The Supreme Court appeared hesitant on Thursday to overturn almost two centuries of precedents that allow state and federal prosecutors to each charge a defendant for the same crime. In Gamble v. United States, one of the most closely watched cases of the term, the justices debated whether they and their predecessors have misread the Fifth Amendment’s double jeopardy clause for roughly 170 years—and, if so, whether they should correct that error now.

The clause forbids the government from prosecuting someone more than once for the same crime. There’s an exception, however, known as the separate-sovereigns doctrine, that allows multiple prosecutions if the defendant is charged by different legal sovereigns. A state can’t prosecute someone for the same offense twice. The federal government also can’t prosecute someone for the same offense twice. But a state and the federal government could each prosecute someone once for the same underlying conduct.

Justices Clarence Thomas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg have raised concerns about this doctrine in past decisions, so it’s no surprise that Thursday’s oral arguments scrambled the court’s usual ideological divisions. Ginsburg and Justice Neil Gorsuch took a more sympathetic view toward the defendants’ arguments against the doctrine, while Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Elena Kagan appeared skeptical that the court should overturn a legal doctrine so thoroughly entrenched in American criminal law.

The justices are generally reluctant to overturn the court’s previous rulings unless absolutely necessary, a legal doctrine known as stare decisis. “The bar that you have to clear, I believe, is not just to show that it’s wrong but to show that it’s grievously wrong, egregiously wrong, something meaning a very high bar, because stare decisis is itself a constitutional principle,” Kavanaugh asked Louis Chaiten, who argued for the defendant. “Can you clear that bar?”

The defendant, Terrence Gamble, was pulled over by Alabama police for a broken taillight in 2015. After officers found marijuana and a handgun while searching his car, local prosecutors charged him with possession of drugs and possession of a handgun despite a previous felony conviction. Gamble pleaded guilty to both charges. Shortly thereafter, federal prosecutors charged him with violating a federal law that prohibits people with felony convictions from owning a firearm.

Gamble argues that he is essentially being prosecuted twice for the same crime, and asked lower courts to quash the federal charges. They uniformly declined, citing the Supreme Court’s lengthy history of rulings in favor of the doctrine. Gamble contends that those rulings are based in a wrongful reading of the double jeopardy clause, which flatly forbids multiple prosecutions “for the same offense.” He also argues that the court’s current interpretation deviates from historical English and American practices at the founding. “The separate-sovereigns exception originated in ill-considered dicta and solidified through a series of decisions that ignored prior precedents and never meaningfully engaged with the text or original meaning of the Double Jeopardy Clause,” he wrote in his brief for the court.

The federal government strongly disagrees. In its court filings, the Justice Department cautioned the justices against changing a basic assumption upon which the nation’s criminal justice system is built. “For nearly 170 years, repeatedly and without exception, this Court has relied on the plain meaning of ‘offence’ and principles of federalism to recognize that state and federal offenses are not the ‘same,’” the government said in its brief for the court. “And both before and after incorporating the Double Jeopardy Clause against the States, the Court has rejected invitations—which raised arguments nearly identical to petitioner’s—to redefine the Clause.”

State attorneys general from 36 states—ranging from California and New York to Florida and Texas—also sounded the alarm. The states warned that overturning the doctrine would threaten the nation’s federal structure, the states’ fundamental sovereignty, and the interests of justice, especially by weakening federal civil rights laws. They pointed to the Rodney King beating in the early 1990s, where federal prosecutors charged the four Los Angeles police officers with civil rights violations after a local jury controversially acquitted them in a state trial.

Overturning the doctrine could also complicate prosecutions for crimes committed on tribal lands. Tribal governments enjoy the sovereign power to prosecute crimes committed within their borders. That power is limited, however, by Supreme Court precedents and by federal laws that give the Justice Department jurisdiction when major crimes are committed or non-Native American perpetrators are involved. The result is a thicket of laws, precedents, and practices that determine when a federal or tribal government will bring charges.

In a friend-of-the-court brief, the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center and the National Congress of American Indians warned the court that abandoning the doctrine could have dire implications for criminal cases on tribal lands, especially as they wrestle with an epidemic of domestic violence and sexual assaults. If a tribal government brings charges, the defendant may ultimately receive a much more lenient sentence than they would under federal law, they told the court. “And if a tribal nation elects to forego prosecution, in the hopes that the U.S. Attorney will conclude his or her investigation and bring federal charges, the victim may face a situation where no charges are brought at all—as federal prosecution is never guaranteed.”

