Lukas Schulze/Getty Images

Lukas Schulze/Getty ImagesThe National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Monday released yet another dismal monthly report on the state of the global climate, concluding that last month was the fourth-hottest July ever recorded globally and that 2018 is shaping up to be the fourth-hottest year on record. The federal agency also found that sea ice levels in the Arctic and Antarctic were well below average. Nowhere in the world saw a single record cold temperature.

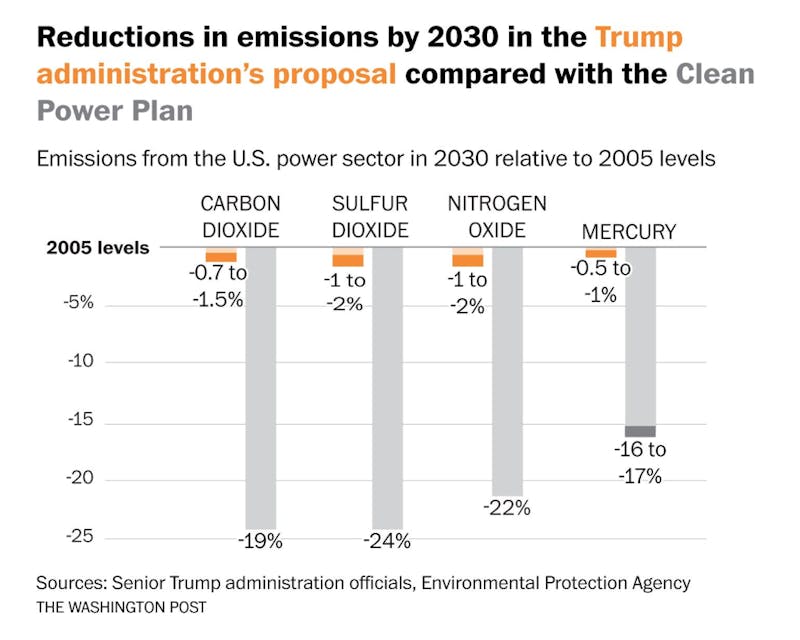

President Donald Trump is expected to unveil a plan that, if implemented, would warm the planet even further. Trump reportedly will travel to West Virginia on Tuesday to announce new greenhouse gas regulations for coal-fired power plants—effectively a proposed replacement of the Clean Power Plan, President Barack Obama’s signature policy to fight global warming. Trump’s plan “would allow individual states to decide how, or even whether, to curb carbon dioxide emissions from coal plants,” The New York Times reported. “The plan would also relax pollution rules for power plants that need upgrades. That, combined with allowing states to set their own rules, creates a serious risk that emissions, which had been falling, could start to rise again, according to environmentalists.

Compared to the Clean Power Plan, Trump’s plan effectively would add 300 million tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere—the equivalent of more than 64 million cars driven for a year. Or, as The Washington Post put it, Trump’s plan would “release at least 12 times the amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere compared with the Obama rule over the next decade.”

“These numbers tell the story, that they really remain committed not to do anything to address greenhouse gas emissions,” Joseph Goffman, an environmental law professor at Harvard, told the Post. In truth, these numbers tell only part of the story, as the Clean Power Plan is just one out of several climate change regulations Trump plans to undo. The cumulative impact of those repeals, if successful, would be far greater than adding 64 million cars to the road. It could be more like 340 million.

Obama implemented a regulation to limit leaks of methane—a powerful greenhouse gas—from oil and gas operations. Finalized in 2016, the rule was intended to prevent the equivalent of 11 million metric tons of carbon dioxide escaping into the air by the year 2025. The Trump administration has moved to repeal that rule without a weaker replacement. The courts will ultimately decide whether he succeeds, but if he does, it could result in two million cars’ worth of emissions added to the atmosphere.

But that’s nothing compared to the projected impact of Trump’s recently announced plan to repeal and replace Obama’s fuel efficiency rules for vehicles. From The New York Times (emphasis mine):

Assuming the plan is finalized and survives legal challenges, America’s cars and trucks would emit an extra 321 million to 931 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere between now and 2035 as a result of the weaker rules, according to an analysis by the research firm Rhodium Group. A separate estimate by the think tank Energy Innovation pegged the number even higher, at 1.25 billion metric tons.

In other words, Trump’s new fuel efficiency rule would have the same climate effect as putting 68 to 267 million cars on the road for a year. Add his Clean Power Plan replacement and methane rule repeal, and the effect would be an additional 140 to 339 million cars. That’s the same as adding 164 to 397 coal-fired power plants to the grid for a year.

Those emissions would only hasten the slow-motion catastrophe of climate change. National Geographic reported on Monday that some Arctic permafrost—which is supposed to be permanently frozen—is no longer freezing even in winter. Permafrost contains greenhouse gases, which get released into the atmosphere when it thaws. Those gases then cause more warming, which causes more permafrost thaw. “This is a significant milestone in a disturbing trend,” permafrost expert Ted Schuur told the magazine. It’s one of many disturbing climate trends that seem certain to continue under Trump.

Before the 2016 election, a woman showed up at Hillary Clinton’s headquarters in Flint, Michigan, asking for a lawn sign and offering to canvass. She was told those efforts were not “scientifically” significant ways to get votes and was turned away. After Clinton lost Michigan and, of course, the election, the story, reported in Politico months later, became emblematic of a suicidal campaign locked into algorithms and metrics while ignoring messaging. But it also illustrates a larger conundrum for Democrats, one that dates to the late 1960s. It was then that the Democrats, in a shift that ultimately crippled their ability to win elections, began to rely on narrow policy arguments, each tailored toward a different constituency, over grand, national narratives capable of uniting their base.

In 1964, a political scientist named Philip E. Converse published a chapter in a book called Ideology and Its Discontents, in which he argued that voters selected leaders they thought would benefit their “group,” rather than basing their decisions on broader political ideologies. His observations launched 50 years of research into voter behavior, from push polling to the effect of weather on electoral outcomes. This changed both parties, but Democrats most of all. Republicans adopted data and metrics, too, but they also crafted a powerful story—of the little guy crushed under the heel of a huge government bureaucracy that props up lazy ingrates—that would dominate American politics for the next 40 years. It is only recently that the Democrats finally seem to be developing a clear political message of their own.

Since the end of the Progressive Era in the early twentieth century, there have been two great narratives in American politics. In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal united urban Democrats and racist Southern Democrats, African Americans who could still vote, Republican businessmen, and Western Progressive Republicans—the “sons of the wild jackass”—by offering a vision of American society in which the federal government protected its citizens from the disastrous effects of runaway crony capitalism. For decades, Democrats would build their policies, including Johnson’s Great Society, on this idea.

