F-Secure discovered a cold boot attack that bypasses existing safeguards to let attackers steal information from a laptop's RAM when it's improperly rebooted.

F-Secure discovered a cold boot attack that bypasses existing safeguards to let attackers steal information from a laptop's RAM when it's improperly rebooted.

Before he left for North Carolina on Wednesday to survey damage caused by Hurricane Florence, President Donald Trump released a video celebrating his administration’s response. “This was tough hurricane,” he said, “one of the wettest we’ve ever seen, from the standpoint of water.” The sentiment, though redundant, was technically correct. Florence was the rainiest hurricane on record for the Carolinas, and the eighth-rainiest to ever hit the contiguous United States.

But North and South Carolinians may take issue with Trump’s idea that Florence was a tough hurricane—past tense. Yes, the storm has since dissipated and moved out into the Atlantic. But thousands are still in immediate danger due to flooding caused by overflowing rivers, some of which have yet to reach their highest point. For those people, Florence is a tough hurricane—an ongoing disaster that’s may only get tougher in the coming days. Rivers were still rising in North Carolina on Tuesday, and in South Carolina are expected to continue rising throughout the week.

You can clearly see the water levels rising in Cape Fear River as we compare photos from Sunday to Today. #capefear #Florence #ReadyNC #ReadyFay pic.twitter.com/jiPUCVpLBP

— Fayetteville Police (@FayettevillePD) September 18, 2018Trump’s remarks weren’t the first time a technically accurate statement has failed to relay Hurricane Florence’s particular dangers. Miscommunication about the storm abounded. As Florence approached the Carolina coastline, forecasters noted it had weakened from a Category 4 to a Category 1 storm. This prompted many people to cancel their evacuation plans. “[We] didn’t think it was actually going to be as bad,” North Carolina corrections officer Famous Roberts told the Associated Press. They were wrong.

But they weren’t wrong because the forecasters were wrong. They were wrong because the Saffir-Simpson scale, as the hurricane ranking system is known, only measures hurricane danger in terms of wind speed; it doesn’t take excessive rainfall, storm surge, or the potential for river overflows into account. Americans react accordingly. When preparing for a hurricane, we expect a one- or two-day impact of wind damage, and perhaps some rain and storm surge, before it eventually passes. We don’t expect slow-moving rainstorms like Florence that overflow inland river systems.

The reality is that wind and storm surge are only one part of a hurricane—what University of Georgia meteorologist Marshall Shepherd has called “Phase A.” In a piece for Forbes last week, he argued there’s a lack of public understanding around “Phase B,” the “slow-moving to stalled weakened storm with a lot of rainfall.” Florence has had a particularly dangerous Phase B. So did Hurricane Harvey, which tortured Houston, Texas, with slow-moving rainfall and life-threatening flooding last year.

#Florence is a "Category 5 flood threat," @weatherchannel smartly says. The rainfall forecast remains astronomical. More: https://t.co/4lRd16vBoS pic.twitter.com/RIN0Wt3ExR

— Capital Weather Gang (@capitalweather) September 13, 2018It’s essential that the public be aware of Phase B because such extreme rainfall is becoming more likely. “For every degree Celsius of [global] warming, water vapor in the atmosphere increases by 7 percent,” said Kate Marvel, a climate scientist at Columbia University and NASA. “We’re as sure that climate change means rainier storms as we are that smoking causes cancer.” Phase B is also arguably the more deadly part of a hurricane. According to one major study, only 11 percent of hurricane fatalities are due to wind or embedded tornadoes. The rest are caused by water: ocean storm surge and high surf, for instance, but more importantly inland flooding, which accounts for 55 percent of all deaths.

Some solution-oriented discussion has already begun, such as changing or replacing the Saffir-Simpson scale. “It should definitely be modified to have some factors, including not only wind, but also flooding and maximum storm surge height, or amount of rainfall,” said Irwin Redlener, the director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness. Others aren’t convinced. “[The scale] provides value on the information it as intended for and is useful for historical context or scientific studies,” Shepherd wrote.

