In the classic comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, the titular characters occasionally play a game known as “Calvinball.” The rules are simple: Hobbes makes them up as he goes. In one strip, the imaginary stuffed tiger declares mid-game that Calvin has entered an “invisible sector” and must cover his eyes “because everything is invisible to you.” The six-year-old boy obeys and asks Hobbes how he gets out. “Someone bonks you with the Calvinball!” Hobbes exclaims, chucking the volleyball at Calvin. And so it goes until Calvin, in the final panel, is dizzy and disoriented. “This game,” he notes, “lends itself to certain abuses.”

American democracy is starting to feel the same way. In November’s midterm elections, voters across the country handed the Democratic Party 40 House seats, control of multiple state legislatures, and an assortment of governorships and other state offices. Now, one month later, GOP lawmakers in multiple states are using lame-duck sessions to hamstring incoming Democratic elected officials, either by reducing their official powers or transferring them to Republican-led legislatures.

Much has been written about Trumpism and the threat it poses to American democratic governance, and rightly so. But these state-level tactics aren’t new. Over the past decade, Republican lawmakers in North Carolina mastered the strategy of constitutional hardball to preserve their political muscle even as their electoral advantage shrank. The metastasis of this model today may be an even greater threat to the nation’s political health than Trump himself.

In the November elections in Michigan, after a long period of Republican rule, Democrats captured the governorship and the offices of the secretary of state and attorney general after a long period of Republican rule. Now, Republican legislators are weighing measures that would diminish the powers of the latter two positions. One proposal would give state lawmakers the legal standing to defend laws in court when the attorney general declines to do so. Another would transfer the secretary of state’s oversight over campaign-finance regulations to a new oversight board, whose members would be equally chosen by the governor and the legislature.

Wisconsin Republicans are considering even more aggressive steps after Governor Scott Walker lost to Democratic challenger Tony Evers last month. In a series of bills unveiled on Friday, GOP lawmakers aimed to seize a broad array of powers from Evers before he can take office. The Republicans want to empower state legislators to block the governor from changing regulations on healthcare and voting rights, denying Evers the ability to fulfill campaign pledges he was elected to carry out. They also want to reduce the governor’s influence over the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation, a state-run corporation that played a key role in the controversial Foxconn deal championed by Walker.

Other measures are aimed at the attorney general’s office, where Democrat Josh Kaul toppled Republican incumbent Brad Schimel. One proposal would allow the state legislature to hire its own lawyers to defend the constitutionality of laws without the attorney general’s participation. Another would abolish part of the attorney general’s office that handles appeals in federal courts, limiting the state’s ability to participate in multi-state lawsuits against the Trump administration.

Still other provisions are aimed at retooling the state’s elections. The bills would slash early voting in the state from six weeks to two weeks, a move that will likely suppress turnout among communities that tend to vote Democratic. It would also separate the 2020 presidential primary election from nonpartisan state races that same year. That appears to be aimed at giving Republicans a chance to elect a conservative Supreme Court justice in that year’s race and bolstering their control over that court.

Top Republicans in Wisconsin aren’t disguising the partisan aims of their legislation, which drew protesters to the state’s capitol building on Monday. “Most of these items are things that either we never really had to kind of address because, guess what? We trusted Scott Walker and the administration to be able to manage the back-and-forth with the legislature,” Scott Fitzgerald, the Wisconsin Senate’s majority leader, said in an interview with a conservative talk-radio host. “We don’t trust Tony Evers right now in a lot of these areas.”

This approach to governance was devastating enough in North Carolina. Its spread to other states is a grim sign for purple and red states. If Republicans are unwilling to be governed by another political party, one need not be a political scientist to understand how harmful that will be to democracy itself.

The Republican Party made extraordinary nationwide gains in the 2010 midterms in Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin, and other purple states. Their timing was particularly fortuitous: It gave the GOP control of key state legislatures and governorships immediately after the 2010 U.S. Census, which gave them the upper hand when drawing the state legislative maps and federal congressional districts that would stand for the next decade. Thanks to that advantage, Democrats had to pull off a wave election of their own in 2018 just to win a modest majority in the House of Representatives.

Gerrymandering is as old as the republic itself, and neither party’s hands are clean when it comes to drawing legislative districts for partisan advantage. What distinguished the post-2010 wave of Republican gerrymandering was its sheer aggressiveness. In Wisconsin, the GOP commands near-supermajorities in the state assembly and state senate despite drawing roughly even with Democrats in the statewide popular vote. North Carolina Democrats won nearly half of the statewide popular vote in congressional races but captured only three of the state’s House seats.

