It’s been an especially turbulent week for Donald Trump’s presidency, but consider this particular sequence of events:

First, a jury in Alexandria, Virginia, found Paul Manafort guilty Tuesday on eight felony counts related to tax evasion and other financial crimes. Manafort, who is 69 years old, now faces the possibility of spending a significant portion of his remaining life in federal prison. It’s possible, however, that the former Trump campaign chairman could reduce his prison sentence by cooperating with special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian electoral interference.

Second, on Wednesday, Trump expressed sympathy for Manafort and implicitly praised him for not cooperating with investigators. The Justice Department “took a 12 year old tax case, among other things, applied tremendous pressure on him and, unlike Michael Cohen, he refused to ‘break’ - make up stories in order to get a ‘deal,’” Trump tweeted, contrasting Manafort’s silence with his former lawyer’s admissions. “Such respect for a brave man!” That night, Fox News’ Ainsley Earhardt reported that Trump told her he was considering a pardon of Manafort.

Third, Rudy Giuliani, the president’s media-happy lawyer, told the Washington Post on Thursday that Trump asked his legal team in recent weeks whether he should pardon Manafort. Giuliani said that he and Trump’s other lawyers counseled against pardoning Manafort immediately. “We told him he should wait until all the investigations are over,” Giuliani told the Post. Mueller’s investigation, he added, “is a strange case. It won’t be decided by a jury. It will decided by the Justice Department and Congress and ultimately the American people. You have to be sensitive to public optics.”

Taken together, these events could suggest that if Manafort does not cooperate with the special counsel’s inquiry, he will receive a pardon at some point in the future. Since all of this has played out in national media outlets, it’s possible that Manafort himself and his legal team have already drawn a similar conclusion.

The president is already under investigation for obstruction of justice. But he may now be running afoul of other federal laws. In April, George Washington University law professor Randall Eliason wrote an interesting legal analysis about the presidency, the pardon power, and how they may intersect with federal bribery statutes. Eliason, who is a former federal prosecutor, emphasized that his analysis was academic in nature and that he was not accusing anyone of breaking the law. Nonetheless, his conclusions read even more salient today than they did five months ago.

Eliason pointed to two provisions in the federal bribery statute. The standard anti-bribery provision, he explained, “requires the government to prove that a public official agreed to be influenced in the performance of an official act in exchange for something of value.” Under this theory, the “official act”—that is, issuing a pardon—would be conducted in exchange for a thing of value, which is the witness’ silence. Eliason cited contemporaneous reports that John Dowd, a former Trump lawyer, floated the possibility of pardons to the lawyers representing Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn.

“If there was a conspiracy to solicit bribes, it doesn’t matter whether the solicitation was accepted,” he explained. “The crime would be the agreement between Dowd and the president to offer the pardons in exchange for silence, followed by some effort to try to carry out the agreement. In a conspiracy charge, success of the underlying scheme is not required.” Making all of those connections for a jury could be a tall order for any prosecutor, however.

Another provision in the statute deals specifically with bribery of a witness. In this formulation, the pardon becomes the thing of value that’s offered to someone, not the official act that’s undertaken to receive it. “Unlike theory A, this doesn’t require the government to prove that a public official was involved—anyone can bribe a witness,” Eliason wrote. “One potential benefit of this theory is that it could apply even if the president was not involved in the bribe.”

He then offered a hypothetical scenario that now feels awfully familiar. “For example, suppose Dowd or someone else close to the president told a witness, ‘Look, just don’t say anything in the grand jury, or lie about what happened, and I’ll get the president to grant you a pardon,’” Eliason wrote. “If I made such an offer it would not be credible and likely would not influence anyone to agree. But if the president’s personal lawyer or someone else actually in a position to persuade the president made such an offer, I think that promise could constitute a thing of value—even if the president was not aware of the offer.”

Trump and Giuliani haven’t explicitly said in public that Manafort will receive a pardon if he keeps his mouth shut. But a reasonable observer could conclude that such a pardon is on the table, and that cooperating with Mueller might make the president less inclined to grant it. That observer could also draw inferences from Trump’s behavior throughout the year. After all, the president has a habit of doling out pardons to people he considers to have been wronged by federal prosecutors, such as former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio and conservative provocateur Dinesh D’Souza. It’s certainly not unthinkable that Trump could offer Manafort a similar reprieve.

