President Donald Trump rarely caves to his critics, especially when it comes to the anti-immigration policies that form the core of his agenda. His proposed travel ban targeting Muslim-majority countries drew widespread condemnation last year, but he refused to back down, rewriting the proposal twice so that it might withstand judicial scrutiny. He also continues to insist that Congress provide substantial funding for his border wall, threatening on Monday to shut down the government this fall if he doesn’t get his way.

But the uproar caused by his policy of separating migrant children from their parents, and locking them in cages, proved too much for the famously stubborn president. Even congressional Republicans, who rarely offer substantive pushback to Trump, began working on legislation to reverse it. So on Wednesday he signed a new executive order, passive-aggressively titled “Affording Congress an Opportunity to Address Family Separation,” which instructs immigration officials to “maintain family unity, including by detaining alien families together where appropriate and consistent with law and available resources.”

In theory, that means families who are apprehended after crossing the border illegally will now be detained together instead of separately. However, the order does not outline efforts to reunite the thousands of families who have been broken apart recently, nor does it indicate how long migrant families going forward will be detained. It appears the administration is seeking the right to detain them indefinitely.

The courts will have their say, though this time it’s because the administration is actively seeking judicial clarity rather than being forced to defend itself against lawsuits. Trump’s order calls for the Justice Department to ask a federal court in California to modify a 1997 consent decree known as the Flores agreement, which outlines how long the federal government can detain migrant children, to allow the government “to detain alien families together throughout the pendency of criminal proceedings for improper entry or any removal or other immigration proceedings.”

Changing the Flores agreement would be a notable change in federal immigration policy. As Vox’s Dara Lind and Dylan Scott recently noted, the agreement was the result of a legal battle over the treatment of migrant children in the 1980s, and its terms require federal officials to keep those children in the “least restrictive setting” possible for as little time as possible with adequate access to food, water, and medical care.

The Trump administration has cited the Flores agreement as an obstacle that forced it to pursue family separation. In 2016, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that immigrant children could only be detained for 20 days before they must be released. But earlier this year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy, which requires federal prosecutors to seek criminal charges against anyone who crosses the U.S. border with Mexico without authorization. Because every adult who is caught crossing the border illegally is now being detained and prosecuted, and children cannot be housed in U.S. jails, the Trump administration says it had no choice but to separate the families.

This is a false choice, however. Officials could simply release migrants pending their immigration hearings, as past administrations have done. BuzzFeed’s John Stanton noted that, contrary to the administration’s hyperbole about lawlessness at the border, almost 90 percent of released migrants appear for their hearings.

Detaining families indefinitely is a solution in search of a problem. Depsite claims by AG Sessions et al that releasing migrants is de facto amnesty, federal data shows the vast majority of people released show up for their immigration hearings.https://t.co/QZNqg6FeaP pic.twitter.com/K9ppXXxOTL

— john r stanton (@dcbigjohn) June 20, 2018By seeking to modify Flores in federal court, Trump will force one of two outcomes. If successful, he will have a modicum of judicial cover for indefinite detention of migrant families. If unsuccessful, he can blame the judges responsible for that decision, as he has done so many times before. The overall policy—using cruel and draconian measures to deter asylum-seekers from traveling to the United States—would remain intact.

“The devil is in the details,” Anthony Romero, the ACLU’s executive director, said in a statement. “This crisis will not abate until each and every single child is reunited with his or her parent. An eleventh-hour executive order doesn’t fix the calamitous harm done to thousands of children and their parents. This executive order would replace one crisis for another.”

Trump’s executive order is not a policy solution for the resurgent migrant crisis. It’s a slapdash legal gambit that, even if it survives judicial scrutiny, may well create a horror of another sort: massive concentration camps on America’s southern border. But if that happens, Trump already knows who to blame. “It is unfortunate,” his order says, “that Congress’s failure to act and court orders have put the Administration in the position of separating alien families to effectively enforce the law.” In reality, Trump bears full responsibility for the cruelties being committed to enforce his immigration policy. And if his latest move creates yet new cruelties, those will be on his head, too.