In the 1950s, another powerful political narrative emerged, this time from the other side of the political spectrum. It was a mythological tale of the little guy against the giant; David against Goliath; “individual freedom” against the “ant heap of totalitarianism,” as Ronald Reagan put it in a 1964 speech supporting Barry Goldwater. No longer a protector, the federal government was transformed into an oppressor, an institution commandeered by liberals who took from hard-working Americans and gave to the undeserving. Developed at William F. Buckley Jr.’s National Review in the late 1950s and ’60s, it was embraced by Barry Goldwater, developed by Richard Nixon, honed by Reagan a decade later, and used by Newt Gingrich in 1994 to purge the Republican Party of traditionalists.

By then, Democrats had largely ceased to articulate FDR’s ideas. But they didn’t really try to craft a new story about America either. Bill Clinton and his successors in Democratic politics bought in to the basic story conservatives had been telling for years—of an America made up of makers and takers—or they at least recognized that as the framework within which they had to work, in order to sell their policies to the American people. Clinton is perhaps the best example, famously declaring “the era of big government is over.”

That it took Democrats until 2018 to start seriously conceiving of a new narrative about who they are and what they stand for owes much to a cottage industry of books published in the early 2000s, predicting the collapse of the Republican Party as its older, white demographic died off. These books, perhaps unintentionally, convinced party power brokers they didn’t need to create a narrative to compete with conservatives because they could win on demographics alone.

Hillary Clinton’s defeat ended that dynamic. No matter their motives, both of the upstart candidates, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, fueled their supporters with powerful stories of what America should be, in contrast to what it currently is. Their popularity is instructive.

The current crop of Democratic candidates is haltingly advancing a new narrative. Some of it recalls the New Deal. Many of the candidates this fall support busting up monopolies and taking on the power of corporate interests. They talk of a living wage and jobs for all Americans. But they are also advancing a new tale that recaptures the language of patriotism that Democrats neglected amid the counterculture upheaval of the 1960s and finally ceded to Republicans during the Reagan years. Then, patriotism centered around the image of a maverick individual soldier fighting communism. Now it’s built around service, community, and family loyalty.

Women are often the ones using this new definition of patriotism. A powerful campaign ad by former Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath of Kentucky focuses on Republican plans to gut health care and vows to “take back our country for my kids and yours.” Texas candidate Mary Jennings Hegar, an Air Force veteran, highlights her service in Afghanistan and rails against the incumbent congressman for working for big donors rather than constituents who have sacrificed for their country and want a level playing field. It is a call for service above self, country above party.

The Trump administration is making it easier for Democrats to construct this new patriotism. The president has said that he needs to save “the big, fat, sloppy United States,” calling the country “foolish” and the site of “carnage.” He has sided with the Russian government over his own intelligence community, and his party’s leaders have cozied up to Russian spies. All this gives Democrats an opening to claim that they are proudly defending the nation against a seemingly hostile president. After decades of being excoriated as un-American, they are the ones sticking up for the FBI, the CIA, the Constitution, and the rule of law. In a powerful moment in July, when Republicans killed a Democratic proposal to appropriate money for election security, Democrats on the floor of the House broke into a chant of “USA, USA!”

The idea that Democrats, rather than Republicans, are patriots has the potential to change American politics. For 50 years, Republicans argued that overwhelmingly popular Democratic programs, such as the social safety net, government regulations, and infrastructure building programs, were socialist. But if Democrats can link those programs to a new vision of what it means to be an American, they will accomplish what FDR did: not only unite the left and liberal wings of the Democratic Party, but also attract disenchanted Republicans. In July, Virginia Kruta, an editor at the conservative Daily Caller, noted “just how easy it would be” to fall for the Democrats’ message.

There is still room for Republicans to disavow Trump and to call for a society based on equal access to opportunity and equality before the law. That was, after all, the narrative of one of America’s greatest storytellers at a moment that defined patriotism, and—as the president likes to remind people—he was a Republican: Abraham Lincoln. But for now, it seems Democrats have this narrative to themselves.

In the middle of the 1970s, Zbigniew Brzezinski approached his friend, Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington, with a question: Is democracy in crisis? It was a subject of much concern at the Trilateral Commission, a kind of Rotary Club for members of the international power elite that Brzezinski had co-founded in 1973 with David Rockefeller, head of Chase Manhattan and grandson of the famous robber baron. With the Trilateral Commission’s backing, Huntington and two co-authors produced a survey of democracy’s health in the United States, Europe, and Asia. They found that faith in government had nosedived, political parties were fracturing, and efforts to pacify voters through more public spending had sent both inflation rates and deficits soaring. Too many people—Huntington’s list included “blacks, Indians, Chicanos, white ethnic groups, students, and women”—were demanding too much from politics, rendering the entire system ungovernable.

How needlessly gloomy all of this soon sounded. In 1992, Huntington’s former student Francis Fukuyama explained that the end of history had brought humanity to a “Promised Land of liberal democracy,” which offered an unbeatable combination of economic prosperity and political recognition. Capitalism and democracy fit together in a seamless whole, blocking out all other competing visions. Once intractable dilemmas of modern politics had been swept aside. The collapse of the Soviet Union had proved the bankruptcy of communism, and the taming of inflation had shown that democracies could manage their internal economic affairs. Even Huntington joined in the optimistic mood, writing a much-discussed work on a “third wave” of democratization that, beginning in the 1970s, had taken more than 60 countries from authoritarianism to democracy. The crisis was over, seemingly for good.

Today, of course, despair is back in style. The percentage of people who say that living in a democracy is “essential” has declined, and polls show rising support for nondemocratic forms of government, from technocracy to military rule. An international populist revolt has turned the previously unthinkable—from Britain exiting the European Union to Donald Trump entering the White House—into the new normal. This is a crisis that, provoked by the right, has so far been theorized by the center-left in gloomily titled books ranging from Madeleine Albright’s Fascism: A Warning to Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die, both New York Times best-sellers.

Now two more books have arrived with cases that hover between cautious optimism and measured despair: Cambridge political theorist David Runciman’s How Democracy Ends and conservative pundit Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West. Goldberg’s book has been taken up in the beleaguered ranks of the intellectual right as one of the best explanations the movement has for the rise of Trump. Runciman, on the other hand, is too idiosyncratic a thinker to belong to any tribe except the professoriate. Both authors came of age in the 1980s—Runciman was born in 1967, Goldberg in 1969—and made careers in the long 1990s, that period between the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the financial crisis of 2008. Dire warning about democratic crisis belonged to their childhood, and so did radical challenges to the political system. Intellectual maturity required putting away juvenile delusions—until, suddenly, maturity itself seemed like the delusion.

In their own ways, both push against the conventions of the emerging literature on democracy’s latest breakdown, which has tended to speak in earnest tones of endangered norms and existential threats to the republic. In other ways, they remain trapped in the mental world of the long ’90s, when pragmatists were supposed to limit themselves to tinkering with the status quo—a way of thinking that helped produce today’s populist revolts in the first place. Yes, democracy is again in crisis. But in every democratic crisis lies a political opportunity.

