Last night, more than 100 protesters occupied the downtown Santa Monica offices of The Blackstone Group, a real estate and private equity giant that spent millions of dollars to defeat a ballot measure on Tuesday to expand the ability of localities across California to enact rent control. Standing under a banner reading “Governor Newsom Don’t Let Blackstone Hijack Our Communities,” one tenant said she had to fight an unjust eviction by her landlord Invitation Homes, a subsidiary of Blackstone. “Prop 10 didn’t fail because the problem isn’t real or because voters don’t support rent control,” she said. Rather it failed because of harsh attacks by Blackstone and other landlord groups against renters, including threatening them with eviction.

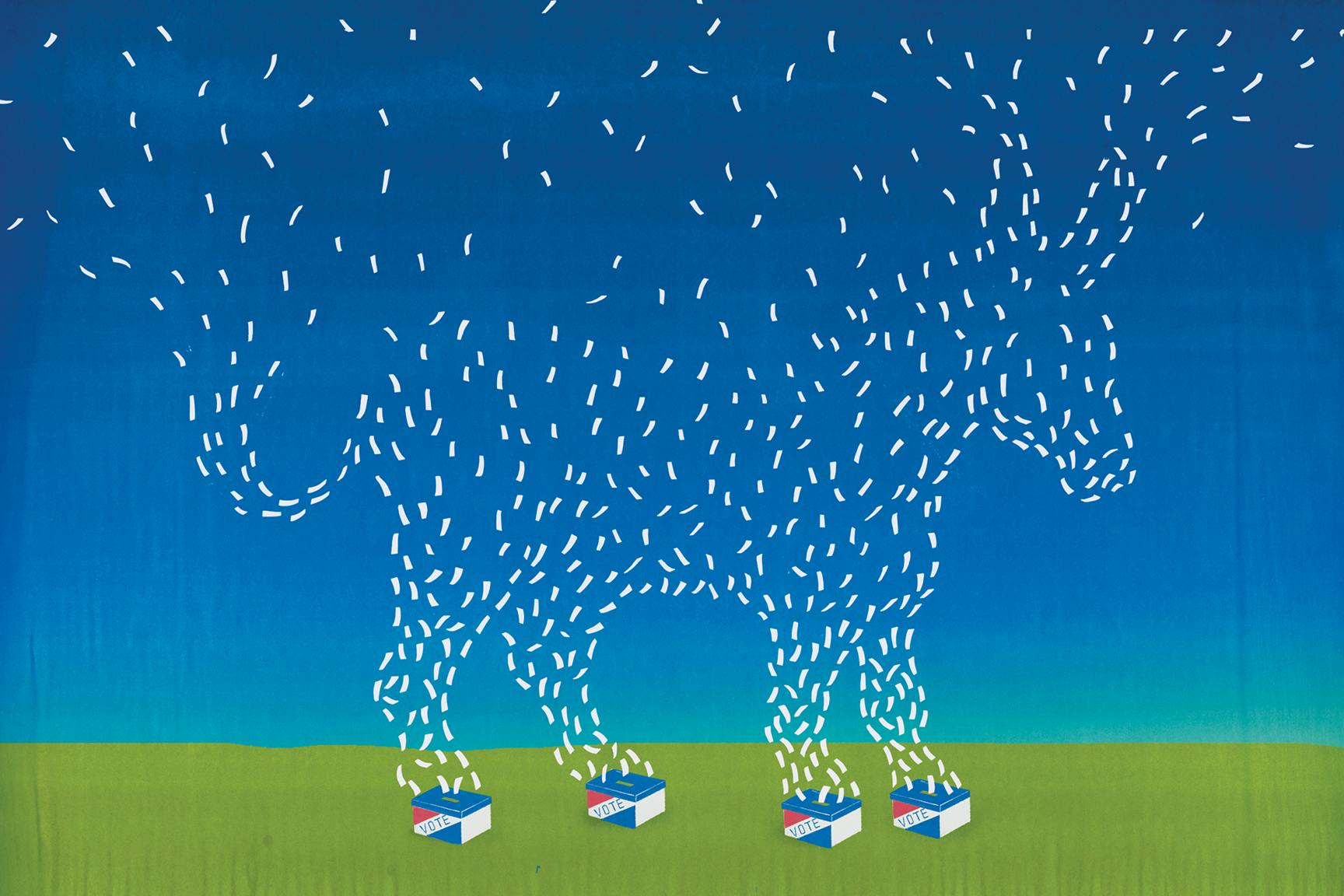

On a mixed Election Night for progressives, the fight for rent control in California hit a roadblock when Proposition 10 lost by more than 20 percentage points. Prop 10 would have repealed the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a state law prohibiting cities from enacting rent control on buildings constructed after 1995 (or earlier in some cities).

