Stumping for Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams last week, former President Barack Obama made the case that Tuesday’s midterms were an existential test for the country. The midterms “may be the most important election of our lifetime,” the former president said. “The character of our country is on the ballot.” On Monday, he returned to that message in a series of tweets:

When you vote, you have the power to make it easier for a student to afford college, and harder for a disturbed person to shoot up a classroom. When you vote, you have the power to make sure a family keeps its health insurance.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) November 5, 2018Obama is right—to an extent. Tuesday’s election is the country’s first real opportunity to rebuke a president who has repeatedly abused his office and a party that has deliberately sabotaged the health care of millions, damaged the rule of law, redistributed wealth to the richest Americans, and caused significant damage to long-standing diplomatic relationships. Rejecting Trump and Trumpism, especially given the racist tenor of the GOP’s midterms push, is important, especially at the state level, where Republican governors and legislatures have trampled on voting rights.

While the character of the country may be on the ballot, though, the character of its politics aren’t changing any time soon. Sweeping Democratic victories on Tuesday—especially if the party retakes both chambers of Congress—will lead to positive steps, including overdue House oversight investigations and, if they win the Senate, meaningful checks on the president’s power and influence over both the judiciary and various cabinet positions, particularly the Justice Department. But it will also lead to a fierce counter-reaction from the president and his allies—and a further embrace of racist fear-mongering over issues like the migrant caravan. If Republicans preserve their control of Congress, meanwhile, it would be devastating, leading to the end of the Mueller investigation and perhaps the repeal of Obamacare.

No matter what happens on Tuesday, then, the state of American politics can only get worse.

A blue wave on Tuesday would undoubtedly be a blow to the president and his party. If the Democrats take the House, but not the Senate—the likeliest outcome—they could still do an enormous amount of damage, ensnaring him in investigations into his finances, behavior, and governance for years to come. If they take the Senate as well, they could constrain his power by refusing to confirm judges—as Jeff Flake threatened to do over tariffs—and executive branch appointees.

These would be reasonable, overdue actions. But they will be met with a furious response. If the Democrats take the House and not the Senate, would-be Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Trump will spend the next two years locking horns over subpoena after subpoena. The Senate will respond by acting as a shield, with the same Republican lawmakers who stepped in to protect Brett Kavanaugh—Chuck Grassley, John Cornyn, and Lindsey Graham—doing their best to distract from or downplay his scandals. This particular dynamic likely wouldn’t change even if Democrats prevail take the Senate.

Theoretically, divided government could lead to compromise, since Trump would need Democrats to pass legislation. With 2020 approaching, the thinking goes, he would be incentivized to make deals that show that he can get things done (on infrastructure, for instance). But Trump has shown no interest in this kind of politics. Yes, he has flirted with bipartisanship in the past, but has always ultimately demurred, either due to pressure from aides and donors or from a preternatural devotion to his base. When pressed, Trump has eschewed dealmaking and calls for unity and doubled down on attacks on the media and his Democratic opposition.

Over the last two years, despite controlling Washington, Republicans have done little with their power. Their only major legislative achievement was the $1.5 trillion tax cut, largely benefiting corporations and the wealthy, which appears to represent the entirety of the party’s ideas. The GOP’s policy apathy has become apparent over the last two months, as candidates across the country have embraced the president’s ethno-nationalism and racist immigration policy. With defeat looming, the GOP sees fear-mongering as the only way to get their aging white base to the polls—a strategy that worked two years ago. Expect Republicans to employ these tactics even in defeat.

In fact, they may employ them especially if they lose. The most likely Republicans to lose in Tuesday’s midterms are the most moderate members of Congress, those in suburban districts won by Hillary Clinton in 2016. “That means that your ordinary Freedom Caucus member is going to get reelected even in a blue wave, while the vulnerable members are the more moderate ones who represent swing districts,” Paul Waldman wrote in The Washington Post on Monday. “This will produce a somewhat ironic result in the next Congress: The bigger the blue wave, the more conservative the Republican caucus will end up being when it’s over, and the less equipped the GOP will be to run a different kind of campaign in 2020.”

The GOP’s embrace of a migrant caravan that is hundreds of miles away is instructive. The caravan poses no national security risk, but Republicans and their allies have made all kinds of wild insinuations, suggesting it is full of gang members, terrorists, and lepers. Though some Republicans worry that the caravan will cost the party voters, thus far it appears to be a successful get-out-the-vote strategy as well as a distraction from more pressing issues that don’t reflect well on the president (from Saudi Arabia’s carnage to yet more administration scandals). As the walls close in on Trump, the racist appeals will only increase.

This is true even with the best possible scenario on Tuesday, in which Democrats win both chambers of Congress. If Republicans were to remain fully in power, the result would be infinitely worse. While it’s unclear how much the GOP could do with a narrow majority, it would be a major blow to Obamacare, sensible immigration policy, and the Russia investigation. A victory in Trump’s first midterms, in defiance of historical patterns, would also validate the party’s devotion to racially charged appeals and voter suppression, and they would double down on both.

