Elon Musk is burnt out. He has been working for 120 hours a week, he told The New York Times in a deeply personal and occasionally alarming interview. He has not taken a week off since 2001, when he contracted malaria. Work forced him to miss celebrating his own birthday and his brother’s wedding. His friends are worried about him and he has trouble sleeping. He is obsessed with his enemies, the traders short-selling his electric car company Tesla, who have caused him “extreme torture.”

Musk’s online persona—a kind of swaggering nerd king, a subreddit come to life—is all about punching back at his critics. But in the Times interview he comes across as damaged, at the end of his rope, unsure if he can continue at the grueling pace he has set for himself, not only micromanaging Tesla through serious growing pains, but also running three other companies simultaneously. “This past year has been the most difficult and painful year of my career. It was excruciating,” Musk told the Times. “I thought the worst of it was over—I thought it was. The worst is over from a Tesla operational standpoint.” He continued: “But from a personal pain standpoint, the worst is yet to come.”

Musk’s erratic behavior has cost Tesla periodic dips in market value, though investors’ faith in the company has always led to a subsequent rebound. (Tesla’s stock fell sharply once again in response his interview with the Times.) But the interview raises serious questions about whether the tech billionaire is able to run a $50 billion company whose value is largely predicated on the vision of its idiosyncratic owner.

Tesla has come under scrutiny in recent months, thanks to its negative cash flow, production problems, and high-profile crashes of its semi-autonomous cars. Musk has been very open about how stressful it has all been. He has taken to sleeping in the factory producing Tesla’s Model 3 in an effort to boost production. Nervous about profitability, he laid off 9 percent of the company’s workforce in June. These moves calmed investors, who bought his argument that the company was headed toward smoother seas. But now we know that Musk’s attempt to be an all-encompassing CEO, an executive involved with every aspect of his business, is causing serious personal and professional problems.

The sense that Musk may be losing it is most apparent in the public statements he has made over Twitter. Musk has spouted off about the free press, called a diver who helped rescue a trapped Thai soccer team a “pedo,” and, most dramatically, invited scrutiny from the Securities and Exchange Commission by tweeting that he had secured funding to take Tesla private, even though he had not. Musk told the Times that he does not regret the tweet about taking the company private, but it is likely to cause problems for him and the company, since many legal experts believe that he committed securities fraud. In all likelihood, he will simply have to pay a fine, but the damage done to his reputation may cost him more.

In the Times article, Musk also speaks about his dependence on Ambien. There is a strong implication that many of Musk’s bizarre late-night tweets stem from taking the prescription sleep aid and “recreational drugs”—and that Tesla’s board of directors is “aware,” if not concerned, about his drug use.

Musk’s drive to become a CEO with a hand in every aspect of each of his companies is simply not possible. Even a control freak like Steve Jobs, who Musk is often compared to, let others, notably Tim Cook, handle technical issues and logistics. Musk, in contrast, appears to aspire to a state where there are no distinctions between himself and Tesla.

This is most notable in Musk’s approach to short-sellers, whose trades appear to wound him personally. Tesla is among the most shorted companies in the history of Wall Street. Musk told the Times that he expects “at least a few months of extreme torture from the short-sellers, who are desperately pushing a narrative that will possibly result in Tesla’s destruction.” In Musk’s view, this is a kind of postmodern situation in which short-sellers are inventing an alternate reality for Tesla, then attempting to profit from it. In fact, short-sellers have lost billions betting against the company. Furthermore, these bets are highly rational given Tesla’s general shakiness. But in Musk’s view, critics of Tesla can only be haters.

Taken together, is there another motive to Musk taking the very risky move of opening up to the Times? Given his reputation for genius, there are always those who see his erratic outbursts and stunts as part of a larger game—Musk playing eight-dimensional chess. In the wake of the SEC reportedly handing down a subpoena over Musk’s taking-Tesla-private tweet, Musk could be floating a public relations strategy aimed at quieting regulators: the “ambien and stress” defense. In his telling, Musk’s devotion to the company is totalizing, costing him friendships, preventing him from even leaving its factories for days at a time.

But no amount of personal investment from Musk is going to suddenly start producing cars at a profitable clip. It doesn’t matter if Musk spends 40 hours working at Tesla or 120 or 160. Its problems are real and will require intensive, structural work. Musk’s “woe is me” interview keeps the focus on him and his struggles, rather than those of the company.

Either way, it’s clear that Musk is having problems. As the Times interview makes clear, he’s feeling sorry for himself and blaming his missteps on others. There are things Musk can control—he should sleep more and tweet less and find time to do things like attend the weddings of siblings. But so much of his ongoing spiral comes from him obsessing over things he can’t really control. Musk can’t single-handedly will Tesla to make more cars more efficiently, or for its autopilot to function properly. He is increasingly becoming a cautionary tale of the Great Man as CEO—he just doesn’t realize it, at least not yet.

The numbers alone are staggering: 1,000 victims, 300 priests. On Tuesday, to collective horror, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court released the results of its grand jury investigation into child sexual abuse in the state’s Catholic dioceses. The report spans all but one of the state’s dioceses and documents abuse that goes back decades. “There have been other reports about child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church,” the report begins. “But not on this scale. For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: It happened everywhere.”

Tale after tale of unimaginable exploitation and cruelty make up the grand jury report. One priest tried to tie altar boys up with rope. That same priest also belonged to a child porn ring with other priests. In a detail that reads like a fever dream, clergy gave victims large gold crucifix necklaces, which marked the children as prey to other members of the ring. One priest collected trophies of urine, pubic hair, and menstrual blood from female victims. Another impregnated a minor and urged her to get an abortion.

Throughout it all, the church stumbled over itself to protect its priests and its reputation. In 1996, the Pittsburgh diocese received a report that one priest had been repeatedly accused of “sexual impropriety”—he remained a priest until 2004. When dozens of parents complained that a different priest had inappropriately touched and ogled their naked sons at a Catholic school, the diocese removed him from the school, but issued him a letter of good standing in 2014 that denied that there had ever been any report of wrongdoing.

