In 2016, an international team of scientists set out to determine how much of the earth’s land is still wild. They were alarmed at what they found: Deserts, grasslands, tropical and boreal forests are all rapidly disappearing. In the last two decades, 10 percent of terrestrial wilderness has been replaced by buildings, farmland, and other development. Only 23 percent of all land on the planet remains relatively untouched.

The ocean is in an even more dire state. In a study published this summer, a research team made up of some of the same scientists found that only 13 percent of the ocean can be classified as marine wilderness. The rest has been altered by anthropogenic stressors, such as industrial fishing, pollution, and shipping.

The ocean research was limited by a lack of historical data, so it’s unknown how quickly marine wilderness has declined in the last 20 years. But the two papers make one thing clear: Humans are threatening a complete takeover of both the land and the sea. After climate change, it’s the most urgent environmental crisis of our time.

On Wednesday, the scientists led by Australia’s University of Queensland attempted to explain why the impending disappearance of wild places is so dire. “Numerous studies are starting to reveal that Earth’s most intact ecosystems have all sorts of functions that are becoming increasingly crucial,” they wrote in the prestigious journal Nature.

The general public may view wilderness areas like recreational facilities. But scientists see them more like libraries. They contain a wealth of information about the natural world—why it has thrived for so long, how it adapts and evolves under the pressure of evolution, and what truly makes it die. They are “important reservoirs of genetic information, and act as reference areas for efforts to re-wild degraded land and seascapes,” the scientists wrote. The information contained in wild places allows researchers to predict what will happen as climate change worsens.

Speaking of climate change, untouched places also happen to be humanity’s biggest shield against the phenomenon. Tropical and boreal forests are carbon sinks: They absorb up to 40 percent of the carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere, thereby preventing it from causing rapid warming of the planet. Human development within these forests not only limits their ability to provide this critical function; it creates more carbon emissions by replacing the trees with high-emitting farming and logging operations.

Wild seagrass meadows provide a similar carbon-absorbing function in the ocean—that is, until they’re affected by pollution. When that happens, they “switch from being carbon sinks to major carbon sources,” the scientists wrote. Wild places can protect communities from extreme weather, too. “Simulations of tsunamis, for instance, indicate that healthy coral reefs provide coastlines with at least twice as much protection as highly degraded ones.”

Wild places are also critical habitats for wildlife, which is declining at a stunning rate. A report released Monday by the advocacy group World Wildlife Fund found that mammal, bird, fish, reptile and amphibian populations have declined at a 60 percent rate on average since 1970, a phenomenon due in part to habitat loss. This isn’t just bad for the animals, either. “There is a connection between loss of the natural environment and human health,” WWF’s chief executive Carter Roberts told the Washington Post. “Where does our food come from? Where does our water come?”

The complete degradation and disappearance of wilderness on the planet is a real possibility, but not inevitable. Some of the world’s wealthiest citizens are stepping up to save what’s left. Yvon Chouinard, the billionaire founder of outdoor company Patagonia, has used his company to donate $89 million toward conservation efforts, as well as advocate against the Trump administration’s anti-wilderness efforts. He also founded 1% For the Planet, an effort to increase environmental philanthropy. And on Thursday, Swiss philanthropist Hansjörg Wyss, who lives in Wyoming, announced in a New York Times op-ed that he’s donating “$1 billion over the next decade to help accelerate land and ocean conservation efforts around the world, with the goal of protecting 30 percent of the planet’s surface by 2030.”

But we can’t, and shouldn’t, hope that the rich will save Earth. Only governments have that power. That’s why the scientists writing in Nature propose a Paris climate agreement for the wilderness. “What is needed is the establishment of global targets within existing international frameworks—specifically, those aimed at conserving biodiversity, avoiding dangerous climate change, and achieving sustainable development,” they wrote. “In our view, a bold yet achievable target is to define and conserve 100 percent of all remaining intact ecosystems.”

It just so happens that the annual United Nations meeting on implementing the Paris climate agreement is scheduled for December. They’d be wise to add wilderness preservation to the agenda.

In a bid to whip up his base in the closing days before the midterm elections, President Donald Trump announced his intention to end birthright citizenship. The move shifts focus from the thousands of desperate women, men, and children fleeing violence and unrest in Central America to an even more vulnerable target: the approximately 275,000 babies born annually in the United States to non-citizen parents. With a stroke of his pen, Trump is hoping to do away with a right that is spelled out in the Constitution and which represents America’s historical values of equality and openness.

A day earlier, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, a fierce defender of liberal democratic values, announced that she would not seek another term after a foreboding election in the state of Bavaria in which a third of voters cited migration and the integration of foreigners as the biggest problem facing the state. The populist onslaught has been egged on by the anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany (Afd), which gained seats in last month’s election despite the fact that the number of refugees and migrants in the country has dropped markedly from highs three years ago.

On both sides of the Atlantic, politicians are portraying immigrants and refugees as a plague on society: job-takers and criminals who make us less prosperous and less safe. It’s a familiar narrative, usually untethered from the facts, that has been used throughout history to stir up democratic society’s worst—and most self-defeating—political impulses. If we don’t change course, the consequences could be dire, and not just for thousands of desperate immigrants who deserve a chance for a new life. History has shown that when immigration policy is tightened, we all lose.

In the mid-1800s, America learned the hard way that policy driven by anti-immigrant rhetoric has consequences not just for our moral standing, but our economy and national security. Chinese laborers in California were manning the gold rush and building the first transcontinental railroad. In doing so, they provided cheap labor and tax revenue to fill California’s fiscal gap. Mainly young, healthy males, these immigrants made little use of social services and health systems.

Still, when the post–Civil War economy declined in the 1870s, political leaders embraced and spread anti-Chinese sentiment, blaming the “coolies” for depressed wage levels. In California and around the country, states passed long-lasting anti-Chinese laws. So did the federal government: Chinese Exclusion Act deprived Western states and Hawaii of needed labor, tax revenues, and citizens available to fight and work during wartime.

This kind of erratic, transactional approach to immigration policy has been a defining feature of our relationship with Mexican migrants, which has been marked by spasms of expulsion motivated by political or ethnic antipathy, followed by a re-embrace whenever it’s perceived as serving America’s economic interests.