Republicans opened the Pandora’s Box that led to Trump’s presidency years ago. They have become, as the midterm campaign has made clear, a party whose core identity is based around xenophobia and white grievance. Democratic victories on Tuesday may set in motion the end of Trump’s presidency; they would certainly provide a level of oversight that has been sorely lacking for the past two years. And the Republicans would respond by heeding their worst instincts. What happens in 2020 is anyone’s guess, but the final scene of Reservoir Dogs comes to mind.

Colorado voters won’t just be choosing elected officials when they go to the polls on Tuesday. They’ll be deciding, via a controversial ballot initiative, the future of the oil and gas industry in the state. Proposition 112 would require all new oil and gas development to be at least 2,500 feet from inhabited buildings and other “vulnerable areas” where it poses a risk to humans and the environment. According to one estimate, such restrictions could render 95 percent of land in the top energy-producing counties off limits to new drilling. That could really harm the economy, opponents say, since Colorado ranks among the country’s top oil and gas producers.

But Proposition 112 also could harm Colorado’s status as a swing state, or so the industry implies. To them, the measure—which would impact both traditional drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking—is not so much an attempt to protect public health, but, as The New York Times put it, “a liberal effort to drive a working-class industry—and its conservative employees—out of the state for good.” As one worker told the paper, “The people that oppose this industry, they treat us as if we’re really evil. They want to ban oil and gas and chase us out of this state.”

Proponents insist that’s not the goal. “Our only concern is that massive toxic industrial drilling is currently happening 500 feet from our homes, and 1000 feet from our schools,” said Anne Lee Foster, a spokesperson for the environmental group Colorado Rising. She also argued there would still be plenty of work to go around if it passed. “There’s 55,000 active wells in the state that the proposition does not apply to at all,” she said.

Supporters do, however, see Proposition 112 as “a chance to put a progressive stamp on a purple state,” according to the Times. And the timing would certainly be good to make such a mark, said Scott Adler, who chairs the political science department at University of Colorado Boulder. Though Colorado is split in thirds among Republicans, Democrats and independents, he said, “We’re certainly going more blue than red in recent years.”

But would passing an anti-drilling measure such as Proposition 112 really drive conservatives out Colorado, ushering in a reliably blue Colorado?

State political observers roundly laugh at the suggestion. For one, Adler said, the economic impacts probably won’t be as severe as opponents claim. “There are lots of claims about what [Proposition 112] going to do,” Adler said. “But the idea that it would end drilling completely seems a bit far fetched.” Tom Cronin, a retired Colorado College professor who authored a book on Colorado politics, agreed. While some rural areas will certainly be negatively affected, he said, “The impact on the economy has been exaggerated.”

“I think this suggestion that conservatives might flee Colorado over 112 is silly,” said Diane Carman, a former veteran columnist for the Denver Post. “The only way that would be true is if the conservatives heavily invested in oil and gas development in Colorado are unwilling to adapt to new rules and itching to leave anyway.” It will certainly be more expensive to adapt to Proposition 112—to comply with the setback rule, companies will have to drill further horizontally underground to reach oil and gas reserves—but it won’t be impossible.

Even if conservative Coloradans do lose their oil jobs, Cronin still doesn’t think they’ll leave the state en masse. After all, he said, when Colorado’s Democratic Governor John Hickenlooper moved to the state in 1981, he was a geologist for an oil company—and immediately got laid off. “Instead of leaving and going back home, he founded another business,” Cronin said. “He’s now got 19 restaurants and beer pubs across the country.”

Polling shows voters almost evenly split on Proposition 112 heading into Election Day. If the measure fails, it will be a huge victory for the oil and gas industry, which spent more than $30 million trying to defeat it. If the initiative passes, it will be a win for public health and environmental advocates who want to keep drilling away from their communities. What it won’t be is a referendum on conservatism in Colorado.

“We’ve been consistent for 30 years now as to party registration figures, and this is despite the fact that millions of people have moved here,” he said. “Colorado is purple. I think it’s going to be purple for a while.”

At a small jail outside San Salvador, Brother David Borja lifted his sunglasses to talk a guard into letting us inside. The cell, originally intended for temporary holding, smelled of sweat and urine. In the center was a roughly ten-by-ten-foot cage, and inside it, a tangle of limbs and hammocks.

At the sight of Borja, a street preacher from the Baptist Biblical Tabernacle “Friends of Israel” church, bare-chested, tattooed young men began crawling down from the hammocks and pulling on T-shirts.

As Borja started to pray, the men crossed themselves and bowed their heads. A few cried silently; others testified, “Truth.” One stuck his hand out of the bars. He held a bracelet, woven in a flower pattern from colorful plastic bags. Soon, a dozen held out bracelets. Borja collected them without pausing.

