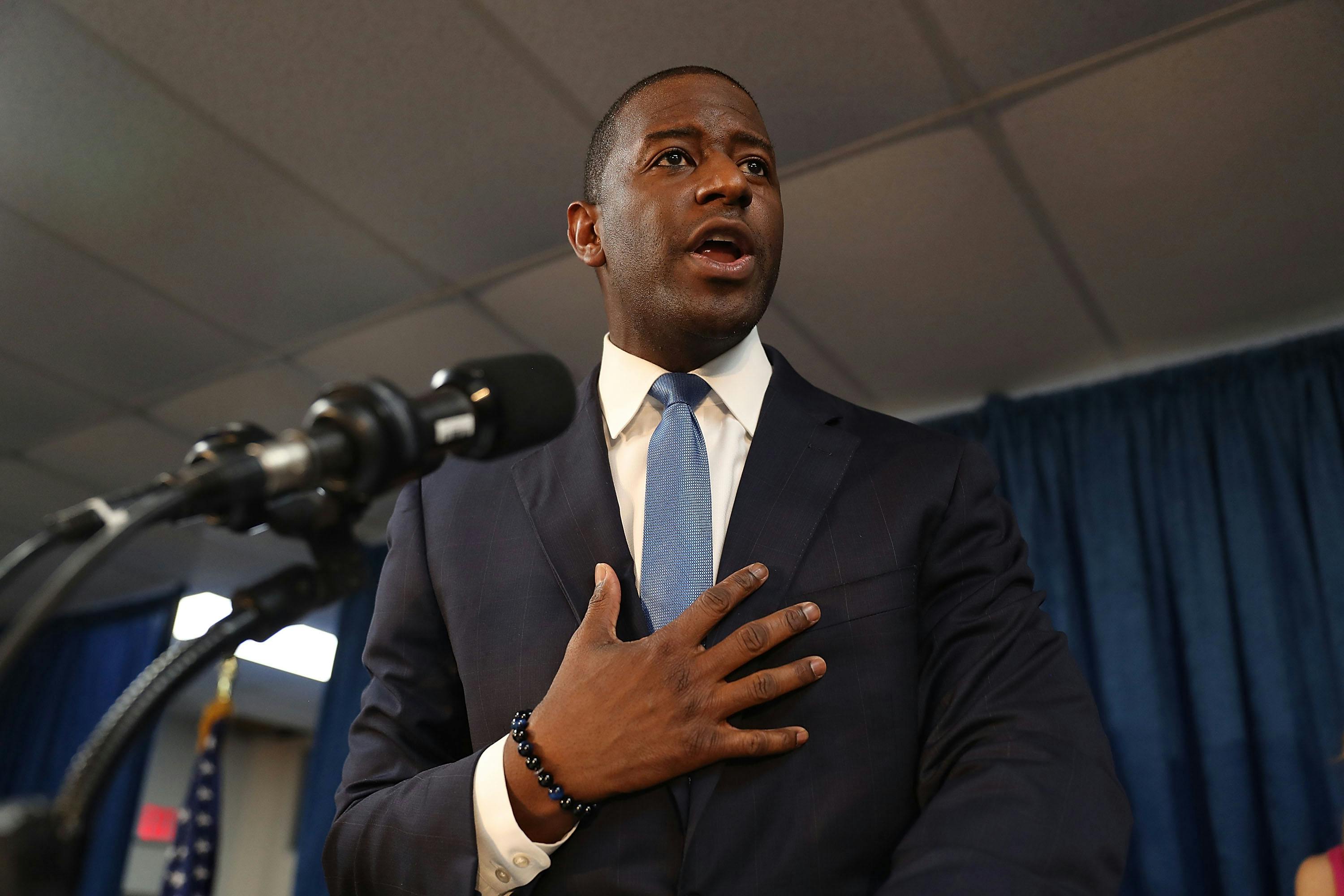

Chris King wasn’t the person most Florida liberals expected Andrew Gillum to name as his running mate in the state’s gubernatorial race. A white, evangelical Christian who made a fortune buying up dilapidated Florida apartment complexes after the 2008 crash and refurbishing them as affordable housing, the Winter Park businessman had run against Gillum in the Democratic gubernatorial primary earlier this summer—and lost spectacularly, finishing fifth in the primary, with less than 3 percent of the vote.

