Almost exactly a year ago, Democrats did the unthinkable: They won a U.S. Senate seat in Alabama. Doug Jones, a former prosecutor, knocked off Roy Moore, the Alabama Supreme Court chief justice whose Senate run was undone by accusations that he had preyed upon teenage girls. It was a narrow victory, to be sure—20,000 votes, roughly 1.5 percentage points—but still an extraordinary one. It pointed to a possible playbook for Democrats in the deep-red Deep South, albeit a playbook that required a supremely toxic figure like Moore.

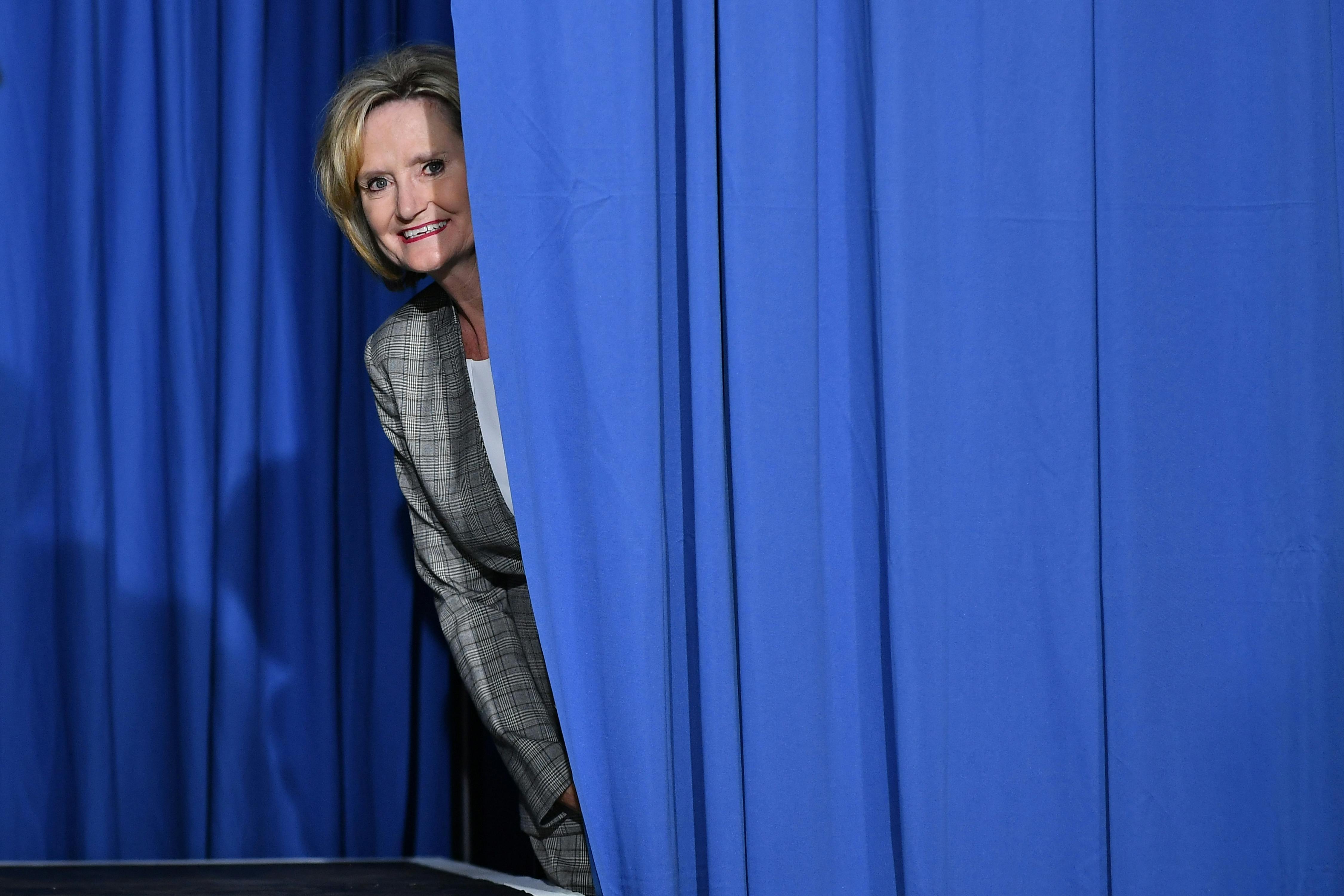

In Mississippi’s Senate race, Democrats may have found just such a figure. In a run-off on Tuesday, Mike Espy, a centrist Democrat best known for being the first African-American to serve as secretary of the Agriculture Department, will take on Cindy Hyde-Smith, who was appointed to replace the ailing Thad Cochran in the Senate earlier this year. An Espy win will not be easy. Donald Trump won Mississippi by nearly 20 points in 2016 (though, to be fair, Trump won Alabama by nearly 30). Mississippi has not elected a Democrat to the Senate since the Cold War, when it sent the ardent segregationist Dixiecrat John C. Stennis to Washington for the last of his eight terms. But while it is a long shot, a series of gaffes by Hyde-Smith have given Democrats hope that they can recreate the magic they found in Alabama a year earlier.

