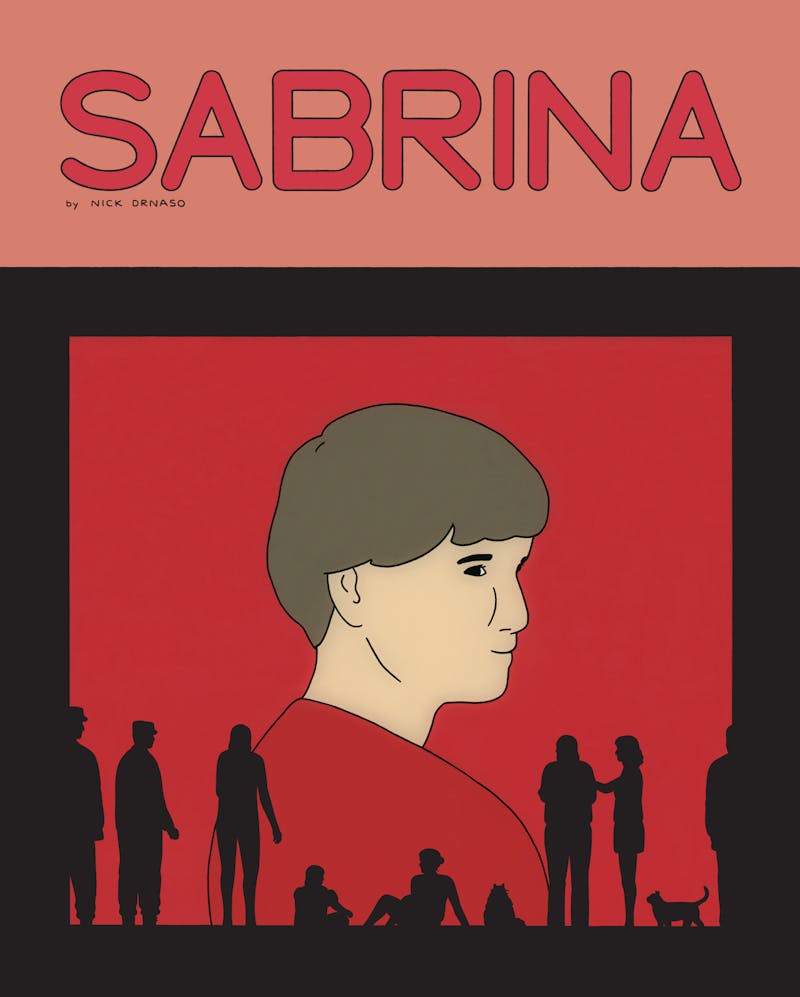

In July, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina became the first ever graphic novel to be nominated for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction. The nomination—even on the longlist—feels like an event: What kind of book using pictures would be sophisticated enough to compete with the usual Booker fare of prestige prose? A lesser work would have undermined this genre-bridging nomination, making it look like a stunt. But Sabrina—short on words, big on humanity, succinct of plot—is not a lesser work.

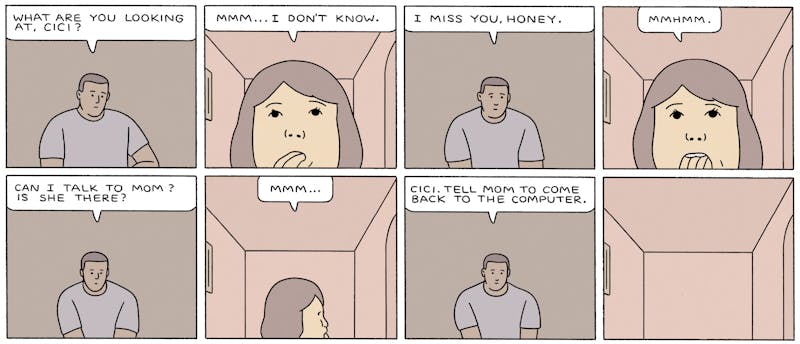

On the first page, we see Sabrina herself in a large top panel. Her expression is difficult to read. Like all of the characters in the book, her eyes are just dots, her mouth a line. She is reminiscent of an old-fashioned airplane safety manual person. Below, six panels show her wordlessly looking around her house for ... what? She peers down the hallway and into the bathroom and then, on the next page, under the bed—where her cat is hiding. The scene exudes the specific quiet of being home alone. Her sister, Sandra, comes over and they have an extraordinarily naturalistic conversation. “It was good to see you,” “You too,” and “See you later” all get their own panels. Then, quiet again.

