New Mexico Senator Tom Udall has been on a months-long mission to solve one of the enduring mysteries of the era: What’s in President Donald Trump’s tax returns?

Udall, a Democratic member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, sparred with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo over that question—and not for the first time—during a hearing on Wednesday. Udall said Trump’s secrecy surrounding the Helsinki summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin only made that question more urgent. “After Helsinki, don’t you think Americans deserve to know what’s in President Trump’s tax returns and business interests that are intertwined with Russia?” he asked.

“I’m going to stay out of this political circus,” Pompeo replied, adding that the Trump administration had taken steps contrary to Russian interests.

On Thursday morning, Udall was back at it, appearing on MSNBC’s Morning Joe saying he would support legislation to force presidential candidates to publicly release their tax returns. “I think it’s very important that people know if there are conflicts of interest that the president might have, that we clear that up,” he replied. “The easiest thing to do here is just disclose all the tax returns.”

What Udall didn’t mention is that Congress doesn’t need legislation to release the president’s tax returns. If Democrats retake either the House or the Senate this fall members of the tax committees can obtain Trump’s tax returns directly from the IRS by using a provision in federal law that grants those committees special access to help craft legislation.

“Following Watergate, Congress changed the law to eliminate the president’s ability to order a disclosure [of other people’s tax returns],” George Yin, a University of Virginia law professor who previously worked for Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation, wrote in February. “But it retained the right of its tax committees to do so as long as a disclosure served a legitimate committee purpose. Such a disclosure must be in the public’s interest, and today’s understandable concerns about Trump’s potential conflicts of interest would seem clearly to justify a congressional effort to obtain, investigate and possibly disclose to the public his tax information.”

Democrats are slightly favored to retake the House, and have a remote chance of retaking the Senate as well. In theory, controlling Congress would give them the opportunity to enact their legislative agenda. It wouldn’t be easy: Trump would almost certainly veto any substantive Democratic legislation that reached his desk. With Congress so deeply polarized, Democrats would have an extraordinarily hard time attaining the two-thirds majority necessary to override a veto on most of their key policy preferences. And that’s if they controlled both chambers, which is unlikely.

With ordinary lawmaking off the table in most cases, what’s a Democratic legislator to do? Some want to impeach the president, but the answer may lie in the network of almost four dozen congressional committees, through which lawmakers exercise most of their power. The power to request sensitive documents, subpoena reluctant witnesses, hold high-profile hearings, and even look at the president’s tax returns should give Democrats all the incentive they need to retake Congress.

“Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee-rooms is Congress at work,” Woodrow Wilson wrote in 1885, years before entering politics. Lately, under Republican control, Congress in its committee-rooms has been a lot like Congress in session.

Democratic lawmakers held almost four dozen public hearings ahead of the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2009 and 2010; Republicans held only two of them in 2017 during their failed bid to repeal the law, which governs one-sixth of the American economy. While GOP lawmakers hosted tax-related hearings for years in advance of last year’s tax-reform law, they held none on the final legislation. And so far Scott Pruitt, the former EPA administrator, is the only Cabinet member who has attracted bipartisan oversight scrutiny for a seemingly endless series of corruption allegations.

So what have GOP lawmakers been up to instead? Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing in April to explore whether Facebook and other social-media giants were censoring conservative voices (for which there’s no evidence). Among the invited guests were Lynette Hardaway and Rochelle Richardson, two staunchly pro-Trump video bloggers known as Diamond and Silk. New York Representative Jerrold Nadler, the committee’s Democratic ranking member, complained in a statement, “House Republicans have no time for substantive oversight of the Trump administration, or election security, or privacy policy, or even a discussion about the wisdom of regulating social media platforms—but they have made time for Diamond and Silk.”

The Russia investigation has been another major target for House Republicans. Earlier this month, the House Oversight and House Judiciary committees held a joint hearing to question Peter Strzok, a FBI counterintelligence agent who took part in the Clinton email inquiry and the early stages of the Russian election meddling investigation. Trump’s allies have seized on Strzok’s text messages with FBI lawyer Lisa Page to claim bias within the FBI against the president. Those attacks culminated in nearly ten hours of public interrogation earlier this month about the texts, which ultimately revealed nothing that would undermine special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation.

Perhaps the biggest implosion has come from the House Intelligence Committee, which is tasked with providing congressional oversight to the nation’s vast intelligence apparatus in a sensible, bipartisan manner. Since Trump took office, Republicans on the committee have steadily turned it into a partisan weapon against FBI and Justice Department officials for investigating the extent of illegal coordination between Moscow and the Trump campaign during the 2016 election.

So, what could Democrats do with this power instead? Unlike virtually every other major-party candidate since Watergate, the president refused to release his returns during the presidential campaign, claiming that he couldn’t because he was being audited. Many, like Udall, have speculated as to whether the documents would reveal evidence of money laundering or colluding with Moscow. As a result, obtaining the returns has become something of a holy grail for Democrats and liberal activists alike.

By all accounts, Trump’s tax returns are being treated like something akin to a state secret. John Koskinan, who retired as IRS commissioner last year, told Politico even he didn’t have access to them. Under federal law, however, Congress’ tax committees can request a copy of any taxpayers’ returns directly from the IRS, ostensibly to aide in the development of a better tax code. An intrepid legislator could then publicize what they find in Trump’s tax returns by reading them aloud on the floor of Congress, just as Alaska Senator Mike Gravel did with the Pentagon Papers. The Constitution’s Speech and Debate Clause protects lawmakers from criminal and civil prosecution during the course of their official duties. There might be a political price to pay, but if what they find is damning enough, the representative or senator might find it worth the cost.

Trump isn’t the only executive-branch official who could come under greater scrutiny if the Democrats retake the committees. Most of the standing committees have the power to subpoena witnesses and documents, a valuable tool that’s inherent to the legislative process. But with the exception of Pruitt and his cavalcade of scandal, Republicans have largely avoided digging too deeply into the Trump administration’s top officials.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’s shady financial dealings, for example, prompted Democratic ranking members on eight different committees to request an ethics probe from the department’s inspector general. House Oversight Democrats have also sought more of his records related to the Census Bureau’s controversial decision to add a citizenship question to the decennial census in 2020. Documents released by the department this week in a lawsuit over the question showed that Ross actively pushed for it to be added, contradicting his earlier testimony before Congress.

