President Donald Trump’s announcement on Monday night that he would appoint Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court marked the culmination of a decades-long conservative campaign to reshape the federal judiciary. Sandra Day O’Connor, David Souter, and Anthony Kennedy can no longer disappoint the Republicans who helped place them on the bench. The high court’s future—and the nation’s—is now in the hands of a reliable majority of five conservative justices.

“Judge Kavanaugh has impeccable credentials, unsurpassed qualifications and a proven commitment to equal justice under the law,” Trump told a White House audience. Kavanaugh thanked Trump for his decision and pledged his fidelity to the nation’s constitutional order, telling the audience that judges “must interpret the law, not make the law.”

There’s always a chance that Kavanaugh’s nomination will fail in the Senate, but the GOP’s majority in the chamber there makes it unlikely. Filling the nation’s courts with conservative justices is a unifying principle for the Republican Party and appears to be the one sacred cow that even Trump won’t slaughter. Democrats, by comparison, have never made the court’s future a make-or-break issue for its base. Trump’s choice of Kavanaugh could change that.

In 2005, then-Senator Joe Biden described the process to confirm a potential Supreme Court justice as a “Kabuki dance.” His description is even more apt today. The elaborate theatricality hasn’t changed much in the intervening years: Senate Democrats will once again try their best to get the nominee to share his views on abortion, LGBT rights, and other major issues while Kavanaugh plays coy and declines to signal how he would rule on future cases.

Much of the credit for the American right’s victory on Monday goes to Leonard Leo, a highly influential figure in the Federalist Society, the flagship of the conservative legal movement. (Leo is currently on leave from the group while the confirmation process unfolds.) Three of the court’s current justices—John Roberts, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch—can trace their appointments to his influence. Gorsuch and Kavanaugh were both on a list of 25 potential nominees that Leo vetted for Trump in 2016.

Of course, Republicans rarely acknowledge the goals of this long legal campaign. Leo gave an excellent opening performance last weekend to ABC’s George Stephanopoulos. “Is it fair to say that anyone who made it onto your list is likely to be an opponent of Roe v. Wade?” Stephanopoulos asked him, citing warnings by abortion-rights groups. “Nobody really knows,” Leo replied. “I think it’s a bit of a scare tactic and rank speculation more than anything else.”

This is a polite elision at best. Trump himself said during the 2016 presidential debates that he would appoint “pro-life justices” who would eventually overturn Roe. Whether Kavanaugh would do so won’t be known for some time, but his staunchly conservative record, and his promotion by the Federalist Society, suggests he would.

Kavanaugh, 53, is a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, an influential bench that reviews federal cases from the nation’s capital. The court’s docket is filled with cases involving the myriad government departments and agencies that are headquarted in Washington. From there, Kavanaugh has carved out an aggressive record when it comes to limiting the powers and functions exercised by federal agencies.

Federal courts typically rely on what’s known as the Chevron doctrine—named for a 1984 Supreme Court case involving the oil company—to determine whether an agency’s rule or regulation conforms to laws passed by Congress. Under the doctrine, courts must generally defer to an agency’s own interpretation of federal statutes when hearing challenges to that agency’s exercise of power. Many conservative legal experts and some Supreme Court justices are hostile to the Chevron doctrine on separation-of-powers grounds, believing that it grants too much leeway to federal officials. That hostility also often reflects a deeper aversion to the government’s regulatory powers.

In a Harvard Law Review article in 2016, Kavanaugh described the doctrine as “nothing more than a judicially orchestrated shift of power from Congress to the Executive Branch,” suggesting he may be open to curbing or overturning Chevron if confirmed. He also wrote a lengthy opinion in 2016 in which he found the leadership structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a frequent target of conservative opprobrium, to be an unconstitutional violation of the president’s control over the executive branch.

Many of Kavanaugh’s other rulings will spark delight among conservatives and dismay among liberals. In 2011, he dissented from a D.C. Circuit ruling that upheld the District of Columbia’s ban on automatic weapons, urging his colleagues to take a less lenient approach when weighing whether gun restrictions passed muster under the Second Amendment. While the D.C. Circuit rarely hears abortion cases, Kavanaugh sided with the Trump administration last year in a ruling to block an undocumented immigrant teenager from obtaining an abortion while in federal custody.

Trump may have also been drawn to Kavanaugh’s expansive view of executive power in other areas. In a 2009 article for the Minnesota Law Review, the judge strenuously argued against prosecuting or suing a sitting president—an issue near and dear to Trump’s heart, as special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian electoral meddling looms over his presidency.

