It’s been five years since Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of Facebook, published her manifesto, Lean In, urging women not to sell themselves short at work or doubt their ability to balance a family with a career. Though controversial, the book was a mega-bestseller, selling more than four million copies. It spawned a mini empire, with 40,000 mentoring circles and annual campaigns, and turned Sandberg into a celebrity executive: the face of a new brand of professional feminism.

Lean In was published when Sandberg was 43, and capped her impressive rise in the professional world. She began her career working closely with her mentor, Larry Summers, who taught her at Harvard. She worked with him at the World Bank and, later, at the Treasury Department. From there she went to Google, where she led the company’s online advertising efforts. In 2007, Sandberg met Mark Zuckerberg at a Christmas party, and he convinced her to jump ship.

The Facebook founder tasked Sandberg with a daunting goal: Make the company profitable. It took her just two years to do so. In 2017, Facebook made in $40 billion in advertising revenue, and today the company’s market capitalization is $400 billion. Sandberg also brought a corporate professionalism to the company. If Zuckerberg was the baby-faced tech visionary, Sandberg was lead adult in the room, taking care of Facebook’s economic and political needs. She has been so successful that she was rumored to be the frontrunner to lead the Treasury Department if Hillary Clinton had become president.

That sterling reputation took a serious blow this week. A report from The New York Times shows that, while Sandberg was building her global brand, she was using aggressive and underhanded tactics at Facebook. As the company faced increasing criticism and pressure over its handling of fake news, election interference, data abuse, and the incitement of ethnic violence and genocide, she embraced a strategy to suppress information about Facebook’s problems, discredit its critics, and deflect blame onto its competitors. She berated her security chief for being honest about the extent of the Russian campaign on the site. And she employed multiple crisis PR firms that spread fake news as a defense tactic, in one instance tying critics to the liberal billionaire, George Soros, a frequent subject of anti-semitic abuse online.

Sandberg leaned in, and then started throwing sucker-punches—a revelation that undermines the myth she spent years building about herself.

Before Sandberg’s arrival at Facebook, Zuckerberg was almost single-mindedly focused on the user experience. “There remained a profound corporate ambivalence toward advertising as the means for Facebook to become a real business,” David Kirkpatrick wrote in The Facebook Effect. But under Sandberg, targeted advertising became the company’s central focus and source of revenue.

“From the moment she arrived, Sandberg was the company’s top advertising champion and salesperson,” he wrote. “She had immense experience with advertisers from Google and a deep appreciation of the importance and potential of ads on the Net. According to some at Facebook, in her first weeks there was hardly anyone else at the company about whom the same could be said.” Facebook became profitable for the first time in 2010, and as it grew into one of the most powerful and profitable tech companies in the world, Sandberg received much of the credit.

Having turned Facebook into a money-making enterprise, Sandberg took over the reins from Zuckerberg, who increasingly spent time on extracurricular activities like last year’s “listening tour” across America. The Times’ portrayal of her leadership in his absence is damning. Its report opens with her “seething” over the fact that the company’s chief security officer, Alex Stamos, told its board that it had yet to deal with all of the Russian activity on its platform. “You threw us under the bus!” she reportedly yelled at him. (Stamos has since left the company.)

Sandberg played a central role in nearly every misdeed at Facebook that’s described in the Times piece. Singularly focused on the company’s stock price and its advertising-based business model, she worked to minimize data abuse and election interference. She employed a Republican-leaning crisis PR firm to attack the company’s critics, and opted to do little to address the company’s rampant fake news problem, fearing that it would anger conservative users.

Sandberg also hired lobbyists to pester Democratic senators who dared criticize the company and its business model, and to push terrible pieces of legislation like the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, which has endangered the safety of sex workers, in an attempt to woo skeptical Republicans. She worked to minimize regulation that could have helped the company fight bad actors, but would damage its business model. “While Facebook had publicly declared itself ready for new federal regulations, Ms. Sandberg privately contended that the social network was already adopting the best reforms and policies available,” the Times reported. “Heavy-handed regulation, she warned, would only disadvantage smaller competitors.”

This was, to an extent, what Sandberg was hired to do: grow the business, protect the bottom line, and avoid onerous regulation. Using dirty tactics to accomplish these goals is a widely accepted practice in corporate America. But Zuckerberg and Sandberg have repeatedly insisted that they were new kinds of executives leading a new kind of company. When Facebook hit a snag in the past, they beseeched their users—a significant percentage of the public—to trust them.

