“It’s not rape if it’s your wife, am I right?” Erran Morad says. He laughs and extends his hand to Larry Pratt, executive director emeritus of Gun Owners of America, who shakes it. Morad has a rhomboid jaw and walks like he has razorblades in his armpits. But this Israeli gun rights advocate is in fact one of four characters played by British prankster Sacha Baron Cohen in his new Showtime series Who Is America?

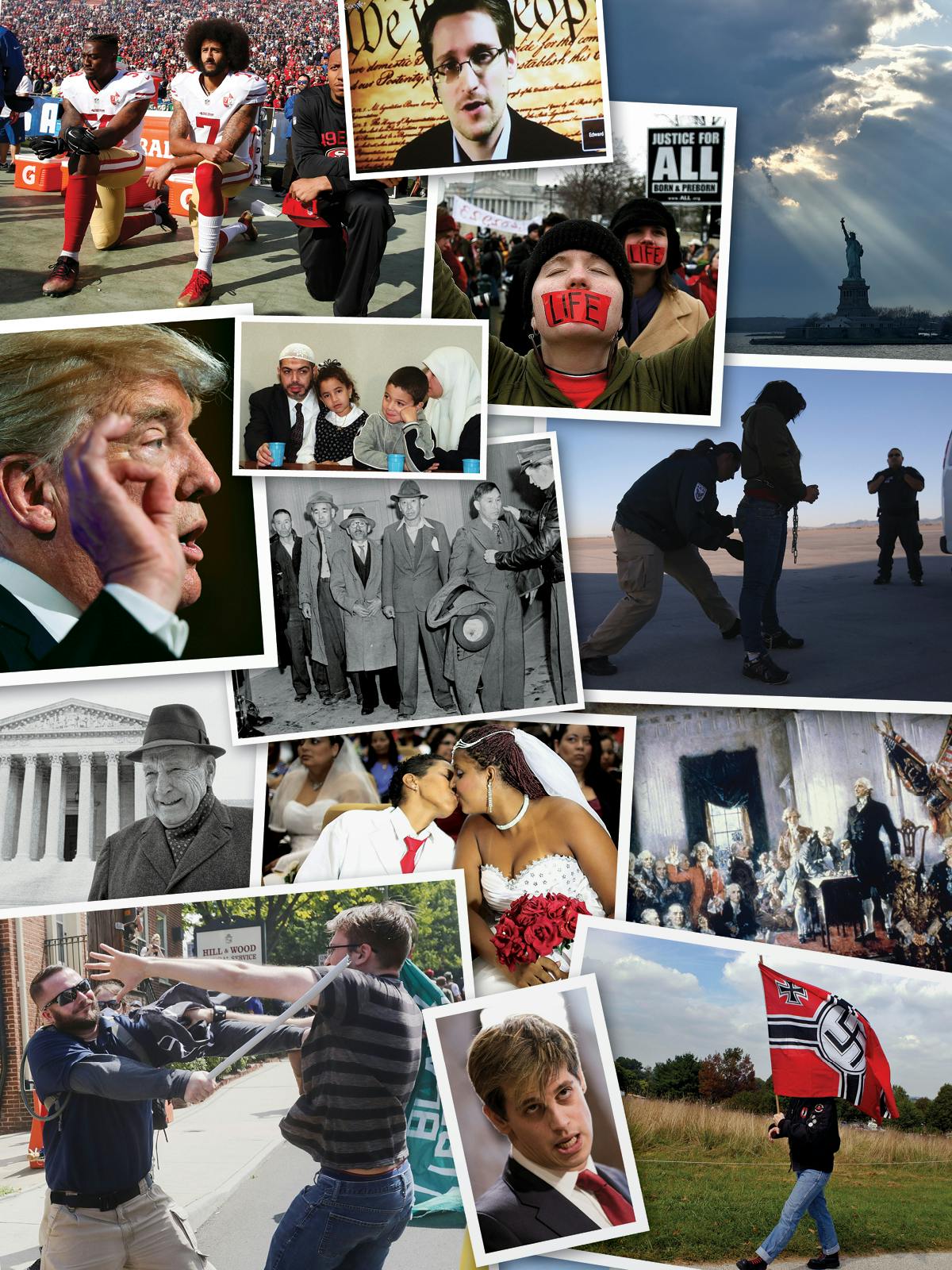

The debut episode, which aired on Sunday, opens with a montage of scenes that have defined the country: the moon landing, JFK asking what you can do for your country, and so on. Then it snaps to Donald Trump mocking reporter Serge Kovaleski’s disability in 2015, as if in answer to the title’s question. The four Sacha Baron Cohen roles pick it up from there: Morad, alt-right broadcaster Dr. Billy Wayne Ruddick Jr., PhD, lefty pink pussy hat-wearer Dr. Nira Cain-N’Degeocello, and ex-con artist Rick Sherman (“I made one mistake, just fourteen times”). Each of these characters is supposed to extract some observational truth about American culture, I think, with the overall effect of showing how fragmented and post-reality the country feels today.

Morad produces the most jaw-dropping spectacle of the show, and the one with the clearest payoff. On a pitch tour of American Republicans, he convinces a number of current and former members of Congress and other prominent conservatives to agree with him that preschoolers should be armed with guns. He gets Philip van Cleave of the Virginia Citizens Defense League to appear in a training video for toddlers. “Today we are gonna teach you how you can stop these naughty men and have them take a long nap,” he says. Former Senate majority leader Trent Lott, congressmen Dana Rohrabacher and Joe Wilson, and former congressman Joe Walsh all follow suit, agreeing that certain “highly trained” children ought to be carrying guns in school. “In less than a month they can go from first grader to first grenader!” Joe Walsh exclaims. “The great thing about toddlers is that they have no fear of guns,” Morad observes, to sage nods. Pratt, of Gun Owners of America, continues the theme: “Toddlers are pure, uncorrupted by fake news and homosexuality.”

It is shocking viewing, but there’s also the sense that one shouldn’t be surprised. The unthinkable happens every day in contemporary politics. The day after this show premiered, Trump stood next to Vladimir Putin at a press conference and essentially sided with the Russian leader over the U.S. intelligence community. Cohen’s feat in the Morad character, then, is to push the political surreal into the uncanny, by bringing children’s television into it. He got Van Cleave to sing a song about aiming your gun at the “head, shoulders—not the toes, not the toes.” It’s ghoulish. If we are becoming numb to the dreamlike in our political theater, we at least are not yet immune to the eldritch specter of kids with fluffy firearms.

A friend of mine, also British, compared Cohen’s style with that of Louis Theroux, the other famous English interviewer. The self-deprecating and innocent Theroux brings out his subjects by creating a void where they expect the interviewer’s ego to be. He doesn’t play a character, he just plays a very nonjudgmental and kind version of himself.

But where Theroux makes space for the subject’s hubris or delusion to dominate the screen, Cohen does the opposite. In each of these characters, Cohen pushes rather than pulls. He pushes them to agree or disagree or to otherwise react to his insane statements, to see what people will do when they are knocked off the kilter of ordinary human interaction.