One of the many virtues of How Democracy Ends is Runciman’s insistence that talk of impending doom is almost certainly overblown. “The crisis is real,” he notes, “but it is also a bit of a joke.” Runciman is an inveterate contrarian who has no patience for the melodrama of the Resistance. Trump is not Hitler, and a fascist coup is not lurking around the corner. The true danger is much more banal. “Mature, western democracy is over the hill,” he writes. If this is a crisis, it’s a midlife crisis. Democracy’s best days are behind it. The great battles of the last century—expanding universal suffrage, extending civil rights, establishing the welfare state—have been won. Yet people are still unsatisfied, and Runciman sees no plausible way to restore their lost faith.

When a representative democracy thrives, it does so by offering enough benefits to citizens that they are willing to overlook the system’s inevitable frustrations. Following Fukuyama, Runciman emphasizes that the rewards are both material and intangible. Higher living standards and the recognition that comes from having your vote counted are an appealing combination. Fail to deliver on either front, however, and compromise starts to look like betrayal. Fail on both counts, and the prospect of abandoning democracy becomes increasingly attractive. This will be especially true in countries with shallow democratic traditions and lower living standards. The less a nation has to lose, the easier it is to make this switch.

The question is what system to switch to. Democracy’s advantage in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse was that it appeared to have proven itself the least bad of the available options. According to Runciman, this is no longer the case. What he calls “pragmatic twenty-first-century authoritarianism” has found a new way of satisfying demands for economic prosperity and political recognition. Compare authoritarian China with democratic India. Today, China’s per capita GDP is nearly five times higher than India’s, its poverty rate is half as large, and the average person’s lifespan is longer. As for political recognition, there’s the pride that comes from being part of a nation whose success is envied around the world. Whether the balance the Chinese government has struck is sustainable remains to be seen, but, for now, young democracies with low standards of living have an attractive alternative to consider.

For the mature and wealthy democracies of Western Europe and the United States, Runciman believes, the future holds the same fate that awaits most of us: death from old age. “Democracy could fail while remaining intact,” he writes. Even as governments deliver fewer gains, the political systems in such countries are too entrenched, populations too old, and economies too robust for the system to collapse outright. Instead, a long period of decline, during which institutions perform just well enough to avoid catastrophe, is the most likely outcome. Slowly, something new will emerge. It might still be called democracy, if the brand is worth preserving. In reality, it will bear as little resemblance to what we understand as democracy today as our system does to Athens in the time of Pericles.

The shape of this new order, Runciman argues, will be determined by future technological revolutions whose contents are today unknowable. “Mark Zuckerberg,” he writes, is “a bigger threat to American democracy than Donald Trump.” Politicians will continue to promise transformative change, but real authority will devolve to experts tasked with managing the technical problems facing a modern society, and individuals will find meaning in private communities isolated from the larger public. Imagining the system that gives full expression to these tendencies—he calls the first “solutionism” and the second “expressionism”—Runciman allows himself a rare moment of nostalgia for what will be lost. “The institutions we need to confront the political emptiness we increasingly feel,” he writes, are being hollowed out. The demos will be too splintered to exercise its will, and even if voters somehow united, they wouldn’t know what to do.

Beyond this, Runciman has few predictions to make. Pick a scholarly discipline, and he can give a good reason for questioning its value in navigating the present. The social sciences can tell us everything and more about the intricacies of our political system but precious little about how the enterprise as a whole hangs together. History is just as duplicitous a guide, filled with misleading parallels that lead us to assume we know more about how the future will play out than we do. Yet his own accounts of pragmatic authoritarianism and unchained technocracy have a distinctly early-twentieth-century flavor to them, back when political visionaries foresaw the dawning of a reign of engineers. As Runciman noted in his last book, The Confidence Trap, a more sanguine study of democracy published in 2013, this earlier bout of pessimism gave way to yet another period in which democracy’s triumph seemed unassailable, until the onset of the Cold War caused another crisis of faith. The case for optimism is easy to make in good times, and when conditions are dire, nihilism looks like prudence.

Even if his vision of the future comes to pass, there’s something unsatisfying about Runciman’s refusal to speculate on what might be done to avoid the dreary scenario he conjures. He could be right that in the long run democracy is doomed. But as his Cambridge predecessor John Maynard Keynes noted, in the long run we are all dead. It would help to have a little more guidance in the meantime.

Jonah Goldberg is not nearly so reluctant to weigh in. There is no purer representative of the modern conservative intellectual than Goldberg, senior editor at National Review; regular contributor to Fox News; and fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he holds a chair endowed by hedge fund billionaire Cliff Asness. Shaped by the intellectual movement that developed around William F. Buckley Jr. in the middle decades of the twentieth century, he is a believer in the efficiency of markets, the wisdom of tradition, and the dignity of bourgeois virtues.

Around National Review, this synthesis of moral conservatism and economic libertarianism was known as fusionism, and today Goldberg is its most forceful defender. From justifying the war in Iraq to championing the Tea Party, he has been a reliable voice from the right, usually with a nod to the conservative canon and a decades-old pop culture reference that allows him to gin up a few hundred words on the radicalism of Dead Poets Society or the insights of Groundhog Day.

Goldberg made his most significant contribution to the movement in 2008, with the publication of his first book, Liberal Fascism, which claimed that contemporary liberalism was, if not fascist, then at least fascism’s “well-intentioned niece.” “I have not written a book about how all liberals are Nazis,” he wrote, in a work whose cover featured a smiley face with a Hitler mustache. But he did write a book arguing that fascism and Progressivism were united by their rejection of laissez faire, making it possible for him to place Hillary Clinton in an intellectual tradition that reached back to Benito Mussolini. This thesis outraged liberals and historians—categories with significant overlap—but the book was a more interesting failure than its critics admitted, and Goldberg was right to draw attention to often neglected aspects of American history, including the importance of eugenics to Progressives and the scale of the domestic repression imposed by Woodrow Wilson’s administration during World War I.

The book was a hit, peaking at number one on the New York Times best-seller list and solidifying Goldberg’s position in the conservative media hierarchy. Then came Trump. Like many other conservatives, Goldberg supported much of Trump’s agenda, including a border wall, which he had been calling for since 2006. But he saw Trump himself as a walking insult to the American right. “Conservatives have spent more than 60 years arguing that ideas and character matter,” he wrote in the fall of 2015. “That is the conservative movement I joined and dedicated my professional life to,” and it had no place for figures like Trump.

In 2016, he learned that most conservatives had signed up for a different movement. Shortly after Ted Cruz dropped out of the primaries, Goldberg informed participants in a National Review cruise along the Danube that he still could not support the presumptive Republican nominee for president. “When I announced on the boat that I would never vote for Trump,” he recalled, “many in the audience gasped.” Trump noticed Goldberg’s criticism, writing in his campaign book, Crippled America, of the “truly odious” commentator being his “usual incompetent self.” Goldberg has kept up the fight since Trump has taken office, rarely objecting to the administration’s policies but always ready to spar with Sebastian Gorka on Twitter. That’s been enough to earn him the contempt of the president’s loyalists and a strange new respect from the liberal media.