The justices spent most of Thursday’s oral arguments diving into the pre-twentieth century precedents on double jeopardy. But many of the justices’ questions also focused on how scrapping the doctrine would play out in real-world terms. “How does it work as a practical matter?” Roberts asked Chaiten. “Is it a race to the courthouse? I mean, if a prosecution bars a subsequent one, the state and federal government may have different perspectives, is it whoever can empanel a jury first is going to block the others?”

“So, first of all, the norm in the country is cooperation between federal and state authorities,” Chaiten replied. “Well, it sure wasn’t entirely true at the time of the civil rights actions in the ’60s and ’70s,” the chief justice noted. “It wasn’t true at the time of the fugitive slave law.” The government picked upon this point during its turn before the justices. “You could imagine state prosecutors in California, as a protest against federal marijuana laws, allowing anyone who’s caught with 50 kilograms of marijuana to walk in and plead to a misdemeanor to frustrate federal prosecutions,” Eric Feigin, who argued for the federal government, offered as a hypothetical.

Gorsuch, who appeared to favor Gamble’s arguments, pointed out that the practical concerns cut both ways. He noted that the “proliferation of federal law,” with “over 4,000 statutes now and several hundred thousand regulations,” could give the federal government the opportunity to retry far more state-level cases than when the doctrine was first contemplated. “Why shouldn’t that be a practical concern we ought to be more concerned about today?” he asked Feigin.

Most of the attention surrounding Gamble v. United States stems from another case: Special counsel Robert Mueller’s wide-ranging inquiry into Russian interference during the 2016 presidential election. Some legal experts have warned that jettisoning the separate-sovereigns doctrine could endanger Mueller’s ability to pressure witnesses to cooperate and make it easier for President Donald Trump to shut down the inquiry.

This fear isn’t completely unfounded. As Mueller’s investigation has drawn closer to the White House, Trump has ratcheted up his efforts to interfere in the inquiry. The president could theoretically fire Mueller, shut down the investigation, and issue pardons to anyone under the special counsel’s scrutiny. That last part is especially worrisome. Presidential pardons are definitive and irrevocable: They can’t be overturned by future presidents or by Congress, and the Supreme Court has long held that presidents have broad discretion in their usage.

Two limits exist on the president’s pardoning power under current law and precedents. It can’t be used to evade impeachment by Congress, and it only applies to federal criminal offenses, not state ones. That last provision amounts to something of a backstop for the Russia investigation if Trump makes a Nixonian push to shutter the Justice Department’s inquiry. Even if Trump pardons everyone involved, New York and Virginia could theoretically prosecute key witnesses instead. Mueller has stayed characteristically silent on whether this is part of his strategy, and state attorneys general have declined to comment publicly on the matter.

Not every legal expert sees Gamble as a potential threat to the Russia investigation. Fordham University law professor Jed Shugerman and appellate lawyer Teri Kanefield wrote in October that Mueller could structure the charges so that he didn’t prosecute anything that the state attorneys general could not. In the case of Paul Manafort, the jury’s failure to reach a verdict on ten charges during his trial in Virginia last August may have made this easier. “Those deadlocked charges left a mistrial that could theoretically be retried on the federal or state level without a double jeopardy problem, with or without Gamble,” they wrote. “When Manafort pleaded guilty [in September], Mueller seemed to leave the door open on many charges by state prosecutors.”

The justices and the lawyers arguing the case made no mention of Mueller, presidential pardons, or anything suggesting that the Russia investigation was foremost on their minds. Whether a decision in Gamble’s favor would affect it is one of many questions that can’t be fully answered. “The states and the federal government have never had to be concerned about who goes first,” Hawkins told the justices. “Under the law of unintended consequences, surely there are practical problems that would arise from [the defendant’s] position that we may not have even thought about today.” A decision is expected by June.