“In short, the Constitution establishes a clear mechanism to deter executive malfeasance; we should not burden a sitting President with civil suits, criminal investigations, or criminal prosecutions,” Kavanaugh wrote. “The President’s job is difficult enough as is. And the country loses when the President’s focus is distracted by the burdens of civil litigation or criminal investigation and possible prosecution.”

Democrats, on their own, have no way to prevent Kavanaugh from taking a seat on the Supreme Court. Nonetheless, his confirmation process could face pitfalls. Republicans currently hold 51 seats in the Senate. With Arizona Senator John McCain absent from Washington while he undergoes treatment for brain cancer, the GOP can only afford to lose one vote. Maine’s Susan Collins said last week she won’t support a nominee who “demonstrated hostility” to Roe, though Kavanaugh is extremely unlikely to do that in his confirmation hearings.

Republican voters may tolerate many heresies from their elected officials, but refusing to back a conservative Supreme Court justice isn’t likely to be one of them. Exit polls from the 2016 election found that a quarter of Trump voters cited the Supreme Court as their reason for voting for him. The prospect of Hillary Clinton appointing Antonin Scalia’s replacement, after the justice died in early 2016, also helped solidify Trump’s standing among top conservatives.

Democratic leaders, by contrast, haven’t made the high court’s future into a core issue in their political campaigns. Clinton and Barack Obama declined in 2016 to make the case for building the court’s first liberal majority since the 1960s. Instead, Democrats opted to make normative arguments about the impropriety of Mitch McConnell’s role in blocking Merrick Garland—the widely respected moderate whom Obama nominated to replace Scalia—and the Senate confirmation process itself.

The conservative movement’s push to remake the courts since the 1970s and 1980s ultimately sprang from the Warren Court’s spree of liberal decisions in the 1950s and 1960s. Now that conservatives firmly control the court’s direction, their rulings may prompt a similar pushback from liberals in the years to come. Monday’s announcement may ultimately mark not just the culmination of one campaign for control of the nation’s judiciary, but the beginning of another.

It is not normal to see “race against time” and “ship laden with soybeans” in the same sentence, but last week a cargo ship carrying soybeans to China found itself in the trade equivalent of Smokey and the Bandit. Hoping to beat a 25 percent tariff that China was about to levy on U.S. soybeans, the Peak Pegasus dashed across the Pacific. But it ultimately fell short of its goal, Bloomberg reported on Friday morning, arriving in China hours after the new tariffs went into effect.