Instead, Shepherd suggested forecasters be more frank about the limitations of the Saffir-Simpson scale. “Meteorologists must continue to hammer home the message that inherent dangers of hurricanes like Florence are not completely captured by the scale,” he said. “A simple reminder that Hurricane Sandy was not really even a Category 1 storm when it devastated the northeast United States usually gives people perspective.” The public also has to start listening, he said; many forecasters have been talking about these limitations for years.

But solving the miscommunication problem posed by Florence may require something bigger than changing one meteorological tool. It could require changing how to refer to slow-moving, rain-heavy hurricanes in the first place. Redlener suggested “water disaster.” But whatever the solution, he said, “There are significant reasons to start rethinking how we understand the consequences of large natural disasters.” The main reason being that more are on the way.

For the second time in almost 30 years, the Senate Judiciary Committee is publicly weighing sexual-misconduct claims made against a Supreme Court nominee. Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley announced on Monday that the committee he chairs will hear testimony from both Brett Kavanaugh, a federal appellate judge in D.C., and Christine Blasey Ford, a psychology professor in California who says he sexually assaulted her at a house party during high school in the early 1980s.

Many women have stories similar to Blasey’s, but only one knows what she is currently going through. Anita Hill faced a similar gauntlet in 1991 when she told the committee that Clarence Thomas, her former boss and a pending Supreme Court nominee, had sexually harassed her on multiple occasions. He denied any allegations of wrongdoing and was narrowly confirmed to the court. He serves there to this day.

In a New York Times op-ed on Tuesday, Hill offered some advice to senators as they prepare for next Monday’s hearing. She recommended that senators avoid “pitting the public interest in confronting sexual harassment against the need for a fair confirmation hearing.” She urged them to respect Blasey by referring to her by name instead of vague references like “Judge Kavanaugh’s accuser,” and to appoint a neutral, experienced investigative body to weigh the allegations on the committee’s behalf. She also emphasized that the committee should proceed cautiously, since haste would “signal that sexual assault accusations are not important.”

“A fair, neutral and well-thought-out course is the only way to approach Dr. Blasey and Judge Kavanaugh’s upcoming testimony,” Hill wrote. “The details of what that process would look like should be guided by experts who have devoted their careers to understanding sexual violence. The job of the Senate Judiciary Committee is to serve as fact-finders, to better serve the American public, and the weight of the government should not be used to destroy the lives of witnesses who are called to testify.”

This is a task that may be beyond the committee’s capacity. Some key senators have already expressed doubt about Blasey’s account and questioned its relevance. Utah’s Orrin Hatch told a reporter that even if she was telling the truth, “I think it would be hard for senators not to consider who he is today.” Grassley told reporters, “We’re talking about—you understand we’re talking about 35 years ago. I’d hate to ask—have somebody ask me what I did 35 years ago.” South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham likened the revelation to “a drive-by shooting” against Kavanaugh. “I’ll listen to the lady, but we’re going to bring this to a close,” he added.

That mood pervaded Republicans’ response this week. On Tuesday night, Blasey’s legal representative sent a letter to the committee asking lawmakers to delay the hearing until the FBI conducts an investigation into her allegation. “A full investigation by law enforcement officials will ensure that the crucial facts and witnesses in this matter are assessed in a non-partisan manner, and that the committee is fully informed before conducting any hearing or making any decision,” the letter said. Grassley responded to the letter by not really responding to it at all, pointedly noting in a statement that her invitation to appear before the committee on Monday still stands.

It may be tempting to turn to another institution in American society that could properly weigh the situation. But one of the persistent lessons of the past year is that no such institution exists. The rot runs deep in American society: in movie studios and in media empires, in television networks and major publications, in churches large and small, in courthouses and statehouses, in prosecutors’ offices and prisons, in the military, and universities, and Olympic teams, and Congress, and the White House. If there is a nerve center in American society where persistent, gendered abuses of power have not been found, it may only be because nobody’s thoroughly scrutinized it.