Hyde-Smith only narrowly beat Espy in the midterm elections, earning 42 percent of the vote to the Democrat’s 40 percent. (In Mississippi, a runoff is triggered when a candidate does not receive more than 50 percent of the vote.) But her totals were likely driven down by the presence of Trumpist and apparent white nationalist sympathizer Chris McDaniel, who garnered 17 percent of votes. With McDaniel out of the runoff, one can expect his voters to move to Hyde-Smith’s camp.

Hyde-Smith has certainly spent the last few weeks trying to attract them. Less than a week after the midterms, she made some apparently pro-lynching comments at a campaign event. (That’s right: pro-lynching.)

"If he invited me to a public hanging, I'd be on the front row"- Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith says in Tupelo, MS after Colin Hutchinson, cattle rancher, praises her.

Hyde-Smith is in a runoff on Nov 27th against Mike Espy. pic.twitter.com/0a9jOEjokr

Hyde-Smith’s comments unsurprisingly resulted in a huge wave of criticism. “Hyde-Smith’s decision to joke about ‘hanging,’ when the history of African-Americans is marred by countless incidents of this barbarous act, is sick,” wrote Derrick Johnson, the president of the NAACP. After Hyde-Smith refused to apologize, a number of corporate donors to her campaign, including Walmart and Union Pacific, demanded their money back.

Then, a few days after the lynching controversy, she told supporters that “maybe we want to make it just a little more difficult” for college students to vote, another comment with ugly resonance given Mississippi’s Jim Crow history. And almost two weeks later, she posed for photographs holding a rifle and wearing a Confederate cap.

Espy called Hyde-Smith’s comments “awful,” but stopped short of describing them as racist. Still, her remarks likely agitated the Democratic base, which could be bad news for Hyde-Smith: In Alabama’s 2017 special election, black voters turned out in droves to defeat Moore, who had fought to keep segregation in Alabama’s constitution. An internal Republican poll found that Hyde-Smith’s lead over Espy “had narrowed to just five percentage points,” according to The New York Times.

That may explain why Hyde-Smith finally decided to apologize for her comments in a debate against Espy on Tuesday night—sort of. “For anyone who was offended by my comment I certainly apologize,” she said. But she then attempted to turn the controversy on its head and blame Espy, saying her words were “twisted” and “used for nothing but political gain.” Espy hit back: “Nobody twisted your comments because they came out from your mouth.” Hyde-Smith’s comments, he continued, have “given our state another black eye,” by bolstering “stereotypes we don’t need anymore.”

Espy has an uphill climb. According to Vox, Democratic strategists have a clear goal for turnout: “Thirty-five percent of Mississippi’s population is black, and Democrats need them to make up at least that much of the electorate—preferably more, of course—to have a chance.” The centrist Espy is also hoping to pick off moderate Republicans. In Tuesday’s debate, he distanced himself from his party and made the case that he would be a forceful advocate for his state’s interests, touting a “Mississippi First” approach. “That means Mississippi over party. Mississippi over person,” he said. “I don’t care how powerful that person might be. It means Mississippi each and every time.”

During the debate, he also underscored his strong positions on gun rights and promised to push for a “strong immigration policy.” Meanwhile, concerns about health care, one of the defining issues in the midterms, may help Espy, who has returned to the subject again and again on the campaign trail. Hyde-Smith claims that she supports coverage of pre-existing conditions while also demanding that the Affordable Care Act be repealed. (This common Republican position is, of course, nonsensical, and voters punished the GOP for it in other states.)

Hyde-Smith’s strategy is built entirely on base turnout. She has campaigned as a mini-Trump, and the real thing will be appearing at a rally with Hyde-Smith on Monday, the day before the election. “I think we should definitely build that wall,” she said in the debate. “We can’t have people storming our borders.” Her gaffes may have hurt her campaign, and she may have used racist dog whistles against her black opponent, but she is not quite Roy Moore, a racist, a homophobe, and an accused pedophile.