During the Great Depression, the U.S. government moved to deport Mexican-born workers and American citizens of Mexican descent in order to exclude them from welfare programs under the New Deal. Over one million Mexican nationals were removed in the 1930s. By 1942, there was a shortage of agricultural labor serious enough that President Harry Truman introduced the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, which offered legal, temporary work to Mexican migrants in exchange for a guaranteed wage and humane treatment. The so-called Bracero Program was a flop, in part because poor enforcement led employers to seek lower cost undocumented labor elsewhere. But it’s another example of the correction and collective “whoops” that often follows immigration policy when it’s based on bigotry instead of facts, at great cost to the American taxpayer.

With the U.S. still mired in conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the demonization of Muslims and people of Middle Eastern descent is equally counterproductive, and potentially even dangerous. This year marked the first time in over a decade that the military has fallen short of its recruiting goals. For years, the military has actively sought talent from ethnic minorities with knowledge of the languages and customs of other nations, bringing immigrants and refugees into the defense community precisely for their burning desire to fight the tyranny and persecution they left behind. Programs like Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest, or MAVNI, welcomed such individuals into the military in exchange for a fast track to citizenship. More than 10,000 people joined the military, mostly the U.S. Army, this way. The program was suspended earlier this year as part of the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown.

Foreign student enrollment in U.S. universities is down after a decade of growth, sending some of the world’s smartest young minds to countries less hostile to immigrants. Scientists are leaving the U.S., taking up posts in Canada, China and elsewhere. Approvals for H1-B visas, frequently used by high-skilled workers in the tech industry, are down.

These policies are based on straw-man arguments that conflate terrorism with immigration. Of the nearly 800,000 refugees resettled in the United States since 9/11, just three have been arrested for planning terrorist activities. Between 2001 and 2015, more Americans were killed by homegrown right-wing extremists than by Islamist terrorists.

When it comes to the economy, a large body of research shows that immigration confers net benefits to society. Indeed, the president’s dehumanizing rhetoric toward immigrants comes at a time when he himself boasts of an economy that is “booming like never before.” That’s classic Trumpian embellishment, but it’s true that the economy is growing at a healthy clip, undermining Trump’s own assertions that immigrants are hurting the economy. A recent study by Citi Global Perspectives and Solutions concluded that migrants are directly responsible for two thirds of U.S. economic growth since 2011.

Delusions about immigrants are hardly limited to the far-right fringe. The same Citi Global study found that across countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, host citizens believed that human flows were far larger, jobs far fewer, and migrants less productive in the labor market than they actually were.

A study by Harvard economists uncovered similar misperceptions. In France, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and the U.S., the average native believed that there are between two and three times as many immigrants as there are in reality. In the U.S., legal immigrants are about 10 percent of the population, but U.S. respondents believed the figure was 30 percent. In all countries, immigrants were viewed as poorer, less educated, and more likely to be unemployed than they actually were, and this was believed to be mainly because of lack of effort rather than adverse circumstances. In all countries except France, respondents overestimated the share of Muslim immigrants by a wide margin.

In this age of obfuscation, we’ve become desensitized to political rhetoric that ignores the facts. One right-wing website, Gateway Pundit, described people in the migrant caravan as “invading migrants” who are “organized into groups and sub-groups like an army.” That’s ironic, given our history of supporting paramilitaries in the region. Many of the Central Americans seeking refuge in the U.S. have endured unspeakable violence, much of which can be traced back to U.S. policies in the region during the Cold War. That history has largely been swept under the rug, making it easy for those who traffic in propaganda to absolve America of responsibility and demonize those who have had to bear the fallout of our foreign misadventures. But reality has a way of catching up.

In a few decades, America will be a plurality of racial and ethnic minorities. Immigration policies that emphasize exclusion and enforcement won’t change that inexorable trend. They will only make us less competitive in the global economy, and strip us of any standing to advocate for the rule of law and human rights around the world.

How did life begin? Two common answers come to mind. One is that, at some point, a deity decided to suspend the laws of physics and will a slew of slimy creatures into being. A second is that a one-in-a-trillion collision of just the right atoms billions of years ago happened to produce a molecular blob with the unprecedented capacity to reproduce itself.

UNIVERSE IN CREATION: A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF THE BIG BANG AND THE EMERGENCE OF LIFE by Roy R. GouldHarvard University Press, 288 pp., $24.95

UNIVERSE IN CREATION: A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF THE BIG BANG AND THE EMERGENCE OF LIFE by Roy R. GouldHarvard University Press, 288 pp., $24.95If the first answer fails to convince atheists and agnostics, the second answer feels a like a bit of a letdown. Life on earth was dumb luck, or—depending on how you look at it—a cruel accident. Life might not exist on any other planet, but even if it does—even if there is, say, some creature vaguely resembling a paramecium swimming in a pond on some moon halfway across the galaxy—then there, too, it’s just a freak accident. Or as the great molecular biologist Jacques Monod dourly noted in 1971, “The universe was not pregnant with life, nor the biosphere with man.”