His religion might have had something to do with his loss. King has called himself “the case study of whether faith is a deal killer in the modern Democratic Party.” But Florida, like many states, has a highly secular Democratic base that dominates the primaries. With the evangelical community nationally so firmly aligned behind the conservative right, the mere fact that King, who had never run for office before, was an evangelical, and a proud one at that, may have hindered his chances.

Evangelicalism might have held King back in the Democratic primary, but in a statewide general election, his ties to the Christian community could be an asset, and Gillum’s decisions of late suggest he understands that. Gillum himself is Baptist, and in August he spoke to supporters outside the Bethel Church in Richmond Heights, the South Dade neighborhood where he grew up. Apart from than his numerous visits to African American churches and appearances with black preachers, Gillum did not explicitly raise religion, nor, for the most part, did his opponents or interviewers. Still, his choice for lieutenant governor suggests that he will lean into it in his quest to win the governorship.

Since Gillum named him his running mate, King has insisted that “this is not a political marriage—this is not a marriage of convenience.” Regardless, it makes strategic sense. Barack Obama carried Florida with help from the young white evangelicals in the state. They may not be the voters who decide the primaries, but they are an important and often overlooked demographic in general elections within Florida and throughout the South. With King on the ticket, Gillum can craft a campaign message that mixes evangelicalism and left policies—a powerful combination that could provide a path forward for Democrats looking to win back seats in the Sun Belt.

This won’t be an easy sell. “Eighty percent of white evangelicals would vote against Jesus Christ himself if he ran as a Democrat,” Amy Sullivan wrote in the New York Times in March. Even though the president was married three times, divorced twice, and has a string of lawsuits and debts to his name, the white evangelical community continued to support him. Nationally, he got 81 percent of their votes in 2016. In Florida, he earned 86 percent. And despite being a lifelong Methodist and churchgoer herself, Clinton only got 19 percent. Still, that’s enough to open up an opportunity for Democrats in the South.

The rough political calculus in Sun Belt swing states like Florida and North Carolina is this: A coalition of African Americans, Hispanics (except older Cubans in Miami), single women, Jews and other liberal whites, millennials who vote, the LGBT community, and union members (except police and firefighters) usually brings the Democratic vote total to about 48 percent. In some election cycles, a strong enough candidate or a galvanizing issue can be sufficient to attract a smattering of suburban centrist swing voters who can help carry the state or district. Evangelicals are another crucial demographic. If Democratic candidates can pull in more than 19 percent of white evangelicals, say 25 or 30 percent, they can win.

In Florida, the complicated racial dynamics of the state make independents and white evangelicals doubly important. Latinos are split between the Democrats and the GOP. African Americans almost universally vote Democratic in Florida, as elsewhere in the Sun Belt. For them, the main issue is turnout. Thus the effective battleground is for a sliver of white voters: independents and winnable evangelicals. In fact, in 2008, an increased minority of white evangelicals was thought to have helped provide the margin of victory for Obama in both North Carolina and Florida.

Democrats have struggled to replicate his success in recent years, but according to Aubrey Jewett, a political scientist at the University of Central Florida, the reasons are more cultural than political. “These Christians tend to be more progressive in their political views,” Jewett told me, “but sometimes feel like the Democratic Party at best grudgingly accepts their support and at worst is outright hostile to their religious values.” That’s where a candidate like Chris King comes in.

Tall and handsome, with an incandescent smile and a Norman Rockwell family, the 39-year-old King has undeniable charisma. A graduate of Harvard and the University of Florida Law School, he’s a liberal who ticks all the right boxes, beginning with “common sense” gun control: banning assault weapons, high capacity magazines, and bump stocks; instituting enhanced screening, including at gun shows; and repealing Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law.

King also wants to raise the state’s minimum wage; legalize medical marijuana; welcome Syrian and other refugees; accept federal Obamacare Medicaid subsidies for the working poor; and restore voting rights to nonviolent felons. He opposes the state’s voter ID law, which he says are “part of institutional racism in Florida,” as well as private prisons, fracking, and offshore drilling. He was also the only gubernatorial candidate in Florida to categorically oppose the death penalty and prompted most of the others to refuse donations from the sugar industry. And, unlike most evangelicals, King unequivocally supports abortion rights and fully funding Planned Parenthood.