Suicide of the West is Goldberg’s reckoning with the long road that has led to now. Whereas Liberal Fascism offered a mishmash of political and intellectual history, his latest book is more a work of pop-historical sociology, with doses of economics, anthropology, and psychology thrown in for good measure, all presided over by the spirit of Friedrich Hayek. Reflections on everything from the torture practices of the Assyrians to Japan’s most recent Godzilla movie sprawl across its 464 pages. Buried amid the plot summaries of Mr. Robot and block quotes of Woodrow Wilson is a simple argument: Liberal capitalism has brought unprecedented prosperity but is perennially in danger because it runs counter to an unchanging human nature.

At the core of Goldberg’s narrative is an event that he, borrowing from the philosopher and anthropologist Ernest Gellner (described here, weirdly, as a historian), called “the Miracle.” Once upon a time, the story goes, the overwhelming majority of humanity lived in grinding poverty. That time lasted from before recorded history up to the eighteenth century, when a small but increasing proportion of the population began to experience sustained economic growth. The result is that today billions of people live longer, healthier lives than would have been imaginable before the Miracle. Scholars disagree over the timing of this shift, but, give or take a century, Goldberg’s story checks out. We take economic growth for granted today and lament when it clocks in at a measly 1 percent, but even that is a profound departure from the historical norm.

According to Goldberg, there’s a good reason for the Miracle’s late arrival. Humans are tribal creatures by nature, built to live in small groups that fear the unknown. The emergence of modern economic growth required an intellectual revolution that ran counter to all of this. It put respect for free markets (capitalism) and individual rights (classical liberalism) at the center of society, challenging instincts hardwired into humanity’s collective unconscious by some 250,000 years of evolution. The human species is old, the Miracle is new, and the two have not yet come into alignment. This is where the “suicide” of the book’s title—borrowed from the conservative philosopher James Burnham’s 1964 work of the same name—enters the picture. Populism, nationalism, and identity politics are ways our tribal nature rebels against the liberal capitalist order. Turn away from the Miracle, Goldberg warns, and humanity will return to the squalor and misery that is our natural condition.

Nothing in this account of liberal capitalism requires the presence of democracy. In eighteenth-century England, which Goldberg treats as the site of the Miracle’s first appearance, fewer than one in five men had the right to vote. Not until 1918 did all adult British men win suffrage, and not until 1928 did women join them. Liberal capitalism might be desirable, but it is not necessarily democratic. Historically, the two were more likely to be seen as antagonists than allies. That’s certainly how Hayek understood them, and he put liberal capitalism first. So, in the past, has Goldberg. “I’m in the camp,” he wrote for National Review in 2006, “which holds that liberalism is more important than democracy.... I mean liberalism in the classical or philosophical sense: rule of law, individual liberty, free markets, free expression, etc., etc. Lost on many people is the fact that these things don’t necessarily come with democracy. Indeed, democracy can often take these things away.”

The case for optimism is easy to make in good times, and when conditions are dire, nihilism looks like prudence.Goldberg places the blame for democracy’s most recent attempt to “take these things away” squarely on the left. Suicide of the West is preoccupied with the influence of what could be called Social Justice Inc. His taxonomy of this group includes not just the tenured radicals who so often feature in right-wing polemics, “but also diversity consultants, administrators, and various outside activist groups,” all of whom “have a vested interest in heightening racial and sexual grievances for the simple reason that they make a living from such things.” This is Goldberg the Nietzschean, who sees left-wing radicals concealing their will to power underneath bromides about making a better world. Barack Obama is his leading representative of this group. “He is part of an entire social and psychological movement that basically says the sort of white middle-class majority that ran this country for a very long time is the problem,” Goldberg told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt in the spring of 2016.

Which, according to Goldberg, brings us to Trump. “Trump is,” he explained to Hewitt, “a response to the sort of bile that I think Obama has injected into the American politics.” Trumpism, too, in Goldberg’s view, is not merely “an alternative to the worst facets of progressivism” but “a new right-wing version of them.” He attributes this mutation to the failure of the Tea Party. In his telling, the Tea Party began as an authentically conservative movement dedicated to limiting the size of government, paying down the deficit, and respecting the Constitution. (“I spoke to many of their rallies,” he notes.) Then the social justice warriors got to work. “What turned so many Tea Partiers into tribalists,” he argues, was the experience of being “demonized by the media and Hollywood as racist yokels and boobs.” Out of frustration, they succumbed to the eternal lure of the tribe and decided that the time had come to Make America Great Again. And so, thanks to both the provocations of the left and the clash between human nature and liberal capitalism, the right turned to Trump.

That’s one version of the story, and I’m sure it tracks with Goldberg’s personal experience. He was the one speaking at the rallies. But it doesn’t seem like he did a good job listening. After conducting interviews with Tea Party members, political scientists Vanessa Williamson, Theda Skocpol, and John Coggin concluded that, while Tea Party members did support deficit reduction and cuts to government spending, the movement was powered by the sense that an unaccountable political elite was showering undeserving freeloaders with money taken from the taxes of hard-working Americans. They loved big government when it benefited them, especially Social Security and Medicare. But the issue that provoked the strongest emotional reaction was immigration, which was just one part of a thorny tangle of questions related to race. Polls of Tea Party members revealed high levels of racial resentment: According to one survey, 59 percent weren’t confident that Barack Obama was born in the United States. “I just can’t relate to him,” one Tea Partier said of Obama. But they could relate to a billionaire reality star who said exactly what they wanted to hear.

These tendencies go back much further than the Tea Party, and so do the origins of Trumpism. Goldberg needs a sweeping theory of modernity to justify his claim that Donald Trump’s rise is a rupture in the conservative tradition. A simpler story would begin by acknowledging that mobilizing the resentments of white voters against both racial minorities and cultural elites has been an essential strategy for the modern right from the days of Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon up to the present. More recently, the right-wing infotainment machine—Fox News, talk radio, and the online opinion swamp—turned a political project into a profitable business. It also made minor celebrities out of figures like Goldberg, self-proclaimed guardians of true conservatism who fancied themselves warriors in a battle of ideas. Now it’s found suppliers who better understand their audience.

Like Runciman, Goldberg has emerged from his ruminations with a melancholy outlook on the future. “I haven’t felt this kind of alienation from politics in a very long time,” he wrote during the book tour for Suicide of the West. “It’s not disgust so much as a kind of exhaustion.” Exhaustion is a good term for the impression Runciman conveys, too, though in his case it’s the weariness of the perpetual cynic bemused at the naïveté of the innocents who buy into what he calls the “empty promises” of modern politics. It’s also a fair description of the entire crisis-of-democracy literature, in which the warnings about imminent disaster ring with clarity but the obligatory summons to a better tomorrow come out in a mumble.