What happened in Pennsylvania is similar to what infamously occurred in the archdiocese of Boston, where victims were bribed into silence and accused priests were transferred to new parishes. What happened in Pennsylvania and Boston is similar again to what happened on the island of Guam, where there are 200 clergy sex abuse cases for a population of under 160,000 people and where the archbishop himself stood accused of rape. Other clergy scandals are unfolding in the cities of Buffalo and Rochester, New York; in Baltimore, Maryland; in Chicago, Illinois; in the countries of Ireland, Poland, Argentina, Australia, and Paraguay. The scandal is as universal as the church.

At this point, what could the church possibly do to cleanse itself in the eyes of its congregants and the world? And if the church cannot police itself, is there anything outside authorities can do to intervene?

The church’s secrecy is a repeating fact throughout the Pennsylvania grand jury’s narrative of predation. While dioceses did take some complaints seriously and removed priests from ministry, it’s clear that accused priests did not consistently face justice from their own church. Instead, dioceses shuffled priests from parish to parish. The report implicates some prelates: Cardinal Donald Wuerl, who served as the bishop of Pittsburgh before becoming archbishop of Washington, D.C., repeatedly allowed accused priests to remain in ministry, usually at the recommendation of the church’s own treatment centers for abusive priests.

How deep does the problem go? The sheer size of the Catholic Church means it’s difficult to know the extent of clerical abuse. In recent years, however, church officials have made efforts to provide a systematic approach to oversight and accountability. The Dallas charter, first created by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2002 and revised in 2005, 2011, and 2018, requires dioceses to publicize procedures for reporting abuse and to create review boards for investigating claims—boards that will include lay people as well as clergy. It further orders dioceses to “demonstrate a sincere commitment” to the “spiritual and emotional well-being” of victims and forbids dioceses from entering settlements that require confidentiality from victims unless it’s at a victim’s request.

The most important documents to emerge from the charter include two reports commissioned by the church in conjunction with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The first, released in 2003, examined the church’s abuse record from 1950 to 2002; the second, released in 2011, examined the “causes and context” of Catholic clergy abuse, and says the absence of “human formation” courses at Catholic seminaries contributed to abuse.

“Before, there was spiritual formation, intellectual formation, and pastoral formation,” explained Sr. Katarina Schuth, O.S.F., the endowed chair for the scientific study of religion at the Saint Paul Seminary and a contributor to the 2011 John Jay report. “Pope John Paul II required that there be a fourth area of formation, human formation, which included a good deal of more in-depth education about celibacy.” The idea was that previously the church had not properly prepared priests for a lifetime of celibacy. As a result of the human formation initiative, according to Schuth, abuse cases receded from their peak in the 1960s and 70s.

But the Pennsylvania scandal, combined with recent revelations that Cardinal Theodore McCarrick rose to the upper echelons of the church even though some officials knew he had sexually abused seminarians and altar boys, shows that there is a limit to the church’s willingness to take responsibility for the decades of suffering it has caused. When confronted with the realities of abuse, it covers it up, retreats to a defensive crouch, or attributes abuse to external, rather than internal or doctrinal, factors.

On Tuesday, the archdiocese of Washington, D.C., launched a short-lived website dedicated solely to the defense of Cardinal Wuerl. Some priests also offered up scapegoats. “Men who have suffered sexual abuse, in particular as a child, should not be admitted to priestly formation,” tweeted Fr. Kevin M. Cusick. “They need help of an intense kind and that would not be it. On the contrary, for some it has proven an insuperable temptation. Children should never be thus placed at risk.”

At the religious journal First Things, Fr. Dominic Legge, O.P., who teaches systematic theology at the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., blamed gay priests. “First, we need to investigate the past and have a transparent accounting of the failures. How were known networks of active homosexual priests (and bishops) allowed to continue?” he asked. Legge recommended screening out priests who have “a history of deep-seated homosexual attraction.”

Legge isn’t the first Catholic to pin clergy abuse on the presence of gay priests, or to link homosexuality with predatory behavior. The Vatican’s then-secretary of state, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, told the Chilean bishops’ conference in 2012 that “many psychologists and many psychiatrists” had told him “that there is a relationship between homosexuality and pedophilia.” In 2018, Chilean police raided the same bishops’ conference as part of an investigation into child sex abuse committed by members of the Marist Brothers.

The 2011 John Jay report rejected any causal link between homosexuality and child sex abuse, and so do other clergy. “It’s true that many of these cases are men abusing boys. But you can’t blame all gay priests,” Fr. James Martin, S.J. told me in an email. “It’s very close to saying homosexuality leads to pedophilia, which is the worst kind of homophobia. The reason you don’t see counterexamples of the many healthy celibate gay priests is that they’re afraid to come out—now, more than ever, in this environment of blaming and stereotyping.”

Martin also rejected the idea that clerical celibacy is the root problem. “I think a clerical culture of secrecy and privilege contributed more,” he wrote. “Most abuse happens in the context of families, but does anyone believe that heterosexuality or marriage causes abuse? Blaming it on celibacy is really missing the boat.”

But the church’s highest officials are still reluctant to relinquish that privilege and secrecy. In New York and Maryland, the church opposed bills that would have expanded the statute of limitations for child sex abuse cases, further restricting accountability for pedophilia and more. (The archdiocese of Baltimore did not return a voicemail requesting comment; the New York State Catholic Conference did not have a spokesman available for comment.) And it is worth remembering that the only reason we are having this discussion is that Pennsylvanian authorities stepped in. If the church truly intended to shed light on past and present abuse, it wouldn’t have taken a grand jury investigation to expose the abuses in Pennsylvania. For his part, Martin believes that if the statutes are expanded, secular institutions should be included in that expansion, an argument echoed by Fr. Thomas Reese, S.J. at The National Catholic Reporter.