At the same time, King is also a lifelong, evangelical Christian: In high school, he belonged to the Fellowship of Christian Athletes; at Harvard, he was affiliated with Campus Crusade for Christ. Now, he is an elder at the nondenominational, evangelical church where the family worships in Orlando. His mother-in-law is a religious broadcaster with Good Life Broadcasting’s WTGL-TV Channel 45 in Lake Mary.

King didn’t campaign as a Christian candidate. However, the question often came up, and when it did, he was quick to connect it to the policies he advocated on the stump. “My faith always propelled me to serve others and to care about the needs of folks who’ve not had a voice and who need an advocate,” he told the Daytona Beach News-Journal. “So my politics are really a reflection of that. For the last 30 years, I would say that the Christian faith has in many ways been hijacked by a very conservative Republican ideology that is not reflective of a commitment to serve, and care for, and lift up people of all backgrounds. My politics I think reflect a much more comprehensive view of the Gospel of Love.”

Most Democrats today tend to run largely secular campaigns, but not so long ago, many used overtly religious language. For much of the twentieth century, various Christian reform movements were associated with the Democratic Party, from William Jennings Bryan to Jimmy Carter, the first declared evangelical. Child labor, women’s suffrage, unions, civil rights, and the fight to end the Vietnam War were all fueled by the religious left.

Returning to such language could be particularly useful at this political moment. Gillum and King are running against Ron DeSantis, a Republican congressman who has overtly aligned himself with Donald Trump on everything from immigration to trade to law and order. As Gillum and King look to draw out contrasts with their opponent, religion could help them campaign for a more compassionate government that helps the poor, the disenfranchised, immigrants, people with disabilities, and the unemployed. “King’s unusual combination of religion and progressivism could make him more palatable to some voters,” said Donald Davison, a political scientist at Rollins College in Winter Park.

Of course, King won’t ever be able to win over all the evangelicals in the state. Even for young, progressive churchgoers, his support of abortion rights “still may be a deal breaker,” Jewett noted. But it does provide a test case for what candidates on the left can do when they weave religion into their rhetoric—and perhaps even a path forward for 2020.

Barack Obama became president in 2008 with the help from white evangelicals, and there is no reason why Florida Democrats cannot use their shared concerns about social and economic justice and compassion for the disenfranchised to reach out to this winnable demographic.

After all, as Myriam Renaud, a religious scholar at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, has written, “If progressives hope to recapture the White House, they will have to persuade most, or all, of the white evangelical Christians who switched from Obama to Trump to switch back to their next candidate.”

“When it comes to accuracy,” organizational psychologist Adam Grant has written, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is better than a horoscope but less reliable than a heart monitor. Fashioned in the first half of the twentieth century by a mother and daughter with no formal training in psychology, the test inventories your predispositions along four different axes—introversion/extraversion, sensing/intuition, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving—and sorts you into one of 16 discrete types. This system has no basis in science, critics point out; people’s personalities can’t be reduced to simple binaries, and those who answer the questions more than once often arrive at completely different types each time. Curiously, it remains one of the most popular personality tests in the world today.

THE PERSONALITY BROKERS: THE STRANGE HISTORY OF MYERS-BRIGGS AND THE BIRTH OF PERSONALITY TESTING by Merve EmreDoubleday, 366 pp., $27.95

THE PERSONALITY BROKERS: THE STRANGE HISTORY OF MYERS-BRIGGS AND THE BIRTH OF PERSONALITY TESTING by Merve EmreDoubleday, 366 pp., $27.95Taken by over two million people each year, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is used by universities, career coaching centers, federal government offices, several branches of the military, and 88 of the Fortune 100 companies. Even if you’ve never been administered an official version of the test—which the publisher CPP Inc. currently sells for $49.95—chances are you’ve ascertained your type at some point from one of the many MBTI knockoffs that circulate on the internet. You’re likely familiar with the difference between Is (introverts), who focus more on their inner worlds, and Es (extraverts), who focus on the outer world; you may also know that Ts (thinking types) make decisions based on logic and consistency, whereas Fs (feeling types) make decisions based on the people involved and the individual circumstances. Perhaps you’ve even let the Myers-Briggs type listed on someone’s dating profile determine the direction of your swipe.