It’s unclear if Sandberg thought that she would get away with, for instance, smearing critics by associating them with Soros. Zuckerberg told reporters on Thursday that he and Sandberg were not aware of the actions being taken by the PR firms employed by Facebook. Sandberg released a statement on Facebook on Thursday in which she also denied that she attempted to block investigations into Russian interference.

“On a number of issues—including spotting and understanding the Russian interference we saw in the 2016 election—Mark and I have said many times we were too slow,” she wrote. “But to suggest that we weren’t interested in knowing the truth, or we wanted to hide what we knew, or that we tried to prevent investigations, is simply untrue. The allegations saying I personally stood in the way are also just plain wrong. This was an investigation of a foreign actor trying to interfere in our election. Nothing could be more important to me or to Facebook.”

But what did Sandberg expect when she hired a Republican opposition-research firm? It was a short-sighted response that will have long-term consequences, for both Facebook and Sandberg. In her Facebook post, Sandberg denied any knowledge of the company or its work. “I did not know we hired them or about the work they were doing, but I should have,” she wrote. “I have great respect for George Soros—and the anti-Semitic conspiracy theories against him are abhorrent.” But the damage is done. “Now we know Facebook will do whatever it takes to make money,” Rishad Tobaccowala, chief growth officer for the Publicis Groupe, told The New York Times. “They have absolutely no morals.”

Sandberg and Facebook could have opted for a different strategy, one that embraced transparency while the company explored business models that would leave it less vulnerable to misinformation campaigns, fake news, conspiracy theories, and political division in general. But she opted for a shadowy, bare-knuckled fight to protect the company’s lucrative advertising business. In the process, she made it clear that she was just another cutthroat executive leading just another cutthroat company.