There are a lot of pages without any words on them in Sabrina. No commentary, no thought bubbles.

The story that plays out across its 204 pages is simple, brief even. But the book takes its length from its pacing. Nick Drnaso moves his story at the speed of ordinary human life. In the real world, it takes about six panels to get ready for bed, and nobody talks while they do it. Events both small (conversations) and large (tragedies) do occur, but so do the many interstitial hours we spend alone, driving or just thinking. In this sense Drnaso’s scenes play out like the opposite of an old-school comic. In the work of Aline Kominsky Crumb, say, life is sped up and boiled down and whipped into crackling humor. But Drnaso takes it slowly, and that’s what makes it feel like a novel.

After the opening sequence, we turn abruptly to Teddy and Calvin. They are old friends from high school. Teddy is Sabrina’s boyfriend, we read, but Sabrina has gone missing. He’s losing his mind with stress and Calvin takes him in. Teddy stares at the wall and does nothing. Calvin brings Teddy home a hamburger every night. He works for the military in systems security, which means that each day Calvin fills out a psychological health checklist that asks: How many hours of sleep did you get last night? He has to rate his stress level from 1 to 5. He has to say whether or not he is having thoughts of suicide. It is as if the military is asking Calvin to put together a crappy comic book version of his inner life. He fills out the boxes.

SABRINA by Nick Drnaso.Drawn & Quarterly, 204 pp., $32.95.

SABRINA by Nick Drnaso.Drawn & Quarterly, 204 pp., $32.95.Sabrina has disappeared. Then it turns out that Sabrina has been killed. Teddy stays with Calvin, Calvin helps Teddy, Sandra tries to adjust. These are small people dealing with a blow so big and so bad that it would fit better in a horror movie. Drnaso writes the murder, however, in order to trace its fallout.

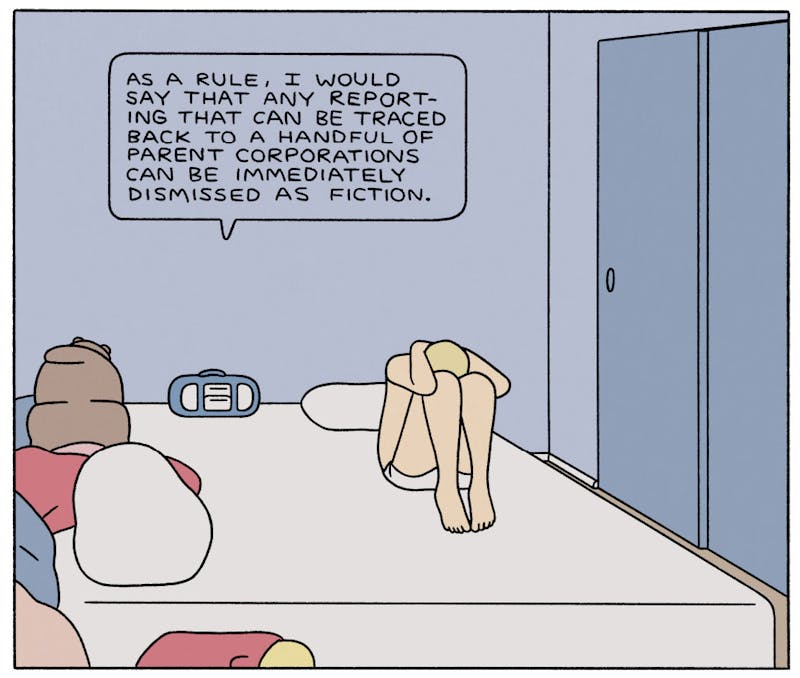

The world does something strange with Teddy’s loss. He spends his days horizontal in Calvin’s spare room. Out of a radio in that room a voice appears. He listens to the voice griping about conspiracy theories, false flag operations. He seems to find some comfort in hearing this crazy right-winger grieve for the fate of America. “Our masters will flee to their compounds, leaving us to endure unimaginable plagues and ‘natural’ disasters,” the voice laments. “Sometimes I hope I don’t live to see it.”