Borja closed his Bible and banged on the door, explaining that the bracelets were gifts for street children. As the guard latched the thick steel behind us, we could still hear the men’s applause, and pleas for the pastor to pray for them to be saved.

Founded in 1977, the Baptist Biblical Tabernacle “Friends of Israel” church, known as “Taber,” is now believed to be El Salvador’s largest church. Taber claims a congregation of more than 40,000, with millions of converts and more than 500 churches across the country. The megachurch also owns a handful of TV and radio stations and newspapers, extending its reach. In 1950, El Salvador was around 99 percent Catholic, but Protestantism has shot up since the 1970s, with 40 percent of adults today identifying as Protestant.

That makes Taber one of the most influential institutions in a country otherwise dominated by gangs.

El Salvador’s gang problem is American-made. From 1980 to 1992, Washington poured billions into the country, roughly the size of Massachusetts, backing right-wing military oligarchs battling leftist revolutionaries. The conflict killed 75,000 people, and tens of thousands more fled north. In Los Angeles, Salvadoran immigrants and refugees formed a street gang called MS-13, and began joining rival Barrio 18, a Mexican gang. President Bill Clinton signed a law fast-tracking deportations, and between 2001 and 2010, the United States deported more than 40,000 convicts back to El Salvador, exporting the gangs. Amid the war-tarnished ultra-conservative Catholic clergy and military, and the decentralized, barrio-based Evangelical churches, the gangs thrived.

El Salvador’s gang problem is American-made.Today, MS-13 is Central America’s largest gang, having built a transnational brand on brutal violence; one motto is “rape, control, kill.” MS-13 also provides U.S. President Donald Trump with a convenient bogeyman to justify a broader immigration crackdown in the name of protecting the homeland. “When we have an ‘infestation’ of MS-13 GANGS in certain parts of our country, who do we send to get them out? ICE!” Trump tweeted in July, referring to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—and the upcoming November midterms: “They are tougher and smarter than these rough criminal elelments [sic] that bad immigration laws allow into our country. Dems do not appreciate the great job they do! Nov.”

On October 15, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that MS-13 poses a more serious threat to the United States than any designated transnational crime group—even Mexican cartels and terrorist organizations. In reality, while El Salvador’s defense minister has claimed that some 500,000 Salvadorans are involved in gang activity at home, with roughly 60,000 active gang members in a total population of 6.5 million, U.S. authorities have estimated for more than a decade that MS-13’s American membership has remained at about 10,000 members, less than 1 percent of approximately 1.4 million gang members nationwide. There’s little indication that Salvadorans fleeing gang violence have increased MS-13’s numbers north of the border. Still, Trump’s apocalyptic rhetoric has given Salvadoran street gangs’ vicious reputation a global boost.

According to experts, one of the gangs’ golden rules is that members can never leave with their lives. But in the past few years, there’s been a fascinating development: Gang bosses are increasingly granting those under their command desistance—a status change from “active” to “calmado,” meaning “calmed down”—if they convert to evangelicalism. At El Salvador’s San Francisco Gotera prison, about 1,000 ex-gang members have become evangelicals, nearly all of the overcrowded prison’s occupants.

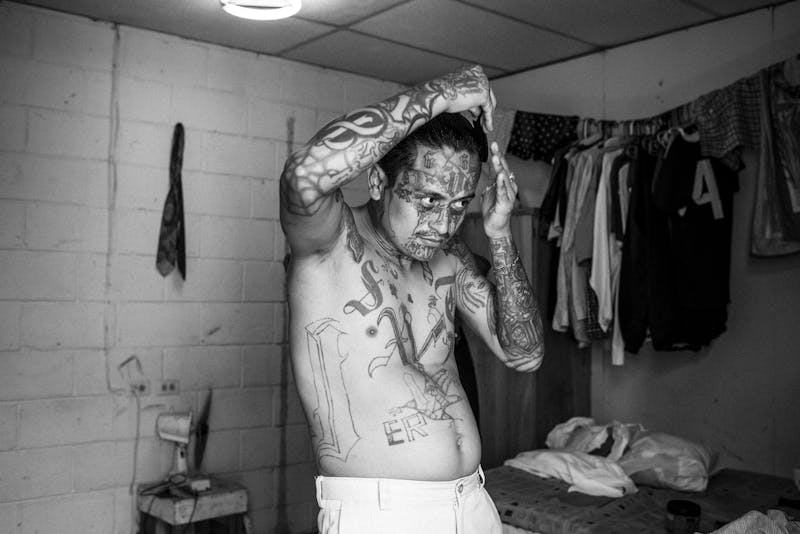

A worshipper tattooed with his former gang’s name, Barrio 18, on his skull.