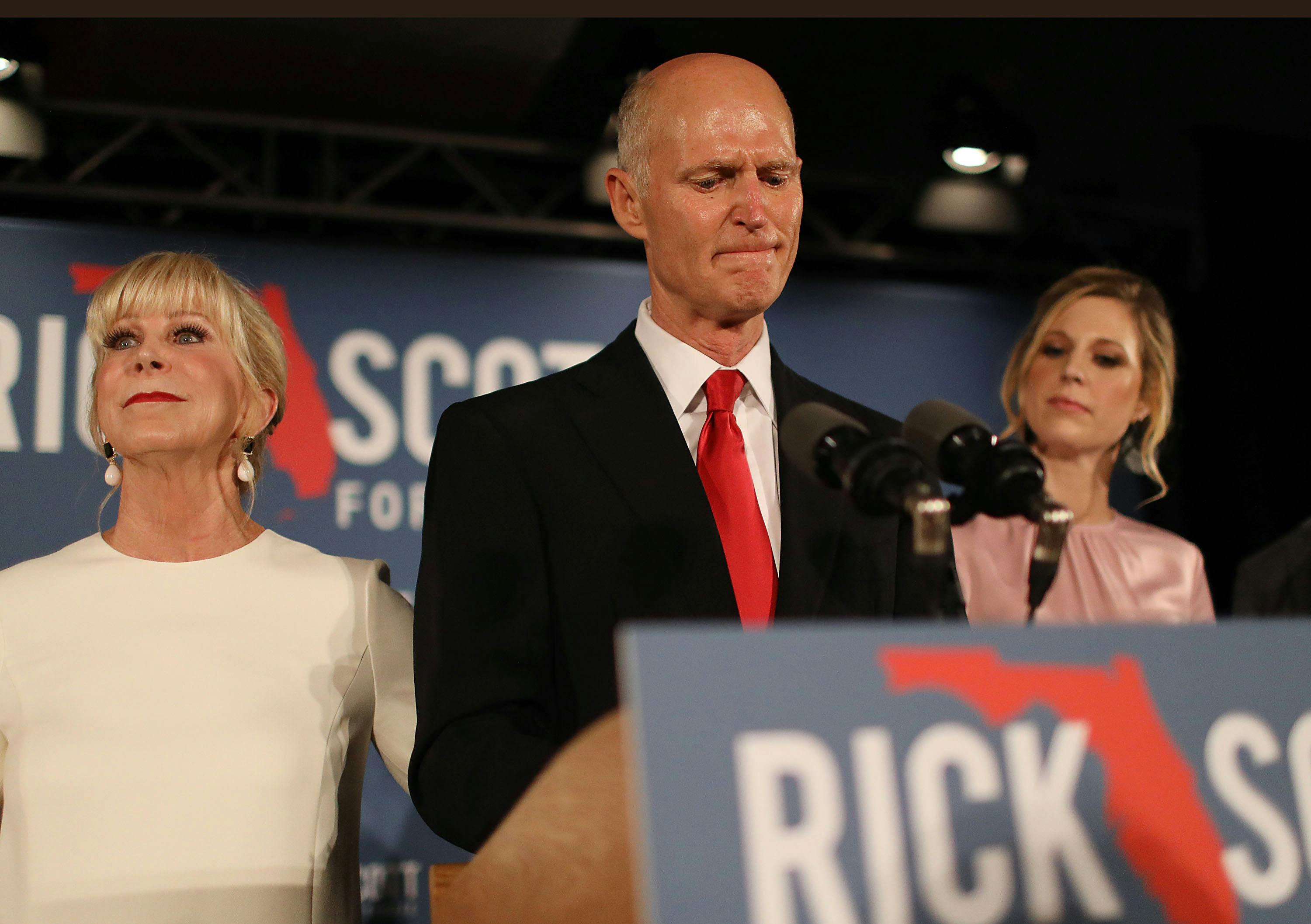

What was your signature like at eighteen? Is it still the same? In the wake of the 2018 midterms, the American electoral system is under scrutiny again—as, in fact, it seems to be almost every two years now. This year, razor-thin margins in Florida and Georgia are drawing fresh attention to allegations of voter suppression and incidents of electoral mismanagement. And now, the recount in Florida has given absentee voters until Saturday to make sure that ballots originally thrown away are counted.

Florida, Georgia, and Rhode Island are three out of several states still requiring a signature match for absentee voters. In practice, what that means is letting election officials check the signature somewhere on the absentee ballot against the signature on an application or a form of government ID. Over the past year, judges in California and New Hampshire have struck down the requirements, declaring they unconstitutionally deprived voters of their right to cast a ballot and have it counted. The process’ implementation in other states is also raising alarms. Among other problems, the policy places a disproportionate burden on voters with disabilities, elderly voters, and others. It’s also strikingly unnecessary and unscientific.

It’s reasonable to try to make sure that the person who casts an absentee ballot is the same person who applied for it. One doesn’t need to be a handwriting expert, though, to see why signature-match laws could be problematic. A person’s signature often changes throughout their life, and in hasty circumstances a well-crafted one can be abandoned in lieu of a scrawled scribble. When it comes to electronic signature pads, all bets are off—as anyone who’s ever seen their own baffling jottings on one of those devices well knows. Nonetheless, Florida election officials use signatures taken from those pads while at the state department of motor vehicles as the basis for comparison to a print signature on Election Day.

Their determinations could have an impact on two major races. Florida Governor Rick Scott is ahead by a narrow margin in his battle to unseat Senator Bill Nelson, with just over 12,000 votes separating the candidates. State officials are conducting a manual recount in the Senate race, giving voters until Saturday to fix their mismatched signatures—a hurdle they shouldn’t have to cross in the first place.

It’s not immediately clear how nationally widespread the problem is. America’s balkanized election system has some benefits. The lack of any centralized structures makes it somewhat resistant to large-scale rigging, for example. But there are also drawbacks. It’s not immediately apparent how many states use signature-matching laws. There can also be significant differences in how the laws are implemented from state to state. What seems clearer is that the requirements run the risk of tossing out valid, legitimately cast votes.

In New Hampshire, for example, absentee ballots are scrutinized by a local official known as a moderator, who is elected for a two-year term and operates independently from the secretary of state’s office—the office in New Hampshire (and most states) that oversees elections. On Election Day, the moderator publicly (i.e. in front of witnesses and reporters) checks the signature on the absentee ballot envelope—which in New Hampshire is a piece of paper doubling as an affidavit, with the actual ballot and vote inside. If he or she thinks it doesn’t match the one on the application form for the absentee ballot, the envelope is left unopened and the ballot isn’t counted. Their decision effectively nullifies that person’s vote.