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s ethics scandals also merit greater scrutiny. Democrats on the House Natural Resources Committee called for investigations in April into whether misused his position to politically benefit Florida Governor Rick Scott, and whether the National Park Service is violating its scientific-integrity policy by deleting references to climate change. Zinke has drawn attention from House Democrats for forcibly reassigning some career Interior Department personnel to lesser posts; the secretary remarked last year that he perceived 30 percent the department’s staff to be “disloyal” to the president. Some Republicans have even shown interest in Interior’s buying habits: Oversight chairman Trey Gowdy sent a letter to Zinke in March requesting details on a $139,000 door the department reportedly bought for Zinke’s office.

Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson’s lavish spending spree on office furnishings and other professional accoutrement also warrant a closer look. Frank Pallone, the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s ranking member, asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in February for more information about the noncompetitive bidding process that awarded a $485,000 contract to a company led by Carson’s daughter-in-law. The next month, Democrats on the Senate Banking Committee grilled Carson about his alleged hirings of unqualified but well-connected political allies.

Looming over all of this is the Russia investigation. House Republicans’ efforts to hamstring Mueller’s investigation have damaged Congress’s ability to probe Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein’s decision to appoint Mueller as special counsel last year quelled a push among Democratic lawmakers for an independent commission to study what happened during the 2016 election. But a Democratic-led House could opt to assemble a special committee on Russian interference akin to the House Benghazi Committee that Republicans used to flense Hillary Clinton and the Obama administration for five years.

The House Intelligence Committee formally closed its investigation into Russian election interference in March with a widely criticized report that found no collusion between Moscow and Trump, but Democrats could seek to reopen that inquiry if they take the House. California Representative Adam Schiff, the committee’s Democratic ranking member, has criticized his colleagues on the right for stonewalling key requests about certain personnel and their actions. Schiff said in January that Republicans had blocked Democrats’ efforts to probe Trump’s business relationship with Deutsche Bank, to obtain call records and emails from those involved in Donald Trump Jr.’s infamous meeting with a Russian lawyer, and interview witnesses like Ivanka Trump and Natalia Veselnitskaya.

If Democrats manage to retake the House in November, the first question on everyone’s lips will be: “Now what?” Policy proposals like Medicare-for-All, universal college tuition, passing a clean DREAM Act, and abolishing ICE will be front and center. But those are virtually impossible to attain under a Republican president. The true action will be in the committee-rooms, if Democrats are ready to do the work.

American farmers are furious, and President Donald Trump is trying to calm them in the only way he knows how: throw money at them.

Ever since he started his trade war, overseas sales of agricultural products have suffered, cutting deep into farmers’ already-slim profit margins. To make up for these losses, Trump on Tuesday announced $12 billion in emergency aid—a bailout that, according to The Washington Post, will include “direct payments to farmers, efforts to promote U.S. goods abroad and an expansion of a program that purchases surplus farm output and distributes it to food banks and other anti-hunger programs.”

Some farmers aren’t thrilled by Trump’s move. “I mean, I understand they’re trying to help us. I get that. But it’s not a long-term fix. It’s a pacifier, so to speak,” Dave Kestel, a soybean farmer in Illinois, told CBS News. “I’d rather not have it.” And Trump has been widely criticized in Washington, even by members of his own party:

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is trying to put a band-aid on a self-inflicted wound. The administration clobbers farmers with an unnecessary trade war then attempts to assuage them with taxpayer handouts. This bailout compounds bad policy with more bad policy.

— Senator Pat Toomey (@SenToomey) July 24, 2018Tariffs are taxes that punish American consumers and producers. If tariffs punish farmers, the answer is not welfare for farmers — the answer is remove the tariffs.

— Senator Rand Paul (@RandPaul) July 24, 2018Trump’s trade war may be new, but welfare for farmers is not. Indeed, the fact that $12 billion in aid is widely seen as a meager, temporary solution only highlights the broader problem: The American food system is broken, and has been for a long time.

There’s little doubt that Trump’s tariffs are punishing farmers. After the United States taxed imports of more than 800 Chinese products this month, Beijing responded by taxing 545 American items, including soybeans, rice, beef, nuts, pork, dairy, and produce. Much of the agricultural industry relies on exports to survive. Pork producers, for example, send about 26 percent of all production overseas, and one-third of U.S. soybeans are sent to China each year. As a result, the average hog farmer is now losing $20 to $25 per pig, Iowa Pork Producers Association President Gregg Hora told NPR, and soybeans have fallen to their lowest prices in a decade.

But the farm industry relies so much on exports partly because the government highly subsidizes the production of food sources that Americans don’t eat or need. Since the Great Depression, Congress has been authorizing programs to prop up the industry when weather problems or market fluctuations cause prices to fall. As CNN noted on Wednesday, these programs “were originally implemented to guarantee the nation had adequate food and feed supply, which was crucial to growing the economy ... Now, however, the United States has a booming agriculture export business, which has made trade even more important to farmers.”

Thus, the government now spends an average of $16 billion annually to buy products from farmers who can’t find buyers in America or overseas. This has resulted in a massive stockpiling of food across the country. U.S. dairy producers, for example, have a 1.39 billion-pound surplus of cheese—its largest surplus on record—because they have selectively bred cows to overproduce milk, and milk is stored best as cheese. There’s also a 2.5 billion pound surplus of meat, Vox reported this week, which is partially due to Trump’s tariffs but also the waning interest in meat.

“A tangled web of ill-conceived federal policies explains a lot of the problems we see” in the food chain, Anne Kapuscinski, a Dartmouth professor and board chair of the Union of Concerned Scientists, explained in an op-ed last year. “It explains why junk foods are cheaper than fruits and vegetables (because corn and soy, key ingredients of processed foods, benefit from on-farm subsidies and taxpayer-funded research); why farmers increase planting of these crops even when prices are low (because crop insurance guarantees their income); and why some of the most food-insecure people in our country are ironically the very people who produce and prepare our food (because many farm and food service workers work in the shadows without a living wage).”

Trump’s farm bailout includes measures to handle the surplus of food, including purchasing it and donating it to food banks, which highlights yet another problem with welfare for the agriculture industry. Forty-one million Americans currently suffer from food insecurity—meaning these subsidies, which originally were intended to ensure the nation had enough food, are not working for that purpose. According to CBS, “Rural counties are among the worst-hit, comprising 79 percent of the counties with the highest food insecurity rates, even though they make up only 63 percent of all U.S. counties.”

