Though USB Type-C is a universal charging and docking standard, Microsoft left this key connection off of its Surface Pro 6 and Surface Laptop 2.

Though USB Type-C is a universal charging and docking standard, Microsoft left this key connection off of its Surface Pro 6 and Surface Laptop 2.

There are a couple of bars from The Mile Long Opera that I can’t get out of my head. “Funny how a manicure / Changes everything,” the line goes, rising up and holding at a level note in the middle, before doing a hop step back down. Then the line is sung again, but with the word “nothing” instead of “everything.” The phrase repeats with other words replacing “manicure”—“heartbreak,” “no L Train,” “hope”—but the back and forth of “nothing” and “everything” keeps going.

Will The Mile Long Opera be everything that matters about public art—or nothing? The show officially opens on Wednesday and runs until October 7, up and down New York City’s High Line, a leafy 1.45 mile-long esplanade constructed on a former elevated railroad over Chelsea. (You can watch the opera online as well.) Its full title is The Mile Long Opera: A Biography of 7 O’clock. It’s a linear, interactive experience: You walk down the High Line, bracketed by singers from community choirs across New York. Every so often little groups surround you like a chamber ensemble.

The effect is extraordinary. It’s polyphony, but you, the listener, control what you hear. Curious about how the music melds with the music further down the park? Just keep walking. Captivated by a particular passage? Stay where you are. Dynamics in sound become dimensions in space. You’re so close to the singers that it’s awkward. Look them in the eye or look at your feet: It’s your choice.

The opera was conceived by architects from the firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (which designed the High Line in collaboration with James Corner Field Operations and Piet Oudolf), and composed by David Lang, with libretto by the poets Anne Carson and Claudia Rankine. It is an enormous endeavor, comprising a thousand singers. The performance starts at 7 p.m. each day and is a tribute to that time of the evening. Drawn from interviews with New Yorkers, there are stories about leaving work and walking home; complaints about how the streets are clogged with trash; tender lyrics about solitude and work and the city. It is a social opera, set in a social space.

The work and the setting, however, mesh uneasily. The High Line is not New York, at least not the New York represented by those everyday stories. In 2017, Robert Hammond, the executive director of the nonprofit Friends of the High Line, admitted that its creators “failed” to provide a genuine community space to the neighborhood. Its users are mostly tourists. They’re mostly white. Can an opera seeking to channel life in New York succeed when its stage is close to being democratic, but not quite?

Controversies often flock around public artworks, particularly those which invite regular people to participate in them. The work of Tino Sehgal, for example, exists in choreographed activities performed by people who are not the artist, including members of the public. His 2010 piece “This Progress” called for a series of guides at the Guggenheim to ask museum-goers about their ideas of progress, with the museum’s famous rotunda as a backdrop. Sehgal’s work scales down art from being an object outside of history to the little moment of human beings interacting.

When audience members play a key role in a work of art—as big public works invite them to do—something is being demanded of them. The Mile Long Opera is no different. It relies completely on your participation to exist. If I could somehow render onto the page those bars that are stuck in my head, it might give you a sense of what it felt like for a single moment to stand next to a woman who was singing the lines in a tremulous voice. But you would miss the seconds before and after that moment, when I was moving in and out of earshot, in and out of the sounds of the city itself: the other sounds of 7 o’clock.

Those who see the show this week will experience different weather conditions. On my night with the Mile Long Opera, a strong wind blew. It was a hot wind on a dark night, the kind of wind that feels like it’s carrying some significant change. The air rustled the grasses, with a few large raindrops passing through it. Cicadas rasped in rhythm, as they do. Sometimes I was beside a tree containing a single cicada, and at other times every cicada on the High Line melted into a background chorus. A whistle blew at a sports game down at Chelsea Piers; a motorcycle whined a sinister Doppler effect that worked into the harmony of the performance.

