Since the sexual assault allegations against him were made public earlier this month, can you think of a single thing Brett Kavanaugh has done or said that makes you more confident that he’ll be a judge of high integrity on the Supreme Court? I cannot. At every step of the way he has acted less like a potential justice and more like a partisan functionary, desperately clinging to the chance at the job of his lifetime. He has, in this way if not others, already disqualified himself for the job regardless of how the (now two) sexual assault allegations against him pan out.

There are Christine Blasey Ford’s credible allegations of “attempted rape” that Kavanaugh must answer for during a hearing scheduled for Thursday before the Senate Judiciary Committee. And now there are new allegations that Kavanaugh engaged in sexual misconduct not just in high school, when Ford says the episode took place, but also at Yale University, where Kavanaugh attended. A woman named Deborah Ramirez has stepped forward to tell Ronan Farrow and Jane Mayer at The New Yorker that Kavanaugh thrust his penis in her face at a drunken party in the 1983-84 school year and made her touch it.

Kavanaugh denies the new allegation with the same vigor with which he has denied Ford’s allegations. But the emergence of Ramirez makes it even more imperative that Republicans on the Judiciary Committee stop the voting track and investigate all of this in a serious way. That means they must abandon the he-said/she-said plan for Thursday’s hearing and open it up to other witnesses who will either incriminate or exculpate Kavanaugh and the women who say he’s a sex offender. And it means Kavanaugh and the White House must abandon the approach they’ve taken to his defense so far.

Kavanaugh is not on trial for his life. He’s not a defendant in a court of law. His accusers and their supporters need not make a case of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. They don’t even need to make a case using the civil standard of a “preponderance of the evidence.” This notion that Kavanaugh can convince America that he is innocent by producing his calendar from 1982 is patently absurd in a process in which live witnesses are barred from providing their insight about what Kavanaugh’s life was like in those days. It wasn’t going to fly when Ford was the only accuser. It’s certainly not going to fly now that Ramirez has stepped forward.

But put aside these other people and focus only on the man who wants to help shape the course of American law for the next two generations. The man who preached “judicial independence” during his listless testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee earlier this month, the man who is a life-tenured judge on a federal appeals court, spent parts of at least four days last week at the White House being “prepped” for his looming confrontation with Ford. Prepped, that is, by the very executive branch officials whose presidential privilege claims he may be asked to adjudicate, in a matter of months perhaps, if he ascends to the High Court. That’s not judicial independence. That’s a conflict of interest.

The nominee became “incredibly frustrated,” we are told, about all the questions he now has to answer about his drinking habits and sex life as a teenager. The pious preacher of integrity and honor during his confirmation hearing would rather get the job without having to tell the American people what sort of teenager he was. That attitude—the antithesis of selfless public service, an anti-judge perspective, a good-old-boys thing—was summed up on a Sunday talk show. “What am I supposed to do?” wailed Senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the committee. “Go ahead and ruin this guy’s life based on an accusation?”

No. What Graham and his Senate colleagues are supposed to do is take the Ford and Ramirez allegations seriously and do everything possible to ensure a full and fair investigation takes place before there is a vote on Kavanaugh’s nomination. What they are supposed to do is realize that going public with the allegations already has “ruined” Ford’s life, a reality about sexual abuse she understood for all those long years in which she remained silent. Indeed, what’s persistently missing from the Republican defenses of Kavanaugh is the extent to which Ford and Ramirez already have laid it all on the line.

And Kavanaugh? What he’s supposed to do is everything he has not done so far. He’s supposed to say that it is more important to him to get to the heart of the matter, wherever it leads, than it is for him to get promoted to the Supreme Court. He’s supposed to say that he will withdraw his name from consideration for the job if the Senate is unable or unwilling to adequately investigate the Ford and Ramirez claims. He is supposed to put his country above his own personal and professional goals. If he is as innocent as he and his defenders claim he is, this is the only “honorable” approach out of this mess.

I keep going back to all that prep work and Kavanaugh’s reaction to it. Kavanaugh is no ordinary witness, this is no ordinary testimony, and so what is there to prep for, exactly, if Kavanaugh is as innocent as he claims? What kind of “lawyering up” does lawyer Kavanaugh need if he were not at that long-ago party where Ford alleges she was almost raped? Or the other party where Ramirez says Kavanaugh imposed himself on her? The nominee is no novice when it comes to courts and courtrooms. He doesn’t need a lesson, or a reminder, in how a witness should or should not act. He has to be both persuasive and honorable, writes Benjamin Wittes, but if that is true then it’s either genuine, in which case Kavanaugh needs no coaching, or it is not, in which case Kavanaugh is worse than dishonorable.

The truth is that Kavanaugh is being coached in great detail to clap together precisely the right phrases during his next round of public testimony that will allow Vichy Republicans like Susan Collins or Jeff Flake to declare themselves satisfied that he’s not an attempted rapist. He’s also being coached on what to say more broadly about sexual assault and victimization so as not to further erode Republican support among women this election season. There is nothing about any of this that enhances anyone’s argument that Kavanaugh has a judicial temperament that warrants his inclusion on the Supreme Court.

