No one considered the hardline conservative Senator Sessions, who would through debacles of politics and personality cults, have dominion over the country’s legal system in just two years.

Inserting himself into the pending appeal of a 2018 case involving a Salvadoran woman that was to be heard by the Board of Immigration Appeals, Sessions this past week in his capacity as attorney general overturned the A-R-C-G ruling: Domestic violence victims could not be considered a particular social group. The violence the women suffered “was persecution based on private conduct” and therefore not actionable in the way public conduct would be. While law in a given country might confine a woman to her marriage or inadequately protect her within it, for violence to meet the legal threshold for asylum under Sessions ruling, there would need to be some specific proof that the State had been unwilling to act.

Around the world, there are loads of laws that make women vulnerable to extreme abuse in marital relationships. In the Philippines, where Catholicism exerts a strong hold over the legal system, divorce is not an option for a majority of citizens leaving women in abusive relationships for all of their lives. In India, a majority of courts do not consider marital rape a crime and therefore do not punish even those who may confess to it. Given all the other obstacles, such as family pressure, expense, court access that women already face and you have a set of legal strictures that leave women open to being regularly raped by their abusive husbands. Domestic abuse, in systems like these, is actively abetted by public policy: the system, in effect, is denying these women protection. But according to Sessions’s ruling, the abuse itself is not evidence enough of the state’s complicity.

Sessions’s ruling implies a particular view of domestic violence within the American system, as well. To make his point that domestic violence is a personal matter, the Sessions decision cited precedent from 1975, glibly ignoring, in the words of the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program statement responding to the ruling, “the understanding of gender-based violence that has developed in the intervening 43 years.” In past decades, one of the strides made by feminist legal scholarship has been to argue that domestic violence is not necessarily a “private” crime, but rather a deliberate act that targeting women because they are women. Overturning that understanding of domestic violence doesn’t just have implications for asylum law: All American women now live in a country with an Attorney General who doesn’t believe wife-beating has to do with gender.

In selecting immigration, and “other” women as a battleground via which both legal definitions and general legal understandings of domestic violence are transformed, Sessions has made a deft political calculation. The assumption behind it simply that because it is the fates of unknown women, at airports, in shelters or inhabiting the margins of the margins on the line, the rest of American women simply won’t care, imagining themselves inoculated by citizenship. The opaque and lugubrious language of the law is an unwitting accomplice in all this, the serpentine connections between precedents and statutes and sub-definitions shoving everything into abstractions.

The woman I saw at the airport that day was real, as have been the women that I saw while working at the domestic violence shelter. They were strong, but unsure about appealing to state authorities to help them. The governments they had known in Guatemala or El Salvador were governments of men, in the service of men. As an immigration lawyer, my first hurdle was always getting through the instinctive distrust that those who have suffered violence and persecution wear as armor. It took a long while to convince scared and abused women that the United States government would give their suffering due attention and care, making the significant hurdles of time and effort and paperwork worth it: New lives were possible for them, free of the constant threat or reality of violence.

I would not be able to make that promise anymore. Demoting domestic violence to private violence steps back toward the era when private violence was considered the business of private individuals, and the government had no business with it. In the past year, #MeToo victories have peeled away thick layers misogyny long preserved by institutional privilege. But U.S asylum law as it pertains to abused women is now subject to retrograde precepts, hacking away at women’s hard-won victories.

In 2001, after signing the papers that would finalize her much-publicized divorce from Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman emerged into the afternoon sunlight outside her LA lawyer’s office, raised her arms, and shouted for joy. At least, that’s the possibly apocryphal story behind an iconic set of paparazzi photos of Kidman looking triumphant in lime green capris and a sheer floral top that makes the rounds on social media every few months. The breakdown of Cruise and Kidman’s marriage is a familiar story: Stars are just like us, after all, and their divorce rates are even higher. But if celebrity marriages are more likely to end than ordinary ones, it may not be due only to the warping effects of fame. Like the star system itself, America’s version of the no-fault divorce was invented in California. (In the Soviet Union, the no-fault divorce had existed since 1918).