The High Line can feel isolated from the city, pedestaled and artificial, but that dark, sheltered stream of foot traffic also intersects with New York itself. Where you cross 26th Street the old New Yorker neon sign is visible out of the corner of your eye. A fire escape is so emphatically “Manhattan” that it looks like it came from the stage set for Rear Window. Zaha Hadid’s new welter of condos looms on the left like a big glowing cake, Diane Von Furstenburg’s polygonal penthouse attic is to your right.

The chorus was diverse, by age, gender, race, and language (including Japanese and Spanish). Both young women and elderly men sang, “I think about coffee cups a lot.” Different voices rose to prominence, depending on where you stood. Some people looked at the ground, trying just to hear, but others stood face to face with singers and stared them down. The variation in the voices is perhaps the key joy to the music. A man with a baritone boomed the words “Not just survival.” Nearby, a weaker voice engaged in a soft recitative. Isn’t this how the city is at 7 o’clock? On the subway or the street we tune in and out, to the low and to the loud.

In the penultimate section, the chorus walk with glowing bags as if returning from an errand. We used to know each other, they mourn. Where is the intimacy that we, dwellers in the big city, have lost? This is just one New Yorker’s feeling, and yet when a whole gang of people sing it, the feeling becomes something different—a collective emotion that transcends time and subjectivity.

Soon this music will be available for everybody to hear online. Its value as a work of public art, though, comes from the memory of those who participate in it. For me, it was as much the motorcycle-whine and hot night air as it was the harmony in a minor key, fading between phrases and melodies as I floated above the west side of Manhattan. The whole project, from the variable weather to the first-person voice of the libretto, suggested that the most important thing was how I felt at that moment, one little mind moving through a river of voices. In The Mile Long Opera, there are as many operas as there are listeners, because it changes according to your position in space and your frame of mind. It exists to the extent that one is tuning in. It’s funny how art can mean nothing, depending on whether or not you’re listening; funny how an opera can change everything.