The American Civil Liberties Union challenged the state’s law in 2017 on behalf of three New Hampshire voters who were disenfranchised during the 2016 election. One of them, Mary Saucedo, was 94 years old at the time. Advanced macular degeneration has left Saudeco legally blind, and she told the court that she filled out her ballot with the assistance of her 86-year-old husband. He filled out the absentee ballot request form on her behalf, and when her signature on the envelope didn’t match the one on the form, it was rejected on Election Day.

“There is no procedure by which a voter can contest a moderator’s decision that two signatures do not match, nor are there any additional layers of review of that decision,” Judge Landya McCafferty wrote in her August ruling blocking the law. “In other words, the moderator’s decision is final. Moreover, no formal notice of rejection is sent to the voter after Election Day.” New Hampshire voters whose absentee ballots are rejected can only find out by checking the secretary of state’s website after voting has already concluded. The site removes the information after three months.

A California state court blocked a similar law earlier this year with relative ease. State officials tried to contend that the provision had only prevented roughly 45,000 voters from casting a ballot, a group larger than the number of seats in San Francisco’s Pac Bell Park. But the judge concluded that it still violates the Constitution’s due-process requirements because it did not give those affected a chance to respond.

The impact is particularly acute in Florida because its elections are often decided by extremely close margins.“The statute fails to provide for notice that a voter is being disenfranchised and/or an opportunity for the voter to be heard,” Judge Richard Ulmer wrote in his ruling. “These are fundamental rights. The parties consume considerable ink disputing what test to use in determining unconstitutionality, but [the provision] does not pass any test cited.”

In Georgia, the epicenter of voting-related controversies this election cycle, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order in October that barred state officials from tossing out ballots with signature mismatches. Instead, they became categorized as provisional ballots. The court ordered that voters be given notice that their ballot was being questioned as well as an opportunity to quickly remedy the problem in person after Election Day. A Washington Post analysis published on Friday found that the bulk of the statewide rejections are coming from a single Georgia county, which may suggest that state laws are being enforced unevenly.

Florida may be the most dramatic example of all. Tens of thousands of ballots in the state are in bureaucratic purgatory at the moment thanks to the state’s signature-match requirements. The impact is particularly acute in Florida because its elections are often decided by extremely close margins. Though the state’s 2018 results aren’t yet finalized, fewer than a hundred thousand votes have separated the first- and second-place candidates in both the Florida governor’s race and the U.S. Senate seat race in recent days.

This problem isn’t new for the state, either. According to Mother Jones, Florida officials rejected 24,000 ballots in 2012 and 28,000 ballots in 2016 for purportedly mismatched signatures. (Since the state is still undergoing a manual recount, it’s unclear how many ballots will ultimately be rejected this cycle.) The state offers voters the opportunity to “cure” the problem by showing up in person at state election offices to correct any errors, but the magazine reported that younger and minority voters were less likely to follow through on those offers.

Signature-match laws fall within a broader spectrum of measures that can deprive voters, based on small errors, of their electoral influence. Under Secretary of State Brian Kemp, Georgia tried to freeze voter-registration applications if they did not precisely match state databases, even if the difference was a mere comma or hyphen. A state judge also ordered Georgia earlier this week to not certify its election results until it counts ballots that had been excluded because the voter did not list his or her date of birth. Stringent measures like these are often justified by supporters as being necessary to thwart voter fraud, which is virtually nonexistent. Their practical impact appears to be disproportionately excluding lower-income voters or those from disadvantaged communities, who may lack the resources to contest their disenfranchisement.

Most of the discussion surrounding the integrity of the voting process this year focused on figures like Kemp and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach—both of whom have been accused of voter suppression—or on sweeping measures like voting-roll purges or voter ID laws. But voter rights aren’t always denied by heavy-handed tactics or blatantly discriminatory laws. Sometimes the most insidious threat to the franchise comes from a thousand bureaucratic cuts.

To stop kids from smoking, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb wants to stop nicotine from tasting like candy. So he proposed two new restrictions on cigarette and e-cigarette products on Thursday.

One proposal, which has dominated the media coverage, would make flavored e-cigarettes—also known as vape pens, or vapes—much harder to access. Gas stations and convenience stores would only be allowed to sell tobacco- or menthol-flavored vapes, since those are often used by cigarette smokers who are trying to quit. Vape flavors like cotton candy and raspberry would be relegated to “age-restricted, in-person locations” such as liquor stores and specialty tobacco shops. Online sales would be more closely monitored.

