Even before Hurricane Florence made landfall in North Carolina on Friday morning, it had an impact: introducing the phrase “poop lagoon” to the nation.

As forecasters cemented the storm’s track, reporters began to warn that it was headed straight toward the heart of North Carolina’s hog farming country, where millions of gallons of pig feces was stored in uncovered pits. These man-made lakes of hog waste risked overflowing into adjacent drinking water sources if they became inundated with rain. And considering Florence’s predicted rainfall totals, they very likely would.

Overflows had also happened before, reporters noted. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd caused manure to spill “over thousands of acres of private and public lands and into the watersheds of four rivers that feed the second-largest estuary system in the nation,” according to the environmental news site Coastal Review. And during Hurricane Matthew two years ago, 14 hog manure lagoons became submerged. Drowned hog bodies were also found floating and decomposing in floodwaters in both instances, which created yet another source of potential disease pathogens.

As Florence approached, CNN, Vice News, NPR, and the Wall Street Journal all warned of a potential pig waste crisis. Less discussed, however, has been why this threat exists and persists, despite years of knowing catastrophic fecal overflows could happen during hurricanes. Surely, there are many reasons. But the most obvious is our appetites.

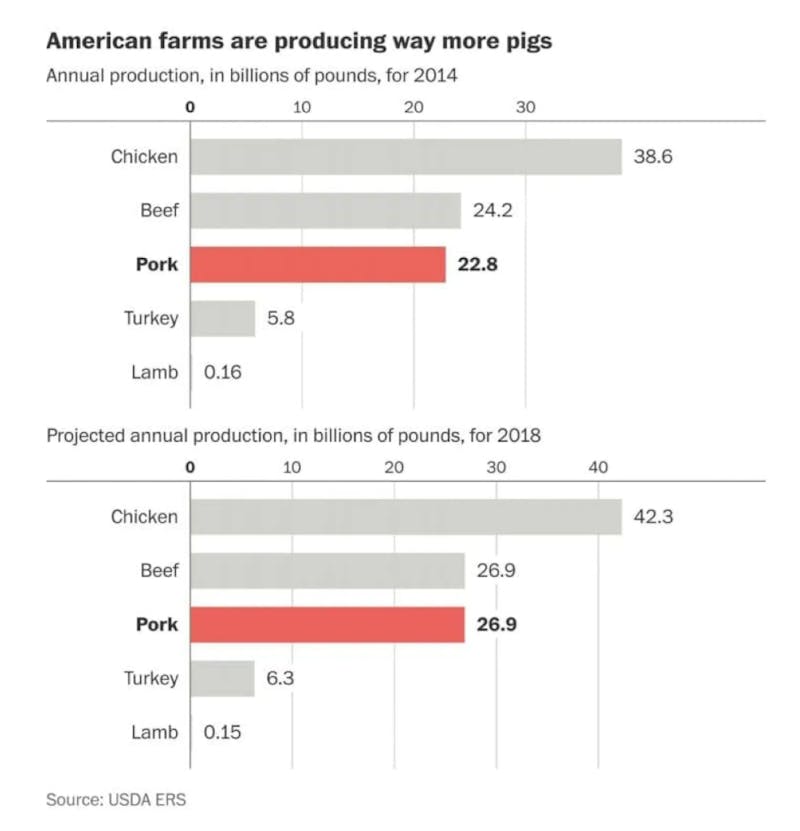

The Washington Post

The Washington Post“Americans are eating more pork now than they have in decades,” the Washington Post reported last year, citing Department of Agriculture statistics showing a spike in pork production. That spike was partially because of U.S. farmers exporting pork products to other countries, the Post noted; but also because “Americans have developed a new taste for pork, particularly bacon, as well.” The growing popularity of Asian cuisines have made dishes like bulgogi and banh mi, which often include pork, “among the year’s hottest foods.” The growing popularity of low-carbohydrate diets, too, has contributed to pork’s rise. Pork production may soon outpace beef.

The growing demand for pork, both here and abroad, has been an economic boon for North Carolina. Home to nine million hogs and more than 2,000 hog farms, the state is the nation’s second-largest pork producer. And to keep that pork cheap for U.S. consumers, most of the state’s pigs are kept in concentrated animal feeding operations, commonly called CAFOs. These are industrial farming operations where more than 1,000 animals are confined for at least 45 days or more per year in an area without vegetation.

