By extracting and selling vast amounts of fossil fuels, ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Shell, and ConocoPhillips contributed significantly to climate change—and profited immensely by doing so. Should they now be forced to pay for the damage?

A federal judge said no on Thursday, dismissing a January lawsuit brought by the city of New York, which is particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and extreme weather. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration had argued that the oil giants should help cover the $20 billion cost of constructing levees and sea walls, raising infrastructure, and waterproofing buildings. “Climate change is here and is harming New York City,” the lawsuit said. “This egregious state of affairs is no accident.”

U.S. District Judge John Keenan appeared sympathetic to these claims. In his Thursday opinion, he agreed that the oil companies helped cause global warming—and that they had tried to hide their responsibility. “Despite their early knowledge of climate change risks, Defendants extensively promoted fossil fuels for pervasive use, while denying or downplaying these threats,” Keenan wrote. “Defendants engaged in an overt public relations campaign intended to cast doubt on climate science.”

But Keenan ultimately decided that problems caused by climate change “are not for the judiciary to ameliorate.” Greenhouse gas emissions from the oil companies occur all over the world, not just in New York. Thus, he reasoned, a federal court is not the correct place to decide what companies operating in foreign countries must do.

“To litigate such an action for injuries from foreign greenhouse gas emissions in federal court would severely infringe upon the foreign-policy decisions that are squarely within the purview of the political branches of the U.S. Government,” Keenan wrote. “Global warming and solutions thereto must be addressed by the two other branches of government.”

Keenan’s decision was widely seen as a blow to the growing movement to hold polluters legally accountable for their carbon emissions. As ThinkProgress noted, “The ruling comes less than a month after a judge in California dismissed two similar climate lawsuits from San Francisco and Oakland for the same reason. In both instances, the judges said that climate policies must be set by Congress or the executive branch and not legislated in the courtroom.”

The oil companies involved also hailed the case’s outcome. “Judge Keenan’s decision reaffirms our view that climate change is a complex societal challenge that requires sound governmental policy and is not an issue for the courts,” Shell said in a statement.

But this is not the end for climate liability lawsuits—not even close, said Richard Wiles, executive director of the Center for Climate Integrity. The group supports climate lawsuits seeking to hold polluters financially accountable for their emissions. “New York is an anomaly,” he said. “I don’t think it’s indicative of how the rest of these cases are going end up.”

Wiles thinks these cases—New York, San Francisco, and Oakland—were dismissed because of two solvable failures. One is that they were argued in federal court, when they should have been brought and decided in state and local courts. “These cases are just simply about who’s going to pay for sea walls and other adaptation measures: taxpayers or polluters,” he said. “They’re simple nuisance cases that should be tried in state court.”

Wiles also thinks judges are fundamentally misunderstanding what these cities are asking for—not a widespread political solution to climate change, but monetary damages. “They’re saying the companies created a product they knew would cause a problem, tried to hide that knowledge, continued selling the product, and then the problem occurred,” he said. “They’re not asking the companies to curtail emissions, or stop sales of the product, or even for regulations. They’re saying, pay for our sea-walls.”

In an interview with Grist, Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law agreed that Keenan’s decision doesn’t doom future climate liability lawsuits. “No other court is bound by this decision. It’s as simple as that,” he said. “Each judge and each panel of appellate judges is going to look at these issues independently until it gets resolved by some higher court.”

Until that happens, the lawsuits will keep coming. On Friday, the city of Baltimore filed its own lawsuit against “more than two dozen oil and gas companies that do business in the city, seeking to hold them financially responsible for their contributions to global climate change,” The Baltimore Sun reported. This one was filed in county court.

It’s been a seismic week for American democracy, as the nation confronts the serious possibility that the president of the United States has been compromised by Russia—or at least is being “manipulated,” as Republican Congressman Will Hurd put it in a New York Times op-ed. But President Donald Trump, whom even Fox News castigated, has insisted there’s a good reason for his unusual relationship with Russia: He’s the only thing standing between his critics and war.