To those who have been watching the fight for Prop 10, the defeat came as little surprise. “The corporate landlord industry ran a campaign of lies and deception and put $80 million behind it,” said Amy Schur of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE), one of the organizations that led the “Yes” campaign on Prop 10. “A majority of voters in California support rent control but the opposition managed to sow tremendous confusion.”

As I reported in a previous piece for The New Republic, the opposition campaign was bankrolled directly by the biggest real estate groups in the country. By the end, these groups and their supporters doled out over $76 million, outspending the “Yes” campaign three to one. The landlord lobby’s massive ad campaign was accompanied, in the final weeks, by direct voter manipulation: Renters across the state received notification of rent hikes or eviction from landlords who explicitly cited Prop 10 as the reason, with some promising to drop the threats if the measure failed.

Big spending has long governed the ballot measure process in California. In 2005, a proposition to provide drug discounts to low-income Californians was defeated after pharmaceutical companies spent more than $118 million on opposition. The next year, a proposition to reduce petroleum consumption was defeated after energy producers funneled over $94 million into campaign efforts. Big money appears particularly dexterous at confusing voters facing ballot measures because those measures can be confusing to begin with—often designed to set the stage for future policymaking rather than to enact clear or immediate change.

The effect of the Prop 10 money was glaring: While only 38 percent of voters cast their votes in favor of Prop 10, a 2017 poll by the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, found that 60 percent of likely voters in the state support rent control. “I can’t tell you how many times I heard people say, ‘You vote no on 10 if you like rent control right?’” said Shanti Singh of the California renters’ rights organization Tenants Together. Tony Samara of Urban Habitat, a grassroots advocacy organization for low-income communities of color in the Bay Area, said that, due to the real estate lobby’s deception, there isn’t “any way you can say that Prop 10 was a referendum on rent control.”

The election wasn’t a total loss for affordable housing in California: Proposition 1, which will dedicate $4 billion in state bonds towards existing affordable housing programs, including the construction of new units for low-income residents, veterans, and farmworkers, secured a definitive win. Proposition 2 also passed, funneling $2 billion in state revenue into homelessness prevention housing. While the fight over Prop 10 was intense, these two passed with little effort: Just over $4 million was spent to support them in the face of negligible opposition. According to Peter Cohen, co-director of San Francisco’s Council of Community Housing Organizations, campaigning for Props 1 and 2 in San Francisco“was like handing out candy. They are such low-hanging fruit you don’t even really need to talk about them.”

Indeed, Props 1 and 2 drew support from across the political spectrum. While landlord groups were busy pummeling Prop 10 with one hand, they supported the bond measures with the other. According to campaign filings, Essex Property Trust, one of the biggest funders of No On Prop 10, gave $150,000 to the two propositions. Another rent control assailant, Equity Residential, gave $75,000. Measures to support affordable housing bonds also passed overwhelmingly in Austin, Portland, and Charlotte, all with support from real estate groups, which benefit from the influx of new property: These bonds dip into state funds rather than relying on new taxes or regulations.

Affordable housing advocates agree that the bond measures are a necessary and positive step, but say that they’ll only go so far, since they largely serve to increase housing supply without protecting existing residents or long-term affordability. “Everybody’s so into this whole supply, supply, supply argument,” said Cohen. “We need it all, from more money for brick and mortar to protections for tenants.” And construction is too slow to make up for decades of insufficient building. Out of the 1,388 units planned for construction with $310 million from a housing bond passed by the City of San Francisco in 2015, only 33 units have been constructed so far, and many of the units are only 10-15 percent to completion.