By 2021, the blandest of Democrats could be in control of government, and pundits could be heralding the revenge of the norms.Today’s populist fever could soon break. By 2021, Trump could be working in real estate full-time again, the blandest of Democrats could be in control of government, and pundits could be heralding the revenge of the norms. But it’s also possible that a more profound shift is underway. As the political theorist Corey Robin has observed, when an old order is collapsing—whether it’s New Deal liberalism in the 1970s or Reaganite conservatism and Clintonian neoliberalism today— it is easy to confuse the waning of a particular political system with a more fundamental breakdown of democracy. Just as Huntington’s world gave way to Fukuyama’s a generation ago, democracy’s latest crisis opens the way for a new kind of politics.

Lately, a single day’s news can offer glimpses of both the worst and best futures: The Supreme Court rules in favor of the White House’s travel ban in the morning, and at night Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez topples a pillar of the Democratic establishment. A revanchist conservatism fueled by white nationalism waits on one side, and a left committed to reviving socialism for the twenty-first century lies on the other. For now, the scales are weighted clearly in favor of the right. But as defenders of normalcy have learned in the last two years, nothing lasts forever.

American democracy might have entered its golden years, but new blood is rejuvenating it every day—including next January 3, when Ocasio-Cortez will become the youngest woman ever to serve in Congress. For all Goldberg’s emphasis on an unchanging human nature, he misses one of its most important features: To each new generation, yesterday’s hard-won victories are just another part of the world as they have always known it. That refusal to be dazzled by old achievements is what makes progress possible. And it just might save democracy. Today, the suicide Goldberg warns against is one potential outcome, even if a remote one; the senility Runciman predicts is an option, too, maybe a likely one. But a third prospect is coming into sight: rebirth.

Germany was supposed to be a model for solving global warming. In 2007, the country’s government announced that it would reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by the year 2020. This was the kind of bold, aggressive climate goal scientists said was needed in all developed countries. If Germany could do it, it would prove the target possible.

So far, Germany has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 27.7 percent—an astonishing achievement for a developed country with a highly developed manufacturing sector. But with a little over a year left to go, despite dedicating $580 billion toward a low-carbon energy system, the country “is likely to fall short of its goals for reducing harmful carbon-dioxide emissions,” Bloomberg News reported on Wednesday. And the reason for that may come down not to any elaborate solar industry plans, but something much simpler: cars.

“At the time they set their goals, they were very ambitious,” Patricia Espinosa, the United Nations’ top climate change official, told Bloomberg. “What happened was that the industry—particularly the car industry—didn’t come along.”

Changing the way we power our homes and businesses is certainly important. But as Germany’s shortfall shows, the only way to achieve these necessary, aggressive emissions reductions to combat global warming is to overhaul the gas-powered automobile and the culture that surrounds it. The only question left is how to do it.

In 2010, a NASA study declared that automobiles were officially the largest net contributor of climate change pollution in the world. “Cars, buses, and trucks release pollutants and greenhouse gases that promote warming, while emitting few aerosols that counteract it,” the study read. “In contrast, the industrial and power sectors release many of the same gases—with a larger contribution to [warming]—but they also emit sulfates and other aerosols that cause cooling by reflecting light and altering clouds.”

In other words, the power generation sector may have emitted the most greenhouse gases in total. But it also released so many sulfates and cooling aerosols that the net impact was less than the automobile industry, according to NASA.

Since then, developed countries have cut back on those cooling aerosols for the purpose of countering regular air pollution, which has likely increased the net climate pollution of the power generation industry. But according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, “collectively, cars and trucks account for nearly one-fifth of all U.S. emissions,” while “in total, the U.S. transportation sector—which includes cars, trucks, planes, trains, ships, and freight—produces nearly thirty percent of all US global warming emissions ... .”

In fact, transportation is now the largest source of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States—and it has been for two years, according to an analysis from the Rhodium Group.

Rhodium Group

Rhodium GroupThere’s a similar pattern happening in Germany. Last year, the country’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased as a whole, “largely thanks to the closure of coal-fired power plants,” according to Reuters. Meanwhile, the transportation industry’s emissions increased by 2.3 percent, “as car ownership expanded and the booming economy meant more heavy vehicles were on the road.” Germany’s transportation sector remains the nation’s second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, but if these trends continue, it will soon become the first.

Clearly, the power generation industry is changing its ways. So why aren’t carmakers following suit?

To American eyes, Germany may look like a public transit paradise. But the country also has a flourishing car culture that began over a hundred years ago and has only grown since then.

Behind Japan and the United States, Germany is the third-largest automobile manufacturer in the world—home to BMW, Audi, Mercedes Benz, and Volkswagen.* These brands, and the economic prosperity they’ve brought to the country, shape Germany’s cultural and political identities. “There is no other industry as important,” Arndt Ellinghorst, the chief of Global Automotive Research at Evercore, told CNN.

A similar phenomenon exists in the United States, where gas-guzzlers symbolize nearly every cliche point of American pride: affluence, capability for individual expression, and personal freedoms. Freedom, in particular, “is not a selling point to be easily dismissed,” Edward Humes wrote in The Atlantic in 2016. “This trusty conveyance, always there, always ready, on no schedule but its owner’s. Buses can’t do that. Trains can’t do that. Even Uber makes riders wait.”

It’s this cultural love of cars—and the political influence of the automotive industry—that has so far prevented the public pressure necessary to provoke widespread change in many developed nations. But say those barriers didn’t exist. How could developed countries tweak their automobile policies to solve climate change?

For Germany to meet emissions targets, “half of the people who now use their cars alone would have to switch to bicycles, public transport, or ride-sharing,” Heinrich Strößenreuther, a Berlin-based consultant for mobility strategies told YaleEnvironment360’s Christian Schwägerl last fall. That would require drastic policies, like having local governments ban high-emitting cars in populated places like cities. (In fact, Germany’s car capital, Stuttgart, is considering it.) It would also require large-scale government investments in public transportation infrastructure: “A new transport system that connects bicycles, buses, trains, and shared cars, all controlled by digital platforms that allow users to move from A to B in the fastest and cheapest way—but without their own car,” Schwägerl said.

One could get away with more modest infrastructure investments if governments required carmakers to make their vehicle fleets more fuel-efficient, thereby burning less petroleum. The problem is that most automakers seek to meet those requirements by developing electric cars. If those cars are charged with electricity from a coal-fired power plant, they create “more emissions than a car that burns petrol,” energy storage expert Dénes Csala pointed out last year. For such a switch to actually reduce net emissions, the electricity that powers those cars must be renewable.”