The announcement is already having an impact: Juul, the market leader in e-cigarettes, announced that it will stop selling most of its flavored products in stores.

Gottlieb’s other proposal has drawn less attention, but is more controversial: an outright ban on menthol cigarettes. “I believe these menthol-flavored products represent one of the most common and pernicious routes by which kids initiate on combustible cigarettes,” he said in his statement.

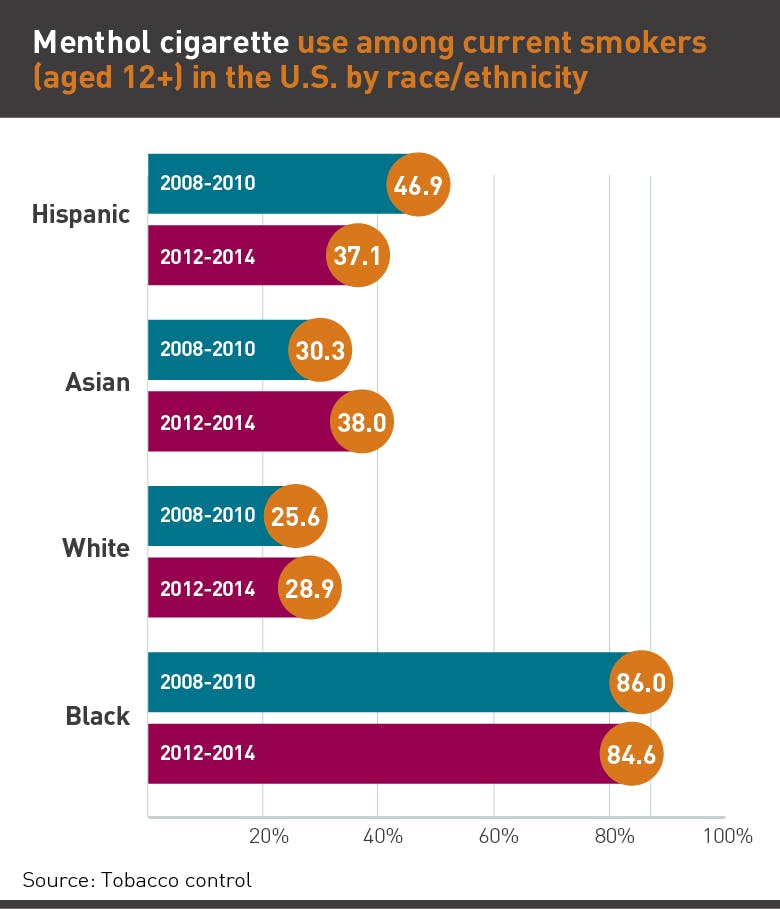

Young people have been shown to be more likely to try a menthol cigarette over a regular one, since the minty flavor masks tobacco’s harsh taste. But young Americans aren’t the predominant smokers of menthol cigarettes. Black Americans are. According to Truth Initiative, a non-profit tobacco control group, nearly 85 percent of black smokers prefer menthol cigarettes, compared with only about 29 percent of white smokers. So Gottleib’s announcement caused some on Twitter to wonder: Is the proposed ban racist?

truthinitiative.org

truthinitiative.orgThe question is not a new one. It came up frequently in 2010, when the FDA was considering a similar ban. Though it eventually failed, that proposal “caused a rift among forces that advocate on behalf of blacks’ interests,” NPR contributor Deron Snyder wrote at the time. Groups like the NAACP and the African Tobacco Control Leadership council were supportive, saying it would reduce rampant health problems in the black community. Groups like the National Black Chamber of Commerce, however, saw the ban as a racially targeted infringement on black smokers’ freedom of choice. “Menthol simply is a taste preference preferred by African Americans and it should not be singled out for a ban,” the group’s co-founder Harry Alford said in 2011.