A worshipper tattooed with his former gang’s name, Barrio 18, on his skull.The phenomenon can also be seen outside, at smaller Pentecostal parishes such as Ebenezer, whose ministry to gang members, The Final Trumpet, is known for speaking in tongues. Newfound-religious who stray from the righteous path, however—whether by drinking, doing drugs, beating their wives or girlfriends, or not attending church—can face deadly consequences from their former compatriots.

It’s an open, urgent question whether evangelical megachurches like Taber can use their influence to bring peace to El Salvador—or whether this is just one more union of political convenience that’s doomed to combust.

“This is a powerful book,” said Edgar López Bertrand Jr., raising a Bible at Taber’s massive headquarters in San Salvador.

López Bertrand, his office full of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and Harley-Davidson paraphernalia, has formally headed the megachurch since late 2017, when his father, Edgar López Bertrand Sr., died. Just after his takeover, El Salvador’s police chief announced that homicides had dropped 25 percent from 2016. Both the gangs and government take credit for the continued decrease in the national homicide rate, but it’s also vindicating for pastors like López Bertrand, better known as Toby Jr., who have put their credibility on the line by supporting gang rehabilitation.

“Churches have huge opportunity and power to change the national narrative from ‘kill them all’ to ‘we need a peace process,’” said Noah Bullock, executive director of Cristosal, an El Salvador-based human-rights nonprofit. “But there’s a lot of political risk.”

Among the rules that converted prisoners painted on the wall: “2. Respect and obey the ecclesiastic and civil authorities”.

Among the rules that converted prisoners painted on the wall: “2. Respect and obey the ecclesiastic and civil authorities”.The stakes for gang outreach are rising ahead of El Salvador’s 2019 presidential election, as the gangs face a renewed offensive from the combined forces of San Salvador’s security state and President Trump, who has prioritized the war on gangs at the expense of other aid. Both the left-leaning Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, FMLN, and the opposition party, the conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance, ARENA, have again endorsed gang crackdown as their security strategy, a policy largely indistinguishable and unchanged through two decades of elections.

In 2003, the ARENA government launched mano dura, an “iron-fist” approach imitating the American anti-gang strategy. After FMLN won the presidency for the first time in 2009, even the party’s guerillas-turned-politicians continued the militarized response. In overcrowded prisons, the gangs established control and consolidated power. Homicides continued to rise.

“The challenge for the two main parties is which can present itself as the tougher on crime,” says Jose Miguel Cruz, director of research at Florida International University’s Latin American and Caribbean Center. “That is their race to the bottom.”

Yet as the February presidential election looms, both FMLN and ARENA have largely evaded the gang issue, perhaps responding to voters’ apparent disillusionment with corruption and payoffs to the very criminal groups they rail against. In March legislative and municipal elections, 70 percent of voters defaced their ballots or stayed home rather than vote for either FMLN or ARENA, indicating that for the first time in decades, they’re looking for a third way. Former San Salvador Mayor Nayib Bukele, an anti-establishment, millionaire millennial and 2019 front-runner, backed the March boycott, although voters may not have needed the encouragement: Murders are on pace to average ten per day in 2018, nearly 80 percent of Salvadorans believe state security policies are ineffective, nearly 65 percent say police are violating human rights, and confidence in elections is at its lowest point in decades.

The Salvadoran political establishment’s hardline approach to gangs is supported by the U.S. government, which opposed gang negotiations even under President Obama, but has become a still stronger force against compromise under the Trump administration. In the past two years, the U.S. has deported thousands of Salvadorans, providing both new recruits and new targets for the gangs. The Trump administration has also threatened steep cuts in funding to El Salvador and other countries unless they do more to go after purported gang members, and threatened to choke off aid altogether unless they stop certain migrants. Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, served as a “get-tough” security consultant to the Salvadoran government in 2015, and his chief of staff, John Kelly, formerly head of U.S. Southern Command, has long advocated for more support to “professionalize” Central American security forces, despite evidence of human rights violations.

Roberto is prepares himself before receiving a diploma certifying his participation in the Eber Ezer Church and his commitment to change. Tattoos on the face and body can restrict former gang members’ options for a new life.

Roberto is prepares himself before receiving a diploma certifying his participation in the Eber Ezer Church and his commitment to change. Tattoos on the face and body can restrict former gang members’ options for a new life.All of this could end up empowering both El Salvador’s Evangelical movement and its criminal groups, which cater to poor and oppressed Salvadorans, including those fleeing to, and deported from, the United States. But whether the churches can use their increasing power to stabilize the country is far from clear. As Taber’s own history shows, not every attempt to spur negotiation has produced progress toward peace.

As civil war erupted in El Salvador in the 1980s, Toby Jr. was working at a Miami McDonald’s and racing motorcycles. Now forty-nine with a salt-and-pepper goatee, he still speaks English like a Miami teen, favoring “like” and “Can you imagine?”

His father was ordained in 1975 at Tennessee Temple University, then brought his family back to El Salvador to found his own congregation. But at 17, a rebellious Toby Jr. left for Florida to join his U.S.-citizen sister and mother.