By this time next year, dozens of Democrats will have declared their candidacy for president; by this time next year, it’s possible that a dozen or more will already have dropped out. Party leaders are expecting “30+ candidates” in what Axios reports will be “the biggest strategic free-for-all in modern political history,” outpacing even the GOP’s 2016 clown car primary. Rumored candidates include lefty senior citizens Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, billionaire neophytes Tom Steyer and Howard Schultz, and rising stars (and recent campaign losers) Beto O’Rourke and Andrew Gillum.

But two Democrats who were considered potential frontrunners will not be among them. Over the last week, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick both announced that they will not seek the nomination. Their announcements came as something of a surprise, given that they’ve long been thought to have presidential aspirations and are experienced governors at a time when the Democratic field is thin on executive experience. Cuomo easily defeated a progressive challenger on his way to a third-term victory, and Patrick had a powerful ally in a potential candidacy: Barack Obama.

But Cuomo and Patrick likely realized that with the party’s shift to the left over the past few years, their path to the nomination was narrow. They’re both corporate-friendly Democrats without immediately apparent constituencies (outside of the donor class). Their absence, however, tells us a great deal about how the Democratic field is shaping up—specifically what the party establishment is looking for in a candidate.

A Cuomo presidential campaign, were it to materialize, would look a lot like his recent run for a third term as governor of New York. He cast himself as a Lyndon Johnson figure—a master dealmaker willing to get his hands dirty in pursuit of concrete accomplishments. “I am not a socialist. I am not 25 years old. I am not a newcomer,” Cuomo told reporters when asked if he worried about younger, left-wing Democrats like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “But I am a progressive, and I deliver progressive results.” Running against Cynthia Nixon in the Democratic primary, Cuomo touted legislation on gay marriage, gun control, and free college as proof that his brand of pragmatism works. His message was similar to Hillary Clinton’s approach during the 2016 primary, when she defended her own incremental approach to politics.

But Cuomo has also spent his time in office stifling progressives in his state, going as far as to prop up Republican control of the state senate so that a number of measures never made it to his desk. Cuomo has touted his business-friendly bona fides, culminating in his successful wooing of Amazon, while advocating for tax cuts and often seeming indifferent to social spending. He also has ethical baggage. Two of his top aides were convicted on corruption charges earlier this year. “For any other governor in America, this would be earth-shattering, but in Andrew Cuomo’s Albany, it was just a Thursday,” Nixon said after Cuomo’s economic guru was convicted on corruption charges in July, in a line that likely would have been repeated in a Democratic presidential primary.

If Cuomo’s progressive record as governor was debatable, Patrick’s was almost non-existent. He had a mixed, unremarkable record: He was instrumental in the defeat of a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage, but expanded charter schools and legalized casinos. His most ambitious plan, a $1.9 billion tax increase to fund a statewide rail expansion, went nowhere. And he accrued political baggage almost immediately after leaving office in 2015 by joining Bain Capital, the private equity firm whose role in outsourcing jobs helped cost former partner Mitt Romney the presidency in 2012. Still, Patrick is popular among former Obama administration officials. “If you were to poll 100 notable Obama alumni, the only two people who would win that 2020 straw poll right now are [Joe] Biden and Patrick,” a former White House aide told Politico last year.

Given the leftward drift of the party and the criticism Clinton and Obama received for cashing in on Wall Street speeches, it’s perhaps not surprising that Cuomo and Patrick decided to back out. In a crowded primary field, their records would immediately come under fire; indeed, they would likely be synonymous with the corruption of the party’s elite. The party’s donor class perhaps would have kept their campaigns aloft for a time, but ultimately Cuomo, very much the machine Democrat, and Patrick, who has been out of politics for three years, would not have an immediate base of support. Big-donor dollars can only get you so far, especially against candidates like Sanders and Warren who are proven small-donor powerhouses.