Still, if Mississippi is going to turn blue—if only for a moment—the time is now.

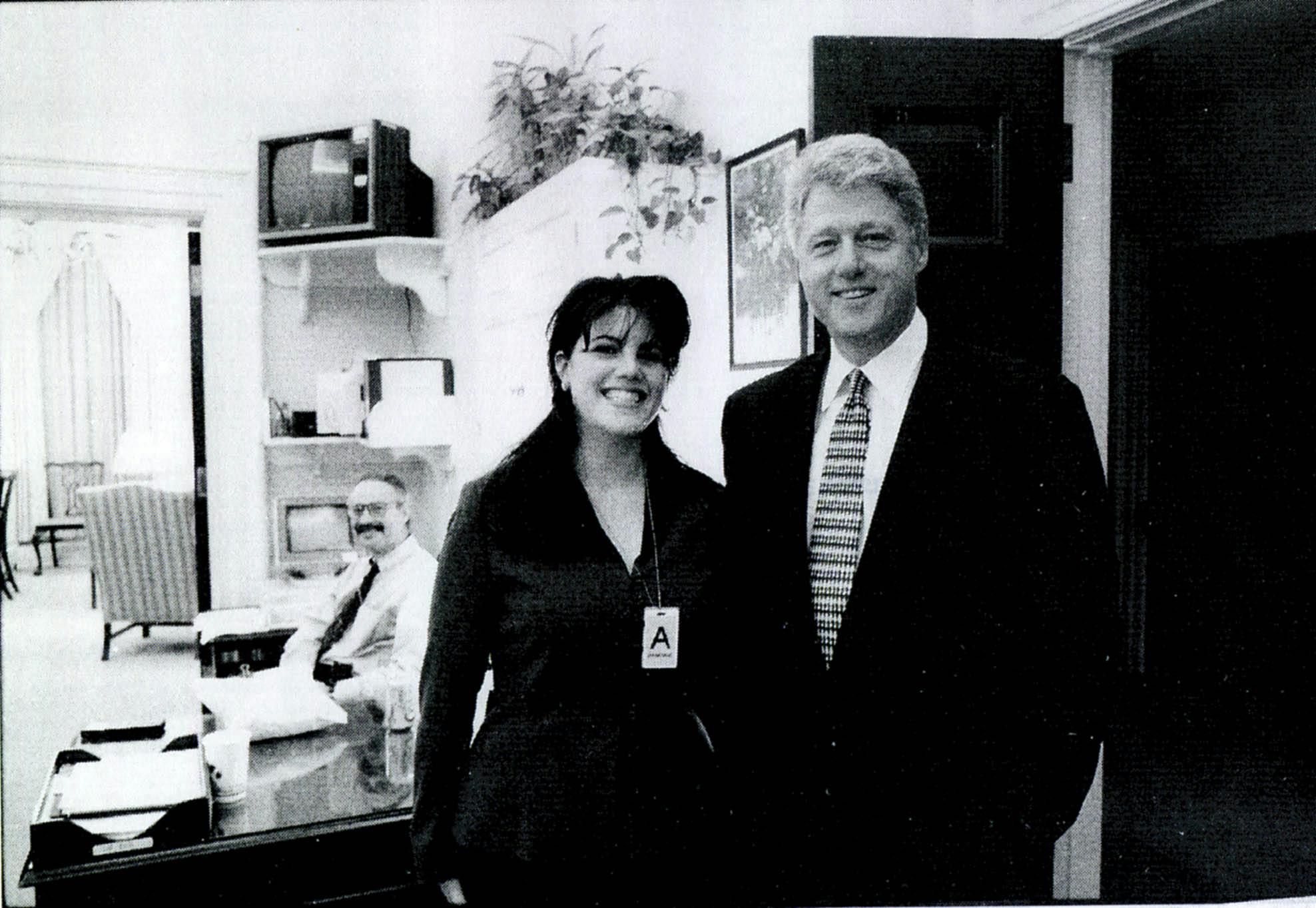

For three consecutive days in April of 2001, a then 27-year-old Monica Lewinsky sat on the stage of New York’s Cooper Union auditorium, answering questions from a packed audience composed of law students and graduate students in women’s studies and American history. Lewinsky and a team of two documentarians—Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, the founders of World of Wonder Productions, the company behind Party Monster, Inside Deep Throat, The Eyes of Tammy Faye Baker, and more recently RuPaul’s Drag Race—stocked the public Q&A with a thoughtful crowd and then informed them that they had permission to ask her anything. For the first time, she was legally allowed to speak publicly not only about the Clinton affair, but also about Linda Tripp, who secretly recorded Lewinsky talking about her interactions with the President and then slipped those tapes to Kenneth Starr’s team.

