This spring, Google quietly removed its longtime unofficial motto, “Don’t be evil,” from its employee code of conduct. The motto was largely an exercise in branding rather than an ideological statement—over its three decades in existence the company has dealt with evil-ish issues ranging from tax avoidance to search engine manipulation. Still, the shift was significant, suggesting the company might be becoming more hard-nosed as it faces pressure to expand.

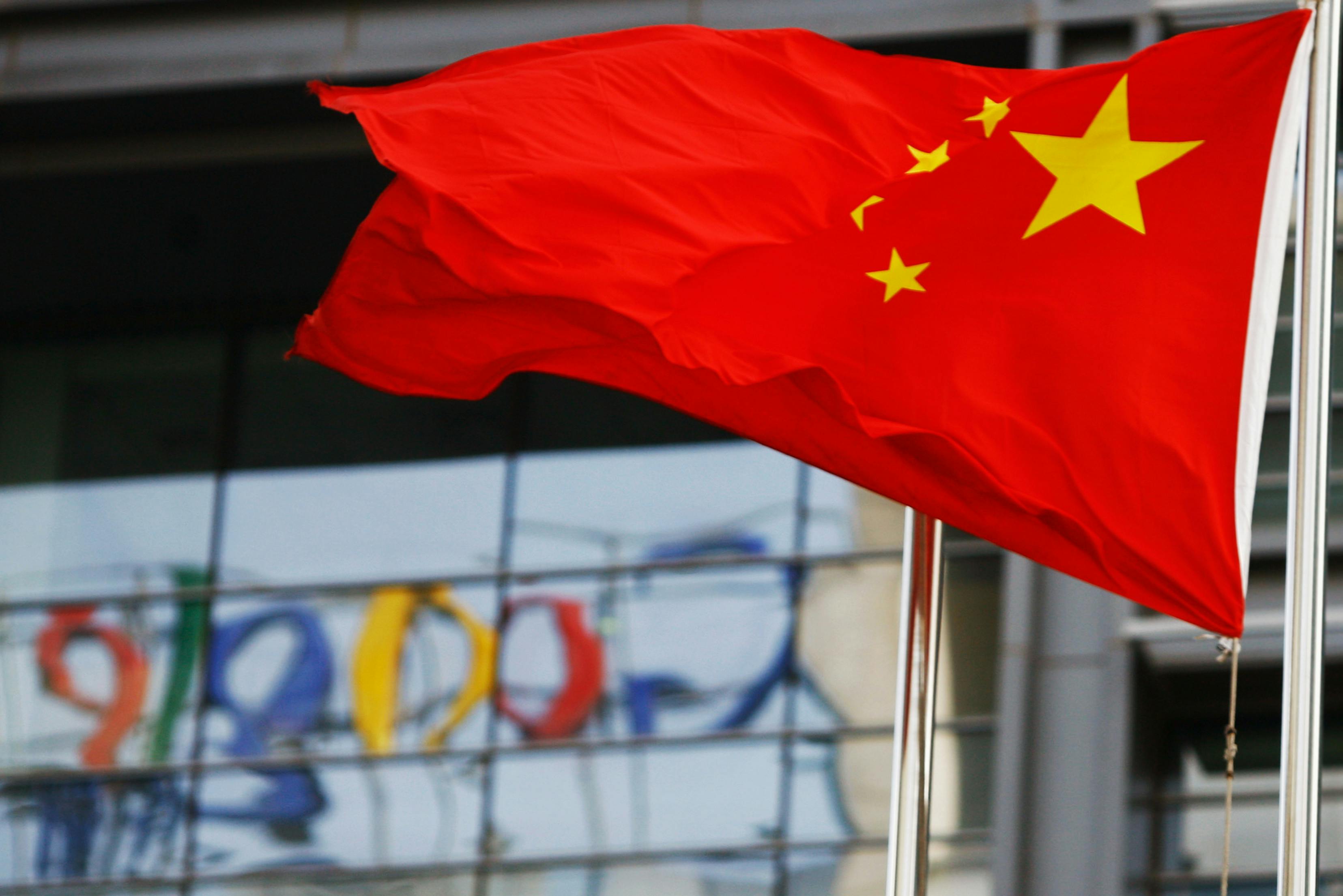

Google’s attitude toward censorship is a case in point. In 2010, Google effectively pulled out of China over censorship concerns, following a fight with Communist Party authorities over requests to filter its search results and the hacking of Chinese activists’ Gmail accounts. But now, Google is edging toward China again. Last week, The Intercept reported that a Google team is working on search apps that would comply with the country’s strict censorship regulations. That work is part of a slow shift toward China that began in 2016 when CEO Sindhar Pichai told investors, “I care about servicing users globally in every corner. Google is for everyone. We want to be in China serving Chinese users.”

The decision to re-engage with China says much about both Google and the state of Big Tech. In 2010, the Chinese market could be sacrificed to principle. But in 2018, Facebook is doing business with China (with all of the censorship that implies) and there is heightened competition from Chinese rivals like Baidu. Google may simply have decided that, when it comes to China, it is now or never.

Google’s relationship with the Chinese government, which explicitly favors homegrown companies like Baidu and has no intention of dismantling its “Great Firewall” censorship program, has always been complicated. Back in 2006, The New York Times’s Clive Thompson described the unsavory options facing the company:

If Google remained aloof and continued to run its Chinese site from foreign soil, it would face slowdowns from the firewall and the threat of more arbitrary blockades—and eventually, the loss of market share to Baidu and other Chinese search engines. If it opened up a Chinese office and moved its servers onto Chinese territory, it would no longer have to fight to get past the firewall, and its service would speed up. But then Google would be subject to China’s self-censorship laws.

