For all the talk of 2018 being the year of big tech’s reckoning, companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon have gotten off easy. Yes, formerly sky-high public approval ratings are dipping, and representatives from Silicon Valley’s largest companies—including Mark Zuckerberg—have been publicly scolded in Washington, D.C. But despite growing concerns about tech’s economic and cultural power, rampant privacy violations, and general lack of oversight, the U.S. government has been all bark, no bite.

On Monday, we got a glimpse of what meaningful action could look like: a short paper from Virginia Senator Mark Warner’s office featuring 20 “potential policy proposals” for regulating tech companies, on issues ranging from national security to fair competition to consumer protection. It’s a crucial and belated first step for Democratic lawmakers, who have been long on complaints and short on solutions, but it also shows just how far Congress is from taking legislative action—and how complicated and politically fraught passing any regulation, let alone 20 separate ones, will be.

The policy paper is, in many ways, the inverse of Zuckerberg’s appearance before the Senate Commerce and Judiciary committees in April. That hearing, on “Facebook, Social Media Privacy, and the Use and Abuse of Data,” was something of a charade. When the Facebook founder wasn’t being interrogated about unrelated matters, like his platform’s supposed suppression of conservatives, he came across like a grandson patiently explaining the internet to his confused grandparents. Even those senators who used their time to discuss possible regulations seemed out of their depth.

Warner’s paper, by contrast, is a reminder that Senate staffers often know a lot more than their bosses (though Warner, a former tech executive, is presumably an exception on this issue). The document is careful; it never entertains the possibility of breaking up the big tech companies. The proposed regulations are sensible and, for the most part, not particularly radical. But they would go a long way to simultaneously protect consumers from exploitation and protect American democracy from foreign interference.

The paper considers how to hold tech companies accountable for policing their platforms and for ensuring that hostile actors are swiftly removed. It proposes that Facebook and others have a “duty to identify” and curtail inauthentic accounts, and to report regularly to the SEC on the percentage of such accounts. The paper admits that this is a tricky one: weeding out fake accounts may require stricter identity verification requirements, “at the cost of user privacy.” It also notes that a distinction would need to be made between malicious inauthentic accounts and those that are “clearly set up for satire.”

The most intriguing idea, when it comes to enforcement, is the potential for making companies legally liable for “defamation, invasion of privacy, false light, and public disclosure of private facts,” which could lead to millions in judgments against these companies. While a “duty to identify” would likely only act as a nudge—and one that might not be entirely necessary given that Facebook and Twitter are now publicizing the mass deletion of fake accounts and the discovery of political influence campaigns—liability would go much further.

The focus on disinformation, though important, is also backward-looking and may focus too strongly on the ways in which platforms were weaponized in 2016. Disinformation campaigns are clearly changing and growing more sophisticated. Facebook announced it had discovered one on Tuesday afternoon but was unable to determine its source, which stands in contrast to the Keystone Cops nature of Russia’s 2016 activities, when it paid for advertising campaigns in roubles. That said, it’s not entirely clear what forward-looking regulation on this front would look like, though the 2018 midterm elections will likely give us a glimpse into the ways in which influence campaigns have evolved.

Aside from the threat to open up tech companies to lawsuits, the most sweeping proposals are ones that have been bandied about for some time: the adoption of privacy regulations similar to those that went into effect in the European Union earlier this year, and the passage of the Honest Ads Act, which would regulate online political advertising. Giving consumers control over their data, a la the EU’s recently enacted General Data Protection Regulation, would do much to prevent Cambridge Analytica–style abuses. The Warner proposal would force tech companies to acquire a consumer’s “informed consent” before collecting their data and would require companies to notify the public within 72 hours if a breach were to occur. The Honest Ads Act, meanwhile, would require that political advertisements on social media be subject to the same disclosures as those on television and radio.

The easiest way to achieve many of the proposals in the Warner paper would be to expand the authority of the Federal Trade Commission—which itself is one of the 20 ideas listed. The FTC lacks the “general rulemaking authority” to do very much when it comes to data protection or privacy. But that’s unlikely to change in the near term, the paper notes, as Republicans have blocked efforts to expand the FTC’s power.

That raises the biggest question with these proposals: whether they stand a chance of ever becoming law. An omnibus bill encompassing many different regulations, including those proposed by Warner’s office, would be ideal. In one fell swoop, it would bring the law up to speed with the digital age, while also implementing a holistic approach to tech regulation. But given the dynamics in Congress today, passing even just one simple regulation is challenging enough. Large-scale action seems impossibly fraught—too politically risky, and too legislatively complex.