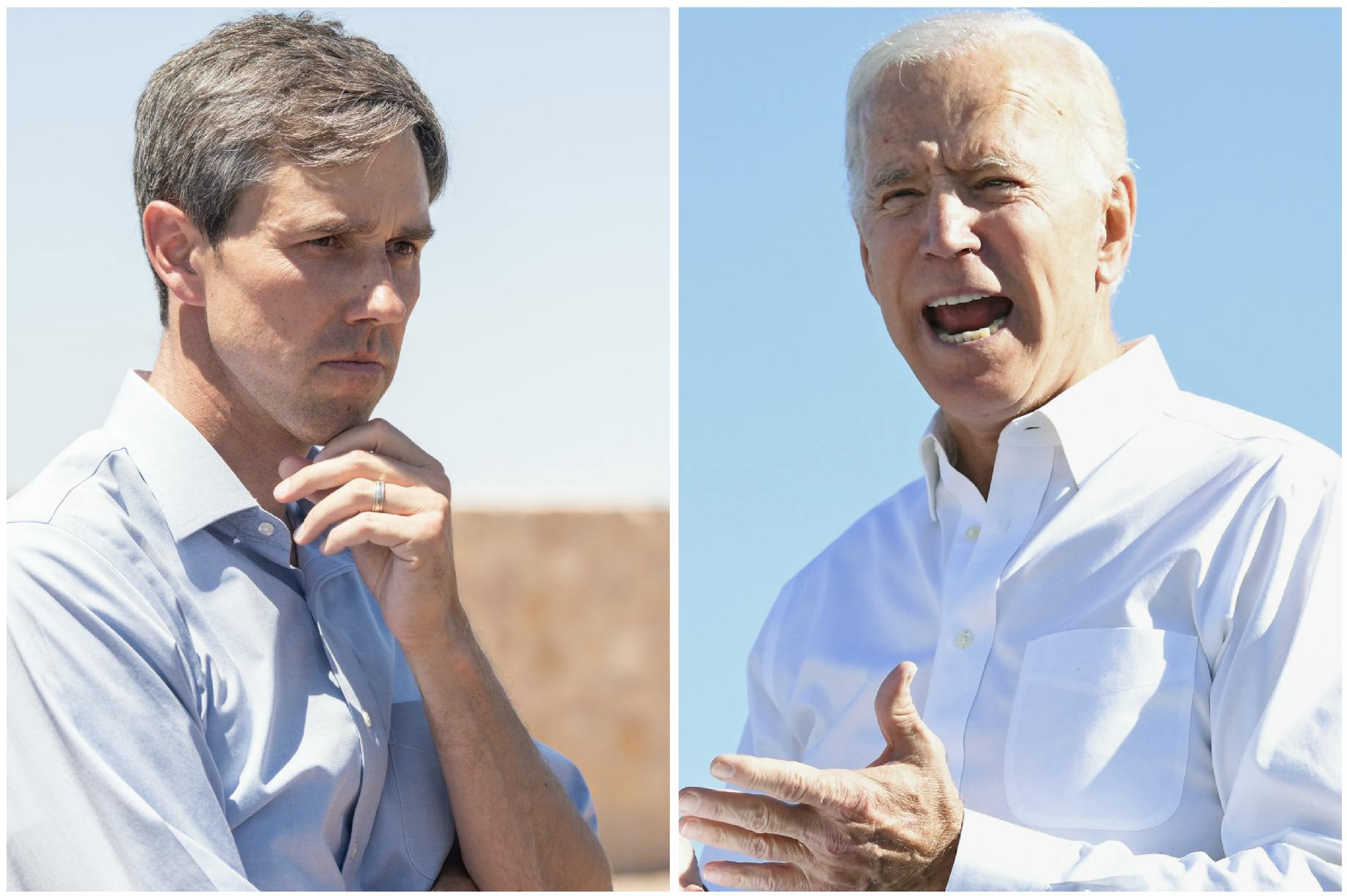

With Cuomo and Patrick bowing out, the Democratic establishment appears to be focusing its attention on Biden and O’Rourke. For months, Biden has been cited as a favorite of former Obama officials. While there’s a bumper crop of progressives, centrist Democrats have few options—and none with Biden’s name recognition. O’Rourke is hardly the insider that Biden is, but he has been wooed by Obama in recent days and was publicly urged to run by former Obama aide Dan Pfeiffer. Both potential candidates have in spades what Patrick and Cuomo lack: charisma and authenticity.

Both have flaws as well. Biden will be 78 in January of 2021, when he would assume office if elected, and has a long, checkered legislative record. “Among the potential trouble spots is a 2005 bankruptcy law he championed that made it harder for consumers and students to get protection under bankruptcy,” USA Today explained, “and the 1994 crime bill that created financial incentives for states that imprison people, affecting many black and Latino youths.” Biden also played a pivotal role in the shameful treatment of Anita Hill when she brought sexual harassment allegations against then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in 1991.

