Starbucks’ recent decision to phase out plastic straws by the year 2020 has come under fire from the disability community. Eliminating straws, they note, has the potential to hurt thousands of people with neurological, movement, and muscular disorders who need plastic straws to safely drink fluids. Starbucks has pointed out that straws won’t actually be eliminated—its stores will still have paper or biodegradable straws available for those who need them. But those alternate straws are often inadequate for disabled people, who need safe, sturdy, flexible straws.

The disability community’s concerns are valid, and have started a necessary conversation about who benefits—and who suffers—from efforts to clean up the ocean. The way some see it, Starbucks is choosing the needs of vulnerable sea turtles over the needs of vulnerable humans. “People like being advocates for the environment and animals. You know why? It’s easy,” one disabled blogger wrote. “Relative to activism and allyship for groups of humans, I mean. The environment doesn’t talk back and tell you that you’re doing it wrong.” At Upworthy, journalist Parker Molloy made a similar observation. “As a society,” she wrote, “we are far too quick to write off the concerns of marginalized groups as insignificant or inconvenient.” As one Twitter user put it, “I choose people over straws.”

But efforts to reduce plastic straws and other single-use products aren’t just about protecting turtles, nor are they solely about preserving some abstract concept of nature. The anti-plastic movement is also about protecting vulnerable humans, who, just like the disabled, rarely have a voice in political discussions.

Of the eight million metric tons of plastic waste that gets lost at sea every year, most break down into tiny microplastics that eventually get ingested by humans via seafood. The health impacts of that are largely unknown—but if scientists do find that it has a negative impact, then developing countries without strong food-safety regulations would be particularly at risk. The plastics that don’t break down, however, tend to swirl in large ocean garbage patches, and eventually wash up on beaches. That becomes particularly problematic when those beaches belong to developing nations that don’t have adequate waste management systems. People wind up burning the plastic trash and inhaling toxic emissions, according to the United Nations.

The U.N. also points out that ocean plastics facilitate the spread of some tropical diseases, “by providing breeding grounds for mosquitos, which can foster the spread of cholera.” Floating plastic, it said, “can survive for thousands of years and can serve as mini transportation devices for invasive species.” The risks and consequences of invasive species and cholera are relatively low in developed countries. But in developing countries, they can be devastating.

Starbucks’ plan to eliminate 1 billion plastic straws per year is not going to solve this problem. China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka are the worst offenders when it comes to ocean plastic pollution, according to a study published in Science. But the United States contributes as well: It was twentieth on that list, “producing as much as 3.5 million metric tons of marine debris each year,” according to The New York Times. In order to reduce that amount of plastic, consumers must push corporations to stop producing so much of it in the first place.

Starbucks’ move to phase out plastic straws is a positive step toward changing a culture that’s accustomed to single-use plastics. At the same time, the company’s plan could cause additional challenges for its disabled customers. Surely Starbucks can find a solution—perhaps keeping plastic straws in a dispenser near the counter, so disabled people can access them without having to ask. In an email, a Starbucks spokesperson would not say if it was reconsidering tweaks to its plan, but said the company “will continue to take an inclusive approach as we look ahead to our phased roll-out.”

The environmental movement has an unfortunate history of ignoring the well-being of humans—particularly marginalized humans—for the sake of animals and “nature.” That’s changed a lot in the last decade, but the movement could still improve how it communicates its priorities. That doesn’t require pitting groups of disadvantaged people against each other; it just requires recognizing that both exist.