How did the test establish such wide appeal? The answer, Merve Emre proposes in her new book The Personality Brokers, lies in its early-twentieth-century origins. The women who conceived of the MBTI and fought for its validation in the years during and after World War II were, she writes, “among the first to perceive how hungry the masses were for simple, self-affirming answers to the problem of self-knowledge.” Yet, as she also shows, the MBTI was always intended to be more than just a springboard for therapeutic self-reflection. It is, both by design and in practice, a tool of workplace management. The story of its success tracks the rise of a new type of employee, who, propelled by the gospel of self-knowledge, is expected to mold her character to the perennially shifting demands of the labor market.

If the MBTI attempts to measure personality in the abstract, The Personality Brokers captures the specific, idiosyncratic personalities of the test’s two creators, Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers. While both women were, on paper, homemakers for the majority of their adult lives, they were also autodidacts, published writers, and zealots of a distinct sort. As affluent, educated women, both mother and daughter were alternately enabled and constrained by their circumstances in the postwar period, a tension that would bend the trajectory of the MBTI introduction into the world.

Katharine, born in 1875, grew up religious and bookish. She enrolled in Michigan Agricultural College at the age of 14 and there met another young prodigy, Lyman Briggs, whom she married after graduation. Their daughter, Isabel, was born in 1897, and Katharine promptly began a series of small experiments designed to mold her child into a genius. Influenced by the popular parenting literature of the time, which sought to apply the principles of scientific management to motherhood, she dubbed the family’s living room the “cosmic laboratory of baby training,” and conscripted Isabel into near-daily behavioral drills. In one such exercise, Katharine would present her toddler daughter with a tempting yet potentially dangerous object, such as an open flame, and snap “No! No!” when Isabel reached for it, a ritual often accompanied by spanks or slaps on the child’s hand. On the occasions when Isabel demonstrated adequate obedience, Katharine regaled her with inventive, winding fables about how the rugs and tables in their household had originated in mythical lands. She documented these practices in a journal, along with notes on her young daughter’s developing personality.

Isabel emerged from these years of her mother’s training sessions “not a genius” (according to Katharine) but nevertheless what today’s upper-middle-class parents would call high-achieving. She spoke full sentences at two, learned stenography at twelve, published short stories at 16, and at 17 she was accepted to Swarthmore College. It was there she met the man who would become her husband, future lawyer Clarence “Chief” Myers. She brought the family preoccupation with personality into this new relationship. “There ought to be some highly intelligent division of labor that can be worked out, so everybody works, but not at the wrong things,” she wrote in her diary during the first year of her marriage to Chief. Isabel was talking about men’s and women’s respective roles in a successful marriage, not about waged work. Yet the longing for a benevolent yet useful form of “people-sorting” would spur the invention of the Myers-Briggs test.

In 1923, her mother discovered a schematic for sorting people in a review of Carl Jung’s Psychological Types in The New Republic. Jung’s book laid out the theory that all people could be categorized according to distinct “type pair” binaries: extraverted and introverted, intuitive and sensing, thinking and feeling. The reviewer was critical, arguing that Jung’s methods were unscientific; Jung himself had, in fact, admitted that he based his types only on conjecture. Katharine was nonetheless entranced. She took up the taxonomy with zeal, poring over Psychological Types for the next five years.

For her, the type pairs provided an explanation for a lifetime’s worth of unarticulated desires and frustrations, losses and successes. She suddenly understood why, as an intuitive type, she had felt out of place at Michigan Agricultural College, where sensing types had dominated. Being a thinking type explained why, as a mother, she had gravitated toward strict baby-training rather than sentimental coddling. And, as an introvert given to long bouts of self-reflection, she believed she was, as Emre puts it, “incapable of moving through the world in a conventional manner.” Understanding type, and by extension, understanding oneself, she believed, would help every person find their rightful and harmonious place in society. Type, in other words, could “hasten the evolution of human civilization one personality at a time.”

It was Isabel who would adapt Jung’s type pairs to create the first prototype of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. In the years leading up to and during World War II, personality tests proliferated as a popular tool of workplace management in the United States, promising to help identify which employees were best suited to certain tasks (and which, by contrast, might be disposed to organizing unions). Upon learning of the burgeoning personality-consulting industry, Isabel devised her own questionnaire based on Jung’s types and called it, in tribute to her mother’s influence, the Briggs-Myers Type Indicator. (Later, when the test was commercialized, an adviser suggested swapping the order of the names to avoid the scatological connotations of the abbreviation “BM.”)