There is less to say about O’Rourke, a relatively inexperienced politician who has not distinguished himself in his three terms in the House. O’Rourke became a Democratic darling during his run against Cruz, but there are doubts about his progressive bona fides. While serving in the House, O’Rourke was a member of the centrist, corporate-friendly New Democrat caucus. Despite calling for universal health care on the campaign trail, he notably did not sponsor the House’s Medicare for All bill. On health care and the environment, O’Rourke’s statements have been mushy and thin.

Still, many in the party’s elite—particularly former Obama staffers—are looking toward Biden and O’Rourke as their best hope. Both O’Rourke and Biden could be counted on to pursue a more moderate course than many of the other leading candidates, particularly Sanders and Warren. But they also appear to command loyalty, with Biden still beloved from his vice presidential days and O’Rourke having become a national sensation during his run against Cruz.

“That ability to make people feel invested in [O’Rourke’s] campaign and his story does remind me of Obama ’08,” former Obama speechwriter David Litt told The Hill. “You see the crowds and the enthusiasm, the kind of movement that isn’t about me but about us ….” Another former Obama aide said, “The party hasn’t seen this kind of enthusiasm since Obama. There isn’t one other potential candidate out there that has people buzzing. And that’s exactly why people supported Obama and why they’ll support Beto.” O’Rourke, who pledged that he would not run for president while running for the Senate in Texas, recently said that he was open to 2020. Biden, meanwhile, is expected to make up his mind soon.

If one thing is clear, it’s that the party’s establishment isn’t much interested in policy—at least not yet. Instead, those urging Biden and O’Rourke to run are doing so with emotional appeals. The two men would be greeted with skepticism from the party’s left flank, but they’re seen as authentic in a way that almost none of the leading progressive contenders are, minus Sanders (and perhaps Warren). If the party’s elite gets behind one of them, they’ll be betting on personality more than policy.

At this point, the evidence that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman knew about—and likely ordered—the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi is compelling. After CIA Director Gina Haspel’s presentation to Congress earlier this week, Senator Bob Corker told reporters that a jury would find the prince guilty “in thirty minutes.” The only holdout is the president, who continues to stand by his statement that “we may never know all of the facts surrounding the murder of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi.” His support for Saudi leadership remains unwavering, even in the face of opposition from media, Congress, and his own intelligence agencies.

Indeed, between special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation’s increasing focus on Gulf money, and Trump’s repeated support for the Saudis and Emiratis in regional and international affairs, you’d be forgiven for thinking that perhaps it’s these states—not Russia—who have undue influence over the president. While there is no suggestion so far of quid pro quo between the president and his friends in the Gulf, the shady connections built during and after the 2016 election have combined with a broader network of money, personal ties, and some genuine policy agreements to produce what is perhaps the most pro-Saudi administration in U.S. history.

The United States has long pursued a generally pro-Saudi policy in the Middle East, a legacy of the Cold War when the United States relied heavily on the Saudis to push back against Soviet influence. Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical importance–and its position as the world’s swing producer of oil–has often led U.S. policymakers to minimize criticism of Saudi Arabia. Even as fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers were shown to be Saudi citizens, for example, the George W. Bush administration pushed to maintain the close U.S.-Saudi relationship while privately criticizing Saudi support for religious extremism. The Trump administration, however, has taken the United States’ selective vision on Saudi Arabia to new extremes.

In May 2018, The New York Times reported that the Mueller investigation into foreign influence in the 2016 election was looking at not just Russian, but possible Middle Eastern influence: Diplomats from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), it appeared, had facilitated meetings between Russian officials, mercenary-for-hire Erik Prince, and members of the Trump transition team. The lens quickly widened to include adviser to the Emirati government George Nader, a Lebanese-American businessman who helped to set up meetings at Trump Tower with an envoy for Saudi and Emirati leaders, and key officials including Steve Bannon and Jared Kushner.