Trump’s farmer bailout is equivalent to about one-sixth of what the U.S. spends annually on SNAP benefits, formerly known as food stamps, which help more than 40 million Americans. And yet Trump, though quick to cut a $12 billion check for farmers, seems to think even $70 billion is too much to feed the nation’s hungry: In his 2019 budget, he proposed cutting SNAP by $213 billion over 10 years, a nearly 30 percent cut. (Congress largely ignored his request.)

In addition to costing the government billions without adequately feeding Americans, the farm industry’s overproduction has also caused a veritable drinking water crisis in rural areas across the country. Nitrogen-based fertilizer from large-scale agriculture has a tendency to slide off of farmlands and into the nation’s freshwater systems, causing serious nitrate pollution in towns in the Mississippi River Valley. Drinking water with even small amounts of nitrates increases the risk of colon, kidney, ovarian and bladder cancers, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Trump’s bailout is supposed to be temporary. Eventually, he argues, the trade war will pay off—farmers will no longer need taxpayer help. “The farmers will be the biggest beneficiary. Watch,” he said. “We’re opening up markets. You watch what’s going to happen. Just be a little patient.” Is it possible that, with a long-running trade war, Trump can fix America’s broken food system? Sure, it’s possible. Perhaps when pigs fly.

In a public conversation last year, Zadie Smith spoke about the social media reaction cloud, where people can be bullied into thinking and feeling the “right” way. She said it has become harder to begin in the wrong place and then lumber one’s way towards a proper understanding of things. All of this is bad for writing, she suggested, and bad for the soul. “I want to have my feeling, even if it’s wrong, even if it’s inappropriate, express it to myself in the privacy of my heart and my mind,” she said. “I don’t want to be bullied out of it.”

The chamber of public opinion has been maligned in a lot of places. Not so long ago, Katie Roiphe made the argument in Harper’s that “Twitter feminism” was drowning out debate and originality with its bullying. But it is rare, perhaps unprecedented, to find this familiar brand of polemic tucked into the form of an oblique allegory, which is what Smith has done with a new short story, “Now More Than Ever,” in The New Yorker. It has been called “extremely reactionary” and “hip, current, but morally and politically vacant” on Twitter. But Smith probably expected as much, since social media—that bullying place where the right to be wrong is forfeited—is the story’s main nemesis.

The narrator of “Now More Than Ever” is a teacher (she signs an email as Professor) who lives on a campus that resembles New York University (where Smith herself lives). She describes a world sort of like ours, except that the volume of the internet has been turned way up. In the Professor’s apartment building, “as in many throughout the city,” the inhabitants shame each other by holding big black arrows in their apartment windows in the direction of that day’s villain.

The plot jumps from one quasi-absurd set piece to the next. The Professor hangs out with a person called Scout, watches the Elizabeth Taylor movie A Place in the Sun, and tries to dodge the inexorable guillotine of her own public shaming. A student writes to ask her to do his homework for him, quoting Hamlet’s great bit about how the world “appeareth no other thing to me, than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.” The story is written with a cold, faux-anthropological distance, applying a satirical compress to the heated passions that are the hallmarks of pussy-hat feminism, the hashtag-resistance, and the black-and-white view of public morality that, in the story’s view, govern both.

The sarcasm is evident in the story’s title, which is a catchphrase. It’s buzzy the way that wasps are buzzy in the summer: everywhere all of a sudden and annoying. The story ends with the words “me, too,” another catchphrase. But these catchphrases are used unwittingly, since the Professor is hazy about the strange new idioms and rules that now oppress her. Scout, who is apparently younger than the Professor (she’s “on all platforms”), is invited to sit at the Professor’s “mid-century-modern breakfast bar” to “unpack” the news that “the past is now also the present.”

Via a puppet show, Scout explains that our time calls for “consistency.” One puppet has very long arms and the other has a triangle for a face. Here’s the idea: “You’ve got to reach far, far back, she explained, into the past (hence the arms), and you’ve got to make sure that when you reach back thusly you still understand everything back there in the exact manner in which you understand things presently.” I don’t know about the puppets, but it sounds like Smith is satirizing our current interest in judging the past by the present’s standards.

In this world, history is just an extension of the present, and identity is formed by denouncing others. In such a world people attempt to live at the level of pure, righteous symbol. The past is nothing to them.

The crazy ones are the ones who insist that things change over time, that we should not be so quick to judge those who lived in less enlightened eras. The Professor points her own big arrow at a man named Eastman. “Not only does he not believe the past is the present, but he has gone further and argued that the present, in the future, will be just as crazy-looking to us, in the present, as the past is, presently, to us, right now! For Eastman, surely, it’s only a matter of time.”

If the story has politics, then, those politics are about history. As a catchphrase, “Now More Than Ever” is interesting because its hyperbole cuts us off from the past. It suggests we are in a special hell, unlike anything that came before. Smith turns the public condemnations of the #MeToo movement and imagines them as a philosophy of history, an existential condition. The loud and reputation-destroying method of political activism, the story suggests, encourages us to live in a fake world of idealized symbols, rather than a reality structured by experience, where things are ambiguous and people change.

In its jaunty, grinning way, Smith’s story says this project is lousy and false. It undermines both our understanding of ourselves and our ability to just be normal, flawed people. “There is an urge to be good,” the story begins. “To be seen to be good.” In the next line comes the dagger: “To be seen.” Smith writes that “things as they are in reality as opposed to things as they seem … these are out of fashion.” Everyone is guilty because they are human, Smith suggests, but in this era identity is determined by a false innocence (self-proclaimed) or an exaggerated guilt (imposed by others). The result is a world that is existentially hollowed out and intellectually vacuous; neither fun to live in nor a place for legitimate inquiry.

It’s a moralizing piece of fiction, and it lands like a blow to the head. The story’s meditations on time and history are genuinely interesting. But the overall effect is straightforwardly condemnatory, which seems like the kind of gesture Smith was trying to question.

In the second half of the story the Professor goes to see A Place in the Sun and muses on how Montgomery Clift’s character is called Eastman, just like her neighbor. She cannot help but sympathize with Clift, who is a very morally ambiguous person in the film. Clift-as-Eastman becomes a stand-in for Eastman-the-neighbor. After leaving the cinema, the Professor goes home, where she notices “that almost everyone on the sixth floor was angling their arrows upward, directly at my apartment, though I wasn’t even there. Montgomery Clift isn’t rich or happy. He’s guilty. I instinctively sympathize with the guilty. That’s my guilty secret.”

It turns out that the Professor is stuck. She condemns with her big arrow the very person whom she likes the most. Her feelings and the moral currents of her time are in direct conflict. She is both innocent and guilty, in a kind of identity crisis. In the Professor’s philosophy department, they might call it a dialectic.