Neither of these were particularly good options, especially for a company that prides itself on being liberal and open-minded. In 2006, Google ultimately launched a censored version of its search engine, with its leaders arguing that the overall result—i.e. Chinese citizens gaining access to a larger scope of information—was worth a little bit of censorship. There were difficulties from the outset, including congressional hearings in which the company was compared to the Nazi Party and forced to defend its decision to block search results for persecuted groups and its partnership with the Chinese Communist Party. But Google continued to operate in China until 2010, when government operatives used phishing attacks to target the Gmail accounts of dissidents, human rights activists, and rivals.

The biggest proponent of the decision to pull out of China was co-founder Sergey Brin. Born to a Jewish family in the Soviet Union, Brin has been outspoken about censorship and authoritarianism, before and after the company’s foray in China. Months after Google pulled out, he told Der Spiegel, “Having come from a totalitarian country, the Soviet Union, and having seen the hardships that my family endured—both while there and trying to leave—I certainly am particularly sensitive to the stifling of individual liberties.” But three years ago, Brin took on a new role as president of Google’s parent company Alphabet and his “influence at Google has been minimal,” according to Quartz. Pinchai, his replacement at Google, has not made free speech a signature issue, while he has made re-engaging with China a priority.

As reported by The Intercept, the thaw between the two sides has “accelerated” in 2018. The plan is to ultimately “launch a censored version of its search engine in China that will blacklist websites and search terms about human rights, democracy, religion, and peaceful protest.” This would allow the company to operate with minimal state intervention. According to documents viewed by The Intercept, the search engine will “automatically block” websites censored by China’s Great Firewall and will “blacklist sensitive queries.”

There are a number of risks in returning to China. The biggest is that, while Google may have hoped in 2010 that it would be able to return to a friendlier and less repressive China, the reverse is true: Over the last eight years, online censorship has increased. So Google risks becoming a political football once again. With Democrats and Republicans circling around Big Tech, building a censored search engine for a repressive regime with a strained relationship with the United States (and President Trump in particular) makes Google vulnerable to any number of political headaches.

Furthermore, Google’s policy toward censorship, along with its larger political attitudes, have been a recruiting boon. Some employees have criticized its decision to collaborate with Chinese authorities.

But growth is still the top priority for Big Tech companies. Earlier this month, Facebook lost over $120 billion in market value in minutes after it revealed growth numbers that were lower than investors and analysts had hoped—even though they were still substantial. By locking itself out of a market that contains hundreds of millions of potential users, Google has not only set itself back, but it has ceded ground to American and Chinese competitors. Eight years ago, Facebook had 500 million users; today it has 1.3 billion (2.5 billion when you count its other applications, including WhatsApp and Instagram). Tech is significantly more global than it was eight years ago and that means, as Pinchai surely realizes, operating everywhere—even in disagreeable places.

Google has liked to pretend that it’s not as rapacious as its competitors—that it’s a friendly giant. That it has the best interests of its uses and its communities in mind when it rolls out new products or enters new markets. In 2006, Brin could look at China and tell The New York Times that his decision to enter the market “wasn’t as much a business decision as a decision about getting people information. And we decided in the end that we should make this compromise.” In 2018, Google can’t make the same kind of claim. It is simply a big company that will do whatever it takes to get a little bigger.

Sanctioning another NATO ally is a remarkable move. As such, the Trump administration’s sanctions on Turkey’s justice and interior ministers last week, over the detention of American pastor Andrew Brunson, increased fears about the unraveling of a formerly strong alliance. Meetings between senior U.S. and Turkish officials in Washington on Wednesday failed to resolve the matter. U.S.–Turkish relations appear broken, with little prospects of repair—a new geopolitical reality.

Once upon a time, Turkey and the United States enjoyed a close partnership. Even when various issues, such as a divided Cyprus, caused frustration from time to time, the United States relied on Ankara and, particularly, Incirlik, a military base in southern Turkey. The U.S. helped to construct Incirlik in 1955, which served as a key airbase in the region during the Cold War and after, particularly during the first Gulf War in 1991. Turkey depended on U.S. aid.