A flooded hog farm and poop lagoon in North Carolina after Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The waste overflow from this lagoon ultimately infiltrated Wilmington, North Carolina’s water supply.John Althouse/AFP/Getty Images

A flooded hog farm and poop lagoon in North Carolina after Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The waste overflow from this lagoon ultimately infiltrated Wilmington, North Carolina’s water supply.John Althouse/AFP/Getty ImagesCAFOs are where the poop problem really comes from. On any type of farm, a grown hog would produce as much waste in a day as two to three grown adults. But on many of North Carolina’s hog CAFOs, as Pacific Standard recently described it, “feces, urine, and anything else that seeps beneath pens’ slatted floors—stillborn pigs, afterbirths, pesticides, blood—form a liquid slurry, which is then pumped into open-earth pits.”

In these deep pits, oxygen becomes deprived, and the waste can’t decompose as quickly. Thus, contaminants from the fecal matter “often leak into the ground,” Pacific Standard reported, citing “everything from noxious gases and heavy metals to over 100 microbial pathogens.” The manure also contains lots of nitrogen and phosphorus, which can spawn toxic algae if too much gets into nearby waterways. Nearby residents—mostly poor, and mostly African American—complain about the stench and runoff from these pits when the sun is shining. Those complaints seem like mere quibbles compared to what Florence could bring.

If American and foreign demand for pork keeps growing as it is now, the result won’t actually be more poop lagoons in North Carolina. In 2007, the state government banned waste lagoons from being built on new pig farms, in part due to the public health crisis Hurricane Floyd wrought in 1999. It does mean, however, that the old poop lagoons will remain in operation for as long as hog farmers feel they can make a profit. Considering America’s love for pork, that could be a very long time—and many more hurricane seasons.

Robert Mueller first dropped Paul Manafort into the criminal-justice system last October, and he’s been tightening the vise ever since. The special counsel has flipped Manafort’s close associates and used their testimony against him. He persuaded a judge to revoke Manafort’s house arrest and send him to jail for trying to tamper with other witnesses. And he made a convincing enough case for a jury to find Manafort guilty on eight fraud-related counts in last month’s trial in Alexandria, Virginia, all but guaranteeing the 69-year-old political operative a hefty prison sentence.

On Friday, Manafort finally cracked from the pressure. President Donald Trump’s former campaign chairman pleaded guilty to conspiracy against the United States and conspiracy to obstruct justice in a D.C. courthouse. He also admitted his guilt to ten charges on which the Alexandria jurors failed to reach a verdict. And in exchange for a lighter sentence to be determined later, Manafort gave Mueller his prize after eleven months of labor: a binding agreement to “cooperate fully, truthfully, completely and forthrightly ... in any and all matters as to which the government deems the cooperation to be relevant.”

This is the moment that Trump feared and tried to prevent. Manafort is one of the few people who can provide details about the extent of the campaign’s interactions with the Russian government during the last election. His extensive connections to Moscow-aligned figures in Eastern Europe make him the likeliest vector for whatever conspiracy may have existed between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin to sabotage Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid in 2016. Manafort’s cooperation will likely shed new light on key moments during that fateful year: He’s the only American, for example, who participated in the infamous Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 that isn’t related to Trump by blood or by marriage. Friday’s plea agreement could therefore increase the legal peril not only for the president, but also for his inner circle and members of his family who have already testified about the encounters.

The result is perhaps Mueller’s most important victory yet, and a vindication of his quiet, patient strategy in the investigation.Manafort’s guilty plea spares him from the financial and legal ordeal of facing a second trial in D.C. that was scheduled to begin later this month. The first charge relates to his work as a political consultant for pro-Kremlin political parties in Ukraine, where he amassed a small fortune and illegally funneled it back into the United States. “Manafort laundered more than $30 million to buy property, goods, and services in the United States, income that he concealed from the United States Treasury, the Department of Justice, and others,” the indictment said. “Manafort cheated the United States out of over $15 million in taxes.”

The second charge against Manafort is connected to his communications with other former conspirators earlier this year. According to the indictment, Manafort reached out to his associates, including Konstantin Kilimnik, a former business associate reportedly connected to the Russian intelligence services, to coordinate their testimony on matters related to his overseas work. Mueller first charged Manafort over this action—attempting to undermine the investigation—in June, which led a federal judge to revoke the 69-year-old lobbyist’s house arrest and let him await trial in jail.