By the time peace accords were signed and the prodigal son returned, Taber’s empire extended to a Bible academy, an orphanage, a rehab center, soup kitchens, and deportee services. With tattoos, piercings, boots and cargo pants, Toby Jr. publicly butted heads with his more conservative father, making no secret of his impatience for him to step aside and turn Taber’s empire over to a younger, more forward-thinking leader. When he died, the legislature held a moment of silence, and Toby Jr. inherited more than 30 ministries and 500 pastors.

I asked Toby Jr. how he felt about Trump’s attitude toward El Salvador and Latino immigrants. (Trump began his presidency talking about “bad hombres,” and “criminals,” and later moved on to talk of “shithole countries” and “animals.”)

“We’re

always blaming Mr. Trump,” Toby Jr. said. “But I always tell them, ‘The God the

Americans have is the same God the Salvadorans have. Now what is the

difference? You’re making the wrong choices.’”

Years before his father’s death, Toby Jr. began cultivating his own following—and invited controversy for giving gang leaders a platform at Taber.

In 2012, FMLN President Mauricio Funes privately gave his defense minister approval to pursue a truce with the gangs. Raúl Mijango, a former-guerilla congressman, and Fabio Colindres, a right-leaning Catholic bishop, became the primary negotiators. Under the deal, MS-13 and two Barrio 18 factions would lower homicides, and the government would transfer their leaders from maximum-security to lower-level prisons where they could enforce the truce.

Enter Toby Jr. A year into talks, as Toby Sr. was recovering from a stroke, his rising celebrity pastor son stunned Salvadorans by hosting incarcerated leaders from MS-13 and Barrio 18 before 7,000 congregants at Taber’s main church, as well as a national-TV audience. Under high security but without handcuffs, they sat next to each other in slacks and shiny shoes.

“They’d kill each other in a heartbeat! And I sat them down in church with a Bible,” Toby Jr. recounted.

In

the Taber interview with Toby Jr., the gang bosses told voters to boycott

candidates who opposed negotiation with the gangs. Afterward, they returned to

jail. Today, Toby Jr. insists that cabinet officials asked him to invite the

pair. If they did, they clearly didn’t anticipate the outrage from a

public long terrorized by gangs. After the event, the chief of prisons was promptly

dismissed, and as a backlash began in the polls, presidential hopefuls quickly

disavowed any deal with such criminals.

“Guess who got stuck with all the scandal? Me,” Toby Jr. said, insisting of the gang leaders, “I didn’t wash their feet, I didn’t give them Communion, I didn’t kiss them. They were just using us.”

As the truce’s prison transfers began, President Funes denied any quid-pro-quo, while the Catholic hierarchy declared its opposition, and the U.S. Treasury, which designated MS-13 a transnational criminal organization, added MS-13 leaders to its “kingpin” list. Subsequent reports and court testimony revealed that the incarcerated truce-participating gang leaders received everything from fried chicken and flat screen TVs to exotic dancers. Then evidence emerged that both FMLN and ARENA pledged millions of dollars to gang higher-ups to secure votes for the 2014 presidential election.

Still, the truce yielded a miracle: The homicide rate dropped by half. In 2015, when the truce collapsed, homicides spiked to a record 103 per 100,000 Salvadorans.

After FMLN barely held on to executive office amid the continued furor over the truce, newly-elected President Salvador Sánchez Cerén sought to distance himself from any association with negotiation, declaring a state of emergency in the prisons, deploying the military, and inviting extrajudicial killings of suspected gang members. The Supreme Court designated gangs and any collaborators as terrorists, and prosecutors charged dozens involved with the truce with crimes, including former President Funes.

Ahead of the 2019 contest, homicides have continued to drop from their 2015 high, but they remain among the highest in the world, and public confidence has tanked. FMLN is touting progress—but so are the gangs. MS-13 and the two main factions of Barrio 18 responded to Sánchez Cerén’s fervent crackdown by announcing a truce between themselves, independent of the state. The government can’t eliminate the gangs, a bandana-masked spokesman said, because they have the power “to destroy the country’s political establishment.”

In reality, even those claiming to offer a new path—the “anti-establishment” Bukele, for example—realize the necessity of bargaining with the gangs. Despite Bukele’s criticism of FMLN and ARENA for corrupt ties to criminal groups, his administration also made pacts with the gangs to secure projects while he was mayor, investigative site El Faro reported in June.

This is the legacy of the truce: Whatever Trump’s threats, the Salvadoran public, politicians, pastors and pandilleros all know that the road to the country’s salvation runs through gang turf.

A map showing the region of San Vincente, El Salvador, with pins marking 352 people who were reported to have disappeared, presumably from gang activity in 2016.