And yet, these hurdles are a major reason why Congress hasn’t done anything concrete about big tech (the other major reason being the companies’ growing lobbying efforts). That’s why Warner’s office put out this policy blueprint. “The hope is that the ideas enclosed here,” the introduction reads, “stir the pot and spark a wider discussion—among policymakers, stakeholders, and civil-society groups—on the appropriate trajectory of technology policy in the coming years.” More likely, the paper will be debated by those who already care about the issue, and ignored by most of Capitol Hill. If the Russian influence campaign of 2016 and the Cambridge Analytica scandal led only to Zuckerberg’s wrist-slapping, one wonders what kind of calamity it will take to get Congress to deal with big tech.

One of the richest, most powerful forces in Republican politics has grown disappointed with the return on its investment. On Sunday, billionaire oil mogul Charles Koch said he regretted his vast political network’s past support of some GOP candidates who, since taking office, have not lived up to his libertarian ideals. “They say they’re going to be for these principles that we espouse and then they aren’t,” the 82-year-old told reporters at a three-day donor conference in Colorado. “So, we’re going to be much stricter,” he added. “We’re going to more directly deal with that and hold people responsible for these commitments.”

But Koch also said he would be “happy” to work with Democratic candidates who shared his values. “I don’t care what initials are in front or after somebody’s name,” he said.

The announcement marks a significant shift for the Koch network, which includes influential groups like Americans for Prosperity and the American Legislative Exchange Council. In January, it “pledged to invest more money in this midterm election cycle than any before, as much as $400 million, to support its policy objectives and help defend Republican majorities,” according to CNN. Now, “the network might now be less invested in the outcome of this election cycle. When asked Sunday whether the network would be comfortable with a Democratic majority in the House, Charles Koch suggested it would not matter to him what party controls Congress.”

The Koch network supports free trade and advocates for small government, so its lists of complaints include Trump’s trade war and a $1.3 trillion government spending bill, that adds $400 billion to the budget through 2019. On Tuesday, Trump, who was rebuffed by the Kochs in 2016, snapped at the “Koch Brothers” on Twitter, calling them a “total joke.” (Charles’s brother, David, stepped down from both the family business and political network earlier this year, prompting a rebranding away from “Koch Brothers.”)

The globalist Koch Brothers, who have become a total joke in real Republican circles, are against Strong Borders and Powerful Trade. I never sought their support because I don’t need their money or bad ideas. They love my Tax & Regulation Cuts, Judicial picks & more. I made.....

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 31, 2018....them richer. Their network is highly overrated, I have beaten them at every turn. They want to protect their companies outside the U.S. from being taxed, I’m for America First & the American Worker - a puppet for no one. Two nice guys with bad ideas. Make America Great Again!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 31, 2018“I know this is uncomfortable. It was uncomfortable for me, too,” Emily Seidel, Americans for Prosperity’s chief executive, said on a Sunday phone call with donors. “The fact that we’re willing to do this during an election year shows everyone that we’re dead serious.”

Dead serious, that is, about promoting the Kochs’ values. But what are these values, exactly, and is it reasonable to expect any modern Democrat to share them?

The political ideology of America’s second-richest family originated with the late Fred Koch. The family patriarch and founder of Koch Industries “was extraordinarily fearful of our government becoming much more socialistic and domineering,” David Koch explained to the Wichita Eagle in 2012. Fred feared a big government would hurt the family business, today the second-largest privately-held company in America. Koch Industries started as a crude oil company and became a manufacturing behemoth with subsidiaries involved in everything from oil refining to chemical production to commodities trading. Charles Koch is the chairman and CEO.

In theory, the Koch values amount to textbook libertarianism: “Lower taxes, less government regulation and economic prosperity for all,” as Americans for Prosperity puts it. In practice, however, their agenda has a hand in some of the most consequential policies in American society.

The Republican Party’s widespread denial of climate change, and thus refusal to take action on the problem, did not appear out of nowhere. It was “moved along by a campaign carefully crafted by fossil fuel industry players, most notably Charles D. and David H. Koch,” according to The New York Times. The Kochs have given at least $100 million to groups promoting climate denial since 1997, according to Greenpeace. Koch Industries is the twentieth-largest greenhouse gas polluter in the country, and thus stands to be hurt by climate change regulation.