Sabrina’s death, unfortunately, has been both violent and captured on camera by a killer intent on turning his crime into personal notoriety. Drnaso draws websites and listicles and comment sections. He draws the way that Teddy’s personal devastation becomes just another piece of news-cycle flotsam, seized by readers eager to find some secret narrative behind the simple, sad one.

After journalists turn up at Calvin’s house to look for Teddy, an image of Calvin in his camouflage gear shows up on the internet. Online whispers flourish into full-on conspiracy theories. Was the army involved in Sabrina’s death? Did Sabrina ever exist? Calvin is subjected to Sandy Hook truther–style scrtiny, but he doesn’t really say how he feels about it. The radio that had seemed like Teddy’s only connection to the world has circled back to victimize him. We just see him lie on the ground.

Nick Drnaso / courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.

Nick Drnaso / courtesy Drawn & Quarterly. The nasty conspiracy theorists of Sabrina exist outside the radio, too. Calvin’s colleague warns him against taking a mysterious new job, claiming that all kinds of “black ops” secret government terror is lying in wait for him. It’s just an expressionless drawing on a page, but the switch of this character from buddy coworker to deranged truther is frightening.

That fear comes from the way Drnaso has chosen to tell this story. These characters’ bodies act out the plot: We see where they go, what they’re doing. But their faces don’t teach us what they feel. It’s as if we are navigating a world with prosopagnosia (face blindness) and relying only on speech for clues, for patterns that give sense to the world.

The plot stakes of Sabrina are almost lurid: abduction, murder, conspiracy. But it is a gentle book. A great deal plays out inside cars, living rooms, bedrooms. The quietest and saddest panels in this quiet and sad book are the drawings that contain no people at all, like the Skype window after Calvin’s daughter has run out of frame, or a park with nobody in it. These scenes make the difference between absence and presence very clear. A person is there, or a person is not. It’s not complicated. Death is so basic and so powerful that we think up conspiracies to impose sense on it. Sabrina is a political book, in many ways, because it looks at the madness we provoke in each other on the internet. But it is also about walking through a room and then leaving it.

Nick Drnaso / courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.

Nick Drnaso / courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.

What is it about Canadians that irritates Arab leaders? At the end of last week the Canadian foreign minister made a rather direct call for the Saudi government to release some recently detained Saudi civil rights activists. The Saudi response was instant and intemperate.

Riyadh suspended flights, threatened trade, sent the Canadian ambassador home, and ended scholarships for Saudi students in Canada (which surely hurts these students as much as it does Canadian universities).

It was not the first time that Canada has provoked an angry reprisal from a Middle Eastern ruler. In 2010, frustrated by Canada’s refusal to agree new landings rights agreements for its commercial airlines to Toronto, Vancouver, and Calgary, the UAE’s rulers swiftly booted Canadian troops from their logistics base in the Gulf nation.

In both cases the responses were so disproportionate you suspect that the rulers in question took the Canadian affront a little personally. (It would be easy, here, to crack a joke about Canadians’ worldwide reputation for niceness, although in the strange world of diplomatic disputes it wouldn’t be the first time something this trivial had given an opposing side the wrong idea.) In fact, in speculating about the cause of the current crisis between Canada and Saudi Arabia—and absent a candid interview with the key Saudi decisionmaker, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MBS), all we can do is speculate—we should not lose sight of this personal dimension.

Another possibility is that MBS is using the Canadian intervention in Saudi domestic affairs to stoke a bit of nationalism.Sometimes rulers in the region, who run their country’s like one would a family business, simply get annoyed. In any event, it would be hard to imagine such dramatic reprisals being conjured up by anyone other than rulers themselves; certainly not their more cautious officials.

Having said that, as a number of observers of Saudi affairs have ventured, there may well be some method here, too. One theory is that Canada is being made an example of; a warning to other countries that injudicious commentary on Saudi affairs could be an expensive exercise. Perhaps Canadian companies with business interests in Saudi Arabia are already pushing Ottawa to make amends.