One could build on those conclusions with the president’s own words. In a Thursday morning interview on Fox and Friends, Trump also spoke out strongly against “flipping.” He was referring to the longstanding practice among federal prosecutors of getting lower-level defendants to testify against higher-level defendants in exchange for reduced sentences. It’s a ubiquitous tool for prosecutors across the country and an essential feature of any large-scale organized-crime case. In Trump’s eyes, however, the practice “almost ought to be illegal.”

“It’s not fair,” Trump complained in reference to Cohen, who implicated the president in campaign-finance violations when he pleaded guilty earlier this week. “If you can say something bad about Donald Trump and you will go down to two years or three years, which is the deal he made, in all fairness to him, most people are going to do that.” What the president said is likely true—unless, of course, Trump or one of his associates gives the defendant a good reason not to do so.

Medicare for All is no longer just a left-wing pipe dream. With polling increasingly in its favor and a record number of Democratic senators and representatives onboard, the idea of expanding Medicare—a government health insurance program for people 65 and older—to all Americans seems like a viable proposal. The case for it was bolstered recently, albeit inadvertently, by a working paper last month from the libertarian, Koch-funded Mercatus Center, which concluded that Senator Bernie Sanders’s plan would save the American public more than $2 trillion over a ten year period.

The paper’s author, senior researcher Charles Blahous, hadn’t meant for that to be the takeaway from the paper, and has repeatedly disputed the $2 trillion figure. Thus began a debate, which is still raging, among partisans and journalists about how to accurately characterize the study. The details and scale of this debate may presage the obstacles Medicare for All will face as its backers seek to make it law.

In a summary of his conclusions, Blahous wrote that Medicare for All would cost the government around $32.6 trillion over its first decade—or $3.26 trillion per year, which is almost exactly how much the government expects to raise in revenue this fiscal year. “Doubling all currently projected federal individual and corporate income tax collections would be insufficient to finance the added federal costs of the plan,” he wrote, adding that it’s “likely that the actual cost of M4A would be substantially greater than these estimates.”

But as Matt Bruenig of People’s Policy Project noticed, a table in the paper shows that while federal spending on health care would increase significantly under Medicare for All, overall health spending—from the federal government, state governments, and private employers combined—would fall by $2 trillion. This is because “the new costs it creates would be more than offset by the new savings it generates through administrative efficiencies and reductions in unit prices.” The headlines in left-of-center media outlets wrote themselves, and Sanders, in a video published on social media, sardonically thanked “the Koch Brothers of all people” for sponsoring the study.

Thank you, Koch brothers, for accidentally making the case for Medicare for All! pic.twitter.com/speuEL6ETC

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) July 30, 2018Enter the fact-checkers: The Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler awarded Sanders three out of four “Pinocchios” for saying that the study “shows that Medicare for All would save the American people $2 trillion over a 10-year period.” To arrive at his claim, Kessler largely accepted Blahous’s characterization of Sanders’s plan, which estimated that the senator’s version of Medicare for All would cut provider payments by about 40 percent. “That in theory would reduce the country’s overall level of health expenditures by $2 trillion from 2022 to 2031,” Kessler wrote. “But [Blahous] makes clear that it’s a pretty unrealistic assumption.” Kessler thus said Sanders had “cherry-picked” the $2 trillion figure from the paper. Politifact likewise concluded that Sanders “cherry-picked the more flattering of two estimates,” and rated Sanders’s statement “half true.”

Ryan Cooper of The Week took stock of these and other criticisms of the $2 trillion figure, writing on Tuesday, “The fact checker brigade is saying that provider payments will be hard to cut, and therefore Sanders might end up passing something different than his Medicare bill. Therefore he is a liar. But Blahous’s study absolutely, positively does say that the Sanders plan as written will save the American people $2 trillion…. Vague speculation about future political negotiations has nothing whatsoever to do with the facts of the Sanders proposal, nor the empirical contents of the Mercatus study.” Blahous’s 40 percent estimate, which Kessler and Politifact repeated, also might not withstand mathematical scrutiny: Bruenig reverse-engineered Blahous’s own tables and figured the actual cut would be somewhere around 10.6 percent.