The majority of the personality tests that circulated during the postwar period sought to assign value to employees’ predilections, classifying a given worker, for example, as “normal” or “abnormal.” Isabel was interested in a gentler kind of Taylorism, one that made “every worker feel as if he was needed somewhere, doing something, no matter how unglamorous the task.” For Isabel, Emre writes, “the idea was not to accept work as a grim reality—the proverbial grind—but to set up the ideological conditions under which one would bind oneself to it freely and gladly, as a point of pride and a source of self-validation.” This relentless positivity persists today among adherents of Myers-Briggs, who, as Emre notes, insist that the questionnaire not be called a “test,” but rather an “indicator” that contains no wrong answers.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator would establish its foothold in the workplace when Isabel learned that Edward Hay, the father of her son’s classmate and a preeminent personality consultant, was short-staffed. She approached him for an apprenticeship in personality testing, and Hay took her on as a paid employee. Hay’s backing gave the MBTI the push it needed to take flight: At his company, Isabel devised the first commercial version of the type indicator, and over the next decade, sold it to clients ranging from leading insurance and utilities companies to the federal Office of Strategic Services, a precursor to the CIA that used the MBTI to assess the psychological fitness of potential spies.

According to Emre, Isabel took to the role of saleswoman enthusiastically and “was not shy about asking for help or using her family’s connections.” Among the institutions to whom she sold the test in the years after the war were Swarthmore (her alma mater), the National Bureau of Standards (the employer of her father, Lyman Briggs), and the Roane-Anderson Company, a defense contractor and contact of her father’s. Lyman, a board member of George Washington University’s medical school, also eventually encouraged the dean to allow Isabel to administer the test to the school’s med students in her first large-scale study.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the MBTI attracted interest from institutions including the Educational Testing Service in Princeton, New Jersey, and UC Berkeley’s Institute of Personality Assessment and Research. The latter, buoyed by grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and Carnegie Corporation, administered the indicator to Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, and other prominent writers and artists in an effort to establish a profile of the “creative” type. But these starry encounters were fleeting, and Isabel would see academia’s enthusiasm for the MBTI wane by the end of the ’60s. In 1975, in an effort to resuscitate the MBTI, Isabel sold the rights to Consulting Psychologists Press, a fledgling publishing company founded by two psychologists. The press was, Emre writes, “only too happy to market their wares to anyone who asked, so long as they were able to pay.”

By 1980, the year Isabel died, Consulting Psychologists Press estimated that over one million people had taken the MBTI. The company has since dropped its official name and rebranded simply as “CPP–The Myers-Briggs Company.” By 2012, sales of the MBTI and other forms of personality testing were bringing in about $20 million a year. And although few who take the test have ever heard of Isabel or Katharine, Myers-Briggs is now a household name.

The MBTI’s success is (to invoke another popular personality assessment device popular in the postwar period) something of a Rorschach blot: On one hand, you can see its enduring popularity as an inevitable end point of a deeply human urge to find comfort or purpose in a world often marked by injustice, failed relationships, and unsatisfying jobs. At the same time, you can see it as a tool of the managerial class that emerged during the height of Fordist production and mass standardization. With the push for workers to be more specialized in the postwar economy came the need for a group of people who could deduce exactly where to place each employee, how to maximize their productivity, and—perhaps most crucially—how to make them like it.

In the course of writing the book, Emre found herself increasingly and surprisingly sympathetic to the first of these interpretations. As part of her research, she underwent an official Myers-Briggs certification course and encountered more than a few true believers who experienced genuine revelations in their personal lives after learning about the intricacies of type through the course. Understanding type, multiple attendees insisted, had allowed them to completely transform their relationships. One woman, a sensing type (S), found new perspective on why she constantly fought with her mother, an intuitive type (N): “When I ask my mom for a recipe, she says ‘Just a dash of this, just a dash of that.’ But I’m like—Ma, how much is that? Give me a real measurement,” she explained. Other women, judging types (J), now had a language for why they were prone to clash with their perceiving type (P) husbands on family trips. In this setting, the scientific validity of the MBTI (or lack thereof) was completely beside the point. “For many of my fellow trainees, the five days we spent learning the language of type presented a rare opportunity to confront themselves, to speak their truths in a strange but useful tongue,” Emre writes.