A map showing the region of San Vincente, El Salvador, with pins marking 352 people who were reported to have disappeared, presumably from gang activity in 2016.In the crowded cafeteria at Taber’s headquarters, Charlie and Manuel, who work as janitors at the megachurch six days a week, quietly told me they’d both come from gang life. Charlie had joined when he was just 11, and each served several stints in El Salvador’s overcrowded prisons.

“Daddy, this is the first birthday you’re here with me,” Charlie’s daughter told him on her ninth birthday. At that, he decided to leave the gang and turn to God, he said.

“Daddy, this is the first birthday you’re here with me,” Charlie’s daughter told him on her ninth birthday.Both asked that only their first names be used, for protection against reprisal from the gangs and the police. They’re only two of scores of gang converts as desistance continues to spread across El Salvador, but they remain vulnerable.

For a 2017 State Department report, Cruz interviewed nearly 1,200 current and former Salvadoran gang members. Roughly 60 percent said they’d gotten out or were getting out, and almost all said church was the best way. But whether conversion is sustainable is less clear.

“You need the country to create secular opportunities for its young people,” Cruz said—a view echoed by many experts.

Salvadoran and American officials believe gangs are using the Evangelical church as a front to grow their political capital. The reverse could also be true. “The cynical view is they [evangelicals] are getting involved in conversion of gang members in order to not only get political power, but also economic power,” Cruz said.

Increasingly aggressive police actions against the gangs have ensnared many civilians, even pastors—evidence some see as an important caveat to the hope placed in the Evangelical church. In a 2016 operation, authorities issued more than 100 warrants, including for Marvin Ramos Quintanilla, a former-gang-leader-turned-pastor. Prosecutors said Ramos led a double life, using a nonprofit network of Evangelical pastors to facilitate his role as MS-13’s CFO.

The network’s director, Pastor Nelson Valdez, told me that Ramos never used his chaplain credential to conduct MS-13 business. Following Ramos’s arrest, Valdez’s wife suggested he stop working with former gang members, but he hasn’t. “We have to make gangs and police better understand each other,” he said.

The police, and even Ramos’s fellow pastors, sometimes see it differently. Toby Jr. pointed to Ramos’s case as evidence that the gangs have corrupted the Evangelical community. Despite his pride in Taber’s gang converts, he estimates only a fifth of them overall are genuine.

The Salvadoran police seem to share the view. Cops still harass Charlie, now working at his Taber janitorial job, telling him, “You’re a murderer.”

“They see my tattoos and they see me as who I was, not who I am,” he said. “The civil war ended, but blood is still being shed in the streets.”

The next day, outside the thick haze of central San Salvador, Taber’s truck lurched to a stop, and a troupe of preachers clambered out, leaving gleaming Bibles and plastic bags of powdered milk in the flatbed. The steep street was hot and empty, and Brother Borja turned his sunglasses toward an alley that disappeared into colorful homes with corrugated-metal roofs.

“They will come,” he told me.

They did. Older women, young mothers, kids on their own. The crowd wordlessly formed an arc in front of Borja and the preachers. After prayers, the preachers distributed the milk and Bibles, and Borja offered to show us a view of the neighborhood. At the top of the hill, he extended a hand in greeting to two young guys who’d been standing watch—the exchange a tacit permission from the gang lookouts for the preacher to enter.

From the overlook, cinder-block houses built on an old municipal dump disappeared into the capital’s smog. Every narrow street was controlled by gangs, and below, people scattered at the sight of strangers where simply wandering onto the wrong block could be deadly.

Borja called down to a young man who looked up, holding one of the shiny Bibles just given out. Borja gestured for him to display the book, apparently for a photo op. Obliging the pastor, he raised the Bible up, but used it to cover his face.

Reporting for this article was funded by the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Chief Justice John Roberts made a bold declaration on the state of American race relations in 2013. “Our country has changed,” he concluded in his majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, “and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.” With those words, he and the court’s conservative majority gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Brian Kemp, Georgia’s secretary of state, seems to be on a one-man mission to prove Roberts wrong. The state purged more than 500,000 voters from the rolls under his watch in 2017, raising the likelihood that thousands of voters may be unable to cast a ballot when they show up to the polls next week. The Associated Press reported earlier this month that his office also froze 53,000 voter applications under its “exact match” policy, which allows officials to reject voter registration forms if the applicants’ information doesn’t precisely correspond with state and federal records—even if it’s only off by a comma or a hyphen. Seventy percent of those forms were filled out by African Americans. Kemp is in a tight race for governor against Stacey Abrams, who would be the first black woman ever to hold that position in the country.

Though Kemp is receiving the most attention during this election cycle, his actions are far from unusual. Officials in Republican-led states have enacted a variety of restrictive voting measures over the past decade similar to the ones he’s pursued. They defend these measures as a prophylactic against voter fraud, which is virtually nonexistent. But in practical terms, the greatest effect is to make it harder for thousands of Americans, particularly from disadvantaged communities, to vote. No small share of credit goes to the Roberts Court.