The outcry that has greeted Donald Trump’s initiative to separate immigrant children from their parents at the U.S. border has been propelled by a series of images, recordings, and reports in the media. We have seen photographs of wailing children, in cages or all alone; we have heard them cry. Their terror and sadness is overwhelming to witness. Though the Ann Coulters of this world claim that children can “act” on screen to manipulate the public into opposing Trump’s policy, this is not true. A four-year-old cannot act.

The power of this kind of media lies in that authenticity. When John Moore took his now-viral photographs of a two-year-old girl at the U.S. border, “he understood at once that they were the photos he had been waiting for—for hours, if not years,” The Washington Post reported. The baby would become an image that changed something—maybe not for her but perhaps for others, if not the underlying policy, the way Americans viewed their government. It is natural for adults to want to protect innocent and helpless children, particularly those who have been made helpless by powerful political actors in the White House. Their cries represent a rare moment of genuine emotion in the shiny and false theater of American politics.

But the ethics of a “poster child” campaign are not as straightforward as many in the media are making out. Sharing a photograph or a link creates awareness and churns outrage, but it also defines the debate in ways that obscure the root problem. The immediate question is the fate of these children; the immediate enemy is a depraved White House. The larger challenge, however, requires a compassion that is broader than what a single child can invoke.

Poster children have proliferated in media coverage of political crises in recent years. Little kids in Iraq (Samar Hassan, 5, living), in Syria (Omran Daqneesh, 5, living), and on migration routes through Europe (Alan Kurdi, 3, dead) have become potent symbols that have produced reactions in the West that images of adults have not. This type of coverage has long roots, from Nick Ut’s famous image of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc running along a road after being burned by napalm, to the starving children of Ethiopia in the 1980s.

These images connect to the long history of western philanthropy for children. The charity sector, for example, abundantly uses small children to provoke bourgeois pity. In the early 1980s, a campaign by the U.K.’s Disasters Emergency Committee drew attention to the famine in East Africa by using a photograph of two emaciated children eating, under the headline “THEIR LAST MEAL.” Donors gave $23 million in response.

John Moore/Getty Images

John Moore/Getty ImagesThese poster children present a paradox: They are real, so is their suffering—but they have also been chosen to represent a suffering that is shared by many others. A stark example is the “sponsor a child” style of philanthropy, where a charity like Save the Children pairs the donor with an individual recipient of your funds. The donor can even choose the child from a list of photographs. In Bleak House, Dickens caricatured this kind of humanitarianism in the character of Mrs. Jellyby, who obsessively advocates for a faraway population but neglects to care for her own kids. His critique was that the Jellybys of the world sometimes commit the sin of simony, meaning that they trade in sacred and spiritual materials for their own emotional profit.

There are several political repercussions of allowing a single child to represent a crisis. The first is that the child herself, literally voiceless in the case of Moore’s photograph, ceases to be an individual. She instead becomes a blank canvas upon which adults project their anxieties and fears. The second is that it obscures the suffering of others—particularly adults. Moore’s photograph captures this young migrant’s isolation so well that it hurts; but, by definition, it leaves out the faces of the rest of her family. It reduces a crisis about human beings of all ages and stages of life to a single image of total vulnerability.

Behind the American response to these images of children lurks an uncomfortable truth: The white majority in this country perceives children of color differently than they perceive adults, in what we might call the visual rhetoric of victimhood. This crisis is happening to babies, toddlers, teenagers, parents, and elderly adults; but the only images that can make America care about its inhumane policy toward immigrants at its borders, the only images that can cause a Republican like Laura Bush to speak on behalf of these foreigners, are photographs of children.

Just as in the advertisement seeking funds for the famine in Ethiopia, these are not false images: They depict real pain. But justice still lacks for a suffering child if that child’s total helplessness is the only thing that can move people. When people pity a baby who has no political agency, the baby becomes an image through which people express anxieties about their government in a different way than if they had to respond to an adult’s autonomous speech. It’s not a conversation.

Perhaps the “poster child” media syndrome will always function as a catalytic stage. First, we see the baby; the baby’s cries then connect to some animal part of our hearts, which in turn activates the conscious parts of our minds. But, relying too much on the heart to do political work around immigration is like relying on baby polar bears to get people to care about climate change; it’s a limited strategy, and it limits our understanding. There’s an adage in social justice advocacy to remind us that victims shouldn’t have to exhibit their trauma to gain respect and understanding: Exhibited suffering breeds empathy, but it turns the traumatized into a spectacle. Migrants at the U.S. border need agency, urgently. And to facilitate that Americans need to listen to what they have to say. An infant can scream, but she cannot speak.