But of the two million people who take the MBTI annually, exactly how many are actively seeking self-knowledge? According to one estimate, up to 70 percent of Americans have taken a personality test as part of a job application, which suggests that something more coercive is driving the $500 million personality-testing industry. While CPP officially discourages using Myers-Briggs for hiring or evaluation, the company is also clear that the test is (as its creators always intended) designed for management, touting Hallmark, Southwest Airlines, and Marriott Hotels as happy corporate clients who have used the MBTI to generate harmonious, productive offices simply through increased understanding of type. “The MBTI assessment helps leaders and teams by providing them with communication tools, helping them to recognize and celebrate their differences,” claims a spokesperson for Southwest in a CPP case study. “The teams then use this knowledge to achieve better results.”

Employees aren’t always so thrilled. In a 2012 article for The Conversation, management professor Robert Spillane noted that a survey of 8,000 Australian workers found that about half considered personality tests “personally invasive.” His own research further indicated that over 70 percent of MBA students who had undergone personality testing as part of their management training had done so against their will. Even questions that seem innocuous—such as, “At parties, do you: (a) stay late with increasing energy, or (b) leave early with decreased energy?”—come with a slight edge when it’s an employer who’s asking. Does staying late make you look irresponsible? Or does leaving early suggest a reluctance to put in long hours on the job?

The problem for workers required to undergo personality assessments, in other words, is not strictly that such testing is unscientific, but that it functions as a tool of soft control, by demanding access to workers’ interiority and obscuring the employer’s immense power in hiring and firing decisions with the language of “fit” or “type.” While the MBTI and other personality tests promise to help you find the best work to suit your personality, they also hint that showing that personality in a flattering light—not just during the application process but also in ongoing performance reviews—will be necessary if you want to find and keep a job. Though this pressure to conform is likely not what Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers envisioned for their creation, it’s not a wholly unexpected outcome of their penchant for “people-sorting.”

Recently, I encountered an online application for a white-collar job that instructed, “In 150 characters or fewer, tell us what makes you unique. Try to be creative and say something that will catch our eye!” What the employer was looking for, of course, was a glimpse of an authentic personality—but undoubtedly one that seemed disposed to authentically work hard and cheerfully, authentically melt into the office culture, and authentically get along with the boss. Maybe after all this time, the significant distinction between types isn’t between the Is and the Es, or the Ps and the Js, but between those who engineer our workplaces for productivity and those who must engineer our personalities to fit them.

Last week, in an anonymous New York Times op-ed, a senior Trump official attempted to reassure the public that members of the administration were actively impeding their boss’s wishes. One member of the public wasn’t soothed: Trump’s predecessor. “The claim that everything will turn out okay because there are people inside the White House who secretly aren’t following the president’s orders, that is not a check,” Barack Obama said in a speech. “That’s not how our democracy’s supposed to work. These people aren’t elected. They’re not accountable.”

It was interesting timing for Obama to condemn executive branch defiance. This week marks the tenth anniversary of the fall of Lehman Brothers, seen as the emblematic event of the financial crisis. And early in Obama’s first term, as he struggled to prevent further collapse, he faced similar insubordination from a key official: Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner.

According to credible accounts, Geithner slow-walked a direct presidential order to prepare the breakup of Citigroup, instead undertaking other measures to nurse the insolvent bank back to health. This resistance to accountability for those who perpetrated the crisis, consistent with Geithner’s demonstrated worldview, had catastrophic effects—including the Trump presidency itself.

Ron Suskind was the first journalist to dig out this history, which has been largely forgotten, in his 2011 book Confidence Men. On March 15, 2009, Obama’s economic team met to discuss Citigroup, which had seen its stock price plummet after reporting $8.29 billion in losses for the fourth quarter of 2008. Toxic mortgage securities still cluttered Citi’s balance sheet, and two government bailouts totaling $45 billion, plus $306 billion in loan guarantees, had failed to stop the bleeding.

Larry Summers, then the National Economic Council director, was intrigued by the concept of nationalizing the sickest commercial banks, similar to what Sweden had done a decade earlier. Summers had discussed the mechanics of it with FDIC chairwoman Sheila Bair, as she recounted in her 2012 book Bull by the Horns. Obama had already publicly rejected nationalization in an interview with ABC News, but his economic team had differing viewpoints, which they hashed out in the March 2009 meeting.