The inescapable conclusion is that the #MeToo movement represents, in practical terms, a crisis for the American rule of law. Countless women and some men have come forward over the past year to describe what are essentially criminal acts committed against them. With rare exceptions, there are typically no formal indictments against those they name, no prosecutions or trials, no verdicts or sentences. Organized society hinges on the premise that there can be restitution for harms done and consequences for those who inflicted them. The consequences felt by those swept up in the Weinstein effect, however, often appear to be rare and fleeting. (Weinstein himself is among the few facing criminal charges.)

Even those who endure workplace sexual harassment and other misdeeds that aren’t quite criminal sometimes have little recourse. Human-resource departments have the paradoxical responsibility of both protecting workers and limiting their company’s legal liability, and the latter often triumphs over the former. The Supreme Court dealt workers a harsh blow earlier this year in Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, upholding the use of forced-arbitration clauses in employment contracts to foil class-action lawsuits like those used to challenge systemic sexual harassment. The impact is felt at all levels of the workforce: Hundreds of McDonald’s workers went on strike this week to protest the company’s failure to address harassment in its franchises.

It’s hard to imagine that an epidemic of arsons or car thefts or letter bombs would be treated like this. And it’s no great leap to conclude that a breakdown in a society’s response leads to a loss of confidence in the public institutions that are supposed to support them. Look no further than the relationship between residents of major cities and police departments that fail to solve large numbers of homicides. “If these cases go unsolved, it has the potential to send the message to our community that we don’t care,” an Oakland police captain told The Washington Post earlier this year.

We are already seeing similar signs. Last week, when Blasey’s accusations were known but her identity was not, Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick noted that it was unsurprising that she wanted to remain anonymous. “I would have told her that neither politics nor journalism are institutions that can evaluate and adjudicate facts about systems in which powerful men use their power to harm women,” Lithwick wrote. “I would have told her that she would be risking considerable peril to her personal reputation, even as she would be lauded as a hero. I would have also told her that powerful men have about a three-month rehabilitation period through which they must live, after which they can be swept up once again in the slipstream of their own fame and success.”

This is what makes the allegations against Kavanaugh so resonant: the idea, perhaps a naive one, that the Supreme Court is supposed to be different. The justices, at least in the ideal, are supposed to represent the American rule of law. The president controls the bureaucracy and the military; Congress controls the budget and impeachment. All that the high court can draw upon is the public’s faith in its integrity. And now the Senate faces the question of whether or not to elevate a new justice whose alleged behavior represents that rule of law’s negation.

Will senators be able to properly weigh this? So far, it’s doubtful. Kavanaugh’s confirmation would markedly shift the court’s ideological balance to the right. As a result, the GOP has generally shown more interest in placing him on the court than in properly vetting his record, even before he was accused of sexual assault. Democrats have performed little better. Kavanaugh’s evasiveness during the hearing never quite reached the threshold of committing perjury, despite their claims. And Democratic senators squandered some of their credibility with insinuations that he discussed the Russia investigation with a Trump-linked legal firm or racked up gambling debts in New Jersey that ultimately went unproven.

Those failings have no bearing on the veracity of Blasey’s story, of course. The would-be justice has consistently denied that anything happened between him and Blasey. “This is a completely false allegation,” he said in a statement on Monday. “I have never done anything like what the accuser describes—to her or to anyone. Because this never happened, I had no idea who was making this accusation until she identified herself yesterday.” Kavanaugh even reportedly suggested in private conversations with Republican senators that it may be a case of mistaken identity.

Some of his defenders, however, are still going out of their way not only to dispute the allegations, but to minimize their significance if they are true. Conservative legal activist Carrie Severino suggested on CNN that what Blasey described was a range of acts that stretched “from boorishness to rough horseplay to actual attempted rape.” Writer Rod Dreher opined that Kavanaugh’s “loutish drunken behavior” offered no insights into his current character, adding that it was a “terrible standard to establish in public life.” Bari Weiss, a New York Times opinion editor, said in an MSNBC interview that she believed Blasey, but added, “By all accounts, other than this instance, Brett Kavanaugh has a reputation as being a prince of a man, frankly, other than this.”

It looks like the Senate Judiciary Committee’s flaws aren’t unique to it after all. Maybe that means it’s not necessarily the committee, or any other institution, that’s truly the problem. Maybe it’s just the people and the culture that occupy it.