The result is perhaps Mueller’s most important victory yet, and a vindication of his quiet, patient strategy in the investigation. Federal prosecutors in white-collar and organized-crime cases often begin by bringing charges against low-level members, often on unrelated charges. Investigators then work their way up the chain of command by offering leniency in exchange for cooperation and testimony against higher-level conspirators. Mueller has maintained the radio silence of a Soviet submarine captain since taking over the investigation last spring, but his prosecutions so far suggest that he’s employing a similar strategy against Trump and his associates.

What distinguishes Trumpworld from an organized-crime syndicate or a money-laundering bank, of course, is the presidency itself. Trump could use its powers to shut down the Russia investigation, fire Mueller and other top Justice Department personnel, and pardon his cronies with relative ease. That threat is now somewhat mitigated. Mueller’s team told the court during Friday’s allocution that Manafort had already begun providing them with information, which limits the practical impact of pardoning him now.

Moreover, in recent months, the president’s legal team occasionally suggested they might demand Mueller hew to a September 1 deadline, implying any major action after that would be interfering the November midterms. If Trump now attempts to halt Manafort’s cooperation with a pardon or other major move, he may face a similar quandary. Democrats are currently forecast to make major gains in the House of Representatives and have a slim chance at retaking the Senate. Given Mueller’s current popularity, any substantive steps against him would probably make a Democratic takeover of Congress—and with it, potential impeachment proceedings—even more likely. Manafort’s flip means Trump is damned if he tries to stop the Russia investigation before November and damned if he doesn’t.

It’s theoretically possible, of course, that Trump played no part in any possible collusion, and that Manafort doesn’t know anything that could implicate him. The president, like all potential defendants, is legally innocent until he’s proven guilty.

Trump and his allies, however, aren’t acting like innocents. Earlier this year, I wrote that the best available explanation for Mueller’s quiet moves and Trump’s noisy countermoves is that the president knows or believes that the special counsel can prove collusion. Many of the president’s most vociferous defenders operate under the assumption that Trump is guilty but Mueller won’t or shouldn’t find any proof.

Trump’s posture towards the investigation supports this view as well. After the twin blows last month of Manafort’s conviction in Virginia and Michael Cohen’s guilty plea in New York, the president praised his former campaign chief for not bending the knee to prosecutors. “I feel very badly for Paul Manafort and his wonderful family,” Trump wrote on Twitter. “[The Justice Department] took a 12 year old tax case, among other things, applied tremendous pressure on him and, unlike Michael Cohen, he refused to ‘break’—make up stories in order to get a ‘deal.’ Such respect for a brave man!”

Shortly thereafter, Trump reportedly told a Fox News reporter off camera that he was considering a pardon for Manafort. He then suggested in the interview that “flipping,” a common prosecutorial tactic, “should be illegal.” Rudy Giuliani, the president’s personal attorney, quickly briefed reporters that Trump and his legal team agreed that there would be no pardons until after Mueller’s investigation had ended. The implicit message seemed to be clear: As long as Manafort stays quiet, the president will spare him from prison when this all blows over.

That option now seems moot. It’s not clear what the president’s countermove will be. The White House’s only public response so far is to stress that Manafort’s legal troubles don’t directly affect them. “This had absolutely nothing to do with the President or his victorious 2016 Presidential campaign,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders told reporters on Friday. “It is totally unrelated.” Left unspoken were the two most important words: for now.

When socially privileged children are separated from their families at a tender age, some develop what psychotherapists have called “Boarding School Syndrome”: “a defensive and protective encapsulation of the self,” in which they learn to hide emotion, fake maturity, and assert dominance over anyone weaker. They develop loyalty to their institutional tribe and suspicion of outsiders; they become bullies devoted to winning above all. If these traits sound familiar, it may be because the men who sent Britain careening into the catastrophe of Brexit—David Cameron, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage—are all products of elite boarding schools, notorious symbols of social and economic inequality. These institutions—Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster and their ilk—may be quintessentially English, but, as they have become the ultimate educational status symbol for the global super-rich, their influence today extends across the world.