The value of this technique varies pretty widely. In the Morad segment, Cohen gets various Republicans to unmask parts of themselves. But in the other three segments, he only seems out to entertain. Who is America? begins with an interview between Cohen (as Ruddick, a fringe conservative broadcaster) and Senator Bernie Sanders. The scene is a bravura performance from Cohen, who gives an incredible account of how Sanders could transfer the 99 percent into the 1 percent, thus solving inequality. Sanders says he has no idea what Billy is talking about. I suppose it goes to show that Sanders is sane.

Also sane-appearing are the Republican couple who host Cain-N’Degeocello, the supposed Reed lecturer, and the Laguna Beach gallerist who humors Nick Sherman, recently released from prison. In the first scene, Cohen plays a performative liberal who bikes around in a pussy hat trying to “heal the divide” between himself and Republicans. The performance is a little bit offensive, as when Cain-N’Degeocello performs a fake Native American chant instead of grace. It’s partly brilliant, as when the character explains that when he forces his daughter to free-bleed he puts down a cloth because “it protects the Herman Miller chairs, which we love.” Throughout the dinner his Republican hosts seem perplexed and not much else.

When confronted by a lisping artist who has been incarcerated for 21 years, and who then shows her the art he has made with his feces, the Laguna Beach gallerist is positively heroic. She is kind about Sherman’s art, presents a pretty serious reading of its intentions, and supports his vision. What is the joke supposed to be here? That you can make art out of literal shit and get called a genius for it? If that was the intention, I don’t see why Cohen chose some provincial gallerist who peddles landscapes rather than a serious art-world gatekeeper. The whole segment was baffling—a medium-funny concept, but with no discernible target, political or otherwise.

The most fun moment in the first episode of Who Is America? must be the scene where Pratt, reciting a script given to him by Cohen (as Morad), explains how four year-olds see things “essentially, like owls ... in slow motion” and have “elevated levels of the hormone blink 182, produced by the part of the liver known as the Rita Ora. This allows nerve reflexes to travel along the Cardi B neural pathway to the Wiz Khalifa 40 times faster.” This is a low-level gag, but it’s so funny that it actually cheers you up a bit by forcibly dragging some humor out of the trainwreck of our public discourse.

This joke, as well as this whole segment on child gun rights, has a close ancestor in Chris Brown’s classic parody show Brass Eye. In that show’s special on the public hysteria about pedophiles, Brown got a popular British radio host called Neil Fox to claim that, “Genetically, pedophiles have more genes in common with crabs than they do with you and me. Now that is scientific fact. There’s no real evidence for it, but it is scientific fact.”

Being cheered up by a public figure acting like a complete idiot has some political value, because it helps you feel like somebody is on your side. But, as with Brass Eye, What Is America? reaches out across the screen and says to the viewer that not only does Cohen see what we see in American politics, he sees how maddened we are by the carousel of political television. When Neil Fox proclaimed that crabs and pedophiles were close cousins, and when Larry Pratt explains the operation of the Cardi B neural pathway, a wrench is thrown into the usual machinery of television that lurches from producer, through script, talent, banal statement, viewer outrage, brief news cycle, then back to the start.

Maryam Nawaz Sharif wore Gucci slippers to prison. They were white flats and cost about 65,000 Pakistani rupees, an exorbitant sum. They were a striking choice for someone headed to a sentence for graft—assisting in the emptying out of the Pakistan’s nearly empty coffers into the Sharifs’ rather full ones. It could have been an unthinking selection, a final hats-off to style before the surrender, but more likely it was a symbol of defiance, a deft calculation by an icon in the making.

On the afternoon of July 13, 2018, the prim daughter of thrice-deposed Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, shod in her Gucci slippers, boarded a plane from Abu Dhabi to Lahore in Pakistan. Just a week earlier, a court in Pakistan convicted her father on the vague charge of owning assets beyond his known income. It also found Maryam guilty of abetting his crime, having been “instrumental” in the subterfuge that permitted her father to hide his misbegotten assets. Clearly she had taken being the dutiful daughter a bit too far; she was sentenced to a eight years in prison.

The father and daughter were at the time of the verdict in London, in the very Park Lane property that they had allegedly procured via their graft. Avenfield House is a stately place, albeit a bit less so in recent days with the ruckus of protestors who had gathered outside following the verdict. The family had gathered at the sickbed of Kulsoom Nawaz, Maryam’s mother, who had slipped into a coma following treatment for throat cancer. She reportedly opened her eyes once when they came to bid her goodbye.

The fate of women running for political office is tricky in the unruly moment in which the world finds itself. America is still reeling from its own struggle of disentangling misogyny from political liability, deciding which parts of which affected the fate of Hillary Clinton. It is still impossible to tell how many refused to vote for her just because she is a woman and how many because they were concerned about the accusations against her. The protestors outside Avenfield House may not have been chanting “Lock Her Up,” but some of their accusations were similar, as were the charges. She had been corrupt, she didn’t care about common people, she was disconnected from the lives of real Pakistanis—these have long being thrown around as reasons to oppose Maryam Nawaz. Since July 6, when the verdict was announced, a new one was added: she would never leave London, she would never come home to go to jail.

She did return. Etihad Airlines flight 243, the plane carrying the duo, entered Pakistani airspace sometime after 8:00 pm Pakistan time on July 18, 2018. Cell phone service and even internet service in Lahore had been suspended for its arrival, and Section 144, a legal provision that permits the Government to suspend the right of assembly, had been deployed in the area around the airport.

Pakistani news channels and their anchors reported the flight’s arrival with glee, emphasizing that its passengers were now subject to Pakistani law; there was no chance now for Maryam and her father to escape being locked up. When the plane did land it was escorted to a separate area away from the terminal and jet bridges of usual arrivals. All the passengers of the flight were vacated and then, finally, Maryam Nawaz Sharif emerged, looking un-harried and un-worried as she descended the staircase into a sea of men waiting to arrest her.

Maryam Nawaz seems sharply aware of the political dividends of a wrongful conviction narrative, her allotted prisoner number, the difficult conditions—all elements of the stagecraft of her suffering.Maryam Nawaz has been fighting long before this moment, arguing that the charges are trumped up. The twists and turns in the nine-month trial included a finding of no wrongdoing by the Supreme Court, before the case was shunted to a lower “accountability” court which handed out the most recent verdict. While the military does not have any visible involvement, the Sharif family’s tense relationship with them has led some to wonder whether the verdict had military backing. Instead of treading carefully, Maryam Nawaz has been pressing her father and uncle to take a harder line against the Pakistani military, which she believes is behind even the Avenfield verdict (whose name comes from the court’s investigation into how the Sharifs funded their purchase of Avenfield House). Some of the opposition to doing this comes from within her family and those who stand to benefit from the imprisonment of both of the two top leaders of their party, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz). One of them is Maryam’s uncle, Shahbaz Sharif, long-time Chief Minister of Punjab, the country’s largest province. Following the indictments of brother and niece, he has continued campaigning, refusing to directly confront the military or push the allegation of a doctored verdict. While Maryam and her father are questioning the legitimacy of the July 25 election, in which they, the frontrunners, are disqualified, he seems ready to accept the results, particularly if they install him as the top man in Pakistan.