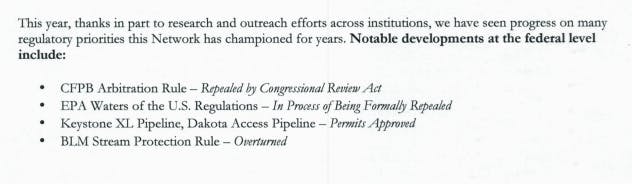

Koch Industries is also the fourteenth-largest air polluter and tenth-largest water polluter in America, according to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. That may explain the political network’s long quest to dismantle Environmental Protection Agency regulations. That effort has paid off under Trump, as the network noted in an internal memo obtained by The Intercept in February: The Koch network took credit for Trump’s approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, his withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, his dismantling of rules protecting streams from coal waste, and his allowance of fracking on public lands.

A partial screenshot of a Koch network document.The Intercept

A partial screenshot of a Koch network document.The InterceptAnother Koch value: the right to spend on politics in secrecy. As the Associated Press noted on Saturday, “there’s no way to verify how or where the [network’s] money is spent because most of its organizations are registered as nonprofit groups, which aren’t required to detail their donors like traditional political action committees.” The Kochs have been “reliable, stalwart opponents of regulation of money in politics,” the Center for Public Integrity reported last year, explaining how the Koch family underwrote and supported the legal landscape that permits dark money in politics today.

The network also accomplished numerous policy changes at the state level last year. Due to advocacy campaigns backed by Koch-affiliated groups, several states “have reduced union power, scaled back regulations, cut taxes, blocked Medicaid expansion, promoted alternatives to public education, loosened criminal sentencing laws and eased requirements to get occupational licenses,” according to The Washington Post.

The network has also launched a nationwide crusade against public transportation projects, and has built a data service called i360 to help “identify and rally voters” to support that cause, according to the Times. Like most of the Kochs’ political efforts, the anti-public transportation campaign “stems from their longstanding free-market, libertarian philosophy [but] also dovetails with their financial interests, which benefit from automobiles and highways,” the Times reported.

The Kochs’ values, in other words, are anathema to most Democrats. So who on the left would the Koch network be willing to support?

So far, there appears to be one: Senator Heidi Heitkamp, a moderate from North Dakota. Last month, Americans for Prosperity released an ad campaign thanking Heitkamp for supporting a bill to loosen financial protection regulations on small- and medium-size banks. The Koch network hasn’t pledged to financially support Heitkamp, who is facing a touch re-election bid in November; but they have said they don’t plan to support her Republican opponent, Kevin Cramer.

There is at least one area where Koch values and Democrats values might align. In a 2015 op-ed titled “the Overcriminalization of America,” Charles Koch and his business associate Mark Holden called for sweeping criminal justice reform marked by the end of mass incarceration, which the left has been demanding for years. But some anti-prison advocates worry the Koch’s push for reform is, at its core, about making money. As The Nation reported in March, “These critics fear that the libertarian reformers are more interested in replacing the carceral state with a privatized carceral industry than they are in coming up with humane alternatives to prison.”

Trump is right about this much: The Koch network doesn’t have much direct influence in the White House. As Axios noted last month, many Republicans believed the Kochs “had lost their influence during the rise of Trump.” But the network has shown that it can wield tremendous influence over congressional races. In his overtures to Democrats and censure of Republicans, Charles Koch may be attempting to remind the GOP of that power—and reassert it. But if indeed his network is losing political influence, and continues to do so, it’s hard to imagine Democrats’ lending a hand to help them regain it.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has already slayed some dragons. On foreign policy, however, the Democratic candidate for New York’s 14th congressional district is wielding a dull sword. On a recent episode of PBS’ Firing Line, Ocasio-Cortez failed to explain comments she’d previously made about the Israel-Palestine conflict. Asked what she meant by “the occupation of Palestine,” she dodged the question, saying: “I am not the expert on geopolitics on this issue.” As one of the most prominent self-identified democratic socialists in American politics, her stumble seems at odds with the political affiliation she’s publicly claimed. The website of the Democratic Socialists of America, of which she is a member, says it views “the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and its inhumane siege of Gaza as the major barrier” to peace in the region.