As if Kavanaugh’s collusion with the White House in advance of his Senate testimony isn’t worrisome enough, there also now is the question of the connection, if any, between Kavanaugh and Ed Whelan, the conservative ideologue who pitched a dubious “mistaken identity” theory last week in which he named another man as Ford’s possible abuser. Did Kavanaugh and White House operatives know that Whelan was going to pitch this conspiracy theory dreck? Would it surprise anyone that Bill Shine, the former Fox News executive now at the White House, would pull a stunt like that? And what happens now that Ramirez has emerged? More strategy sessions between the executive and judicial branches?

I can understand how upset Kavanaugh is, as I wrote last week, being so close to his life’s goal only to have this happen. But that does not excuse the very un-judge like behavior Kavanaugh has exhibited in the past two weeks. He has acted like a guilty man trying to hide something instead of a righteous man knowing the truth will help him past this hurdle. He as acted like a nominee who believes it’s more important to get the job than it is for him to have any respect when he has the job. Even if you didn’t think he was disqualified for the ferocity of his conservative ideology, his reaction to these allegations tell us he’s unworthy of the job for which he is nominated.

You would think there would be more literature about why men are so angry—the president, the mob in Charlottesville a year ago, the alt-right generally, the bar brawlers, the wife-beaters, the gay-bashers, the man who got more famous than he anticipated for screaming at a couple of women who were speaking Spanish in a Manhattan restaurant earlier this year. Add to this all the high-powered, high-profile men—the #MeToo perpetrators—who have been cruel and degrading to women, and the men who went berserk in early August when The New York Times appointed Sarah Jeong to its editorial board, slinging sexualized and racist insults at her because she had dared to criticize them. Anger is often entangled with entitlement—the assumption, which underlies a lot of the violence in the United States, that one’s will should prevail and one’s rights outweigh those of others.

Male anger is a public safety issue, as well as a force in the ugliest politics and social movements of our time, from the epidemic of domestic violence to mass shootings, and from neo-Nazis to incels. Because we normalize the behavior of men—and of white men in particular—the fact that a lot of far-right movements, such as the American neo-Nazi terror group Atomwaffen Division, are mostly male, is seldom noted. (Michael Kimmel’s recent book, Healing From Hate, which examines male fury in global politics, is among the valuable exceptions.) We have until very recently treated it as inevitable that women should adapt to these outbursts with Mace in our purses, self-defense lessons, and limits on our freedom of movement, tiptoeing around men who use their volatility to intimidate and control others.

.tns-outer{padding:0 !important}.tns-outer [hidden]{display:none !important}.tns-outer [aria-controls],.tns-outer [data-action]{cursor:pointer}.tns-slider{-webkit-transition:all 0s;-moz-transition:all 0s;transition:all 0s}.tns-slider>.tns-item{-webkit-box-sizing:border-box;-moz-box-sizing:border-box;box-sizing:border-box}.tns-horizontal.tns-subpixel{white-space:nowrap}.tns-horizontal.tns-subpixel>.tns-item{display:inline-block;vertical-align:top;white-space:normal}.tns-horizontal.tns-no-subpixel:after{content:'';display:table;clear:both}.tns-horizontal.tns-no-subpixel>.tns-item{float:left;margin-right:-100%}.tns-no-calc{position:relative;left:0}.tns-gallery{position:relative;left:0;min-height:1px}.tns-gallery>.tns-item{position:absolute;left:-100%;-webkit-transition:transform 0s, opacity 0s;-moz-transition:transform 0s, opacity 0s;transition:transform 0s, opacity 0s}.tns-gallery>.tns-slide-active{position:relative;left:unset !important}.tns-gallery>.tns-moving{-webkit-transition:all 0.25s;-moz-transition:all 0.25s;transition:all 0.25s}.tns-lazy-img{-webkit-transition:opacity 0.6s;-moz-transition:opacity 0.6s;transition:opacity 0.6s;opacity:0.6}.tns-lazy-img.loaded{opacity:1}.tns-ah{-webkit-transition:height 0s;-moz-transition:height 0s;transition:height 0s}.tns-ovh{overflow:hidden}.tns-visually-hidden{position:absolute;left:-10000em}.tns-transparent{opacity:0;visibility:hidden}.tns-fadeIn{opacity:1;filter:alpha(opacity=100);z-index:0}.tns-normal,.tns-fadeOut{opacity:0;filter:alpha(opacity=0);z-index:-1}.tns-t-subp2{margin:0 auto;width:310px;position:relative;height:10px;overflow:hidden}.tns-t-ct{width:2333.3333333%;width:-webkit-calc(100% * 70 / 3);width:-moz-calc(100% * 70 / 3);width:calc(100% * 70 / 3);position:absolute;right:0}.tns-t-ct:after{content:'';display:table;clear:both}.tns-t-ct>div{width:1.4285714%;width:-webkit-calc(100% / 70);width:-moz-calc(100% / 70);width:calc(100% / 70);height:10px;float:left} .tns-outer button[data-action] { display: none; } .tns-nav button { background: black; border: none; width: 5px; padding: 0; height: 5px; margin: 5px; border-radius: 50%; } .tns-nav button[aria-selected="true"] { opacity: 0.2; } .my-slide { max-width: 400px; }Instead of a theory of male anger, we have a growing literature in essays and now books about female anger, a phenomenon in transition. Rebecca Traister’s new book, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, scrutinizes its causes, its repression, and its release in the last half-dozen years of feminist action, particularly in response to the treatment of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, and in the remarkable power shift that women demanded in #MeToo. Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger focuses on the ways in which women’s (and by contrast, men’s) emotions are managed, judged, and valued in contemporary North American life, while Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower is a first-person narrative about power, solidarity, race, gender, and their intersections.