“As president, I cannot make decisions on foreign policy in a futile effort to appease partisan critics, or the media, or Democrats who want to do nothing but resist and obstruct,” Trump said Monday in his prepared remarks after the Helsinki summit. “Constructive dialogue between the United States and Russia forwards the opportunity to open new pathways toward peace and stability in our world. I would rather take a political risk in pursuit of peace than to risk peace in pursuit of politics.”

There’s a certain canniness to Trump’s claim, since it’s one of the only ways he could plausibly defend his chumminess with Vladimir Putin, despite evidence that the Russian president had ordered the plot to sway the 2016 election. Trump justified his unorthodox summit last month with North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un in similar terms: as a means to avoid nuclear war, fears of which he had stoked himself. But in Russia’s case, the excuse is even more self-serving. Even the most ardent critics of Russia’s attacks on the American democratic system aren’t seriously proposing military force as a response.

His tweets also betrayed his bad faith. “The Fake News Media wants so badly to see a major confrontation with Russia, even a confrontation that could lead to war,” Trump wrote on Thursday. “They are pushing so recklessly hard and hate the fact that I’ll probably have a good relationship with Putin.” He doubled down a few hours later: “Some people HATE the fact that I got along well with President Putin of Russia,” Trump added. “They would rather go to war than see this. It’s called Trump Derangement Syndrome!”

Trump’s latest excuse for appeasing Putin reveals his unserious, performative approach to the role of commander-in-chief. Though Trump’s predecessors made frequent use of the military in armed conflicts, few if any so lightly invoked the prospect of mass death and destruction. For Trump, war appears to be a largely abstract concept, one he invokes as a political threat without regard for the consequences of doing so.

Trump clearly enjoys being commander-in-chief of the nation’s armed forces. If nothing else, he appears fond of the aesthetics. In the summer of 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron hosted Trump at that year’s Bastille Day festivities in Paris. Trump reportedly returned to the U.S. eager to stage a similar parade in the streets of Washington.

Large-scale reviews of troops, tanks, and other materiel in peacetime are usually more familiar in defunct authoritarian states like East Germany and the Soviet Union. But in France, the annual march down the Champs-Élysées reaffirms the endurance of the country’s revolution and the power of the French Republic, not any one leader. On this side of the Atlantic, the idea is largely unprecedented. American political culture didn’t shed the founders’ fear of standing armies in peacetime until the mid-twentieth century. Open displays of armed might were taboo for most of U.S. history, except to celebrate the end of major wars. The U.S. has achieved no such victory in recent years, but Trump nonetheless touted the parade as a way to honor the nation’s armed forces.

In reality, the parade’s true focus appears to be honoring Trump. His staffers originally asked the Pentagon for tanks, missile launchers, and other military hardware to take part in his inauguration in early 2017. The Pentagon turned down the request, offering the diplomatic excuse that the large tire treads would likely damage the streets in the nation’s capital. Now the military is halfheartedly planning a parade for this fall that would pass muster with the White House and its eager occupant—a stunt that does little but assuage the president’s personal insecurities.

While Trump enjoys playing the role of commander-in-chief, that interest doesn’t appear to translate into exercising any deeper responsibility in the position. His highest-profile exercises of military power have been largely theatrical: a series of missile strikes in Syria that won him praise in D.C.’s foreign-policy circles, followed by the dropping of the largest non-military bomb in the U.S. military’s arsenal in Afghanistan. Neither well-publicized blow actually changed much: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime recently celebrated the capture of the rebel uprising’s birthplace, while the U.S. government is preparing to hold direct talks with the Taliban to end almost two decades of war there.

There’s also evidence that Trump is employing military force more indiscriminately: Watchdog group Airwars estimated that the number of civilians killed in Syria and Iraq by coalition airstrikes rose 200 percent in 2017 over 2016. This comports with the president’s views. “Trump’s words, both in public and private, describe a view that wars should be brutal and swift, waged with overwhelming firepower and, in some cases, with little regard for civilian casualties,” The Washington Post reported in April. On the campaign trail, he vowed to “bomb the shit out of” the Islamic State and to “take out” the families of terrorists.