Aside from expanding that measure in a way that includes secular institutions, there’s little secular authorities can do without running afoul of the First Amendment. The constitutional wall between church and state means that the state has an obligation to protect the church’s ability to conduct business in accordance with its doctrinal dictates—which means reform to doctrine, priestly oversight, education, and systems of accountability can only come from within. Victims of clergy abuse do not even have a universal right to sue the church for negligence that contributes to abuse; some state supreme courts have ruled against it on religious freedom grounds (others have permitted it).

In any case, it is already illegal to abuse children. Crimes committed by predatory priests aren’t just crimes against the Catholic faithful. They are crimes against all society, to which Catholics belong. Priestly crimes do not end at the doors of the church; they afflict neighborhoods and cities and states, too. The church then has an obligation to the public as well as to its own laity. And that obligation is to tell the truth, and to do so in the open, even it it harms church coffers.

It is possible for the church to fulfill its obligations without sacrificing its constitutional rights. In a July column for The New York Times, in response to the McCarrick scandal, Ross Douthat urged Pope Francis to convene an inquest, “a special prosecutor—you can even call it an inquisition if you want—into the very specific question of who knew what and when about the crimes of Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, and why exactly they were silent.”

Douthat’s call resembles an earlier thought experiment by Jennifer Haselberger, a whistleblower who resigned from the St. Paul-Minneapolis archdiocese over an abuse cover-up. Haselberger, a canon lawyer, suggested a truth and reconciliation committee, based on the post-apartheid South Africa model. Haselberger’s proposal would still be an internal investigation, but its results would presumably be public—and that is exactly why Haselberger has said her experiment will never take shape as a real effort. “If we had bishops all of a sudden admitting to knowledge and actions...in any kind of public forum, we’d never be able to prevent that from being used against them, which could lead to criminal prosecutions, civil liability, we just can’t control that,” she told the National Catholic Reporter in 2014.

On Thursday, two full days after the grand jury report broke, the Vatican released a six-sentence statement about the report’s findings. Lessons must be learned, said the Holy See; abuse is “morally reprehensible.” It urged accountability, but did not explain how it planned to achieve that goal. Meanwhile, Pope Francis’s current itinerary for an upcoming visit to Ireland lacks a visit with victims of clergy abuse. Victims and faithful Catholics alike must then hope and trust that the church’s current procedures are enough to prevent future outbreaks of abuse—that the Vatican takes the problem seriously, though its prelates and even the pope either contribute to the problem or respond tepidly to its moral and criminal outrages.

One of the most disturbing details of the Pennsylvania report did not describe the abuse of children. “Abuse complaints were kept locked up in a ‘secret archive.’ That is not our word, but theirs; the church’s Code of Canon Law specifically requires the diocese to maintain such an archive,” the report states. “Only the bishop can have the key.”

There is a joke that I have started hearing around New York City, in the (admittedly small) publishing circles I travel in: that if you hear a good tidbit of gossip, you can almost guarantee it will appear in subtly fictionalized form on the next season of Younger, a sitcom set in the book world. In one episode, rumors circulate that literary authors are choosing to boycott Achilles, a behemoth that resembles Amazon. In another, the Lean In phenomenon becomes Get Real, a philosophy dispensed in Dr. Phil–style sessions by an aggressive woman in a sheath dress. Later, Annabelle Bancroft (Jane Krakowski) serves as a Candace Bushnell–esque sex writer, whose books bear titles like Shedonism and Mantastic. No trend is spared: The show pounces on hygge, Marie Kondo, adult coloring books, Pod Save America, Reese Witherspoon’s book club, and even self-help tomes written by a dog.

Now in its fifth season, Younger airs on TV Land, an other-wise sleepy corner of the Viacom empire, best known for reruns of Gunsmoke and M*A*S*H. It is an unlikely home for a show that has gained a serious cult following since it debuted in 2015, especially within the industry it portrays. If there is one thing that creator Darren Star—the man behind a handful of other high-gloss hits, such as Melrose Place and Sex and the City—knows, it is a winning television formula: Take an insular, aspirational world (an exclusive Los Angeles housing complex or Manhattan before the financial crisis or the petri dish of New York publishing) and blow it up into a glittery cartoon-land where farce and reality are all mixed up. Sex and the City has long been lambasted for its inaccuracies and omissions, but it endures 20 years on because of all the details it got right: At the turn of the millennium, New York really was becoming more selfish, more consumerist, more focused on the ambitious individual.

Younger shares a large swath of DNA with Sex and the City (including its stylist—the series’ exaggerated outfits spring yet again from the mind of the eccentric costumer Patricia Field, who is not afraid to dress a woman in head-to-toe marabou and spangles), but it reflects a less glamorous world. In the years since Carrie Bradshaw paid her rent with a weekly column, the writing economy has suffered extreme shifts: It has gone digital, collapsed, briefly revived, collapsed again. Many of the female employees in Younger have to deal with workplace discrimination and the perils of ambition; they labor to keep their industry afloat, even as new technology scratches at the door (a multi-episode arc in which a tech scion attempts a hostile takeover of a publishing house centers this last anxiety).

Perhaps Star chose to make a comedy about book publishing because it initially looked luminous and cosmopolitan, but it has become a clever conduit through which to take on a wider range of issues. Publishing, at its heart, is about trying to capture and disseminate the zeitgeist; many of the conversations that the characters end up having on Younger are about how best to shepherd these new stories into the world and about the bumps they hit along the way. Although launched as a summer show with a fun, outlandish premise, for five seasons Younger has gone much further, offering a sharp critique of how culture gets made.