Another possibility is that MBS is using the Canadian intervention in Saudi domestic affairs to stoke a bit of nationalism, not least to keep dissenting Saudis in line. It is noteworthy that the activists arrested in recent months have been labelled traitors and foreign agents on traditional and social media in the Kingdom. A bit of nationalist clamouring is a great way to drown out dissent.

If either of these theories is correct it would be another interesting data point on MBS and his reformist agenda. Some analysts have been too quick to dismiss the young tyro and his reformist plans. I think he is serious about refurbishing the ruling system and Saudi society, not least to keep himself and his family at its head.

Like others in the region, that system is starting to seize and splutter, even if it’s better lubricated than most by its oil wealth. And in many ways, MBS is not so much reforming the country from top-down as responding to the demands of Saudi society for change that have been building for many years.

But herein lies the problem for MBS. He may well fear that in reforming the country he could loose ideas and forces that he will not be able to fully control. The arrests of leading women’s activists over recent months just when he was introducing some of the very reforms they had long advocated—such as the right to drive—might be read as a message that he, and only he, will dictate the pace of reform.

But he probably also understands that like greater historical reformers of the modern Middle East—from Attaturk in Turkey to Gamal Abdel Nasr in Egypt—he needs to mobilize his people if he is to truly transform his country and its society.

In this regard (and at the risk of being accused of interfering in Saudi Affairs), an argument could be made that the best way to do this is to empower and mobilize the very women that he has been locking up of late.

Many Saudi women are highly educated. Many also don’t work—or work in limited sectors—because of cultural, legal or practical barriers (such as, until recently at least, not being allowed to drive). Like the vast oilfields that transformed Saudi Arabia after World War II, tapping this enormous economic and intellectual potential could rapidly change the country’s economic future—precisely what MBS has said he is trying to do with his reforms.

By contrast, mobilizing Saudi nationalism, especially by preaching to anti-foreigner instincts, as increasingly popular as such a strategy might be around the world these days, will offer some short-term advantages. But it could also prove counterproductive in all sorts of nasty ways.

One episode in the current Saudi drama with Canada possibly highlights that danger. As the dispute erupted, a Saudi youth group took aim at Canada on Twitter with what it claimed was an Arabic proverb: “He who interferes with what doesn’t concern him finds what doesn’t please him.” More menacing than the proverb was the image accompanying it: a Canadian airliner seemingly on a collision course with Toronto’s CN Tower.

The offending tweet was condemned by Saudi officials, and promptly taken down by the group that published it. The latter claimed that the intent of the image had been misconstrued. Maybe the intention was innocent. But just the possibility that it wasn’t should be alarming to Saudi authorities—as it clearly was to those officials who swiftly censured it.

Even if it was just a bit of youthful macho posturing, it is something Saudi Arabia’s international image could do without, especially as it tries to attract foreign investment. Then again, the same might be said of the indignant way that Saudi Arabia’s rulers have handled their contretemps with Canada.

What does it take to get banned from Facebook? In the case of Alex Jones, quite a bit. Jones, the proprietor of InfoWars, pushed the PizzaGate conspiracy that led to a gunman firing an AR-15 through the ceiling of a Washington, D.C., restaurant. He has claimed that “no one died” in the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre. He has claimed that the “Jewish mafia” controls a number of powerful entities, including the American health care system, and that several prominent Democrats are demons posing as human beings. A week ago he mimed shooting special counsel Robert Mueller, who he has called a “demon,” a “pedophile,” and the head of a Deep State conspiracy against President Trump.

Jones has amassed sizable audiences across multiple platforms, which he uses to push insane conspiracy theories and dubious dietary supplements. Jones’s YouTube page alone had 2.4 million subscribers as of this week. But in response to a rising drumbeat of calls for Jones and InfoWars to be banned, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Facebook all pulled the plug on Jones on Monday. Apple led the way and Facebook followed soon after, with both outlets citing Jones’s “hate speech.” YouTube has largely stayed quiet about its decision to ban Jones, but has suggested that unspecified violations to its Community and Service Guidelines are responsible. Twitter is, as of this writing, the only social network where InfoWars still has a platform, while Facebook has indicated that Jones can appeal its decision.