But just as things start to get really engaging, Smith runs the story into a wall. The Professor meets a colleague in the street who is “beyond the pale,” persona non grata, though she talks to him anyway. He doesn’t have any victims or anything like that, just offended parties. But what if he had victims, she wonders? Well, in “an ideal world—after a trial in court—he would have been sent to a prison.”

Clearly, though, we don’t live in an ideal world where sexual harassers and criminals regularly go to prison—quite the opposite. At this point it is extremely difficult to understand what Smith is getting at. Is she serious? Or is she satirizing the lazy-brained Professor, who thinks that the authorities spend their time punishing the predators of lower Manhattan?

There’s not so much a lack of nuance here as a big privacy curtain erected around the way that Zadie Smith actually feels about the many abusers whose tenure protects them in their jobs, who can only really be damaged through publicity, because that’s the world that, say, NYU has built for them. What is Zadie Smith thinking? I cannot tell you.

The Professor ends up being “cancelled” herself. She, too, has been crushed under the arrow’s condemnatory point. She sympathized with a poet who played the devil’s advocate, saying some admiring things about a figure—“he-who-shall-not-be-named”—that now represents the ultimate taboo, the ultimate signifier of guilt and innocence.

“The right to be wrong” is neat-sounding, but in the manner of a cliche—the sort of catchphrase that “Now More Than Ever” seems to deplore. In the end the reader is left in a forest of signs pointing in conflicting directions. Which way is the right way? Is that signpost actually a big black arrow pointing at some poor victim in a window? Is this the conclusion—that we walk through a big dark wood of moral ambiguity? It’s not wrong, but I’m lost.

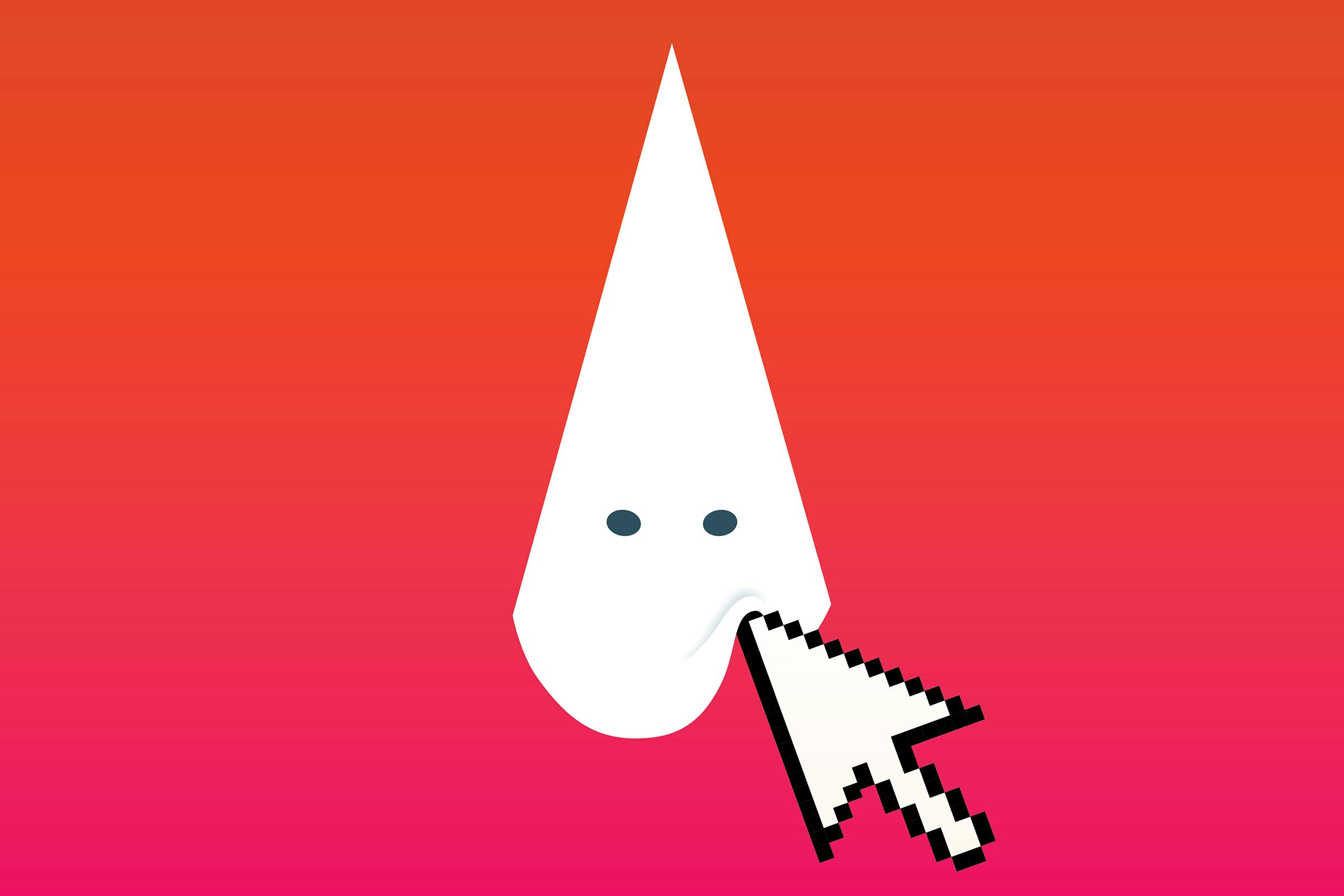

In August of last

year, a man named Andrew Dodson took part in the Unite the Right Rally in

Charlottesville, Virginia. There are videos of him marching toward Emancipation

Park, along with hundreds of neo-Nazis, fascists, skinheads, alt-righters, white

supremacists, neo-Confederates, and garden-variety racists. I remember seeing

Dodson in Charlottesville, looking out of place in a sea of khakis and army boots, of black

uniforms and lacrosse helmets and homespun shields. He wore a red Revolutionary

War–style tricorne hat and a white linen suit that made his bushy red beard all

the more conspicuous.

Initially, amateur investigators wrongly identified Dodson as Kyle Quinn, an engineer in Arkansas who was quickly subjected to a torrent of online abuse. Then, a week after the Unite the Right rally, Logan Smith, who operates the Twitter account @YesYoureRacist, revealed Dodson’s identity, or doxxed him. He published a picture of Dodson taken during the march, identifying him by name and listing a place of employment and the town where he lived. Smith exposed the identity of several other participants of the rally as well. His aim was to communicate that attending white supremacist marches came at a price. “If these people are so proud to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with white supremacists and neo-Nazis, then I think that their communities need to know who these people are,” Smith told MSNBC.