Let’s get that outlandish premise out of the way: Younger is a show about a 40-year-old woman who pretends to be, well, younger. When the show begins, Liza Miller (Sutton Foster) has recently separated from her husband, and her college-bound daughter is traveling abroad. She once worked at Random House but has been out of the publishing game for nearly two decades, having ditched her editorial goals and languished for years as a New Jersey stay-at-home mom. Embracing her newfound adult freedom, Liza relocates to Brooklyn. She moves into an airy Williamsburg loft—perhaps the least believable element of the show—with her best friend, a vampish lesbian artist named Maggie (Debi Mazar). Still pining for the book world, she starts applying for jobs but finds that, at her age and with her stunted experience, no corporate HR rep will even entertain her résumé, let alone give her any real power.

So she lies. Five seasons of sitcom antics begin when Liza removes from her CV any details that might suggest her age and scrubs all evidence of her earlier life from the internet. She claims to be 26, a stunt that only works because of Foster’s deceptively youthful visage (an entire cottage industry has sprung up around trying to replicate her anti-aging techniques). One big white lie and a forged driver’s license later, Liza lands a gig as an assistant at a tony publishing house called Empirical Press, which has been run by the same family for generations. Charles Brooks (Peter Hermann), the publisher who inherited the role from his father, is a dapper, suit-wearing executive with an old-school mentality; he likes Scotch, cherry-wood furnishings, and the collected works of John Updike. He runs Empirical alongside an elegant head of marketing named Diana Trout (Miriam Shor).

Diana serves as a mentor, a scold, and even a visionary—she can take a quiet novel like P is for Pigeon and convert it into a sleeper hit.Liza’s closest confidant at Empirical is a buoyant assistant editor named Kelsey (Hilary Duff). Despite being the sort of aggressively mainstream young person in New York who survives on Greek yogurt and SoulCycle, Kelsey has a slow-boiling ambitious streak, and Charles puts her in charge of her own imprint. She is (actually) 26, and she makes a strong case for a new line of books called Millennial Print, which would highlight the work of and address the issues that plague young people today. Whether or not this would work in the real world, Kelsey makes a convincing argument in the fictional universe. Books are changing, she insists. Young people are reading in new ways: They want covers they can Instagram, bite-size kernels of wisdom they can tweet out. The pitch flies, and Kelsey wrangles Liza into running the imprint as her partner.

Together they set off on a hunt for new authors and clash with some old ones. A major source of conflict is Empirical’s star author, Edward L.L. Moore (Richard Masur), a George R.R. Martin figure, who has written his own fantasy series featuring lithe women in fur bikinis. An unsavory air lingers around this character: In one episode, Liza is forced to dress up in scanty clothes to play Moore’s heroine “Princess Pam Pam” at the Times Square launch of a new installment of his Crown of Kings series, a role that makes her deeply uncomfort-able. Then, at the beginning of season 5, the #MeToo movement reveals that Moore has a history of badly mistreating women. (Here the show diverges from reality: Such charges have never been brought against Martin.) Charles cancels Moore’s next book, which leads Moore to blackmail Charles, showing him documents that prove Liza’s real age. This is a pickle, as Charles has slowly been falling in love with Liza, an inappropriate office relationship with its own murky ethical dimensions.

Liza may have lied about her age, but she did it in order to overcome a mountain of ageism and sexism. What’s most surprising about Younger is that through incredibly specific publishing jokes it has managed to make the viewer not only feel sympathetic toward a woman who has built her career on a lie but also root for her. The book world can be hypocritical, superficial, and obsessed with youth. But it is also thrilling, full of promise, and, as several of the projects mentioned on Younger indicate, still a hotbed of creativity and new ideas. We want Liza to be able to be a part of all that.

In the fifth season, I’ve come to realize that Younger’s most revelatory character may not be Liza or Kelsey, who keep getting trapped in deceitful webs of their own making. Instead, it is Diana. Though her role is really a composite of several jobs in publishing (she seems to combine marketing, publicity, packaging, and scouting in a single powerhouse), her character remains an accurate depiction of a certain type of industry grande dame. She serves as a mentor, a scold, and sometimes even a visionary—she can take a quiet novel like P is for Pigeon (a thinly veiled parody of Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk) and convert it into a sleeper hit. But she also represents a kind of throwback to an earlier, corporate-friendly feminism: She has had to fight her way into her position, and this has left her emotionally stiff.

Most of the young women on Younger are on an upward career trajectory and are skilled at coordinating their lines of attack in order to get ahead. For Diana, a lone wolf who already wins awards at galas, the show is about stumbling into vulnerability and beginning to trust other women, even those less experienced than her, to come up with some of the answers. This season, she befriends Lauren (Molly Bernard), a social-climbing, neurotic young publicist who calls Diana “diva” and urges her to embrace her own sexual power. When Diana learns that Enzo, a plumber she is dating, is a former porn star, she decides that she can either run away from the embarrassment or accept the fact that everyone comes with a backstory. Diana has always been the go-to problem solver at Empirical, armed with an old-school fierceness; much of her arc on the show is about learning to ask for support.

Perhaps this is the most poignant note the show has to offer about the publishing business: At one point, women had to go it alone if they wanted to get ahead. But this thinking will not push the industry forward forever. At the end of the fifth season, Kelsey acquires a business book called Claw that encourages women to be ruthless, to step on everyone else to get ahead. Diana clucks when she hears the pitch. She already knows that the idea is specious. But, she sighs, she can turn it into a best-seller.

Chrissy Houlahan has almost everything Democratic strategists look for in a candidate: A political newcomer, she served in the military and has experience in both the public and private sectors. But perhaps most importantly, this mother of two—affluent, white, and well educated—seems tailor-made to appeal to the suburban women Democratic strategists believe will decide the midterm elections.