Is Jones’s ban an indication that Silicon Valley is finally purging toxic sites like InfoWars? Or are tech companies doing the bare minimum to free themselves from what they see as primarily a public relations problem? The difficulty they had in banning Jones suggests the latter. Furthermore, it shows that, even if Silicon Valley truly wanted to get clean, there are limits to managing the speech of unimaginably large platforms composed of hundreds of millions of users.

The bans on Jones came in a flood, but they weren’t coordinated. It seems that Facebook and YouTube were waiting on some other company to ban Jones first. When Apple made its move, they followed in quick succession. Facebook had, until recently, defended Jones’s right to make statements that were destructive and demonstrably false. Asked by Kara Swisher last month about the conspiracy theories that outlets like InfoWars circulate on Facebook, CEO Mark Zuckerberg suggested that he was fine with Holocaust deniers using his platform because they might earnestly believe that Nazis did not systematically murder millions of Jews. (He later apologized.)

Free speech has become an increasingly thorny issue for Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube (which is owned by Google), particularly after the election of Donald Trump. With conservatives claiming that they have been unfairly targeted by tech companies, Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey have attempted to curb the backlash by presenting themselves as champions of free speech. Squeezed by angry conservatives spoiling for a culture war on one side and investors demanding constant user growth on the other, Facebook and Twitter have indicated that they are open to just about everyone—including frauds like Jones.

The decision to ban Jones, then, is an indication that concerns about hate speech, conspiracy theories, and fake news are being taken seriously—or at the very least, that these concerns can be serious PR headaches. Previously, the threat of a vocal and organized response from right-wingers—who are up in arms about Jones’s ban—would have spooked Facebook and YouTube. Twitter, the lone holdout, is now in a strange position. With all of its peers having kicked Jones out, keeping him on the platform (where he is verified) looks an awful lot like an endorsement.

To be fair to Twitter, Jones has hardly been silenced. The InfoWars app is still available from the Apple store and Android’s Google Play. Jones has high-profile defenders in right-wing media, like Matt Drudge, and may very well become a cause celebre for conservative politicians who are courting the far right, like Senator Ted Cruz, who has attempted to walk a line in which he protects the conspiracy theorist’s “free speech” without explicitly endorsing the crazy stuff he has said. Cruz even appropriated a famous poem about the Holocaust to defend Jones, saying, “You know how the poem goes, First they came for Alex Jones…”

But the pressure on Facebook, YouTube, and others to block Jones had reached a critical mass. These companies were faced with two options they did not care for: Either ban Jones and deal with a backlash from the right or keep him and deal with a backlash from those demanding that they not facilitate the spread of conspiracy theories that not only mock the deaths of massacred children, but also result in real-world violence. It’s now clear that Facebook will remove a dangerous hatemonger if a lot of people demand it.

It’s not clear, however, if it will swiftly remove a figure of Jones’s ilk without a larger public campaign. The problem with Jones is a problem with enormous social media platforms in general. WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook—all owned by Facebook—have a combined 2.5 billion users. Five billion videos are watched on YouTube every day. These companies have grown so large that they can’t effectively regulate speech.

Their incentives, moreover, point in the opposite direction. These companies try to cater to the interests of all of their users, which is how people like Jones thrive in the first place. And in his Holocaust comments, Zuckerberg did get at something true: Facebook doesn’t technically have a responsibility to suppress hateful speech. The InfoWars mess is symptomatic of an industry that has grown too large and unruly, with an outdated legal and regulatory framework that both under-regulates platforms and gives them little motive to self-regulate. Jones and InfoWars may be barred from Facebook. But the problems that they represent are here to stay.

On April 3, President Donald Trump sat down to a private dinner with some close associates, including Peter Thiel, his most loyal supporter in Silicon Valley. Thiel had brought Safra Catz, the co-CEO of Oracle, along to discuss a $10 billion Department of Defense contract to build the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure, or JEDI, a cloud computing platform that will eventually run much of the Pentagon’s digital infrastructure—from data storage to image analytics to the translation of intercepted phone calls. According to Bloomberg News, Catz objected to the DOD’s plan to award the entire JEDI contract to a single organization, rather than parceling it out to multiple contractors. Oracle, Microsoft, and IBM were all bidding, but Amazon, Catz said, with its massive cloud services business, had an unfair advantage. (Trump, in a rare display of restraint, reportedly said he wanted to ensure a fair competition but went no further.)