The most effective solution would be to combine these policies. Governments would require drastic improvements in fuel efficiency for gas-powered vehicles, while investing in renewable-powered electric car infrastructure. At the same time, cities would overhaul their public transportation systems, adding more bikes, trains, buses and ride-shares. Fewer people would own cars.

At one point, the U.S. was well on its way toward some of these changes. In 2012, President Barack Obama’s administration implemented regulations requiring automakers to nearly double the fuel economy of passenger vehicles by the year 2025. But the Trump administration announced a rollback of those regulations earlier this month. Their intention, they said, is to “Make Cars Great Again.”

The modern cars they’re seeking to preserve, and the way we use them, are far from great. Of course, there’s the climate impact—the trillions in expected economic damage from extreme weather and sea-level rise caused in part by our tailpipes. But 53,000 Americans also die prematurely from vehicle pollution each year, and accidents are among the leading causes of death in the United States. “If U.S. roads were a war zone, they would be the most dangerous battlefield the American military has ever encountered,” Humes wrote. It’s getting more dangerous by the day.

*Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Germany is home to Chrysler, the car company.

We already know much of the story that Adam Tooze tells in Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World, his ambitious study of the causes and effects of the financial meltdown that caused the Great Recession. The opening pages of his book recount the events of September 16, 2008, “the day after Lehman.” In a matter of hours, the Dow Jones plummets “778 points, wiping $1.2 trillion off the value of American businesses.” The entire financial system begins to unravel and it becomes clear that the mortgage-based CDOs and credit default swaps that underpinned world banking are nearly worthless. Mutual funds pull back from investing and banks face an immediate shortage of funding. World lending begins to freeze altogether. European countries face capital shortages. The entire world economic system is on the edge of collapse.

But Tooze is not simply telling a story of the financial crisis. Crashed is also the tale of the political intricacies of the crash, the ensuing bailout, and of the great political unraveling that has followed. He documents the descent into recession in 2008 as housing values plummeted and the average net worth of the middle class American household halved from $107,000 to $57,800 in a year. American car sales came to a near halt, sending a reaction through the global manufacturing chain. Chrysler and General Motors teetered on bankruptcy; Mexico, a major center in North American car manufacturing, reeled as its non-petroleum exports dropped by 28 percent and its GDP contracted 7 percent over the year. By 2009, the crisis had spread worldwide, with Germany’s exports falling 34 percent. GDP dropped around the world and a credit crunch caused poorer, over-indebted European nations like Portugal and Greece into virtual bankruptcy.

Although the bailout of American investment banks prevented total world economic meltdown, it did not instill the public with trust in the government or institutions. Their failure to prevent massive declines in the standard of living would discredit establishment politicians on both the center left and right. Whereas average citizens lost huge chunks of their wealth and buying power, the banks got a bailout and the people responsible for the crisis walked away, not only without jail time but, in many cases, with handsome golden parachutes, funded by taxpayer money.

What looked like an American mortgage debacle ended up as a world financial crisis that has shaken the foundations of liberal democracy from Washington and Rome to Istanbul. Tooze shows the global nature of financial and political breakdowns, which have otherwise been linked to local factors. Although it is a stretch to compare Turkey and former eastern bloc countries to the UK, the US and Italy—where liberal democracy is under attack, but has not yet ceased to function—what this book makes clear is that one more crash could very well be the tipping point for Western democracy.

A scholar of early twentieth century European economic history, Tooze has chosen here to write a history of the recent past on a global scale. To regular readers of the Financial Times, or of IMF, OECD, World Bank, and European Commission reports, most of the details in this book will be familiar. But it is the configuration of Tooze’s analysis that is novel—he darts from the crisis in Washington to monetary politics in Europe, and on to Chinese fiscal policy to explain how interconnected each of these countries’ economies are. This sends a clear message to those who believe in nationalist economic policies: We are all in this together, to a greater extent than financial institutions and governments have made clear.

Many see the origins of 2008 in America’s deregulated and undercapitalized banks. There is no question that they created a mortgage crisis that morphed into a financial crisis as toxic subprime CDOs—a financial product of mortgage, mortgage insurance, and bonds pooled together as collateral for the product itself—became worthless. American banks were overleveraged at 20:1 in subprime assets, which means that for every 20 dollars of risk investment, they held, by US law, only one dollar of actual capital guarantee. But, Tooze seeks to demonstrate, the crash was not solely about the United States; it was an international phenomenon.

The American financial playing field, he shows, was designed in great part by Europeans in the 1980s. When German, Swiss, French and Dutch banks began to buy into the city of London as a “springboard” to US markets, they also developed and spread the dangerous CDO products. And, as the economists Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig have long shown, European banks were even more undercapitalized than the Americans with Deustchebank, UBS and Barclays averaging 40:1 risk exposure. Tooze makes a convincing case that the crash came from a failure of international regulation and the lack of political will to limit a dangerous system of financial risk.

Tooze is careful to show that the crash was not simply the fault of banks and regulators. National governments also flouted financial responsibility at every level. Starting in 1995, many European countries began an unsustainable borrowing spree that began in 1995 and continues to this day in the US, Europe and beyond. As Tooze shows, debt-to-GDP ratios have skyrocketed in Europe. In Spain, Portugal and Greece debt went from the EU stipulated maximum of 60 percent of GDP to well over 100 percent. The same was happening in Italy and France, and indeed, the US and Japan. This meant that even major countries could not, and still cannot, realistically pay off their debt.

What Tooze does not say is that most countries are much poorer than they think they are. They face the daunting challenge of somehow convincing their publics to cut spending and raise taxes or face downgrades, defaults and more financial crises. The likelihood of future crashes may be even greater than he suggests.

Tooze’s most insistent point is that the 2008 crash created the conditions for “illiberal democracy.” The success of the Tea Party and the American far-right, he argues, grew directly from it: Once George W. Bush, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke realized that they needed to spend $700 billion to nationalize the American financial system, their own party revolted against them. Most Republicans flatly rejected the bailout and refused to vote for it. Of the 205 votes in favor of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, “140 came from the Democrats and only 65 from the Republicans. Of those opposed, 133 were Republicans and 95 Democrats.” These facts are worth revisiting, because, as Tooze tells it, those who refused to vote for TARP would pave the way for the reactionary House Freedom Caucus that has steadfastly stood by Donald Trump.

The links between the financial crisis and the rise of neo-fascism in Hungary and Poland are similarly clear. Both countries had entered European capital markets not with the euro but with their old currencies, the forint and the zloty. Vulnerable and small, Hungary had taken much of its national and household debt in Swiss francs. As the forint collapsed and the franc grew in the wake of the crisis, Hungary and its companies and homeowners found themselves nearly ruined by far-away forces that made their debts untenable. Hungary was “humiliated” by favorable but intrusive IMF and EU loan assistance, which many in Hungary thought made Hungary a colony of the EU and interests of international capital.