For a woman running for top office in Pakistan, even the internecine fighting and contrived corruption cases are not the sum of suffering. Pakistan’s religious extremists, steadfastly opposed to women in office, seem to be regaining force, some of them having been inexplicably removed from the suspected terrorist watch-lists, which required them to be under constant observation. They add to new groups, like the Islamic State, that are eager to set up shop in the country. On the day Maryam Nawaz returned to Pakistan, a devastating suicide blast in Mastung, in Balochistan province, targeted a political meeting being held by the secular Balochistan National Party, killing 128 people and injuring 200. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in the country since the 2014 attack on Army Public School in Peshawar.

All of it is chilling, particularly given that Pakistan’s last female Prime Minister was killed in a suicide blast while attending a political rally. It is not daunting enough to stop Maryam Nawaz, who seems ever aware of the theatric worth of political spectacle. A frequent tweeter, she shared pictures of the tearful goodbyes she had said to her children prior to leaving for Pakistan, sagely tweeting “I told my kids to be brave in the face of oppression. But kids will still be kids. Goodbyes are hard, even for the grownups.” She has been sending missives even from jail, one of them a letter written in English and posted on her Facebook account. In it, Maryam declares that she is refusing the special “B” class privileges afforded to Pakistan’s wealthy prisoners, choosing instead to be housed like a regular inmate in Adiala Prison. Her father, housed in a cell where another arrested Prime Minister once stayed, has not been so stoic. He has been complaining about the “facilities,” the dirty bathroom, the absence of an air-conditioner in the punishing 100-degree-plus heat.

Clad in Gucci slippers as she may have been, Maryam Nawaz seems sharply aware of the political dividends of a wrongful conviction narrative, her allotted prisoner number, the difficult conditions—all elements of the stagecraft of her suffering. There are a few solid legal reasons that the verdict and her sentencing are problematic. In his decision, Judge Muhammad Basheer flouted precedent by relying on testimony that under settled precedent should not have been admitted. He did not provide a legal rationale for doing so. In the words of one legal expert, the whole decision in the Avenfield case is “utterly devoid of legal reasoning,” relying on a non-binding report to reach its conclusions. Appeals are expected to be filed early next week.

If confronted, Pakistanis, like many Americans, will claim never to vote based on gender. But the truth is far from that and the tiny number of women in political office in Pakistan is evidence. If there is anything that can eliminate the political burdens of being a woman, it is the empathy borne of what viewers perceive as unjustly imposed suffering. Unlike powerful women, suffering women are palatable, even popular, in Pakistan; they are the stars of soaps and the winners of hearts. With the reality-tv drama of her arrest, the slippers she wore and then the suddenly deplorable details of her confinement, Maryam Nawaz has entered the ranks of those women. She went in as a political daughter propped up by the power of her father; she may well emerge an independently powerful, and deeply complicated, national heroine.

Last March, Anthony Romero, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, stepped onstage for a “resistance training” event with 2,000 volunteers packed into an arena at the University of Miami. It had been seven weeks since Donald Trump took office. Now, Romero said, it was time for the volunteers to join the group in fighting the Trump administration’s crackdown on civil liberties. “Let’s do it together,” he said, to cheers from the crowd. “We need you to be protagonists in the struggle.”

The event, which was live-streamed to more than 200,000 people watching at gatherings around the country, was unlike anything the ACLU had ever done in its 97-year history. Founded after World War I in reaction to government raids targeting immigrants, union organizers, and left-wing activists, the ACLU has served as the nation’s foremost champion of civil liberties for almost a century. It has been involved in some of the most important and controversial legal cases in U.S. history, cultivating a reputation as a nonpartisan organization that confronts the government on a principled basis, regardless of which political party is in power.

Since the 2016 election, the ACLU has entered a new and unprecedented phase, becoming one of the most active groups confronting Donald Trump. In the days after the election, when millions of Americans were still reeling from Trump’s surprise victory, the group took out a full-page ad in The New York Times informing the incoming president that “you will have to contend with the full firepower of the ACLU at your every step.” On Twitter, it issued a stark warning: If Trump moved to implement his unconstitutional campaign promises, it declared, “We’ll see him in court.” A week after his inauguration, when Trump attempted to ban immigrants and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries from coming into the United States, ACLU lawyers rushed to secure an emergency injunction and fanned out to airports across the country to provide legal assistance to those denied entry. Outside the Brooklyn courthouse where they won the first victory against the ban, the ACLU’s lawyers were greeted as heroes. Over the next few days, the organization received a staggering $24 million in donations.

Public enthusiasm for the ACLU has only continued to grow. Since Trump’s election, the organization’s ranks have swelled from 450,000 members to more than 1.8 million, more than at any time in its history. Flush with cash, the ACLU is continuing to challenge the Trump administration and like-minded state governments, filing more than 100 lawsuits against attempts to restrict immigration and ban transgender individuals from serving in the military, among other issues. The group has been central in fighting the administration’s crackdown at the border, winning an injunction to halt the separation of immigrant families under Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy. It is in the midst of hiring nearly 100 new employees to supplement its 436 staffers.

Along with these conventional measures, the group is now taking the unusual step of using its members to fight Trump’s agenda directly. That day in Florida, the ACLU launched a $5 million grassroots organizing campaign called People Power. Its goal is to harness the energy of the opposition to Trump and employ it to force politicians to take action on a range of issues, from protecting undocumented immigrants to expanding voting rights. “We’ll do the work in the courts, you do the work in the streets,” Romero told the crowd at the University of Miami. “Failure is not an option.”

In an even more unprecedented push into electoral politics, this fall the ACLU also plans to spend $25 million on advertisements and other forms of voter outreach to support its agenda. And the group is borrowing a pressure tactic from an unlikely source: the National Rifle Association. The ACLU has been issuing scorecard ratings to candidates based on their track records of protecting civil liberties, much like the NRA’s system to compel right-wing legislators to hold the line on gun control. The ACLU’s targets will include Kris Kobach, the Kansas secretary of state, and Joe Arpaio, the Arizona sheriff turned Senate candidate whom the organization previously fought in court.

Because of its long-standing commitment to nonpartisanship, and because it is a nonprofit, the ACLU won’t be setting up a political action committee or endorsing particular candidates. But its leanings won’t be hard to figure out. “In the races we engage in, the distinctions will be obvious, they’ll be stark,” said Ronald Newman, the ACLU’s director of strategic initiatives, who before joining the ACLU worked in the Obama administration. “Folks will know which side of the coin we’re on.”

It’s a noteworthy strategy, one that marks a new chapter in the ACLU’s approach to protecting civil rights. By enlisting the wave of activists galvanized by Trump’s election and policies, the group hopes to expand its influence beyond the courts and into state houses, governor’s mansions, and the halls of Congress. At a moment when a wide range of constitutional rights seem to be under assault, the ACLU’s new posture is a signal to its members that it won’t simply respond with a lawsuit or an amicus brief. Just as the NRA has helped elect politicians who hold the Second Amendment sacrosanct, the ACLU wants to reassert civil liberties as the bedrock principles on which the United States was founded—and to make politicians think twice before enacting policies that endanger those rights, lest they face the wrath of a large and motivated group of activists.