In other words, if real estate groups continue to dictate solutions to an affordable housing crisis in cities across the country, there is little hope of solving it anytime soon. Tenant protections like Prop 10 “drive right at the heart of the failure of the for-profit market,” said Samara of Urban Habitat. “[Prop 10] is a direct intervention into that failure.”

Housing advocates say the very terms of the debate have to change, away from the industry’s emphasis on keeping the housing market free from onerous regulation. “There’s an idea that there’s this ‘unregulated housing market,’” explained Shamus Roller of the National Housing Law Project. “But this isn’t the housing market that Adam Smith imagined. We have zoning codes and building codes—it’s one of the most regulated in the country, and right now most of those regulations benefit people who already own homes and have wealth.”

Changing the conversation in this way is a big lift, and all the more so because it falls entirely on the shoulders of those at the state and local levels. Tenant protections have long been sidelined at the national level, even by the strongest affordable housing advocates. For example, Senator Elizabeth Warren’s housing plan, the most progressive housing plan proposed in the Senate in decades, makes no mention of rent control, instead focusing on subsidizing new affordable units.

Despite this, California voters know the market isn’t working for them: More than 54 percent of renters in the state spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. A USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times survey before the election found that just 13 percent of eligible California voters believe that too little home building is a primary contributor to the state’s affordability issues. Lack of rent control was at the top of the list, with 28 percent.

And that number would likely be higher in a follow-up survey, particularly now that a spotlight has been put on the manipulative role played by real estate groups in the referendum. In October, two weeks before the election, The Guardian reported that Blackstone was using money from real estate investments funded by California public employees and the state university system to pay for its Prop 10 opposition campaign. “This campaign has helped expose the growing role of Wall Street in our housing in California and the role of groups like Blackstone that had been under the radar,” said Schur of ACCE. “The housing justice movement has grown by leaps and bounds through this campaign.”

And even as the flaws of the ballot measure process were exposed, its history also offers a source of hope: Many significant measures passed through the ballot were defeated on their first try. An initiative to soften and repeal some parts of the state’s infamous three strikes law narrowly lost in 2004 but passed in 2012. Marijuana legalization was defeated in 2010 but passed in 2016. The first time it appeared on the ballot, according to Mark Baldassare, CEO of the Public Policy Institute of California, people were hearing “mixed messages” on marijuana legalization. “But the next time around, there were less questions about it, more trusted sources of support, and public opinion had shifted because of what was going on in other states,” he said. Marijuana legalization ultimately passed by nearly 15 percentage points.

As the housing crisis intensifies, and as the call for rent control spreads, a 2020 ballot might turn up different results. But rent control advocates aren’t waiting for 2020. They’re launching local fights in cities across the state. “Until three years ago, it was unheard of to put rent control on local ballots,” said Singh. In Oakland on Tuesday, voters approved a measure to close eviction loopholes, and in Alameda, voters defeated a real-estate industry measure to preempt local rent control efforts. Sacramento has already confirmed a spot on the 2020 ballot for a rent control measure. Singh says that these local measures are crucial for the success of the statewide movement: “When you pass local measures, you build crucial infrastructure, like tenants’ unions who know their rights.”

Perhaps equally important, passing local measures builds knowledge among tenants of the rights they don’t have. Under Costa-Hawkins, any rent-controlled units will be subject to “vacancy decontrol,” which permits landlords to raise rents on an apartment after the previous tenants leave. “When you pass more local rent control ordinances, more people are going to run into the brutal reality of Costa-Hawkins,” explained Singh.

Local rent control efforts are also mounting pressure on state officials, like Governor-elect Gavin Newsom, to push rent control through by more expedient means than a ballot initiative. When tenant advocates urged the state assembly to consider repealing Costa Hawkins this past January, it failed to get the votes necessary to move out of committee. But today, Schur said, there are dozens of elected officials who have come out in support of it.

And, in the weeks leading up to the election, Newsom pledged, despite his opposition to Prop 10, to “take responsibility to address the issue.” The meaning of this pledge remains ambiguous, and a bill passed through the Assembly might be weaker than Prop 10, but the pressure to take action is undeniable. “We forced decision-makers to take sides,” said Schur. “Are you standing with the 17 million renters of California or are you standing with big landlords?”