“Democrats are the problem,” Donald Trump tweeted on Tuesday. “They don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country, like MS-13. They can’t win on their terrible policies, so they view them as potential voters!” Like many of Trump’s tweets, this statement contains both a lie and a slur. The Democratic Party bears some responsibility for the Obama administration’s immigration policies—humane and restrictionist alike—but it did not create the zero-tolerance policy that now breaks up families at the border. That policy belongs to Trump; he will be remembered for it, and for the rhetoric he has used to justify it.

“Infest” is not a word customarily used in reference to humans. We fear infestations of cockroaches or bedbugs or lice. To accuse people of infesting America is to dehumanize them.

This is not the first time Trump has referred to migrants in this way. Sanctuary cities, Trump once complained, are “crime-infested,” as if the presence of immigrants guarantees an outbreak of violence. He is also worried about their “breeding,” a word usually reserved for animal or insect mating: “Soooo many Sanctuary areas want OUT of this ridiculous, crime infested & breeding concept,” he tweeted in April.

Trump did not invent this language from whole cloth. Modern history is full of examples of political regimes that has described certain populations as subhuman—often to justify treating them as such. In the most extreme cases, that rhetoric preceded mass killing.

“One of the common threads of any genocide is its justification. In order to be able to execute it on a mass scale, a lot of people have to buy into it and agree that it’s the appropriate thing to do. And so any any genocide begins with the dehumanization process,” explained William Donohue, a professor of communication at Michigan State University who has studied the function of dehumanizing language in the Rwandan genocide.

In one influential speech, a Hutu politician compared Rwanda’s Tutsi population to a particularly nasty insect. As Foreign Policy reported, Leon Mugesera in 1992 “told a crowd of supporters at a rally in the town of Kabaya that members of the country’s minority Tutsi population were ‘cockroaches’ who should go back to Ethiopia, the birthplace of the East African ethnic group.” Mugesera is hardly the only reason the Hutu people started slaughtering the Tutsi two years later; he was one powerful propagandist in a generation of propagandists. But radio broadcasts disseminated this language to radical Hutus and, in the opinions of human rights tribunals and experts like Donohue, spawned mass violence.

Nobody in the Trump administration has called for the killing of migrants. Violence is not government policy, but rather a side effect of policy; the U.S. government deports migrants back to their home countries, which many have fled out of fear of being killed by gangs or abusive husbands. There is no race war. Nevertheless, words like “animal” and “infest” perform pernicious political work in any context. “Any time you use any of those metaphors, it’s meant to try to reduce sympathy for a particular group, so people see that group as not deserving of compassion. It’s a kind of objectification,” Donohue said.

Considered alongside the spectacle of human beings in cages and camps and “tender age” shelters, Trump’s language has inspired comparisons to the Third Reich. “This is the United States of America; it’s not Nazi Germany,” Senator Dianne Feinstein of California told MSNBC’s Chris Hayes on Monday. It’s a controversial metaphor, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions vehemently rejected it on Monday evening: “In Nazi Germany, they were keeping the Jews from leaving the country,” he said.

It is fraught to make any comparison to the Nazis, as it threatens to dilute their unique horrors. But Andrea Pitzer, author of One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps, considers it accurate to refer to Trump’s government-run detention camps as concentration camps and sees other parallels between America today and Germany in the early 1930s. “What’s often forgotten is that nearly five years passed before the government arrested German Jews en masse and put them into the concentration camp system. Outside the camps, the Nazis were passing laws against German Jews the whole time, stripping them of citizenship and denying them access to public services and jobs,” she wrote in an email to The New Republic.

To build public support for their anti-Semitic policies, the Nazi government constructed an elaborate propaganda machine. White, German families were presented as whole and hearty—and under threat. “In their rhetoric, Nazis talked about Jews using animal terminology (of rats, insects, and pigs) and as unassimilable foreigners, and described them using language of disease and sexual deviance,” Pitzer continued. The Eternal Jew, an anti-Semitic propaganda film released in 1940, compares a map of Jewish migration to a pulsating pile of rats; Jews weren’t just considered animals, but plague-bearing animals at that.