The ACLU’s new approach raises important questions about what its continuing role in American society should be. Can a group defined by principled opposition to threats to civil liberties lead a popular movement? Can the ACLU engage in grassroots activism and still stick to its traditionally nonpartisan approach? Or do its principles need to be adapted to today’s political realities? At a time when liberals and conservatives are locked in a bitter debate over where the real danger to free speech lies, is it still possible to have an organization that fights for the full spectrum of civil liberties—for all Americans?

The question of whether to defend modern-day hate groups like Vanguard America, which rallied at the Lincoln Memorial last June, has sparked a debate about the ACLU’s traditional approach. Mark Peterson/Redux

The question of whether to defend modern-day hate groups like Vanguard America, which rallied at the Lincoln Memorial last June, has sparked a debate about the ACLU’s traditional approach. Mark Peterson/ReduxIn July 2016, the ACLU released a report that tried to imagine America under a Trump administration. The document analyzed the range of threats he had made to Muslims and immigrants and his praise for torture and surveillance. His policies, the group warned, would “trigger a constitutional crisis,” and the ACLU wanted to be ready to respond. Still, election night took the organization, like so many millions of Americans, by surprise. David Cole, the ACLU’s new legal director, told me he signed on for the job in the summer of 2016 with the notion that Hillary Clinton would win the presidency and appoint Justice Antonin Scalia’s successor to the Supreme Court, resulting in the first real liberal majority on the Court since the Nixon era. A liberal Court would mean the ACLU could spend less time countering attacks on civil liberties and more on expanding those rights through the courts. With Trump in the White House, those hopes essentially disappeared.

Even before the election, though, the organization had been thinking about how it might increase its reach. Public support for the ACLU tends to fall off during Democratic presidencies, when erstwhile backers forget that there are still civil liberties fights worth having. During the Obama years, the NRA was significantly outfund-raising the ACLU: In 2012, most of the gun rights group’s $256 million in revenue came from membership fees and annual dues; the ACLU’s was less than half of that. The NRA also had a huge grassroots following that it leveraged into political clout.

Romero believed that studying the NRA’s methods could help the ACLU become a more powerful advocate for civil liberties. In 2013, he commissioned an outside firm, Douglas Gould and Company, to analyze the NRA’s structure and tactics. The resulting 50-page report highlighted the ways in which the NRA had inserted itself into the cultural zeitgeist: stoking fears of criminals, minorities, and a liberal president coming to take people’s firearms away; engaging in special outreach efforts aimed at women and young adults; and partnering with corporate affiliates to offer member discounts. In short, the NRA had made itself powerful by linking membership to a particular kind of world view.

“There’s a lot we learned from the NRA,” Anthony Romero said. “If we could be a little less legalistic, we thought we would have a bigger impact.”The report concluded that while the ACLU’s broad agenda—compared to the NRA’s lockstep fidelity to a single mission—made it harder to galvanize supporters, there were things it could do to raise its profile: score candidates on their records; engage in voter registration efforts; increase its lobbying; and do a better job of connecting with its members, through live events and online organizing campaigns. “There’s a lot we learned from the NRA,” Romero said. “If we could be a little less legalistic and focus less on the brain and more on the heart and trying to change the culture, we thought we would have a bigger impact.”

It was a provocative reimagining of the ACLU. For nearly a century, the organization has mostly stayed out of electoral politics, and its position as an unbiased actor has been a critical part of its identity and its track record of success. It was a tradition in keeping with many other special interest groups in Washington; working with activists and lawmakers from both political parties was considered the best way to build support for a cause. Even the NRA contributed significantly to Democratic congressional campaigns until a sharp decrease in the early 1990s. The Republican Revolution, however, ushered in a more combative style of politics, and since then, polarization has spiked dramatically. Today, according to the Pew Research Center, the ideological gap between Democrats and Republicans is larger than at any point since the group started tracking the issue in 1994.

It’s a difficult environment for political organizations that try to work with both sides. Many of the most successful advocacy groups don’t try to bridge the divide; instead, they encourage and exploit it. Since 1994, for example, when Democrats in Congress passed a ten-year ban on assault weapons, the NRA has increasingly favored the GOP and gone after Democrats. There’s no confusion about where today’s NRA stands on the ideological spectrum.

Even as the ACLU prepares to engage in electoral efforts this fall, it continues to promise that it will maintain its nonpartisan stance. But the reality is that the issues around which it hopes to organize its followers—racial justice, immigration rights, reproductive rights, and more—are ones that mainly motivate liberals to fight against conservatives. It’s impossible to disentangle these battles from their larger political contexts. And the ACLU’s shift into political activism is at the very least a tacit acknowledgment that to be effective in today’s polarized environment, it cannot remain above the fray.

Romero didn’t move to implement the changes suggested by the NRA report right away. But in 2016 he recruited Cole, a professor of constitutional law at Georgetown University, to be the group’s new national legal director. Earlier that year, Cole had published a book, Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law, which profiled three movements: the fight for marriage equality, the effort to rein in the Bush administration’s war on terrorism—and the rise of the NRA.

Cole argued that despite the popular understanding of constitutional law as something dictated by the courts, it was in fact much more of a democratic process than people realized. “It is not so much imposed top-down by judges with life tenure, as built from the bottom up by citizens engaged in democratic participation,” Cole told an audience at Politics and Prose, an independent bookstore in Washington, D.C., shortly after his book was published. Many of the major changes in constitutional law were shaped by campaigns from civil society groups before making their way through the legal system. Before Obergefell v. Hodges, there was the national campaign to win support for gay marriage led by Evan Wolfson and other LGBT rights activists. Before District of Columbia v. Heller, there were the tireless efforts by Marion Hammer and other NRA activists to expand gun rights in the states.

“To focus on federal judges and courtroom lawyers is therefore to miss much of the story—and probably the most important part,” Cole wrote in his book. “Look behind any significant judicial development of constitutional law, and you will nearly always find sustained advocacy by multiple groups of citizens, usually over many years and in a wide array of venues.” The takeaway, he told the crowd at Politics and Prose, was obvious: “If you care about the Constitution, therefore, you ought to get engaged and work with those organizations that share your values.”

Of the three movements Cole studied in the book, he told the audience that the rise of the NRA stood out. The gun rights group was “probably the most effective civil liberties organization in the United States,” he said, because “it understands the inextricable link between constitutional rights and democratic engagement.”

Cole’s thinking aligned closely with Romero’s. “There was very much a mind meld with his book,” Romero said. In July 2016, Cole agreed to join the ACLU and began overseeing the group’s litigation efforts—which at the time consisted of more than a thousand cases in state and federal courts. On election night, Cole realized the job would be radically different than he’d initially imagined, and he started thinking about how the lessons from his book could apply to the Trump era. The protests that sprang up after Trump’s victory represented just the sort of activism that’s necessary to spur larger societal changes, he believed—the energy simply needed to be channeled effectively. “This is a very dangerous moment,” Cole said. “But it’s also a huge opportunity, if citizens respond by coming together and standing up for civil rights and civil liberties.”