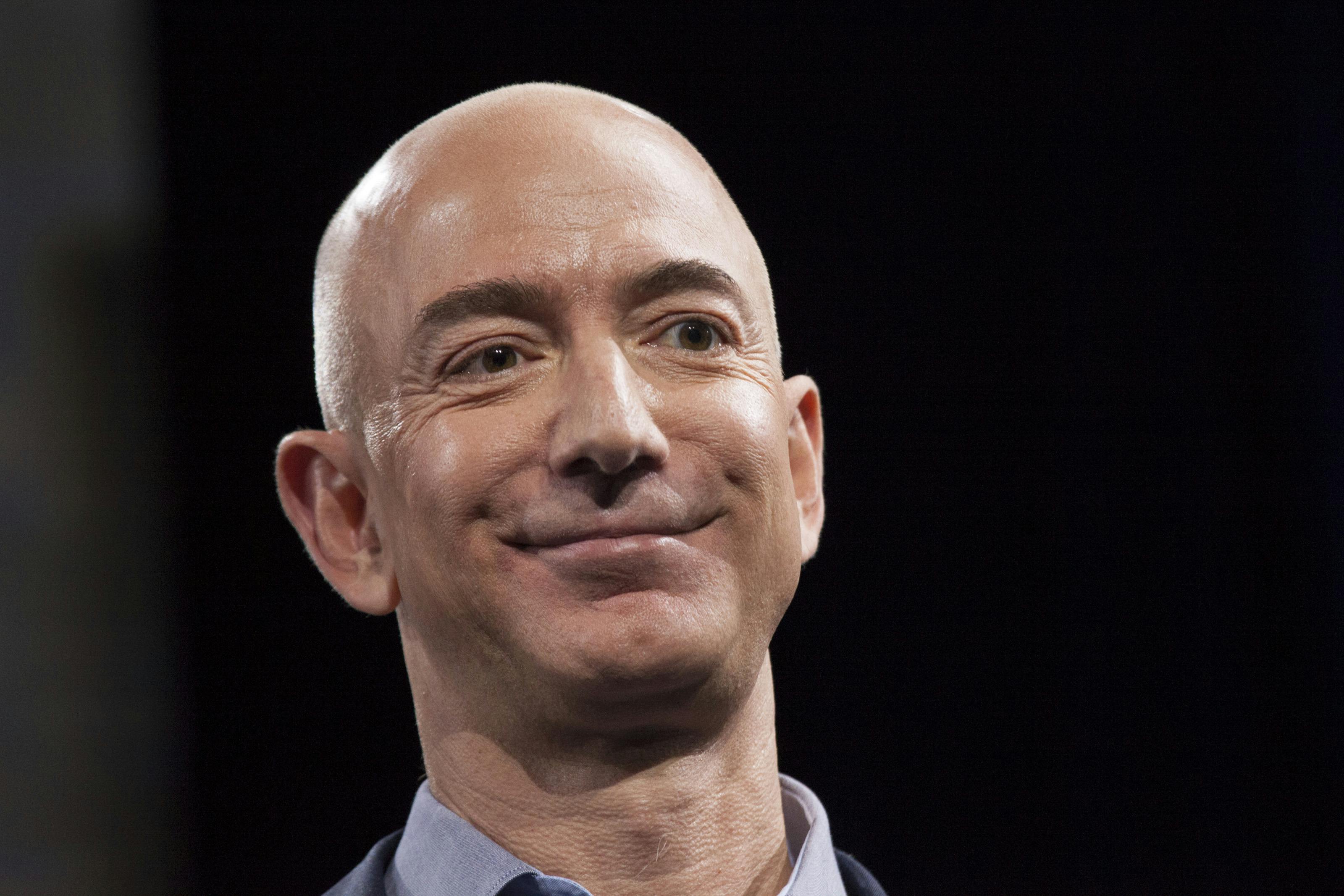

It’s not every day that Bernie Sanders praises the richest man alive. But on Tuesday, Sanders did exactly that, tweeting props to Jeff Bezos for Amazon’s decision to raise its minimum wage to $15, a move that will affect a quarter-million Amazon workers and 100,000 seasonal employees.

What Mr. Bezos has done today is not only enormously important for Amazon’s hundreds of thousands of employees, it could well be a shot heard around the world. I urge corporate leaders around the country to follow Mr. Bezos' lead. https://t.co/06wIAHunPq

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) October 2, 2018The friendship surely won’t last, given Bezos’s immense wealth and Sanders’s lefty politics, but it was nevertheless a stunning moment for Sanders, who has made Bezos the face of stark income inequality and America’s new Silicon Valley aristocracy. In September he even co-sponsored the Stop BEZOS Act, a bill that would tax corporations for every dollar of public assistance that their workers received. Amazon, for its part, released a rare public statement rebutting Sanders’s claims about the company’s well-documented mistreatment of its workers.

The Stop BEZOS bill was controversial—if enacted it would be impossible to enforce and would create widespread chaos—but its main purpose was to shame Amazon into improving its working conditions. Following Tuesday’s announcement, it’s a tactic that Sanders and other Democrats may use again when dealing with giant companies like Walmart and Apple.

But Amazon’s decision to raise its minimum wage was influenced by a number of other factors, and says a great deal about the political complexity of running an enormous (in this case, $1 trillion in market value) corporation. Like other companies, Amazon is very conscious of the political damage that can be done by being on the wrong side of certain issues. At the same time, taking safe stances can be a useful branding tool in creating an aura of corporate social responsibility. By raising its minimum wage to $15, Amazon is garnering the most political capital it can from taking a position that very likely would have been forced on it anyway.

For much of its existence, Amazon and Jeff Bezos have ruthlessly pursued cost-savings. The company skipped out on sales tax, to the detriment of states and small businesses; it targeted its weaker competitors in an effort to gain maximal market share (Bezos even told employees to hunt book publishers the way “cheetahs” pursue “sickly gazelles”); and it expanded by relying on cheap, often temporary labor, much of which was contracted out. There have been a slew of lengthy investigative reports about the horrible conditions in Amazon’s warehouses, where workers making minimum wage (or close to it) often are barred from taking bathroom breaks, labor in unsafe conditions, and are fired when they get injured.