It’s reasonable to assume that Ocasio-Cortez would be able to defend this relatively common position. But it’s become common in recent years for left-wing politicians to either botch or dodge foreign policy issues. During 2016’s Democratic presidential primary, Senator Bernie Sanders initially failed to articulate much of a foreign policy platform—a strange oversight given that his opponent, Hillary Clinton, was a former secretary of state and a former senator who’d supported the invasion of Iraq. Sanders didn’t put forward a clearer foreign policy vision until 2017. “Foreign policy must take into account the outrageous income and wealth inequality that exists globally and in our own country,” he said during a 2017 speech at Westminster College.

Sanders may have helped spur 2018’s unusual slate of left-leaning congressional candidates. But his recent foreign policy commitments—reducing military spending, choosing diplomacy over military intervention—haven’t always filtered into the midterm races. This isn’t necessarily unusual for congressional races; candidates of all persuasions tend to campaign on issues of immediate importance to potential constituents. When left-wing candidates have looked beyond American borders, they have often done so on immigration and trade. Ayanna Pressley, who is challenging Democratic Representative Mike Capuano in Massachusetts’s 7th congressional district, offers an extraordinarily detailed immigration platform on her website that includes defunding Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Randy Bryce, the viral star of Wisconsin’s 1st Congressional District, similarly calls for abolishing ICE and the passage of a clean DREAM Act.

Midterm elections, when there are no national candidates on the ballot, may not be the best stage to premiere a cogent left-wing foreign policy doctrine. But midterms are also necessarily referendums on the White House, especially during a new presidency and especially in the Trump era. The president has: announced the U.S. will withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris climate accord; launched a trade war against China and imposed tariffs on allies like Canada and Mexico; restricted travel from several Muslim-majority countries; rolled back Obama’s Cuba opening; recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital; alternated between nuclear threats and diplomacy with North Korea; and consistently defended Russia. On Sunday, he threatened to shut down the government later this year if he doesn’t receive funding for his border wall.

Which is to say, foreign policy isn’t just an important issue ahead of the 2020 presidential election, but right now. Candidates like Ocasio-Cortez, if she wins the general election in her heavily Democratic district, may find themselves in control of the House of Representatives—in a position, in other words, to exert some influence over the president. That makes the left’s foreign policy vacuum all the more glaring.

The problem isn’t so much that left-wing candidates for Congress haven’t spelled out foreign policy positions on their websites—though that’s largely true—but that there’s little infrastructure to supply them with ideas once they take office. “There’s been an enormous failure by the progressive left, in terms of foreign policy-making think tanks. I mean, there’s just barely anything,” a senior Democratic congressional staffer told The New Republic. “The Democratic establishment—and I don’t want to just use that term because I think it’s broader than that—hasn’t been invested in foreign policy-making in the way that they should have.”

Washington has a bipartisan interventionist bent, to varying degrees. George W. Bush started two disastrous wars that still aren’t over. Barack Obama campaigned on ending the war in Iraq, and took steps to wind down the U.S. military’s involvement there, but vastly expanded Bush’s drone war, killing an estimated 324 civilians. Obama used airstrikes to overthrow Muammar Qaddafi in 2011; Libya is now a failed state, an outcome that likely influenced Obama’s decision not to intervene in Syria. And congressional Democrats have voted along with Republicans at pivotal moments. Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran spurred significant opposition from hawks in his own party, and during the Bush years, few Democrats opposed the invasions of either Afghanistan or Iraq. Representative Barbara Lee, now running to become the chair of the House Democratic Caucus, cast the lone vote against the Authorization of Military Force in 2001.

But it’s not always clear what a left-wing alternative to establishment policy would look like. In a 2014 piece for Dissent, Princeton academic Michael Walzer noted that there are many lefts, though some positions do seem consistent. Socialists, social democrats, and left-tilting populists tend to favor a domestic focus—to call for an expansion of the welfare state, for instance, rather than costly military adventures. “This is what I will call the default position of the left: the best foreign policy is a good domestic policy. How many times have we argued against foreign adventures and unnecessary wars by insisting that our fellow citizens would do better to focus energy and resources on injustice at home?” Walzer wrote.