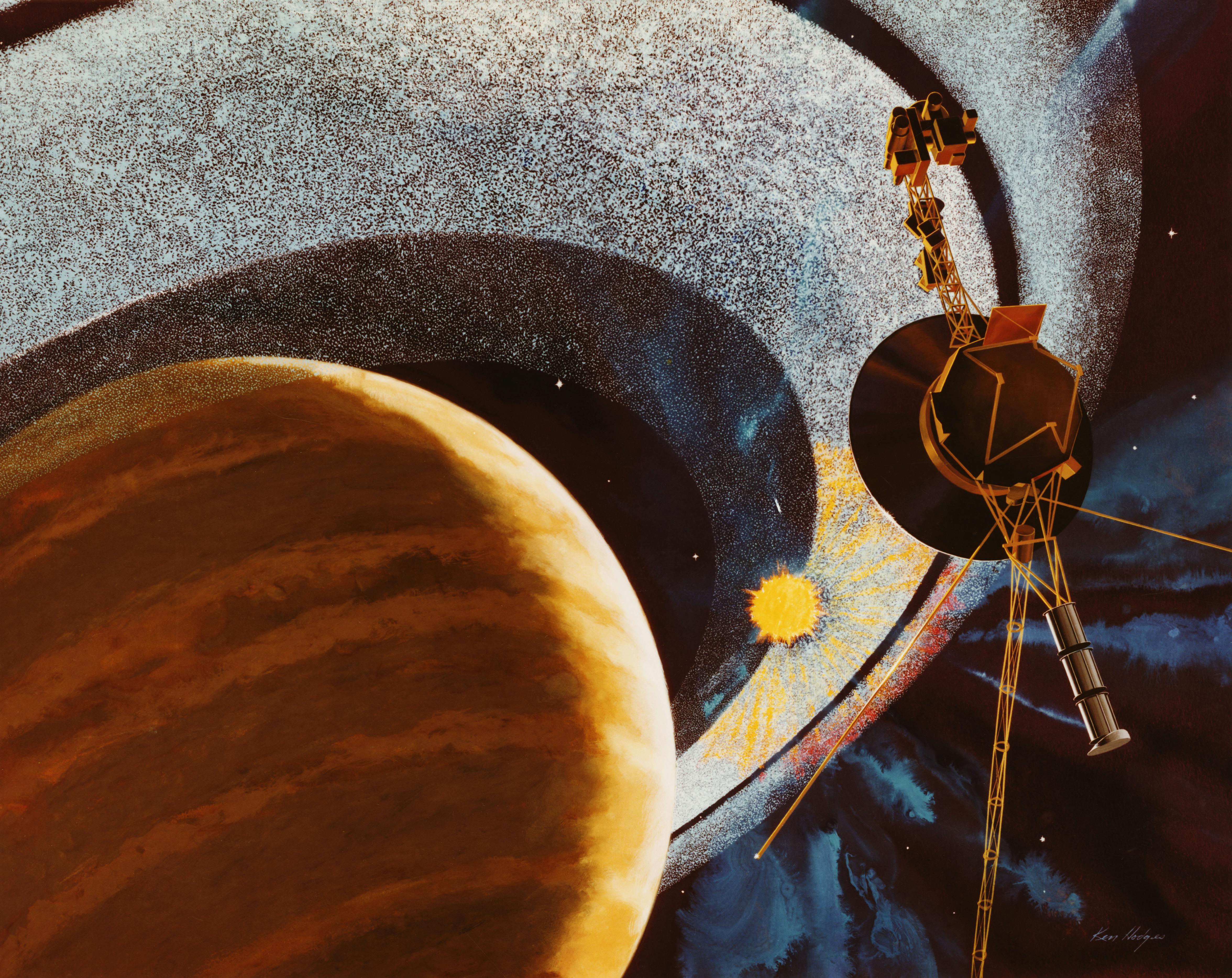

But there is a third possibility. In his new book Universe in Creation: A New Understanding of the Big Bang and the Emergence of Life, Roy Gould, an education researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, argues that life is neither a miracle nor an aberration, but an inevitability whose emergence is dictated by the laws of nature. He frames his book around a question posed by the physicist John Archibald Wheeler in 1983. “Is the machinery of the universe so set up, and from the very beginning,” Wheeler asked, “that it is guaranteed to produce intelligent life at some long-distant point in its history-to-be?”

Gould answers Wheeler’s hypothetical in the affirmative. To do so, he walks us through the history of the universe, making the case that at each step, the “universe’s major construction projects … laid the groundwork for life.” The result is a fascinating synthesis. You have probably heard, for instance, that the universe is steadily expanding. But as Gould describes, it is not growing outward like a balloon, progressively filling up more space around it. Instead, new “universe” is constantly being created, every moment, in the interstices of space and matter. But the manner in which the universe expands, he argues, happens to be optimal for the emergence of life. For instance, it the universe had expanded more quickly, stars would not have formed; more slowly, and hydrogen—a basic component of water and hence life—would not exist. In either case, you would not be reading this paragraph; therefore, the “universe’s infrastructure guaranteed that things would work out properly.”

Gould artfully describes various other highlights in universal history, like the formation of stars and planets. Many of these moments are majestic and hard to visualize, like when stars explode, ejecting their innards throughout the universe, which then, acting under gravitational forces, coalesce into new stars and planets. He describes how under certain conditions all stars will produce carbon, the basic atom of life (at least as we know it). Hence: the laws of nature produce stars, stars invariably produce carbon, carbon is a necessary constituent of life, and ergo, the laws of nature lead to life.

Sometimes, such arguments carry a whiff of tautology: by definition life could not have emerged in the universe if the universe did not provide the preconditions for it do so. But in the final third of the book, Gould returns to answer Wheeler’s question more directly and persuasively, offering “the chief lines of evidence that life really is written into the universe’s building plan.” He notes, for instance that life appeared very soon after the planet’s birth: there are fossils that are almost 4 billion years old, while the earth has only been around for 4.5 billion years. This rapidity suggests a certain inclination towards life, as does the fact that you can find creatures everywhere on the planet, even in its most inhospitable corners, from the bottom of the oceans to, say, a boiling hot geothermal spring.

Life’s machinery is remarkably stable: The same basic genetic code exists in all living things and has survived for billions of years. Other evidence for his thesis includes convergent evolution, which happens when two species independently evolve some similar function or organ. For instance, fish have developed electrical organs—which allow them to do fun things, ranging from shocking their prey to navigating their environment—on six or more distinct occasions in evolutionary history, as Gould notes, which suggests a certain predictability; creatures tend to evolve the same kinds of adaptations when they are presented with particular environmental challenges.

That is to say, life didn’t waste much time in emerging; it occupies

every nook and cranny of the planet; it has a remarkably stable infrastructure

over time and space; and it sometimes evolves in semi-predictable ways towards

common ends. This might indicate, as Gould says, that it “didn’t merely show

up: life seems to belong here.” Fair enough, but this still leaves open the big

question. Why, and how, did life emerge, in the first instance, at all?