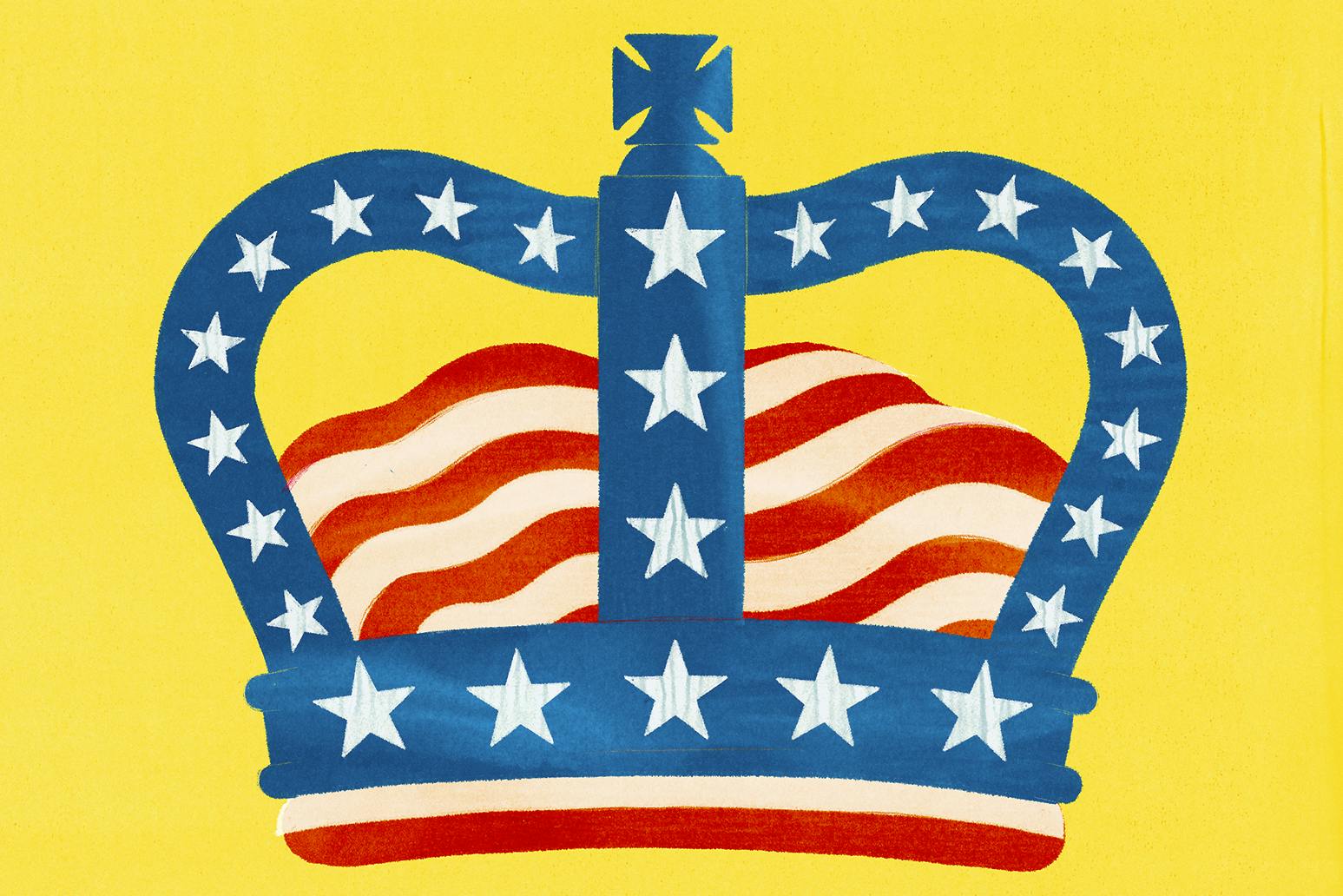

Royalist mania transcends traditional political divisions in the United States. Liberals, who decry entrenched privilege at home, seem strangely OK with a British aristocracy that conveys titles and estates through bloodlines. Fox News talking heads, who denounce coastal “elites” and the Ivy League, nonetheless carried breathless live coverage of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding in May. A 2015 YouGov poll found that Americans, Republicans and Democrats alike, held more favorable opinions of the British queen, Prince William, Prince Harry, and the Duchess of Cambridge than of their own politicians. Even the most popular American politician, Barack Obama, had a favorability that fell below their net rating by a considerable 34 points.

Donald Trump, with his penchant for Versailles-style gilded furniture and his predilection for stamping the family crest on his properties, seems to have a particularly bad case of this national affliction. In April 2017, The Times of London reported that White House staffers had demanded the full Cinderella treatment for his planned state visit: a gold-plated carriage ride to meet the queen at Buckingham Palace. (In order to avoid protests, as well as a giant balloon depicting him as a diapered child, the president will mostly avoid London and instead meet with the prime minister in the countryside, before heading to Windsor Castle for tea with the queen.)