After the doxx, Dodson was reportedly let go from his job in Massachusetts. Then, on March 9, he died. For more than two months, his death went largely unnoticed, with the exception of a March 14 obituary in a local paper in South Carolina, where he was born.

In May, however, white supremacists began claiming that Dodson was a martyr to their cause. Richard Spencer called his death an act of war. RedIce TV, a Swedish far-right outlet, created a hagiographic video in Dodson’s memory, replete with throbbing hearts, dramatic black-and-white images, and somber music. The mourners asserted that Dodson had killed himself following a massive campaign of harassment, designed to isolate him from his family, friends, and employer. In a video posted to Reddit, Dodson can be seen insisting that, after the doxx, his opponents were “trying to make me lose my job, trying to threaten my family.” The actual extent of the harassment is unclear, and there is no evidence so far that his death was a suicide. (His family declined to comment for this article, as did his coroner and funeral home.) But that hardly mattered to the alt-right: The point they wanted to make, facts notwithstanding, was that Dodson’s doxxing was proof that there was no low to which the left, in its rabid thirst for blood, would not stoop.

As Laura Loomer, a former activist with the conservative group Project Veritas, famous for its misleading “sting” operations against liberal organizations like Planned Parenthood, tweeted, “Left wing insanity is killing people. This is so SAD!” In their outrage, the far right conveniently left out their own long history of doxxing. Chat logs obtained by the alternative media collective Unicorn Riot showed a concerted effort by members of the far right to release identities not only of antifa members and other left-wing activists, but also of journalists, “Marxist professors,” and “liberal teachers.”

For the leftists combating the far right, Dodson’s death, if it could be linked to his doxxing, was proof that the strategy worked.For the leftists combating the far right—a fight that has occasionally exploded into spectacular violence in places like Charlottesville, but has largely taken place on the internet—Dodson’s death, if it could be linked to his doxxing, was proof that the strategy worked. “If he did commit suicide after being doxxed, my attitude is: Thank you,” Daryle Lamont Jenkins told me. Jenkins is an anti-fascist activist, and his website, the One People’s Project, has been doxxing members of the far right for years. (Its slogan is “hate has consequences.”) Doxxing, public shaming, loss of employment, even death—all are the price you should be prepared to pay for racist behavior, according to Jenkins.

He told me that he didn’t care about the effect any harassment may have had on Dodson. He also brought up Heather Heyer, who was killed by a white supremacist in Charlottesville: “He most certainly didn’t care for Heather Heyer, so why should we care for him?”

Jenkins’s position is extreme, and would seem to be evidence of the far right’s argument that the left has gone beyond all decency. The use of radical tactics like doxxing, furthermore, has serious implications in an era when people are willing to go to great lengths to combat the threats that emanate from the White House and the worst of its supporters. Perhaps there are few outside the racist right who would mourn the death of Andrew Dodson, and fewer still who would argue that he deserved anonymous cover to spread racial hatred. Still, is there any resistance tactic that is out of bounds when it comes to fighting Nazi trolls? Did Andrew Dodson’s supporters, for all their hypocrisy, have a point? Or were they deliberately conflating two very different things, in an attempt to create a false moral equivalence between vicious online harassment and a powerful tool in the fight against violent racism?

The tactic of exposing people’s identities to fight racism has a precedent in the U.S. The governor of Louisiana, John Parker, suggested in a speech in 1923 that “the light of publicity” should be turned on the Ku Klux Klan: “Its members cannot stand it. Reputable businessmen, bankers, lawyers, and others numbered among its members will not continue in its fold. They cannot afford it.” Later, during the Civil Rights era, several newspapers, aided by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, printed names and ranks of local Klansmen.

But the impact was limited to local communities, where the identities of Klansmen were often common knowledge anyway. As a political tool, the publishing of private information became more potent in the 1980s and 1990s, when it was used by right-wing Christian conservatives against abortion providers. And it was thanks to the internet that doxxing, as it is now known, became widespread and devastatingly effective.

I first met Jenkins outside the CPAC convention in Washington, D.C., in 2015, where I was reporting on the nascent far-right groups that were mingling with the GOP establishment with new intimacy. Jenkins had been warning people about the far right for more than a decade. In the 1990s he was a young activist trying to figure out how to fight the forces of white supremacy in America. He wanted to expose the racists to the world, to shame them into submission. The problem was that, as an African-American, his options for doing so were limited. He couldn’t very well go undercover and report on them.

“I had the idea of publishing names and addresses after I saw anti-abortion activists doing it to abortion providers,” Jenkins told me. During the 1980s and 1990s anti-abortion activists routinely distributed the personal information of abortion providers, many of whom became targets of threats and violence. In 1997, anti-abortion activist Otis O’Neal “Neal” Horsley published the infamous “Nuremberg Files” website, a list of almost 200 active abortion providers, complete with photos, home addresses, and phone numbers. The site celebrated any act of violence against the providers and contained thinly veiled encouragements to its readers to take matters into their own hands.

Andrew Dodson at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.Arkansas Times

Andrew Dodson at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.Arkansas TimesIn 1995, Planned Parenthood sued Horsley along with the American Coalition of Life Activists, claiming that the Nuremberg Files presented a threat to the people named in them. Planned Parenthood won the case but lost on appeal, when a federal court ruled that the First Amendment protected the files. A later appeal eventually overturned that verdict, but at that point Jenkins had had an epiphany: “When abortion providers took these people to court and lost, I said, ‘OK, this is another tool we could use.’” The lesson that he took from these early anti-abortion doxxes wasn’t that releasing private information could get people killed, but rather that you could do it and get away with it. “We didn’t see it as a weapon,” he said. “We never used it as a threat. We wanted to be open about what we saw and this allowed us to be open.”

Until relatively recently, online doxxing was contained to the trenches of various culture wars in remote regions of the web. But as social media became the dominant force of life online, these disputes were opened to a wider audience. In 2011, the hacker collective Anonymous, which was then relatively unknown, released the names and addresses of several police officers who used excessive force against Occupy demonstrators in New York City. It was, in the eyes of the activists at least, a democratization of force. They were not powerless anymore.