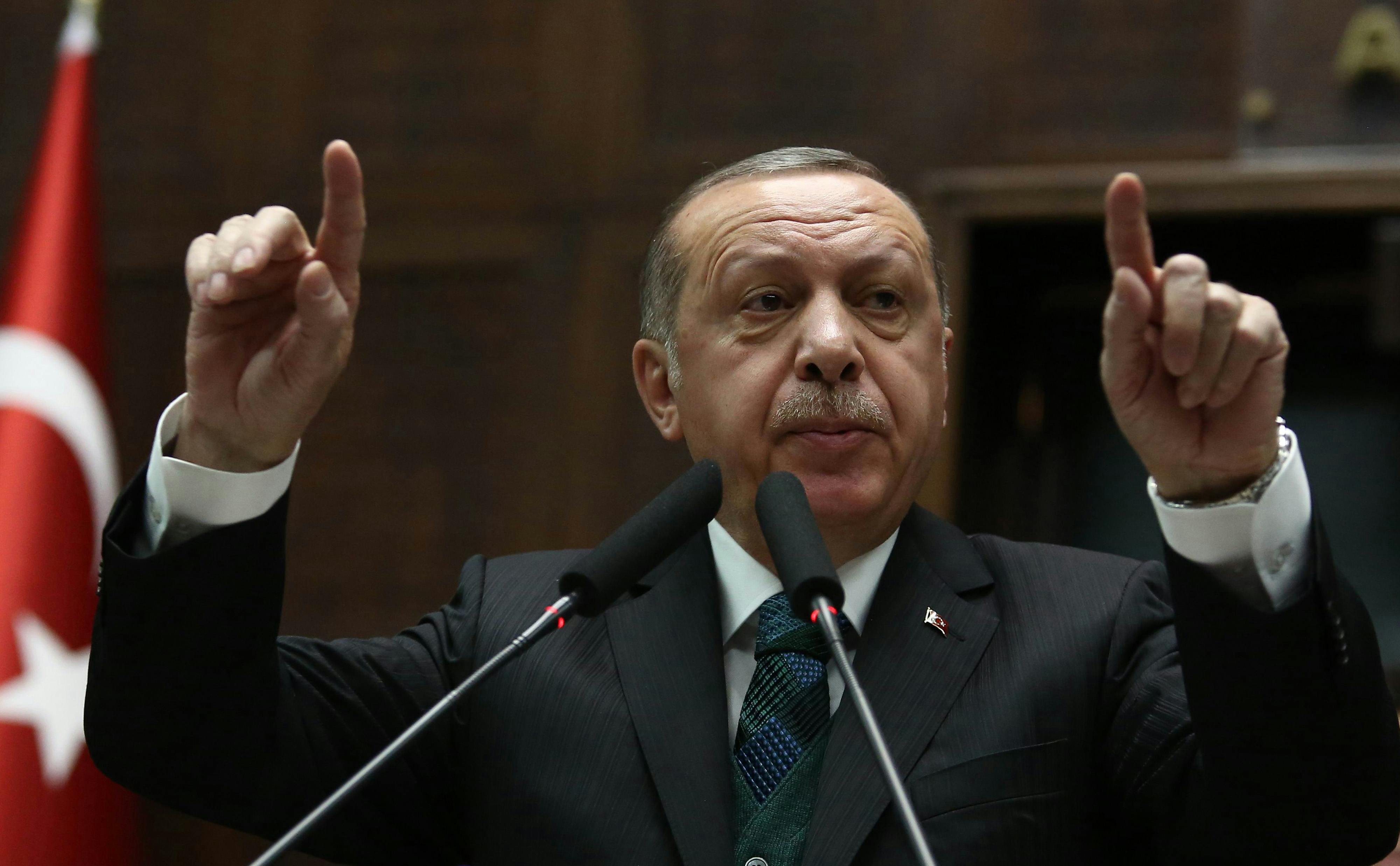

The rift between Turkey and the United States started in 2003, after George W. Bush invaded Iraq, which sits on Turkey’s southeastern border. The ensuing chaos and war affected the entire region, Turkey included. Relations improved temporarily when Barack Obama took office in 2008. The U.S. president landed in Ankara on his second international trip, making Turkey his first destination in the Middle East. Obama initially embraced then Prime Minister (now president) Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his government as a “model” for other Arab countries undergoing protests in 2011. But that relationship deteriorated as the Syrian civil war on Turkey’s border (and associated refugee crisis) worsened, while Erdogan faced nationwide government protests and corruption allegations.

Ankara’s ties to Washington have further eroded due to longstanding tension over a Turkish cleric living in exile in Pennsylvania—Fetullah Gulen. Once close collaborators, Gulen and Erodgan started to drift apart in 2010, after differences on how to deal with Israel following the attack on a Turkish flotilla. The relationship quickly turned nasty, with Erdogan accusing Gulen and his followers of releasing tapes that exposed corrupt practices in 2013. The Erdogan government held Gulen and his followers responsible for engineering an attempted coup in July 2016, and has demanded that the United States hand Gulen over.

Security is another issue. The United States has gravitated to the Syrian Kurds, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), in the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) in Syria and Iraq. The YPG has long fought ISIS—and has, in certain instances, succeeded. Unfortunately, Turkey does not look kindly on the YPG or the Kurds in general. The Kurds are Turkey’s largest minority and have long had tensions with the Turkish state over rights, which erupted in a war in southeast Turkey in the 1980s. Ankara fears that the Kurds will form an autonomous region along the Turkish border and catalyze Turkey’s Kurds to breakaway territory from Turkey. Earlier this year, Turkey attacked YPG forces in Syria and actually occupied the Syrian city of Afrin.

Ankara seemed originally to believe that President Trump, who owns properties in Turkey, would represent a reset in U.S.–Turkish relations. Indeed, in Brussels last month Trump remarked that he liked Erdogan and gave him a fist bump. That bromance was short.

Enter Brunson. In 2016, following a failed coup, Erdogan’s government began a large-scale crackdown on dissent. In the aftermath, Brunson was one of many arrested and accused of espionage and terrorism—of being in league with the Muslim Gulenists.

The current U.S.–Turkish feud feeds political narratives in both countries. Backing Brunson plays to the American president’s base—all the more conspicuously so given that NASA scientist Serkan Golge, a dual Turkish–U.S. citizen, is also being held in Turkey, serving out a seven-and-a-half-year sentence for charges similar to those being brought against Brunson. Golge is Muslim, unlike Brunson, whom Trump has called “a great Christian” and “innocent man of faith.” The Trump administration has said nothing about Golge’s detention.

The resistance to letting the pastor go plays similarly for Erdogan: Turkey’s economy has been declining. Inflation is up, and the central bank predicts a rise in food prices. These sanctions are perfect diversions and props for Erdogan to use to show how “outside” forces are plotting to ruin Turkey.

The fundamental reality is that Turkey is not as vulnerable to American actions as it once was.But ultimately, the current conflict reflects a larger shift in orientation. With President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s troubling consolidation of power in the past year, the spat over Brunson is likely only the beginning of a series of conflicts, in which the United States will have little leverage or bargaining power. Turkey’s economy is in bad shape, and the sanctions since last week have caused the Turkish lira to fall still further; but the fundamental reality is that Turkey is not as vulnerable to American actions as it once was. The European Union is Turkey’s main trading partner, with $84.7 billion in exports. Trade between the United States and Turkey, by comparison, amounts to only $9 billion. Foreign investors in Turkey also tend to be European, not American. U.S. foreign direct investment inflows are exceeded also by the Gulf countries.

As Trump alienates Europe, Turkey has used the opportunity to renew relations with its neighbors. The abandonment of the Iran nuclear deal is certainly a unifying point between Brussels and Ankara. Both capitals are eager to keep the Iran nuclear deal—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—alive, with Iranian oil accounting for nearly half of all Turkish imports in the first half of 2018. At Angela Merkel’s invitation, Erdogan will pay a state visit to Germany in September. Meanwhile, Erdogan is organizing a summit with France, Germany, and Russia to discuss Syria. He has also restored relations with The Netherlands, which had gone off the rails last year.