These books arrive at a moment when a lot of women have changed and too many men have not—and some are, in fact, retreating into revved-up misogyny and rage against the erosion of their supremacy. Women no longer obliged to please men may finally be able to express rage, because we’re less economically dependent on men than ever before, and because feminism has been redefining what’s appropriate and acceptable. “Gender-role expectations . . . dictate the degree to which we can use anger effectively in personal contexts and to participate in civic and political life,” Chemaly notes. “A society that does not respect women’s anger is one that does not respect women—not as human beings, thinkers, knowers, active participants, or citizens.”

The same feminist transformations that have allowed this outpouring may eventually wear down some of the causes of our anger. Much of the anger discussed in all these books comes from being thwarted—from the inability to command respect, equality, control over one’s body and destiny, or from witnessing the oppression of other women. One of the pitfalls in trying to establish equality is to confuse gaining power with unleashing rage. For all of us this is the conundrum: How, without idealizing and entrenching anger, can we grant nonwhite people and nonmale people an equal right to feeling and expressing it?

There’s a zen story I heard long ago, about a samurai who demands that a sage explain heaven and hell to him. The sage replies by asking why he should explain anything to an idiot like the samurai. The latter becomes so enraged in response that he draws his sword and prepares to kill. The sage says as the blade approaches, “That’s hell.” The samurai pauses, and realization begins to flood in. The sage says, “That’s heaven.” It’s a story about anger as misery and ignorance, and awareness as the antithesis.

Verbal rage and physical violence are weaknesses. (Here I think of Jonathan Schell’s book on the power of nonviolence, The Unconquerable World, which makes the case that even state violence is ultimately weakness, since, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. … to speak of nonviolent power is actually redundant.”) Equanimity is one of the key Buddhist virtues, and anger is considered a poison in many Buddhist philosophies. It too often hardens into hate or boils up into violence. The sage makes clear that the samurai feels lousy when he’s about to commit a murder. Angry people are miserable. The sage also shows that the samurai is easily yanked around by what someone else does or says. Easily angered people are manipulable.

We assume, at least about male anger, that it’s an inevitable and normal reaction to unpleasant and insulting things, and that it’s powerful.

Yet here in the West, we talk about anger constantly, and we’re a lot more like the samurai than the sage. We assume, at least about male anger, that it’s an inevitable and normal reaction to unpleasant and insulting things, and that it’s powerful. This summer, NBC broadcast a video of a man from Nashville flying into a rage after he repeatedly propositioned a woman at a gas station and she turned him down. (Did he think women came to gas stations to get dates, not gas and maybe a soda? Or did he just think that women in general owed him, and he had the right to punish any stranger of that gender for disobedience?) In the footage, the man jumps onto the woman’s car, kicks in her windshield, and then assaults her directly. This inability to take no for an answer is far from rare. Since 2014, a Tumblr titled “When Women Refuse” has kept track of “violence inflicted on women who refuse sexual advances.” There is no shortage of examples, some of them fatal.

For those whose anger is sanctioned, its display can net rewards—if you want to be part of a system of intimidation and extortion, if you imagine the people you interact with as primarily competitors to be bullied rather than collaborators to be embraced. Some of the most privileged people on earth are raging and roaring their way through life—notably the president and his older white followers whose faces, scrunched in fury, can be seen at his rallies. These crowds are angry, perhaps because the alternative is to be thoughtful about the unfairness and complexity of this time and place and what they demand of us.

Activists, dressed as Handmaids, protesting restrictionson abortion at the Texas Capitol in Austin in 2017. Eric Gay/AP Photo

Activists, dressed as Handmaids, protesting restrictionson abortion at the Texas Capitol in Austin in 2017. Eric Gay/AP PhotoMuch of what Traister and Chemaly address in their books is a double bind: We live in a world in which there is a good deal for women to object to, including the fact that a lot of men wish to harm and humiliate and subjugate us, but responding to that comes with its own penalties. When a woman shows anger, Chemaly observes, “she automatically violates gender norms. She is met with aversion, perceived as more hostile, irritable, less competent, and unlikable.” But even if, for example, she says quite calmly that gender violence is epidemic, she can still be attacked and characterized as angry, and that anger can be used as a way to discount the evidence, in a society that often still expects that women be pleasing and compliant.

A disturbing anecdote that Chemaly tells shows how early in life women are denied the right to be angry. At her daughter’s preschool, a boy keeps knocking down the towers that her daughter builds while his parents justify his aggression and refuse to prevent it. “They sympathized with my daughter’s frustration but only to the extent that they sincerely hoped she found a way to feel better,” Chemaly writes:

They didn’t seem to “see” that she was angry, nor did they understand that her anger was a demand on their son in direct relation to their own inaction. They were perfectly content to rely on her cooperation in his working through what he wanted to work through, yet they felt no obligation to ask him to do the same.

All three authors point out that race, as well as gender, sorts out whose anger is tolerated and whose is condemned. Among the black women Traister interviewed are Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and Representative Barbara Lee, who tells gripping stories about her own birth—in a hospital that nearly let her mother die because of her color—and about her mentor, congresswoman and 1972 presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm. Chemaly talks about the ways conservatives imagined and impugned Michelle Obama’s anger, and also reflects on her own family’s avoidance of women’s pain and anger. She wonders if it was rage that made her mother break all the best dishes by silently hurling them, if it was rage that her grandmother—kidnapped as a teenager by her grandfather—felt about a life in which she had little say.