And then came the trolls. In 2014, on the message board 4chan, users conjured a spurious set of accusations regarding computer game developer Zoe Quinn. As the made-up scandal gathered steam, Quinn was subjected to an orchestrated harassment campaign that included not only a multitude of rape and death threats, but also the publishing of her private information. Doxxing could no longer be considered merely a tool the righteous could use to expose and shame evildoers; it was available to anyone and could be used on anyone.

Doxxing, even in the most extreme cases, is fraught with ethical complications. On the one hand, those who choose to publicly take part in extreme political action accept that their identities will be public, too. It is the price of doing business, and most on the fringe right understand that. When Matthew Heimbach, the disgraced former leader of the Traditionalist Worker Party, one of the more notorious neo-Nazi groups to gain prominence in the 2016 election, slept with a loaded shotgun next to his bed, it was because having his address known by his political adversaries was a risk he had been willing to take. Heimbach was a high-profile leader in the white nationalist movement, and he and his wife had accepted the possible repercussions.

On the other hand, doxxing can be an ugly and indiscriminate weapon, even when used in the fight against white supremacy. Katherine Weiss, a low-level member of Heimbach’s group, was once doxxed. She showed me numerous texts and emails of rape and death threats. Weiss’s white supremacist views were abhorrent, but is a threat of being “raped to death” justice? The trolls and racists of the far right regularly threaten female journalists and activists with sexual violence and death—which makes it all the more sobering to see the same threats going in the other direction.

Is doxxing excusable when used against the right targets? Do the ends ever justify the means? In a ProPublica article published in the aftermath of Charlottesville, Danielle Citron, law professor at the University of Maryland, warned of the dangers of the practice. “I don’t care if it’s neo-Nazis or antifa,” she told ProPublica. “This is a very bad strategy leading to a downward spiral of depravity. It provides a permission structure to go outside the law and punish each other.”

Doxxing can be an ugly and indiscriminate weapon, even when used in the fight against white supremacy.To an extent, Jenkins agrees. “I think right now things are becoming a little dicey,” he said. “More aggressive. Nobody wants to see anybody hurt.” But he places the blame at the feet of those in power, not the doxxers: “The political process is such that you don’t really see solutions to problems. People are at a loss as to how to change society and they are lashing out.”

In the super-heated environment of the Trump era, the pool of potential doxxing targets has grown. A few weeks ago, as Donald Trump’s policy of zero tolerance on the border between the U.S. and Mexico forcibly separated thousands of children from their parents, calls went out to doxx the employees of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE). Sam Lavigne, an artist who works with data and surveillance in New York, used software to scrape the LinkedIn profiles of nearly 1,600 ICE employees. “No one really seems willing to take responsibility for what’s happening,” he told Vice. “I wanted to learn more about the individuals on the ground who are perpetrating the crisis.”

An employee of the Department of Homeland Security recently found a burnt and decapitated animal carcass on their doorstep. Jordan Peterson, the controversial conservative professor, doxxed two of his own students for organizing a protest against a right-wing free speech rally. Employees and associates of Planned Parenthood get doxxed on an almost daily basis.

Journalists are targets, too. In May, HuffPost reporter Luke O’Brien wrote a story that revealed the identity of noted racist blogger Amy Mekelburg. The harassment started even before the story was published. Under her Twitter handle @amymek, Mekelburg accused O’Brien of stalking her, using the reporter’s requests for comment as evidence that he was harassing her. Almost immediately, O’Brien and several people around the country who shared his name were set on by an army of Mekelburg’s defenders. They either did not know or care that his only crimes had been rigorous journalism and giving a very public political figure the opportunity to comment on a story about her. Violent threats started pouring in through Twitter, emails, text messages, and phone calls. Soon personal information about O’Brien’s family was published online. O’Brien spent 20-hour days gathering evidence of threats, which Twitter officials did little to combat.

Another person named Luke O’Brien, who works as a freelance defense analyst, received dozens of threats over Twitter and email. He told me that he had defended the other O’Brien—until people started showing up outside the house where he lives with his wife and child. “It was enough to poison the well and make me reconsider how I dealt with them,” he told me. “Is it really worth the safety of my family to say what I believe, which is that these people are horrible?”

Doxxing journalists is nothing new. There have been many instances of a reporter’s personal information being released, and most female journalists are well acquainted with the realities of online harassment. Over the course of tormenting O’Brien, white supremacist trolls spawned a new meme. Pictures of bricks turned up in the inboxes of journalists all over the country. On them were the words “Day of the Brick,” a reference to “Day of the Rope,” a plot point in neo-Nazi Bible The Turner Diaries, where the heroes of the book spend a day hanging lawyers, teachers, journalists, and other “traitors.” The fantasy of hanging journalists was replaced with the fantasy of smashing them with bricks. By doxxing O’Brien, the trolls meant to threaten all members of his profession.

“They don’t care who they go after, that’s part of the strategy,” O’Brien told me. “They go after everyone else until they know they have the right person.”

Few outside the outraged feedback loops of the far right would agree with O’Brien’s attackers that the aims and practices of journalism and those of doxxing are equivalent. A journalist provided, in this case, a public service by identifying dangerous white supremacists, whereas the doxxers who revealed his family’s personal information were trying to intimidate someone they considered an ideological opponent with an omnipresent threat of violence. But the conflation of genuine reporting with doxxing points to a foundational challenge in considering the issue.

“One of the problems is that not only our opinion about when doxxing is right and wrong, but also about what constitutes doxxing, often change with who is doing it,” said Steve Holmes, an assistant professor in the department of English at George Mason University who has written extensively on the ethics of doxxing. “When you support the motives behind a given doxx, it is easy to go along with it as a justifiable act.”

The far right considers the practice of releasing personal information about anti-fascist activists a useful weapon. But when a journalist like O’Brien exposes one of their own, they consider the release of personal information an inexcusable violation of privacy. Similarly, those on the left are affronted by threats against anti-fascist activists, while supporting the doxxing of ICE employees.

The best way of looking at it, according to Holmes, is on a case-by-case basis; broad conclusions should be avoided. “Perhaps we need a taxonomy of the different forms of doxxing,” he suggested. “Doxxing can be a political threat, the revenge of a jilted ex, the exposure of toxic ideologies, and it can be the act of a whistleblower. We need a way to differentiate.”