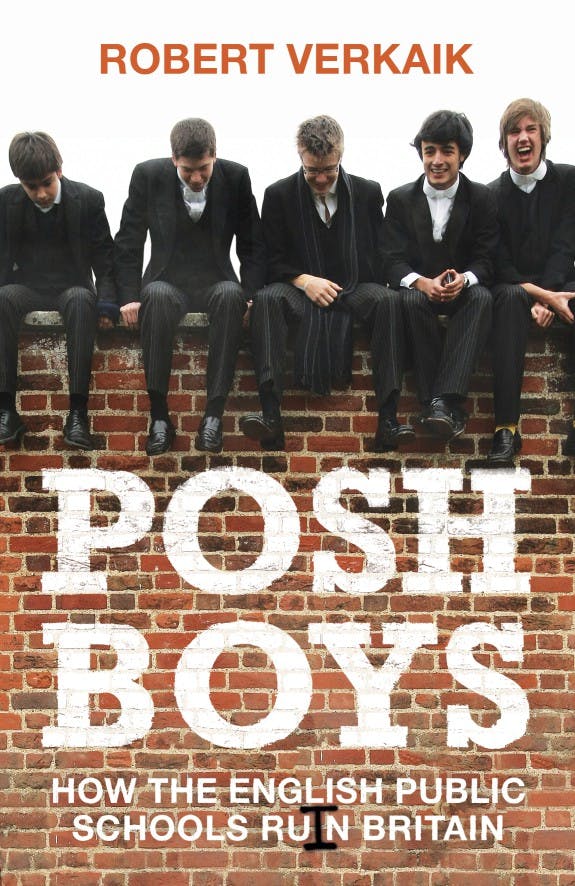

POSH BOYS: HOW THE ENGLISH PUBLIC SCHOOLS RUIN BRITAIN by Robert VerkaikOneworld Publications, 304 pp., $25.99

POSH BOYS: HOW THE ENGLISH PUBLIC SCHOOLS RUIN BRITAIN by Robert VerkaikOneworld Publications, 304 pp., $25.99Robert Verkaik’s new book Posh Boys is a detailed and damning history of the institutions that at once run and ruin Britain. The most venerable of the confusingly-named “public” schools were established in late medieval England to educate poor but talented boys in religion and classics. They continued to teach that curriculum long after their charitable purpose had faded, and by their golden age in the nineteenth century, the public schools’ main purpose was to groom upper-class boys to become the administrators of the British Empire. They instilled an “unshakeable confidence” and sense of superiority in their pupils, as members of the best class of the best nation in the world. In return, they demanded unswerving loyalty and a willing submission to a rigid hierarchy.

Bullying was not just endemic, it was structural, with younger boys acting as servants for older ones, carrying out menial tasks and enduring whatever punishments their teen overlords could dream up, in the knowledge that eventually they would get to mete it out themselves. They went on to demand similar submissiveness and loyalty from the native populations they were sent out to rule, having been taught to regard them as unruly children in need of discipline.

A taste for violence and an obsession with hierarchy also work quite well to prepare boys for the military, and to this day the vast majority of teenagers enrolled as cadets in Britain attend private schools. Verkaik points out, however, that the military ideology bred in the public schools is mostly vainglorious myth. The British won battles across the Empire in the 19th century because they had vastly superior weapons, not better tactics or leaders—and the legend that the Battle of Waterloo was won “on the playing fields of Eton” is “fatally undermined” by the detail that school had no playing fields at the time.

Critics of the public schools have argued instead that their obsession with militarism—absorbed bone-deep by generations of prime ministers and generals—has in fact more often than not goaded the country into war and prolonged the bloodshed, most ruinously during World War I. The British army, led by a Harrow graduate, simply reproduced civilian class hierarchies, installing public schoolboys as officers with command over hundreds of working-class men whose life experiences were as foreign to them as those of the African villagers their forefathers subjugated. A disproportionate number of these aristocratic boys, including the prime minister’s son, died in the fighting for the nihilistic, vaguely classical ethos that death in battle would be the most noble end to their lives.

Public schools continue to place a strong emphasis on violent sports—at many schools rugby, which was invented and much mythologized at the northern English school of the same name, is preferred, while Eton lays claim to the notorious “wall” game, a violent mass scramble that killed a boy in 1825. Historically, masters encouraged games and military drills, as a way of exhausting the body and beating out any dangerous tendencies like gentleness, kindness, and affection. But given their cultures of loyalty and secrecy, it’s hardly surprising that sexual abuse has been rampant in the public schools for centuries. In a pattern that mirrors similar cover-ups in religious communities, Verkaik writes, “children were either disbelieved or silenced” and “the teacher quietly moved on.” The stories of victims are currently engulfing many of the country’s most elite schools in scandal, with a pair of comprehensive independent inquiries underway that will make their findings known in 2020.