They decided that the remaining bailout funds would be used to support a “resolution” of Citi. The worst assets would be put into a “bad bank,” with shareholders wiped out and the rest of the firm downsized and restructured. Obama wasn’t exactly gunning for bank retribution, as his dismissal of the Swedish option showed, but he approved the order that night and tasked the Treasury Department with nailing down the details.

Geithner simply didn’t follow the request, failing to produce any proposal for the unwinding of Citi, according to Suskind. It was a classic Washington move: When your boss asks for something you don’t like, just ignore it and hope that the request isn’t necessary when the boss follows up.

Geithner and his bank regulator colleagues made sure a breakup wouldn’t be needed by using Federal Reserve loans, guarantees, and a third bailout to save Citi. Little was asked from the company in return. Geithner had devised “stress tests” to judge how large banks would handle another downturn, and Citi’s initial test estimated that the bank would need $35 billion in additional capital to reassure markets that it was safe. But Citi haggled with regulators, dropping their capital requirement to $5.5 billion, about the same as what the bank paid out in bonuses that year.

In Confidence Men, Geithner rejected Suskind’s account of the March 2009 meeting, saying, “I don’t slow-walk the president on anything.” But Obama didn’t deny it. Describing how he felt about Geithner’s response to his order, he said, “Agitated may be too strong a word.” He later added that “the speed with which the bureaucracy could exercise my decision was slower than I wanted.” As Suskind would conclude, “The Citibank incident, and others like it, reflected a more pernicious and personal dilemma emerging from inside the administration: that the young president’s authority was being systematically undermined or hedged by his seasoned advisers.”

Any objective look at Geithner’s actions in response to the financial crisis confirms that he would maximize his power on behalf of big banks, even if it meant going around his colleagues and his president. That included paying off AIG’s investment bank counter-parties at 100 percent instead of forcing a discount, or blocking Bair, the FDIC chair, from forcing higher capital rules on banks. Every action fit Geithner’s worldview: The financial system must be stabilized at all costs, as the only way to heal the economy so real people benefit. “We do not need to imagine that he was in the pocket of any one bank,” Adam Tooze wrote in the new book Crashed. “It was his commitment to the system that dictated that Citigroup should not be broken up.”

But this neglects the political implications of deploying massive resources to save Citigroup and Wall Street more broadly. Failing to hold anyone accountable for causing the Great Recession as the economy struggled to regain its footing generated significant public resentment, from the Tea Party on the right to Occupy Wall Street on the left. The same urgency and ingenuity was simply not adopted to save homeowners drowning in mortgage debt, which weighed down the overall recovery. Obama fired the CEO of GM, but no bank executive suffered for a moment. And people noticed.

The statistics of the era speak to this inequity. In Obama’s first term, the top one percent took more than all of the gains from the economy after the crisis. Meanwhile, at least 9.3 million families lost their homes to foreclosure due to the mortgage meltdown. For many Americans, the financial and psychological damage will be lifelong. But banks weathered the storm well, and this year posted record profits.

Propping up the existing system instead of overhauling it made it easier for Big Finance to pull off its comeback. Geithner’s stress tests are now seen as weak and easily gamed; Summers recently called them “comically absurd.” Banks like Wells Fargo continue to break the law with impunity, because virtually nothing is done to them when they get caught. A shocking number of those who wrote the Dodd-Frank financial reform now work for the financial firms succeeding at chipping away at it, including Geithner himself, who now runs a private equity firm that owns a predatory lender.

Today, some may welcome the internal dissension in the Trump administration. But Geithner’s actions to protect banks from the president he served, and the anger it bred at a “rigged” system, diminished the public’s faith in government intervention and helped install Trump in the White House. Ten years later, Geithner’s one regret, as he put it in the Times, was that regulators don’t have as much power now as he had then to bail out banks. But he wasn’t given that power unilaterally; he took it, and America is still dealing with the consequences.

New poll from Pew shows Facebook users are changing their privacy settings and deleting the mobile app.

New poll from Pew shows Facebook users are changing their privacy settings and deleting the mobile app. TrendForce expects a shortage of Whiskey Lake processors to impact notebook supplies while AMD's Ryzen Mobile processors are fully stocked and enjoying rapid uptake.

TrendForce expects a shortage of Whiskey Lake processors to impact notebook supplies while AMD's Ryzen Mobile processors are fully stocked and enjoying rapid uptake.

No comments :

Post a Comment