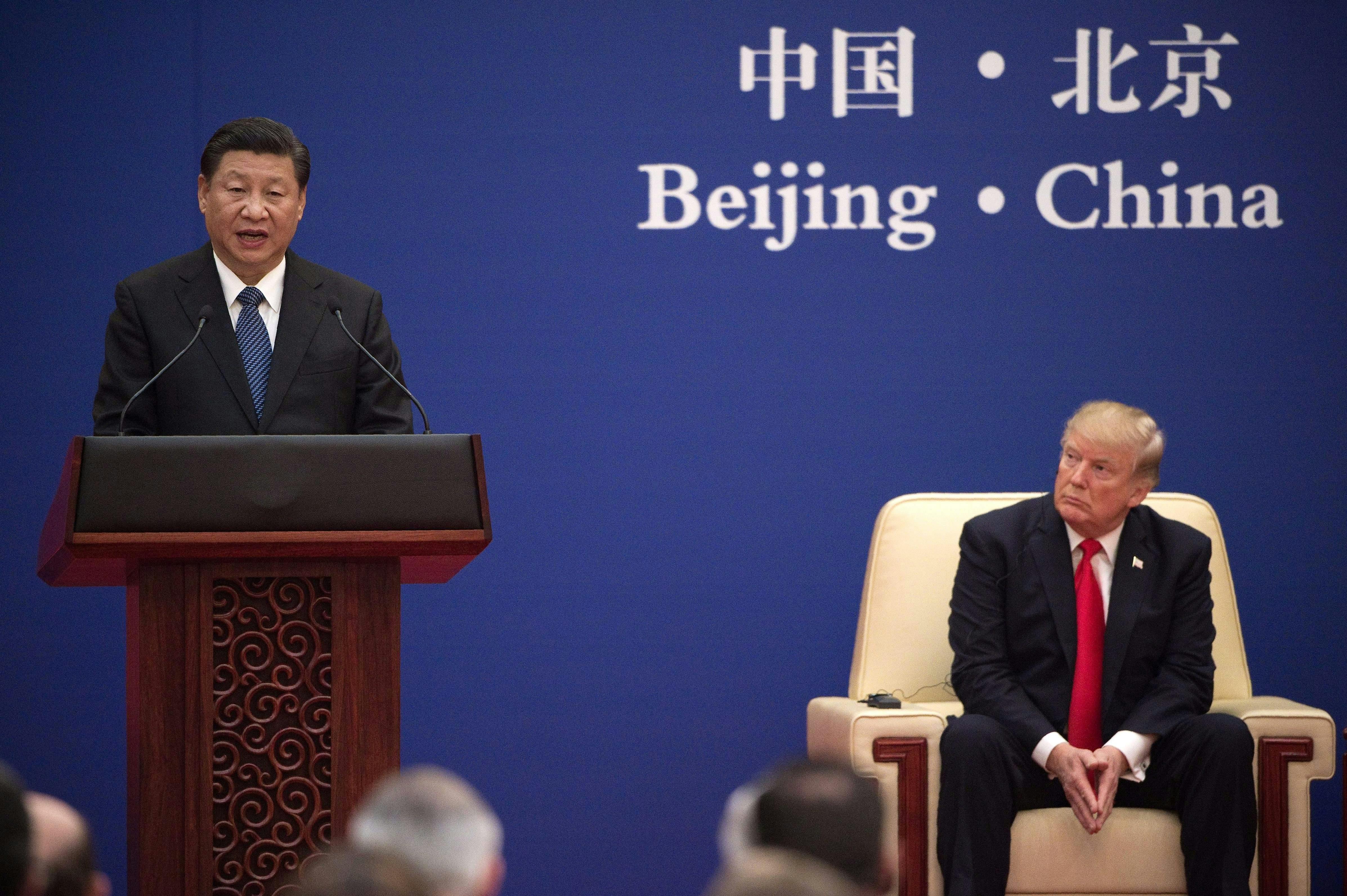

The voyage of the Peak Pegasus lent an absurd but fitting tinge to the beginning of what could be a very serious trade war between the United States and China. After initiating $34 billion in tariffs on Friday, the Trump administration is poised to impose an additional $16 billion in two weeks. All in all, President Trump has threatened to levy up to $500 billion if China doesn’t change its behavior toward American companies.

But beyond that demand, it’s unclear what this trade war is meant to accomplish—or what the Trump administration would ask for if China and the United States were to agree to come to the negotiating table. Instead, the administration has entered into a high-stakes gambit with neither a strategy nor an off-ramp in sight for either nation, which has turned the standoff into a microcosm of the administration’s blunt, simplistic approach to policy. In this case, it’s one that could easily backfire.

In August of 2017, the Trump administration announced it was launching an investigation into China’s treatment of U.S. companies. This investigation found what has been widely known for some time: that China not only forces a number of foreign companies to partner with Chinese companies in order to do business in the country, but also requires those foreign companies to hand over intellectual property, including proprietary information, to the Chinese companies.

Operating in China is thus a double-edged sword. Because of its size, it is a crucial market for many large companies, but gaining access to that market often requires them to yield their most valuable intellectual property and trade secrets. This has been a longstanding problem for U.S. leaders of both parties.

Most recently, Barack Obama pushed the Chinese government on these issues and its manipulation of its currency. “The key with China is to continue to simply press them on those areas where trade is imbalanced, whether it’s on their currency practices, whether it’s on IP (intellectual property) protection, whether it’s on their state-owned enterprises,” he said ahead of trade talks in late 2014. In 2015, the Obama administration and the Chinese agreed to not steal trade secrets for the benefit of domestic companies. While the Trump administration has jettisoned a number of Obama-era deals, it has stuck with this agreement.

What’s most notable about the Trump administration’s tariffs is its decision to go it alone and bypass other potential avenues, like the World Trade Organization. While the administration did file a complaint against China in mid-March, the taxes it placed on Chinese goods violate the rules of the WTO, which was created, in part, to prevent costly and unnecessary trade wars like the one that is currently brewing. The United States, moreover, has done very well in WTO disputes, winning its cases over 80 percent of the time. While it seems unlikely that WTO arbitration would suddenly cause China to start playing by the rules, there’s no reason to believe that a trade war will be any more successful.

The administration’s decision to ignore the WTO, which it has spent the past months undercutting, follows a long pattern of unilateral action, from the administration’s decision to bomb Syria in April of 2018 to the president’s decision to “rip up” the Iran nuclear deal to his recent spat with European leaders Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron.