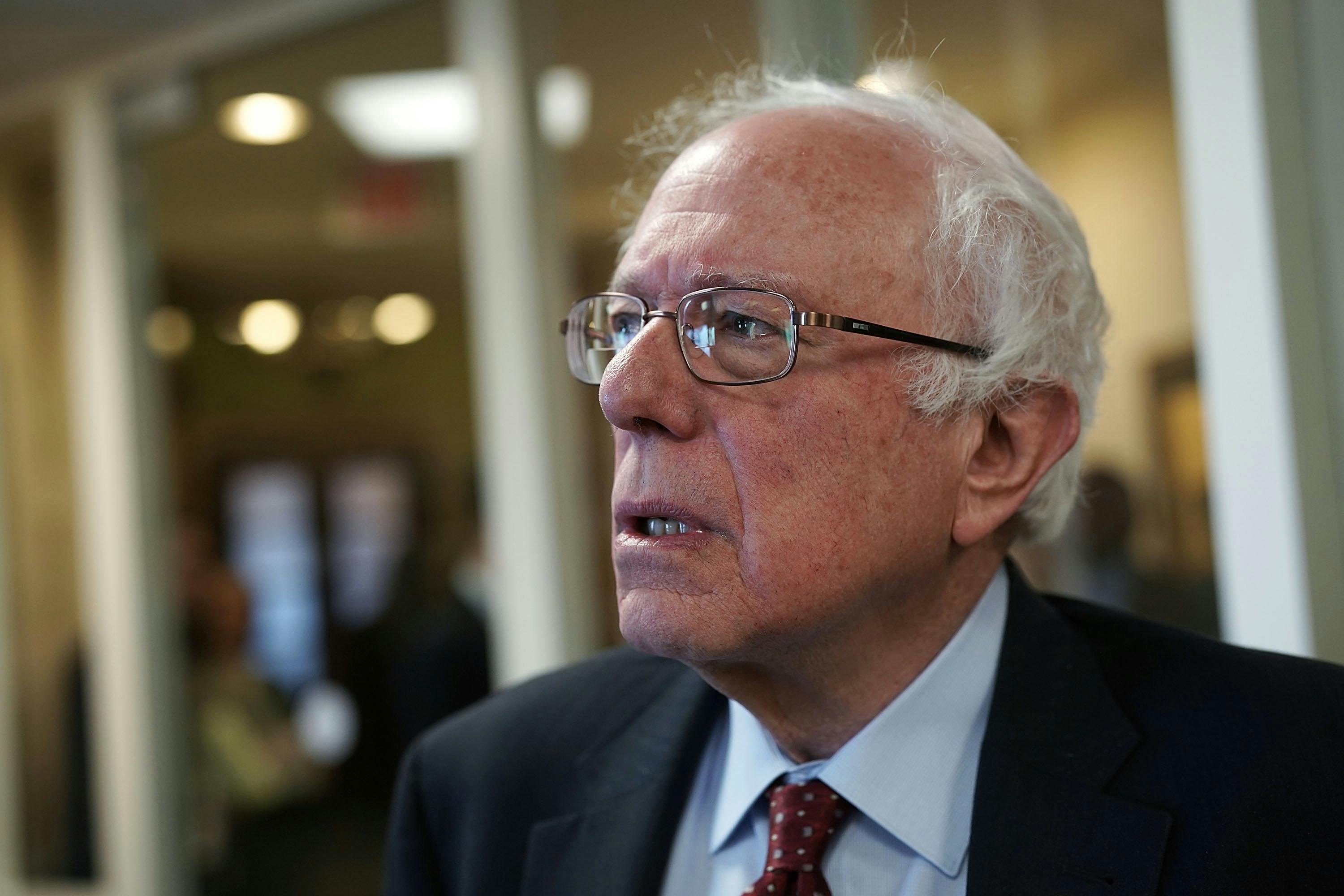

Senator Bernie Sanders has spent much of the summer highlighting the low wages at major American corporations and contrasting it with the astronomical pay for top executives. The title of a town hall in July made his point clear: “CEOs vs. Workers.” (The workers showed up; the CEOs didn’t.) A petition he launched in August targeted Amazon specifically, noting that CEO Jeff Bezos makes “more money in ten seconds than the median employee of Amazon makes in an entire year” and arguing that “thousands of Amazon employees are forced to rely on food stamps, Medicaid and public housing because their wages are too low.”