In spite of this, Amazon enjoyed widespread bipartisan support for much of its rise, held up by business-friendly Republicans and tech-friendly Democrats as a sterling example of American ingenuity. Given the lack of any appetite for regulation on Capitol Hill, Amazon was happy to ignore its critics. But over the last few years, the environment has begun to change, with politicians—notably Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, along with some on the right—calling for greater regulation. In the fall of 2015, The New York Times published a report detailing Amazon’s brutal workplace culture and mistreatment of its white-collar workforce. The company, which had by then hired former Obama Press Secretary Jay Carney, pushed back aggressively against the piece, the first big sign that it was taking media coverage more seriously.

Amazon is as ambitious as ever. It recently became the second trillion dollar company in American history (the first was Apple). More Americans subscribe to Amazon Prime than regularly attend church. The company is producing movies and television, and pushing into the online advertising business. It is exploring artificial intelligence and health care. Its cloud computing wing may be losing its competitive edge, but remains insanely profitable. It owns Whole Foods, but its physical retail empire is really only beginning. And yet, despite the company’s unprecedented power, it is vulnerable in new ways. Like its competitors, Amazon is aware that the highly favorable political environment in which it was born is dissipating and may not return again.

There’s no doubt that the Stop BEZOS Act played a major role in the company’s decision to raise its minimum wage. The same goes for the media coverage of its treatment of low-wage workers. Amazon could shake off that kind of criticism a few years ago, but now it’s grist for legislators like Sanders who are casting billionaires like Bezos as the robber barons of the 21st century. “Count to ten,” Sanders tweeted earlier this year. “In those ten seconds, Jeff Bezos, the owner and founder of Amazon, just made more money than the median employee of Amazon makes in an entire year.” An earlier announcement that Bezos was donating $2 billion of his vast fortune resulted in eye rolls, thanks in part to the low pay being earned by Bezos’s employees. Shame is always a vital tactic in politics; with Stop BEZOS, Sanders and his co-sponsor Ro Khanna shamed Amazon into doing the right thing.

It’s no accident that Amazon settled on $15. Over the past four years, Fight for $15, a group advocating for a higher minimum wage, has won a host of victories in states and cities across the country. Through short strikes and a public relations push, Fight for $15 has also embraced shame as a tactic, leaving corporations with the choice of improving their working conditions or enduring long periods of bad press. The movement has pushed the minimum wage into the national conversation, and on Tuesday, Amazon decided it would rather have it as a friend than an enemy. One of the most important aspects of the company’s announcement was that it urged its rivals to follow suit—and pledged to spend resources to push the national minimum wage higher.

By raising the minimum wage, Amazon took an arrow out of the quiver of its critics. The next time the media comes knocking, the company is now able to point to something tangible that it has done for its workers. And it’s also a sound business decision. The labor market is very tight right now, particularly for low-wage workers. Amazon’s low-wage employees often work grueling jobs, often during the holidays. So it is incentivized to raise its wages.

There is a sense right now that this is a major development—that other companies will have to pony up more money for workers, too. But it remains to be seen whether that will happen. Moreover, it’s not yet clear how many people will benefit at Amazon itself. The company relies heavily on people who aren’t technically employees—who are employed by contractors, for instance. Much of the work it does is automated, or will be automated in the near future. Amazon’s market power is still enormous and bad for wage growth broadly. Still, by raising its minimum wage to $15, it did the right thing—if not necessarily for the right reasons.

A tourist treading the streets of ancient Pompeii might well notice, viewing the buildings still extant there, that Roman dwellings, lacking in windows of any kind, were oriented entirely inward, toward a central courtyard surrounded by individual rooms. This architecture suggests how highly the ancient Romans must have valued the privacy of family life, its separation from the hurly-burly of the social world outside.