The ACLU began the Trump era by promising to challenge the president legally at every turn—a tough stance, but a necessary one with a president who behaves as though he is unbound by the law. As the organization’s legal director, it was Cole’s job to fulfill the ACLU’s promise to see the president in court. But Cole himself viewed the courtroom strategy as just one component of a broader mission. And now that the ACLU was looking to extend its influence beyond the courtroom, it needed someone with a plan to create a political movement it could call its own.

Faiz Shakir first discussed his vision for a different kind of organizing wing within the ACLU in 2015—the same year Shakir’s boss, Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, announced his retirement. “I pitched them on the idea of becoming a grassroots organization,” Shakir said recently, in an interview in his office. “You have a membership that you could deploy to be real muscle for this organization.” Romero was interested, but what Shakir was proposing was a big change for the group, and he didn’t immediately offer him a job. After Trump was elected, though, Romero changed his mind. Shakir became the ACLU’s new national political director on the morning Trump took office.

Inside the ACLU, Shakir said, “more like the NRA” had already become shorthand for getting results. “Over time they’ve built a strong organizing hub that exists in statewide campaigns and national campaigns. It’s a credit to them,” Shakir said of the NRA. “It’s lasting, which is our goal.” The ACLU didn’t simply want to enjoy a “Trump-moment bump,” he said. “This is infrastructure that we’re building.”

Around the same time that the ACLU held its rally in Florida, it launched a digital platform designed to help train and organize activists in their communities. One of its tools, a map of the United States that functions as a digital bulletin board, is meant to be a place where both ACLU affiliates and individuals can post about their events—everything from informational sessions on net neutrality to voter registration drives to candidate forums for local district attorney races—and volunteers can sign up to attend them. According to Virginia Sargent, the digital organizing director for the People Power initiative, the goal is “to make sure that there’s always a way for someone to take action with the ACLU on a given day.” Participants can sign up to participate in walkouts to protest gun violence or find ways of getting involved even if they live far away from the action. Sargent pointed to a cattle rancher in Utah who spends his nights and weekends helping to mobilize Michigan activists on an ACLU campaign to make it easier to vote.

Shakir and Newman also developed policy proposals that local activists could put before their elected officials. The first major campaign focused on protecting undocumented immigrants from the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown. Cities across the country, from Ann Arbor, Michigan, to Albany, California, have implemented ACLU-inspired rules to prevent local law enforcement officers from assisting in federal deportation efforts—a significant impediment to the Trump administration’s efforts to deport undocumented immigrants in their communities.

They’re also working to allow more early voting and online voter registration, create independent redistricting commissions, and restore voting rights to the formerly incarcerated, among other priorities. Shakir and Newman have worked with each of the ACLU’s affiliates to develop plans tailored to each state. As in the immigration effort, the broad themes are set by the national office, but the specifics of how the campaigns are carried out are determined by the state affiliates and local activists. In Florida, for example, activists are working to restore voting rights to former prisoners, while in Michigan the focus is on a ballot initiative aimed at making it easier to register and vote.

Shakir recognized that the People Power project made some of the ACLU’s state affiliates uneasy, and he has taken pains to emphasize that the group remains committed to nonpartisanship. “The ACLU takes its nonpartisan status very seriously,” he wrote in a blog post on the group’s web site in January, when announcing that the ACLU would be getting involved in electoral politics. “We are not nonpartisan merely out of tradition or to protect our tax status; we are nonpartisan because our commitment to civil rights and civil liberties drives everything we do.”

That may be true in principle but less so in practice when so much of the energy the ACLU is benefiting from is generated by the Republican occupying the White House. In the past, members might just send in a donation and then be more or less passive supporters of the ACLU as it did its work in court. After Trump’s election, “people wanted to organize in their communities,” said Alessandra Soler, executive director of the Arizona affiliate. “They wanted to do more than send in their $20 membership check.”

Though the ACLU is typically thought of as a nonpartisan group of lawyers, that is an incomplete picture of the organization’s history. The ACLU’s first director, Roger Nash Baldwin, was a social worker, not a lawyer. In 1919, he emerged from a stint in prison, for refusing to comply with the draft, as a supporter of the International Workers of the World, a labor union that advocated organizing as a means to peacefully overthrow the capitalist system. At the time, powerful industrialists and law enforcement officials were waging war on union activists, and Baldwin saw the newly founded ACLU as playing a direct role in their efforts to fight back. “The cause we now serve is labor,” went one of the organization’s earliest documents, believed to have been written by Baldwin. The ACLU’s predecessor, the National Civil Liberties Bureau, had been on the losing end of efforts to protest the suppression of political speech during wartime, and the experience made Baldwin deeply suspicious of the idea that civil liberties could be expanded through the courts. He favored public agitation, picketing, and protest—even when that meant the risk of arrest. Though he tried to recruit conservatives to the cause in the early years, the organization was dominated by leftists, and litigation wasn’t the group’s top priority, in part because the courts were unsympathetic.

“When the ACLU was founded in 1920, there were hardly any lawyers within the organization, and to the extent that it pursued litigation, it was basically doing it to show the hypocrisy of the courts,” said Laura Weinrib, a law professor at the University of Chicago and the author of The Taming of Free Speech, a history that details the radical roots of the civil liberties coalition. “It’s counterintuitive from today’s perspective, where we think of the ACLU as fully committed to a litigation strategy. That wasn’t true at its inception.” It took over a decade, and a series of incremental victories in the courts, for the litigation approach to win wider favor within the group.

“Though Baldwin wore his contempt for the legal process like a badge, he and others repeatedly invoked the imagery of ‘old fashioned American liberties,’ ” University of Nebraska at Omaha professor Samuel Walker wrote in his history of the organization, In Defense of American Liberties. “Their tactic of reading the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, or the Bill of Rights in free speech fights was a calculated appeal to patriotic sentiment. It was an exercise in mythmaking.”