It is unlikely that the United States and Turkey will resolve their differences anytime soon. But given Turkey’s geostrategic location—in the backyard of Russia, and bordering Iraq, Iran, and Syria—the United States has an interest in maintaining the relationship. Turkey, meanwhile, does not need to add to its economic woes. The hope, at this point, is that as both Erdogan and Trump play to their bases, they’ll refrain from actions that would be hard to walk back from without embarrassment to either leader’s large ego. Despite the shifts of recent decades, the United States and Turkey still need each other. And the temporary political benefits domestically probably don’t outweigh that.

Six years ago, Congress passed the STOCK Act, which for the first time made members of Congress liable for insider trading, just like any other investor. On Wednesday, the Justice Department issued the very first indictment under that law when it arrested Representative Chris Collins, Trump’s earliest supporter in Congress, and accused him of sharing inside information about an Australian pharmaceutical company with his son and other investors.

Last year, Collins allegedly learned, before the public did, about the failure of a clinical trial for a multiple sclerosis drug by Innate Immunotherapeutic. He told Cameron Collins, his son and a fellow shareholder, who dumped his stock. Cameron then distributed the information to at least six other investors, who also sold the stock before news broke about the failed trial, dropping the stock price by 92 percent. All told, the defendants and their friends avoided over $768,000 in losses, according to the indictment.

The STOCK Act was intended to prevent members of Congress, who have access to all kinds of non-public information, from using their knowledge to make money for themselves and others. But Collins came by his information in a different, almost unbelievable way: He was on the board of directors of Innate Immunotherapeutics while also serving in Congress. Collins also held 16.8 percent of the company’s stock, and he was the company’s unofficial tout on Capitol Hill, getting at least six colleagues—including, at one point, former Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price—to buy shares.

Meanwhile, Collins sits on the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s health subcommittee, a position that gives him policymaking responsibilities over the pharmaceutical industry. As many Americans are learning for the first time today, there is no law prohibiting a congressman from serving as a corporate board member—even if that congressman specializes in policymaking that covers that corporation’s industry.

The details in the indictment are comical in the retelling of such naked corruption. When Collins learned about the failure of the multiple sclerosis drug trial, Innate Immunotherapeutics had halted trading on its shares at the Australian Stock Exchange, a routine circumstance when a company receives important news that they will later make public. But the U.S. over-the-counter market did not stop trading Innate, giving insiders the chance to financially benefit.

On June 22, 2017, Collins was at the White House Congressional Picnic when he got an email from Innate’s CEO about the “extremely bad news” from the clinical trial. Innate had put most of its hopes in the success of the multiple sclerosis drug, but it proved ineffective.

Collins got the email at 7:10 p.m. He wrote back, “Wow. Makes no sense. How are these results even possible???” Because Collins’s stock was held in Australia, where trading was halted, he couldn’t get his big stake out of the company. But his son Cameron had shares in Innate with a U.S. broker, which meant he could dump them.

From inside the White House, Collins immediately called his son, and they exchanged seven calls before finally connecting. Father and son had a short discussion, and the next morning Cameron began the first sale orders of what would eventually be a dumping of 1,391,500 shares, before release of the information on June 27. Cameron Collins also informed other shareholders, and at least six dumped their shares in Innate.

When news of the clinical trial failure broke, Collins’s spokesperson gave a statement to a local paper that “Cameron Collins has liquidated all his shares after the stock halt was lifted, suffering a substantial financial loss,” conveniently leaving out the 1.39 million shares Cameron Collins sold prior to that point.

While all this was going on, Chris Collins was already under investigation by the Office of Congressional Ethics, an independent watchdog, about his relationship with Innate. Collins was a co-author of the 21st Century Cures Act, which included provisions that would accelerate the approval process for drugs like the multiple sclerosis treatment being developed by Innate. He encouraged a National Institutes of Health employee to meet with Innate about its clinical trials in 2013.

Collins was also popping off to anyone who would listen about what a great investment opportunity Innate was, leading Republican representatives Markwayne Mullin, Billy Long, John Culberson, Mike Conaway, and Doug Lamborn to buy shares. Tom Price got in under a special discounted offer available to less than 20 people in the U.S. After being nominated for Health and Human Services secretary, Price sold his shares; it’s unclear if the others were tipped off. (Lamborn still owned shares as of last October—unfortunately for him, as they’re effectively worthless.)

The Office of Congressional Ethics released its findings in the Collins case last October, stating that “there is a substantial reason to believe that Representative Collins shared material non-public information in the purchase of Innate stock,” in violation of House rules and federal law. But they merely referred the matter to the House Ethics Committee, where it has sat; the committee didn’t even open a full-scale investigation.

One response to this is to say that all stock holdings from members of Congress should be held in a blind trust during their congressional service. There’s too much information floating around Capitol Hill that members can use to their benefit, and too much they can personally do to ensure that certain stocks spike or plummet in price. Congress should also close loopholes that let members participate in initial public offerings or discounted private placements of stock.

But the Collins case suggests an even more elementary restriction: Members of Congress should never be able to sit on a board of directors of a public company. The temptation to use the office to promote the company is far too great.

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty ImagesMuch of the Republican Party has long denied the science of climate change—that humans are causing the planet to warm. They’ve been less willing, historically, to deny the science of air pollution, which states that breathing in soot is bad for humans. But norms have changed since Donald Trump became president. For the last year and a half, fringe theories once promoted only by tobacco lobbyists and the very far-right have seeped into the offices of the Environmental Protection Agency. Now, those theories could soon be reflected in official EPA regulations intended to protect the public’s health.