But the Romans equally prized the opposite realm, the res publica, or “public thing,” where matters of concern to the community as a whole were addressed: the realm of politics. This is the origin of the term republic, and of republican political philosophy, which the Romans inherited from their Athenian predecessors. Aristotle defined the human being as the political animal, and republican practice requires the active involvement of citizens in political life. A republic is, above all, a self-governing community.

The philosophy of liberalism emerged much later, during the waning of the Middle Ages, when individuals began to see themselves as individuals, in the modern sense, and to engage in freeing themselves as such from various forms of constriction and oppression—monarchial rule in political realms, feudal control of the economy, the Roman Church’s monopoly over the intellectual sphere—that had bedeviled their forebears over a millennium. The forms of freedom sought by liberal philosophers of the early modern age mostly involved what the British political thinker Isaiah Berlin characterized as negative liberty: principles of freedom stated in the negative, such as, “Congress shall pass no law respecting the establishment of a religion.” Republicanism, on the other hand, represents perhaps the best variety of positive liberty: It not only encourages citizens to engage in political life, it obliges them to do so; in its view, only a self-governing polity can be truly free.

To what extent are liberalism and republicanism compatible with each other? This is an important question. Contrary to what Americans tend to believe these days, the United States was founded at least as much on republican principles as it was on the vaunted liberalism of John Locke, if not more so. (Consider the fact that the Lockean Bill of Rights was appended to the Constitution later, almost as an afterthought.) My view is that they are compatible—that, in fact, they can even complement each other, just so long as they respect each other’s proper sphere of action. Republicanism goes awry when it seeks to interfere with individual liberty in an unnecessary, counterproductive way, as the predominately republican Progressive Movement did in the fiasco of Prohibition. Liberalism, on the other hand, undermines the democratic political order it depends on when it takes its central value of “negative” individual freedom to the point where it compromises effective self-government.