When Gould turns to the origin of life itself, his book leaves

somethings to be desired. He largely neglects to discuss competing theories of

the origin of life. He favors the predominant theory, RNA World—even though one could argue that theory contradicts his central thesis. RNA world is

typically explained like this: There are two main genetic molecules, RNA and

DNA. It’s unlikely that life started with DNA, because DNA needs complex

proteins to help it replicate, but complex proteins are produced by DNA. RNA,

however, is a more versatile molecule. It can move around the cell as a

messenger. It can help build proteins. It can even itself function like a

protein, catalyzing chemical reactions—including the replication of RNA itself. It can serve as blueprint, architect,

and contractor, all at once.

Perhaps, then, one day in a primordial pond filled with organic molecules, an RNA molecule came together with the capacity to replicate itself. That would be one of the most consequential half-seconds in the history of the earth (and potentially, the universe): the moment life began. Evolution would take things from there, leading from that single molecular strand to every creature on earth, all of which share the genetic code.

Gould embraces this theory, writing that “an ancient RNA world would make sense … it might have served to jumpstart life.” Yet, as others have argued, the spontaneous emergence of such a highly complex RNA molecule would also have been profoundly improbable. The late Robert Shapiro, professor of chemistry at New York University and author of Origins: A Skeptic’s Guide to the Creation of Life on Earth, has put this eloquently: “The chances for the spontaneous assembly of a[n RNA] replicator,” he wrote in a 2007 article in Scientific American, “can be compared to those of the gorilla composing, in English, a coherent recipe for the preparation of chili con carne.” The unlikeliness of spontaneous RNA replication, then, seems to contradict Gould’s idea that the universe was programmed to produce life. It brings us back to the possibility that yes, life on earth was simply a bizarre, freak occurrence.

And yet—and here’s where things get interesting—Shapiro actually agreed with Gould’s fundamental thesis. He adhered, however, to an alternative to RNA-world referred to as “metabolism first,” which he thought consistent with this thesis. In this framework, molecules—perhaps fats—aggregated and “self-organized,” as they are apt to do under the laws of nature, forming compartments within which metabolic circuits began to run, well before complex genetic molecules come into being. These early forms of life may not have resembled life at all, but perhaps something intermediate between the living and the non-living. “There’s nothing freaky about life,” Shapiro said in a 2008 talk. “It’s a normal consequence of the laws of the universe.” Gould says nearly the same thing—“life really is written into the behavior of molecules.”

Whichever specific origin of life theory we turn to, the thesis that life is somehow programmed into the universe feels uncomfortable but also attractive. Uncomfortable, because it seems to carry a whiff of creationism: Is this just wishful thinking after all, intelligent design gussied up for the scientifically-minded? It is attractive, however, for the same reason. It means that life is the inevitable, invariant consequence of the laws of physics at work, giving life about as much meaning in the universe as an atheist could in good conscience ask for.

What we want to be true is, of course, irrelevant. The fascinating thing, however, is that Gould’s thesis may very well prove true. If it turns out that life—even the most rudimentary microbial life—is common to the universe, the case, as Gould suggests, is settled. Given the distances humans would have to travel to verify this, it is not something that can easily be proved. But even if there is or ever has been any sort of simple life on Mars—and this is something that could be ascertained in our lifetime—then Shapiro and Gould, although they embrace different theories of the origins of life, are essentially correct.

After all, if life emerged independently on two planets in a single solar system, it is nothing unusual. Indeed, that finding alone would be powerful evidence that life has a tendency to emerge, and is presumably widespread throughout the universe. The origins of life would indeed be found in the laws of nature.

But we can’t make too much of that either. For though any such finding would greatly raise life’s stature in the universe, it would do nothing to elevate that of humanity. Even if we prove that life is a property of physics, we humans would still be creatures of chance—and natural selection. Monod would thus be half-wrong and half-right: the universe would indeed have been pregnant with life, but not with humanity.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesThe trick-or-treaters who hit the streets on Wednesday night might spook a few people with their costumes. But the Rainforest Action Network is more freaked out by what’s inside their bags.

On Wednesday, the environmental group sent out a press release accusing four of the world’s largest candymakers of “hiding rainforest destruction in Halloween candy.” Though they’ve all made public commitments to fighting deforestation, RAN said, Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, and Hershey’s are all doing business with a firm that’s bulldozing a tropical rainforest in Indonesia.

Some actually serious halloween candy news — @RAN is accusing candymakers @Nestle, @MarsGlobal, @MDLZ and @Hersheys of using a palm oil supplier that's bulldozing rainforest, "despite all companies having company commitments against deforestation in their supply chains." pic.twitter.com/VLg06PL7FG

— Emily AAAAH-tkin 👻 (@emorwee) October 31, 2018The group’s accusation centers on palm oil. Production of the popular snack food ingredient is among the leading causes of deforestation in Southeast Asia, due to companies bulldozing biodiversity-rich rainforests to build plantations.

One of those companies is PT Surya Panen Subur II. In May 2018, RAN released a report saying the company has been “single-handedly destroying” thousands of hectares in Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem, a critical habitat for endangered orangutans and other species. PT Surya used heavy machinery and fire to clear hundreds of hectares of rainforest illegally from January to March, the report alleged—a practice it had been found guilty of before. The Indonesian government apparently agreed with the report’s findings, as it imposed sanctions on PT Surya in August. But RAN claims the company still supplies palm oil to many U.S. companies, including the candymakers.

Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, and Hershey’s don’t get palm oil directly from PT Surya, RAN notes. They get it from suppliers known to have sourced from the Indonesian company. That contradicts pledges each company has made to stop procuring palm oil that contributes to deforestation. “This is sadly just the latest case of broken promises by these candy companies, in what is now a many years-long struggle to get these companies to take their own commitments seriously,” RAN’s Chelsea Matthews said in a statement.

In response to RAN’s accusation, representatives from both Mars and Nestle said the companies would take action. In an email, a Nestlé spokesperson acknowledged that PT Surya was a “sub-supplier to our direct suppliers in the past,” but added, “We are currently working with our direct suppliers to ensure that they have removed these companies and any others engaged in continued deforestation from our supply chain.” A spokesperson for Mars said the company has “stopped sourcing from PT Surya Panen Subur II given evidence of illegal deforestation.” Representatives of Mondelēz and Hershey’s did not immediately return requests for comment.