A story published Monday in environmental policy outlet E&E News details the evidence. “After decades of increasingly strong assertions that there is no known safe level of fine particle exposure for the American public, [the] EPA under the Trump administration is now considering taking a new position,” reporter Niina Heikkinen wrote. “The agency is floating the idea of changing its rulemaking process and setting a threshold level of fine particles that it would consider safe.” (She’s referring to particulate matter that is 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter, small enough to penetrate deep into the circulatory system and potentially infiltrate the central nervous system. PM2.5 is the main component of soot.)

Under these changes, which are being considered by EPA acting administrator Andrew Wheeler, PM 2.5 would no longer be considered a “non-threshold pollutant”—one that causes harm at any level of exposure. Instead, it would become a “threshold pollutant,” or one that causes harm only above a certain exposure level. Wheeler is considering this change most likely because it would help him to legally justify repealing the Clean Power Plan, a set of Obama-era climate regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from coal plants.

Wheeler must prove that Obama’s policy would do more harm than good. Obama’s EPA had argued that the Clean Power Plan would reduce PM2.5 pollution, thus creating from $13 billion to $30.3 billion in public health benefits. This figure made up about half of the Clean Power Plan’s stated benefits. If Wheeler changes the official designation of PM2.5, the EPA’s position would be that breathing in small amounts of soot has the same impact as breathing in none. Thus, many of Obama’s predicted benefits would be erased.

This goes against nearly all mainstream scientific research on air pollution. But Wheeler might be able to make it official EPA policy anyway. That’s because in April, the EPA’s disgraced former administrator, Scott Pruitt, proposed a new rule to limit how science can be used at the agency. Championed by a former tobacco lobbyist, the rule prohibits the EPA from using research that includes confidential data about human subjects—effectively disqualifying much of the research showing how air pollution damages public health.

The scientific community is pushing back against the agency’s so-called secret science policy. On Tuesday, the entirety of Harvard University—its law school, medical school, school of public health, and all its teaching hospitals—wrote in an extensive letter that the “rule will wreak havoc on public health, medical, and scientific research and undermine the protection of public health and safety.” The school warned that the EPA’s rule could disqualify high-quality science that supports some of the EPA’s strongest regulations on lead, arsenic, hormone-disrupting chemicals, and—of course—air pollution.

Wheeler hasn’t yet decided whether the EPA will change its position on PM2.5. If he does, air pollution denial will become U.S. policy for the first time.

Ever since Justice Anthony Kennedy’s June announcement that he would retire from the Supreme Court, the spotlight has been on Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision legalizing abortion. Less than a day after the news broke, The Washington Post was reporting on the “real possibility” of abortion becoming illegal. Anti-abortion activists proclaimed that they were on the threshold of a historic moment: “In the history of the right-to-life movement, there has never been a more important time for us to come together and stand united,” Carol Tobias, the president of National Right to Life, wrote in a July newsletter. Kristan Hawkins, president of the group Students for Life, tweeted: “THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Whether Roe is overturned will in all likelihood depend on Donald Trump’s nominee to the Court, Brett Kavanaugh, a staunch social conservative. And if it is struck down in the coming years, what comes next? An emboldened anti-abortion campaign could lead to consequences for women’s health care and reproductive rights that range far beyond abortion restrictions. Contraceptive devices, such as IUDs or even the pill, could cease to be covered by insurance. But there is one procedure, in-vitro fertilization (IVF), that is curiously absent from this debate, though it results in the destruction of embryos.

Anti-abortion leaders are open about why they won’t go near it, revealing insights into the tactics and motivations of their movement. “It’s much more difficult to try to explain what is objectionable about IVF,” says Ann Scheidler, who founded the Pro-Life Action League with her husband in 1980. “You can only do what you can do with the resources you have, and we choose to really focus on the abortion issue.”

IVF poses a puzzling challenge for conservative groups: How do organizations that liken embryos to people reckon with a technology that creates babies for families, but destroys embryos along the way?

The first “test-tube” baby was born in 1978, meaning that not enough cyclical time has passed to comprehensively understand what will happen to most embryos that go unused during the IVF process. Some, for example, are frozen, ostensibly so they can be used at a later date. What’s clear, though, is that millions are rendered unviable. In other words: disposed.

Fertility treatments like IVF involve laboratory processes that combine extracted egg and sperm, then transfer the newly created embryos back to the uterus. If the embryo implants, the patient becomes pregnant. IVF in the United States has a live birth rate of 41-43 percent for women under 35, though that rate decreases with age.

But these successful pregnancies aren’t born of a single, perfect egg combining with a single, perfect sperm. One pregnancy results from the creation of multiple embryos, the amount depending on age and health of the patient, as well as sheer chance. Some cycles produce three embryos. Others produce 25. Dr. Nicole Noyes of the NYU Fertility Center estimates that 70 percent of all combinations she attempts manage to fertilize. Of these cases, she estimates 40 percent have viable, unused embryos after implantation, most of which are frozen. Other estimates are higher, and some say that almost half of viable embryos are eventually disposed of after being frozen.

Viable, unused embryos can be dealt with in a variety of ways. Freezing. Donation to research. Donation to another family. “Thawing” (a euphemism for disposal). The New York Times estimated in 2015 that as many as a million embryos could be frozen across the country. But many of those embryos remain just that—frozen, preserved—while outside the laboratory the families who created them raise children and go on with their lives.

Storage costs for frozen embryos can reach $1,000 per year, a cost that would seem prohibitive if it weren’t for the economic status of IVF’s typical clientele. An IVF cycle’s cost altogether adds up to around $20,000, and a 2011 study found that college-educated and higher-income patients were disproportionately using IVF treatments, thus achieving higher rates of pregnancy.

Even when families can afford to store their embryos, technology could still fail them. In the same week in March, the storage facilities of two fertility clinics—one in Cleveland, the other in San Francisco—malfunctioned, losing thousands of fertilized embryos. Lawsuits ensued, but on shaky ground. The losses, after all, were embryos the size of sesame seeds, most of which had undecided futures anyway.