Very little seems to unite Americans these days—except, apparently, their enjoyment in fawning over the rulers the Founding Fathers waged war to overthrow. Once, the United States claimed egalitarianism as a central ideal. What happened?

Americans may believe in meritocracy, but if their obsession with the royal family is any guide, they yearn for a time when fulfillment wasn’t quite so much work.It’s not difficult to see how nostalgia for a system that finds dignity in stasis could take hold. American social mobility, depending on which economist you favor, has either been in steady decline for decades or has at the very least failed to keep up with widening inequality. Today, those born without privilege face daunting barriers to wealth and advancement. And even in the privileged upper class, the scale of competition—plummeting acceptance rates at elite universities, for example—makes it hard to live up to the assumption, hammered into American children from an early age, that they are “special.” Sleep deprivation, which affected 11 percent of Americans in the 1940s, is now a “public health epidemic,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The percentage of people who “worry a lot,” Pew Research analysis shows, has been rising for all income levels since 2003. And prescriptions for both stimulant medications, to keep up in an increasingly chaotic and distracting world, and sedatives, to unwind when it overwhelms, have jumped accordingly.

“This permanent struggle—between the instincts inspired by equality and the means it supplies to satisfy them—harasses and wearies men’s minds,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote of the United States in the early 1800s. Americans may believe in equality and meritocracy, but if their obsession with the royal family is any guide, they yearn for a time when fulfillment wasn’t quite so much work.

The Western world has long seen upticks in nostalgia and reactionism when people are frustrated, fatigued, or frightened. The 1873 financial crisis and resulting depression, for example, shifted politics across Europe and North America: In Vienna, as the Princeton scholar Carl Schorske has written, nationalists with “aristocratic pretensions” seized political control, and intellectuals enthused over the medieval romanticism of Richard Wagner’s operas; in the United States, 1890s populists attacked the banking industry, globalism, and immigrants—and glorified yeoman farmers, pioneers, and the American Revolution. A similar back-to-basics movement flourished in the interwar period, with reactionaries in France, Italy, and Germany scorning bourgeois liberalism in favor of rigid gender roles, healthy diets, open air, and calisthenic routines. (Hitler, inspired in part by the earlier backlash in Vienna, the city of his youth, is only the most famous example.*)

The reactionary sentiment of the past decade seems less like an uptick than a storm surge. The Tea Party, anti-vaxxers, food localism, “paleo” diets, urban astrology, even hipster DIY fermentation (pickles, sauerkraut, and kvass, the alcoholic bread drink first brewed by Slavic peasants in the Middle Ages)—all trends with distinct anti-modern bents—shot up in the years following the financial crisis and the Great Recession, when economic stability, let alone advancement, seemed unattainable to many Americans. (This was also when Donald Trump began venturing seriously into politics.)

/* ARTICLE 148297 */ #article-148860 .article-embed.pull-right { color: #be8d66 !important; text-align: center; } @media (min-width:767px) { #article-148860 .article-embed.pull-right { max-width: 230px; text-align: left; } } #article-148860 .marginalia { line-height: 1.4em; } #article-148860 .marginalia h3 { font-size: 1.1em; line-height: 1.4em; margin-top: 0; } #article-148860 .marginalia h2 { border-top: 6px solid #be8c65; margin: 0; padding-top: .6em; line-height: 1.4em; } #article-148860 .marginalia p { font-family: "Balto", sans-serif; line-height: 1.4em; margin: 0; font-size: 1em; } #article-148860 smaller { font-size: .7em; display: inline-block; line-height: 1.2em; }100,000 bets placed guessing his name (Arthur was the leading contender, at 2:1)

May 19: Royal wedding

Broadcast on 15 U.S. channels (29.2 million viewers)