There have been a few recent efforts to translate left ideas into concrete foreign policy positions. Our Revolution, an electoral group founded by veterans of the Bernie Sanders campaign, echoes Walzer’s thesis in its foreign policy platform. It urges officials to “move away from a policy of unilateral military action, and toward a policy of emphasizing diplomacy, and ensuring the decision to go to war is a last resort.” It also demands the closure of Guantanamo Bay and encourages fair trade and the provision of humanitarian assistance; its solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict is to ask Palestinians to recognize Israel’s right to exist and for Israel to end its blockade of Gaza and its settlement activity on Palestinian land.

Not all left-wing candidates this year are skimping on foreign policy. Kaniela Ing, a Native Hawaiian who is running to represent the state’s 1st congressional district as a democratic socialist, tweeted a video condemning interventionism. “We know that whether it’s a war on drugs or a war on terror, or whatever reason the White House makes up, it’s a war for profit and it’s a war causing indigenous people all over the world to suffer, just like we are in Hawaii,” he said. On Monday, he told me he sees a “transition” among progressives on the subject of interventionist wars. “Taking care of folks beyond our borders is part of caring for the most vulnerable,” he said, adding, “In terms of exactly what I’d vote on, it would be very very difficult for me support a war that doesn’t involve people on our shores attacking us.”

Rashida Tlaib, who is running to replace retired Representative John Conyers in Michigan’s 13th congressional district, expressed similar political commitments. “My approach to foreign policy will be guided by the same values that drive my approach to domestic policy: Empathy, understanding, and respect,” Tlaib said through a campaign spokesman. “I’m firmly anti-war, and I think that’s in large part influenced by my perspective as a Palestinian-American and having family and friends throughout the Middle East. I’ve seen firsthand how devastating military conflict is, and I think if more members of Congress actually knew the realities of war and regime change, they wouldn’t be so callous about dropping bombs in distant countries. We should be solving our problems with diplomacy, not by increasing our military spending budget.”

But even with these candidates, the message is rather one-note. There is more to foreign policy than war, and thus, there must be more to candidates’ foreign policy positions than anti-interventionism—to “end reckless wars,” as Ing’s website puts it, or to create a “peace economy,” as Ocasio-Cortez’s does. But expanding their platforms will require help, and it’s not clear to whom they can turn. Candidates to the left of the Democratic Party on foreign policy are likely also to the left of think tanks like the Center for American Progress, which backed Obama’s drone strikes and some airstrikes. There are no think tanks of analogous size and influence committed to crafting left-wing foreign policy.

“There is just no comparison between the left and right. I mean, I can think of at least five or six different right-wing think tanks that just do foreign policy, whereas there’s nothing like that for progressives,” the congressional staffer said. “That’s the huge problem.”

In Brett Kavanaugh’s long and distinguished career in law, one period stands out as especially important to him.

“People sometimes ask what prior legal experience has been most useful for me as a judge,” Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump’s nominee to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court, wrote in Marquette Law Magazine in 2016. “And I say, ‘I certainly draw on all of them,’ but I also say that my five-and-a-half years at the White House and especially my three years as staff secretary for President George W. Bush were the most interesting and informative for me.” Six years earlier, he made a nearly identical statement.

Given these remarks, it’s understandable that U.S. senators would be interested in his work and writings during his tenure in the Bush White House. After all, in the coming months they will be voting on whether to confirm Kavanaugh to a lifetime post on the Supreme Court. From there, he will spend the next three to four decades interpreting the Constitution and shaping the future of American law. Kennedy’s impact, as the court’s swing justice, on the nation’s lives and liberties underscores the gravity of this process and the need for maximal transparency.

Senate Republicans apparently disagree. Chuck Grassley, the Iowa senator who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a letter notifying Minority Leader Chuck Schumer last week that he was “not going to put American taxpayers on the hook” by seeking Kavanaugh’s records from his time as Bush’s staff secretary. (He will still request records from when Kavanaugh served in the White House counsel’s office.) It’s unlikely that those records, Grassley wrote, would provide “any meaningful insight” into how Kavanaugh would perform his judicial duties if confirmed to the Supreme Court.

Grassley is set to request from the executive branch more documents related to Kavanaugh than any preceding nominee. But that makes his refusal to request documents related to Kavanaugh’s tenure as staff secretary all the more bizarre. There doesn’t appear to be any reasonable justification to keep those documents out of the public eye before Kavanaugh’s confirmation vote, other than the concerns that you might find something that could prevent it.