Would even the most damning revelations puncture the lingering mythology of the public schools? For generations, these schools have guaranteed exclusivity and loyalty through elaborate codes and rituals (which saturate English literature from Tom Brown’s Schooldays to Enid Blyton novels and Harry Potter,). Old Etonians are famed for identifying each other with the question, “Did you go to school?” as though there is only one school worthy of the name. Those strictly-controlled networks can sustain a graduate throughout his or her life, but in the short term, a parent’s investment pays off in improved chances of entrance to Oxford and Cambridge, or another top-tier university. Eton was established in 1440 as a feeder school to my own alma mater, King’s College, Cambridge—which prided itself, when I was there, on taking more state-school pupils than any other college, but still held places for choral scholars, often from Eton and other public schools (since not many comprehensives train their students in world-class choirs.)

Fee-paying schools educate 7 percent of British schoolchildren, but in 2016, 34 percent of Cambridge acceptances and 25 percent of Oxford places went to privately educated applicants—actually much lower numbers than in previous years, as both universities have tried to tackle their elitist image. Yet in Britain the professions—from politics to the military, law, journalism, and banking—all remain dominated by private school graduates. Access, a hand up the ladder, is what the schools sell. And it can have immeasurable value—ask Kate Middleton’s wealthy middle-class parents, who sent their daughter to the exclusive co-ed boarding school Marlborough College as a stepping stone to St. Andrew’s University, where she met and started to date a member of the royal family.

One weakness of Verkaik’s analysis is that it doesn’t really consider how the most traditional all-male schools like Eton differ from all-girls schools and co-ed schools. There is no doubt that girls in private schools, whether single sex or co-ed, benefit in similar ways from the improved chances of university access and the post-school network, but it’s still harder for professional women to accumulate wealth and power on a scale to match the entrenched advantages of their male counterparts (girls’ schools struggle a great deal more to attract alumnae donations, for example.)

One email even began with the phrase, “Confidential, please, so we aren’t accused of being a cartel.”Exclusivity and access have justified enormous hikes in private school fees in recent years, leading some to fear that fees are rising in a “bubble.” In 1990, annual boarding-school fees were less than £7,000 per year, they now hover around £40,000. At Eton, extras like uniforms, trips, supplies, and miscellaneous “donations” can run another £10,000 on top. It’s in the interest of all schools to keep pace. In 2001, two boys at Winchester College hacked their school’s private email system and exposed a price-fixing scheme aimed at ensuring that fees rose well above inflation across the sector. One email even began with the phrase, “Confidential, please, so we aren’t accused of being a cartel.”

Such behavior is all the more galling because public schools in the United Kingdom enjoy tax-exempt charitable status. Several governments, Tory and Labour, have attempted to reform the relationship between the schools and the state—either by taxing school fees, cutting off some state funding, or forcing the schools to behave more like charities, perhaps by educating some poor children for free. But in general, any discounts on fees tend to benefit middle-class, professional parents, who are the bottom-feeders of the ecosystem at a school like Eton. Genuinely poor children remain, for the most part, a purely theoretical species. In order to become need-blind in their admissions, the schools would need endowments similar to those held by the leading private American universities, and a fundraising infrastructure to match—something that might be in the reach of Eton and Harrow, with their oligarchs in the rolodex, but certainly does not look feasible for less prestigious schools.

The cozy relationship of public schools to the global super-rich has become increasingly apparent in recent years. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of wealthy Russian pupils at elite UK boarding schools more than tripled, and a group of Eton students made headlines when they were granted a private audience with Vladimir Putin. During the Cold War, the KGB notoriously recruited several public-school-educated British boys as spies and double agents, but Russia’s relationship with the status-symbol boarding schools today is far more open, visible, and lucrative, both to the schools themselves and the highly paid consultants who ease the admissions process.

UK private schools and colleges are attracting more and more of their fee income from wealthy overseas parents, but they are not compelled to report or investigate suspicious transactions, raising concerns that they could be targets of corruption or organized crime—in 2014 a prestigious Somerset boarding school was caught up in a global money-laundering investigation when it was discovered that a pupil’s fees had been paid via an illicit shell company. But Transparency International, the anti-corruption organization, has warned that it is not just money—the schools also have the power to whitewash the shadiest family reputation.