Traister’s book documents moments when women have overturned expectations of silence and compliance in order to bring about change. As well as recent events, she presents vignettes from earlier eras of American history, covering Mother Jones, and the Industrial Workers of the World; Fannie Peck, who organized “Housewife Leagues” in Detroit; Rosa Parks and her only recently rediscovered, pre-bus-boycott feminism; the drag queens and transwomen who led the Stonewall Riot but were lost in the legend; and Anita Hill, who faced viciously condescending white men when she testified in Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearing. Traister portrays these women’s motives for standing up in each case as anger, an anger that gave them the energy to do what they did.

Rosa Parks on the day in 1956 when buses in Montgomery, Alabama, were desegregated; Anita Hill traveling to Washington, D.C., to give testimony in 1991.Bettmann/Getty; Doug Mills/AP Photo

Rosa Parks on the day in 1956 when buses in Montgomery, Alabama, were desegregated; Anita Hill traveling to Washington, D.C., to give testimony in 1991.Bettmann/Getty; Doug Mills/AP Photo Yet sometimes it seems that energy might come from something else. Traister quotes Representative Lee saying that in public Chisholm would be “so cool, her voice and demeanor tough and strong and boom, boom, boom,” even when she was upset. “But get her behind closed doors? She’d let her guard down and acknowledge her pain.” Was her pain the same as anger? Or was it something else? Traister also quotes Garza saying that “what is underneath my anger is a deep sadness” and that it breaks her heart “to hear that a woman as visionary as Shirley Chisholm used to cry.” Later, Garza tells Traister that

the question for us is: Are we prepared to try and be the first movement in history that learns how to work through that anger? To not get rid of it, not suppress it, but learn how to get through it together for the sake of what is on the other side?”

What is on the other side is not quite clear, but Garza definitely takes the view of the sage, though she has compassion for the samurai in all of us. Perhaps Cooper is already there. Her book is as much a book about love as it is about anger: self-love and the struggle to find and hold it; love for the many women in her life, as well as public figures from Ida B. Wells to Audre Lorde to Terry McMillan to Hillary Clinton (they all talk about Clinton, of course); and at least implicitly a love of justice, of equality, of righting wrongs and telling truths. It is a warm and generous work, and a fierce one. All three books are compendiums of enormous numbers of anecdotes from and figures on recent American life, but Cooper’s is distinct both for its telling as the author’s own journey and for its—yes—eloquent personal voice, which, between her erudition (she is a professor at Rutgers) and her command of vernacular, is funny, wrenching, pithy, and pointed.

Returning to the fable, it seems the interaction between the two figures is about many less obvious things than fury and restraint. One of those things is power: If the sage had held the sword and the power of life and death with it, it’s easy to imagine his interlocutor would have been less eager to turn to violence, and their interaction would have stopped with the insult. Imagine a woman asked the sage the same question and he told her she was stupid and ineligible for enlightenment. Like the samurai, she might resent it, but, unlike him, she might not express that resentment, because expressing it will just open her up to other kinds of condemnation.

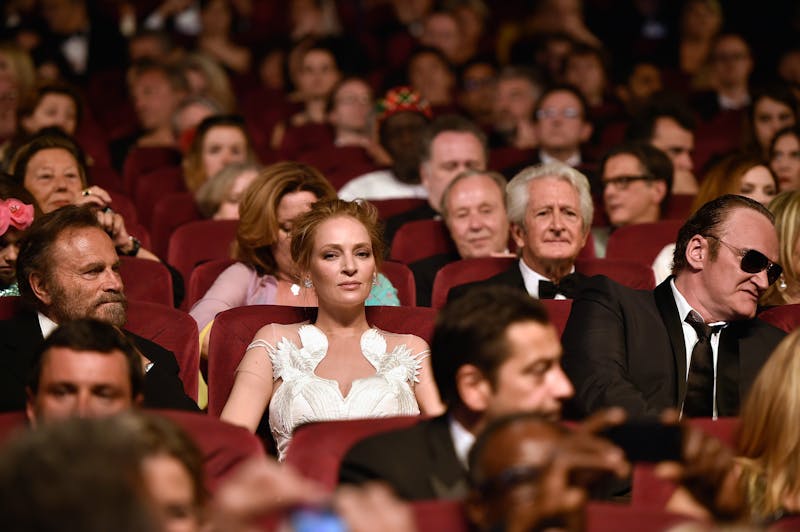

Or perhaps she accepts his definition of her worthlessness and his right to disparage her, so she’s not even angry, just miserable because she believes in her own inferiority. This is another kind of hell in which a lot of people reside. Don’t think of the warrioress Uma Thurman in the film Kill Bill, where she uses a samurai sword to slice off the top of an adversary’s head; think of the actual Uma Thurman, who seemed, before #MeToo, to have long normalized her abuse by director Quentin Tarantino.