Kessler updated his article—he had originally, erroneously included drug companies in a list of providers to face cuts—but not his rating of Sanders’s statement. Meanwhile, in a fact-check video, CNN’s Jake Tapper also accused Sanders of misrepresenting the Mercatus study. “The study’s author says that that $2 trillion drop is not actually his conclusion. He says that’s based on assumptions by Senator Sanders,” Tapper said, echoing Kessler. But as Sanders noted in response, the Medicare for All bill didn’t actually base its calculations on assumptions. Tapper also mischaracterized the senator’s remarks, claiming Sanders said the government would save $2 trillion. In truth, Sanders said “the American people” would save $2 trillion. Tapper rescinded that claim, and CNN has edited the error out of the video.

@BenSpielberg @ryangrim Yes, the point made about the “American people” versus “the government” is on point and totally valid so we’re going to redo that part of the video.

— Jake Tapper (@jaketapper) August 19, 2018But Medicare for All’s critics don’t just worry about the proposal’s cost. An August 21 story by Politico said single-payer healthcare has “proved a tough sell” for Democrats in swing districts. “The problem is Medicare for all just isn’t one of those litmus tests for Democratic primary voters,” Democratic strategist John Anzalone told the outlet. (The story goes on to report that Anzalone’s firm campaigned successfully against a single-payer advocate in Iowa.) It is certainly true that a number of single-payer advocates have lost primary and general elections this year—though the same can be said of Democrats who didn’t back Medicare for All or a similar policy. It might also be true that most voters don’t enter the polling booths with Medicare for All in mind. It doesn’t necessarily follow, however, that voters are turned off by Medicare for All, to the degree that support for the policy will cost candidates their general elections. As the Politico piece itself notes, candidates lose races for all kinds of reasons. The uneven showing by Medicare for All supporters does show that the policy isn’t a magic key to winning votes, but most policies can’t lay claim to that sort of power anyway.

Nobody really denies that Medicare for All will be expensive. There’s not even consensus on what Sanders’s plan would actually cost the federal government. As Politifact reported in July 2017, “Kenneth Thorpe, a professor of health policy and management at Emory University, put the cost at $2.4 trillion a year. A team from the Urban Institute put the number at $2.5 trillion a year. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projected $2.8 trillion a year.” An American transition to a single-payer system would almost certainly increase taxes for some Americans—the wealthiest households—and repeal some tax breaks for corporations and homeowners. For these reasons, single-payer will remain a tough sell to wealthy conservatives like the Koch brothers.

It’s less clear that Medicare for All is a non-starter with voters. A poll published Thursday by Reuters found that 85 percent of Democrats support Medicare for All, and that even 52 percent of Republicans do, too. That’s a sharp increase from a Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation poll in April that found that just over half of all Americans support a single-payer system; Medicare’s name recognition and popularity perhaps accounts for the difference between these polls. Support also appears to be somewhat conditional on how pollsters describe the policy to voters. “Opposition grew to 61 percent when supporters were told it would ‘give government too much control over health care,’” The Washington Post reported, citing a different Kaiser Family Foundation poll. That’s a bit at odds with a 2017 Associated Press/NORC poll, which found that 60 percent of respondents believe it’s the government’s responsibility to provide healthcare.

But there’s more to politics than polls. Medicare for All would hardly be the first expansion of the welfare state to be deemed a threat to liberty or too costly. “Many of the New Dealers have no concern whatever for individual freedom,” Senator Robert Taft declared in 1939. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was, he added, “absolutely contrary to the whole American theory on which the country was founded and which has actually made it the most prosperous country in the whole world.” Politifact might have rated Taft’s statement half-true. The New Deal indeed represented a departure from the order the Founders thought they had established—an order that granted citizenship only to white male landowners, and preserved the institution of slavery. The American theory evolves, but these evolutions are never inevitable. They are forced, the product of public demands and popular struggle.

The New Deal, as well as Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs, were sold in moral terms—a lesson for Democrats as they push Medicare for All. While they do have to account for the policy’s costs, and for the difficulty of transitioning the nation’s healthcare system to a single-payer model, debates over funding and electoral viability miss the real point. The question isn’t whether the transition will be easy; it won’t be. The question is whether or not Democrats believe healthcare is a human right.

America doesn’t regard it as such, and it shows. The U.S. is the deadliest developed nation for expectant mothers, a fact researchers attribute in part to a lack of access to preventable health care. Children sell lemonade to pay for family member’s medical procedures. GoFundMe is a graveyard of failed crowdfunding campaigns. Even when Americans have private health insurance, they can face egregiously large, unexpected bills for emergency care—even at in-network hospitals. In May, Vox reported that it had collected 1300 emergency room bills from patients that demonstrate the scale of the problem, which stems from a systemic flaw in our privatized system: A hospital might be in-network, but an emergency room physician might not be. Americans can do everything right—get jobs that provide benefits, pay their premiums, check to see if facilities are in network—and still face insurmountable financial obstacles to care. The research is clear about the consequences. People get sick, and people die, when they don’t get health care.