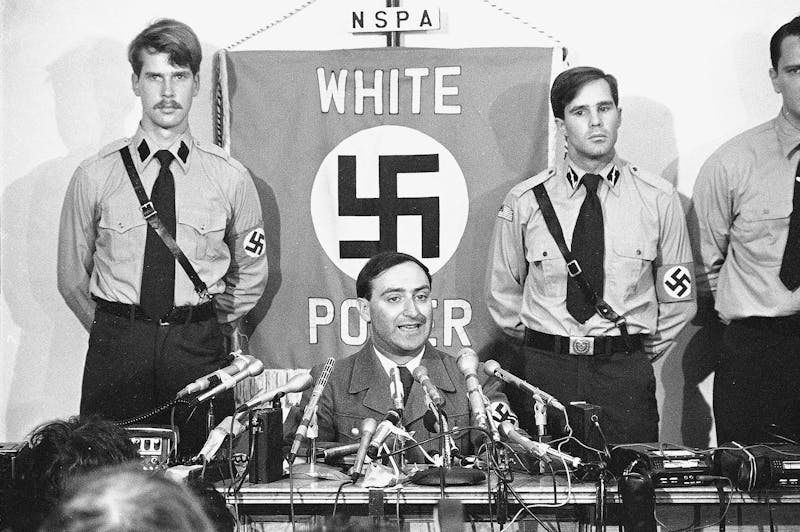

“To those who advocate suppressing propaganda they hate,” ACLU leaders argued in 1934, “we ask—where do you draw the line?”In the early 1930s, the rise of the Nazis and their supporters in America sparked important questions for the organization. There was considerable debate over whether the group should work to fight the rise of fascism at home and abroad. According to Walker, Baldwin wanted the organization to join the anti-Nazi efforts in a more active way, but the majority of the ACLU’s board favored staying focused narrowly on the defense of speech in America, no matter how abhorrent.

In October 1934, as Nazis were consolidating power in Germany, the ACLU published a pamphlet explaining why it had decided to defend the rights of Nazis to organize in the United States. Those who criticized its decision, the group’s leaders wrote, failed to understand why maintaining the principle was in their self-interest. “If the Union yielded to such critics, and condoned the denial of rights to Nazi propagandists, in what position would it be to champion the rights of others?” they argued. “Shall we choose to defend only progressive or radical causes? And if we do, how best can we defend them? Is it not clear that free speech as a practical tactic, not only as an abstract principle, demands defense of the rights of all who are attacked in order to obtain the rights of any?” The only way to protect free speech as an absolute right, the ACLU argued, was to defend it everywhere. “To those who advocate suppressing propaganda they hate, we ask—where do you draw the line?”

Defending hate speech has always been just one part of what the ACLU does, however. The group and its affiliates spent much of the twentieth century expanding the range of civil liberties protections Americans enjoy today, and they proved to be essential allies in the most important civil rights battles: joining the NAACP in its efforts to end segregation and expand legal protections for African Americans, denouncing the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and fighting for women’s reproductive freedom and LGBT rights.

But the ACLU’s defense of far-right speakers has always caused fractures in its coalition. In 1960, the group lost 1,000 members after defending American Nazi Party founder George Lincoln Rockwell in his efforts to secure a permit for a rally in New York’s Union Square. In 1977, it famously defended the right of a neo-Nazi group to march through Skokie, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago that was home to many Holocaust survivors. The group’s position in the case enraged the community and many of its members; some 10,000 reportedly abandoned the ACLU, and the loss of financial contributions helped put the organization into debt. The National Lawyers Guild charged the ACLU with “poisonous evenhandedness,” saying that it had “betray[ed] the cause of civil rights.” But its leaders steadfastly defended their decision to get involved. “If we don’t belong in Skokie, I don’t know where we belong,” Norman Dorsen, then the ACLU’s president, told The New York Times in 1978.

Still, the ACLU was able to rebuild and grow. Its membership expanded during the social conservatism of the Reagan era, and it got another public boost of support when George H.W. Bush famously attacked Michael Dukakis during the 1988 election for being a “card-carrying member” of the ACLU. But the rise of campus speech codes in the 1990s opened divisions in the organization that continue to this day.

There are also disagreements about where the group’s priorities should lie. Last year, the ACLU agreed to represent Milo Yiannopoulos when the Washington Metro Area Transit Authority tried to ban advertisements for his new book from city subways and buses. One ACLU lawyer, Chase Strangio, a staff attorney with the organization’s LGBT & AIDS Project, publicly criticized the group’s decision to represent Yiannopoulos. “Though his ability to speak is protected by the First Amendment, I don’t believe in protecting principle for the sake of principle in all cases,” he said in a statement released on Twitter. “The ability to speak and protest and disrupt is already affected by one’s race, class, immigration status, religion, and gender. Black bodies, for example, are already always criminalized by our system, so the idea that the speech of Black Lives Matter is being defended through the representation of someone like Milo is a farce in my view.”

In response to the public criticism, another ACLU lawyer pointed out that the group has a long history of defending hateful clients and said the criticism was an inevitable by-product of fulfilling its mission. “We did expect some unhappiness,” Arthur Spitzer, legal director of the ACLU-D.C., told The Washington Post about the decision to come to Yiannopoulos’s aid. “We always get some when we defend unpopular people.” But the Trump era has ushered in a dark chapter in American history, and the ACLU had publicly staked out a clear position: in confrontation with the president and opposed to bigotry and hatred. Just days after the Yiannopoulos controversy, another event would take place that caused some of those new ACLU supporters to wonder: Was the group now giving cover to the enemy?

If one incident exemplifies the ACLU’s historical role as a nonpartisan advocate for free speech, it is its defense of the right of neo-Nazis to demonstrate in Skokie, Illinois. After prevailing at the Supreme Court in 1978, Frank Collin, leader of the National Socialist Party of America, called off the protest. Fred Jewell/Associated Press

If one incident exemplifies the ACLU’s historical role as a nonpartisan advocate for free speech, it is its defense of the right of neo-Nazis to demonstrate in Skokie, Illinois. After prevailing at the Supreme Court in 1978, Frank Collin, leader of the National Socialist Party of America, called off the protest. Fred Jewell/Associated PressOn the night of August 11, hundreds of tiki-torch-bearing white nationalists marched through Charlottesville, Virginia. The ostensible purpose of the march was to protest the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue from a city park, and the ACLU had helped prevent Charlottesville officials from moving the protest to another location. But the real reason for the nationalists’ gathering—to assert themselves as a newly resurgent force in America, the shock troops of racist and anti-Semitic violence in the Trump era—quickly became apparent. The following day, the white nationalists harassed, assaulted, and beat counterprotesters, and the violence culminated in the murder of one of the anti-racist protesters, a 32-year-old named Heather Heyer.

In the immediate aftermath, the ACLU’s role in representing the white nationalist who organized the rally became the subject of intense criticism. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe noted that state officials had tried to move the rally away from downtown. “We were unfortunately sued by the ACLU,” he said. Waldo Jaquith, one of the board members of the Virginia ACLU, announced his resignation from the organization, saying, “I won’t be a fig leaf for Nazis.” On social media, people who had given money to the ACLU earlier in the year expressed their fury with the group. Critics on Twitter accused the ACLU of having “blood on its hands.”

In The New York Times, K-Sue Park, a critical race studies fellow at UCLA’s School of Law, wrote an op-ed that encapsulated the liberal criticism of the organization. It was time for the ACLU to rethink its approach to taking on the free speech cases of white supremacists, she wrote. Her argument echoed Strangio’s: There are communities whose free speech is threatened all the time in ways that might not make for a good First Amendment case but are still critically important. “The danger that communities face because of their speech isn’t equal,” Park wrote. “The ACLU’s decision to offer legal support to a right-wing cause, then a left-wing cause, won’t make it so.”