Uma Thurman and Quentin Tarantino at the Cannes Film Festival closing ceremony in 2014. Pascal Le Segretain/WireImage/Getty

Uma Thurman and Quentin Tarantino at the Cannes Film Festival closing ceremony in 2014. Pascal Le Segretain/WireImage/GettyBoth Chemaly and Traister see Thurman as a counterexample to the more unrestrainedly angry women they describe. When Thurman was asked in October 2017 what she thought about Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo insurrection, she was reluctant to vent: “I don’t have a tidy sound bite for you,” she responded, “because I’ve learned—I am not a child—and I have learned that when I’ve spoken in anger, I usually regret the way I express myself. So I’ve been waiting to feel less angry. And when I’m ready, I’ll say what I have to say.” For Chemaly, this response shows that Thurman was fenced in by inhibitions; she should have spoken out in the moment. “The actress’s sense of her own position,” Chemaly argues, “reflected the precariousness of women, even powerful women, when they have this anger.”

Traister also analyzes that extraordinary footage of a clench-jawed Thurman (who is the daughter of a renowned Buddhist practitioner and scholar, and who perhaps has absorbed some non-Western ideas about the uses and abuses of anger). But she proposes that “sometimes, there is a strategy behind the suppression of rage; in Thurman’s case, she was waiting to tell her story in full.” Months later, in an interview with The New York Times, Thurman did just that, revealing that she considered that Tarantino had subjected her to “dehumanization to the point of death” when he forced her to perform a stunt in an unsafe car and she crashed, leaving her with permanent, painful injuries.

Thurman confided that up until that moment most of the abuse she had suffered from Tarantino—including spitting in her face—“was kind of like a horrible mud wrestle with a very angry brother.” The stunt setup was different, because it wasn’t just degrading but potentially fatal. “Personally, it has taken me 47 years to stop calling people who are mean to you ‘in love’ with you,” she reflected. “It took a long time because I think that as little girls we are conditioned to believe that cruelty and love somehow have a connection and that is like the sort of era that we need to evolve out of.” That is, women are conditioned to accept abuse and to accept it as its opposite (and to keep letting boys knock down their towers). The power to define your own experience is one of the powers that matters most.

Thurman impugned the reputation of two powerful men she’d worked with to speak of her own struggle and the plight of women exactly as she wanted to. She waited until she could be considered and effective. Her goal was not just what we call letting off steam—an Industrial Revolution-era metaphor that casts human beings as machines in which pressure builds up and must be released. Thurman’s goal was apparently to tell the truth in a way that had consequences, for the men who mistreated her and for the public at large—and perhaps for participants in the feminist insurrection underway, because stories like hers can fortify other women and the movement for women’s rights.

Anger itself is a catch-all term for a lot of overlapping but distinct phenomena. Among them are outrage, indignation, and distress, which are commonly born of empathy for the victims rather than animosity toward the victimizers. These feelings, which may last a lifetime, may not include the temporary physiological reaction that is bodily anger, with rising blood pressure and quickened pulse, tension, and often a surge of energy. That reaction is, in the moment, a preparation to respond to danger. It may be useful if you’re actually being attacked; when it becomes a chronic state, it turns the body against itself with impacts that can be devastating or even fatal.

I have often been struck by how some of the people who have the most grounds for anger seem to have abandoned it, perhaps because it could devour them. These are the falsely accused prisoners, farmworker organizers, indigenous rebels, black leaders, who are closer to the sage than to the samurai in our story, and powerful when it comes to getting things done and moving toward their goals.

I had a formative experience in the mid-1990s, when I was working with activists trying to expose the effects of depleted uranium on people who had been exposed to it in the 1991 Gulf War and at American weapons testing sites. I took two dedicated experts to a radio station, where they and the radio host talked at cross purposes throughout the interview. My colleagues were driven by love and compassion for the soldiers and the civilians in the United States and Iraq exposed to the stuff, and they wanted to talk about the suffering and the solutions. Their interlocutor—who if he were female might’ve been called histrionic, self-involved, and volatile—wasn’t really interested; he seemed to be motivated by hatred of the government and kept trying to turn the conversation to indictments of the institutions of power. He missed what his subjects were trying to say as he tried to beat their story into his mold.

Most great activists—from Ida B. Wells to Dolores Huerta to Harvey Milk to Bill McKibben—are motivated by love, first of all. If they are angry, they are angry at what harms the people and phenomena they love, but their urges are primarily protective, not vengeful. Love is essential; anger is perhaps optional.

Katherine Sanchez, a 16-year-old with curly hair and glasses, is unique among her peers at Stuyvesant, one of eight specialized high schools considered the “crown jewels” of New York City’s public education system. In seventh grade, when she found out about the entrance exam—a single three-hour test known as the Specialized High School Admissions Test, or SHSAT—she enrolled in a local prep school on the weekends. During the summer before eighth grade, Sanchez upped that commitment to five days a week, spending four hours each day being taught to the test. “You’re not learning material that’s relevant,” Sanchez told me. “You’re like, ‘How can I do these questions as fast as possible? How can I get used to these questions?’”

Of course, other students at Stuy also spend years cramming for the SHSAT. But unlike the vast majority of them, Sanchez is Latina. In 2016, Stuyvesant’s school newspaper found that, in comparison to Asian students, black and Latinx students were more likely to start studying later and on their own. Even in prep school, Sanchez recalled being the only Latina in a majority-Bengali class. Aside from kids in the honors class, most of the students in her middle school in the Bronx hadn’t heard of the SHSAT or specialized high schools.