That’s why Sanders seized on that $2 trillion figure. If even the Mercatus Center concedes that Sanders’s bill, as written, would lower individual health costs for Americans while expanding access to affordable care, then what do Medicare for All’s critics really object to? The idea that all Americans deserve to have health care, and that it should never bankrupt them? It’s not Sanders and other single-payer advocates who have the most explaining to do. It’s those who insist that Medicare for All will be worse than the realities the American people endure today.

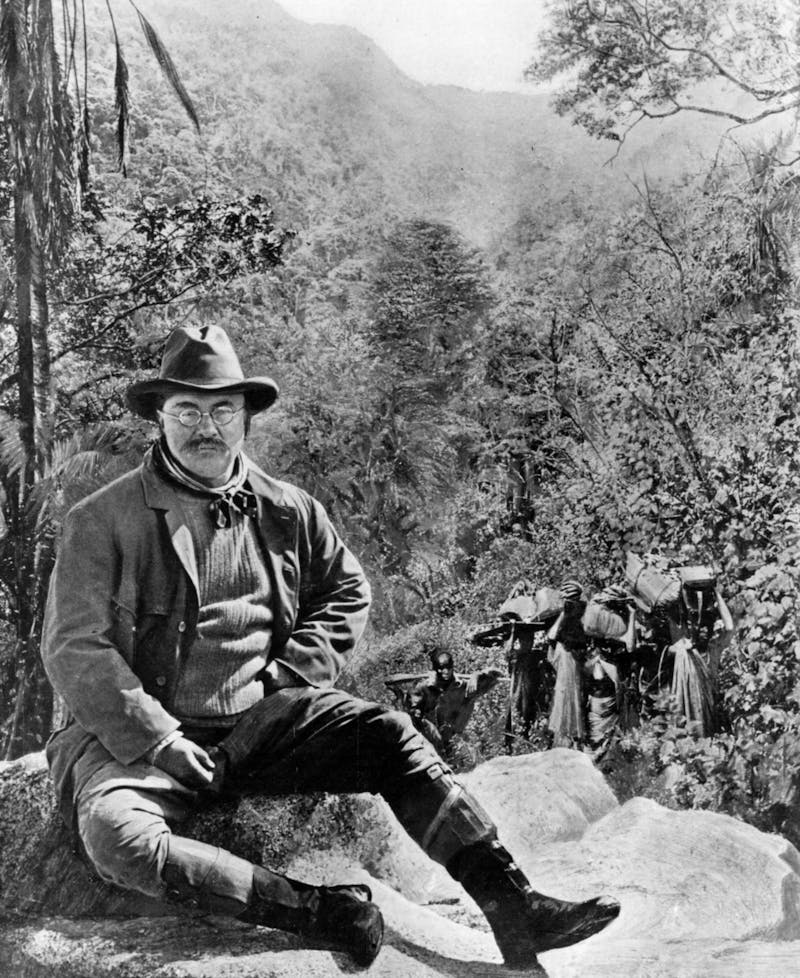

In 1909, after the end of his second term as president, Theodore Roosevelt went on safari in Africa with his son Kermit. Financed by Andrew Carnegie and a $50,000 advance from Scribner’s Magazine, the Roosevelts travelled from Kenya to the Sudan, sending back samples to the Smithsonian as they went. The African porters gave the paunchy ex-President a mocking nickname, Bwana Tumbo (“Mister Stomach”) in Swahili. When he overheard and asked what it meant, they told him it was “the man with the unerring aim.” Perhaps the joke was also metaphorical, since Roosevelt did have quite the appetite—and stomach—for shooting things. By the end of the trip, he and Kermit had personally bagged 11 elephants, 17 lions, and 20 rhinos.