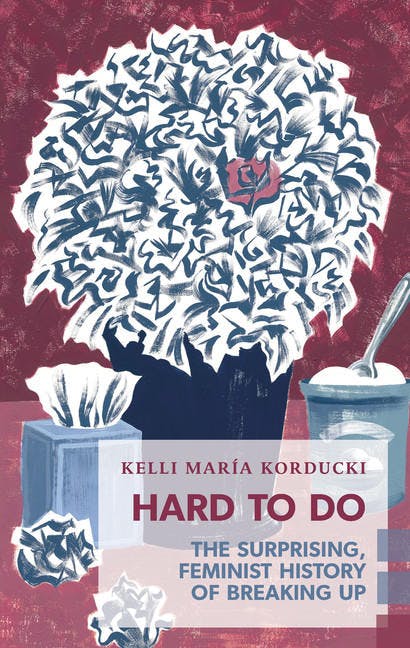

HARD TO DO: THE SURPRISING, FEMINIST HISTORY OF BREAKING UP by Kelli Maria KorduckiCoach House Books, 144 pp., $13.95

HARD TO DO: THE SURPRISING, FEMINIST HISTORY OF BREAKING UP by Kelli Maria KorduckiCoach House Books, 144 pp., $13.95Exactly 30 years before Kidman celebrated her newfound freedom, then-governor of California Ronald Reagan—himself a Hollywood divorcé—signed into law a piece of legislation that simplified the grounds for divorce: A couple could split because of “incurable insanity” or “irreconcilable differences.” The latter, as Kelli María Korducki writes in Hard to Do: The Surprising Feminist History of Breaking Up, “removed the requirement for a divorce petition to argue spousal wrongdoing on behalf of either partner,” a rule that had made divorce in America, up to this point, “a years-long legal hassle contingent on proving, through evidence provided and argued before a state court, a narrative of victimhood and perpetration.” That hassle had fallen most heavily on the shoulders of women, who were more often burdened with proving their suffering, and whose suffering was so pathologized it could be easily dismissed. (In 1836, a New Hampshire court refused to grant a divorce to a woman whose husband had locked her in a basement and beaten her with a horse whip because they alleged her “high, bold, masculine spirit” had driven him to it).

The no-fault divorce is just one of the turning points cited in Hard to Do, which charts the history of romantic dissolution in North America and the United Kingdom primarily through the legal and economic forces that have permitted women to initiate breakups—or, more often, prevented them from doing so. Korducki’s investigation is framed by the story of her decision to leave a “kind, sweet, smart and good” man she “had loved and lived with for nearly a decade.” It was not a decision made lightly; she consulted with friends, family, a therapist, and even a Dear Sugar column, in which a then-anonymous Cheryl Strayed advised three women at similar crossroads. Even so, the breakup “persisted in destroying [her] entire life over the course of many months.” Why, she wanted to know, did walking away feel “like scoring big in the lotto and torching your winnings for sport?”

Korducki’s choice of words here is pointed: Despite the gains women have made, the odds remain stacked against them when it comes to striking out on their own. Nicole Kidman memes aside, mainstream messaging about breakups is rarely so celebratory. A brief journey into the world of romantic self-help reveals a genre “conspicuously short on books that speak to a woman’s right to call it quits, let alone her desire to”—despite the fact that women who file for divorce report being happier afterward, while the opposite is true for men. When it comes to the question of women’s romantic autonomy, our cultural imagination remains limited. Hard to Do illuminates the capitalist logic that underpins intimate relationships, and asks what it would take for us to stop viewing breakups as failures.

The history of romantic partnership maps neatly onto the industrial and economic history of the last two centuries. Up to that point, marriage had been primarily a pragmatic institution: a legal union undertaken in the interest of preserving family wealth, property, bloodlines, and social classes. In fact, love—and desire in particular—was once seen as anathema to marriage; as Plutarch recorded in his Life of Cato the Elder, the Roman statesman Manilius was kicked out of the Senate for kissing his wife in front of their daughter in the second century BCE. But with the Industrial Revolution, alternative paths to wealth opened up and people flocked to new urban centers in pursuit of them, disrupting older kinship structures. Meanwhile, the Enlightenment encouraged the pursuit of individual rights and happiness. The love-marriage was born.

Still, courtship and calling, both of which occurred within the controlled space of the family home, remained the dominant form of socializing between young single men and women until the turn of the twentieth century. As Moira Weigel recounts in Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating (a kind of corollary to Hard to Do), the stock market crash of 1890 precipitated a great flood of women from rural or agrarian backgrounds leaving home to find work as garment workers, laundresses, salesgirls, and secretaries in the city, accelerating a wider population shift from rural to urban areas. By 1900, more than half of American women worked outside of the home.