But those same embryos—a varying amount of weeks further along, but unborn and largely undeveloped all the same—are also being extracted in abortion clinics. “There’s a disconnect between how public policy treats women who undergo IVF and women who have abortions,” says Margo Kaplan, a Rutgers law professor. When Kaplan herself underwent the IVF process, she says she was trusted with every decision regarding her embryos. She and her husband chose to donate theirs to medical research, an option for which Planned Parenthood has come under fire, but which has also aided essential research into Parkinson’s and other diseases.

Women who undergo IVF and choose to donate embryos do not have to read any mandated material or sit out a waiting period, both of which are required of women in many states who choose to get an abortion. “Nobody ever questioned my ability to make my own decision. And we don’t assume that women have the same ability to do that when they have an abortion,” Kaplan says.

Why the discrepancy? For one, the anti-abortion movement isn’t pushing the issue. “We’re making very great strides with regard to the abortion issue itself,” Scheidler says, while acknowledging that she doesn’t like that embryos are destroyed during the IVF process. “Why jeopardize that by adding something that’s going to be too emotional to be able to get people to pay attention and join us at it?”

But in being so cavalier about the fate of embryos that nominally bolster the ideology of their movement, anti-abortion activists reveal that the abortion question is really composed of a galaxy of issues that go beyond simply protecting the unborn. Kaplan thinks the reluctance to address IVF is related to a set of values the anti-abortion right holds close. “IVF doesn’t question the woman’s role as a mother,” Kaplan says. “Abortion tends to have to do with women who have had sex but don’t want to become mothers.”

That the stigma surrounding abortion is based on old-fashioned patriarchal values—ones that would deprive women of the freedom to make choices about their bodies and break from traditional conceptions of both family and sexuality—is apparent in the demographic data. Both men and the over-55 age group skew anti-abortion, while women and the 18-34 age group skew pro-choice, a 2014 Gallup poll shows.

Fertility treatments stand alone as a reproductive right that still reinforces conventional norms. Birth control leads to freer sexuality, to more career-focused women, and to further opportunities for disadvantaged women. IVF, on the other hand, favors women who are older, who have been married, who have graduated from college, who have a high income, and who are non-Hispanic white, according to a 1995 study.

So when the anti-abortion movement comes for reproductive rights, claiming to safeguard the right to life, IVF will likely be quietly ignored. The rise of fertility treatments is a positive development—lacking in equitable access, yes, but admirable all the same—yet this glaring gap reveals what Kaplan calls a “greater truth about the movement.” IVF is a treatment cloaked in privilege—both socioeconomic and normative—and if it thrives, it will be because of this.

Donald Trump’s antipathy to immigrants has been a defining feature of his rise to power and his presidency. He has focused much of that ire, personally and in his policies, on undocumented immigrants. But there are signs he wants to target documented immigrants, too. In February, Reuters reported that the Department of Homeland Security was “considering making it harder for foreigners living in the United States to get permanent residency if they or their American-born children use public benefits such as food assistance.”

A draft rule, which has not been released to the public, reportedly stated, “Non-citizens who receive public benefits are not self-sufficient and are relying on the U.S. government and state and local entities for resources instead of their families, sponsors or private organizations. An alien’s receipt of public benefits comes at taxpayer expense and availability of public benefits may provide an incentive for aliens to immigrate to the United States.”

These restrictions may now be close to fruition. On Tuesday, NBC News reported that Trump’s immigration policy adviser, Stephen Miller, is preparing a rule that would penalize documented immigrants for using certain public benefits: Use of food stamps, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or even Obamacare could cost a documented immigrant a green card or prevent them from gaining citizenship.

“Any proposed changes would ensure that the government takes the responsibility of being good stewards of taxpayer funds seriously and adjudicates immigration benefit requests in accordance with the law,” said a DHS spokesperson who confirmed that changes are in the works. Trump officials have sent the proposal to the White House Office of Budget and Management, the last step before the rule is released to the public for comment.

The rule is premised on the notion that non-citizens burden citizen taxpayers by taking welfare benefits or other public funds. But the evidence doesn’t support this. Not only is it extremely difficult to immigrate legally to the United States, it’s even more difficult to access benefits after doing so. A fair examination of the evidence points to one inescapable conclusion: Trump’s policy isn’t intended to shore up the welfare state for citizens, but to undermine it by reducing immigration.

The administration’s explanation for these proposals are the latest chapter in the longstanding, racialized disdain in America for welfare recipients (of which The New Republic itself has been guilty). The specter of the welfare queen still looms large in conservative imaginings, and now Trump has added immigrants to this bogeyman. “At its core, Trump’s [immigration] rhetoric is the same as Ronald Reagan’s 1976 campaign against ‘welfare queens’ that’s reared its head in just about every election since,” CityLab reported in 2015, after Trump’s campaign hit full swing.

In recent years conservatives have pushed the notion that immigration threatens America’s public resources. “Most of these illegals are drawing welfare benefits, they’re sending their kids to school, they’re using the public services,” Tom Delay said in 2016, though he conceded most still pay taxes. The Center for Immigration Studies, an anti-immigration think tank founded by a eugenicist, claimed on its website that households headed by immigrants, both documented and undocumented, “make more extensive use of welfare.” Trump’s reliance on CIS’s analysis is well-established. As Laura Reston previously reported for The New Republic, Trump has repeatedly cited CIS’s data and analyses in speeches, and in return, CIS has consistently defended the administration’s immigration restriction.

Immigrants, legal and otherwise, actually pay billions of dollars in taxes per year, though they often aren’t legally eligible for a full range of welfare benefits. States have some discretion, and can expand access to welfare if they choose, but generally, permanent residents can receive means-tested welfare benefits like Medicaid only after five years of residence in the United States. Documented migrants who have temporary status aren’t eligible for any benefits at all.