ACLU staffers were also critical of the organization’s decision to defend white nationalists in Charlottesville. Two hundred staff members signed a letter arguing that the ACLU’s defense of neo-Nazis was hurting the group’s efforts to fight for racial equality. “Our broader mission—which includes advancing the racial justice guarantees in the Constitution and elsewhere, not just the First Amendment—continues to be undermined by our rigid stance,” the letter stated.

On a conference call, staff members debated what the group should do going forward. “People were saying, ‘Let’s come up with a set of criteria to decide how to take a case like this,’ ” said one ACLU staffer, who was not authorized to speak to the press and therefore requested anonymity. “That’s not the question here. The question is, what is the focus of our work? How do we defend the First Amendment? Why is it more important than the Fourth Amendment?”

“It’s hard for an organization to say we’ve done work against racism and we actually perpetuate it in many ways,” one ACLU staff member said.“There’s a million other cases where people’s rights to express themselves are under attack,” the staffer said. “In a way it feels like, look how cool it will look if we defend the American Nazi Party. I think it’s hard for an organization to say we’ve done work against racism and we actually perpetuate it in many ways—not intentionally, but we perpetuate it. We need to look at ourselves.”

For his part, Cole said that the events in Charlottesville have not changed the ACLU’s fundamental approach, and that it is possible to defend speech that liberals might find abhorrent while still fighting for the rights of minorities. “We have to do the best we can to defend all of those rights and be conscious of the costs when we’re defending the rights of white supremacists,” Cole said. “We may defend their right to speak, but we can also be very clear that we absolutely disagree with what they’re saying. We can double down on fighting for racial justice as we’re doubling down on protecting free speech.” If, at times, those two agendas seem to come into conflict, Cole said, the ACLU will need to think carefully about how to proceed. “We can’t say we won’t ever do these kinds of cases or we’ll always do these kinds of cases,” he said. “We have to take it on a case-by-case basis. That’s the best one can do.”

That may be the best that an organization committed to both civil rights and the protection of all forms of speech can do. But it’s a response that will almost certainly be unsatisfying to those who feel threatened by the resurgence of white nationalism in America, and for whom the issue feels less like a careful balancing of principles and more like a matter of life and death. They might wonder how the group can possibly predict how much damage defending white supremacists will cause. For a significant portion of the left, there is no scenario in which defending a neo-Nazi will be more important than fighting for the rights of immigrants, minorities, women, and other oppressed groups. As long as the ACLU remains committed to both causes, those tensions around the group can never really go away.

But the events in Charlottesville do seem to have caused the ACLU’s leaders to do some soul-searching. Shortly after the violence there, the ACLU of California declared in a statement that “if white supremacists march into our towns armed to the teeth and with the intent to harm people, they are not engaging in activity protected by the United States Constitution. The First Amendment should never be used as a shield or sword to justify violence.” And though the organization’s national leaders still think the ACLU of Virginia made the right call based on the merits of the case, Romero endorsed the California branch’s statement, saying that, going forward, the organization will not defend hate groups that plan to march with weapons. “It was a moment of learning for us, and for the country,” Romero said.

The ACLU’s push into grassroots organizing, meanwhile, has invited a different kind of criticism: that it’s abandoning its core identity as a nonpartisan group. “Much as the National Rifle Association has become something of an organ of the Republican Party, the ACLU leadership now apparently seeks to become a hub for liberal Democratic activism. Whatever you think of that desire, it cannot comfortably coexist with the ACLU’s historic mission,” former Senator Joseph Lieberman wrote in an op-ed for Real Clear Politics earlier this year. “Some principles—like free speech—should transcend party. It is bad for our democracy when groups like the ACLU are viewed through a partisan lens.”

In an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal last year, Wendy Kaminer and Alan Dershowitz, both former ACLU board members who have been among the group’s most pointed critics, accused the ACLU of liberal bias. “The ACLU was once a nonpartisan organization focused on liberty and equality before the law. In recent years it has chosen its battles with an increasingly left-wing sensibility,” they wrote. “In doing so, it has become considerably more equivocal and sometimes even hostile toward core civil liberties concerns of free speech and due process.” But the ACLU rejects that argument. The Trump administration, it says, is antithetical to American values, not partisan ones—there’s a reason why, despite high levels of partisanship, Trump has so many conservative critics. “Vulnerable populations in America are being targeted in a systematic way by Trump and being robbed of liberty. The Muslim ban, the separation of immigrant families seeking asylum, the transgender military ban, the ban on abortions of undocumented minors,” Shakir said. “These aren’t concerns driven by a ‘left-wing sensibility’.… Anyone who is content with defending a president who would restrict these liberties is on the wrong side of history.”

Still, the criticisms point to a larger truth about the ACLU. It sits at the center of a large, ideologically sprawling coalition of Americans connected by their concern for civil liberties but with wildly different ideas about what the group’s priorities should be. That almost ensures that the ACLU will face criticism that its priorities are wrong, or that it’s lost its way—particularly at moments when the ACLU enjoys an influx of public support. But it’s a difficult balancing act to be both the nonpartisan leader of a civil liberties coalition and the leader of the opposition to Donald Trump. “We’ve been called a leader of the Resistance, and we are proud to be a part of the resistance to the anti–civil liberties and anti–civil rights policies of Donald Trump,” said Romero, trying to draw a distinction between the ACLU’s opposition to the president on certain issues and the wholesale opposition of many of Trump’s detractors. “Where it gets complicated is that for some people their resistance is partisan: A Republican that we really don’t like is in power, and we must resist for that reason,” Cole said. “That is not the reason we’re resisting.”

“Messy, disruptive, loud—that’s what democracy looks like,” Romero told the crowd of activists gathered at the People Power launch in Florida last March. He was speaking generally, but he could have been describing the ACLU, too. The organization has already scored decisive victories against Trump’s abuses of power, and it will certainly play a central role should the president fire special counsel Robert Mueller over the Russia investigation or trigger a constitutional crisis some other way. But as long as the current political trends hold, the ACLU’s role in the Resistance will continue to be limited by its commitment to defending partisans across the political spectrum. The NRA has taken advantage of today’s political polarization by adjusting its resources accordingly. By moving into the realm of electoral politics, the ACLU is attempting something similar—but its history, and its commitments, keep it from being able to fully embrace the change. Resistance of a different kind—to the ideological boundaries that increasingly define our politics—is still too much in its DNA. As long as that remains the case, the liberals who hope that the ACLU will satisfy all of their hopes and dreams are bound to be disappointed.

Eight years ago, a New York resident and long-shot gubernatorial candidate named Jimmy McMillan became briefly, rightfully famous on the internet and the late-night talk-show circuit, and not just because of his immaculate facial hair. “The rent is too damn high,” his campaign slogan, inspired memes and a now-defunct political party, but it didn’t just resonate because it was funny.

That slogan, still quoted regularly in news outlets around the country, is as true as ever. And while McMillan’s policy prescriptions were sometimes impractical—he called for reducing all rents to 2001 levels—the issue has recently received more serious treatment from aspiring politicians. In New York, gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon and state Senate candidate Julia Salazar, both Democrats who have affiliated themselves with democratic socialism, are running on expanded rent control policies. And in California this fall, voters will have the power to repeal a law restricting rent control on newer units.