It also follows another pattern, that of Trump placing an extreme and unearned level of confidence in his own power as a negotiator—which was present in both the administration’s failed push to repeal Obamacare and, more recently, its denuclearization talks with North Korea. In this instance, Trump seems to believe that fear of economic retaliation will be enough to get the Chinese to come crawling to the negotiating table, where he will have all the leverage. But that’s the sum total of the strategy: There seems to be no plan besides the unwavering belief that escalating economic pressure will eventually break the Chinese.

The problem is that the Chinese economy is large enough to withstand the pressure. Furthermore, its leaders are less encumbered by particular constituents who may be harmed by a trade tit-for-tat, whereas Trump is already being subjected to criticisms from industry and voters. For now, both the U.S. and China are convinced that the other will blink as soon as the political and economic costs are felt.

Trump’s recent work as a negotiator indicates where this dispute might be heading. Over the course of the last 18 months, he has often ratcheted up political and economic pressure before accepting a symbolic resolution, such as in his dealings with North Korea. This is a volatile, risky strategy, but the impulse towards face-saving is reassuring. It’s possible that some arrangement could be reached wherein China agrees to stop harming U.S. companies and, in exchange, the administration lifts its tariffs on Chinese goods, before relations revert back to the status quo. Given that Chinese actions are hurting U.S. companies, this is not a very good outcome for the United States, but it’s still better than a harmful, protracted trade war.

For now, none of this is a very big deal—unless you’re a soybean farmer or a lobsterman, two American constituencies that have been hit hard. Combined, the economies of the United States and China are over $30 trillion. In the big picture, $34 billion in new tariffs is not very large at all. It will still be months until this trade war is felt by consumers, although the political impact in agricultural states—many of which voted for Donald Trump in 2016—may be felt sooner. What’s worrying is that Trump is willing to gamble with people’s livelihoods to play what amounts to a big game of chicken, which means an escalation may be inevitable.

E. coli bacteria entered the public imagination in 1993, when Jack in the Box, a West Coast fast food chain, was the source of the most infamous food poisoning outbreak in modern American history. Beef patties contaminated with Escherichia coli O157—one of the deadliest types of E. coli pathogens—were found to have been sold at 73 of the restaurants across the country. More than 700 people were infected, 179 were left with permanent brain and kidney damage, and four children died. The last one to die was Darin Detwiler’s 17-month-old son, Riley.

Today, Detwiler is one of America’s leading food safety advocates, and a professor of food policy at Northeastern University. This week, he’ll be receiving Food Safety Magazine’s Distinguished Service Award—a bright spot in a career birthed by tragedy. It would be a more satisfying honor, though, if the United States weren’t currently dealing with yet another deadly outbreak of E. coli O157, he told me by phone last week. “It’s as if my son were killed by a drunk driver, and I turn on the news and hear about another one on the road,” he said. “It’s like a knife in my back every time.”

On April 10, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned against eating any romaine lettuce from anywhere in the country, fearing it might be contaminated with E. coli. At that point, 17 people had been reported ill, and six had been hospitalized. Three days later, the agency identified chopped bag lettuce from the Yuma, Arizona, region as the most likely source. Some companies issued voluntary recalls of their products, but the Food and Drug Administration refrained from issuing mandatory recalls, because they couldn’t find the exact source of contamination. The CDC’s warning remained in effect until June 28, when the agency said tainted lettuce from Yuma “should no longer be available.” In that update, the CDC said 210 people across 36 states were sickened by E. coli O157, and five people died, making it the worst outbreak in more than a decade.

The CDC’s green light to eat romaine again may have marked the end of the lettuce crisis in consumers’ minds, but the situation is far from over. The agency and the FDA are still investigating why and how a dangerous strand of E. coli wound up contaminating lettuce in Yuma. No single grower, harvester, processor, or distributor has been blamed, and investigators are still unsure whether contamination happened during the growing, washing, chopping, or bagging process. So far, the agencies have only released one finding: That the same E. coli strain found in sickened people across the country was also in Arizona’s canal water, which is used to irrigate crops.

This outbreak thus should not be seen only as a food poisoning outbreak, but a major water contamination crisis—the worst since Flint, Michigan. The agency’s finding also raises questions that Detwiler and other E. coli experts say more people should be asking, such as: How did deadly bacteria end up in crop water? And why does it keep happening in a country that’s supposed to have some of the strongest environmental protections in the world?

Escherichia coli is a naturally-occurring, but sometimes dangerous bacterium that lives in the intestines of animals, which is a polite way of saying it’s found in poop. The strain implicated in both the Jack in the Box and romaine outbreaks, O157, is called a “Shiga-toxin producing” strain, which can cause kidney failure and lead to death, particularly in vulnerable populations like children and the elderly.