Naming white supremacists would seem to fall clearly into a category of exposing a toxic ideology. O’Brien told me that, while he was torn on doxxing as a general practice, he saw its value in exposing violent racists. “There’s a logic to it coming from antifa,” he said. “If you have a crypto-racist and fascist living next door to you, you’d probably want to know about it.” For Daryle Lamont Jenkins, a white supremacist who is active politically has forgone the right to privacy. “Until you show me a better way to defeat them, then shining a light on these people is the best thing we got,” he argued.

“When you support the motives behind a given doxx, it is easy to go along with it as a justifiable act.”Much like those who go after the worker bees of ICE, Jenkins targets the lower-level Nazis of the white supremacist movement. The leaders, he said, are public anyway. It is the foot soldiers that he believes can be scared off by the prospect of being outed. There is anecdotal evidence that supports his belief. The spotlight that was trained on the far right after Charlottesville not only caused members to leave the movement, but also led to entire groups shuttering.

“Doxxing is a major hindrance to the far right, as it is one of the main stumbling blocks to real-world organization,” said George Hawley, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Alabama who has studied the far right in America. As he sees it, the threat of exposure has taken a significant toll on the white nationalist movement. “The social consequences of being associated with one of these groups can be quite high,” he said, “and for that reason few people are willing to do more than post anonymously on the internet.”

Jenkins believes the recent successes of the doxxing campaign can be attributed to the changing nature of the far right. The current crop of white supremacists, known in the movement as “white nationalism 2.0,” are a different crowd than the 1.0 gang. “These are people who want to be in society,” he said. “They want to be doctors and politicians and police officers, and they can’t do that if they get publicly known as a Nazis. The 1.0 crowd didn’t care. They weren’t worried about getting into mainstream society.”

The 2.0 nationalists have much more to lose, but since they are part of the mainstream they are also, according to Jenkins, far more dangerous. This presents its own challenges for the doxxers of the anti-fascist movement. You can only get doxxed once; after that there is not much left to do to a person. “Doxxing has less of an effect the more committed a white supremacist you are, because you’re more likely to have already revealed your beliefs or be less troubled in having them revealed to the world,” said Mark Pitcavage, senior researcher at the Center on Extremism at the Anti-Defamation League. “It is most effective against those white supremacists, often relatively new, who worry about leaving the closet.”

Oren Segal, the director of the Center on Extremism, added that doxxing has led racist agitators to hide themselves better. “It is common to see younger white supremacists covering their faces in their propaganda these days,” he told me. “Even flash demonstrations, which are primarily a response to antifa, enable white supremacists to have greater control of the presentation of their images.”

Still,

the point of doxxing is to spread fear. Just because one doxxed nationalist has

nothing left to lose, it could still affect the choices of those who remain

anonymous. “Doxxing extends beyond hurting a particular individual,” Hawley said.

“The goal is to make an example out of someone, to show others what can happen

if they sign up with the radical right.”

In this respect doxxing, for all its complications, has undeniable upsides. Pointing out that people on both the far left and the far right utilize doxxing creates a false equivalency, rooted in the notion, made famous by Donald Trump after Charlottesville, that “there are good people on both sides.” The threats of violence leveled at female, Jewish, and African-American journalists and activists are not matched by anything experienced by white people on the fringe right. The orchestrated efforts of that cohort to harass and threaten those with whom they disagree or simply dislike are unrivaled by anyone else, as is their blanket encouragement of violence against reporters.

But there is political expediency in lumping the two sides together as equal combatants. The disruptive protests by the Black Bloc faction of antifa during Trump’s inauguration, their brawls with fascists on the streets of many American cities, and their efforts to shut down speaking engagements of far-right speakers, have led conservatives in Congress to realize that there is political hay to be made. To that end, Rep. Dan Donovan of New York came up with HR 6054, also known as the “Unmasking Antifa Act.” The law aims to target anyone who “injures, oppresses, threatens, or intimidates” those exercising a constitutional right, but is widely seen as an attempt to cast antifa and other left-wing protesters as a threat to public safety, ignoring the fact that far-right activists have a far bloodier track record, not just in recent times, but also throughout the last century. In fact, 18 states already have anti-mask laws, enacted in response to KKK violence during the Civil Rights era.

The bill, designed to equate the far right and the far left, is of a piece with far right joining Andrew Dodson’s death to their cause. It is a tool used to validate the assertion that leftists are a violent mob out for blood, that their version of rough justice is completely depraved. These are polarized times, but justice is not simply in the eye of the beholder—at least not yet.

Deborah Levy’s new memoir The Cost of Living opens with an epigraph by Marguerite Duras: “You’re always more unreal to yourself than other people are.” Yet when Levy, at 50, decides to separate from her husband after 20 years of marriage, she suddenly begins to feel more real than before. Her life speeds up and becomes chaotic. Dismantling “The Family Home” she shared with her husband and two daughters has made her confront what she termed in the title of her first memoir Things I Don’t Want to Know—who she is, and how she and the other mothers on the playground had “metamorphosed” into “shadows of our former selves, chased by the women we used to be before we had children.” She finds she is able to work surprisingly well in this chaos. The ideal of enduring love in marriage, she decides, may have been a “phantom” all along.

THE COST OF LIVING: A WORKING AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Deborah LevyBloomsbury Publishing, 144 pp., $20.00

THE COST OF LIVING: A WORKING AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Deborah LevyBloomsbury Publishing, 144 pp., $20.00With her heterosexual, nuclear family, Levy had built her life around “the story the old patriarchy has designed.” The Cost of Living chronicles her attempt to redraft that story. The author of six novels—including two nominated for the Man Booker Prize, as well as plays produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and the BBC—poems, stories, and a libretto, Levy characterizes her life as a long process of learning to use her voice. In Things I Don’t Want to Know, she relates her childhood in South Africa, focusing on the year she was “practically mute” after her father was imprisoned for opposing apartheid, and her adolescence in England, where she scribbled on napkins in greasy spoons to mimic what she thought writers did. That book also foreshadows her unraveling as an adult: Unable to stop herself from crying on escalators, she realizes something has to change when she misreads a poster on “The Skeletal System” as “The Societal System.”

Like the recently liberated Levy herself—who appears in The Cost of Living covered in grease, biking up a treacherous hill on her new electric bicycle, writing in a shed owned by an octogenarian friend, and performing minor feats of plumbing while wearing a black silk nightdress and thick utilitarian postman’s jacket—many of the scenes and observations in The Cost of Living do a lot of work, mostly on behalf of feminist arguments. Early on, Levy describes a man whose husband has died as crying “like a woman”: “He did not so much cry as wail, sob and weep; his tears were very strong…It was a very expressed grief.” This is how she cried when she realized her marriage was over, but she’s never seen a woman cry like a man. She sees signs everywhere, all pointing to The Societal System.