On Wednesday, President Donald Trump spent his first press conference after a midterm rebuke ranting about the media. He said CNN should be “ashamed of itself” for its coverage of his administration and that reporter Jim Acosta was “a rude, terrible person.” He shouted at reporter April Ryan and told her to “sit down.” He blamed losses in the House of Representatives on Republicans who didn’t “embrace” him, like Utah’s Mia Love, but refused to accept any responsibility for the dozens of House seats that were lost. Then, a few hours later, he fired Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

Mitt Romney, meanwhile, was singing. Literally.

This campaign has been quite the ride. Thank you, Utah. pic.twitter.com/2vTxInB7by

— Mitt Romney (@MittRomney) November 7, 2018Driving down the highway, singing a Johnny Cash song, seemingly without a care in the world: Romney was having a pretty good day. He had just easily won election to the U.S. Senate, replacing Orrin Hatch. After spending much of 2016 sparring with Trump—including a blistering speech in which Romney declared him unfit for office—the two had seemingly come to a truce. During the campaign, Romney largely steered clear of Trump, and Trump largely steered clear of Romney.

No doubt, the newly minted junior senator from Utah would like to continue this dynamic. But that is unlikely to happen. As a representative of a red state that is more skeptical of Trump than most, and the biggest political star to enter the Senate since Hillary Clinton in 2000, Romney will be pressed repeatedly to comment on the Trump tweets, rants, and policy improvisations of the day.

The question facing Romney as he heads to Washington isn’t just how he’ll get along with Trump, but what his relationship with the president will say about who he is as a politician. With the exception of his 2016 speech against Trump, Romney has hardly been a model of political courage. But with the Senate losing its leading Republican critics of Trump—Bob Corker and Jeff Flake—there will be enormous pressure for him to take up their mantle.

Speaking on March 3, 2016, shortly after Donald Trump had become the presumptive Republican nominee for president, Romney held a press conference. “Let me put it very plainly,” Romney said. “If we Republicans choose Donald Trump as our nominee, the prospects for a safe and prosperous future are greatly diminished.”

Romney’s speech carried two distinct attacks. The first was that Trump was incapable of governing the country. Trump “has neither the temperament nor the judgment to be president,” Romney said, describing Trump as a bully, liar, cheater, and philanderer. These failures of character, as Romney told it, were connected to the campaign’s policy failures and showed his unseriousness as a presidential candidate. Trump’s bankrupt character, Romney argued, would cause crises in American foreign and domestic policy alike.

The second line of attack was that Trump was not a real Republican. “I believe with all my heart and soul that we face another time for choosing, one that will have profound consequences for the Republican Party, and more importantly, for our country,” he said near the beginning of the speech. He said Trump’s economic plans would create a “prolonged recession,” and his proposed tariffs “would instigate a trade war and that would raise prices for consumers, kill our export jobs and lead entrepreneurs and businesses of all stripes to flee America. His tax plan, in combination with his refusal to reform entitlements and honestly address spending, would balloon the deficit and the national debt.”

This was always an underappreciated element of Romney’s critique of Trump: that he was not sufficiently conservative. Note that one of Romney’s principle concerns was Trump’s pledge to honor Medicare and Social Security—a pledge that almost certainly helped propel him to victory—which he believes would “balloon the deficit.” Romney was undoubtedly worried about Trump’s character, but he was also concerned about the damage his candidacy was doing to the kind of doctrinaire conservatism that Romney espoused.

These are remarkably similar, if more pointed, arguments to the ones that Jeff Flake has made again and again over the past two years, particularly in Conscience of a Conservative. In that book, Flake argued that Republicans struck a “Faustian bargain” with Trump that would come to haunt them by undoing everything that the conservative movement, from Barry Goldwater to Ronald Reagan, stood for. Flake sees Trump as an Orwellian figure, a pathologically untruthful authoritarian who is undoing everything that America, and especially conservative America, stands for.

After Trump won the presidency, he appeared to dangle the job of secretary of state before Romney. Perhaps eager to join “The Committee to Save America,” Romney changed his tune. The charade resulted in a private dinner at the end of November and one humiliating photograph, which has since become a meme.