This assistance amounts to a form of “corporate welfare,” Sanders argued, and earlier this month he and California Representative Ro Khanna introduced a bill that aims to curtail it. The Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies Act (Stop BEZOS) would require companies with 500 or more workers to reimburse the government for the cost of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, school lunch, and Section 8 benefits claimed by their employees. The bill received predictable pushback from the employers targeted, but it also was criticized by a variety of experts on the left.

Stop BEZOS, progressive wonks argued, not only stigmatized programs like SNAP, but misunderstood how those programs work. Because these benefits aren’t predicated on work, they aid low-wage workers, not low-wage employers. The only thing Stop BEZOS might accomplish, critics said, is incentivizing employers like Amazon to avoid hiring workers, such as single parents, that are likely to be eligible for public assistance. The bill’s proponents didn’t take the criticism lightly. Sanders’s policy director, Warren Gunnels, created a stir when he claimed that one of the plan’s critics, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), was motivated by its receipt of donations from the Walmart Foundation.

Sanders and Khanna are right that parts of the threadbare U.S. safety net act as a form of corporate welfare, but they singled out the wrong parts. If progressive legislators and wonks are serious about making sure that public assistance intended for the poor doesn’t flow to companies like Amazon and their billionaire owners, they need to fix the Earned Income Tax Credit and challenge the conservative “pro-work” philosophy that underpins it.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which was claimed by 27 million workers and families last year, is a refundable tax credit that’s tied to a worker’s earnings. Starting with the first dollar of earned income, the EITC gradually phases in, growing larger with each additional dollar of earned income until it reaches a maximum amount. Workers who don’t earn the full phase-in income—currently about $10,000 for a worker with one child—don’t get the full EITC credit. The EITC also phases out as a worker earns more than the full-credit income. At that point, each dollar of earned income gradually reduces the value of the EITC until it reaches zero.

In its four-decade history, the EITC has enjoyed enviable bipartisan support. It’s been expanded by Democratic and Republican presidents alike, growing dramatically in both the size of the credit and total cost of the program, and ultimately assuming the role of the largest anti-poverty program for the non-aged. Democrats and liberal think tanks have put forward an endless array of proposals to expand it—something that both Khanna and the CBPP, despite taking opposite stances on Stop BEZOS, have championed. Meanwhile, Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan called the EITC “one of the federal government’s most effective anti-poverty programs” and put forward his own expansion proposal.

The EITC has flourished despite—or perhaps because of—the racist and anti-poor assumptions that animated its creation. By the mid-1960s, both liberals in the Lyndon Johnson administration and conservatives like Milton Friedman had coalesced around the idea of replacing the complex, paternalistic system of cash welfare then known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) with a “negative income tax” (NIT) that would level up every poor person to a basic income amount, regardless of whether they worked, then phase out gradually as work income replaced NIT dollars. President Richard Nixon embraced a moderate version of the idea with his Family Assistance Plan (FAP), while progressive activists in the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) pushed liberal Democrats to back their more generous proposal. Ultimately, Senator George McGovern made a $1,000 “demogrant” that would have gone to every American regardless of income or work—thereby making it more of a “universal basic income” (UBI) than an NIT—central to his 1972 presidential campaign.

For conservative Republicans, none of these proposals was acceptable. But as chair of the Senate Finance Committee, conservative Louisiana Democrat Russell Long led the charge in killing any variant of an NIT/UBI. While Long had no problem defending various forms of corporate preferences embedded in the tax code, he had deep antipathy for the non-working poor. He allegedly referred to the NRWO—which featured many African American mothers in its leadership—as “Black Brood Mares, Inc.” and slammed NIT/UBI proposals as plans to “reward idleness and discourage personal initiative” by “paying people not to work” and “lay about all day making love and producing illegitimate babies.” Instead of giving the poor (or every American) money regardless of whether they worked, Long proposed a “work bonus” tied to employment. This “work bonus” ultimately became the EITC, which President Gerald Ford signed into law as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975.