To nationalists and those who lost their savings and houses, it was reminiscent of the Trianon Treaty of 1920, which saw the big powers of Europe amputate 70 percent of Hungary’s landmass and 75 percent of its population. The far-right Fidesz party, led by Victor Orbán, used anti-Semitic specters of foreign bankers and Jewish conspiracies bringing down Hungary, and set up a home base for what is politely known today as the alt-right. Poland followed suit, though later, with its own shift to Catholic, authoritarian nationalist government.

Of course this does not explain why hard-hit countries such as Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece did not turn to extreme reactionary governments. Italy re-elected Silvio Berlusconi in 2008, and in 2011 elected a series of moderate center and center-left governments, only voting in a nationalist, xenophobic, pro-Russian government this year, after a long simmering migration crisis. Meanwhile, Spain and Portugal have opted for traditional, moderate parties, and Greece chose the democratic socialism of Syriza. Tooze leaves unanswered the question of why the crash pushed some countries to a threshold of intolerance and authoritarianism while others have so-far resisted. Nor does he explore the possibility that the crash only exacerbated existing tendencies, rather than wholly reshaping the politics of the countries hit hardest.

Tooze is a master of the modern financial report and his book is built on a dizzying array of expert reports, studies and Financial Times and Economist articles. He is the financial reader’s reader. But this poses some issues: He often enthusiastically follows the official accounts of the most famous leaders, press releases and reports from the OECD, the IMF, the World Bank and the credit ratings agencies. By sticking to the official lines and citing usually the most glamorous figures, he can overlook the fine grain of what actually happened.

Take for example his reading of former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’s telling of the Greek debt crisis. Varoufakis claimed that the Germans had offered Greece unsustainable debt and publicly humiliated and crushed the country. Few can argue with that. But Tooze never mentions Varoufakis’s disastrously undiplomatic insistence on calling creditors immoral during negotiations (Greece too had its share of blame in the crisis), revealing the closed discussions, violating rebate agreements, and attacking creditors, while threatening to pull out of the monetary union. It served instead to spook creditors and the markets, and to cause a bank run, capital controls, and the loss of tens of billions of euros from the already bankrupt Greece. By treating sources like Varoufakis uncritically, Tooze simply misses the real story.

Alan Greenspan, Larry Summers, Hank Paulson and George W. Bush—who gutted the SEC—are portrayed as cool and potentially heroic decision-makers in the face of crisis.Tooze’s account of German economic policy is also relatively superficial, relying on sources such as “the official chronicle of the German finance ministry” and a small sample of news articles. He does not compare various arguments or versions of what happened. This means that rather than critical analysis, we get instead an anodyne summary. Tooze rightly recognizes that Germany’s loans to Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain helped stabilize German export markets. What he does not say is that while claiming to be a victim of Greece’s profligacy, Germany benefitted from the Greek and southern European debt crisis to an extent that some might find morally dubious.

By causing chaos and uncertainty in the Eurozone, the Greek crisis lowered the value of the euro, and ostensibly allowed over-indebted southern European countries to borrow more at lower cost so they could afford to buy more German goods, which propped up German industry. All the while, this drove down Germany’s own interest rates in relation to other countries, allowing them to undercut Italian and French firms, while, at the same time, snapping up Greek assets for next to nothing, and profiting from Greek interest payments to help their own struggling banks. This is the kind of information one can dig out of a critical analysis of the sources, but it requires a willingness to question many of the Olympian authorities on which Tooze relies. That willingness is essential in the difficult historical process of assessing testimony.

In the end, Tooze does not give a clear sense of exactly who caused the crisis. Even Alan Greenspan, Larry Summers, Hank Paulson and George W. Bush—who gutted the SEC and made it even harder to see and manage potential fraud and crisis—are portrayed as cool and potentially heroic decision-makers in the face of crisis. Avoiding any specific criticism, Tooze, for the most part, constructs a play-by-play narrative. The same is true when he looks to the future: He rightly warns that national hubris in China could be the source of the next crisis, but has little more to say about who might contribute to this or how.

By his account, we are powerless to control the invisible hand of the global financial system that will bring us another crisis, and we can only react, as Paulson did. “These crises are hard to predict or define in advance,” Tooze writes,

They are not anticipated and often deeply complex … And they demand action. It is this juxtaposition that frames the narrative of this book: large organizations, structures and processes on the one hand; decision, debate, argument and action on the other.

There is truth in his depiction of the unwieldy behemoth of global finance. And yet, we know the culprits in this story: investment banks, those who are supposed to regulate them, and the states that take unmanageable debt. We also know that good, unbiased financial auditing is an old and effective tool for measuring risk, debt and capitalization, as are good public financial management and well-designed financial regulations, which were peeled away from the 1990s onwards. As powerless as one might feel, jail time for bankers guilty of misconduct is a deterrent that has not yet been tested. It might just work.

Indeed, Tooze’s book makes it clearer than ever that effective regulation is needed. In this light, the recent bi-partisan repeal of the Dodd-Frank Act, created to reign in many of the excesses that caused the crash, looks all the more ominous. And while China risks an unforeseen crisis, Tooze suggests that stable and well-capitalized banks would be more able to weather another crash. Our future is not completely decided by an irrational market. Yet a public that no longer believes in the law’s capacity to protect it from the market will turn to terror, autocracy and technocracy over democracy. That is a chilling and convincing conclusion.

When the tanks of the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact nations rumbled into Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968, Czech philosopher Ivan Sviták had a fateful decision to make.

Support for gradual reform of Czech Communism had emerged within the ranks of the party itself in 1968. But the profound policy shift proved difficult for the state to manage. Czechoslovakia’s communists were caught between demands for wider and speedier democratic transformation from the country’s citizens, and the determination of the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact states to reverse these reforms entirely.

As a professor of philosophy at Prague’s Charles University, Sviták had helped shape public thinking about reform, his writings and lectures growing increasingly bold over its twelve years of development. By March 1968, Sviták was calling for a complete renovation of Czechoslovakia’s communist system.

“Our achieving democratic socialism is contingent upon the liquidation of the mechanisms of totalitarian dictatorship and the totalitarian way of thinking,” he wrote in one of his published lectures, advocating “free press and public opinion.”

Sviták’s notoriety reached such dimensions in that heady spring that the radical French students who occupied the Sorbonne sent him a telegram with their “fraternal greetings” at the height of the tumult in Paris in May 1968. But the philosopher also became a key target of the forces of reaction inside and outside the country.

As Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia to stop the so-called Prague Spring in its tracks, Sviták was attending a conference in Vienna. His choice was a stark and simple one: Stay or go back. He chose to stay in the West—at least “until the occupation was over,” as he told The New York Times in September 1968.

Less than a month after the invasion, Sviták was already a fellow at Columbia University, moving in a position arranged for him by Zbigniew Brzezinski. (The Times also reported that he’d had his briefcase and passport stolen as he slept in a Manhattan hotel. Welcome to America.)