Snyder agreed. “Why would the government ban the cigarettes that I prefer, while the estimated 78 percent of non-Latino, white smokers who prefer non-mentholated cigarettes are allowed to keep on puffing?” he wrote, adding that a cigarette ban should not be applied unless all cigarettes were banned. Reason magazine made a similar argument in 2017, as several cities passed ordinances banning the sale of menthol products. “It is true that black smokers use menthol cigarettes at a greater rate than the average American smoker,” Christian Britschgi wrote. “But does that mean the proper anti-racist response is to crack down on menthol? Indeed, is it not perhaps a tiny bit discriminatory to prohibit a product primarily because of the race of the people buying it?”

Proponents, however, argued that banning menthol cigarettes is actually an anti-racist policy—a way to combat the tobacco industry’s racist marketing strategies. “Cigarette companies know that most African-American smokers prefer menthol cigarettes and they exploit this preference in their marketing efforts to African Americans, in general, and to African-American kids, in particular,” the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids wrote in a memo that compiled research on the subject.

It’s true: Menthol cigarettes are disproportionately advertised in predominately black communities, and the ads in those communities are disproportionately directed at young people. A 2010 study by the Harvard School of Public Health comparing tobacco marketing in two racially disparate neighborhoods found that the predominantly black one “had more tobacco retailers, and advertisements were more likely to be larger, promote menthol products, have a lower mean advertised price, and occur within 1000 feet of a school” than the predominantly white one.

That strategy has had profound consequences for the health of black communities. Smoking-related illness is the largest cause of preventable death among African Americans—more than homicides or even car accidents. According to the CDC, “Although African Americans usually smoke fewer cigarettes and start smoking cigarettes at an older age, they are more likely to die from smoking-related diseases than Whites.” It’s not clear why that is, but the CDC notes that black smokers are less successful at quitting cigarettes than other ethnic groups. Menthol cigarettes also have been shown to be harder to quit than regular ones.

Further complicating the debate, tobacco companies have given millions of dollars to black organizations and politicians. The National African American Tobacco Prevention Network referred to it in 2015 as the industry’s “informal mutual aid pact with some black organizations,” including the NAACP and the United Negro College Fund. In return for donations, “some of the groups have helped the industry fight anti-smoking measures. Other times, critics say, they have simply turned a blind eye to the harmful impact of tobacco on the black community.” A Mother Jones investigation from 2015 found that “half of all black members of Congress received financial support from [tobacco company] Lorillard, as opposed to just one in 38 nonblack Democrats. To put it another way, black lawmakers—all but one of whom are Democrats—were 19 times as likely as nonblack Democrats to get a donation.”

With a menthol ban in the offing again, these relationships are sure to see renewed scrutiny. But Gottlieb has made clear where he stands. “I believe that menthol products disproportionately and adversely affect underserved communities,” he said in his Thursday statement. “And as a matter of public health, they exacerbate troubling disparities in health related to race and socioeconomic status that are a major concern of mine.”

When Amazon announced on Tuesday that it would build one of its new headquarters in Long Island City’s Anable Basin, environmentalists were quick to notice that the site could be partially underwater by 2050. By the next millennium, it will be completely submerged, according to the environmental research group Climate Central’s most recent projections. Situated in an inlet along the East River, the site is currently home to parking lots and warehouse spaces, but when Amazon breaks ground, which could be as soon as 2019, new apartment complexes and office buildings will go up—all of which would be vulnerable to flooding if sea levels rise even just a few feet.

After Hurricane Sandy battered the East Coast in 2012, New York City adopted new building codes to help minimize the damage of such flooding. Today, developers working in flood zones are required to elevate their buildings above the anticipated water level in a storm. An additional set of guidelines for waterfront developers recommends that they build floodgates and levees, create wetlands and barrier islands, and elevate surrounding land to address flooding and erosion. But these recommendations are nonbinding—it’s up to developers to decide whether or not they want to put up the money to build such green infrastructure.

For Amazon, this means that any attempts to shore up its Long Island City site will have to be entirely on its own steam. Before deciding to split its new headquarters between New York City and Northern Virginia, the company considered several HQ2 locations vulnerable to flooding, including Miami, Newark, and Boston, without making any public statements about how it would adapt to rising tides. Then, on Tuesday, the company agreed—in lieu of property taxes—to offer New York City a series of payments, earmarked for infrastructure improvement (streets, sidewalks, utilities, transportation, schools, and the like). Among the priorities listed on its Memorandum of Understanding with the city was “environmental remediation,” the closest Amazon has come to displaying an interest in the environment. As yet, the company has not released any details on what types of projects might be included in this category.