It’s particularly strange that the Trump administration reportedly sees Obamacare use as evidence of an immigrant’s welfare dependency; Obamacare allowed states to expand Medicaid, but in states that have chosen not to take advantage of that benefit, it only subsidizes private health insurance. Beneficiaries often pay hundreds of dollars out of pocket for premiums every month. It’s hardly a universal entitlement for anyone, let alone immigrants.

There’s no evidence that immigrants take up disproportionate space in America’s pool of welfare beneficiaries, either. Existing welfare restrictions tend to work as intended. As Vox noted in 2017, CIS skewed the data. Its analysis compared immigrant-headed households directly to citizen-headed households, without considering discrepancies in household size. Immigrants tend to have larger families, and their households therefore often include citizen children. When an immigrant-headed household participates in the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, formerly called food stamps, those benefits go to everyone in the household, citizen and non-citizen alike.

When researchers at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, examined CIS’s data set, they produced different results. “Overall, immigrants are less likely to consume welfare benefits and, when they do, they generally consume a lower dollar value of benefits than native-born Americans,” Cato concluded. “Immigrants who meet the eligibility thresholds of age for the entitlement programs or poverty for the means-tested welfare programs generally have lower use rates and consume a lower dollar value relative to native-born Americans.” Another report by a different libertarian think tank, the Niskanen Center, supported Cato’s conclusion: Low-income immigrants are less likely to use means-tested benefits like SNAP, Supplemental Security Income, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Immigration may even be a way for Trump to kickstart the economic growth he’s promised to deliver. A 2016 analysis by the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania found that there are long-term economic benefits to immigration, with few downsides. Immigration doesn’t depress the wages of native-born workers, and while it does increase the pool of available labor, that trend is matched by another: Immigrants spend money, which in turn grows the economy. And if American birth rates continue to decline—last year marked a 30-year low—there’s even less reason to restrict immigration. Without immigrants to ensure America’s population growth, aging Americans could find themselves in need of a welfare state with too few taxpayers to support it.

The probable benefits to the welfare state aren’t the only or even the most important impact of immigration, as Alex Press recently noted at Vox, but it’s undeniable that an aging population of Boomers, Gen Xers, and eventually Millennials may find themselves reliant on a welfare system that lacks the tax base it needs to survive. This impending threat might not trouble the Trump administration, or Republicans who view welfare as a pernicious drain on public resources. But in fulfilling his promises to restrict immigration, Trump may sacrifice America’s economic health.

On Monday more than 25 opposition groups flooded the streets of colonial Potosí to disrupt the government’s official celebration of Bolivia’s independence day. It had snowed in the city on Saturday, and melting snowmen decorated the main plaza.

Alongside the national army and Congress there for the official events, hundreds of people turned out to protest President Evo Morales’s plans to run for a fourth term in 2019. His bid was announced in late November 2017 despite a national referendum opposing a constitutional amendment to grant him another term.

The protesters had wanted to fall in amongst the official government parade held in the morning, according to Bolivian newspaper El Deber. Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, by 7 a.m. all entrances into the plaza were blocked by police barricades. Only pre-registered organizations and people with press credentials were allowed to enter. “We are not even allowed entrance into our own independence day ceremonies,” muttered one indigenous woman angrily, as she pushed past me in her pollera, a traditional Quechua skirt.

Inside the plaza, a more modest crowd waved blue cardboard thumbs-up hands that said “Bolivia dice sí”—“Bolivia says yes.” Yes to the re-election, that is.

The morning ceremony was relatively uneventful, with the expected military parades followed by Vice President Álvaro García Linera’s address and Evo’s state of the union. The real action picked up after the official ceremonies were over: After the military parades and addresses from the president and vice president, the police barricades were disbanded, which allowed protesters to flood in with massive “BOLIVIA DIJO NO” banners—“Bolivia said no.” No to the re-election, no to Evo’s Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Towards Socialism, MAS) party, no to the addresses that had been made by Evo and Linera less than an hour before.

Bolivian President Evo Morales on August 7, 2018. Diana Sanchez/ AFP/Getty

Bolivian President Evo Morales on August 7, 2018. Diana Sanchez/ AFP/Getty By many metrics, Bolivia has seen remarkable progress under President Evo Morales, popularly known as Evo. The country’s “first indigenous president,” as Linera emphasized to the crowd on Monday, can boast of achievements in economic growth, literacy rates, improved public health, and education initiatives—to name just a few. “We are in Bolivia’s golden age, and it is defined by progress, production, and a digitalized youth,” said Linera.

Evo came to power in 2006. Following on the heels of a string of neoliberal, U.S.-backed presidents who struggled to maintain order without resorting to violence, his tenure has marked a new era of Bolivian politics—especially because he kicked out the U.S. embassy and refused all U.S. aid when he first entered office. And as he stretches for a fourth term, the president has emphasized this contrast between him and his predecessors. “The nationalization of our natural resources instead of privatization—that is one grand difference between us and them,” he gave as one example. He also praised “Bolivia’s incredible working class” to cheers from the crowd.

But perhaps most strikingly, during Evo’s presidency Bolivia has made unprecedented strides for indigenous rights. Indigenous peoples have been marginalized for almost all of Bolivia’s colonial and modern history. Parents chose not to teach their children their native tongue to protect them. Bolivia was one of the poorest countries in the world, and its majority-native population were the poorest of the poor.

Under Evo’s new constitution in 2009, things began to change. The official name of Bolivia changed from “The Republic of Bolivia” to “The Plurinational State of Bolivia”, plurinationality recognizing the diverse array of nationalities within one state polity. Thirty-six indigenous languages were recognized as official.

The plurinationality of the new constitution seeped into many sectors of modern Bolivian life, such as education and public offices. The 2010 education law, titled Ley 070, required all school children to learn not only Spanish and “a foreign language” (usually English), but also the native language of the department in which they live. Currently, 34 of the the 36 officially recognized indigenous pueblos have their own language institutes located within their own communities. As of 2012, every public official has been required to speak not only Spanish but also the native language of the region in which they work. For the first time in Bolivian history, a woman can walk into a bank in La Paz and converse with her teller in Aymara. A man can walk into a hospital in Cochabamba and receive treatment from his doctor in Quechua.