So it was no surprise when Trump spent the end of last year and the first few months of 2018 engaged in a war of insults with Kim, whose ballistic missile tests unsettled East Asian countries. As tensions ratcheted up with Pyongyang, Trump appeared to view the situation primarily through the lens of his own ego. “North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un just stated that the ‘Nuclear Button is on his desk at all times,’” he tweeted in January. “Will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform him that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!” For a president who campaigned against “dumb” wars, he sure seemed eager to start an even dumber one.

Defensively invoking a potential war with Russia to escape blame fits another habit of Trump’s: framing the nation’s political debate as a polar choice between his views and a catastrophic alternative. If you oppose his plans to ban Muslim travelers from entering the United States, Trump says you bear responsibility for future terrorist attacks. If you criticize his coercive policy of separating asylum-seekers’ children from their parents, you want open borders. If you think U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement should be abolished for its role in that policy, Trump says you’re on the same side as the MS-13 gang.

In fairness, politicians rarely describe their opponents’ views in generous terms. What sets Trump apart is the degree to which he acts first in his own self-interest, with all other concerns coming second. That’s a troubling approach to any of the presidency’s powers and responsibilities. When it comes to war and the potential use of military force, it’s a time bomb waiting to go off.

Donald Trump may not know Margrethe Vestager’s name, but he knows he doesn’t like the European Union’s competition commissioner. At last month’s fractious G-7 meeting in Quebec, Trump told Vestager’s boss, EU Commissioner Jean-Claude Juncker, “Your tax lady, she hates the U.S.”

Asked about Trump’s comment at a press conference on Wednesday in which Vestager handed down a record $5 billion fine against Google—which came just over a year after she fined the company a then-record $2.7 billion—Vestager dismissed it. “I very much like the U.S.,” she said. “But the fact is that this has nothing to do with how I feel. Nothing whatsoever. Just as enforcing competition law, we do it in the world, but we do not do it in political context.”

For Trump, the fine is part of a larger trade war, another sign that the European Union has it out for American companies. But what it actually reflects is a decades-long divergence in the way the U.S. and Europe approach regulation and monopolization. Between the fines levied on Google and the EU’s recent adoption of the European online privacy regulation GDPR, which aims to give consumers control over their personal data, there are signs that the divide could grow.

Does that mean we’re on the verge of the “creation of two Googles or two Amazons,” as Wired suggested? While the different regulatory regimes have created confusion, the real test will be whether the EU does more than levy fines that the big players in Silicon Valley can write off as the cost of doing business.

When Trump defended Google on Thursday morning, he characteristically made the news about himself.

I told you so! The European Union just slapped a Five Billion Dollar fine on one of our great companies, Google. They truly have taken advantage of the U.S., but not for long!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 19, 2018The EU’s decision to slap Google with a $5 billion fine is not about Donald Trump and it certainly has nothing to do with the trade war that the American president kicked off earlier this year. Vestager’s investigation of Google began eight years ago and is still ongoing. While it’s tempting to treat the fine as a “tariff,” as some in the business media have done, that misleadingly suggests it comes in response to Trump’s protectionist push.

What Trump’s tweet does inadvertently reveal, however, is different attitudes towards tech. For Trump, as for his predecessors, Google is a great American corporation. For the European Commission, it’s certainly an American corporation, but its greatness is where the problem lies.

American antitrust law has been guided by one concept: consumer welfare. Pushed by the conservative jurist Robert Bork, whose 1978 Antitrust Paradox is enormously influential, the argument is simple: Economic concentration is only bad if consumers suffer, usually in the form of higher prices. One reason why U.S. regulators haven’t acted against tech giants is that the enormous size of an Amazon, Google, or Facebook hasn’t led to the kind of spike in prices you would expect from companies with monopoly-like powers over the market. Quite the opposite: Google and Facebook are free, while Amazon specializes in slashing prices.