This put working-class men and women in closer contact than ever before, on the job, in transit, and in the new spaces for leisure—the cinema, the soda fountain, the amusement park—that sprang up to absorb their pocket change. Because women, then as now, had less spending power than men, many would accept dates on the basis of a “treat,” earning them the nickname “Charity Girls” (along with lots of hand-wringing). “Where older models of courtship were structured around a ritualized exchange of domestic niceties,” Korducki writes, “dating was built on the public consumption of goods and services. Dating, in short, was good for the growing economy.” That remains true today when in the United States, the online dating industry alone generates $2 billion in revenue each year.

If marrying for love and mixed-gender fraternizing outside of the home are relatively new, splitting up has even less precedent. Divorce remained exceedingly rare until the first liberalizing laws of the nineteenth century; breaking up in the more colloquial sense is not even a century old. The lean years of the 1920s and 30s had encouraged a competitive model of dating that was not necessarily seen as a precursor to marriage: while the ability to afford sodas, hamburgers, and Vaudeville tickets had set daters apart in the early 20th century, during the post-Depression years, dates themselves became a kind of currency. “Dating prolifically was the one way to keep up their stock,” Weigel writes, “even as any given date became less likely to lead to a permanent arrangement.”

It was only with the economic boom of the postwar years that the break-up came into being. Suddenly, many young men and young women had the means to pay for a night out, and the importance of telegraphing popularity by racking up dates waned. This created what Weigel calls “a kind of romantic full employment.” Rather than filling their date books and dance cards with as many potential partners (and potential “treats”) as possible, young people began pairing off. “Steadies invented the Breakup,” Weigel argues. “Going steady was a prerequisite for that specific kind of heartache.” In an era where breakups furnish lucrative apps, reality TV concepts, Hollywood blockbusters, and entire music careers it comes as something of a revelation that we’ve only been doing this for some 60-odd years.

The official history of marriage and dating, Korducki points out, has also been an exceedingly white, heterosexual one. In the antebellum South, enslaved black men and women were legally considered property and were unable to formally marry at all; although informal marriages among enslaved men and women were common, an estimated two-fifths of these partnerships were forcibly broken up by the domestic slave trade. At the turn of the twentieth century, vice commissions frequently dispatched undercover officers to observe young men and women meeting up for dates (under the assumption that they were engaging in prostitution), but this surveillance paled in comparison to the violence those same officers frequently enacted in clandestine gay spaces. As Korducki puts it, “though we’re all inheritors of a history, some of us have longer threads on the rope’s frayed end.”

Still, with the admission the conversation might feel dull for anyone whose partnership choices have always been considered transgressive, Hard to Do speaks mostly to Korducki’s cohort, and my own: unmarried, heterosexual millennial women living in cities with at least a modicum of “disposable income and expendable time.” The unprecedented freedom such women now have to make or break relationships has raised the stakes, she reflects, when it comes to selecting a partner: “With autonomy comes great responsibility to either choose exactly right or to undermine the very existence of our own freedom to follow our hearts.” If there are now more methods of pairing up than ever, and more time in which to do it, there are also more ways to get it wrong. Such mistakes carry more weight in an increasingly atomized society, in which romantic partners are expected to fulfill multiple social and emotional needs—consider the ubiquity of the phrase “I can’t wait to marry my best friend!”

Of course, much of this freedom is illusory: While it’s become gauche to acknowledge explicitly the relationship between money and, well, relationships, the economy still exerts a powerful influence on our romantic lives. Dating apps like The League that cater exclusively to an “elite” clientele, but even the less exclusive ones tend to match people on the basis of shared tastes—in film, food, travel, or music—which tend to indicate class. And although women can now drink in bars unchaperoned and get a divorce, precarity continues to keep women in bad relationships. When unemployment rises, divorce rates drop proportionally. In an economic system that pays women less for their work than it pays men, sometimes leaving is just not financially viable.

Korducki, for her part, seems to have found, at least partly, what she wants. In the years since her breakup, she has moved away from organizing her life around a single romantic partner. In the book’s conclusion, she recounts instead the variety of relationships she now has: some intimate, others civic or neighborly. It’s a tentative step towards a different kind of future, one in which the emotional pressure we currently apply to romantic relationships is distributed more evenly across a wider social network. A future, in other words, that would render this book’s title moot.

No comments :

Post a Comment