Lewinsky fielded questions for over ten hours during three filmed sessions, which Bailey and Barbato then cut into the 95-minute HBO special Monica in Black and White, which aired on the cable network in early 2002. The title of the documentary (which you can now find on YouTube) refers to both Lewinsky’s outfit—she wore a black pantsuit and white button down shirt—and the fact that the film is not in color (lending a patina of gravitas to the whole undertaking). But it is also a knowing wink: Lewinsky’s story is and has always been a cultural gray area, and a moving target. Since the news broke of Bill Clinton’s affair with a 22-year-old White House intern in January 1998, Lewinsky has been called many things in the media: a victim, a seductress, a punchline, a heroine, an innocent, a vamp, a feminist icon, a camp icon, a cautionary tale, an inspiration.

The “real” Lewinsky was, of course, lost in all of this, even as projects like the HBO documentary attempted to show her unfiltered truth. When Monica in Black and White first aired, a New York Times reviewer (a woman, I might add) called it “Monica The Infomercial,” and argued that it “panders to Ms. Lewinsky’s image-reconstruction project…. She comes across as someone who is trying hard to invent a new image but isn’t very good at it.” The reviewer runs through a laundry list of Lewinsky’s public appearances (the Herb Ritts shoot for Vanity Fair, the Jenny Craig ads, the big Barbara Walters interview) and sneers that “with every public relations gambit she becomes less sympathetic.” This lingering disdain prompts a lingering question: What was Lewinsky supposed to be doing instead? She stated several times that she never wanted to become a public figure, that she never wanted her name splashed across 60 Minutes or turned into a parodic jingle on the Howard Stern Show. But once the Tripp tapes aired on C-Span and Congress voted to release the Starr Report online in its entirety, Lewinsky didn’t have a choice. She could try to disappear (which she did, for several years following the HBO special) or she could try to show her side of the story.

When Lewinsky made the television special in 2002, her story still felt very raw, and she—understandably—didn’t seem to have much distance from it yet. When she first sat on stage, she told the audience that she was “very nervous” and she rocked back and forth in her seat. At one point, she sits directly on the stage floor, with her legs crossed into a pretzel front of her, curling herself up into as small a shape as possible in the face of the verbal barrage. She is able to defend herself (one man stood up to say he found the entire evening distasteful, and she cooly shot back, “Why did you come here tonight, sir?”), but she also pauses often to hang her head in her hands, overwhelmed by the requests to recount her humiliation over and over. At one point, someone in the back of the crowd shouts “We’re on your side, Monica!” and her sigh of relief is palpable. For Lewinsky, nothing at the time was black and white; it is clear she was wandering around in a haze, trying to make sense of what had happened to her and how her public and private selves had become so bifurcated.

Sixteen years later, Monica Lewinsky, now 46, is again telling her story on television, this time as one of several interviewees who sat for a new six-part documentary from director Blair Foster, called The Clinton Affair, which airs over three nights this week on A&E. This time, her interviews are in full color. She wears a pink blouse, the color of California bougainvilleas, and speaks with a composed confidence; she seems to know that she is releasing her story into a far different world this time around.

Since returning to the spotlight with a Vanity Fair essay about weathering public shame in 2014 and a viral TED Talk in 2015, Lewinsky has managed to wrestle back some measure of control over her side of the narrative. She now regularly contributes to Vanity Fair, placing her experience in the context of the #Metoo movement, and this year, she promoted an anti-bullying campaign that involved celebrities briefly changing their Twitter display names to the public slander that had hurt them the most (Monica changed hers to “Monica Chunky Slut Stalker That Woman Lewinsky”). She has begun to align herself with historical feminist agitators, such as the activist and poet Muriel Rukeyser—in an essay about why she chose to participate in the A&E documentary, Lewinsky wrote,

Rukeyser famously wrote: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.” Blair Foster, the Emmy-winning director of the series, is testing that idea in myriad ways. She pointed out to me during one of the tapings that almost all the books written about the Clinton impeachment were written by men. History literally being written by men. In contrast, the docuseries not only includes more women’s voices, but embodies a woman’s gaze.