Their focus on suburban mothers isn’t new. In 1996, a Washington Post article introduced the “soccer mom” to readers as “an overburdened middle income working mother who ferries her kids from soccer practice to scouts to school.” Journalists spent much of that election scouring suburban parks in search of soccer moms to interview, and both Bill Clinton and his opponent, Bob Dole, geared their campaigns toward the wishes of these voters. Clinton advocated for school uniforms, family leave, teen curfews, and the V-chip to block obscene programming on television—proposals designed to help suburban Americans who, he said, “play by the rules.” As his allies at the Democratic Leadership Council would write two years later, “Sprawl is where the voters are.”

When Clinton won 53 percent of suburban women and kept the White House, the soccer mom was established as a force in American politics, and she has remained one, to varying degrees, ever since. The language has changed over time: In 2003, after September 11, she was a “security mom,” and in 2008, during Sarah Palin’s vice presidential campaign, a “hockey mom.” But the promises Democratic presidential candidates made to her remained largely the same. In 2000, Al Gore promoted a “livability agenda,” promising to address traffic congestion and create more open space and public parks in affluent suburbia. Barack Obama took a similar approach in 2008. Swearing to transcend the red-blue divide and “invest in our middle class,” he won more of the suburban vote than John McCain and, with it, key battleground states like Virginia and Colorado. In 2016, Hillary Clinton paid her own homage, holding events with women in the suburbs of Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, where she discussed the cost of childcare and the need to respect women and girls. “We know that white suburban women are critical for both parties,” a senior Clinton campaign official told The Washington Post almost a month before Election Day. They were, the official said, “the lowest hanging fruit.”

/* ARTICLE 150452 */ #article-150452 .article-embed.pull-right { color: #be8d66 !important; text-align: center; } @media (min-width:767px) { #article-150452 .article-embed.pull-right { max-width: 230px; text-align: left; } } #article-150452 .marginalia { line-height: 1.4em; } #article-150452 .marginalia h3 { font-size: 1.1em; line-height: 1.4em; margin-top: 0; } #article-150452 .marginalia h2 { border-top: 6px solid #be8c65; margin: 0; padding-top: .6em; line-height: 1.4em; } #article-150452 .marginalia p { font-family: "Balto", sans-serif; line-height: 1.4em; margin: 0; font-size: 1em; } #article-150452 smaller { font-size: .7em; display: inline-block; line-height: 1.2em; }“What’s a Soccer Mom Anyway?”—The New York Times, October 1996

“Goodbye, Soccer Mom. Hello, Security Mom.” —Time, May 2003

“Just your average hockey mom.”—Sarah Palin at the Republican National Convention, September 2008

Two years later, Democratic strategists aren’t just trying to reach soccer moms. They’ve recruited candidates who are soccer moms: In New Jersey, 46-year-old Mikie Sherrill, a former Navy helicopter pilot and federal prosecutor who coaches her kids’ soccer and lacrosse teams in Montclair, a desirable New York City suburb, is running for Congress in the 11th District. And in Nevada, Democratic congressional candidate Susie Lee started a weekend sports league for low-income kids, which included soccer practice—something that features prominently on her campaign web site. Even Houlahan, who is running for Congress in Pennsylvania’s 6th District, in the Philadelphia suburbs, uses soccer mom rhetoric. “I really do think I’m being called off the sidelines in a really important time in our nation’s history,” Houlahan told Vice in January.

She’s a good pick for her district, which is overwhelmingly white. But elsewhere, the suburbs are changing. As cities began to gentrify in the 1970s, people moved to the suburbs in search of cheaper housing. Suburbs now have a higher rate of poverty than many urban areas do. More than 60 percent of their adult residents do not have college degrees; 35 percent, according to a 2010 Brookings Institute report, are minorities. Even soccer itself—the preferred extracurricular activity of white suburban children in the 1990s—has undergone a change. Parents now routinely shell out thousands of dollars annually for their children to participate in leagues and tournaments, excluding the growing number of low-income immigrant and refugee children living in the suburbs.

As the suburbs change, Democrats will need fewer candidates like Houlahan and more who can speak to the diverse and financially strapped voters who represent tomorrow’s sprawl. These future voters will likely be more concerned with economic equality than economic growth, criminal justice reform more than national security—and they will see “livability” in a higher minimum wage and debt relief, not in easing traffic flows and creating more open space.

In this, Stacey Abrams, the African American Democratic candidate for governor in Georgia, may be a better model. Her suburban strategy is focused on the large African American population that has been settling in the suburbs outside Atlanta over the last 20 years. Her platform is unapologetically left-leaning: pro-choice, pro–gun control, and pro–public school. Whatever the outcome in November, her win in the primary is a clear reminder that Democrats can’t rely on the strategies and definitions of the past. They have to see the soccer mom for who she is now—and go get her.

If you designed a job to embody a kind of old-school masculinity, you couldn’t do much better than orca capture, which combines elements of hunting, fishing, rodeo, and unfettered capitalism. Chasing, corralling and trapping these giant predators of the sea requires a certain toughness: In the course of a whale hunter’s career, he might harpoon a juvenile and tow it by boat, or separate a crying baby from its family, or use the cries of the baby to lure the rest of the family into a trap. But the old salts in this business end up reflective and teary, because upon closer contact, it turns out their prey are smart and social animals who behave gently and tenderly toward each other and the humans they bond with.