Republicans have not compared immigrants to rats, though a New Jersey official once bizarrely compared them to raccoons. America is not Nazi Germany; it is not Rwanda in 1992, perched uneasily on the edge of an abyss. If parallels exist, it is because prejudice often uses a common language. “The rhetoric of hate is portable and flexible—it can be used anywhere against anybody,” Pitzer wrote.

The United States has its own history of dehumanizing populations in order to enslave and massacre them. Thomas Jefferson once compared enslaved Africans to wild animals, as Nicolaus Mills noted at The Daily Beast. “But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other,” Jefferson wrote in 1820. The widespread belief that Africans were not fully human, but rather subhuman, propped up the Confederacy’s defense of itself. Abraham Lincoln, one Alabama commissioner wrote at the time, would consign the South’s “citizens to assassinations, her wives and daughters to pollution and violation, to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.”

In a similar fashion, the idea that Native Americans are subhuman propelled not only a campaign of slaughter against them, but a program of forced migration and a system of boarding schools intended to force assimilation on their children. President Andrew Jackson, defending his government’s removal policy, bragged, “It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from

the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude

institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them

gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast

off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

Trump started down Jackson’s path on the day he launched his campaign, when he referred to Mexican as “rapists” coming over the border, and he inched closer toward today’s border camps with every rant about “bad hombres” and MS-13 “animals.” As Jamelle Bouie argued for Slate on Tuesday, “The ‘animal’ comments help explain his core beliefs, which his recent remarks make crystal clear: President Trump sees all Hispanic immigrants—and not just MS-13—as ‘animals’ threatening the cultural and racial integrity of the United States.”

It isn’t wise to fearmonger. But it’s important to remember how violent rhetoric can lead to violent outcomes—so can concentration camps. “I went into Rohingya camps in Myanmar in July 2015 and also interviewed locals in town who supported their segregation,” Pitzer wrote. “I was struck by two things: the first was how similar the extremists’ rhetoric was to 1930s Nazi propaganda, and also how similar it was to the things Donald Trump was saying in the first weeks of his campaign, which began not long before my trip.”

When it comes to winning elections, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan appears to be a master. He and his conservative Justice and Development Party, commonly known through the initials AKP, have dominated every Turkish election since 2002 with impeccable political timing and adaptation.

In 2002, taking advantage of the growth opportunity for emerging markets, Erdogan turned on his renowned charm and spoke about not only economic growth and opportunity but increased civil liberties and individual rights. More recently, as anti-Muslim sentiment and populism spread throughout the world, Erdogan dug into the authoritarian playbook and rolled out policies “to protect” Turkey and Turkish identity. That has included curbing the press, shutting down social media, jailing political opponents, antagonizing the Kurds, and using a failed coup attempt in July 2016 to impose a state of emergency. Nine months later, he managed to win a referendum to change Turkey’s constitution, giving the winner of the next election vast powers of an “executive presidency.”

In anticipation of further economic decline, Erdogan cannily moved Turkey’s next elections from November 2019 to this Sunday, June 24 two months earlier. His reasoning, presumably: to sidestep economic discontent and the vicissitudes of the youth vote. According to the Turkish polling company, Konda, out of 57 million voters about 19 million are under 32. Half of them say that they don’t support any party.

But as opposition parties seize the moment, mounting a formidable coordinated challenge with the very tactics that catapulted the Turkish president to power, it finally seems the master may have miscalculated.

Erdogan has profited in the past from a persistently weak and pathetic opposition. Few of Turkey’s half-a-dozen opposition parties have been able to put forward a convincing platform, much less a convincing leader. This is particularly true for the main opposition People’s Republic Party (CHP), the party of the founder of the Turkish republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

In March, the AKP-dominated parliament passed a bill that enabled political parties to run as part of a coalition, circumventing the requirement that an individual party achieve a 10 percent of votes into order to enter parliament. The AKP did so to avoid a repeat of the June 2015 election results, when the party garnered a plurality of 40 percent and, hence, lacked the necessary majority to form a government. Hence, in collaboration with the National Movement Party (MHP) and the Great Unity Party (BBP), it formed the People’s Alliance—Cumhuriyet Ittifaki.