Lewinsky seems to not only have found her voice, but also her people: She doesn’t have to carefully select rooms full of Women’s Studies majors to find a sympathetic audience. Though the director of The Clinton Affair interviewed dozens of talking heads from all sides of the scandal (Kenneth Starr, James Carville, Bob Bennett, David Kendall, Lucianne Goldberg, Lewinsky’s parents and close friends—the only notable absences are Tripp and the Clintons themselves), the show’s sympathies lie with Lewinsky as it highlights the hideous ways that the media raked her over the hot coals of judgment. One particularly effective segment comes in episode 5, as Foster puts together a maddening montage of various late night television hosts making misogynist jokes or slut-shaming commentary about Lewinsky, one CNN commentator going so far as to call her a “young tramp” with no sense of irony.

You will find a similar montage in the seventh episode of Slow Burn, a new podcast from Slate’s Leon Neyfakh that also aims to deconstruct the Clinton affair, breaking down the complicated tabloid fervor of the late 1990s for contemporary listeners. While Lewinsky did not speak to Neyfakh for the show, the episode, “Bedfellows,” does much of the same work as The Clinton Affair. As it dissects the feminist response to the scandal and picks apart a particularly damning New York Observer roundtable in which several women writers defended the President, it notes just how poorly so many people, women included, treated the young Lewinsky at the height of her notoriety.

Between The Clinton Affair and Slow Burn, we are at a time of re-evaluating the culture wars of the 90s. By placing them in a historical context, we both examine and distance ourselves from events that are more recent than we’d like to think. This is an ongoing trend; in the last few years, popular entertainment has re-imagined and re-considered 90s headlines, from the OJ Simpson trial to the Tonya Harding incident to the Versace homicide to Princess Diana’s death. In each of these, it isn’t only figures like Monica Lewinsky who want to reshape and reclaim the narrative. These shows also give the audience a chance to do the same—to relive events and experience a more enlightened set of sympathies. New biopics and documentaries about this period are rarely surfacing new facts; they are presenting a way of feeling about the events and the lives caught up in them.

The Clinton Affair itself is not a perfect film. It drags at times, and at others feels too quickly paced. (Foster interviews Juanita Broaddrick at the end of the documentary, with only a few minutes to spare). But it finally presents Lewinsky in color. And perhaps, most importantly, it brings other women into frame. Foster gives nearly equal screen time to Lewinsky and to Paula Jones, the woman whose sexual harassment case against Clinton sparked the broader investigation into Clinton’s affairs (Clinton continues to deny her allegations). Lewinsky has endured impossible humiliations over the past twenty years, and it is moving to see her speaking up for herself with such eloquence and wisdom. But Jones, whose story also became a political cudgel (as recently as Trump’s campaign, when she sat in a press conference with him), has not had as many opportunities to reengage with the public. Jones’s tears throughout her interviews feel almost as searing and bruised as Lewinsky’s did sixteen years ago, when she was stumbling through the fog of fresh pain. While their stories are now landing on increasingly sensitive and engaged ears and achieving something close to televised vindication, it is clear, watching the two of these women relive the events that defined and eclipsed half their lives, that the hurt they endured cannot be undone.

Gary Hart, the Democratic presidential candidate I worked for in 1984 and would have supported again in 1988, has been back in the news. The Front Runner, a film that presumes to explain the murky sex scandal that forced him from his presidential run in 1987, came out in late November. Prior to that, James Fallows, like me a longtime admirer of Gary, wrote a piece in The Atlantic speculating—on the basis of a supposed deathbed confession by the unscrupulous Republican operative Lee Atwater—that the initial stage of the imbroglio may have been a setup that Atwater himself engineered.

The renewed attention to these unhappy events should not obscure the important contributions Hart has made over the past 30 years to American government and—even more significant—to American political discourse. He has participated in a panoply of councils and commissions. Most notably, he was co-chair, along with former New Hampshire Senator Warren Rudman, of the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, which predicted massive terrorist attacks on American soil, possibly involving airplanes, shortly before 9/11. Such activities—in which he has served the government in his capacity as a private citizen—are very much in keeping with the ethos of civic republicanism, the political-philosophical tradition that, after shuttering his campaign, Hart came to embrace as his own.

The overarching goal of his intellectual journey, he told me recently, was to establish a connection between democracy and citizen participation. His quest led him early on to the work of American historian Gordon S. Wood, who in his writings elaborated on the decisive influence that the republican tradition had on America’s founders. (A review by Wood appears on page 46 of this issue.) Reading the historian, Hart said, “A light went off in my head: Democracy is about rights, republicanism is about duties.” The realization transformed his thinking. “My mantra became, we must protect and secure our rights by the performance of our duties—meaning participation in self-government.” Hart also discovered Jefferson’s concept of the “ward,” or “elementary republic,” as the forum for citizen participation, a unit small enough to mimic the Greek assemblies that governed ancient Athens, where both democracy and the republican tradition were born.