Long’s work-conditional vision captured the shift to the right on welfare taking place in both parties. Ronald Reagan, who’d strenuously opposed FAP, filled the void in the GOP left by Nixon in the wake of Watergate, while moderate Democrats like Bill Clinton assumed power in the Democratic Party in the wake of McGovern’s defeat. Reagan famously demonized a “welfare queen” in his failed 1976 campaign for president, and as president he pushed cuts to a variety of safety net programs in order to combat what he called “welfare culture.” Clinton ran for president in 1992 as an unabashedly anti-welfare, pro-work Democrat, pledging to “end welfare as we know it” by forcing the poor off of the welfare rolls and into the workplace.

Conservatives (and some liberals) are fond of quoting liberal economist Arthur Okun’s likening of income redistribution to a “leaky bucket.” According to Okun, both administrative costs and foregone economic growth mean that if the government takes a dollar from the rich, it won’t necessarily be able to give that entire dollar to the poor. While the size of the leak is hotly debated—and despite the fact that Okun argued that we should be willing to tolerate significant leaks for the sake of greater equality—the leaky bucket has become a staple of Econ 101 as a representation of the unintended consequences and inherent “inefficiency” of social welfare programs.

But programs like the EITC are the leaky bucket we should really worry about. Because the credit is conditioned on work, it expands the supply of available labor and increases the power of employers relative to workers. The program thus drives wages down to the extent that a dollar spent on EITC only raises worker wages by around 70 cents, while employers keep the rest, according to research by economist Jesse Rothstein. (Other scholars have reached similar conclusions.) So a substantial chunk of the $60-plus billion spent on the EITC every year really is the type of “corporate welfare” that Sanders rightly decries.

The “end of welfare” has had a predictably deleterious impact on the most vulnerable, pushing them into deep poverty, and tying assistance to work has placed programs like the EITC out of reach for the (disproportionately black and Latino) Americans who can’t find work. The U.S. simply can’t afford to let nearly a third of its largest non-elderly anti-poverty program “leak” back to companies like Amazon and Walmart. If Sanders and Khanna want to rid the safety net of hidden corporate welfare, they’d do well to propose ending the EITC’s work requirements and turning it into an NIT, providing every poor person with a basic income regardless of work. According to Rothstein’s estimates, an NIT would have the opposite effect of the EITC. An NIT would increase workers’ bargaining power, thereby increasing wages for those at the bottom by $1.39 for every dollar spent.

But making a full-throated case for the NIT will require Sanders, Khanna, and other left-wing lawmakers to stop equating work with deservingness—an association that “job guarantee” proposals, and mantras like “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty” inadvertently deepen. It will also require letting go of the myth that Republicans will accede to social programs tied to work. There’s a reason that Paul Ryan’s modest expansion of the EITC went nowhere. The GOP’s support for the EITC has always been exaggerated, and Republicans recently have attacked the EITC over (virtually nonexistent) fraud. For Republicans, work requirements are merely the precursor or second-best alternative to outright cuts.

At the very least, Democrats should move the EITC towards a de-facto NIT by setting the phase-in of the full credit to as low an income as possible. While the prospect of the non-working poor declaring phantom “earned income” to qualify for the EITC is an absurd exercise in tax chicanery, it’s certainly no worse than what many rich Americans get away with every year, and it’s significantly better than the status quo, where employers capture a substantial portion of the EITC and the non-working poor get nothing.

When protests inspired by uprisings in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia hit Yemen in 2011, the United States and the United Kingdom, the regime’s main backers, at first pooh-poohed the protestors’ grievances. Only after anger over the endemic corruption and the economy split Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s regime in two, sparking street battles between regime loyalists and Sunni military and tribal fighters, did Yemen’s foreign partners start to worry. Fearing Somalia-like chaos that would be exploited by the local Al Qaeda franchise, they brokered a deal for Saleh to step down.