THE FAIR CHASE: THE EPIC STORY OF HUNTING IN AMERICA by Philip DrayBasic Books, 416 pp., $32.00

THE FAIR CHASE: THE EPIC STORY OF HUNTING IN AMERICA by Philip DrayBasic Books, 416 pp., $32.00A century ago, these hunting exploits made Roosevelt the toast of the American press—a reaction that is hard to understand today, when social attitudes toward trophy hunting have sharply reversed. As for attitudes toward hunting more generally, the picture is complicated: Some 70 percent of Americans say they approve of it, but only a small proportion now regularly do it themselves—around 12.5 million a year. Meanwhile, the cultural politics of hunting have become thornily intertwined with debates over guns and gun control. Liberals frequently concede a right to bear arms for hunting (although the Constitution specifies no such thing) and conservatives often present gun ownership for hunting and self-defense as politically indistinguishable (even though many hunters support various gun control measures, and self-defense, not hunting, is now the primary stated reason for gun ownership in America).

In his lively and compelling book The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America, Philip Dray acknowledges these tensions, deepening and complicating them by putting them in historical context. His book offers a capacious and erudite history of the practice and meanings of hunting in American life, from settlers trapping beaver on the Colonial frontier to twenty-first century fights over land use and endangered species. If any book might possibly foster “dialogue between nonhunting lovers of nature and adherents of the chase,” The Fair Chase is it. Written with sensitivity and bracketed judgment, it describes a culture and asks questions, telling a story full of paradoxes and nuance.

Hunting in America has always been criss-crossed by social and political faultlines. Like many popular and longstanding American phenomena—from football to racing cars—hunting and its roots are simultaneously aristocratic yet plebian, aspirational and visceral all at once. On the one hand, from the start, American settlers hunted as a matter of day-to-day survival, and appropriated the techniques of Native Americans to that end. But Americans were also drawn to the glamour and cachet of aristocratic British hunting culture. This combination produced a uniquely American hunting culture that was at once cosmopolitan yet local, patrician yet democratic. And what became a core part of the American identity for some, others have strongly rejected.

In England, hunting had long been a pursuit of royal courts and wealthy nobles. Like her father, Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth adored hunting, and did it in on horseback well into her late seventies. With a keen eye for colorful detail, Dray narrates the elaborate rituals of the English hunting tradition, and samples its rich vocabulary, from “nouns of assembly” (“a sloth of bears” or “a business of ferrets”) to nomenclature (a six-year-old stag that evades a king or queen is dubbed “a hart royal proclaimed”) to flowery euphemisms for different kinds of scat. (Bears, it turns out, do not shit in the woods: They leave “lesses”).

American elites carried on the enthusiasm for hunting of their British counterparts. Whenever he could, George Washington hunted foxes in the British manner, on horseback and with hounds. But colonial and Revolutionary America also had a different kind of hunting elite: backwoodsmen who were deadshot marksmen and who, using techniques often learned from Native Americans, became experts at hunting North American game. Through their service in the Seven Years and Revolutionary Wars, such hunters went from shaggy disreputability to celebrated icons of American self-reliance, patriotism, and mastery over nature.

Roosevelt on a hunting tour in Central Africa in 1909Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Roosevelt on a hunting tour in Central Africa in 1909Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesDray focuses particularly on the story of Daniel Boone, whose cultural impact he places on the same level as the Founding Fathers. Born in Pennsylvania in 1734, Boone was one of the first whites to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains, and was already a noted Native American fighter and hunter when his story first appeared in 1784. Presented as an adventurous, hardy, and straight-shooting (in all senses) frontiersman, Boone became a living folk hero, and set a template for a certain American character, one for whom hunting was a defining pursuit. (His story was in fact written by a land speculator who hoped that Boone’s example would encourage people to move to Kentucky, and boost returns on his own investment.) Subsequent larger-than-life figures, from Davy Crockett to Buffalo Bill to Theodore Roosevelt would all draw, in different ways, on this archetype.

Whether in cheap broadsheets or erudite philosophical meditations, American writers were instrumental in building up the legendary status of many more figures like Boone. For literate audiences, such stories reinforced a sense of national confidence, and connected urban dwellers with the frontier as America expanded. They also presented hunting as an activity that mixed the “earthy charms” of rustic life with the “manly bonhomie” of aristocratic recreation. A generation before Mark Twain, early nineteenth-century newspaper writers regaled their readers with frontier tall-tales like “Chunky’s Fight With the Panthers” and “How Sally Hooter Got Snakebit.” In this same period, Henry William Herbert, a prodigal son of the British aristocracy turned New York sports writer, adopted the pen name “Frank Forester” and produced an immensely popular series of lightly fictionalized stories about expatriate British gentry hunting in the forests of Warwick, New York.