JEDI plays a significant part in the Pentagon’s strategy to ensure that its war-waging capabilities keep pace with technological change, and Amazon is probably best positioned to build it. The company’s web services division (AWS), officially founded in 2006, grew out of a project hatched by two of its employees, Benjamin Black and Chris Pinkham, to use Amazon’s growing resources to provide technical infrastructure to anyone who might want it—whether a retailer selling their wares through Amazon’s platform or someone starting a new company. The initial product, called EC2, helped Amazon launch an entirely new industry, broadly called cloud computing but encompassing a range of services, including data storage, analytics, machine learning, and other tools. While Amazon’s vaunted retail business frequently lost money over the last decade, AWS has been one of its most reliably profitable divisions, bringing in $5.4 billion in revenue in the first quarter of 2018.

Microsoft, Google, and others eventually started their own cloud computing divisions. But as the competition over JEDI shows, the desire to challenge AWS has led major technology firms into the national security complex, with promises to analyze imagery for drone strikes and to run communications links for soldiers fighting in the Middle East and North Africa. As these companies move into military work, their claims about the benevolent role that technology can play in modern society—already damaged by scandals ranging from Uber’s labor exploitation to Facebook’s electoral mismanagement—are running squarely up against the realities of their profit motive.

In truth, government and the technology industry have always been partners. Some companies, like IBM, have relationships with the military that extend back to World War II. The development of the early internet owes much to resources provided by the Pentagon’s advanced research division, an agency founded in 1958 to counter Soviet expansion into space. Later, during the Cold War, microchips developed by industry pioneers like Fairchild Semiconductor found their way into ballistic missiles. Even Stanford University’s rise as an engineering and entrepreneurial powerhouse depended heavily on millions of dollars in government funding for high-tech research (a relationship that became controversial during the Vietnam War).

More recently, Edward Snowden’s 2013 leaks revealed the tech industry’s complicity in the National Security Agency’s global surveillance operation. Major companies had complied with—and profited from—government demands for unwarranted data collection. In one telling detail made public by Snowden, Americans learned that even as the NSA was making secret deals with Yahoo and other companies to access customer information, the intelligence community was hacking into those same companies and collecting personal data.

With the exception of a few notable court challenges to government subpoenas, the Snowden leaks did little to change the industry’s close relationship with the military. Silicon Valley executives like Eric Schmidt still sit on Pentagon advisory boards, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos entertains strategically important heads of state like Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Despite Mark Zuckerberg’s ritual shaming before a congressional committee this past spring, the quasi-governmental reach of these companies remains self-evident.

Take Palantir, perhaps this era’s paradigmatic tech company, if not also its most controversial. Established in 2004 by Peter Thiel—Trump dinner companion, PayPal co-founder, Facebook board member, and slayer of Gawker Media—Palantir organizes and parses vast amounts of data for corporate and government clients, particularly in the defense and intelligence communities. Considered one of the country’s most valuable privately held startups, Palantir was initially funded partly by In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital arm. This government pedigree has ensured that its products are as popular in Washington as they are in Kabul, where they’re used to track the locations of improvised explosive devices.

Palantir’s lucrative government contracting business is perhaps more overt than some of the other tech giants’, but it’s far from an outlier. Amazon, whose AWS division provides the digital infrastructure for everything from NASA to Netflix, is already the official cloud-computing provider of the CIA. Even before it began competing for JEDI, the company provided similar services to the Defense Department and other government agencies as a subcontractor. Microsoft’s operating systems power millions of DOD devices; in 2016, it earned a $927 million information technology and consulting contract from the department, and in May it announced a deal to provide its Azure Government cloud service to the 17 U.S. intelligence agencies. Google has dipped into government contracting, too, though not without internal resistance. This spring, more than 3,000 Google employees signed a letter of protest, and roughly a dozen resigned, in response to the company’s participation in Project Maven, which provides image analysis technology used in drone strikes to the Air Force. (Google announced in June that it would not renew the contract.)