*record scratch*

*freeze frame*

Yup, that's me. You're probably wondering how I ended up in this situation ... pic.twitter.com/VC9XZblMGY

Trump never offered him the job, and likely just wanted him to grovel. Later, Trump confidante Roger Stone bragged that the president-elect was interviewing Romney “in order to torture him.”

If there was bad blood, Romney let it slide. During his run for Senate, he largely stayed out of national politics, coasting to victory on the back of endorsements from Hatch, the senator he was replacing, and Trump himself. Romney won the Republican primary with 71 percent of the vote, and cruised to victory on Tuesday with 59 percent.

But now that Romney is finally headed to Washington, after hoping to arrive there six years ago as president-elect, his days of flying under the radar are over. His every tweet and utterance will be scrutinized like never before, and he seems to recognize this already. He was among a handful of Republicans who spoke out about the future of the Mueller probe after Attorney General Jeff Sessions was forced to resign on Wednesday.

I want to thank Jeff Sessions for his service to our country as Attorney General. Under Acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker, it is imperative that the important work of the Justice Department continues, and that the Mueller investigation proceeds to its conclusion unimpeded.

— Mitt Romney (@MittRomney) November 7, 2018Fittingly, so did Jeff Flake:

Earlier this year, we passed S.2644, the Special Counsel Independence and Integrity Act, out of the Senate Judiciary Committee. The bill would safeguard Robert Mueller’s investigation. Leader McConnell should bring the bill to the Senate floor as soon as possible

— Jeff Flake (@JeffFlake) November 7, 2018They were joined by senators Susan Collins and Lamar Alexander. A week earlier, Flake and Romney also both made headlines by condemning Trump’s labeling of the media as the “enemy of the people.”

Romney will find himself in a similar position as Flake, who announced his retirement from the Senate last year. Like Flake, he will be made uncomfortable by the president’s demagoguery, and will likely feel the need to speak out against it. Facing little competition, he may become—or at least be seen as—the moral compass and conscience of Republicans in Congress.

Romney will also likely cast himself as the protector of an older strain of conservatism, and that will ultimately limit his efficacy, just as it did to Flake. As president, Trump has calmed conservatives’ fears by embracing policies that Paul Ryan and Mitt Romney have advocated for years—tax cuts, de-regulation, far-right judges, and, yes, entitlement reform. Flake voted with Trump regularly, and Romney surely will, too.

The objections to Trump, then, will be largely aesthetic—with a few exceptions. Like Flake, Romney is a free-trader who loathes tariffs. Flake threatened to stop confirming judges if Trump didn’t back down from his trade war. That would be an interesting threat from Romney, but he has much less leverage, given Republican gains in the Senate, expanding a slim 51-49 majority by several seats. On immigration, however, Romney is to the right of Flake—and even claims to be to the right of Trump on the issue, saying he will likely fall in line behind Trump’s militaristic immigration policy.

It’s possible that Romney will be Flake 2.0—not only criticizing Trump, but backing up his talk with action. It’s also possible he’ll become the next Lindsey Graham, a Never Trump senator who has become one of the presidents biggest boosters. That both paths are imaginable says a lot about Romney. He has always been a shapeshifter, proudly veering between New England Republicanism and extreme conservatism, depending on the political winds of the time. Most likely, he will try to thread the needle, calling out Trump when his GOP colleagues won’t, but supporting Trump’s most consequential policies. He may even become the face of Trumpism without Trump.

Ten years ago, environmental disaster struck Kingston, Tennessee. A dike containing massive amounts of coal waste burst, releasing 1.1 billion gallons of the heavy-metal sludge onto land and into waterways. It was the largest spill of coal ash slurry—a mixture of coal-burning byproduct and water—in United States history. The cleanup at the Kingston Fossil Plant took seven years.

Today, 30 of the laborers involved in the cleanup are dead. More than 250 are still sick. This isn’t a coincidence, they argue. The contractor they all worked for, Jacobs Engineering, “lied about the toxicity of coal ash, refused to provide them protective gear, threatened to fire them if they brought their own, [and] manipulated toxicity test results,” according to the workers’ lawsuit against the company.