Republican senators aren’t the only ones who have been critical of the Democrats’ request. National Review’s Ed Whelan, a prominent figure in the conservative legal movement, derided “Schumer’s delusory document demand,” arguing that Democrats should be satisfied with the records that the judiciary committee’s Republican chairman has already sought to obtain. “By any sensible measure, the document production—unprecedented in volume—that [Chuck] Grassley is arranging far exceeds what any senator could reasonably expect,” Whelan wrote.

The White House staff secretary oversees the flow of documents into and out of the Oval Office. Whelan quoted a colleague who described the position as a mere “traffic cop,” but that may be underselling it quite a bit. The staff secretary can provide notes, offer recommendations, prioritize certain issues above others, and exercise other subtle means of influence over the policymaking process. Rob Porter, who served in the role under Trump before resigning earlier this year amid allegations of domestic abuse, was described as an influential figure who provided “a competent, stabilizing presence in a dysfunctional, chaotic White House.”

As staff secretary from 2003 to 2006, Kavanaugh would have been well-placed to weigh in on some of the Bush administration’s most significant moments, including the Iraq War and its aftermath, the Abu Ghraib scandal and other torture-related policies, the reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act, the federal partial-birth abortion ban, and more. These issues aren’t unrelated to the judicial role he would perform on the high court, especially given that Kavanaugh has said how influential the staff secretary role was on his future performance on the bench.

The practical justifications for keeping these documents secret are unconvincing. Time is not an issue; there is no deadline on Kavanaugh’s nomination. Surely the Senate can wait a few weeks or months for the National Archives to complete the relevant process and for the senators’ staffs to review them accordingly. Republicans have been more than willing to let the court function with only eight justices in the recent past, when they torpedoed President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland, so any concerns about the Supreme Court’s ability to do its job when the justices reconvene in October are misplaced.

Grassley’s concerns about taxpayer funds are also unpersuasive. It’s hard to imagine a better use for tax dollars than properly vetting a potential Supreme Court justice. And if the nation’s coffers are truly so threadbare, perhaps the president would be willing to spare some of the $12 million he’s planning to spend on a self-indulgent military parade (or the $12 billion he’s spending to bail out farmers who theoretically will be hurt by his trade war). Trump could even use his personal wealth to hire some temporary National Archives personnel to accelerate the process as a gesture of good faith.

Grassley and Whelan also argued that seeking all of Kavanaugh’s White House records would break with precedent. They noted that back in 2010, while weighing Obama’s nomination of Elena Kagan to the court, Senate Republicans sought and received documents that covered her tenure in policy posts in the Clinton White House—but only because she hadn’t served as a judge before and therefore had no judicial record to scrutinize. The Republicans did not seek documents from her time in the Obama administration as solicitor general.

“Have in mind that there has never been a practice of insisting on all executive-branch records of a nominee,” Whelan wrote. “If any such practice existed, then the Obama administration would have been obligated to turn over all of Elena Kagan’s records during her year as the Obama administration’s solicitor general—information that would have been much more probative of her thinking on constitutional issues (and much more controversial) than her records from the Clinton White House.”

Fair point. But maybe Kagan and other Supreme Court nominees who work in the executive branch should turn over those documents to Congress as a general rule. In Kagan’s case, her solicitor general records likely would have held limited probative value. She was representing the Obama administration and the federal government as a whole in that position, not herself.

The Senate has good reason to be extra-cautious when it comes to judicial nominees who served in the executive branch, especially those who worked on legal policy matters for the Bush administration. In 2002, Bush nominated Jay Bybee to a lifetime position on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Senate approved his confirmation in 2003 by a 74-19 vote. The following year, it became public that during Bybee’s tenure as head of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, he had authored one of the post-9/11 torture memos that gave legal cover to U.S. officials who sought to perform it. At one point, he concluded that the federal law criminalizing torture would be unconstitutional “if it impermissibly encroached on the president’s constitutional power to conduct a military campaign.” Bybee’s successor later withdrew and repudiated the memos.

The revelations frustrated Democratic senators who had received vague answers from Bybee on the matter during his confirmation hearing. Senator Patrick Leahy, a former Democratic chair of the Judiciary Committee, said after the memo’s release in 2004, “If [Bybee’s] nomination were up today, knowing now what we weren’t permitted to know then, the Senate—this senator included—might not be so willing to give him the same benefit of the doubt for this lifetime appointment.” If Kavanaugh has any such skeleton in his closet, Senate Democrats want to see it before it’s too late.

No comments :

Post a Comment