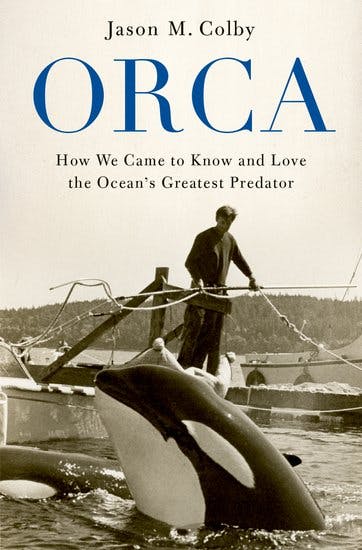

ORCA: HOW WE CAME TO KNOW AND LOVE THE OCEAN’S GREATEST PREDATOR by Jason M. ColbyOxford University Press, 408 pp., $29.95

ORCA: HOW WE CAME TO KNOW AND LOVE THE OCEAN’S GREATEST PREDATOR by Jason M. ColbyOxford University Press, 408 pp., $29.95We already know this about orcas, of course. And we know it largely because of the orca display industry, which showed us decades of these giant dolphins interacting with humans, doing tricks, exhibiting levels of intelligence and emotion close to our own. Boomer children met Shamu, SeaWorld’s first performing orca, in the mid 1960s; millennials had the 1993 film Free Willy, which spawned three sequels, and made its killer-whale cast member, Keiko, a star. A campaign sprung up around the idea of giving Keiko, who had spent two decades in a small tank in a Mexican amusement park, the same freedom as the fictional Willy, and in 2002 Keiko was released in Iceland.

A turning point for the industry came in 2013 with the documentary Blackfish, which told the story of Tilikum, an orca that killed a trainer at SeaWorld in Florida. It offered a grim view of Tilikum’s life—spent isolated from others of his species, without the social bonds of a wild pod, confined to a pen where he swam in tiny circles for so long that his dorsal fin flopped to one side—and of the orca-display industry in general. We had learned from captive orcas that the species was incredibly smart and social; Blackfish argued that these very qualities made them suffer in captivity. After the film’s release, public opinion turned against marine parks, particularly SeaWorld, which reported an 84 percent drop in profits in 2015.

Jason M. Colby chronicles this rise and fall in his book, Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator, beginning with a time when killer whales were still viewed as monsters and pests. Much of the action centers on the 1960s and 1970s, when the systems that led to the Tilikum tragedy were being put into place. It is a story not just of the orca business, but also of the evolution of Americans’ relationship to the oceans and marine life—the growth of marine parks parallels the shift from an extractive approach to the ocean, as mainly a source of fish, to a recreational one. It intersects, too, with the birth of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s and 70s, a time when Greenpeace was campaigning to “Save the Whales” and one of its leaders, Paul Spong—who, makes cameos in Colby’s book as a young researcher—would play his flute to the captive whales.

For a generation that grew up on Shamu or Free Willy, anecdotes that Colby shares of orca hunters in “the Old Northwest” are shocking. The orcas then were seen as competition; hunters and fisherman would shoot up pods of orcas because they were eating up the salmon or seals that the fishermen wanted for themselves. Some of these stories date from the late 1800s and 1910s; but as late as the early 1960s, orcas had a reputation as a dangerous nuisance. “They ought to bomb all them dumb whale out of here,” says one Washington fisherman in 1962, “use them for target practice.”

The book’s main character, Ted Griffin, grows up in this “rough and tumble” environment. Colby paints the young Griffin as a “Tom Sawyer of Puget Sound,” who loved the sea and animals. He was, as a teenager in the late 1940s, one of the first scuba divers in the Salish Sea, after ordering an early iteration of Jacques Cousteau’s new contraption, the Aqua Lung. Around this time, the economy in the Pacific Northwest was changing, drawing workers into cities and office jobs, away from extractive industries, and, as Colby puts it, “the shared world of fishermen and orcas was changing.”

In the new Northwest people like Griffin with his diving gear started looking to the ocean for recreation and not just resources. In 1961, he had a close encounter with a pod of orcas. He saw them “nosing around in a kelp bed” near his home and rowed out to take a look. A large male orca dove under his boat and rolled onto his back, looking up at him. As the pair stared at each other, Griffin underwent a transformative moment: “Mesmerized,” he “imagined swimming alongside the graceful creature, breaking down barriers between species.”

The orca’s desire to communicate moved Griffin to tears, even as he continued working on its cage.Griffin pursued his dream of connecting with killer whales, but it wasn’t all inter-species eye contact. The first orca Griffin procured, Namu, was caught accidentally by some fishermen, when a snagged fishing net trapped a pair of orcas between a reef and a rocky outcropping. There was a passageway out of the net, and Namu, the bigger orca, tried to nudge the younger one (likely his sibling) out through the hole. When this failed, he swam in and out himself, demonstrating how to get out. But the baby wouldn’t follow, and rather than leave him alone there, Namu stayed. It took Griffin a few days to get to the whales; during that time, other members of the pod congregated outside the net and called to the ones trapped inside. The younger orca did eventually escape, but it was too late for Namu. Griffin bought him for $8000, delivered to the fishermen in small bills that he’d borrowed from a collection of friends and neighbors.

From that moment on, Griffin’s career—and his relationship with the whales he loves—was full of contradictions, which often reflected the tensions at the heart of the entire display industry. Griffin was driven by his desire to connect with the animals. As he constructed Namu’s harbor pen, swimming with the animal in a wetsuit, Namu chirped at him, and mimicked the sounds that Griffin made into his diving mask. The orca’s desire to communicate moved Griffin to tears, even as he continued working on its cage.

“I wanted Namu to be free,” Griffin told Colby, years later, “but couldn’t part with him.” Griffin and Namu did bond, and Namu earned a reputation as a “gentle giant”; Griffin would swim with him and ride on his back and never came to harm. “By all accounts, Namu was a sweet soul,” Colby writes, noting that orcas have unique personalities and that “Namu clearly came to relish close contact with his owner.” They are also social animals, and its perhaps unsurprising (now) that an orca separated from its podmates and kept in isolation would seek out other bonds where it could.

Griffin’s career progressed in parallel with the industry itself. It was Griffin who caught Shamu, the first healthy orca ever captured intentionally. (He was a major player in the orca-capture business but, it should be noted, certainly not the only one.) Shamu (short for “She-Namu”) was supposed to be Namu’s “bride,” but when Griffin introduced her, she seemed to hate both Namu and Griffin, and to especially hate the bond between them. She would knock Griffin off of Namu when he rode the whale, and was aggressive toward them both. Maybe she was holding a grudge; she was captured as a juvenile and her mother died in front of her in the course of the capture. In 1965 Griffin sold her to SeaWorld, where she became a celebrity. Though the original Shamu died in 1971, SeaWorld continued to use “Shamu” as a stage name for the orcas in its theatrical shows for decades.