Despite the risks, the value of the school brand in a global marketplace is too high to pass up, and several English schools have established campuses in China, Russia, South Korea, Singapore, Qatar, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere, educating some 30,000 children of the rich and influential, in “an important expression of Britain’s own soft power.” At the same time, some foreign buyers have been disappointed by the quality of the product so expensively purchased. One German banker, who sent his children to Westminster school, cautioned his countrymen against sending their children to these bastions of excess and entitlement, where the education was no better than what children gained for free in Germany. Like France and many Scandinavian countries, Germany has barely any culture of private schooling beyond religious institutions. Why would you pay for something that ought to be your right as a citizen?

For Britain’s privately educated leaders, politics is a ladder to be climbed, and policy-making a game.That question leads to murkier, deeper waters: What is an education for? How can we know it’s good? There is plenty of historical evidence that public schools did not offer the best education: Their commitment to the classics and deliberate, disdainful neglect of the sciences during the nineteenth century meant that most of the figures whose innovations drove the Industrial Revolution were educated outside the system. More recently, the moral code that elevated “muscular Christianity” and its ethos of leadership seems to have dissolved, leaving pure muscle behind. Verkaik observes of the 46 boys in former Prime Minister David Cameron’s 1984 Eton house, only one could claim to have gone onto a career in public service: He became a schoolteacher, although eventually “returned to the private fold.” The others became politicians, bankers, journalists, entrepreneurs—professions where success rests on something that public schoolboys learn to excel at: public speaking, debate, the subtle art of blagging. These boys dominate British politics across parties: Labour leaders Tony Blair and current leftist hero Jeremy Corbyn both have public-school pedigrees.

For Britain’s privately educated leaders, politics is a ladder to be climbed, and policy-making a game. Never has this been clearer than in David Cameron’s colossal gamble on Brexit in the summer of 2016, when a referendum dominated by bad-faith messaging, data breaches, and campaign-finance violations triggered the UK’s limping exit from the European Union. It was not a cause for which the majority of citizens was seriously advocating. The only real victors so far have been those (often privately educated) financiers who made millions by betting on a massive drop in the value of the pound.

The ethos of the modern British private school is not the same now as it was in the days that molded the country’s current leaders. The turn against bullying and the emphasis on a well-rounded, pupil-centered education have penetrated even their forbidding ivy-covered walls. Still, Verkaik’s book is not a call for the reform of the schools, but for their abolition. Tweaking their tax status, or limiting the numbers of top-tier university places their pupils can earn, will not absolve the schools of the real damage they do to communities by encouraging their most privileged members to opt out.

Verkaik argues that “pushy” middle-class parents are needed to pull up the standards of struggling state schools, and that the presence of their “articulate, confident, able” children will help their less privileged peers. But this is a painfully one-sided view. As the American journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones has frequently pointed out in her work on school segregation—racial and socioeconomic—in the United States, the white, middle-class kids have just as much to gain from learning alongside children who are different from them. Difference challenges us, and so does community: It requires that we put ego aside and commit to values that transcend our individual tastes, wants, and needs. It may be uncomfortable, but difference is not harmful. The alternative is segregation, isolation, and a cripplingly narrow vision of success.

For the first time in American history, white men comprise a minority of Democratic candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives: The party has nominated 180 women and 133 people of color for the House’s 435 seats, according to Politico. “The numbers are even starker in the districts without Democratic incumbents,” Elena Schneider reported. “In the 125 districts where a Democratic incumbent is leaving office or a Republican seat is at risk of flipping...more than half the nominees (65) are women.” White male dominance in the House—and Senate—won’t end in November, but it appears to be on the wane.

This “year of the woman” isn’t limited to Congress. A record 14 women are competing in the 36 gubernatorial races being decided in November. Eleven of them are Democrats, and three of those would make history if they won their races, as Vox noted earlier this week: Georgia’s Stacey Abrams would become America’s first black woman governor; Vermont’s Christine Hallquist would become the first transgender governor; and Idaho’s Paulette Jordan would become the first Native American governor. In South Dakota, Republican Kristi Noem is likely to win her bid to become the state’s first female governor.

The latest evidence suggests that these candidates are up against greater odds than their counterparts running for Congress. As of Thursday, according to Politico’s women candidate tracker, half of all women running for the House and 42 percent of women running for Senate have won their primaries. But only 27 percent of women candidates for governor have accomplished the same. Some of that may have to do with greater competition for fewer seats: 61 women had declared campaigns for just 36 gubernatorial seats. But historical evidence bears out this truth: It’s extremely difficult for women to become governor.