The last big antitrust push from the U.S. government was against Microsoft in the 1990s. Steve Lohr, a New York Times reporter and co-author of the definitive book about the case U.S. v Microsoft, told The Ringer: “If you look at this from an antitrust standpoint, it’s hard to see what you do with Facebook, for example. It’s more a privacy issue. It isn’t the abuse of market power in any kind of traditional sense. The consumer harm is qualitative whereas the traditional measurement [has] always been price.”

The European Union takes a more expansive view. Article 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is devoted to privacy protection, including personal data. While American antitrust law has been dictated by consumer welfare, the EU has been guided by different principles related to privacy and competition between businesses.

President Trump has suggested that the EU “was set up to take advantage of the United States,” which is not true. But the work done to rein in tech companies has made it clear that the EU thinks that large American corporations, particularly Google, are stifling European firms. “Google has used Android as a vehicle to cement the dominance of its search engine,” Vestager said on Wednesday. “These practices have denied rivals the chance to innovate and compete on the merits. They have denied European consumers the benefits of effective competition in the important mobile sphere.”

The argument here is straightforward: Google uses its Android market share, which may be as high as 90 percent, to push its own applications and platforms, leaving out developers working on competing browsers, search engines, and other applications. In the U.S., this isn’t taken as seriously because it doesn’t harm consumers directly—Google’s consumers don’t feel its market share in their pocketbooks. But the EU is making a broader argument, which is that Google is preventing competitors from sprouting up, which has deep economic effects.

It is, of course, important that Google is based in the United States. Vestager and the European Commission are arguing that it is bad for any company to have this kind of power in Europe, but that it is especially bad that that company is not European.

The actual impact of these fines, however, is unclear. Earlier fines against Google and Apple for anticompetitive practices and tax evasion have done little to scare off either company. The latest fine might set a record, but it’s not going to damage Google’s umbrella corporation, Alphabet, which brought in $110 billion in revenue in 2017 and made nearly $7 billion in profit in the final quarter of 2017 alone.

Google is protesting that the ruling could change its business model: Right now the company gives Android to phone manufacturers for free and monetizes it via app bundling and ad targeting. If it were to start licensing it, that could raise costs for manufacturers and ultimately consumers. But so far this seems to be an empty threat.

That doesn’t mean that the increasingly different approaches to antitrust won’t have consequences. As the implementation of GDPR showed, when American companies rushed to meet standards set for European customers, the regulatory divergence creates confusion for both corporations and consumers. As the EU adds regulation and the U.S. sheds them, this trend will only get worse.

But to get companies like Google and Apple to pay attention and to really reform, Vestager will have to aim higher: not just a higher fine, but the threat of trustbusting.

America has federal laws about milk that leave little room for interpretation: The product must be produced in sanitary environments to prevent milk-borne disease. It also must be packaged in hermetically sealed containers, to prevent leaks and spoilage. But what is milk, precisely? That’s not as black and white.

Scott Gottlieb, the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, took a step toward answering that controversial question on Tuesday. Speaking at a policy summit in Washington, D.C., he suggested that no product that doesn’t come from a lactating animal should be allowed to call itself milk. “An almond doesn’t lactate, I must confess,” he said, drawing laughs from the audience.

For nearly two decades, farmers and dairy trade associations have been asking the FDA to ban terms like “soy milk,” “almond milk,” “hemp milk,” and “oat milk”—and if the agency won’t go that far, then to ban those products from the increasingly competitive dairy section. Those terms not only mislead consumers and harm the industry, they argue, but violate the FDA’s legal definition of milk as “the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.”

While previous FDA commissioners were sympathetic to this argument, none were willing to aid the dairy industry’s war against plant-based milks—until Gottlieb. He confirmed on Tuesday that the Trump administration is planning to redefine the labeling rules for milk to be more in line with the dairy industry’s wishes. “[The] FDA plans to solicit public comment on the issue soon before taking further steps,” Politico reported, adding that the process will likely take about a year.