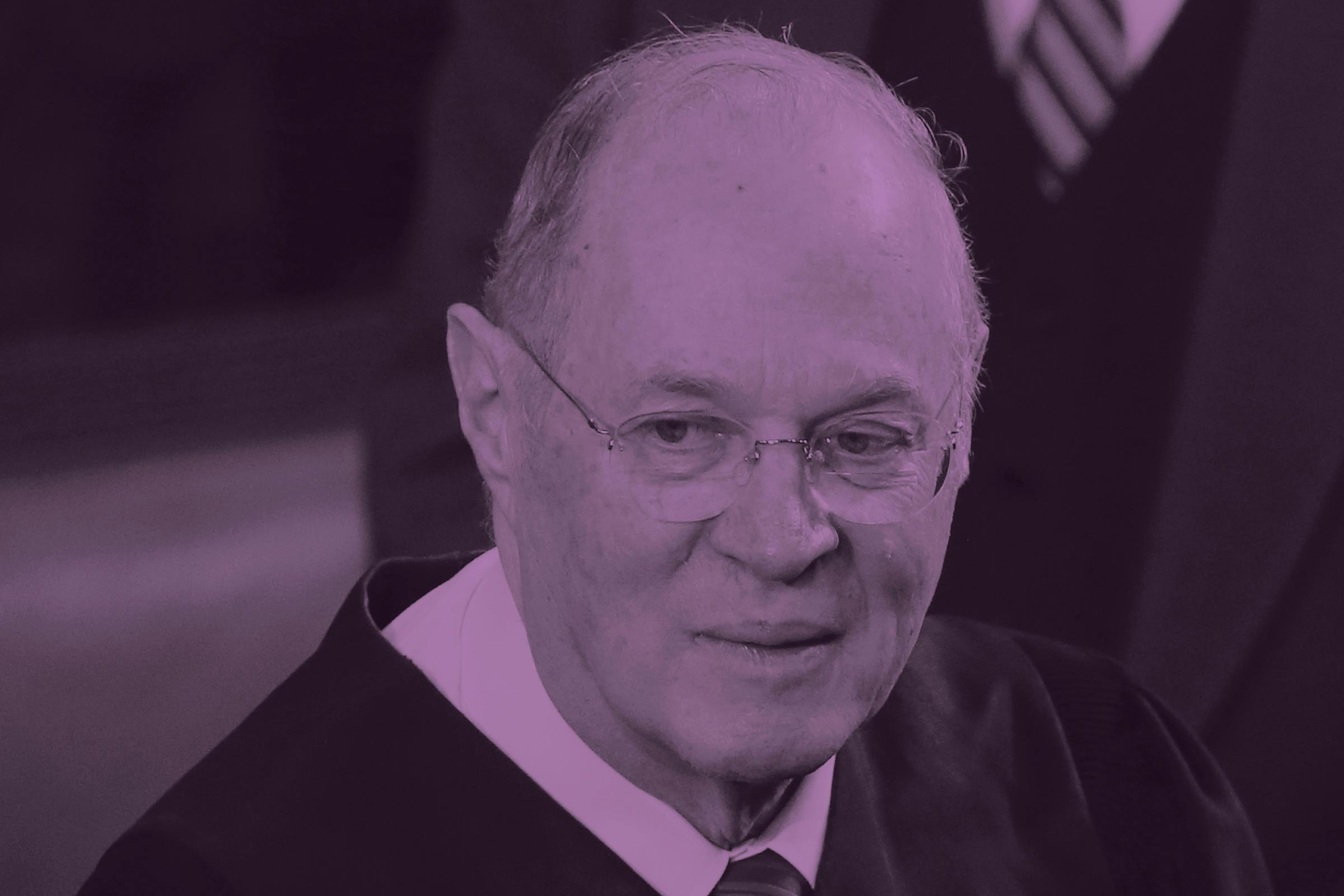

The extremely consequential jurisprudence of former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy is instructive in this latter regard. When Kennedy has upheld the freedom of individuals to conduct their sexual lives as they wish in the privacy of the bedroom, or the right of people to marry the person of their choice, regardless of gender, liberals have applauded him. Yet when he’s applied the same standard of maximizing individual freedom to the area of political campaign finance—authorizing the ability of wealthy individuals and powerful corporations (defined as individuals) to inject as much money as they want into a particular political race by means of so-called “independent” expenditures (or, in the case of wealthy individual candidates, directly into the coffers of their own campaigns)—liberals have been horrified. But what exactly is the difference between these two kinds of circumstance?

In the first, we’re metaphorically in the Roman villa, turned away from the outside world, absorbed in the realm of private existence. But in the second, we’re fully out in the public square— the forum—where the sanctity of the res publica is at stake. It’s the communal, republican standard of the public interest that applies here, not that of egoistic liberalism. “The Framers had their minds trained on a threat to republican self-government that this Court has lost sight of,” former Justice John Paul Stevens chided the majority in his dissent from Kennedy’s Citizens United opinion. “Starting today, corporations with large war chests to deploy on electioneering may find democratically elected bodies becoming much more attuned to their interests.”

As if to illustrate Stevens’s point, directly following the Citizens United decision, the Koch brothers deployed their vast, fossil-fuel–based wealth to turn virtually the entire Republican Party—which had once been of mixed views on the subject—against all efforts to confront global warming. They accomplished this by running their own chosen candidates against any and all apostate dissenters.

Exactly what danger does this kind of political blackmail pose to democratic self-government? “The predictable result,” Stevens wrote, quoting from a previous decision that Citizens United overturned, “is cynicism and disenchantment: an increased perception that large spenders ‘call the tune’ and a reduced ‘willingness of voters to take part in the democratic process.’” The predictable result is the diminishment of the American citizenry as a self-governing community.

No comments :

Post a Comment