There are only six female governors in office today, down from a peak of nine in 1994. There have been only 39 women governors in U.S. history, and 22 states have never had one at all, according to Rutgers University’s Center for American Women in Politics (CAWP). Voters didn’t elect a female governor in her own right until 1974, when Connecticut voters put Democrat Ella T. Grasso in office. Previously, three female governors had succeeded their husbands in office.

Jane Swift, a Republican and former acting governor of Massachusetts, explained what women are up against in running for the office. “If they think you’re nice, they think you can’t run their state, and if they think you can run their state, they worry you’re not nice,” she told The New York Times. The role of governor includes a ceremonial aspect, not unlike the role of president; the governor moves their family into a mansion, where they remain in the public eye for at least the next four years. If the governor is male, traditional notions about breadwinning husbands persist without challenge. A female governor, however, subverts those old ideas.

“The biggest challenge that women face when running for executive office is they really have to work twice as hard to prove that they’re qualified, because we know that voters are more accustomed to seeing women as part of a deliberative body like a legislature,” said Amanda Hunter, the communications director for the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, which has tracked every gubernatorial race with a female candidate since 1998.

“I think women, when they run to be the chief executive, still have a challenge, which is the stereotype about women not being tough enough, or strong enough, to be that final authority and to be the place where the buck stops,” said Debbie Walsh, CAWP’s director. (CAWP and the Barbara Lee Family Foundation run Genderwatch 2018, which monitors the campaigns of female candidates and analyzes gender’s influence on electoral outcomes.)

If a woman can break the gubernatorial glass ceiling, however, she might help smooth the way for future candidates. “For example, Molly Kelly won her primary in New Hampshire. And New Hampshire’s had two female governors, Governor Shaheen and Governor Hassan,” Hunter said. “And we’ve seen that trend with Arizona. They’ve had four women governors. Kansas has had two. Then of course Gretchen Whitmer won the primary in Michigan, and they had a female governor not terribly long time ago.”

Where men can rely on their credentials, women are more likely to win over voters by emphasizing personal experience and real-world achievements, either in state or local politics or in the business world, according to Hunter. The Barbara Lee Family Foundation’s research found that successful women candidates find ways to balance authenticity with likeability, but even if they do discover that balance, they can still face other institutional obstacles. “Although women now often regularly raise and spend money in their campaigns on par with their male opponents, women candidates still report being excluded from financial circles that include the wealthiest and best-connected donors,” the foundation concluded.

With so few female governors in office, and so many obstacles to increasing their numbers, any uptick seems welcome. But a victory for a woman candidate isn’t always a victory for the women she represents. Four of the nation’s six female governors are Republican, and are hostile to legal abortion and to LGBT rights. In 2017, Alabama’s Kay Ivey, who is up for reelection, signed a law allowing adoption agencies to refuse to place children with same sex couples. Iowa’s Kim Reynolds, who is also up for reelection, signed a May law banning abortions after a fetal heartbeat is detected. In New Mexico, Governor Susana Martinez opposed same-sex marriage prior to the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized the practice, and has stated opposition to abortion rights (though some anti-abortion activists believe she hasn’t expressed enough public support for restrictive abortion regulations).

South Dakota’s Kristi Noem and Hawaii’s Andria Tupola, the two Republican nominees seeking a first term, also oppose abortion rights. Tupola has even re-posted articles by Operation Rescue, an extremist anti-abortion group, on her official Facebook page, and Noem has repeatedly attacked abortion rights as a member of Congress. As The Honolulu Star-Advertiser reported in 2014, Tupola also helped lead protests against the governor’s call for a 2013 special legislative session to legalize same-sex marriage.

Walsh called 2018 “a bit of a breakthrough moment” for women running for governor, and that’s clearly true in general. There’s a record number of candidates, and Abrams, Jordan, and Hallquist could all make history—not just for the Democratic Party, but for the country. But it’s not as clear, in a case like Noem’s, that a breakthrough moment for female candidates would mean a breakthrough moment for all women. Would her victory help accustom South Dakota voters to the idea of a woman as the state’s chief executive? Or will she end up pushing policies that make it more difficult for other women to achieve what she has done? In some cases, an achievement for one woman creates quandaries for others.

No comments :

Post a Comment