As the years pass, there is so much violence against orcas that the incidents start to blend together. A captive orca is dropped on its head during a transfer and soon dies. Another crashes through the glass of a window in its display tank. Many are harpooned; one is harpooned on a line that’s connected to a helicopter, with the idea that the helicopter would eventually tow it to shallow water for capture; instead the animal dives deep, swimming so strongly it pulls the helicopter down with it.

And what accumulates, too, is a new way of seeing and thinking about these animals. People learn that they are clever, and that they take care of each other. Time and again, they work together to hunt, or to try to escape humans; they hang around one another when one is captured but not removed from the water; they form bonds with one another and with humans. During one capture, when several orcas are corralled in a harbor, a thousand people show up to watch—“I was actually quite sad about the whole thing,” one of the captors recalls. “The whales were crying when you got one up on the dock and the other ones were crying in the water.” As the backlash against the industry rises, the irony is clear: The captivity and display industry made people love orcas, and then hate the captivity and display industry.

This is the central thrust of Colby’s book, and he returns to the point throughout, wondering how history should remember Griffin and his colleagues. Colby’s father was involved in a few captures, and later talks about them regretfully. How should readers think of him? It is an interesting question, but ultimately not as knotty a conundrum as the book makes it out to be—norms change, the culture changes, hopefully toward what’s more compassionate and humane. Plenty of behaviors that are now reviled were once not just legal but perfectly ethically mainstream. We can see such changes, know them to be just, and also understand that people used to operate with values, perhaps with different knowledge. With any luck, in half a century, some of our own activities will also be deemed too cruel.

He dove into libertarian politics, angry at the shift in environmental norms that suddenly made him into a bad guy.More interesting, to me, than the judgment of history, are the moral compasses of the crying men themselves, who knew—well before Greenpeace protestors and Blackfish and the Marine Mammal Protection Act—that the animals they were hurting were sentient and sensitive; that they were doing something wrong. Griffin talks throughout the book about a shift he underwent: from a boy who loved whales to a man who was in the whale business. As save-the-whales rhetoric rose up around him, he grew bad tempered. He dove into libertarian politics, angry at the shift in environmental norms that suddenly made him into a bad guy. Colby writes that when Griffin had started out, “the live capture of a killer whale seemed the antithesis of commercial whaling; now many viewed them as one and the same.”

Griffin later wrote that the regulations on whale-capture represented “the loss of one of my highest values, my freedom … the freedom to live and enjoy life to the fullest.” It could be, if pointed another direction, the exact language of an anti-SeaWorld activist. The story of the sad sea cowboys is one of shifting mores, sure. But it’s also a story of the intellectual hoops that we humans will jump through, like well-trained marine mammals, in order to justify the harm done in the course of making a living, or just doing whatever we want.

In September of 2009, Alan Grayson—a freshman Democrat from Central Florida—stood in the well of the House, flanked by an easel, and told Americans that “if you get sick … the Republican health care plan is this: Die quickly.” The brief performance propelled him into the media stratosphere. Soon, he was a regular on the Capitol Hill talk shows, MSNBC in particular, denouncing Dick Cheney as a vampire, a lobbyist as “a K Street whore,” and, later, the Tea Party movement as a modern incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. “If the hood fits, wear it,” Grayson repeated to those who pushed back. The more his targets railed against him, the more his base cheered—and sent him contributions. In the day after his “die quickly” speech, he raised $114,108.

Almost a decade later, Grayson has largely disappeared from the Washington spotlight. Two years ago, he gave up the House seat he’d occupied off and on since 2009 to run for Senate, vying for the seat that Marco Rubio had said he was giving up. Grayson didn’t even get the Democratic nomination. Thanks largely to the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee, Patrick Murphy, a centrist congressman from South Florida, who crushed Grayson in that August’s Democratic primary (and went on to lose in November). Now, Grayson has launched a bid to win his old seat back from his successor in the House, Congressman Darren Soto, a moderate Democrat. And while he may not win the August 28 primary, the race—perhaps the last act in his tumultuous political career—says a lot about how much the Democrats have evolved in the decade since he first entered politics.

In 2009, Grayson occupied a unique place within the party, both on policy and in politics: He was on its far left flank, pushing the Democrats in that direction on key policies, the Affordable Care Act among them. Today, however, many Democratic voices are articulating and advocating an unabashedly liberal agenda, one even further to the left than what Grayson advocated 10 years ago. Moreover, back then, he filled a prominent, even needed, role as a designated Democratic bomb-thrower, the only person willing to push back against tepid, liberal pragmatism and criticize the GOP. But now, with an unpopular president in the White House, many Democrats, from newcomer Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to veterans like Maxine Waters, Nancy Pelosi, and Adam Schiff, have taken that role upon themselves. They’ve abandoned “civility” for the more aggressive style Grayson pioneered years ago. If he has left a mark on the party, the party, it seems, has only passed him by.

To say Grayson is not a favorite of the Beltway Democratic establishment would be a titanic understatement. In his pre-candidate days, when he was a successful trial lawyer—winning headlines for suing corporate profiteers during the Iraq War on behalf of whistleblowers—Grayson was a courted party donor. That changed when he arrived in Congress in 2009.

Almost from the start, he alienated colleagues, staff, and lobbyists of both parties—even erstwhile allies. Critics describe Grayson as a man of towering ego and arrogance, which he dismisses as justified self-assurance. When talking to journalists, always off the record, those who knew him then use various pejorative metaphors for this hostility: thorn in the side, stone in the shoe or—the consensus pick—simply a self-righteous pain in the ass.