If history is any guide, however, Amazon will protect itself without thinking of the surrounding neighborhood. Too often, said Amy Chester, the managing director of the collaborative research and design group Rebuild by Design, developers only build barriers to climate change around their own sites, ignoring neighboring areas that are at risk. “What you end up having is islands of protection,” she said. Meanwhile, nearby houses and businesses are often left even more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. “If a developer is protecting its own site, where is that water that it’s displacing going to go?” said Linda Shi, an assistant professor at Cornell’s School of Architecture, Art, and Planning who studies urban environmental governance. “It’s going to go to the many places that don’t have elevated buildings and flood walls.”

Over the last ten years, South Boston, for example, has witnessed an explosion of development in its Seaport District (including a brand new Amazon office expected to house 2,000 workers), an area that is projected to be underwater within the next century. Developers there have responded to the threat by fortifying their towering office buildings and hotels with inflatable or storable floodwalls. Then, last March, when a Nor’easter inundated Boston with the third highest storm surge on record, streets throughout the Seaport and in nearby South Boston filled with water. That hasn’t stopped developers elsewhere from leaning on floodwalls for protection, though. In Florida, about 64,000 homes will experience repeated flooding just from high tides within 30 years. There, too, owners are erecting portable walls to keep water off their properties. In Queens’s furthest southern reaches, just twenty miles from Amazon’s Long Island City site, luxury real estate developers—such as JDS, whose Saltmeadow project broke ground in 2015, just three years after Sandy—are building their electrical utilities and apartments above ground level, which is enough to meet the New York City guidelines passed after Sandy, but not enough to offer any protection to its neighbors further inland.

“Just go around the harbor,” said Roland Lewis, president and CEO of the Waterfront Alliance. “Red Hook is as vulnerable as it was when it was devastated by Sandy, the Rockaways are a little bit better but not much.”

While it’s still unclear what—if anything—Amazon plans to do to shore up its new site, what is clear is that simply building floodwalls, or agreeing to build above ground, is insufficient. A better adaption model exists just a little further down the East River, however. In Hunter’s Point South, the city has planted more than an acre of wetlands modeled on the ones that existed there 200 years ago, before the New York Daily News, along with some sugar and railroad companies, set up shop on the site. The native flora is designed to absorb and gently release storm water back into the river. Further south, in Williamsburg, at the site of an old Domino Sugar refinery, a private real estate development firm, Two Trees, also recently invested $50 million into a public park elevated above the floodplain.

There are similar plans in the works in Long Island City; the developer of a site just to the north of Anable Basin, TF Cornerstone, which was recently brought on as a partner on the Amazon project, has proposed rezoning the site to include a park, built in the floodplain, which would protect against shoreline erosion using tools such as bioswales to retain runoff water. Of course, it’s still unclear whether the park will actually be built now that Amazon is moving its HQ2 there, and even if it is, such an investment would put only a small dent in the massive unfilled need for coastal protection.

In this, the fight over Amazon’s new site has lessons for the developers and urban planners working in places vulnerable to climate change. Waterfront development is surging across the country, particularly in dense cities like New York where outmoded industrial waterfronts offer some of the only large spaces for new development. Meanwhile, according to Robert Freudenberg of the Regional Plan Association, which does independent research and advocacy on urban planning issues in the Tri-state area, “Private capital flows into new development and new parks, and meanwhile existing neighborhoods stay at lower levels of adaptation and innovation.”

It’s often said that climate change and environmental risk disproportionately impact poorer people and minorities. Low-income and minority families are more likely to live closer to dangerous industrial facilities, leading to a range of health complications. (Black children are, for example, twice as likely to have asthma as white children and ten times more likely to die of complications from asthma.) They are also more likely to live in flood-prone areas with deficient infrastructure. But the role private companies play often goes unnoticed: Because funds for resilience at the city, state, and federal levels are limited, developers are left to dictate which parts of the city will be protected from environmental harm and how. Amazon is currently in this position, and unless it takes its responsibly seriously, it is only going to be part of a much larger problem.

“We tend to think about private sector adaptation primarily at the scale of individual properties,” Shi said. “But if you’re thinking about the longer term future, the threat is at such a magnitude of scale, it really is a collective action problem.”

No comments :

Post a Comment