In addition, the special counsel is apparently interested in Nader’s work on behalf of Saudi and Emirati leaders, funneling at least $2.5 million in Gulf money to Republican donor Elliott Broidy. Some of it appears to have been used for anti-Qatar lobbying following the blockade of that country in June 2017: A separate New York Times report in May 2018 pointed to two Washington, D.C., conferences featuring anti-Qatar views held by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and the Hudson Institute.

The special counsel is also investigating the emails of John Hannah, a senior counselor at FDD, former advisor to Dick Cheney, and Trump transition official for his ties to Nader and the Gulf States. During his time on the transition team, Hannah helped to arrange meeting—to discuss the potential for regime change in Iran—between Nader, disgraced former National Security Advisor Mike Flynn, and Saudi general Ahmad Asiri.

There is little suggestion of electoral collusion or quid pro quo (of the sort critics imagine with Russia) between the Gulf states and the Trump campaign. Though a meeting took place at which Nader informed Donald Trump Jr. that Mohammed bin Salman and Mohammed bin Zayed—de facto rulers of Saudi Arabia and the UAE respectively—were keen to see his father win the election, there’s no evidence any help materialized.

Still, there is a clear pattern of efforts to buy influence, often covertly. There is also a well-documented web of money linking the Saudis and Emiratis to the administration, its close backers, and the Trump family. Some of it is legitimate business activity. Over the decades, Trump has undoubtedly made millions from rich Gulf real-estate speculators. During the campaign, he even pointed it out publicly. “Saudi Arabia, I get along with all of them,” he bragged at a 2015 campaign rally. “They buy apartments from me. They spend $40 million, $50 million. Am I supposed to dislike them?”

The Gulf states have been among the biggest spenders at Trump hotels and resorts since he was electedThe Gulf states have been among the biggest spenders at Trump hotels and resorts since he was elected. In August of this year, the Trump hotel in New York finally reversed a two-year trend of falling revenues when Mohammed bin Salman’s extensive entourage paid premium prices for a last-minute stay. The Saudi government has also been among the biggest spenders at Trump’s Washington, D.C., hotel, spending $270,000 in 2016 alone.

Though the Trump Organization has promised that all profits received from foreign governments at these properties will be donated to the Treasury, ethics experts dispute the methods used for calculating these profits, suggesting that the president continues to profit from foreign spending. Several of Trump’s most influential backers–such as Broidy or the investor Tom Barrack—also profit handsomely from business ties and interests in the Gulf States.

The secrecy surrounding Trump’s financial affairs makes it difficult to know exactly how extensive these ties are. During the firestorm following Khashoggi’s death, Trump tweeted that he had no financial interests in Saudi Arabia. As various journalists noted, the statement could be technically true—in other words, no investments physically located within the country’s boundaries—while still misleading, given the Trump hotels’ many Saudi customers. And as always, Trump’s family members further complicate the picture. Over the last few years, for example, the Kushner family’s attempts to refinance or sell their disastrous New York real estate holdings included a failed attempt to secure funding from Qatar–a fact that’s hard not to see as relevant when evaluating Kushner’s unusual hostility toward Doha.

To be sure, money is not the only thing that ties the Trump administration so closely to the Gulf states. As with any administration, personality plays a role. The Saudis gave Trump the red-carpet treatment during his trip to Riyadh last year, a key element in winning over the mercurial president. Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, has reportedly built a friendship with Mohammed bin Salman.

Moreover, there is some genuine policy affinity between the two sides. From Michael Flynn to John Bolton, the Trump administration has been replete with the kind of Iran hawks that delight policymakers in the Gulf. Meanwhile, the administration’s notoriously pro-Israel and pro-Likud stance has been helpful as the Gulf states try to build a stronger regional partnership with Israel against Iran.

It remains to be seen whether Mueller’s investigation will untangle the web of money tying the Trump administration to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. But the network has clearly produced dividends: an administration that is almost reflexively supportive of every key Saudi foreign policy priority.

Take Iran, where Trump has withdrawn the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, reimposed sanctions and cracked down on U.S. allies in Europe and Asia. His decision to end the nuclear deal was opposed by other U.S. allies, China, Russia, most arms-control and regional specialists, and even his own secretary of defense and secretary of state; it was, however, supported by Saudi and Emirati leaders, who oppose Iran’s regional influence, and were willing to fill the gap by boosting their own production in response to sanctions on Iranian oil.