July 13: Trump’s first official visit to England

80,000 people joined Facebook event to protest his arrival

Sources: The New York Times; Nielsen; Facebook

In 2011, when employment had recovered but wages were still dropping, both Fox News and ABC News aired live coverage of Kate Middleton and Prince William’s April wedding at four o’clock in the morning on a Friday. Earlier that year, audiences had fallen hard for the ancien-régime agitprop of Downton Abbey, which premiered in January. It was unclear which fans responded to more favorably: a dowager countess mowing down meritocrats with one-liners or a romance that involved an earl’s daughter belittling the bourgeoisie as foreplay. A few months later, HBO’s Game of Thrones upped the ante with an ultraviolent drama of “houses” rather than individuals. “It’s the family name that lives on. It’s all that lives on,” patriarch Tywin Lannister said while skinning a stag (a scene that could give Jordan Peterson—the Canadian psychologist and university professor who preaches masculinity from his YouTube channel—a grand mal seizure of joy). That August, The New York Times Magazine published a 5,500-word article on “Decision Fatigue”—the theory that willpower can be depleted by having too many choices in everyday life. Soon, Washingtonian, Harper’s Bazaar, and Bustle all began running stories praising “work uniforms” for the creative class: outfits repeated by choice to free overworked minds for other decisions. Individualism: tiring stuff.

While these examples may seem frivolous, meritocracy fatigue is anything but. At the least, it suggests liberals have something in common with the right-wingers they deplore, and that Trumpism, for its part, is only a symptom of a much broader issue. After all, what did Trump’s supporters vote for in 2016 if not simplicity, a world in which modern problems—inequality, globalization, a changing workplace, and diversifying society—not only had solutions but easy ones, like a literal wall? “Make America Great Again” explicitly invokes a mythical golden age, in which Americans—white, male Americans—didn’t have to deal with the complexity of modern life, their position in the global economy guaranteed as a kind of birthright rather than a matter of market trends.

This premodern craving for a world in which everyone and everything has a place surfaces time and again, in the royal nuptials, in feudal fiction, even in the gilded carriage denied Trump. But however comforting, it’s also a deeply impoverished vision of what life is supposed to be—a pale, passive, unromantic view of humans as chess pieces rather than adventurers in a painful but rich human experience.

The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, writing in 1929, called equality before the law “a psychological state of feeling lord and master of oneself and equal to anybody else.” (He saw dangers in egalitarianism but gave the original idea its due.) This was and remains a radical concept, beautiful and fierce: that whatever a person’s material conditions, they were sovereign over their own life. The challenge now is to find ways to resist royalist escapism and instead to recommit to the radical majesty of the egalitarian project, re-enchanting the everyday.

*Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Hitler was born in Vienna. In fact, he was born in Braunau am Inn, Austria, before moving to Vienna at age 18.

President Donald Trump’s announcement on Monday that he’d nominated Brett Kavanaugh to replace retiring Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy prompted rampant speculation about the future of Roe v. Wade. There was less talk, however, about Massachusetts v. EPA.

The latter ruling, which The Atlantic recently called “the most important court case in U.S. climate law,” is the reason the Environmental Protection Agency has the legal authority to regulate greenhouse gases. The Clean Air Act of 1970 requires the government to regulate air pollution—in fact, the EPA was created to implement those requirements—but in 2003 the Bush administration insisted that the law didn’t compel it to regulate greenhouses gases such as carbon dioxide. Massachusetts and many other states and cities disagreed, and sued.

When the case reached the high court, the justices narrowly ruled that greenhouse gases were indeed pollutants. Kennedy was the deciding vote, joining the court’s four liberal justices. Now, with Kavanaugh set to replace Kennedy, conservatives may have the votes to overturn that precedent.

“Just like the future of Roe v. Wade, the future of federal action to rein in climate change should be a huge issue in [Kavanaugh’s] confirmation hearing,” said Abbie Dillen, the vice president of climate litigation at Earthjustice.

Kavanaugh, a 53-year-old judge for the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, is “pretty consistently anti-environment on every front,” Center for Biological Diversity senior counsel Bill Snape told BuzzFeed News. That includes the issue of greenhouse gases. Kavanaugh “will not be afraid to say that greenhouse gases don’t fall into the category of pollutants the [Clean Air Act] was supposed to address,” said Brendan Collins, an environmental litigator at Ballard Spahr LLP who has argued before Kavanaugh. “He maintains a level of discomfort of anything he regards as a reach, authority-wise, from the EPA.”

In a 2012 case, for instance, Kavanaugh rejected the EPA’s authority to create a greenhouse gas permitting program. “The task of dealing with global warming is urgent and important,” he wrote. But, he added, “As a court it is not our job to make policy choices.”