In the early 2000s, Hart repaired to Oxford University, where he earned a D.Phil. in Politics, at the age of 64, with a thesis entitled “Restoration of the Republic: The Jeffersonian Ideal in 21st Century America.” In calm, measured tones befitting a doctoral dissertation, the work queried whether the United States could still be legitimately classified as a republic. Fourteen years later, Hart presented a more acerbic version of his views on the subject with the 2015 book The Republic of Conscience. Explaining the definition, according to classical republicanism, of “corruption”—government officials putting their own personal interests ahead of those of the general public and the common good—Hart describes the American government as “massively corrupt,” detailing a “permanent political class” consisting of “a network of lobbying, campaign fund-raising, and access to policy makers in administrations and lawmakers in Congress ... based purely and simply on special and narrow interests.”

The examiners of Hart’s Oxford thesis had written, “Hart clearly believes that the Jeffersonian picture is one of increasing relevance to the United States, and the thesis is at times a powerful piece of advocacy for that picture.” What, exactly, is the “Jeffersonian picture”? Historically, successful republics had always been small in size, but the Founding Fathers were establishing a republic they hoped would eventually stretch sea to sea. To address the problem of size, they borrowed Montesquieu’s concept of a federated republic, which they combined with a system of electoral representation, a relatively new political concept at the time. Jefferson, however, criticized this plan for not creating any public space for direct citizen participation in government, and later he advocated for very small townships— his “ward” republics—in which citizens could debate and settle issues specific to their area alone, such as those involving local public schools.

Enter, again, James Fallows. He and his wife, Deborah, published an important book this year, Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey Into the Heart of America. The Fallows sought out, in towns and smaller cities across the country, examples of people working across ideological lines to accomplish projects of benefit to the whole community. “Overwhelmingly,” the couple observe, “the focus in successful towns was ... on practical problems a community could address. The more often national politics came into local discussions, the worse shape the town was likely to be in.” And the most successful towns, they concluded, were those with the most distinctive, innovative schools—the kind, one may hazard to guess, a ward republic might be wont to create.

Every day, rescuers at the ongoing Camp Fire in Northern California are discovering a new body of somebody’s loved one, burned or suffocated to death. They’re often pulling these people from the ashy rubble of their former communities. This daily activity has no known end date; it must continue until all 870 missing people are found. And even then, the ultimate toll of what has become the deadliest wildfire in U.S. history will be unknown. For some, the long-term affects of breathing in smoke could bring about an earlier end to their lives.

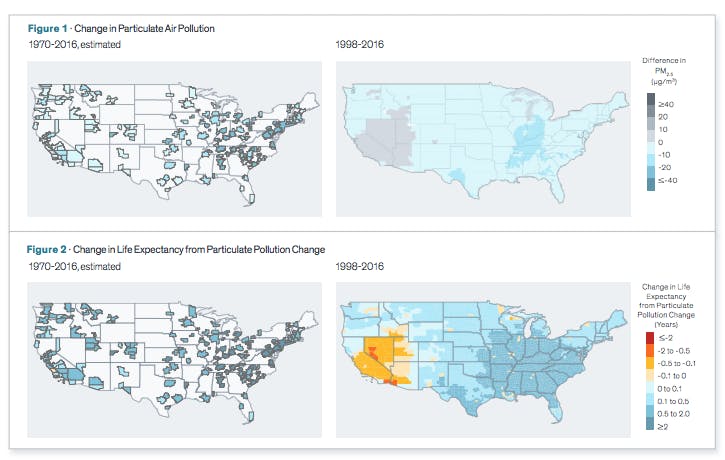

In the middle of a wildfire, exceedingly thick smoke can cause people to immediately asphyxiate. But more limited smoke exposure—the kind millions in the Bay Area are suffering from as a result of the faraway Camp Fire—can also have a long-term effect. California as a whole already has the highest levels of particulate air pollution—otherwise known as smog—in the United States. And as a new index released Monday by the University of Chicago shows, long-term exposure to high-level smog pollution takes a meaningful toll on human life.