Exposure campaigns against big corporations have often worked well for RAN. Since 1987, the group has pressured companies like Burger King, Disney, and General Mills to rid their supply chains of deforestation. These past successes have been partially due to jarring images of endangered species—like orangutans clutching to each other in their bulldozed habitat. People hate the idea of buying products linked to that.

But rainforests do more than just serve as habitats. They prevent the rapid acceleration of global warming by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. That’s an asset the climate can’t afford to lose. Ultimately, the effects from rainforest loss will be far scarier than a Halloween without candy.

This article has been updated to include comment from Mars.

Halloween is a porous time for the American household. Children you’ve never met come all the way up to your door and expect you to open it. You might go to a costume party yourself, slipping into other houses, other masked identities. It’s a rare moment of liberation, and for that very reason Halloween frays the walls of our world. Where the lights in the window ordinarily convey warmth and security, shadows creep in.

A new sequel to Halloween (1978) has just come out, with its original star Jamie Lee Curtis reprising her role as Laurie Strode, only 40 years older. The original movie is often held up as the first true slasher film. Although older films like Peeping Tom and Psycho laid the groundwork for the slasher, its golden age was between 1978 and 1984, which saw the release of classics like Friday the 13th (1980) and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984).

A true slasher film pits a violent maniac, usually male and blade-wielding and unstoppable, against a group of teens who succumb one by one, according to a kind of moral sequence. The slasher may be motivated by a slight or trauma incurred years earlier, springing up to wreak his revenge on a significant anniversary. Halloween is the paradigmatic version of this story, because it takes place so symbolically in the home. Michael Myers, a masked brute, targets babysitters and their friends. No adults can help them, and the family home is no defense against his insidious invasions. Halloween chases a plot up and down the stairs of a house, in and out of closets. It transforms the American home into a chamber of bloody violence.

Some critics have pointed to the rising divorce rate in the 1970s as the catalyst for the slasher film’s rise, reading them as tributes to disenfranchised adolescents’ terror as they come of age without the nuclear family as a protective shield. In a new world of family instability, the horrors of the adult sphere—strangers, stalkers, encroaching death—invade the home. They turn the ordinary travails of every teen—to make a little money babysitting, to have a little fun with your boyfriend—into a battle for survival.

Halloween is also famous for its use of the final girl trope. The term is Carol J. Clover’s, from her 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. The final girl is the last survivor, usually an innocent, white young woman, while all her sluttier or otherwise less virginal friends have already been annihilated. It’s a classic damsel-in-distress role, but inflected by all sorts of gender tension. Is Laurie Strode of Halloween a girl empowered by her own prude boundaries, which gives her the strength to make it out alive? Or is she just a repository of sexist fantasy, the only human being with sufficient “purity” to deserve rescue at the end? A man does usually turn up to save the final girl, after all.

Male violence, the movie seems to say, has this horribly inhuman way of never dying.

Clover’s theory has gained wide application. She herself applied it to Ripley of Alien, because of her “smartness, gravity ... and sexual reluctance,” and others have found final girls in Sarah Connor of Terminator and Sidney Prescott of Scream. But Clover developed the concept very specifically for the classic slasher flick, of which Halloween is the canonical exemplar.

The new sequel, also called Halloween, is a ferocious re-engagement with the final girl concept. We begin with a pair of podcasters who are looking for interviews with the incarcerated Myers and with Strode herself. They find Strode a traumatized grandmother, locked in a fortress of a house and in possession of a poor relationship with her daughter Karen (Judy Greer). Unable to cope with a world still containing a living Michael Myers, Laurie forced Karen to shoot a gun at age 8, to practice facing down a killer who haunted her dreams. Ironically, Laurie ended up perpetuating the trauma of the first Halloween inside her own household.

Her granddaughter Allyson (Andi Matichak) is not so hostile. She has grown up with Karen, who has taught her that the world is actually a safe and loving place. How wrong she is! Inevitably, Michael Myers escapes during a prison transfer. He makes a beeline for the local town, where Halloween is in full swing. It’s 40 years to the day since he first terrorized Laurie. Allyson, along with a gang of other teens, are busy dancing the night away. She loses her phone (actually her boyfriend, dressed as Bonnie to her Clyde, throws it in a trifle) and doesn’t hear the terrible news: Myers is back.

His first victims, hilariously enough, are the podcasters, whom he corners in a dirty toilet and pulverizes with glee. But it’s only with the babysitter that the old Myers really comes out. Sure enough, a little kid complains of shadows in the closet. There’s nothing there, his babysitter reassures him. Suddenly, something is very much there.

Laurie and Karen retreat to the mother’s bastion, while Allyson runs alone through the town. (Allyson’s dad gets killed off instantly, of course.) Once down in Laurie’s basement, we realize that this woman is essentially a doomsday prepper. The cellar is filled with preserved food and weapons. Is this a traumatized victim, or has Laurie morphed into something else—a hateful, isolated old white lady?

The final girl is not what she once was. Though feminist film critics of earlier decades have made much of her plight—and her inversion in tough cookies like Buffy the Vampire Slayer—we live in a different world, now. White women who are loudly afraid of people coming into their homes—mistrustful of the other, homesteading deep down into their notion of American identity—are not sympathetic characters. Would Laurie Strode have voted for Trump? It’s a fascinating character twist. In the 2018 Halloween, the pure white damsel has become a tough gunslinger, but one who feels a little repellent, a little too much like a survivalist in waiting for armageddon. She’s just itching for somebody to step on her lawn.

As Michael stalks through Laurie Strode’s house, she ends up chasing him. Is he in this closet, that looks so like the one she cowered in decades earlier? He eludes her for long, long minutes as she strides with shotgun and torch in a hunt for her own peace of mind. As Laurie passes through each of the upstairs rooms, she seals them off with special portcullis devices. It’s as if she’s compartmentalizing off parts of her own brain.

Allyson makes it to the house, and joins Karen in the basement. Confronted by memories of her own awful childhood, Karen quakes with fear. Here, in a beautiful old house in the Midwest, three generations of women are trapped in a violent manifestation of their shared trauma. Male violence, the movie seems to say, has this horribly inhuman way of never dying.