The plant-based milks industry is ready to fight back. “If FDA were to ban the use of dairy terms on plant-based products, we would sue,” said Bruce Friedrich of the non-profit Good Food Institute. Several other groups are prepared to do likewise. At stake, they say, is not just the definition of milk, but the future of commercial free speech.

The feud between dairy producers and alternative milk manufacturers began on February 28, 1997, when the Soyfoods Association of North America asked the FDA to allow the term “soy milk.” The FDA said yes, and in 2000, the National Milk Producers Federation made its own request: That the agency “make clear to manufacturers of imitation dairy products that product names permitted by federal standards of identity, including dairy terms such as ‘milk,’ are to be used only on foods actually made from milk from animals like cows, goats, and sheep.” But the FDA refused to weigh in.

The battle spilled into American living rooms in 2012, when the California Milk Processor Board changed the tone of its iconic “Got Milk?” campaign. Ads that once focused on strong bones and milk mustaches were now about the terrifying prospect of plant-based milk. In one commercial, a mother attempts to comfort her son with a glass of soy milk after he awakens from a nightmare. She shakes the soy milk box so vigorously, she becomes demonic. The boy screams and runs right into a wall. “Real milk needs no shaking,” the narrator says. “Got Milk?”

The ad is meant to be funny, but the industry couldn’t be more serious about the issue. “You haven’t ‘got milk’ if it comes from a seed, nut, or bean,” said Jim Mulhern, the president of the National Milk Producers Federation, said in a statement advocating for FDA action. International Dairy Foods Association president Michael Dykes said that plant-based beverages “do not naturally provide the same level of nutrition to the people buying them as milk does.” Putting a “milk” label on those products “can mislead people into thinking these products are comparable replacements for milk,” he added, “when in fact most are nutritionally inferior.”

It’s true that plant-based milks are not as conventionally nutritious as cow’s milk. Compared to soy, almond, coconut, and rice products, dairy milk is “the most complete and balanced source of protein, fat and carbohydrates” according to a recent study in the Journal of Food Science and Technology described by Time. Per serving, cow’s milk has about 8 grams of protein, 9 grams of fat, and 11.5 grams of carbohydrates, the study said. The most comparable plant alternative is soy milk, which per serving has about 8 grams of protein, 4.5 grams of fat, and 4 grams of carbohydrates.

But nutrition is a complicated, often messy scientific field, and what’s “healthy” depends on individual needs and opinions. Soy milk, for instance, contains more fiber than cow’s milk, and reduces cholesterol instead of increases it. Does that mean it’s less nutritious than cow’s milk, but more healthy? Some pediatricians believe it’s not healthy for children to drink non-human milk; others believe it’s very healthy.

Advocates of alternative milks say these debates, while important, are not relevant to the definition of milk. “As the [FDA] Commissioner noted, the dictionary definition of the word ‘milk’ does include coming from nuts, and this is not a new concept,” the Plant Based Food Association said in an emailed statement. Indeed, Gottlieb on Tuesday acknowledged that “if you open up a dictionary, it talks about milk coming from a lactating animal or a nut.”

This is one of several reasons why non-dairy milk companies reject the idea that they’re misleading consumers. “People understand the difference between dairy milk and plant-based choices,” said Michael Neuwirth, a spokesperson for Silk, which sells a variety of nut-based beverages. “We communicate on our products in a way that avoids confusion between dairy and plant-based.” Some advocates argue that consumers would be misled if non-dairy companies stopped calling their products milk. “No one thinks that almond milk or soy milk comes from cows,” Friedrich of the Good Food Institute said. “There is no consumer confusion, but requiring any sort of change would certainly confuse consumers, who have been buying almond milk and soy milk for decades.”