At the Democratic National Convention in 2016, just as his Senate campaign appeared to be gaining traction, his estranged wife leaked police records from Northern Virginia and Florida, accusing him of domestic violence, to Politico. Questioned about the charges by a Politico reporter, a sweaty, clearly unhinged Grayson got into a shoving match with him and threatened to have him arrested by Capitol Police. Several liberal groups that had endorsed him immediately rescinded their backing. And even though the reports were never authenticated—and in fact, Lolita Grayson later admitted to having fabricated them—their mere existence two years later, in the #MeToo era, could be tough to overcome.

There’s another reason Grayson seems so out of touch with his party today. In his last two terms, from 2013 to 2017, he pulled off a stunning transformation into an effective legislator, developing a productive relationship with the Republican House majority. By his count, he passed or sponsored more than 100 bills, resolutions and amendments, many of which were enacted into law in some form. These included measures that shielded homeowners from predatory mortgage foreclosures and provided free tax preparation assistance for seniors. Grayson’s work led Time magazine to list him among the five most productive bill writers in both houses. Slate magazine put it this way in a headline: “The Congressman Formerly Known as Crazy: Why Alan Grayson is now the most effective member of the House.”

Today, with Democratic activists now calling on their representatives in Congress to “resist” everything the GOP does, Grayson’s history of cooperating with Republicans puts him in awkward, contradictory territory—even more so now, as he hits the campaign trail trying to highlight just how leftist he actually was all along.

There’s no question that Grayson stands to Soto’s left. Soto has accepted money from the sugar industry, utility PACs, and even Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s family. As a state legislator, he once voted to prosecute abortion as murder, and backed Stand Your Ground legislation drafted by the gun lobby, leading to an NRA endorsement. Soto has since tried to walk back these positions, especially after the Orlando Pulse nightclub and Parkland shootings. But Grayson has still been using those stances to draw out some strong contrasts, campaigning on gun control, reproductive choice, public schools, and, to a lesser degree, the impeachment of President Donald Trump. He is an outspoken and consistent proponent of all four. In a July 4 email blast to his supporters, he wrote, “I look forward to impeaching him, convicting him, and removing him from office.” Around the same time, the first of several billboards went up in the district—seen by more than 50,000 drivers daily—urging Americans to “Dump Trump” by voting for Grayson.

These aren’t unusual positions for a Democrat running in a contested primary. But to hear Grayson talk, you might think he was the second coming of Ocasio-Cortez, a political newcomer running against some Democratic Party machine man.

When I had lunch with Grayson at a restaurant near his home in the affluent Dr. Phillips area of Orlando last month, he was leaning into the idea that his race was another chapter in the tussle between the Democratic Party’s center and left. If he wins, he told me, “the party will have to come to grips with the fact that the leading champion in the country for increased wages, Social Security and Medicare knocked off an incumbent Democrat.”

Central Florida is not the Bronx, and, unlike Ocasio-Cortez, Grayson is no socialist.These parallels can be overstated. It’s true that Grayson has received an endorsement from a local group affiliated with Our Revolution. But Central Florida is not the Bronx, and, unlike Ocasio-Cortez, Grayson is no socialist. He has made expanded health care, “Medicare You Can Buy,” a centerpiece of his campaign, but that hardly seems radical in a district with a lot of seniors. To this, he proposes adding his own supplementary legislation, “Seniors Have Eyes, Ears and Teeth,” which would broaden Medicare coverage—as well as his own, across-the-board raise, called “Seniors Deserve a Raise.”

“Grayson is more progressive [than Soto], but I don’t think this primary is going to be determined by who is the most progressive on a set of issues,” says Rollins College political scientist Donald Davison. Lots of Democrats are touting such platforms now; Grayson isn’t the only one. Besides, there are more important, structural obstacles he would have to overcome to win the district.

Grayson was defeated in the 2010 Tea Party wave, but returned to office two years later in a redrawn 9th congressional district, designed to make it more favorable for a Hispanic candidate. Today, it stretches from Eastern Orlando into the working class suburbs to the South. Across the district, Hispanics, mostly from Puerto Rico, now account for 41 percent of the voting age population. Two years ago, they elected Soto—whose father was born in Puerto Rico, a fact he never fails to mention in stump appearances and in his campaign advertising—by a resounding margin. That year, he won the general election with 57.5 percent of the vote, becoming Florida’s first member of Congress of Puerto Rican descent.

Grayson has done everything he can to portray Soto as a “bootlicking lackey of the NRA,” a “professional poseur,” and “pustule on the hindquarters of American politics,” which, when asked, he says he intends to lance. Soto’s policies are “about as good as conservatives can hope for from his liberal democratic district,” according to the Sunshine State News. But with the district composed the way it is, that hasn’t really mattered. As the incumbent, Soto has most of the local, progressive endorsements that once went to Grayson. And, given the support he enjoys from the Beltway elite, observers believe he is a strong favorite to win the primary. The outcome may depend on which candidate has the more effective turnout operation.

But there is, Davison told me, a larger question at stake in this race: “What is the Democratic Party today? What is its ideology?” He believes that it’s “much more a collection of distinct identity groups, and less a party of ideology … better characterized as a party of policy pragmatists, one that is a much more culturally, racially ethnically diverse coalition of groups and their interests around the country.”

Many Democrats have pushed back on such thinking since the 2016 election, arguing that identity politics isn’t enough to bring the party back to power at the national level. But in a place like Central Florida, that may not be the case. There, it’s Darren Soto—this bland, soft-spoken, inoffensive, malleable centrist—not Alan Grayson, who appears to have the best shot at winning the Democratic nomination.

And if Grayson loses? Would this be the end for him? Maybe not, said Jim Clark, a political historian at the University of Central Florida. “I think he could become a perennial candidate.… It doesn’t matter whether he wins or not. I would not be surprised to see him jump into the 2020 presidential race!”

No comments :

Post a Comment