Many American renters are in crisis: The Pew Charitable Trusts found that the share of “rent-burdened” households—those which spent at least a third of pre-tax income on rent—rose from 19 percent in 2001 to 38 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, multiple factors—including the Great Recession, still-stagnant wages, and demographic trends—have caused a steady increase in Americans who rent, to a 50-year high (and a concurrent decline in homeownership). With several of those trends showing no sign of slowing, the percentage of renters likely will continue to rise—and so will the political importance of rent policies.

Both Nixon and Salazar are calling for an expansion of rent stabilization and to close loopholes that undermine the few protections that already exist. They both call for the end of vacancy decontrol, which allows landlords to deregulate an apartment’s rent after a tenant vacates, and preferential rent, which allows landlords to drastically increase rent on units that have been rented below the legal maximum. Nixon, who calls her rent platform the “most progressive and expansive tenant protection program in the country,” also supports the passage of just cause legislation, which would prevent landlords from evicting tenants without providing reason to do so.

Rent control is illegal in 27 states. Even in cities and states that enforce some version of rent regulation, affordable homes have become an endangered species, due to legal loopholes and landlords who deliberately break the law. New York City recognizes two categories of rent regulation: Apartments can either be rent-controlled or rent-stabilized, with the latter being far more common than the former. The distinction between the two depends largely on the date and size of the building. Rent-controlled apartments are located in buildings constructed before February 1, 1947, and have been occupied continuously by tenants since before 1971. Apartments in buildings of six or more units built before January 1, 1974, are rent-stabilized. But as The New York Times reported in May, New York City has lost 152,000 rent-regulated apartments since 1993 because landlords have used legal loopholes to raise rents, and it has lost another 130,000 apartments because they were converted to co-ops and condos.

The loopholes that Nixon and Salazar want to close have directly contributed to the crisis. Preferential rent, which allows New York City landlords to charge tenants a rate below an apartment’s market value, sounds like it should be a benefit for renters—and sometimes it is. But as a 2017 ProPublica investigation noted, “Increases in preferential rents aren’t subject to city-set limits governing other rent-stabilized apartments. Landlords can revoke the preferential rates, and hike rents to the legal maximum, whenever leases come up for renewal. That can mean spikes of hundreds or even thousands of dollars.” Some landlords entice renters with low preferential rents, only to spring a massive increase to the legal rent—which sometimes has been illegally inflated—once the lease is up.

Los Angeles, California, also enforces a version of rent control, but it’s limited. It only applies to multi-family buildings, and, as in New York City, it doesn’t apply to buildings built after a certain date. The city’s rents, meanwhile, have steadily increased. Writing for The Nation this year, Bryce Covert reported that over half of Los Angeles renters pay at least 30 percent of their monthly income in rent, and the city has “the severest shortage of affordable housing for its poorest renters, with just 17 homes for every 100 extremely low-income families.” The Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act prohibits California cities from placing rent caps on buildings built after 1995, which prevents cities like Los Angeles, or its northern neighbors in the Bay Area, from regulating rents on newer units.

Opponents of Costa-Hawkins collected enough signatures to get a proposition to repeal it on November’s ballot. Voters and legislators in Illinois, where rent control is illegal, may soon have their own chance to deliberate the future of rent in their communities. In March, voters in nine Chicago wards affirmed a question asking if the state should repeal its prohibition on rent control. This is not the equivalent of voting to repeal the law, but it indicates a well of public support for rent control. A bill to lift the ban stalled in the Illinois state legislature this year.

Rent control has its opponents—not just landlords, but many economists. “Almost every freshman-level textbook contains a case study on rent control, using its known adverse side effects to illustrate the principles of supply and demand,” Times columnist Paul Krugman argued in 2000. A 2017 study by Stanford University economists purportedly found that while San Francisco’s vestigial rent control law increased the likelihood that a long-term tenant would be able to stay in their home, it reduced housing supply.

J.W. Mason, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, concedes that many economists disdain the concept of rent control, but it isn’t a sentiment he shares. “What is the reasoning behind it? Is there some sort of sophisticated analysis or historical data? No. The reason is very simple. If you limit the price of something, then it won’t be as profitable to produce it, so people will produce less of it,” Mason explained. “But when you take a step back and you think about it, this is an argument against price controls in general, because that’s really what the argument against rent controls is.”

Housing, he noted, lasts a long time, especially in cities like New York. “When you’re talking about a decision about producing housing, typically that’s a decision that was made a long time ago,” he said. “The fact that you you can’t charge as high a rent as you might otherwise want to doesn’t change your decision about how much housing to produce out of that building this year, because that’s fixed by the size of the building.”

Samuel Stein, author of the forthcoming Capital City: Urban Planners in the Real Estate State, told me that while rent control is only one way to reduce housing inequality, it plays a vital role. “I think it’s the best way to protect tenants from a certain kind of gentrification, and that’s the gentrification that results from something happening to your neighbor,” he said. “If a big luxury building goes up right next to you, in theory it should have no impact on your rent. But it always does, unless there’s a mechanism to prevent that from happening or if the government makes some sort of positive intervention in your neighborhood. You shouldn’t suffer as a tenant because your land values are higher and the landlord has been able to pass that benefit to the public onto tenants as an extra cost.” Stein also cites public housing and an end to land speculation as other means to increase the availability of affordable housing.

Other economic trends indicate that the question of rent control will only become more important. The U.S. Federal Reserve, citing falling unemployment, has increased interest rates and indicated it will probably do so again, which is certain to increase the cost of home mortgages. And while the unemployment rate is at 4 percent, wages remain largely stagnant. A July 12 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that average hourly earnings for American employees grew by only 0.1% from May to June. For production and non-supervisory employees, hourly earnings decreased by 0.2 percent from June 2017 to June 2018.

The federal minimum wage provides another stark example: It hasn’t been raised since 2009. Because it hasn’t kept pace with inflation, the Pew Research Reports, the minimum wage has lost around 9.6 percent of its purchasing power. An American worker making minimum wage for the last ten years earns less money per hour now than they did in 2008. And if wages stay stagnant while interest rates go up, American workers will find it increasingly difficult to buy homes and will remain in the rental market. There’s some evidence that this is already happening. According to the Census Bureau, the number of American homeowners has decreased from a high of 69 percent in 2005 to 64 percent in 2018.

With more Americans dependent on rentals, while their wages barely rise, rent control isn’t just an issue for residents of New York City. It will instead become more relevant to voters everywhere. Nixon’s and Salazar’s proposals might make sense politically, since rent is a reliable pocketbook issue, but they also make sense economically—even morally.

“At least one of the major purposes of rent control is to recognize the right of a longtime tenant to remain in their home,” Mason said. “And there’s an economic reason behind that, because people who have security are going to take better care of the place, and they’re going to be more invested in the neighborhood. A lot of the value of housing and of the value of urban land comes from the activity of the people who live there, and from the very things they do to create a community where other people want to live.”

No comments :

Post a Comment