Overturning Massachusetts v. EPA has long been a dream of conservatives because the decision was the impetus for the EPA’s 2009 rule—known as “the endangerment finding”—stating that climate change is hazardous to human health and must be regulated. That rule is the main reason the Trump administration can’t simply eliminate every climate regulation President Barack Obama put in place during his tenure. Overturning Massachusetts v. EPA would thus make it easier for Trump’s EPA to do away with the endangerment finding, and create a glide path for gutting air pollution regulations. That prospect “could not be more alarming,” Dillen said. “We need every possible tool to address climate change. We’re running out of time.”

The elimination of the endangerment finding has long been considered improbable, if not impossible, given the makeup of the Supreme Court, the existing legal precedent of Massachusetts v. EPA, and the reluctance of the EPA administrator to challenge it. Two of those realities, however, have now changed. Not only is Kennedy gone, but coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler has replaced Scott Pruitt as head of the EPA.

Wheeler did say last week that he considers Massachusetts v. EPA settled law: “There would have to be a major, compelling reason to try to ever reopen that.” But he’s been critical of the decision in the past, and some say he could be more effective than Pruitt if he did decide to repeal the endangerment finding. “The difference may lie in Wheeler’s long experience in Washington, D.C.,” Dillen said. “He may have a more focused attention to coal issues since he’s been a coal lobbyist for much of his career.”

Vermont Law School professor Patrick Parenteau is less convinced that anything has changed. “I don’t think [Massachusetts v. EPA] is in any jeopardy,” he said, adding that Chief Justice John Roberts has previously said he doesn’t feel it’s necessary to revisit the decision. “They just don’t seem to have the appetite for that. Even Wheeler—everything I’ve seen has indicated that they’re reluctant to take that on.” Collins, too, expressed skepticism. “There’s always a tendency to overstate the degree to which people are interested in tearing up established law,” he said. “There’s a strong tendency, frankly, under the Roberts Court to leave in place established case law unless there is some clear call to make a change.”

Even if Massachusetts v. EPA itself isn’t at risk, however, Kavanaugh’s confirmation could lead the Supreme Court to weaken the EPA’s authority to create aggressive climate regulations under the Clean Air Act. Trump’s EPA is expected soon to release a weaker version of the Clean Power Plan, Obama’s signature regulation to fight global warming, and it “will inevitably take a very narrow view of EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act,” Dillen said. The new rule is also certain to get challenged in court, eventually giving the Supreme Court an opportunity to rule on the Trump EPA’s more narrow interpretation.

It’s frustrating to environmentalists that such important decisions often lie with a group of nine men and women. But the Supreme Court’s power on environmental issues stems from Congress’ repeated refusal to pass legislation giving the government clear authority to fight climate change. Now, the future of greenhouse gas regulation is in the hands of Chief Justice Roberts, who could well change his mind about revisiting Massachusetts v. EPA. If that happens, Parenteau noted, “five votes is all it takes.” And Kavanaugh would surely be one of them.

This week Netflix premiered its first original series made in India, a cop thriller called Sacred Games. Adapted from the enormous 2006 novel by Vikram Chandra, Sacred Games is a sophisticated move in Netflix’s quest to net every eyeball on earth. Netflix India launched three years ago, but has struggled to compete with Amazon Video and Indian properties like Hotstar and Flipkart. Netflix is also pushing the show heavily in the U.S. and Europe, so Sacred Games is doing double duty for them: proving to the huge Indian market that the network is invested in quality content for and about India, while also diversifying its content for the markets it currently dominates. Netflix already offers English-speaking viewers a very strong portfolio of high quality foreign-language detective shows, so this Chandra adaptation feels like an obvious choice.

It must also have been an expensive one. Sacred Games is awash in gunfights, dreamily gorgeous production, and tricky overhead shots. The bones of its plot are simple. Sartaj Singh (Saif Ali Khan) is a Mumbai cop down on his luck; his wife has left, he hasn’t solved any good cases. Then one day he gets a phone call from a man who says that he feels like a god. Is this a tip, or is this guy crazy? It might be both. The caller promises that in 25 days a great disaster will visit Mumbai, and everybody will die. The caller turns out to be notorious gangster Ganesh Gaitonde (Nawazuddin Siddiqui). The show plays out in a race-against-time format, as Singh battles his corrupt department to chase the clues Gaitonde has left him.