In response, four opposition parties, led by the CHP, formed the National Alliance—Milliyet Ittifaki. It includes an offshoot of the nationalist MHP, led by the dynamic Meral Aksener—one of the few women in Turkish politics. Together, they have embraced a united platform focused on the very issues that catapulted Erdogan to the prime minister’s seat in 2003—minority rights, democratic freedoms, and the economy.

Turkey’s economy has been on the decline since the global financial crisis in 2008. Foreign investments that once flooded the country have dried up and the growth that propelled Turkey into the G-20 has slowed. A combination of a rising U.S. dollar and market uncertainty about Erdogan’s monetary policy, including unorthodox beliefs about high interest rates causing inflation, has led to the Turkish lira dropping one fifth of its value in the past year. Turkish unemployment has been on a steady rise since 2012, standing over 10 percent.

In response, the once economically adept Erdogan has spoken about opening up “kiraathanes”—reading houses with free coffee, tea, and wifi. It is a far cry from his old policies focusing on job creation, trade expansion, and entrepreneurship. Instead, it is Muharrem Ince, the CHP candidate and a former physics teacher, that speaks about revitalizing manufacturing, expanding agriculture, and bringing back jobs to Turkey through policies that would attract both local and foreign investors and skills training for Turkish youth.

Ince, along with his counterparts in the National Alliance, also speaks about religion, diving into an area that Erdogan one ruled: identity politics. Given how weak the country’s institutions and rule of law are, Turks have voted for politicians they feel represent and resemble them ethnically and religiously. Erdogan once gave voice to minorities, particularly the Kurds, along with the majority that embrace Islam as part of their daily lives. Today, Ince and the National Alliance speak about teaching Kurdish as a second language, praying, and embracing women in headscarves as our “sisters.” The media has made much of the fact that Ince’s sister wears one.

In 2002, Erdogan frequently spoke about growing up in a working-class neighborhood in Istanbul and representing the “black Turks”—the long-ignored, largely rural and traditional underclass that Turkey’s secular “white Turk” elite spurned. Today, Muharrem Ince, who like Erdogan hails from Turkey’s Black Sea region, dives into crowds to folk dance and eschews scripted speeches in favor of fiery rhetoric about a Turkey for “the common man.”

Erdogan, however, still holds many of the cards in his favor. Media is largely under state control, giving enormous airtime to Erdogan and his message and little to anyone else. Erdogan has made it difficult for Kurds, who hold 19 percent of the vote, to get to polling stations. Out of concerns for “security,” Turkey’s High Electoral Board (YSK) relocated polling stations in the Kurdish-dominant southeast. Over 100,000 voters will have to travel further and across precarious roads to reach the ballot box.

Erdogan is also a known figure, with an impressive track record. That matters in a country in which trust lies in the “man.” The question Turks will have to answer on Sunday is whether that man, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has worked to garner unprecedented power, should go ahead to rule alone. At stake is the transformation of Turkey’s government, which voters in 2017 narrowly voted to move from a parliamentary system to a presidential one. That makes this election not just vital for the next few years in Turkey, but the country’s entire future.

It’s far from certain that Democrats will retake the House of Representative in November. Yes, the president’s party typically loses seats in Congress in the first midterm elections after his election, and American liberals are unusually motivated this year. Nonetheless, it’s possible that President Donald Trump’s strategy of riling his base over immigration, combined with structural advantages like gerrymandering, will allow Republicans to withstand what would otherwise be a blue wave.

But let’s say Democrats manage to eke out enough seats to retake the House, and perhaps even the Senate. Will they follow the Republicans’ lead by wielding their legislative power to the fullest possible extent? Will they rely on obstruction and delaying tactics to constrain the Trump administration as much as the Constitution allows?

The answer appears to be no. In recent months, some Democratic lawmakers have even suggested that instead of exerting maximal political force, they may try to diminish their own power.

The New York Times reported last weekend on a reform effort by a group of congressmen that unironically calls itself the Problem Solvers Caucus. The 24 Republican and 24 Democratic members of the group are hoping to revivify the House’s moribund legislative process and bring a spirit of bipartisanship to the chamber. To that end, they’re backing a set of proposed rule changes called “The Speaker Project,” put forth by the bipartisan group No Labels.