The last stroke of genius is the movie’s unsatisfying ending. The three women have turned the basement into a trap for Myers, but there’s no way of knowing quite what’s happened to the monster. We do know that Allyson will be scarred forever by her experience; that Karen’s worst girlhood nightmares have come true; that Laurie will never be free of the pain enacted upon her by her would-be killer. Violence doesn’t just come in the night and then leave us, Halloween argues. It gets right down in the basement of your soul, and stays forever.

By stripping Laurie of her purity, the “final girl” of Halloween has been shorn of all her pretenses. White women have become controversial figures in American society—the people we all expected to stand up to a sexual predator in 2016, but who instead came out in droves to vote him into office. Some commentators have condemned these women for their lack of a social conscience. In The New York Times, a number of white women described their vote for Trump as an assertion of their autonomy. “You get through the bad and you focus on the good,” one said. “Basically these were our choices, and I felt he was the better choice, and I had to overlook the negatives and focus on the positives.”

In Laurie Strode, this kind of white woman has found her perfect horror avatar. Laurie refuses to be told what to do, and is full of hatred for the outside world. She cares for nobody but her own offspring, whom she is willing to harm psychologically in order to “save” them. We know that trauma is the reason for her behavior, but Halloween never lapses into a simplistic revenge fantasy against men writ large. Instead, it’s a brutal rumination on intergenerational pain, and the ways that male cruelty can make good women bad. The final girl has become a final woman, and there’s something very nasty in her cellar.

With Election Day approaching, an odd little story from Dodge City, Kansas, made headlines in The New York Times and The Washington Post last week. Local elections officials in the Wild West outpost of yore, now a meatpacking center that’s majority-Latino, had moved their lone voting place outside the city limits, more than a mile from the nearest bus stop, as anti-immigration crusader Kris Kobach—the state elections chief—was fighting off a strong Democratic challenge in his quest for the governorship.

The whole controversy seemed so obviously outlandish—the kind of over-the-top effort to deter voters of color that could only happen in the Deep South or Kobach’s Kansas—that it’s no wonder the story was catnip for national reporters. While another secretary of state overseeing his own election for governor, Kobach’s Georgia ally Brian Kemp, had been garnering scrutiny for months with his massive “purges” of registered black voters, and while reports on the perils of voter ID laws have become numbingly familiar, the Dodge City tale offered a colorful twist on the theme of race-based voter suppression. The Times editors couldn’t resist a cheeky headline for this saga: “To Cast Their Ballots, These Voters Will Have to Get Out of Dodge.”

But the only unusual thing about this story was that it made news at all. Over the past decade, Republican elections officials have been shuttering polling places in minority neighborhoods, low-income districts, and on college campuses at a feverish pace. When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, the U.S. had more than 132,000 polling places; by the time Donald Trump ascended to the White House, eight years later, more than 15,000 of them had been closed nationwide. After 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court basically lifted federal Voting Rights Act oversight from states that were particularly notorious for racial discrimination in elections—including Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, and Texas—the pace of poll closures went into hyperdrive. Thanks to Shelby County v. Holder, if you ran elections in a majority-black county in Georgia, or a booming Latino neighborhood in Houston, you no longer had to ask the Department of Justice to approve a change in where people could vote, or to prove the intent wasn’t discriminatory.

While voter ID laws must be passed by lawmakers, guaranteeing news coverage and public debate, it’s a snap to move or close polling locations. In most states, it can be done unilaterally—all that’s required is a local elections board or official with an eye toward giving Republicans an artificial advantage to seize their chance, and then provide some form of public notice. Closing polls or moving them to white neighborhoods (or all the way out of town) is thus the quietest and least visible form of voter suppression. And studies show that it can be startlingly effective in reducing voting rates—largely at the expense of Democrats. In 2018, this insidious form of targeting poor, black, Latino, and young voters could be the hidden factor in delivering a passel of key elections for Congress and governorships to the GOP—just as it boosted Donald Trump’s presidential bid in 2016.

Stick a pin on any map of marquee midterm races this year, and you’ll find poll closures targeting Democratic voters. A lot of them. Texas, where Ted Cruz is struggling to fend off Beto O’Rourke’s Senate challenge—and where Republicans have long feared the rising tide of young Latinos—has closed more than 400 polling places since 2013, leading the nation in that dubious statistic. Arizona, where Latinos are also threatening the GOP’s hegemony and Democrat Krysten Sinema is neck-and-neck against Rep. Martha McSally for Jeff Flake’s abandoned Senate seat, has closed 200, outpacing Texas on a per capita basis.

In Indiana, where Democratic Senator Joe Donnelly is trying to hold off mini-Trump challenger Mike Braun, more than 20 percent of polling locations have been axed. In North Carolina, Republicans have been more surgical in their approach, zeroing in on toss-up districts like majority-black Mecklenburg County, where young Democrat Dan McCready is trying to wrest away a vacant Republican seat in a tight House race. Mecklenburg is one of six counties in the state in which poll closures reduced black voter turnout by 50 percent or more in 2016.

How about Georgia, where Democrat Stacey Abrams is trying to ride an emerging Democratic majority to victory against Kemp and hasten the end of two decades of white Republican dominance? Surprise, surprise: More than 200 polls have closed since the Roberts Court gave the state a green light to discriminate. And as The Atlanta Journal-Constitution revealed this summer (Kemp’s secretary of state office conveniently keeps no track of the closures), they correlate in near-perfect synchronicity with concentrations of high poverty rates across the state—the places where fewer people have cars to drive to the polls, where public transportation is often non-existent, and where African Americans vote Democratic.

The closures in Georgia could, just as surely as Kemp’s aggressive purges of registered black voters from the rolls, determine the outcome in his dead-heat race with Abrams. This is just pure coincidence, both the secretary of state and local elections officials insist—simply a matter of local Republicans making elections more “cost-efficient” by “consolidating” polling places in more “convenient” white neighborhoods.

But the plague of poll closings in Georgia commenced in earnest in 2015, after Kemp’s office issued a handy guide, formatted Q&A-style, to county officials statewide. Here’s how it starts:

“When should you begin the plan of consolidation or making changes to precincts or polling places?

“Now.”