As America industrialized and middle-class workers spent ever more time in stores and offices, hunting was increasingly presented as an opportunity for healthy, character-building return to nature. “Out upon these scholars!,” proclaimed Ralph Waldo Emerson, “with their pale, sickly etiolated indoor thoughts! Give me the out-of-door thoughts of sound men, thoughts all fresh and blooming.” Emerson himself was a hunter, going in the 1850s on regular excursions to the Adirondacks organized by landscape painter William Stillman, in which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and naturalist Louis Agassiz also joined.

The fundamental appeal of hunting stories, Dray observes, is the core “unique narrative power” of the hunting story as a genre itself. A quarry is pursued, and challenges are met. It is hard to imagine a more basic (or concisely compelling) formula. Yet the appeal of such stories was far from universal: Some Americans have long had moral scruples about killing animals for sport—and for many Native Americans, wanton hunting by whites was quite literally an existential threat.

As the nineteenth century proceeds, and America’s frontier expands, Dray’s cast of characters multiplies. Big-game-crazed European nobility undertake lavish expeditions in the American West, hunting not just exotic animals but occasionally more idiosyncratic (emotional and sexual) goals as well. Pioneers, hunters, and cowboys make their names—Texas Jack, Calamity Jane, and Bill Hickock, among others—and become dime-novel celebrities. Some scenes are surreal, as when the Romanov Grand Duke Alexis, son of Czar Alexander II, hunts on the Great Plains alongside Buffalo Bill and Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Others are devastating: Dray tells of a German immigrant hunter, Frederick Gerstaecker, who is puzzled by finding so many Native American remains in a Southern forest, until he realizes he is on the path the Trail of Tears:

Many a warrior and squaw died on the road from exhaustion… and their relations and friends could do no more for them than fold them in their blankets, and cover them with boughs and bushes, to keep off the vultures, which followed their route by thousands, and soared over their heads; for their drivers would not give them time to dig a grave and bury their dead.

This last episode suggests something crucial: Any story of whites hunting in America, whatever their class or ethnicity, is also story of native communities being ethnically cleansed from that same territory. Dray does not hesitate to remind the reader of this fact repeatedly.

American hunters would down entire flocks of birds, selling them by the penny for pies; tourists sniped buffalo for the thrill of it from stopped trains.Nor does he shy away from the frequently queasy aspects of the history he unpacks. For all its grandeur, America’s romance with hunting also reveals unpleasant truths about the country’s capacity for limitless consumption, environmental recklessness, and indifference to both human and animal suffering. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the American appetite for game meat and animal products grew almost incomprehensibly ravenous. Using massive “punt-guns” (basically cannon-sized shotguns), American hunters would down entire flocks of birds, selling them by the penny for pies (a dozen birds in each) or harvesting feathers for a lucrative trade in plumed ladies’ hats. Entire species were driven to the edge of extinction, and some, like the passenger pigeon, over it. “Market hunters” armed with high-power rifles flooded the prairies, killing buffalo at rates as fast as a hundred buffalo per man per hour; tourists sniped buffalo for the thrill of it from stopped trains and then left the carcasses to rot. William T. Hornaday, the first director of the Bronx Zoo and a founding father of American wildlife conservation, documented a loss of fifteen million buffalo from 1867 to 1887.

The loss of these species sparked movements for conservation and against animal mistreatment, from the Audubon Society to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Sports hunters themselves led much of this groundswell of activism, since they had not only witnessed the ravages of extinction firsthand, but also had a sincere interest in maintaining wild spaces and animal populations for their own use. Indeed, it was largely the efforts of organizations like the Boone and Crockett Club (founded in 1887 by Theodore Roosevelt) that built the political momentum to create the National Park System and enact legislation creating hunting seasons and protecting migrating birds. Hunters and hunting activists formally put forward the idea of a “Fair Chase,” a set of rules stipulating supposed sportmans-like conduct towards game. And the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937, known as the Pittman-Robertson Act, established an 11 percent excise tax on ammunition and hunting gear.

All this may be surprising for some readers, particularly for those who view hunting and hunting culture with distaste. Environmentally-conscious liberals are indeed often repulsed by the idea of forming political coalitions with people who, they may argue, are interested in animals only because they want to kill them. “If a person believes it is immoral to shoot and kill an innocent wild animal,” Dray observes, “no counterargument about hunting as a means of maintaining wildlife population levels or people getting back in touch with nature is likely to resonate.” But, as Dray also pointedly notes, the anti-hunting public has often proved unwilling to pick up the conservation slack: Attempts to extend Pittman-Robertson-style taxes to other outdoors gear, like hiking supplies, have all failed.