Levy’s project can be read as a kind of foil to Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, which also takes the woman writer as its subject. Whereas Cusk subtracts her narrator, Levy adds more and more of hers, but both are concerned with devising new ways for women to work around the structures imposed on them, as narrators, writers, and people in the world. For female writers, the first person can be difficult—if you don’t wield it like a weapon it could hurt you. Speaking to a woman named Gupta about her malfunctioning Microsoft Word program, Levy notices the I in a chat box “blinking and jumping and trembling.” She feels like that, too. Later she describes a young woman on a train as having “very expressed hair,” blue braids secured with rosebud bands. This statement seems to act as a sort of compensation for the girl’s inability to use her voice: On the train, an older man takes up all the space on the group’s shared table and blathers on about his concerns about refugees, preventing the young woman from studying French on her laptop.

For female writers, the first person can be difficult—if you don’t wield it like a weapon it could hurt you.Levy keeps meeting stereotypical sexists like this, men who ignore or talk over young women, and who won’t refer to their wives by their names. As retribution, the only men she names in the book are dead writers—like James Baldwin, Proust, and Nelson Algren, who wanted his lover Simone de Beauvoir to leave Paris and move to Chicago to be with him, in a house, perhaps with a child. De Beauvoir, who like Levy in her French slip and postman’s jacket wanted “everything from life…to be a woman and to be a man,” refused. She doubted she could write at the same time as settling into domesticity. Levy adds: “I had found it quite tricky myself.”

Life without love is a “risk-free life,” and a “waste of time,” but within our societal system, to be a woman who cares about her work in a relationship with a man is difficult, if not impossible: “Women are not supposed to eclipse men in a world in which success and power are marked out for them.” Assuming the role of wife, or even girlfriend, means accepting the stability of the existing structure and sacrificing one’s essentially “chaotic” desires. That’s an especially big risk for a writer—you could lose yourself, and your voice.

It’s taken Levy much longer than de Beauvoir to realize that under patriarchy, as the refrain goes, women can’t have it all. (To be fair to Levy, de Beauvoir also had the advantage of falling in love with one of the few men in the world who would go for the radical non-monogamous intellectual commitment she wanted, especially in the 1950s.) She starts to conceive of herself as a kind of mentor for the younger generation. “The right reader” for her story, she discloses at the beginning of the book, is a young woman she overhears having a frustrating conversation with a dismissive older man. She also brings a writing student to tears by telling her she is talented; the student has made edits that allow her to “own up to” the “force” of her voice. “It is so hard to claim our desires,” Levy reflects, “and so much more relaxing to mock them.”

This wisdom, however, could cut two ways. Levy, with her critique of domestic femininity “as written by men and performed by women,” has one set of desires. But what about the many women who desire to be beautiful, so much that they spend thousands of dollars on clothes and skincare products they cannot really afford? What about those who want nothing more than to get married and have children and cook dinner in a nice big house they’ve decorated? Sometimes our desires are absurd, the most intense ones inspired by the systems we actively try to resist and overthrow. The script is repetitive and tired, circling back on itself. What can we do but laugh about that?

Lines like the one I’ve quoted above are not entirely representative of Levy’s style—she’s a master of puns and pithy, surprising twists, often deployed at her own expense, though she finds it difficult to let funny accidents or coincidences be merely what they are. At one point she ill-advisedly rides her beloved e-bike up a hill in the pouring rain and her bag splits open, sending the chicken she’s just bought to cook for dinner into traffic; a car runs it over. Most people would consider this a hopeless situation and not cook the chicken. Levy turns it into a moment for reflection on the ironies of life as a “free” woman: She is “Free to pay the immense service charges for an apartment that had very little service…Free to support my family by writing on a computer that was about to die.” Then she cooks the chicken—leaving out her recently purchased rosemary, “the herb for remembrance,” which she’d planted in the family garden long ago; all she wants to do is forget—and has a small dinner party with her daughter and her teenage friends. “I thought they could save the world. Everything else fell away, like the flesh from the run-over chicken, which…[we] devoured with relish.”

She’s taking what she’s got and going with it, as in her writing, which riffs on seemingly random images and ideas, creating connections that make these short books feel holistic and sweeping. She uses motifs, such as roses and footsteps, like landmarks on a map, which are useful signposts in her frequently disorienting story. She takes one chapter title, “X is where I am,” from a postcard her mother sent her from South Africa, and writes, “I lost all sense of geographical direction for a few weeks after my mother’s death…Her body was my first landmearc,” the Old English word she thinks of while her clueless taxi driver is trying to get her where she needs to go. Using his GPS, totally lacking a sense of the city beyond the digital map that tells him what to do, he is “absent to its physical presence, and instead was existentially alone but together with his satnav.” Which is also what her marriage was like.

Aphorisms that would usually be heavy-handed breeze past; only later do you realize you’ve been self-helped.It’s a testament to Levy’s light touch and originality elsewhere that her feminist epiphanies and extended metaphors—life is a tempest, a book or film in which she is trying to conceive of herself as a major character, and a journey—don’t immediately register as cliché. With the help of a quote from Elena Ferrante, she determines that “The process of restoration, the bringing back and repairing of something that existed before”—here she’s talking about her run-down art deco apartment building—“was the wrong metaphor for this time in my life. I did not wish to restore the past.” She paints her walls yellow and finds it disturbing, enacting implied and explicit references to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” She eventually paints all the walls except one white again. Aphorisms that would usually be heavy-handed (“If we cannot at least imagine we are free, we are living a life that is wrong for us”) also breeze past; only later do you realize you’ve been self-helped.

It’s often as if Levy is trying to become the writers she cites, using them as guides through the “black and bluish darkness,” a phrase she uses as a chapter title and later reveals she’s borrowed from an interview with a Mexican woman who crossed the border into America alone, at night. “When a woman has to find a new way of living and breaks from the societal story that has erased her name, she is expected to be viciously self-hating, crazed with suffering, tearful with remorse,” Levy writes. “These are the jewels reserved for her in the patriarchy’s crown…it is better to walk through the black and bluish darkness than reach for those worthless jewels.” This inspirational pronouncement—that jewels are worthless—demonstrates the limits of Levy’s mode of metaphor-making. According to Levy, the Mexican woman she quotes had seven children and worked as a dishwasher in a Vegas casino. I wonder if she can at least imagine she’s free.

No comments :

Post a Comment