Meanwhile, Amazon has attracted a great deal of scrutiny for its enduring march toward retail monopoly, but in reality, the company’s future now rests as much in securing the top-secret data of CIA activities as it does in delivering groceries—a spectacular broadening of its reach, which ought to bring up questions about whether Amazon’s market share buys it the same leverage in the federal government as it does in the retail economy.

It should perhaps come as no surprise that the government, for its part, would seek out the data and expertise of Big Tech. (Former Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter held regular meetings with Silicon Valley VIPs while serving in the Obama administration.) Only the large firms have the capacity to build and manage the secure databases and sophisticated computer networks that governmental bureaucracies need to operate. And these companies, in collecting so much user data, present a tempting opportunity for intelligence agencies looking to expand the scope of their mass surveillance; the NSA and others want the same data these companies collect in the normal course of business. But that doesn’t mean that the technology companies are obliged to respond to the call for government cooperation, nor do they necessarily need to rush willingly into the defense industry.

Much has changed since the first ties between the government and technology companies were forged during World War II. Today’s tech giants have immense influence over everything from social media to restaurant reviews, autonomous vehicles to health care. They are some of America’s most valuable, and often most admired, companies, with interests deeply intertwined with the global economy. And while contracts like JEDI may comprise a growing share of their profits, the government probably needs tech firms more than they need the government. Because the DOD and others rely so heavily on their tools, they could, in theory, resist invasive data requests. They have the power, and the ethical obligation, to decide what kind of companies they want to be and, increasingly, to help decide what sort of country the United States should be.

Big Tech increasingly has the power, and the ethical obligation, to help decide what sort of country the United States should be.That, ultimately, is why the fight to win the JEDI contract represents something larger than the profit margins and stock prices of Silicon Valley firms: It is a crossroads at which tech companies will be forced to choose whether they can feasibly continue to preach the values of liberal-minded innovation and independence from big government while serving as its well-paid and compliant partners. It may be unrealistic to expect large, profit-seeking corporations—the Everything Store exists to create loyal consumers, after all—to decline work that’s both wildly remunerative and earns them outsize influence with the very entities that wield the power to regulate them. But it is fair to expect that these companies would act with the ethical standards they so proudly claim to uphold. In recent years, monopolistic tech giants have reaped fantastic gains in efficiency and cost savings, often at the expense of individual privacy and labor rights. To add “war profiteer” to that list would only further diminish an industry that, with equal parts naïveté and swagger, has so often failed at trying to do good.

“I promise to these younger kids and younger generation that I’ll continue to be a role model to them and I’ll continue to lead by example,” LeBron James said in 2013. James kept his promise.

Last week, the basketball star opened the I Promise School in his hometown of Akron, Ohio. A joint project of James’s foundation and the local school district, the school differs from other celebrity forays into education in key ways. Notably, it isn’t a charter school, which would be privately run. Instead, I Promise is a public school under the jurisdiction of the Akron school district, so it’s subject to the same regulation and oversight of all public schools. And as Education Week reported, I Promise shares DNA with the community school model, which envision schools as centers where community members can receive wraparound social services in addition to a K-12 education.

By eschewing the charter model, James not only avoids what many critics consider to be the privatization of education; he may also shore up the school system’s ability to address, rather than aggravate, existing inequalities. I Promise deliberately chose, via lottery, students with records of truancy or disciplinary problems, and will provide psychological counseling to both students and teachers.

Charter schools, by contrast, often enforce draconian conduct codes and can be quick to expel students. A 2015 investigation by The New York Times found that some administrators at Success Academy, a prestigious charter network in New York City, “singled out children they would like to see leave.” In April, NPR reported that Chicago’s Noble charter schools enforced such a strict disciplinary code that teenage girls regularly bled through their pants because their schools did not allot them enough time to use the bathroom.

Some charter schools, like the Harlem Children Zone’s Promise academies, provide wraparound social services that resemble those on offer at I Promise. But even at Promise academies, results are mixed. A 2014 study published by the Abdul Lateef Jamil Poverty Action Lab showed that students who won a lottery to attend a Promise school were more likely to finish high school, but Promise attendance didn’t correlate to improved mental and physical health, or to lower reported rates of drug and alcohol use. Charters also have variable academic outcomes overall, and they don’t reliably outperform public schools on average.