In fact, Sanchez was told that she was the first person from her middle school to get into Stuyvesant in over a decade. “I don’t know anyone from my school who takes the 2 uptown after 42nd Street,” Sanchez told me in August, as she gave me a tour of Castle Hill, the predominantly working-class Latinx and black neighborhood where she grew up. When pressed, she conceded that she had heard rumors of a freshman at Stuy who also lives in the Bronx.

Stuyvesant has been criticized in recent years because of one stark fact: almost no black or Latinx students attend. In the 2015-2016 school year, the student body was 74 percent Asian-American and 20 percent white. Only 3 percent of students were Latinx and even less—1 percent—were black. This school year, black and Latinx students made up only 10 percent of offered seats across all eight specialized high schools, despite making up nearly 70 percent of the city’s public school population overall.

Sanchez, whose parents immigrated from the Dominican Republic, is acutely aware of the disparity. She had rarely even gone into Manhattan before high school, let alone the posh neighborhood of Tribeca where Stuyvesant is located. Entering the school itself was a culture shock, especially when it was clear many of the students already knew each other. “Waiting on the bridge for the doors to open on the first day was so scary, just standing there,” Sanchez said. “Everyone was in clusters, but I knew nobody.”

In June, Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed changing the admissions policies of the city’s specialized high schools in an effort to integrate them. Under de Blasio’s proposal, the SHSAT would be phased out over three years and eventually replaced with a system that automatically admits the top 7 percent of students from every middle school in the city, based on a combination of grades and state exam scores. He also wants to expand the Discovery Program, which sets aside a certain number of seats for low-income students. According to city officials, the impact of eliminating the test would be sweeping: When the new plan is fully implemented, 45 percent of offers would go to black and Latinx students.

Stuyvesant has been criticized in recent years because of one stark fact: almost no black or Latinx students attend.In response, many in the city’s Asian-American community, which is represented in lopsided numbers in the city’s specialized high schools, rose in protest. Spurred mainly by New York’s vocal Chinese-American community and alumni groups, protesters amassed outside de Blasio’s office, chanting, “Keep the test!” They claimed that the move was racist, targeting a disadvantaged minority that historically has had little clout in New York politics compared to other minorities. Their protests were quickly plastered all over the news, adding yet another layer of racial tension to the effort to fix the most segregated school system in the country.

Though the plan did not pass muster with the state legislature, it created the opening for a summer of outrage from members of the Asian community, some of it fueled by legitimate grievances (a “profound sense of powerlessness” as Jiayang Fang put it in The New Yorker), some by resentment toward other minority groups. As Kenneth Chiu, president of the New York Asian American Democratic Club and one of the most outspoken leaders against de Blasio’s plan, told NY1: “He never had this problem when Stuyvesant was all white. He never had this problem when Stuyvesant was all Jewish. All of a sudden, they see one too many Chinese and they say, ‘Hey, it isn’t right.’”

The outrage surrounding De Blasio’s plan also prompted some difficult questions: If racial integration is essential to educational equality, as many education experts believe, then are Asian-Americans an obstacle to that equality? Is the scramble for opportunity the zero-sum game that Asian activists make it out to be? And, more broadly, where do Asian-Americans fit in this city’s minority politics?

From a young age, Amy Lam knew that specialized high schools were the path she was expected to take. “I didn’t have much of a choice,” said Lam, a 17-year-old senior at Brooklyn Tech. She started preparing for the SHSAT, which tests students on English and math, in sixth grade, two full years before the test is usually taken. She attended a free program that she was accepted into in the Upper West Side, but her mother felt that wasn’t enough, so she enrolled Lam into a second, paid program in Chinatown. At that point, Lam was going to test prep every weekday after school for two hours. On Saturdays, she went to both prep classes, studying from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

Lam grew up in a public housing complex in Chelsea. When her parents moved to New York City from China in the 1990s, they first worked as fruit vendors in Chinatown. Her mother, who speaks mostly Cantonese, is now a home attendant.

As we sat in the one-room office of New York’s Chinese Progressive Association, where Lam interned this summer to help register voters, she belied the stereotype of the personality-less Asian student who is interested in nothing but her studies. She was quietly confident, well-spoken, and fully aware of the politics surrounding the school she attends. She had already thought about what she might do with her life, saying that her dream college was Georgetown and that she was interested in pursuing a law career.

In Lam’s mother’s eyes, Stuyvesant and Bronx Science were the gold standard, while Brooklyn Tech was a safety school. What about other public high schools? “When I was researching high schools I would be like, ‘Hey mom there’s this good high school that’s not specialized,’” Lam said. “And she’d be like ‘Oh do you want that to be your other safety?’”

This intense focus on specialized high schools is common for New York’s Asian immigrant community. “My mom mostly talked to Asian-American moms,” Lam said. “She met them either at my test prep place, even on WeChat, and pretty much all they talked about on there was ‘Oh my son went to Bronx Science.’”

This do-or-die mentality is partly a product of New York’s labyrinthine public school system. The SHSAT offers a bright, simple path for the city’s poor Asian immigrant population, many of whom face language barriers and a dearth of accessible information. And in many of these immigrants’ ancestral countries in East Asia and South Asia, rigorous test prep is a cultural norm.

“A lot of newly arrived Asian immigrants have this erroneous idea that there are three public schools that are good and then there’s the abyss,” explained Amy Hsin, a professor of sociology at CUNY and a member of the city’s school diversity advisory group. “And we have these test prep companies who are feeding off of that fear. You see these immigrant families who don’t have a lot of money spending enormous amounts of money prepping these children to test to get into these schools.”