The Voting Rights Act is no ordinary piece of legislation. People died for it. Civil rights activists in the 1950s and 1960s were beaten, bloodied, and even murdered in the campaign to guarantee black Americans ballot access. Once enacted, it proved to be a powerful tool at sweeping away the last vestiges of Jim Crow and ensuring that states where it once thrived would not relapse into past deprivations. Measured by its impact, it ranks among the most effective pieces of human rights legislation passed in the twentieth century.

The law featured two key provisions. Section 2 established a permanent and nationwide ban on racial discrimination in election laws. The VRA’s most powerful weapon, however, was Section 5. That provision established a process known as “preclearance,” whereby certain states and counties with a history of racially discriminatory voting practices had to seek approval from the Justice Department or a federal court in D.C. before making any changes to their election laws. The bulk of the covered jurisdictions were initially in the Deep South. Over time, it expanded to cover Alaska and Arizona to protect Native American voting rights, as well as a smattering of counties throughout the Northeast and the West.

Preclearance amounted to an extraordinary federal intervention in state and local election laws, but the VRA’s drafters argued it was necessary to reverse almost a century of racist voter suppression in the South and elsewhere. “I think it is time that strong medicine be taken for this malady that has come upon us,” Kentucky Representative Frank Chelf remarked during a congressional hearing on the law. “Maybe we need some 110-proof Kentucky bourbon instead of the mild, gentle, soft, mellow, whispering, 86-proof, discriminating whiskey, if you know what I mean. Maybe we even need some block and tackle whiskey. That’s the kind, you know, you take a drink, you walk a block, and you tackle anybody.” The Supreme Court agreed and upheld the procedure’s constitutionality in 1966.

For decades, the law seemed legally and politically secure. Congress reauthorized the VRA with overwhelming bipartisan support in 2006, extending preclearance over certain jurisdictions for another 25 years. But a legal challenge to the extension by a utility board in Texas opened the first crack in the law’s foundation. In 2009, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder that the board could apply through the VRA to opt out of preclearance. Roberts, writing for the court, also raised questions about the constitutionality of preclearance itself.

“More than 40 years ago, this court concluded that ‘exceptional conditions’ prevailing in certain parts of the country justified extraordinary legislation otherwise unfamiliar to our federal system,” he wrote. “In part due to the success of that legislation, we are now a very different nation. Whether conditions continue to justify such legislation is a difficult constitutional question we do not answer today.”

Meanwhile, in Georgia, which had been subject to preclearance from the beginning, the VRA was proving as valuable as ever. Before Kemp became secretary of state in 2010, Georgia was twice blocked by the Justice Department from implementing a version of the exact-match policy. But the Obama administration may have seen the warning signs in the Roberts Court’s ruling in Northwest Austin: The Justice Department abandoned its legal fight against the exact-match policy, approving a modified version of the program shortly after Kemp entered office.

At the time, civil rights lawyers suspected that the Obama administration settled the state’s lawsuit to avoid giving the Supreme Court a chance to strike down part of the Voting Rights Act. Those fears were well-founded. When the court took up the issue again in Shelby County in 2013, the conservative justices’ skepticism was apparent.

“Is it the government’s submission that the citizens in the South are more racist than citizens in the North?” Roberts asked during oral arguments. Justice Antonin Scalia made the bewildering suggestion that Congress only reauthorized the VRA in 2006 because lawmakers would not be re-elected if they voted against it, as if that were not how representative democracy should work. “Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get out of them through the normal political processes,” he added.

Civil rights groups warned the Roberts Court that its ruling could have dire implications. “This Court’s decisions in the 1870s to invalidate federal voting rights legislation paved the way for Southern states to enact laws that effectively barred African Americans from exercising their right to vote for many generations,” the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights told the justices in a friend-of-the-court brief. “If this Court were to invalidate Section 5, there is a very real and substantial risk that this history would repeat itself. The Court should not allow this to happen.”

Georgia Representative John Lewis, a civil rights hero, told the court that Barack Obama’s election showed how far the nation had come since Alabama state troopers fractured his skull during the Selma-to-Montgomery marches for voting rights in 1963. At the same time, he warned that the Obama era had also reinvigorated a darker part of the American soul. “In response to more minority voters participating in the political process, six of the nine states fully covered under Section 5 have passed legislation in the last two years designed to restrict voting rights and access to the polls,” he wrote. “These laws hearken back to the days of Jim Crow, and remind us all that we have not left the past behind.”

In the end, Roberts and the other four conservative justices left Section 5 intact, and instead struck down Section 4(b) as unconstitutional. That provision listed which jurisdictions would fall under Section 5. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted in her dissent, the House and Senate held 21 hearings on the matter during the 2006 reauthorization and had amassed a 15,000-page record as part of its deliberations. But Roberts and his colleagues swapped out the legislative fact-finding process with their own policy assessment and found the law wanting.