The new metric, known as the Air Quality Life Index or AQLI, is an attempt to quantify the long-term health impacts of inhaling particulate matter, which refers to tiny particles of material that can penetrate deep into the circulatory system and potentially infiltrate the central nervous system. Overall, the AQLI asserts that long-term exposure is reducing the average life expectancy by 1.8 years—making it “the greatest current threat to human health globally.”

Americans, for the most part, aren’t affected by this threat. The majority of smog’s affect on human life expectancy comes from smog generated from fossil fuel plants in China and India. But Californians are certainly affected, as their state has the worst long-term air quality in the country. In many areas, the researchers behind the AQLI have predicted, particulate matter pollution has shaved one year off residents’ average life expectancy.

California’s air pollution has worsened since 1998, causing a decline in overall life expectancy for many state residents. Air Quality Life Index

California’s air pollution has worsened since 1998, causing a decline in overall life expectancy for many state residents. Air Quality Life IndexWildfire smoke is not helping this situation. In fact, some areas of the state now have more smog than the smoggiest cities in the world because of smoke drifts from the Camp Fire and other wildfires. This is producing short-term physical affects in some residents. “I had a bloody throat, bloody nose, a cough, dry and watering eyes, and my throat is still very sore and dry,” a UC Berkeley student told CNN. “I almost passed out trying to go to class yesterday. My professor told me to go home.”

Long-term affects to wildfire smoke are still mostly unknown; most studies on the health impacts of particulate matter come from fossil fuel sources, not wildfires. As the San Francisco Chronicle notes, there are some differences between the two types of smog “that scientists don’t fully understand.” Researchers do guess, however, that smoke from burned residential areas might be more toxic than a pure forest fire, because of the various chemicals contained within man-made materials.

To look for clues on how long-term exposure might affect human health specifically, researchers are looking to fossil fuel pollution studies. Asthma and pregnancy issues thus top the list of potential risks, along with heart problems. “When we talk about particulate matter, we always think, ‘Oh, well, the target organ is the respiratory tract, the lungs,” wildfire smoke researcher Kent Pinkerton told the Sacramento Bee, “but far more people have problems with cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality due to PM exposure than respiratory conditions.”

But the AQLI has made one impact clear: The more humans are exposed to particulate matter, the shorter their average life expectancy becomes. And humans in California risk getting exposed to a lot more particulate matter as climate change worsens and exacerbates wildfires.

Does that mean Californians are doomed to die earlier than the rest of Americans because of climate change? Not at all; in fact, Californians have the fifth-longest life expectancy of all state residents across the country. But it does mean tackling carbon emissions will be required for them to keep it that way.

As German chancellor Angela Merkel arrived in the eastern Saxon city of Chemnitz on Sunday, Mustafa B., a Turkish medical student who had moved to the city two months ago, was trying to figure out if it was safe to cross the road. The reason for his apprehension lay across the street: A group of men dressed in all black had begun to march up and down the sidewalk. “Thanks Merkel!” they screamed as their leader, a former member of the neo-Nazi Blood and Honor movement, shouted further slogans into his microphone.

Mustafa B. turned to a nearby policemen to ask about the purpose of the protest. The officer snorted: “Do you understand sarcasm?”

Since the far-right riots in late August and September this year triggered after a German man was allegedly murdered by two asylum seekers, downtown Chemnitz has played host to weekly demonstrations against immigrants and the government seen as letting them in. The group that gathers features individuals seemingly further right than the strongly anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland party (AfD). The AfD politicians who joined the protests in early September “just got into their expensive cars and disappeared” afterwards, said Benjamin Jahn Zschocke, the spokesperson for local lawyer Martin Kohlmann, who speaks weekly at these Friday night gatherings. Kohlmann attends summits where former SS members and Holocaust deniers give speeches about life in Nazi Germany. At his Friday night addresses, he calls for armed “resistance” against the German government over its pro-immigration policy.

To some locals, all these events are being blown out of proportion by German and international media. Yet NGOs have recorded a significant increase in hate crimes in Chemnitz, the state of Saxony and elsewhere in Germany in the past two months coinciding with the uptick in far-right activity. And it’s enough to make those who stand out—whether with an anti-fascist sticker on their backpacks or external appearances that don’t immediately code as “German”—start worrying about their safety.

“They think: well if he’s a Nazi for not wanting immigrants here, then I guess I am too.”Standing in the crowd outside the auditorium in which Merkel was speaking on Sunday, a 50-year-old nurse with blonde bangs named Marlene told me she’d been marching with the far-right Pro Chemnitz demonstrators every week since the summer. On the night after Daniel Hinnig, the man whose death triggered the riots, was stabbed, she was on the streets with the other far right protesters. She didn’t see neo-Nazis chasing migrants or performing illegal Hitler salutes, she told me—video footage and eyewitness accounts of the banned salutes eventually led to prosecutions—and is convinced the government lied about them. Since then, however, the core group of hooligans and skinheads at the Pro Chemnitz rallies has been impossible to overlook.