Katherine Sanchez, a 16-year-old at Stuyvesant, says, “I don’t know anyone from my school who takes the 2 uptown after 42nd Street.”

Katherine Sanchez, a 16-year-old at Stuyvesant, says, “I don’t know anyone from my school who takes the 2 uptown after 42nd Street.”This deep investment is evident in the numbers: In addition to dominating Stuyvesant, Asians comprise 62 percent of the student body at Bronx Science, and 61 percent at Brooklyn Tech. New York City’s public school population itself is 16 percent Asian. (White students are also overrepresented, garnering 27 percent of offers to specialized high schools this year, despite the fact that they make up 15 percent of the city’s students.) Their outsized presence makes them wary of change, particularly since de Blasio didn’t offer Asian-American communities any kind of recompense for a proposal that would disproportionately affect them. They would just have to take the hit.

Asian-American community groups were blindsided by the mayor, whose office failed to consult them before the proposal went public. Shino Tanikawa, a school integration advocate, told me that de Blasio’s proposal was part of a depressingly familiar pattern of Asian-Americans either being lumped in with white people or brushed aside. Tanikawa agreed that the admissions system needs to be reformed, but pointed out that for de Blasio “to not even talk to any Asian community leaders before he made the announcement, it’s disrespectful. It’s another example of, what about us, do we not exist?”

Richard Carranza, New York City’s new school chancellor, made matters worse when he bluntly told a local news organization, “I just don’t buy into the narrative that any one ethnic group owns admission to these schools.” And by failing to get buy-in from New York’s Asian-American community, de Blasio undermined his own project. “Those people are needed,” Mae Lee, executive director of the Chinese Progressive Association, told me, referring to the mainly Chinese-American contingent that is rallying against de Blasio’s plan. “We need to draw those people in more and it’s not being done.”

It didn’t help that it was easy to read de Blasio’s announcement as a cynical political move. He campaigned on integrating specialized high schools in 2013, but he let the issue languish until this summer. De Blasio has often said that his hands are tied because reforming the admissions system needs approval by the state legislature, but he also announced it less than a month before the end of the legislative session, meaning that it was almost surely going to be shunted to next year—which is exactly what ended up happening. And if he wanted to, de Blasio could re-designate five of the specialized high schools and change their admissions policies on his own.

Unless New York gets rid of elite schools altogether, which some advocates have in fact proposed, it will have to diversify them in some way.Furthermore, the focus on specialized high schools, which make up only 6 percent of the city’s entire public high school system, fails to address the greater, systemic problem of school segregation throughout the city. “It really is a challenging issue because it ends up being a debate about a small number of schools that you can’t really have without opening up a much bigger questions about screening,” said Halley Potter, a fellow at The Century Foundation who focuses on integration policy in New York. “I’m hopeful that a year from now we can look back and say this is just one of multiple fronts that the administration has been looking at to tackle segregation.” Addressing just a few high schools out of an entire K-12 system is, in many ways, a distraction from the bigger issues.

Still, the fact remains that specialized high schools are in dire need of integration. Unless New York gets rid of elite schools altogether, which some advocates have in fact proposed, it will have to diversify them in some way. This inevitably means that Asian-Americans will have to figure out where they fit into this new reality—and, perhaps, reassess their political priorities when it comes to their kids and New York City’s school system.

Sanchez took me to a small park in Castle Hill not far from where she grew up, before she moved to a one-bedroom apartment in Morris Park with her mother, her mother’s boyfriend, and her three siblings. Sanchez now finally has her own bedroom, an exciting development that she told me she is definitely “still not over.” When we first started speaking, Sanchez was a little nervous, but quickly opened up about her experiences. Despite her criticisms of New York’s school system, Sanchez cheerfully pointed out all the things she loves about Stuyvesant—her peers and teachers, the fact that Tribeca is “really nice.” She told me that she wants to go to Wesleyan, but is worried about burdening her mother with the cost of tuition—a whole other educational system they’ll have to navigate.

The test’s proponents claim that the SHSAT is the only truly meritocratic method of admitting students into specialized schools, and that getting rid of it will compromise these schools’ academic integrity. This is despite the fact that the test itself has been subject to very little evaluation. In August, the education news site Chalkbeat obtained through a public records request a 2013 study from the mayor’s office that de Blasio declined to release, showing that the SHSAT is a strong predictor of academic achievement. Yet outside experts told Chalkbeat that the study didn’t answer the question of whether alternative admissions methods would admit just as strong or even better students.

Hsin, the sociology professor, told me, “If you were to put aside any concerns about goals of diversity at all and you just wanted to come up with mechanism for identifying the most talented individuals to be admitted to specialized high schools, you would never come up with the admissions policy you have now.” Grades, which are repeated measures over time, are considered better indicators of academic acumen. It’s also been shown that they are better than standardized test scores when it comes to predicting success for black and Latinx students.

And if you put aside the evidence—or lack thereof—regarding the effectiveness of the test, defending the status quo means defending the idea that admitting black and Latinx students would bring down the quality of the student body, as New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones has pointed out.

This racist principle is baked into the history of the admissions policy itself. The original bill that mandated the use of a single standardized test was passed in 1971 by state legislators in order to preempt moves by the city to try to make the specialized schools more diverse. According to Politico, state legislators at the time argued that the bill would “protect the current status and quality of specialized academic high schools in New York City.”