“Congress did not use the record it compiled to shape a coverage formula grounded in current conditions,” Roberts wrote. “It instead reenacted a formula based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relation to the present day.” The judicial sleight of hand meant that the court could avoid striking down preclearance itself. Roberts noted that Congress was free to pass a new coverage formula, but he must have known that the Republican Party had no interest in doing so. Preclearance is now a sword that can’t be unsheathed.

Ginsburg compared the majority’s ruling to throwing away an umbrella because it wasn’t raining outside. But Kemp downplayed the implications of the court’s ruling. “It doesn’t mean that we don’t still have to follow the law or that we won’t get sued if we don’t follow the law,” he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “It just shifts the burden from us having to prove to other groups having to prove [discrimination], and that’s huge for the taxpayers of Georgia.”

While it’s impossible to know how the Justice Department would handle individual preclearance cases today if the provision were still in force, the trajectory in Georgia is clearer, according to Danielle Lang, a staff attorney at the Campaign Legal Center, which has challenged multiple iterations of the exact-match policy in court. “I think it’s a very fair statement overall to say,” she told me, “that we would not see the level of disenfranchisement that we see today if preclearance were still in effect.”

When I asked Moosa Elayah to describe where he was born—a province in Yemen called Ibb—the first thing he said was “green,” which makes sense. Ibb, in the southwestern corner of the country, is the wettest place in the entire Arabian Peninsula. It’s also a rare source of viable land for growing food and storing water in an otherwise dry, dusty country—one now facing a catastrophic, war-fueled famine.

But Ibb isn’t the same place it used to be, said Elayah, now a senior scientist at the Netherlands-based Centre for International Development Issues. “It was very green. Now it’s almost all stone,” he told me on Friday. Farmland has been replaced by buildings—many of which now hold starving Yemenis who have fled the civil war in the north. More than a quarter of Yemen’s two million internally displaced persons, or IDPs, have found refuge in Ibb, according to the World Health Organization.

Ibb may be Yemen’s most fertile ground, but its IDPs are still starving, WHO reports. This probably would have been the case even without a civil war. Yemen has never had enough arable land (less than 3 percent) to support its population (28 million people). Its population is starving today not because food can’t grow there, but because of a long-standing economic crisis exacerbated by the three-year war.

“Both sides are using food as a weapon of war, but the crisis is caused primarily by a brutal air, land and sea blockade imposed by a Saudi Arabia-led coalition,” according to CNN, which added that the blockade “has cut the amount of desperately needed food, medicine and fuel getting into the country by more than half, according to aid groups.”

But Yemen’s ability to grow its own food and access its own clean water is also decreasing as the number of starving people grows. This is due to a number of factors, including climate change. “It is not that climate change itself is causing the [hunger] crises,” said Elayah, who wrote a paper on the subject last year. “It is that climate change is increasing the suffering of the people.”

As The Guardian explained last year, “Although remote rural areas are able to grow corn and other basic crops during the rainy season, climate change has had an impact on their ability to survive during conflict. In the past, villages would store enough food to last for three or four months in times of emergency. In recent years less rainfall, resulting in reduced harvests, means little if any food is stored for periods of crisis.”

Drought has also contributed to water scarcity, which, Elayah argues, is driving conflict. “The civil war in Yemen seems to be a politically-motivated competition for power among many actors with varying motives,” he wrote in his paper. “But underlying all other motives is the ongoing need by all parties to secure access to the diminishing water supply.”

The idea that climate change is an exacerbating factor of conflict—such as the war in Syria—isn’t new. “The countries suffering from wars and conflicts are the same countries who are also struggling from problems of climate change,” Elayah said. That the effects of climate change have partly caused these wars, however, is still a controversial theory within the scientific community.

But it’s more widely accepted that climate change compounds suffering during conflicts. In Yemen, people have been warning about its effects for almost a decade, well before the civil war began.

“Possible climate change impacts, such as more violent and less predictable rainfall and a hotter and possibly drier climate,” a 2010 World Bank report read, “would place Yemen’s people and economy under further stress.” Four years later, the organization warned again that the region would “get hotter and drier” if warming trends continued. This would cause shorter growing seasons, which “could threaten food security and competition for dwindling natural resources could fuel conflict.”

War and corruption and overuse of resources are the primary reasons for suffering in Yemen. But because climate change makes conditions worse, Elayah argues, the countries who primarily caused those changes have a duty to step in and help. “This problem will continue influencing the country in different ways,” he said. “The international community should have the responsibility to protect the civilians in Yemen from hunger.”

He specifically admonished the United States for pledging to abandon the Paris climate accord, and China, a major trading partner of Yemen, for offering help mostly in the form of loans to support economic development. “It should be their responsibility to protect the poorer nations, the people who are suffering from the problem they caused,” he said. “The people in Yemen don’t have any means. They are dying of hunger every day.”

No comments :

Post a Comment