I Promise isn’t a typical public school, though. The school will employ 43 staffers for classes of 20 students each, a ratio lower than the city’s reported average of 23 elementary school children per teacher. It will also provide additional services for the at-risk elementary school students it serves: It will provide free bikes and laptops for students, run a food pantry for school families, offer GED classes and job search assistance for parents, and pay for students to eventually attend the University of Akron.

James isn’t the first wealthy person to try to shape public education by funding extra services. Sarah Reckhow, a professor of political science at Michigan State University and the author of Follow the Money: How Foundation Dollars Change Public School Politics, cited Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff. “He has given hugely to the San Francisco public schools as well as other public schools in the Bay Area, and has had a pretty dramatic impact,” she told me. “The Mark Zuckerberg grants to Newark involved quite a bit of money to the traditional public schools.”

Zuckerberg’s $100 million grant, announced in 2010 on an episode of Oprah with then-Newark mayor Cory Booker, and later matched by another $100 million in donations, did reshape public education in Newark. The state of New Jersey, which had controlled Newark city schools since 1995 due to underperformance, closed 14 struggling public schools and laid off hundreds of teachers. The New Yorker’s Dale Russakoff reported in 2015 that $20 million of the funds went to consulting firms. A recent study (funded by the Chan-Zuckerberg Foundation) found more positive academic gains in English for Newark students at charter schools whose enrollments increased after the grant; but it didn’t examine social or health outcomes.

Benioff and Zuckerberg are both part of a wave of Silicon Valley billionaires funneling money to traditional public schools, but according to a 2017 story in The New York Times, they face limited oversight, and there’s little research to test the efficacy of the “innovations” they fund. “They have the power to change policy, but no corresponding check on that power,” Megan Tompkins-Stange, an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Michigan, told the Times. “It does subvert the democratic process.” School district control doesn’t necessarily guarantee that officials will rigorously oversee large donations.

But if I Promise sticks close to the community school model, and Akron school officials apply the same level of oversight they’d apply to any other public school, the school could be a boon to struggling students. Community schools, which partner with non-profits, churches, and local agencies, often provide health care and adult literacy services in addition to traditional academic offerings. While charter schools can operate a community school model, as the Harlem Children Zone’s charters try to do, the Coalition for Community Schools says on its website that most community schools are public. New York City currently operates 215 community schools, and it isn’t alone. There are publicly run community schools in Oakland, Chicago, and Boston. And though the specifics of the community school model vary from school system to school system, there is a consistent emphasis on providing additional social services for students and parents.

“Just looking at what is online and what’s been reported in the press so far, it is striking how simple it is to build a school like I Promise, at least on paper, and it’s a little startling that we don’t have more,” said Donna Harris-Aikens, who directs the education policy and practice department at the National Education Association. Harris-Aikens credited James and his foundation for beginning first with programming—the I Promise network provides mentorship and extracurricular opportunities for Akron children—before trying to start a school.

Speaking of the traits I Promise shares with community schools, Harris-Aikens added, “I think one of the things that becomes very clear, and not just with community schools but with any strategy that supports public schools, is that it’s about the kids. Start with what the kids have and what the school can do as a part of that community to make sure that they graduate ready for the next stage of their lives. It can be done. It’s a proven model in schools.”

There is some evidence to support the community school model. A 2017 brief produced by the Learning Policy Institute and the National Education Policy Center attributed positive results to schools that incorporate what analysts called the “four pillars” of the model: wraparound social services, expanded learning time, family engagement, and collaborative efforts with community institutions. “By the third and fourth years, students at fully implemented community schools scored significantly higher than their peers in other schools on standardized math and reading tests,” analysts said of the Tulsa Area Community Schools Initiative in the Oklahoma city.

A 2016 Brookings paper asserted that while there are benefits to the community school model, community schools tend to face significant challenges when the services they provide intersect with other sites of social inequality. School funding still often depends on zip code, which reinforces inequality. Community schools can struggle to fund their services over time. Most public schools don’t have celebrity athletes committed to their welfare after all, and the pitfalls of Silicon Valley’s educational philanthropy show that wealthy patrons aren’t always a net benefit to schools in any case. If I Promise succeeds, James won’t just show why schools should be community centers; he may convince public-education skeptics that if you want good schools, you have to pay for them.

No comments :

Post a Comment