On Wednesday, a federal jury ruled in the workers’ favor, finding that Jacobs Engineering “failed to ‘exercise reasonable care’ in keeping workers safe and, in its failures, likely caused the poisoning by coal ash of the laborers,” the Knoxville News-Sentinel reported. The verdict means the plaintiffs can seek monetary damages to cover medical testing and treatment of everyone who worked on the cleanup.

This is an important victory for those laborers and their families, albeit too late for some of them. But it also should serve as a warning to all Americans. The Trump administration is in the process of weakening the very regulations on coal ash that were put in place as a response to the spill in East Tennessee.

When power plants burn coal for energy, it creates coal ash. The waste typically contains a variety of heavy metals, anything from arsenic to selenium to chromium, depending on where the coal was mined. Exposure is therefore considered harmful to human health. Of the 110 million tons of coal ash produced in the U.S. every year, about half is recycled into construction materials. The rest is generally combined with water that’s stored in aging dikes and ponds.

The Obama administration proposed the first-ever federal regulations on coal ash in 2014. Finalized in 2015, the rule required all utilities to implement plans to control “fugitive” dust, the type of airborne coal ash that the Kingston cleanup workers were exposed to. It also imposed new safety requirements on new coal ash storage ponds and required some old ponds to close.

Under Trump, the Environmental Protection Agency has loosened those regulations. In July, shortly after Andrew Wheeler became the EPA’s acting administrator, the agency finalized rulemaking that “will allow coal ash impoundments that are at risk for leaks—including ones within five feet of groundwater or in wetlands or seismic zones—to continue operating beyond April 2019, when they were slated to close,” The Washington Post reported. “Instead, they may remain open under the new rule until October 2020.” The new rule will also “empower states to suspend groundwater monitoring in certain cases and allow state officials to certify whether utilities’ facilities meet adequate standards,” the Post wrote.

The EPA is also crafting another rule to prescribe how coal ash can be recycled and reused for construction material. Like most EPA observers, Earthjustice attorney Lisa Evans expects that restrictions on the practice will be loosened. She hopes, however, that the coal ash cleanup workers’ case might give the agency some pause. Recycling coal ash for construction material is “exactly the type of project that can create dangerous dust,” she said.

Wheeler being a former coal lobbyist, and Trump being Trump, it’s highly unlikely that the EPA will have a sudden change of heart when it comes to regulating coal ash. But Evans said she hopes the Kingston case raises public awareness of the dangers of loose regulations. Negligence may have caused the workers’ exposure, but an old storage pond caused the spill in the first place. “It’s not realistic to protect people one lawsuit at a time,” she said. “Lawsuits mean harm has already been caused. We want to make sure requirements are in place to prevent harm in the future.”

On Saturday, November 3, three days before the midterms, 200 volunteers gathered in Modena, New York, to canvass for Antonio Delgado, an African American lawyer and first-time congressional candidate. A local field staffer, a cheery young man named Todd, told me that so many people had shown up around the district to help Delgado unseat incumbent Republican John Faso that the campaign was able to knock on 65,000 doors that day, nearly the same number of votes cast in the district during the last midterm election. The next day, Delgado’s supporters hit another 50,000—a small part of a massive surge in organizing that took place across the country.

On Tuesday, Delgado was elected in a Democratic wave that (nearly) achieved the scale the party had hoped for. The wave crested in formerly Republican-leaning House districts all over the country, lifting first-time candidates like Abigail Spanberger in Virginia, Mikie Sherrill in New Jersey, and Kendra Horn in Oklahoma, and ultimately delivering the House to Democrats for the first time since 2010. It wrested seven governorships from Republicans, and while the wave wasn’t big enough to lift Andrew Gillum in Florida or Beto O’Rourke in Texas, they demonstrated unexpected strength in their campaigns.

There will be many explanations for these victories, but the sheer size of the volunteerism was clearly a deciding factor. The mobilization was not merely unprecedented for a midterm; it reached levels typically seen only in a presidential year. More important, activists developed new and different approaches to mobilizing the volunteers who were phone banking and knocking on doors this fall. Traditionally, most electoral organizing has been run through campaign committees that command powerful lists of millions of activists, donors, and volunteers. (Barack Obama, for example, had 13 million names, 3.95 million donors, and 35,000 volunteer groups on his 2008 list.) That model was already breaking down in 2016, with outside groups like Color of Change, Feel the Bern, and 350.org operating independently of the Democratic establishment. Two years later, however, liberal organizing has now spread out to dozens of independent national groups and thousands of local ones, most of them completely new and not directly connected to the party.