The president also idiosyncratically backed Saudi interests during the Gulf Cooperation Council crisis which broke out in 2017. As Saudi Arabia and the UAE blockaded Qatar, Trump tweeted his strong support. Again, administration officials like Defense Secretary James Mattis–likely mindful of the thousands of U.S. troops currently stationed inside Qatar–opposed the blockade, and sought to mediate an end to the crisis. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson even intervened to try to prevent a Saudi invasion of Qatar. Leaked emails later suggested that for his trouble, both the Emiratis and the Saudis used their influence with the president (and with Kushner) to have him fired.

The administration has displayed unwavering support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen, an ongoing humanitarian disaster. It continues to arm and aid the Saudi-led coalition, despite repeated reports of Saudi war crimes. Even the recent decision to end refueling support for the campaign came only after sustained congressional and public pressure, and the threat of a congressional rebuke on the topic. Indeed, the administration has actively worked with congressional leadership to shut down bills that would end U.S. support for the conflict.

Arms sales are another area where the Gulf States have benefited during the Trump administration. Though the president himself likes to portray such sales as vital to the United States economy, the actual financial and job-related benefits are small. Instead, these sales are hugely beneficial to the Saudi government, allowing them access advanced weapons and to replenish armament stocks. Recent reports suggest that Kushner even pushed to inflate the reported value of arms sales to the Kingdom in order to further bolster the partnership.

Perhaps the most striking indication of the administration’s excessive willingness to bend to Saudi interests is in its refusal to criticize the murder of Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist and U.S. resident killed in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. In any other administration, this action would have drawn clear condemnation and policy response. In the Trump era, the administration has displayed skepticism towards its own intelligence agencies, while maintaining its support for Saudi leaders.

To what extent were any of these decisions the direct result of money and influence from the Gulf States? It’s impossible to say. For starters, we may never know the extent of the financial ties between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Trump’s businesses, family, and donors. Though Mueller’s report may eventually clarify some of these questions, much of it lies outside the expected scope of the investigation. It’s unclear whether other lawsuits—such as one targeting Trump’s businesses as violating the emoluments clause of the constitution—will be successful in subpoenaing records on this question.

More importantly, though, it’s difficult to distinguish influence during the Trump administration from general attempts by these states to buy policymaking influence here in D.C. As a recent report from the Center for International Policy (CIP) illustrated, Saudi lobbying in Washington has grown exponentially in recent years, costing $27.3 million in 2017 alone. In addition to the money that goes to traditional lobbyists, Saudi funding goes to think tanks, universities, and other institutions which can influence U.S. foreign policy.

Despite rules on foreign election funding, at least some of that money even goes to politicians: The CIP report suggests that more than one-third of the congressmen contacted by lobbying firms like the Glover Park Group or DLA Piper on behalf of Saudi Arabia later received a campaign contribution from a registered foreign agent at the firm—in other words, a U.S. citizen, but one paid by a foreign government. As the report notes, “while it’s true that foreign nationals are prohibited from making contributions to political campaigns, there’s a simple work-around, one the Saudis obviously made use of big time … just hire a local lobbyist to do it for them.”

The presence of this foreign money sloshing around in Washington raises serious concerns for the independence of U.S. foreign policy. Even in the absence of a clear quid pro quo, the Trump family benefits financially from its ties to the Gulf states. Adam Schiff, incoming chair of the House Intelligence Committee, has promised to probe these ties, though it’s likely impossible to tell the extent to which money—rather than personal factors or policy agreement—is driving Trump’s foreign policy decisions.

No one, however, can deny that money plays a role. Even as Mueller finishes his work, therefore, one thing is already clear: It’s not just Russian meddling in U.S. foreign policy that we should be concerned about.

Best Buy has reportedly leaked two upcoming laptops from LG, the Gram 17 and the Gram 2-in-1, ahead of their official announcement.

Best Buy has reportedly leaked two upcoming laptops from LG, the Gram 17 and the Gram 2-in-1, ahead of their official announcement. The Acer ED242QR sports a 24-inch curved, VA panel that operates at a brisk 144 Hz.

The Acer ED242QR sports a 24-inch curved, VA panel that operates at a brisk 144 Hz.

No comments :

Post a Comment