Some of the proposals are worthwhile: ending Congress’s ban on earmarks, which were denounced by good-government folks for years but actually served a useful role in the legislative process; holding regular Q&As between presidents and lawmakers, similar to the British Parliament’s weekly Prime Minister’s Questions; and allowing congressmen to anonymously force up-and-down votes on popular legislation, thus circumventing the House speaker without incurring his wrath.

But the central proposal—to require that a speaker be elected with bipartisan support—would impose a major hurdle for a Democratic House majority to overcome before it can govern.

“The next Congress should change the rules for electing a speaker,” No Label’s centrist manifesto states. “The new minimum number of votes required should equal the majority party’s total membership plus five. Theoretically, this could require a speaker to win support from only five opposition party members. But in recent years, several House Republicans and Democrats have refused to back their party’s nominee, so it’s quite possible that a would-be speaker would have to win the backing of numerous minority party members.”

That’s possible, but the more likely result—if the past decade is any indication—would be greater obstruction in the House. This proposed rule would allow a unified Republican minority to effectively veto any potential Democratic speaker, even if that person had received an overall majority of the votes from House members (by receiving every Democratic vote). Cynical observers may also note that since the House’s rules are rewritten after every election, there’s no guarantee that a future Republican majority would allow Democrats to exercise similar influence over a position that’s third in line for the presidency.

This isn’t the only example of Democratic self-sabotage that’s been floated in Washington recently. Earlier this month, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Minority Whip Steny Hoyer said they would adopt “pay-go” rules if they retake the House this fall. Short for “pay-as-you go,” the rules would require House lawmakers to offset spending increases with other spending cuts or higher taxes. Pay-go is meant to enforce fiscal discipline in Congress, though it mainly works to constrain Democratic-supported social programs.

Indeed, what makes pay-go so bizarre is that Democrats seem only to impose it on themselves when in power. Even Republicans who bill themselves as champions of fiscal restraint simply ignore it to pass their policy priorities: The GOP-led Congress approved a pay-go waiver last year before passing a massive $1.5 trillion tax-cut bill. Abiding by the rule would make it harder for Democrats to push for Medicare for All or other ambitious policies without dealing a severe blow to other vital programs.

Some Democrats have also suggested they would restore procedural mechanisms that would allow Republicans to block judicial nominees. In May 2017, Massachusetts Senator Ed Merkey said that he would support re-instituting the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees after the Republicans killed the rule to confirm Neil Gorsuch. Some other senators seem receptive to restoring blue slips, an arcane Senate tradition for blocking certain presidential nominations, which Republicans have disregarded under Trump.

The practice’s precise contours has varied over the years, but it generally works like this: Senators receive blue slips of paper with the name of presidential nominees for certain positions in their home state. If the senator approves, they return it to the relevant committee and the nomination advances. If they don’t return the slip, the nomination stalls.

The blue-slip tradition historically gave senators some measure of individual control over nominees for federal posts in their home states. But it also has a more bare-knuckled past. In the 1950s and 1960s, some Southern senators used the slips to block judicial nominees who would be favorable to desegregation. More recently, Republican senators used blue slips to hold up many of the Obama administration’s judicial nominees when Democrats controlled the Senate.

When Trump took office, Republicans then quickly set about filling as many of those vacancies as possible. Last November, Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, began allowing nominations for the federal circuit courts of appeal to advance even if blue slips weren’t returned. Overall, Republicans have approved Trump’s federal appellate judges at a faster rate than any president since Ronald Reagan. Since the Supreme Court only takes up a handful of the petitions it receives each term, these lower-court judges are often the final arbiters for thousands of federal cases every year.

Now that Republicans have largely discarded the blue-slip tradition for federal appellate judges, there’s no reason why Democrats should abide by it. Nonetheless, some leading Senate Democrats have continued to speak favorably about the practice. Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy, a former Judiciary Committee chair who abided by the practice during Obama’s presidency, gave a laudatory speech about blue slips on the Senate floor earlier this year, as did Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

“The blue-slip tradition has always been obeyed, we didn’t change that,” Schumer said on the Senate floor in May. “We could have. We could have stuffed through our nominees with no Republican input, but we didn’t.”