Three years later, Western diplomats were celebrating the success of their “Yemen model” for dealing with political upheaval and suggesting it might work in Syria and Libya. But trouble was brewing. Despite a new president, the basis for a new constitution, and a genuinely impressive nine-month “national dialogue conference” attended by most major Yemeni factions including civil society groups, buy-in to the new-model Yemen—which looked an awful lot like the Yemen of old—was deceptively low.

In July 2014, the entire post-Arab Spring arrangement broke down when the government tried to slash fuel subsidies, nearly doubling the price of fuel at the pump. The Zaydi Shia Houthi rebels accused the president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, and his government of corruption and fecklessness. By the end of September, after several days of fighting, the Houthis controlled the city—something that had seemed impossible just a few months earlier. By the following spring, the civil war had begun in earnest. Saudi Arabia, viewing the Shia Houthis as a proxy for Iran, added heavy aerial bombardment to the mix.

Four years on from the hype of the “Yemen model,” Yemen is mired in a devastating civil war that has triggered the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Conservative estimates are that 10,000 civilians have died, although the total is likely much closer to 50,000. Upwards of 20 million need some kind of humanitarian assistance. A million people have been infected with cholera. And no end is in sight.

Often simplified into a proxy battle between Iran and Saudi Arabia, in reality the war has devolved into multiple, overlapping conflicts driven by an ever-changing patchwork of rivalry and alliance. Salafists and secessionists backed by the United Arab Emirates often expend as much energy battling their nominal allies, Saudi Arabia-funded Islamists and loyalists of the internationally recognized President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, as they do the Houthis. The local franchises of Al Qaeda and the Islamic State publish videos from the frontlines of battles against the Houthis in areas the government claims is under its control. A common thread runs through each of these internecine struggles: the desire—or the demand—for legitimacy.

I lived and worked in Yemen during the transitional period following Saleh’s ouster in 2011. Beyond the headlines, what I found was a country in the midst of a slow-motion collapse. It didn’t matter whether you were talking to Sunni Islamists or Zaydi Shia Houthis, southern secessionists or frustrated technocrats: Yemen was plagued with fuel and job shortages. The cost of living was soaring as incomes fell to zero. The government was unable to provide security and the judicial system, broken as it was before, had collapsed. The new “unity” government—made up of rival factions from the old regime—was paralyzed by infighting. Few Yemenis outside of the big cities knew or cared much about the political transition or dialogue process. They were too busy trying to eke out a living. For many, the main symbol of international intervention in Yemen was a regular succession of U.S. drone strikes that all too often killed innocent people rather than Al Qaeda militants. Unsurprisingly, secessionist sentiment was growing in the South while the Houthi rebels in the North were both making gains on the ground, and marketing themselves as a meaningful alternative to the old elite—as in fact was Al Qaeda. The legitimacy of the political order in Sana’a was in crisis, sparking a free-for-all.

Legitimacy, according to New Zealand political scientist Kevin Clements, “is about social, economic and political rights, and it is what transforms coercive capacity and personal influence into durable political authority.” It’s about “whether the contractual relationship between the state and citizens is working effectively or not.”

In the first decade of the 2000s, the political economist Sue

Unsworth proposed a way of testing the overall legitimacy of the political

order that underpins a state by asking four questions:

1. Does the political system comply with the agreed-upon rules of procedure (the constitution and the law) in the country in question?

2. Does the state provide basic public goods (like healthcare, education, security and a legal system)?

3. Is there a shared vision for the country among the ruling class and the ruled?

4. Is there international recognition for the political order?

If you’re a diplomat or a local government official you are likely to think rules and recognition are the priority. But if you’re a normal person going to work or trying to find work, shopping for food, and bringing up a family, the services and a shared vision are likely the most important. And the worse conditions are, and the less likely they seem to change, the more appealing the idea of overturning the status quo becomes.

For this reason, there is a simpler test for the legitimacy of a state, which is to ask whether the current setup is good enough that the population at large doesn’t feel the need to agitate for major change. If people take to the streets in huge numbers demanding the fall of the regime, even if the regime responds with violence – as happened across the Arab world in 2011—that’s generally a sign that the system is failing the test. From 2011 onwards, Yemen scored a pretty consistent F.