O157 is among the most potent Shiga-toxin producing strains, according to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill biologist Rachel Noble. “It takes only 100 cells of E. coli 0157 to make you sick,” she said, noting that it takes 5,000 to 10,000 cells of Salmonella bacteria to do the same. O157 is also most commonly found in the fecal matter of cattle, a fact Noble says is essential to figuring out the mystery of how it got into Arizona’s irrigation canals. “There are certain cows that we call ‘super-shedders,’ whose poop contains a ton of these organisms and we don’t know why,” she said. It’s therefore possible that manure from one of Yuma County’s many livestock operations ran off into the canals that fuel Arizona’s agricultural system.

An irrigation canal and valve outside Phoenix, Arizona.toolkit.climate.gov

An irrigation canal and valve outside Phoenix, Arizona.toolkit.climate.gov“If that material goes into an irrigation canal, it’s protected by all the things that would kill the bacteria,” Noble said. “It’s staying wet, it’s not exposed to sunlight.... If the water is moving along, being used through the ditches that run through the farms and then sprayed onto the lettuce, it becomes a problem.”

Government officials investigating the case aren’t yet ready to say that’s what happened. “More work needs to be done to determine just how and why this strain of E. coli O157 could have gotten into this body of water and how that led to contamination of romaine lettuce from multiple farms,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said in a statement. The culprit could have been another animal’s fecal matter; it’s possible that humans relieved themselves in the canals. “More likely, it’s an open body of water, meaning animals can fly across it, drink from it, defecate in it,” Detwiler said.

But Detwiler thinks it’s less important where the poop came from than why the contaminated water was used on lettuce in the first place. “The liability issue comes down to, if you’re using a source of water like that, and you’re not monitoring and testing it. That’s where the problem lies,” he said. “It is such a mystery as to who exactly is supposed to be monitoring the water used to clean and water crops.”

Up until very recently, Detwiler said, there were no federal regulations requiring growers to test the quality of water used on produce—those requirements were left up to state and local governments. But the public started questioning that practice in 2006, after yet another deadly outbreak of E. coli O157, on fresh spinach. Like the romaine outbreak, the source of contamination was water pollution, traced to cattle fields near the spinach fields. The 2006 outbreak resulted in at least 199 infections across 26 states, and three people died.

After that, the industry developed the Leafy Green Marketing Association, to start training growers on the best hand-washing and anti-contamination practices. And in 2011, President Barack Obama signed the Food Safety Modernization Act into law, compelling the FDA to develop regulations for water safety on produce. It took four years after that, however, for the FDA to enact the regulations—and they only require very large farms, rather than all farms, to sample and test the water used to grow and clean produce. Today, those regulations are still being phased in—meaning some farms have started monitoring programs, and others have not. No farms are required to report their data to the FDA until next year.

While the LGMA insists its member growers go above and beyond to ensure water safety regardless of regulations, Detwiler believes that’s not the case. “Do you know how many corporate officers have gone to prison for flouting health and safety rules that led to people’s deaths?” he asked. “Three—and the largest sentence ever handed down was three months.” That’s why Detwiler believes farmers don’t have enough incentive to ensure water safety. “If I’m a farm owner, I ask myself: Do I pay to have a third party lab to test these water samples on a regular basis for me to use this water? Or do I consider the small likelihood of someone being able to tie the problem back to me, and decide against it?”

Noble, the UNC biologist, is less convinced that farmers aren’t doing their part. “Most of the farms I’m aware of belong to [LGMA], and they’re interested in being proactive,” she said. The real problem, she said, is the effectiveness of most E. coli tests. “They’re only measuring for E. coli total, not the specific types of E. coli that can make you sick,” she said. “Because their data is total E. coli, they may not have known that there was a presence of E. coli O157 in the water.”

Whether the ultimate culprit winds up being inadequate E. coli tests, weak regulations, or industry bad actors, Detwiler said the romaine outbreak should be a wake-up call that not enough has been done to prevent deadly food-borne illness. “We haven’t learned our lessons,” he said. “It’s really sad that we’re at a time when we’ve just started implementing the Food Safety Modernization Act, there’s so much doubt cast upon science and regulations, because those are the things that are going to solve this problem.”

Once the FDA and CDC complete their investigation, Detwiler hopes the public will start demanding solutions to prevent future E. coli water contamination events. “Once you’re infected, there’s no do-over,” he said. “Believe me.”

No comments :

Post a Comment