Meanwhile, many people who oppose hunting are fairly indifferent to the fate of billions of animals kept in abominable conditions for food in factory farms, or to the wild animals inevitably killed in the production of even vegan or organic produce. “If humankind’s presence alone causes animals to die,” Dray observes, “it might lend credence to the hunter’s claim that as man is already deeply involved in animal destruction, hunting is simply its most honest manifestation.”

Today, left-leaning environmentalists must navigate a political landscape in which they may find themselves bedfellows with gun rights activists.As The Fair Chase amply demonstrates, the cultural politics of conservation, like the cultural politics of hunting, have always been tangled. William Hornaday, the zoologist who lamented the fate of the buffalo and helped inaugurate the modern conservation movement, was also a scientific racist who put a Congolese pygmy on display in a primate exhibit, and who thought immigrants from Southern Europe were “bird-killing” vermin. And today, left-leaning environmentalists eager to oppose oil pipelines or the de-listing of National Forests must navigate a political landscape in which they may find themselves bedfellows with gun rights activists and firearm industry lobbyists.

As Dray so powerfully demonstrates, debates over conservation, like debates over hunting, have always illuminated certain core contradictions in American culture: tensions between the urban and rural, between the natural world and capitalist extraction, between elites and the general populace. The path forward, if there is to be one, seems to lie in both perceiving these tensions while working with them, one way or another. As an unrivaled history, and an admirably crafted bid to deepen dialogue between groups of Americans who might otherwise view one another as alien or out of touch, Dray’s Fair Chase is a vital intervention.

The United States may not quite be in a constitutional crisis, but it certainly feels like one. With Michael Cohen’s guilty plea this week, and his admission in court that he paid illegal hush money to two women at then-candidate Donald Trump’s behest, the president is effectively an unindicted co-conspirator in a plot to break campaign-finance laws to influence his own election. What’s more, it’s not even the plot he’s denied taking part in for more than a year.

The guilty plea by Trump’s former personal lawyer sends this presidency, and the nation, even further into uncharted waters. There’s now a deep unease across the American political spectrum, a sensation akin to the swelling hum of instruments as an orchestra warms up for its performance. Politico reported that Tuesday’s legal maelstrom “left an unavoidable impression that the walls are closing in on a president facing serious accusations of wrongdoing” among White House staffers. Elsewhere in Washington, Trump’s opponents appear to sense the advantage turning in their favor.

“Enough is enough,” New York Representative Jerrold Nadler said in a statement on Wednesday. “The President of the United States is now directly implicated in a criminal conspiracy, numerous members of both his campaign and administration have been convicted, pleaded guilty to felonies, or are ensnared in corruption investigations, and the Judiciary Committee has real work to do.” If Democrats retake the House this fall, Nadler would preside over impeachment hearings as chairman of that committee.

There is no clear path to how all of this ends. Trump’s political wounds are so grievous, and his unpopularity so thoroughly baked in for the American public broadly (just as, conversely, his popularity with Republicans is), that it’s hard to imagine how he could ever have anything resembling a normal presidency. At the same time, it’s unclear if his opponents could successfully oust him through impeachment. Many of these questions depend on the fate of the 2018 midterms, and perhaps all depend on whatever legal twists and turns come next.

Trump’s chief advantage at the moment is that he is the president. Without that office, he would be as susceptible to an indictment for criminal wrongdoing as any other American. There’s a robust debate among legal scholars on whether a president can be indicted while in office, but the question is effectively moot since it would violate current Justice Department guidelines. It’s a grim paradox that the man commanded by the Constitution to “faithfully execute” the laws of the United States is also the person who is least beholden to them.

This problem is not completely new, of course. Two presidents have been formally implicated in criminal behavior in Trump’s lifetime. The archetypal case is the Watergate crisis, when Richard Nixon tried to cover up a break-in of Democratic headquarters by his associates. More recently, the House of Representatives impeached Bill Clinton for lying to a federal grand jury about his relationship with a White House intern. (He was subsequently acquitted by the Senate.)

At some point, Trump will no longer be the president. Should he be indicted then? No president has ever faced criminal prosecution after leaving office, though it has been contemplated. Nixon’s resignation immediately raised the question of whether he would face criminal charges. Leon Jaworski, the Watergate special prosecutor, did not reach a definitive conclusion on whether to proceed because he was waiting for the trial of John Mitchell, Nixon’s former attorney general, to wrap up first.