Twice, the document notes, in bold type: ”As a result of the Shelby vs. Holder Supreme Court decision, you are no longer required to submit polling place changes to the Department of Justice for preclearance.” A particularly helpful section offers advice on how to sell the closures to the public, just in case anybody notices what’s happening before it’s too late to protest: “You can create a professional well thought out presentation,” it says, “showing ... how the changes can benefit the voters and public interest.” Neat!

For every poll closure that raises alarm—before confused voters encounter them during elections, that is—many more of them tend to slip by, unnoticed and unchallenged. This summer in southwestern Georgia, a flap broke out in rural Randolph County, a vast but sparsely populated majority-black (and majority-Democratic) county, where an “election consultant” dispatched by Kemp’s office had advised the local elections board to close seven of nine polling places to save dollars and effort. This would have forced some low-income voters to travel several miles to vote—an impossibility for many, including folks who couldn’t spare so much time away from their jobs or families.

The plan was foiled by sharp-eyed former school superintendent and local Democratic Party chair Bobby Jenkins, who spotted the obligatory notice of the pending change in the fine-print legal notices of the local paper. His discovery led to mass protests and threatened lawsuits from civil-rights groups. Kemp, by then running against Abrams and trying to moderate his hard-won image as a virulent white nationalist, backed down. Which was easy enough, because his consultant had already persuaded ten other low-income counties with large black populations to close polling spots this year alone—on top of the hundreds already eliminated between 2013 and 2016.

Eight of those shuttered polling places are in Macon-Bibb County, where African Americans protested an even more sweeping round of proposed shutdowns in 2015 and warded off a few. Before civil-rights groups found out and raised a fuss, local elections officer Tom Gillon had intended to close 14 of the county’s 40 voting precincts, all in majority-black neighborhoods.

Like his Republican peers across the country, Gillon expressed dismay at the idea that this could be motivated by a desire to create new obstacles for particular voters. “That was the last thing we would consider as a reason for doing that,” he protested. “If the county had more money for us, we’d open up more polling places. We’d be happy to do that, but we have a county government whose budget is very strapped right now.” The intended savings, he said, would amount to $40,000 a year—about $3,000 for every proposed poll closure. The county’s annual budget is $161 million.

Few elections officials are as bracingly honest about their intentions as former Republican legislator Mike Bennett, who became supervisor of elections in Florida’s Manatee County after long lines had discouraged a lot of local voters in 2012. Long lines, often caused by “consolidating” several polling places into one, have been shown to discourage voters just as much as increased distances and lack of transportation. But Bennett set out to make them even longer by closing as many polling places as possible—30 percent of the county’s total. He’d already made his reasoning crystal clear: “Why would we make it any easier? I want ‘em to fight for it,” Bennett said in a 2011 speech, before being term-limited out of the legislature. “I want the people of the state of Florida to want to vote as bad as that person in Africa who’s willing to walk 200 miles.”

Black and Latino voters in Manatee weren’t willing to go to such lengths, as it turned out; a University of Florida study showed that their turnout dropped by 3 and 5 percent, respectively, after Bennett’s mass poll closures.

Back when Georgia started picking off black voters’ polling places in 2013, Stacey Abrams was the minority leader of the state House—and knew exactly what was happening. “If you want to restrict voter turnout in minority and disadvantaged communities, a good way is to move a polling place somewhere they can’t get to,” she said at the time.

Now Abrams, in her epic faceoff against her longtime voting-rights foe Kemp, has to overcome not only this form of voter suppression, but also one of the nation’s most restrictive voter ID regimes and the accompanying scourge of voter purges if she wants to become the first black governor of Georgia. Her campaign has spent a great deal of energy and resources to encourage folks to use mail-in absentee ballots and vote early, to avoid being discouraged by long lines on Election Day. (Abrams herself voted early, driving the point home.)

Democrats in Georgia have responded to the call, voting early in record numbers. Whether that’ll be enough to overcome the advantage Kemp has built in eight years of using every trick in the voter-suppressing book will be revealed on Election Night, when the secretary of state himself will certify a winner in a race that polls show as a statistical tie.

But even if poll closures don’t provide swing-state Republicans the margins of victory they hope for this year, there’s no question we’ll see a whole new raft of them between now and 2020. While some Democrats were slow to catch up to the reality that targeted poll closures can lower turnout just as effectively as voter ID laws, gerrymanders, and voter purges, Republicans have known it and wielded it for years. Indiana’s Republican secretary of state, Connie Lawson—who has unusual power to close local precincts herself—has already announced that she’ll be shuttering a stunning 170 majority-Democratic polling places for 2020 in Lake County, the state’s largest and home to three of its biggest black populations in East Chicago, Hammond, and Gary.

“It is just so Jim Crow,” Carol Anderson, Emory professor and author of a new book on voter suppression, One Person, No Vote, told me recently. “How does this happen without it flaring it up more often as it did in Randolph County in Georgia? It’s the way it’s cloaked in legalese, buried in the local newspaper, looking to anyone who happens to notice it like just another routine bureaucratic change.

“When we think about old-style voter suppression,” Anderson continued, “we often think about the violence, the clash on the Pettus Bridge, the murders of folks like Herbert Lee and Louis Allen, who were working to get people to register to vote. But Jim Crow operated under the legal system. That’s what we miss. The laws, the poll taxes, the literacy tests—they all had the aura of legitimacy. What we have today, with poll closures done in the interest of ‘streamlining’ and ‘saving taxpayer money,’ is no less pernicious. And no less pervasive.”

It’s less than a week until Election Day, and Donald Trump is scared. Most polls indicate that Democrats are poised to retake the House of Representatives. From there, they’ll be able to unleash a wave of oversight investigations into scandals that his Republican allies in Congress have largely squelched or ignored. It’s less likely that Democrats will also win back the Senate, but if so, they’ll have veto power over every one of Trump’s judicial and executive nominees until 2020.

Republicans are struggling to make the case for retaining power after two years of unified control of the government. The president’s party usually loses seats during the first midterm election, and the unpopularity of both Trump and the GOP’s legislative agenda isn’t helping. Not only did the Affordable Care Act largely survive an all-out push to repeal it, but many Republican lawmakers are now being forced to defend their votes to strip coverage requirements for people with pre-existing conditions. Most voters also rightly think that the GOP’s tax-cut package, once touted as a near-certain midterms boon, was simply a handout to the rich and powerful.