Straightforward though this premise may be, Sacred Games is a labyrinthine show. Gaitonde’s calls to Singh transform into a voiceover that speaks over every episode in the series. His biography becomes a second core to Sacred Games, competing with the crime mystery itself. His voice is like a narrative voice in a literary sense; a disembodied stream of memory, coloring the world and giving it stakes. Gaitonde narrates his life from his childhood as the son of a poor monk to mob boss of Mumbai’s Gopalmath district. His delusions of godliness began early, growing and twisting through encounters with a leopard; brutal violence; intense love.

Though Gaitonde sees himself as a god, it’s in the satirical sense of a nonbeliever. “My name is Ganesh Gaitonde,” he bellows as he takes control of his ghetto from his gangster rivals. “I don’t trust anyone.” He is the one true god of Gopalmath, he declares, because he runs this town. Religion is a turbulent seam in Sacred Games. Gaitonde assembles a diverse gang of ruffians, initially refusing to engage in anti-Muslim violence in the region he controls. But the real money, he eventually realizes, is in politics, and that means election-rigging, and that means suppressing Muslim votes. Later, a personal loss ignites a sense of ethnic consciousness in him that had never stirred before: A woman’s death “awoke the Hindu in me,” Gaitonde says. He kills hundreds of Muslims, innocent and guilty alike. But she never comes back to life.

It is fortunate that Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Saif Ali Khan rarely act across from one another. Singh is a solid, attractive protagonist, and we root for him continually. At one point he very seriously consults his mother for help in his case. But Siddiqui is an actor of rare magnetism. It’s hard to locate where that charisma lies: He does not wander very much from a hard-set expression of cruel determination. But I could watch Siddiqui set his brows into that furrow all day. The faintly mystical aura of his biography and certain strange wanderings into romantic love do not so much humanize Gaitonde as make him more marvelous, more mysterious.

Of his love interests, Kukoo (Kubra Sait) is the most interesting. She is a gangland nightclub dancer, dripping in glamour. Gaitonde wins Kukoo from Suleiman Isa, his rival, after being captivated by her “magic.” She becomes his gangster’s moll and a lucky charm. After being lovers for a while, Kukoo tearfully reveals to Gaitonde that she is transgender. It’s a shame that she does not last long in the show after that. It’s also strange that she is the only character to receive the full-frontal nudity treatment in the entire show. On the one hand, their relationship feels real, loving, worth preserving. On the other, Kukoo is fetishized by the show, with Sacred Games declining to bless her with either long life or longstanding significance.

The show features several other standout performances by women. Besides Kukoo, there is Anjali Mathur (Radhika Apte), an agent from RAW, India’s intelligence service. She’s young, beautiful, dominant, and ruthless. Her character motivation is a little reductive, driven as she is to outshine men in the field, but Apte’s performance is cleverer than that. Equally ruthless but in a very different style is Kanta Bai (Shalini Vatsa), the brains behind Gaitonde’s operations. Without its women, Sacred Games would play out like a pissing contest between two men, one who loves crime and another who hates it.

Sacred Games is a show that runs on a number of overlapping dynamics. We have Singh and Gaitonde, locked in a dyad. We have Gaitonde as a lone, deranged mind, separate from and abusing the world around him. We have the individual crimes of one gang, and we have the long-churning turbulence of religious unrest in overpopulated Mumbai. The social bumps up against the psychological; personal enmity meets political tectonics.

The many streams of Sacred Games makes it, to be honest, confusing viewing. I lost track of the year we were in and the crime Singh was investigating. But though I lost my bearings in the sweep of the series’ action, I never lost my attention. Despite small elements of hamminess—some unnecessary slo-mo, some bad guitar solo in the soundtrack—Sacred Games remains throughout its eight episodes a highly distinctive cop procedural. The very expansiveness of its concerns, which incorporate the mystical-religious, set it so far apart from the customary scandi-noir that the genre feels begun anew. For Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s face alone I would watch it again.

No comments :

Post a Comment