Sviták was much in demand in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s intervention. He was quoted widely in Western media outlets, and he published two books: Man and His World: A Marxian View and The Czechoslovak Experiment 1968-1969.

It took little over a year for the country’s hardline communists to reassert totalitarian rule and suffocate reforms in a grim spectacle referred to as the “normalization.” Sviták’s notoriety (and audience) faded. The dissidents who did stay behind, most notably playwright and future president of Czechoslovakia Vaclav Havel, pushed to the forefront of the public imagination in the 1970s and 1980s.

Sviták ended up teaching at California State University, Chico, a place he jokingly dubbed “Chico-Slovakia.” In a 1988 profile in the New York Times, he quipped: ‘’I didn’t go to jail. I went to the California State University instead.’’

The Velvet Revolution opened the door for Sviták’s return in 1989. And in the five years before his death from cancer in 1994, Sviták was once again a voice of opposition, finding himself with very strange bedfellows.

Upon his return, Sviták felt a deep revulsion for the neoliberal forces unleashed in Czechoslovakia after the end of totalitarian rule. It was a tide of revanchism and privatization (and, in some cases, plunder) led by the country’s prime minister and future president Vaclav Klaus, who styled himself after British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Sviták’s response was not only expressed in furious polemics with the new leaders, including his former dissident comrade and new Czechoslovak president Havel, but also in a return to active politics. Sviták contested – and won – a seat in Czechoslovakia’s Federal Assembly in 1992 as part of a broad coalition of leftist forces (“Levy Blok”), spearheaded by the reconstituted remnant of the country’s Communist Party.

“The mainstream view on [Sviták] after 1989 was that he’d ‘gone crazy,’” Joe Grim Feinberg, a research fellow at the Czech Academy of Sciences, observed to me by email. “How could someone who was treated so badly by the Communists come back and then enter into a political alliance with them? Either he’d gone mad, or was just a dinosaur who was just too stubborn to give up on his Marxism.”

But now, according to Feinberg, who edited a 2014 volume of Sviták’s essays, a reassessment of Sviták’s legacy is well underway: “A younger generation of leftists, tired of the post-1989 anti-Communist discourse, has a lot more respect for him, seeing him as one of the few public voices to continue to maintain a critical voice, and not become a spokesman for the new powers.”

It is not only young leftists in the Czech Republic who are having a new look at Sviták. His philosophy of politics—formulated in the passions of reform and sobered by the failure of the Prague Spring—possesses a continuing richness and resonance, especially a new generation explores hybrids of the democracy and socialism Sviták sought to create in 1968, and mulls the question of when ideologies, regardless of where they sit on the left-right spectrum, become too extreme or illiberal for their original adherents.

At the root of Sviták’s work is an exuberance about human possibility, and an insistence that principle should trump party in every circumstance. Citizens who put truth at the forefront of their political sensibility and activity, he argued, possessed a unique power to reshape the world for the better.

At various moments in 1968 and 1969, Sviták wrote succinct and aphoristic “commandments” for various players in the Prague Spring and its aftermath. In a piece advising for intellectuals who had hit “rock bottom” in 1969, Sviták observed that “Life is the test of your possibilities in history, of your imagination, of your courage, of your intellect.”

Totalitarians’ contempt for truth actually reflected their deepest fears.Sviták saw the best of these possibilities as a politics that was rooted firmly in truth. Not the final truth proclaimed by ideologues, he argued, but an ongoing search and refinement. “Truth is res nullius, something belonging to nobody, precisely because it belongs to everyone who seeks it,” he wrote in 1956. “People who live in absolute certainty that they have found the truth are dangerous. They will watch the executions of heretics and criminals, because what they are watching is not an execution and a crime, but an act of justice.”

Truth—and especially political truth—has been a central concern in Czech philosophy since Bohemian religious reformer Jan Hus was burned at the stake by the Catholic Church in the 15th century. “Pravda Vítězí,” or “Truth prevails,” ascribed to Hus, is the Czech Republic’s national motto.

For Sviták, political truth was the essential weapon to fight totalitarian power, “the most dangerous enemy of any totalitarian dictatorship,” because “the absolute power of the bureaucratic elite is possible only thanks to misinformation about the conditions in which people live.” Meanwhile, totalitarians’ contempt for truth actually reflected their deepest fears. Political truth-tellers don’t even need to seek out open conflict with power, he observed in a July 1968 essay. Their mere existence is an affront to it.

Svitak’s contemporary, the more famous Vaclav Havel defined his famous concept, “living in truth,” i.e. establishing political truth, as a process requiring a carefully calibrated dance of affirmations and negations leading incrementally to political change. One must recognize that one is living a lie under totalitarianism, and refuse at a personal level to observe the forms and rituals required by unjust power. When sufficient numbers at last begin to live in this truth, and it begins to permeate society, citizens can unite collectively to negate and then overthrow totalitarianism.

But Sviták’s view of the transformative power of truth was less incremental, and less attuned to strategy. A commitment to truth, in his view, had the inherent power and purity to shake and reshape political reality. “Speak the truth regardless of tactical considerations, since concessions to tactics are concessions to truth,” he wrote only a month before the tanks arrived in Prague. “If you cannot speak the truth, be silent.” Philosophy and intellectual honesty were, for him, the equivalent of a superweapon in a guerrilla resistance war: a tool to obtain human freedom.

Yet Sviták meditated deeply on the failures of the Prague Spring. Writing twenty years after the idealist reform movement was crushed, he called it “a classic example of how literature as a substitute for politics cannot, at a critical moment, offer any alternative” to what he dubbed “professional politics.” The power of the thoughts and words must be married to the active exercise of political power. Perhaps that is part of the reason why Sviták, after his return to his homeland, sought political office and unlikely political alliances, rather than advocating from the lecture hall as he had in the sixties.

Sviták’s obstinacy in opposition did not always find favor with his contemporaries. “Basically, it seems he had an instinct to oppose anything that seemed fashionable or mainstream,” said Feinberg. “When he was criticizing Communist leaders, this made him popular. When he criticized the reform Communists for not going far enough, it was the same. When he criticized fellow dissidents and exiles, he alienated them. When he criticized the post-Communist leadership, he didn’t earn many friends.” But, Feinberg added, “Whatever personal virtues or flaws led him to take his critical stances, they were valuable stances, often taken at times when no one else was willing to take them, or to do so publicly.”

Read against our own political turmoil and possibilities, Sviták’s writings brim over with an intellectual courage and ebullience that is as vital today as it was 50 years ago. Amidst contemporary politics rife with polarization, accusations of “fake news,” and seemingly endless catalogues of presidential falsehoods, Sviták’s work reminds us that an absolute commitment to speaking the truth clearly has immense power to challenge authoritarian distortions. Yet it also reminds us that mere speaking is not enough; the truth must be wedded to concrete civic action to prevail.

No comments :

Post a Comment