Thus, Trump is trying a different message with voters: a virulent mélange of nationalism and authoritarianism, largely centered on the caravan of several thousand migrants traveling toward the U.S. from Central America. He has likened the caravan to a foreign “invasion,” and is using it to justify extraordinary measures. He ordered more than 5,000 troops to the border with Mexico on Monday, though their mission is limited and largely theatrical. He’s also reportedly mulling an executive order to close the southern border to asylum-seekers.

Then came Tuesday’s news. Trump is considering an executive order that would unilaterally reinterpret the Fourteenth Amendment to scrap birthright citizenship, a bedrock principle of post-emancipation American democracy. “It was always told to me that you needed a constitutional amendment,” he told a reporter. “Guess what? You don’t.”

Elected officials have a habit of over-promising and under-delivering during campaign season, but Trump’s moves over the past two weeks go far beyond that. He’s deployed the military within the U.S. against a phantasmal threat. After one of his supporters was arrested for sending mail bombs to his political adversaries, the president responded by warning that he “could tone up” his rhetoric even further. Now he’s asserting the power to single-handedly narrow the definition—and thus the protections—of American citizenship. In effect, Trump is posing a question to the American electorate: What level of racist authoritarianism are you willing to accept?

Any attack on birthright citizenship in particular should set off klaxons about American democracy. Republican politicians have long railed against the practice because it also applies to undocumented immigrants who have children on U.S. soil. During the 2016 elections, multiple GOP presidential candidates suggested that they could take steps to curtail it in some fashion through legislation. Michael Anton, a former Trump national-security aide, took it a step further earlier this year by asserting in a Washington Post op-ed that the president could instruct the federal government to disregard birthright citizenship by executive fiat.

Anton is not a legal scholar, and it showed. The Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause is short and unequivocal: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Anton argues that undocumented immigrants don’t qualify because they are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. But legal scholars widely agree that that provision was meant to exclude the children of foreign diplomats, who enjoy immunity from U.S. laws and therefore aren’t generally subject to federal jurisdiction.

Another argument raised by Anton is that the Fourteenth Amendment’s drafters never meant for the Citizenship Clause to apply to undocumented immigrants in general. Their conversations during the ratification debate suggest otherwise. “Nothing in text or history suggests that the drafters intended to draw distinctions between different categories of aliens,” former Texas Solicitor General James Ho wrote in a 2006 analysis of the drafters’ views of the clause. “To the contrary, text and history confirm that the Citizenship Clause reaches all persons who are subject to U.S. jurisdiction and laws, regardless of race or alienage.” Ho is no left-wing firebrand, either: Trump successfully nominated him to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals earlier this year.

Many portions of the Constitution are subject to considerable debate and interpretation by the American legal community. The Citizenship Clause isn’t one of them. In the 1898 case U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court ruled that the son of two Chinese immigrants who was born on U.S. soil had automatically received American citizenship at birth, even though the Chinese Exclusion Act meant that his parents could never acquire it themselves. That ruling remains the law of the land 120 years later. No subsequent ruling has challenged its expansive view of the clause, and few legal scholars have ever disputed the prevailing consensus on it.

Beyond the flawed legal arguments is a much more disturbing perspective on American citizenship. The Citizenship Clause was partially designed to overturn the Supreme Court’s notorious 1857 ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which held that descendants of African slaves could never become U.S. citizens. The Radical Republicans who drafted the Fourteenth Amendment hoped to build a truly multiracial democracy on the ashes of the slaver aristocracy that had lost the Civil War. They sought to roll back racist state laws passed after emancipation that tried to restore the old order with a new face. The Fourteenth Amendment exists to ensure that American citizenship is forever removed from the realm of public debate, that its rights and protections would never again depend on the fleeting whims of a transitory electoral majority.

Establishing a universal baseline for citizenship pushed the country far closer toward the ideal of an American citizenry that transcends race, class, and caste. Trump and his allies are hostile to that notion, to say the least. As president, he’s made common cause with white nationalists and embraced a blood-and-soil view of nationality. It’s no secret that Trump’s immigration policies are rooted in antipathy for non-white immigrants. “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” he allegedly asked lawmakers in January at the White House in January when they discussed deportations for long-term immigrants from Haiti and some African countries. “Why do we need more Haitians?” Trump added. “Take them out.”

In this worldview, a caravan of migrants fleeing violence and hardship in Central America isn’t a test of America’s compassion or even just a matter best handled by existing asylum laws. It’s a demographic threat to the American polity. Trump and his allies have instead wielded every ancient trope used to denigrate would-be immigrants. Fox News hosts and guests have wondered aloud if they would bring infectious diseases into the country. Trump baselessly asserted that there were “some bad people” among them, including “hardened criminals.” He also warned about the presence of “unknown Middle Easterners,” an apparent racist shorthand for terrorists, before later admitting he had no proof. (Reporters on the ground with the caravan have described a diverse, unthreatening crowd of men, women, and children of all ages.)

Inflaming these hatreds can have deadly consequences. In recent weeks, Republican lawmakers and the conservative media ecosystem pushed a narrative that the caravan had been encouraged by Democratic officials, liberal activists, and billionaire investor George Soros to disrupt the midterms. Last week, federal agents arrested an ardent Trump supporter who allegedly sent mail bombs to Soros, the homes of two former presidents, and almost a dozen other political adversaries of the president. On Saturday, a white-nationalist gunman in Pittsburgh posted online that he “couldn’t sit by” while a Jewish nonprofit group continued to “bring invaders in that kill our people.” He then stormed into a nearby synagogue and killed eleven people.

The wave of violence and attempted assassinations have not deterred Trump. If anything, he’s grown bolder in his efforts to impose a narrower, ethnocentric vision on the bounds of American civic life. By insisting that he can revise the Constitution’s definition of citizenship through an executive order, the president is assuming unprecedented authority to decide who is and isn’t an American. Next week’s elections will technically determine the future composition of the House, the Senate, and of state governments. They may also decide the future composition of America itself.

No comments :

Post a Comment