In 2016, the recorded number of racist and xenophobic attacks in Germany spiked dramatically. But last year, despite the xenophobic Alternative for Germany being elected into parliament for the first time as the leading opposition party, that number decreased. So for Andre Löscher, who is a counsellor for victims of far-right violence in Chemnitz, it was scary to note that since the riots in August, forty-seven racist hate crimes have been reported, which is already twice the total number of hate crimes recorded for the small city last year. Four restaurants have been attacked. On September 14, a group of men walked into a park and threw a glass bottle at a 26-year-old Iranian’s head after demanding to see his and his friends’ identification; it later turned out that some of the men in the group of attackers were making a plan via Whatsapp to buy guns and “overthrow the media dictatorship and its slaves” on the anniversary day of German reunification, on October 3. On the 80-year anniversary of Kristallnacht, the 1938 pogrom against Germany’s Jews, a dozen “stumbling stones”—bronze plaques that commemorate residents who died in the Holocaust—were smeared with oily tar, while the Pro Chemnitz lawyer made a call to arms against “the Merkel regime.”

A similar pattern of violence has played out in Wurzen, another Saxon city that was previously terrorized by neo-Nazis in the post-reunification chaos of the 90s. Recently, there have been a series of arson attacks and physical assaults on the street. In the evenings, youths who call themselves “the people’s militia” get drunk and march through the city chanting “Out, foreigners!” They’re the sorts of street protest associated with the groups like PEGIDA (an acronym that stands for Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West). In Saxony, Löscher has observed that when Pegida and other far right demonstrations started to wane a few years ago, hate crimes decreased in the areas where protests stopped. Now, both the demonstrations and the hate crimes seem to be back. “When so many people are moving around in the streets and notice that they are many,” he says, “It really motivates them.”

Yet there are signs of pushback. A few weeks ago, the Chemnitz city council installed shiny new cameras in the city center to restore a sense of security. In Berlin, 242,000 people took to the streets last month to protest against the far right. 75,000 people showed up in September to an anti-racism rock concert in Chemnitz. Next week will be the first time since August that Pro Chemnitz will not hold their Friday night rally. And barely two weeks after the far-right’s nemesis, Angela Merkel, announced that she would not seek re-election as German chancellor—cause for celebration among the anti-immigrant crowd—demonstrations during her Sunday visit were relatively restrained.

Like the far-right street movements before them, and also somewhat like President Donald Trump in the United States, speakers at the Pro Chemnitz rallies do their best to assure people that the media lies about their crowd size. (“I see at least 5000 people!”, one guy blustered at Friday night’s rally. The police estimated 2,500.) But however intimidating they may understandably be to their targets, it’s also clear the groups lack real momentum. “We are too few,” one man says. He has been active in far-right politics since he broke up with his long-term girlfriend one year ago. But now that daylight is limited and winter is coming, “I can also think of other things to do on a Friday night instead of freezing my ass off here.” Even Marlene, who spent most of the evening reciting the latest conspiracy theories the far-right has concocted based on the UN migration pact, and who is convinced that “doom is coming,” agrees.

But whether the demonstrators begin to dwindle or not, something has shifted in Chemnitz, and in a way earlier generations might find disturbing: Increasingly, a past once seen as unforgivable is starting to be normalized. Some of the first-time demonstrators—people who don’t pledge allegiance to any right-wing extremist group, but who have in past weeks joined the crowd that chants “Out, foreigners!”—have begun to angrily describe themselves as “Nazis” on social media, in response to what they perceive to be the political and cultural establishment’s unfair stereotyping. “For some, these skinheads are their friends and neighbors,” Phillip T., a young Chemnitz photographer, said. “They think: well if he’s a Nazi for not wanting immigrants here, then I guess I am too.”

This suits the radical right just fine: A neo-Nazi label in Thuringia has already started printing T-shirts that read “N.A.Z.I: Nicht an Zuwanderung interessiert,” which translates to: “Not interested in immigration.” As 2018 draws to a close, some of Germany’s most painful history is getting rebranded.

Given the volatile situation in Chemnitz in recent months, we have identified several private individuals in this article by first name only.

No comments :

Post a Comment