Friedrich believes that the dairy industry’s accusations wouldn’t hold up before a judge. “Multiple courts have considered the issue of consumer confusion,” he said. “All of them have essentially laughed the concept out of the courtroom.” If customers aren’t being misled, they’re not being harmed.

qz.com

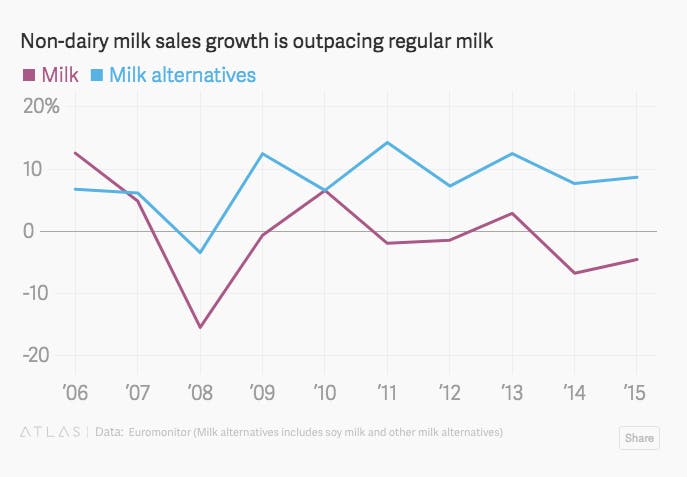

qz.comThe dairy industry, however, has clearly been harmed by the rise of alternative milks. The New York Times reported last year that dairy milk sales fell from $15 billion in 2011 to $12 billion in 2016, partly because “people switched to other beverages, such as soft drinks, fruit juices, bottled water and soy and almond milk.” Plant-based milks “still represent a fraction of the beverage market,” the Times added, but “they are growing in popularity. According to Nielsen, sales of plant-based milks have surged to $1.4 billion from $900 million in 2012.”

The growth of alternative milks thus represent an existential threat to the dairy industry, which is already reeling from President Donald Trump’s trade war with China and Mexico. But Friedrich argues that the industry can’t control trends in consumer choice by changing the name on a label—nor should they, he said, because it violates companies’ First Amendment right to call their products what they want.

“The government is only allowed to restrict commercial speech if there is a substantial risk of consumer harm and their solution is narrowly tailored to solve the harm,” said Friedrich. “As we discussed in our rulemaking petition, there is no way that the act of censoring plant-based milk makers would be able to clear this clear constitutional bar.” Last year, Friedrich’s group filed a petition asking the FDA to explicitly allow plant-based producers to call their products milk, so long as they use qualifiers like “soy” and “almond.”

But Friedrich is optimistic about the alternative milk industry’s chances against dairy producers. The FDA’s Gottlieb is one of the more qualified members of the Trump administration, he said, with a “laudable record of combining an understanding of scientific nuance with common sense practicality.” But if Gottlieb ultimately sides with the dairy industry, then the question becomes: Got a lawyer?

“Real change begins with immediately repealing and replacing the disaster known as Obamacare,” Donald Trump said during one of his final campaign rallies of the 2016 race. “We’re going to repeal it. We’re going to have a really great plan that’s going to cost much less and be much better.” While Trump has kept few of his campaign promises, this one is coming half-true—if not necessarily the way Republicans had planned. Congress failed to repeal the Affordable Care Act, but Trump has attacked the law in subtler, nonetheless devastating ways. For many Americans, Obamacare has effectively ceased to exist.

“Across the country, the details vary but the story is the same. The Trump administration has been rolling back sections of the Obama-era health law piece by piece,” The Wall Street Journal reported on Wednesday. “The result is that the country is increasingly returning to a pre-ACA landscape, where the coverage you get, especially for people without employer-provided insurance, is largely determined by where you live.”

As for a “really great plan that’s going to cost much less,” Trump has been less successful. Last month, he rolled out a rule allowing small businesses to band together to provide cheaper health care to employees—without all of Obamacare’s coverage protections. But on Thursday, Politico reported that the National Federation of Independent Business, a business group that has advocated for so-called association health plans for two decades, won’t be creating such a plan because Trump’s rule is unworkable. Other trade groups are reportedly tepid, too.