These policies, and many more, have changed the lives of millions of indigenous peoples in Bolivia. “Now in professional offices you see a woman wearing a pollera,” a woman said to me during the protests Monday afternoon. “That never happened before Evo. Now people like me are ministers in the government. That’s why I am a MASista, until I die,” she said.

On Monday, Evo ended his speech pointing to the global significance of his Bolivian experiment: “With all of our economic growth, Bolivia has a lot of hope. But what has been perhaps one of the most important changes? Bolivia has begun to be recognized internationally.”

Regardless of where you fall on the merits of Bolivia under Evo, this statement is undeniably true. A leftist experiment appearing to resist the scripts set by Cuba and Venezuela, Bolivia has set a precedent, and the world is watching.

Bolivia’s 2009 constitution, however, also limits presidents to two terms—which Evo has now served, in addition to his term prior to creating that constitution. And in February 2016, voters across the country rejected Evo’s proposal to change the term limits, 51.3 to 48.7 percent.

The opposition groups that travelled to Potosí on Monday are part of the “F21 2016 Movement”—named for Feb. 21, 2016, the date of that referendum vote. However, in November 2017 Bolivia’s constitutional court annulled the referendum and struck down re-election limits on all public offices, claiming that re-election limits are a violation to human rights. A few days later, Morales announced his candidacy for the 2019 elections. If elected, he would remain in office until 2025, a term of 19 consecutive years.

The F21 2016 “Bolivia dijo no” movement has been growing ever since. In the week following the court’s decision, protests and blockades were staged across all major cities in Bolivia. That same week during judicial elections, over 50 percent of the ballots cast were null ballots—an apparent response from the opposition to intentionally cast null votes as a form of protest to Morales and his government. Throughout Bolivia’s major cities, such as Cochabamba, La Paz, and Santa Cruz, graffiti in full view declares “Mi Voto Es Valido” (My vote is valid) and “NULO” (Null).

This past Monday, the protesters held nothing back. “¿Si esto no es el pueblo, dónde está el pueblo?” (“If this is not the people, then where are the people?”) was one repeated chant, referring to Evo’s claim that he respects the people’s wishes. “No es Cuba tampoco Venezuela, Eso es Bolivia y Bolivia se respeta” (“this is not Cuba or Venezuela, this is Bolivia and you respect Bolivia”) was another. One especially strong one was “Muere muere Evo, Evo criminal” (“die, die Evo, Evo criminal”).

Some protestors were less harsh. People of all ages marched, many donning homemade “Bolivia dijo no” and “F21” shirts. Women marched with their babies. One woman had her child’s stroller decked out in “F21” memorabilia. I asked a nearby woman why she thought so many people still support Evo, and she turned to me and said: “Those people have clearly not lived what we have lived. We have nothing, Evo has not helped us. And we are sick of it,” she said. In her view, Potosí remains impoverished, especially in the countryside.

Beyond specific grievances with Evo’s policies, many are also concerned about what an ignored referendum means for the state of democracy in Bolivia—and a democracy that has close ties to Cuba and Venezuela, the latter which under Hugo Chavez and his successor Nicolas Maduro has become what appears to be a failed state.

“Bolivians, across all economic classes, are nervous about the implications of a President who is directly ignoring a vote of the people that he himself called for. They see the rise of violent authoritarianism in Venezuela and Nicaragua and wonder if this will be their country’s future as well,” said Jim Shultz, an activist and co-author of a book about Bolivian indigenous resistance to globalization, who recently returned from Bolivia to the US after living outside of Cochabamba for 20 years.

In Potosí, the opposition appeared diverse and not necessarily unified. Ranging from groups called “Another Left is Possible” and “Bolivia Promised Me” to mining syndicates and coca leaf farmers from the lowlands, they declared their support for F21 from a diverse array of ideological and political motivations.

Many of the opposition come from the left, claiming that Evo has failed to keep his promises as a truly decolonial and anti-extractivist president. Evo has opened up the country to massive mineral exploration—particularly to Chinese companies—despite claiming to be dedicated to the “Rights of Mother Earth”. Dam projects in the Amazon on the Bala and Beni rivers have been approved by the government, despite indigenous protest. For many, the construction of the national highway in the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS) despite indigenous and international protest was the final straw. How pro-indigenous and anti-capitalist, leftist critics ask, is Evo and his administration, really?

Linera ended his speech by quoting Karl Marx and declaring that “capitalism has brought blood all over the world”—a nod to the millions of indigenous people that have died in Potosí’s silver mines since the colonial period and are still dying today.

“There is not another future,” he said. “If there is something different, it is a cliff—it is the return to neoliberalism. The abuse of water and gas. The privatization of natural resources,” he said, referring to the Cochabamba Water War of 2000 and the El Alto Gas Wars of 2003 that ultimately led to the resignation of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada “Goni” and Evo’ selection. “The Agenda 2025 is the only option,” he declared to a cheering crowd, referring to the prospect of Evo being in power until 2025. Revolution, according to this line of thinking, is tied to a particular man and his necessary re-election in 2019.

“The insistence on re-election at all costs is a sad development for Morales and his legacy,” said Schultz “His presidency has been historic and has accomplished a good deal, but ignoring the basic rules of democracy will put a stain on that, and maybe worse.” The protesters who flooded the square following Linera’s and then Evo’s speeches seem to agree.

Can Bolivia have a government in which all public officials speak their own indigenous languages, but not because it is required by Evo? Can its teachers imagine a Bolivia in which their students learn within tri-lingual, decolonial classrooms that are not funded by the MAS party?

Can the revolution live beyond a man? Many Bolivians want to find out.

No comments :

Post a Comment