“A decision on whether or not to indict was not a pressing matter at the moment because, had the decision been to indict, action would not have been taken until after the jury had been selected and sequestered in the Mitchell, et al. cover-up case, then set for the last day of September, because otherwise any indictment of Nixon would have meant an indefinite delay in that trial,” he later recalled in a Fordham University lecture. While the matter was being studied, President Ford moved to pardon former President Nixon.”

Ken Starr, the independent counsel who investigated Clinton for most of the 1990s, left that position in September 1998. His successor, Robert Ray, opted against prosecuting Clinton after the president’s acquittal by the Senate. Instead, he struck a plea bargain of sorts with the outgoing president on his last day in office. Clinton agreed to a five-year suspension of his law license and admitted to “testifying falsely” about his sexual relationship with Monica Lewinsky. In his final report on the matter in 2002, Ray said he believed he could have successfully prosecuted the ex-president for lying to the federal grand jury four years earlier.

That leaves impeachment as the likeliest check on Trump’s power. Congress is supposed to keep the president accountable under the tripartite system of American government, at least in theory. But it has largely abandoned that duty under Republican rule. A substantial clique of House Republicans have spent the last year using their oversight powers to actively undermine the Justice Department’s investigations of Trump. House Speaker Paul Ryan has allowed California Representative Devin Nunes and the clique’s other leaders to keep their committee chairmanships despite the damage they are doing to Congress’s institutional credibility.

If Democrats retake the House in November, impeachment proceedings are far more likely than they are now. But the party doesn’t appear to be convinced that it’s a politically winning issue so far. Democratic leaders in Congress studiously avoid discussing it, as do most (but not all) of the rank-and-file members. Tom Steyer, a billionaire Democratic donor who’s spent millions of dollars promoting impeachment since Trump took office, has reportedly expressed anger toward the party’s leaders for downplaying the issue.

Unforeseen events could change the Democrats’ calculus. If Mueller finds and reveals evidence of serious wrongdoing on the president’s part, it could push Democrats and even some Republicans towards removing him from office. Firing Mueller or shutting down his investigation would likely prompt a similar level of blowback in Congress. But events could also shift in Trump’s favor. Democrats are likely to but not guaranteed to retake the House in this November’s midterm elections; they are much less likely to win the other chamber of Congress, which holds the power to convict or exonerate an impeached president. If Republicans manage to hold on to the House and expand their majority in the Senate, even proof of outright collusion might not be enough to oust him.

After Cohen’s guilty plea, the risk of an explosive counterattack from the president is also even higher. “When Trump is cornered, he is at his most dangerous, as several people close to him have said,” New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman wrote on Twitter on Wednesday. She noted that Trump behaved as though he “had nothing to lose” when the Access Hollywood tape came out during the 2016 election. “This is a different order of magnitude, touching on his business and potentially family,” Haberman wrote.

Trump has already shown a willingness to take extraordinary steps as president in his own self-interest. After his failed attempt to secure FBI Director James Comey’s personal loyalty failed last spring, the president unceremoniously ousted him midway through his ten-year term and then publicly threatened him to keep quiet. Trump also reportedly tried to fire special counsel Robert Mueller last December, only to back down when White House Counsel Don McGahn refused to carry out the order. In recent months, he has increasingly used his Twitter presence to hound and denigrate FBI employees who could be potential witnesses against him.

If tweets aren’t enough, Trump could resort to even more aggressive measures. Jack Goldsmith, who ran the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel under George W. Bush, warned of three possible steps that Trump could take to curtail the Russia investigation after Cohen’s plea deal. First, he could pardon key participants like newly convicted felon Paul Manafort, freeing them from pressure to cooperate with Mueller’s inquiry. Second, he could trigger another Saturday Night Massacre by ordering Justice Department officials to fire Mueller, which many of them would likely refuse to do. Finally, he could weaponize his control over the security-clearance process and yank them from Mueller’s team, as he already did to former CIA Director John Brennan earlier this month.

Any of those moves would likely push many Democrats, who are already planning for such scenarios, and even some Republicans toward removing the president from office. But nothing is guaranteed, and all of the structural advantages are in Trump’s favor. It would take extraordinary acts or revelations for Trump to become the first president to be indicted or impeached. But these also happen to be extraordinary times.

No comments :

Post a Comment