Western officials I spoke to in Sana’a between 2012 and 2014 recognized that the economy, the failure of basic services like electricity and water, and rule of law were big issues. But they were struggling to strike a balance between directives from their own capitals largely focused on counterterrorism, maintaining the fragile détente between Saleh supporters and their elite rivals, and keeping an increasingly vulnerable president Hadi grounded. Because they and their Yemeni counterparts were focused on Sana’a politics, that’s what they perceived as ultimate priority.

You’d hope that people would learn from past mistakes. But since a Saudi-led coalition entered the war in March 2015 with the stated aim of restoring Hadi, who fled the Houthi-controlled capital earlier that year, little effort has been made to restore the state’s perceived legitimacy in areas ostensibly controlled by Hadi’s government (which likes to call itself al-shareia, or “the legitimacy”).

Al Qaeda seems to have been the group that thought hardest about legitimacy.Most officials work from Riyadh, with the prime minister and a select few officials cloistered in the presidential palace in Aden. Yemen’s southernmost provinces were liberated from the Houthi-Saleh alliance in 2015 by local forces but lack basic services like electricity and water. The South remains deeply insecure. Forces loyal to Hadi clash regularly with UAE-backed secessionist militias. The security picture is better in Mareb, in central Yemen, where the Houthis were also largely ejected in in 2015. The province now exists as a largely autonomous region, run by the Governor Sultan al-Aradah, with little input from Hadi.

The Houthis aren’t doing any better: deeply unpopular in the territories they control in the highlands and the west coast, they rule largely through a mixture of fear and bribery. And for many Yemenis, the international community isn’t all that legitimate either.

In stark contrast to these slap-dash approaches, Al Qaeda seems to have been the group that thought hardest about legitimacy: When it took over the southern port city of Mukalla in 2015, it focused on service delivery and running its own local courts, with some success. This was part of a carefully-wrought strategy from then-Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) emir Nasir al-Wuhayshi, which can be seen emerging in letters to fellow Al Qaeda leaders in previous years. When Cyclone Chapala battered Southern Yemen in November 2015, AQAP-ruled Mukalla was best prepared for the deluge, evacuating residents from their homes and ensuring a steady supply of bottled water was available. (The group also filmed its work in Mukalla obsessively and heavily promoted videos of life in Mukalla that presented a softer vision of its mission than the then-ascendant Islamic State.) In April 2016, the group was forced out of the city by local UAE-backed forces.

The fact is, no one in Yemen is consistently perceived as legitimate across all cross-sections of society. And Al Qaeda and Marebi sheikhs aside, no one seems to be all of that interested in earning their legitimacy.

Why does this matter? Earlier this month, the new U.N. special envoy to Yemen, Martin Griffiths, tried to get Hadi and the Houthis to sign up to his framework for a peace process during meetings in Geneva. The Houthis ultimately failed to show, but Griffiths’s plan—which remains unchanged—is a familiar one: form a unity government and start a new period of political transition, and then bring other groups in later.

It makes sense that Griffiths wants to simplify peace talks for now. But the danger is that Griffiths’s backers—the member states of the U.N. Security Council, the Gulf states and others—will fall back into the same old patterns: They will quietly help install some familiar faces in government, look for technical solutions and bold visions for the future that exist only on paper, and react with surprise when a government made up of the elite of 2018 fails to do anything to build legitimacy on the ground and the events of 2011 and 2014 repeat themselves.

Western diplomats and officials have yet to accept that legitimacy is not the same thing as the broad, legal authority that the international community can confer on an individual or group like President Hadi. Nor does legitimacy automatically accrue to a central government, even when an election has been won.

Legitimacy is won at the local level, by listening and engaging with people on the ground, delivering services, and creating buy-in to the wider national system, with all the messiness and complexity that entails. It is won by setting realistic goals, one at a time, and achieving them, not just setting out bold new visions for the future, although these are unquestionably an important part of a longer-term process. Until people are ready to get their priorities straight in Yemen, the country is likely to remain deeply unstable.

No comments :

Post a Comment