The placid approach is striking when compared to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who has wielded his office like a sledgehammer for partisan gain. McConnell blocked the Senate from even considering Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to fill a Supreme Court vacancy in 2016, all but handing the seat to Trump. He also single-handedly halted a bipartisan effort to shield special counsel Robert Mueller from being fired by Trump. Paul Ryan, the outgoing House speaker, also carries significant influence over his chamber’s legislative process, though the hard-right House Freedom Caucus has often limited his practical ability to pass legislation.

The solution to such legislative extremism isn’t for the other major party to become even more accommodating; killing one’s opponents with kindness doesn’t work on Capitol Hill. If Democrats win the House this fall, they’ll have many urgent issues to address—starting with the question of whether to impeach the president. If Democrats win the Senate, they’ll have Trump’s conservative judicial overhaul to contend with. Their voters will expect this of them. But if Democrats aren’t willing to exercise political power to advance their agenda, why should voters give it to them?

In April, President Donald Trump signed a declaration to create the first-ever National Foster Care Month. The month of May, it said, would celebrate those who provide temporary homes to children without parents or guardians. But May would also recognize a darker reality—“the plight of innocent children who are in foster care because their lives have been disrupted by neglect or abuse.”

Today, the American foster care system is bracing for an influx of children whose lives have been disrupted by the Trump administration itself. According to a Monday report from the Washington Examiner, approximately 250 migrant children are being taken from their parents or guardians per day as a result of Trump’s new family separation policy. If that trend continues, as officials expect it to, around 30,000 children would be in the government’s custody by August. That figure doesn’t include the thousands of minors who show up at the border without a guardian every month, a number that has increased significantly in 2018.

The Trump administration insists these kids will be alright. “The children will be taken care of—put into foster care or whatever,” White House chief of staff John Kelly told NPR in May. That’s exactly what’s happening. “As the Trump administration takes more migrant children into custody at the Mexico border,” The Washington Post reported last month, “new statistics show the government is placing a growing number in long-term foster care, sometimes hundreds of miles from their jailed parents.”

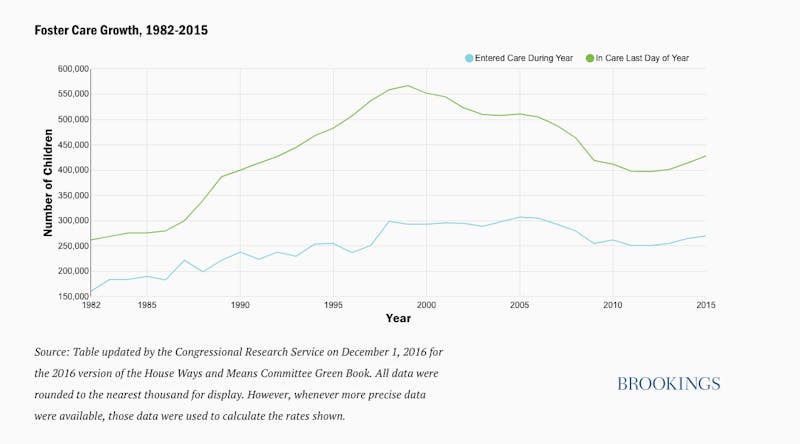

But the foster care system is already struggling to provide stable living situations for the 500,000 children who need assistance. The number of kids entering the system has increased every year for the last four years, but there hasn’t been a concomitant increase in social workers to help them and group homes or families willing to take them in. “American foster care,” the Post reported last year, “is in crisis.”

Trump responded to this growing problem in February by signing into law a massive overhaul of the system that redirects funding and resources for foster care services toward programs that keep children with their parents. But what about children whose parents have been jailed or deported by immigration officials? Can a strained system designed for abused and neglected American kids handle an influx of child migrants who are struggling with their own unique problems?

Unlike their parents, children apprehended at the border can only be legally held in immigration detention facilities for three days. After that, they must placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement. While ORR employees search for permanent placements, they put the kids in temporary shelters run by outside contractors.

Children forcibly separated from their parents are legally considered Unaccompanied Alien Children, a designation normally reserved for kids who show up at the border by themselves. According to HHS data, these children spend an average of 51 days in temporary shelters. Eighty-five percent eventually ended up in “sponsor homes” with U.S.-based relatives. About 10 percent wind up in foster care.