Sanchez told me that many of her peers at Stuyvesant have been talking about the mayor’s proposal since it came out. Common remarks that she’s heard include things like, “People aren’t being accepted because they aren’t smart” and “Stuy is ruined.” I asked her how she feels when she hears those responses. Sanchez paused for a beat, then said, “I think it’s just insensitive to think that way.”

Asians in America have long sat at the messy crux where minority politics and education meet. They are often the poster-children of conservative attempts to roll back affirmative action and integration, despite being some of these policies’ biggest beneficiaries. The model minority myth—the idea that Asians are successful because they have better values and work harder than other minorities—is pervasive, and often used as a cudgel by whites against black and Latinx Americans for their supposedly wayward values and lax worth ethic.

The sight of Asian-Americans marching against integration efforts in New York City plays into these storylines. It is why Donald Trump’s Justice Department is siding with Asian-American students challenging affirmative action programs at Harvard, which they say discriminate against them by privileging less qualified students.

A survey shows that the Asian-American opposition to affirmative action is almost entirely driven by Chinese-Americans.How did they reach this point? For one, because most of the Asian adult population are immigrants, they lack a lived understanding of America’s racial history. Asians have been excluded by this country’s racist immigration policies (see: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882), but they have also benefited from the loosening of immigration laws in 1965 that brought in more highly educated Asian immigrants. Those trends are set to accelerate: The foreign-born population in the U.S. is at a record high thanks to Asians, according to new Census data, and more Asians with college degrees are expected to emigrate to the country in coming years.

There is also the glaring fact that Asian-Americans—who hail from a vast continent composed of different cultures and ethnicities—are far from a unified group. In fact, a survey by AAPI Data, a policy research site, shows that the Asian-American opposition to affirmative action is almost entirely driven by Chinese-Americans.

Historically, Chinese-Americans have been on both sides of the civil rights divide. OiYan Poon, a professor at Colorado State University, noted two examples that should have resonance for Asian-Americans involved in the ongoing controversies surrounding minority rights and education. First was the case of Gong Lum, a Chinese immigrant who lived in the Jim Crow South in the 1920s. When Lum’s daughter was placed in a colored school, he sued, trying to get his daughter into the local white school. Lum lost the case in Supreme Court, but the battle he chose to fight—securing the privileges of whiteness for his daughter, rather than against a racist system—is instructive. “You can imagine how that case could have been a different possibility,” Poon pointed out. “It could have been Brown vs. Board of Education. Instead Gong Lum argued, ‘We want to be white.’”

Poon juxtaposed this approach with the 1974 Supreme Court case Lau v. Nichols, in which Chinese students who weren’t fluent in English had been recently integrated into the San Francisco Unified School District, which wasn’t providing them with English language instruction. The parents of Kinney Kinmon Lau, along with other non-English-speaking Chinese parents, argued that their Fourteenth Amendment rights were being violated since their children did not have equal educational opportunities. They won the case and secured the right to supplemental language education for non-English speaking minorities across the board. In collaboration with the Latinx community, Poon explained, the Chinese community was able to “push for systemic transformation and totally new possibilities.”

In New York today, members of the Asian community have lined up behind a system that results in blatant racial disparities. And they are doing so without examining the costs this system extracts, alongside the clear benefits it provides to a select few. The SHSAT effectively functions as a tax on poor Asian immigrants, both in terms of the actual dollars spent on prep courses as well as the years of childhood spent studying for a test that has little real-world relevance. “Thirteen- and 14-year olds don’t want to spend a lot of their sixth and seventh grade locked up in a classroom on weekends preparing for this dumb test,” Jade Wong, a daughter of Chinese immigrants and a senior at Brooklyn Tech, told me.

Lam said that when her mother found out about de Blasio’s plan, even she acknowledged that “maybe now certain students can focus more on their grades in middle school, focus into getting into a high school they would actually like to go, that they won’t have to study hours and hours to get into.” Potter, the education policy researcher, pointed out that in Brooklyn’s 15th District, which is going through a similar debate about integration and screening, she found that even advocates of screening recognized that the system felt broken. “If we started with this premise around specialized high schools,” Potter said, “we would find many folks in the Asian American community for whom that would resonate.”

In a broader sense, these specialized schools not only fail the black and Latinx community, but cannot even serve the vast bulk of the disadvantaged Asian-American community. Forgotten in the debate are the Asian children who are turned away; the ones who get in, but then struggle with mental health issues; the ones who would have flourished in different or more diverse schools.

Despite media headlines that might indicate otherwise, the city’s Asian-American community—which, again, includes an impossible multitude of ethnicities and immigrant experiences—is far from unified in opposition to the mayor’s plan. In July, a group of Asian-American alumni from specialized high schools published an op-ed that called for reform of the admissions process, writing, “Asian Americans ought to stand in solidarity with all marginalized communities by advocating for equity in the educational opportunities and outcomes of all New York City students.” That same week, Asian-Pacific American community groups released a statement arguing that “diverse and inclusive school environments are beneficial to all students” and that the city needs to “address inequities in education across Pre-K through 12th grade and examine current processes and admission policies.”

Barring action from politicians, Asian parents will also have to be convinced that there are alternative paths to success in this country, and that the binary of “test or no test” is failing all minorities in one way or another. As Lam put it to me, “It would benefit parents to know that it doesn’t have to be this way.”

No comments :

Post a Comment