In short, the health care system in America, after modest improvements under Obama, is becoming a chaotic mess under Trump—and his political opponents are poised to capitalize on it.

On Thursday morning, 70 Democrats in the House of Representatives launched a Medicare for All caucus. The roll includes a few expected names—Representative Keith Ellison of Minnesota—but also more recent converts to the cause, proving the policy no longer belongs to the fringe. In 2017, 122 House Democrats co-sponsored Representative John Conyers’s Medicare for All bill before he resigned amid a sexual harassment scandal. As Trump’s attacks on the ACA increase, so has Democratic support for a sweeping alternative.

Since Trump took office in 2017, the administration has repealed the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate and expanded access to short-term, limited-duration health plans, which can’t be renewed and offer limited coverage to beneficiaries. Without the individual mandate, SLDI plans can look like sensible, affordable options for consumers—and that means fewer Americans will have health insurance that covers their basic needs. It also influences premiums. As Axios reported in May, ACA premiums have increased by 34 percent since 2017, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates that they’ll increase by another 15 percent next year. Meanwhile, the administration cut spending for ACA outreach. If people don’t know how to enroll in the ACA, they’re less likely to do so at all.

For Republicans concerned about their electoral prospects, Obamacare is no longer such a reliable foe. In 2017, roughly 350,000 Virginians faced the prospect of losing their ACA plans when Optima Health followed the examples of Aetna and Anthem and threatened to pull out of the exchange market. The move would have left nearly half of all Virginia counties without an ACA insurer, with the losses concentrated in Virginia’s western counties—among the poorest in the state. At the time, insurance companies cited market instability for their decisions, and they blamed the Trump administration for causing it. Trump has repeatedly threatened to cut subsidies for the ACA, and insurers worried that would put their profit margins at risk.

Anthem eventually agreed to cover Virginia’s so-called bare counties. But the crisis may have pushed state Republicans away from Trump, at least on the issue of health care. The General Assembly passed Medicaid expansion in 2018. “When you lost all the coal jobs, a lot of people lost their healthcare,” Republican State Representative Terry Kilgore told Belt magazine last month. “People were working but were going to jobs paying $8 to $15 per hour with no healthcare benefits. We need more healthcare options and a healthier workforce.” Kilgore voted for Medicaid expansion.

Medicare for All’s popularity with Democrats can be traced back to Senator Bernie Sanders’s bid for the Democratic nomination in 2016, which brought national attention to the policy. Its appeal has only grown since then, as Democrats have seen how easily a Republican president can weaken the signature achievement of the Obama presidency. Single-payer health care, whether it’s Medicare for All or some other approach, hasn’t proven to be the campaign-killer that some moderates have warned of. Insurgent candidates like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ben Jealous have embraced the policy, and so have some Democrats running in red states.

This opening for Democrats may crack even wider as the material consequences of gutting the ACA become clear. As the Journal reported in March, “Health-insurance premiums are likely to jump right before the November elections, a result of Congress’s omission of federal money to shore up insurance exchanges from its new spending package.” Fearful of the political damage, Republicans are now scrambling to fix the problem. On Thursday, The Hill reported that the GOP House “is planning to vote next week on several GOP-backed health-care measures that supporters say will lower premiums.”

Whether or not Republicans succeed there, they have handed Democrats an opening ahead of the midterms, one that may crack even wider as the material consequences of gutting the ACA become clear. That awakening is already underway, if polling is any indication. Health care topped all issues, even the economy and immigration, in a YouGov/Huffington Post survey in April of registered voters’ priorities ahead of the midterm elections; it consistently ranks in the top three. That’s perhaps less surprising in light of a Navigator Research poll this week that found half of Americans say health care is main cost concern. In an ominous sign for the GOP, independent voters said they trusted Democrats more than Republicans, by an 18-point margin, to bring those costs down.

No comments :

Post a Comment