Children of Central American asylum-seekers watch TV at an immigrant shelter on April 25 in Tijuana, Mexico.John Moore/Getty Images

Children of Central American asylum-seekers watch TV at an immigrant shelter on April 25 in Tijuana, Mexico.John Moore/Getty ImagesThe White House insists the statistics will be different for the separated children; that they’ll returned to their parents within five to ten days. But that’s not how things are playing out in reality, said Sandy Santana, the executive director of Children’s Rights, one of the organizations suing the Trump administration over its separation policy. “We’ve heard stories of parents being deported and their children being left behind,” he said. “And then kids are being sent all over the country, and that distance makes it less likely that these reunifications are going to take place quickly. So our fear is that many of these children will linger in foster care.”

That may be happening already. A Seattle foster care facility, for example, recently accepted six children who were separated from their families at the border. And Michigan foster care agency Bethany Christian Services has helped place 58 separated migrant children since May 1, a representative said. That’s a major increase from January, when BCS only placed one separated migrant child. Today, children impacted by Trump’s policy make up 75 percent of the agency’s caseload.

Other organizations say they haven’t served any affected children. “We really haven’t been impacted,” said a spokesperson for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. But that’s because that group only provides resources for more permanent, long-term foster care. “We don’t really have any short-term, transitional sites,” he said.

But some separated migrant children will eventually end up in long-term foster care, former head of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement John Sandweg said in a Tuesday interview with NBC News. “Permanent separation. It happens,” he said, adding that Trump’s policy “could be creating thousands of immigrant orphans in the U.S.” He added that long-term separations normally happen because parents are deported before their children are processed separately.

“Foster care is not a good option for anyone,” Santana told me, citing woeful outcomes for kids that go through it. But it’s an especially bad option for migrant kids, he said, because they’re entering a place for abused and neglected children even though they themselves haven’t been abused or neglected. “You’re imposing trauma on them unnecessarily,” Santana said.

After years of improvements, the U.S. foster care system is growing again—largely due to parental opioid addiction.www.brookings.edu

After years of improvements, the U.S. foster care system is growing again—largely due to parental opioid addiction.www.brookings.eduFoster care is supposed to be a last resort for children who face danger in their own homes—the number of whom is rising. After hitting a 25-year low in 2012, the number of kids in foster care increased by 10 percent nationwide from 2012 to 2016; in six states, it has increased by more than 50 percent. That’s largely due to the opioid epidemic, Santana said. “We’re now seeing systems with very high case loads, a lack of foster homes to place kids, and a reliance of group homes, which are not the best settings for kids,” he said. “We are especially worried that these influx of kids from the border are going to further tax the system.”

If 10 percent of the 30,000 kids expected to be under HHS care by August end up in the foster system, that’s another 3,000 children—admittedly a blip in a system that already serves nearly 500,000 kids. But Santana worries that the figure could be higher, because many potential sponsors now fear deportation if they come forward to take in a child. The relatives of migrant children are often undocumented themselves, or live with undocumented people. “There have been cases where the Trump administration has gone after sponsors who choose to take care of kids,” Santana said.

But the number of new kids entering the foster care system is not what worries Santana; it’s the amount of resources and effort it will take to heal their unique wounds. “These are going to be kids who need deep trauma services because of the trauma of being separated from their parents,” he said. “Even more challenging for the system is that close to all of these kids don’t speak English, and finding Spanish-speaking resources is very difficult.”

The bill Trump signed in February intends to ease the growing burden on the foster care system by preventing kids from entering it in the first place. As USA Today reported, the new law “puts more money toward at-home parenting classes, mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment—and puts limits on placing children in institutional settings such as group homes.” Santana’s organization supports the bill, because he says ultimately it will reduce the number of kids in foster care and free up space for kids who really need it. But he noted that migrant children separated from their parents won’t likely see the benefits of this new law since most of its provisions don’t take effect until October of 2019 or later.

In April, Trump hailed the law as a way to create “more desirable family atmospheres,” based on the well-founded belief that children always fare best when they’re able to remain with their parents. But since then, he’s made clear that his belief in keeping families intact doesn’t extend to those who are in the most desperate circumstances of all.

No comments :

Post a Comment