It didn’t have to be this way. Barack Obama’s field operation in 2008 was the best in a generation, but at its root, it was still conventional, an army commanded by field generals who closely managed its actions. Although the arrangement gave the Obama campaign highly effective control, it meant that when he was elected, his former campaign manager, David Plouffe, could mothball the entire apparatus, folding Organizing for America, and its 13-million-member email list, into the Democratic National Committee as a fully controlled subsidiary—a choice that sapped grassroots energy from the Democratic Party and contributed to its losing 968 state legislative seats over the next eight years.

After the disaster of Trump’s election, there was no organizing structure in place to come rescue the party. Into that vacuum came a new cohort of activists. To begin with, older women and younger but more experienced Democratic campaign staffers launched Indivisible. From a Google Doc started by a group of young congressional aides, it spawned 6,000 local chapters (at least two in every congressional district). The Women’s March prompted the launch of thousands of local huddles. And soon, a long list of new groups emerged to direct campaign knowledge, data, and resources wherever they were most needed.

The most notable aspect of Democratic midterm organizing in 2018 was that it operated without any central command. It was more like a swarm than an army, surging to places that traditional Democratic consultants never bothered to go. In Texas, Beto O’Rourke’s Senate campaign, which nearly brought the first statewide win to a Democrat there since 1990, hired people like Bernie Sanders’s deputy digital director, Zack Malitz, and built a large paid staff of 800, focusing on one main goal: a massive, decentralized base of volunteers. At the end of October, the O’Rourke campaign reported that its supporters had made 19 million phone calls to Texas voters, and sent more than one million texts each day. Nationally, Democrats were sending so many texts that Ann Lewis, MoveOn’s chief technology officer, has said that countrywide cellular networks were overloaded. On the weekend before Election Day, MiniVAN, an app Democratic canvassers use to keep track of their interactions with voters, was trending on the Apple store’s top ten list.

The fundraising landscape has also become more decentralized, even as billionaire megadonors like former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Tom Steyer spent heavily on the election. ActBlue—a Democratic online fundraising platform that allows people to send small donations to a wide range of candidates or causes, not just ones prioritized by the national leadership—processed a record 7.7 million donations between July and September, and the $385 million raised on the platform was almost five times the amount collected during the same period in the last midterms. Data for Progress—a small think tank co-founded recently by Sean McElwee, a New York journalist best known for coining the “Abolish ICE” slogan—worked with Run for Something and FutureNowUSA (two other new groups) to create “Give Smart” lists of strategic state legislative races where Democrats might be able to pick key seats to tip control of a chamber. Over a few days in October, following a few tweets from @DataProgress, some $750,000 flowed to the accounts of candidates who had previously been operating on small budgets.

Volunteers poured in, too. On the day before the election, Mobilize America, a new clearinghouse for volunteer organizing that was used by nearly 500 campaigns this cycle, reported that 370,000 volunteers had used its platform to sign up for 737,000 shifts over the course of the cycle, nearly half to canvass. (The real level of engagement was likely considerably higher, as many people brought a friend or took on an extra shift.) All told, according to organizations like Movement Voter Project, which raised more than $12 million for over 350 local groups, and Action Together Network, which connects more than 800 leaders across every state, the number of volunteers mobilized over the last 18 months exceeded two million people—nearly matching Obama’s 2.2 million in 2012. The left, in short, has rebuilt the muscle he let crumble after his first campaign.

That most of these new groups stand outside the main party structures is significant. No politician or campaign operative can control or dismantle them. That, in and of itself, is a major development, especially for the left, which has struggled to get a foothold within the Democratic establishment. Two years ago, most of these groups didn’t even exist. And yet this cycle, they were able to mobilize millions of previously disengaged voters and train thousands mostly on their own steam. That can only bode well for 2020. It’s possible, of course, that some of the energy of the new groups will fade after the midterms. But having experienced a degree of success, these organizers are unlikely to disappear entirely, and will keep pulling the Democrats forward in ways that can’t yet be predicted.

No comments :

Post a Comment