With a stranglehold on the legislature, North Carolina Republicans passed a slate of restrictive voting laws, including voter-ID measures, curbs on early voting, and new hurdles to cast absentee ballots. Though pitched as defenses against purported voter fraud, their practical impact is the suppression of votes in disadvantaged communities. A federal judge struck down North Carolina’s voter ID law as unconstitutional last year after concluding that it was designed to target black voters “with almost surgical precision.” Not all of these laws get blocked by the courts, however. Schimel, the ousted Republican attorney general in Wisconsin, partially attributed Trump’s victory there in 2016 to the state’s strict voter-ID law.

What happens if, despite Republicans’ best efforts and structural advantages, voters somehow manage to elect a Democratic candidate to statewide office? Then you simply strip as much power as you can from that office, within the state constitution’s boundaries. In 2016, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, trounced Republican Pat McCrory. State GOP lawmakers responded by passing a series of laws that reduced the number of appointments Cooper could make, including to the University of North Carolina system’s board of trustees, and also forced him to seek legislative approval for his cabinet picks. Cooper managed to claw back some powers after protracted legal battles, and voters rejected a legislature-backed initiative in November that would have stripped him of his judicial appointments as well.

Democracy, both as a system of government and as a way of life, needs more than just legislation and constitutions to function. It also requires a shared understanding of the bounds of acceptable political action. Without that shared understanding, the laboratories of democracy, as Justice Louis Brandeis once put it, become breeding grounds for oligarchical rule. “The only permanent rule in Calvinball,” Calvin exclaims in one strip, “is that you can’t play it the same way twice!” That may work with an imaginary friend, but it’s a dangerous way to run a country.

Nine months ago, President Donald Trump brushed off growing criticism of his escalating trade war with China and a host of traditional American allies. “When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with,” he tweeted, “trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

In recent days, after a “highly successful” working dinner with Chinese Premier Xi Jinping at the G-20 summit, Trump has all but declared victory in the trade war. On Saturday, he described the potential agreement as “one of the largest deals ever made,” and tweeted on Monday:

My meeting in Argentina with President Xi of China was an extraordinary one. Relations with China have taken a BIG leap forward! Very good things will happen. We are dealing from great strength, but China likewise has much to gain if and when a deal is completed. Level the field!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 3, 2018Farmers will be a a very BIG and FAST beneficiary of our deal with China. They intend to start purchasing agricultural product immediately. We make the finest and cleanest product in the World, and that is what China wants. Farmers, I LOVE YOU!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 3, 2018President Xi and I have a very strong and personal relationship. He and I are the only two people that can bring about massive and very positive change, on trade and far beyond, between our two great Nations. A solution for North Korea is a great thing for China and ALL!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 3, 2018Trump’s version of events differed substantially from the White House’s version, and from reality. As Vox’s Jen Kirby pointed out, the potential agreement is “more of a trade-war time out” than a resolution of the issues that led the United States and China to this point. Trump has simply offered to delay raising an additional $200 billion in tariffs; the two countries have 90 days to come to an agreement. In a cautious statement, the White House noted that China had agreed to purchase “a not yet agreed upon, but very substantial” amount of American products in order “to reduce the trade imbalance between our two countries.” This is probably good news for both countries and the suddenly sputtering global economy, but it’s nothing close to the success that Trump is claiming.

This fits a familiar pattern. Trump ratchets up hostilities with foreign governments in an attempt to negotiate (or renegotiate) deals that are more favorable to the U.S. But then he agrees only to superficial changes, which he nonetheless presents as historic wins that only he could accomplish. It’s a reminder that his real skill as a businessman—and now a politician—was never in making deals, but in marketing himself as a dealmaker. While that proved effective on the campaign trail in 2016, it may come back to haunt him in 2020.

Trump began his presidential campaign by touting his business experience as proof that he could improve trade deals. “Free trade can be wonderful if you have smart people [negotiating], but we have people that are stupid,” he said in his announcement speech in 2015. “When was the last time anybody saw us beating, let’s say, China in a trade deal? They kill us. I beat China all the time.”

While campaigning for president, Trump routinely cast himself as the world’s greatest negotiator—someone who would use the techniques that made him rich to benefit the country. “I have made billions of dollars in business making deals,” he said while accepting the Republican nomination for president in 2016. “Now I’m going to make our country rich again. I am going to turn our bad trade agreements into great ones.”

One of Trump’s first acts as president was an executive order withdrawing the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Then he went after NAFTA. He picked diplomatic and personal fights with the leaders of both Mexico and Canada, bickering with their respective leaders about immigration and trade, respectively. (Trump went as far as to refer to Canada’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau, as “weak” and “dishonest” at a G7 meeting in June.) But he also used tariffs, hitting Canada and Mexico on steel and aluminum in particular, in an effort to draw them to the table. “Without tariffs, we wouldn’t be talking about a deal,” he said after the new deal was announced in October. “Just for those babies out there that talk about tariffs—that includes Congress, ‘Please don’t charge tariffs’—without tariffs, we wouldn’t be standing here.”

But the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), announced in September, mostly just tweaks NAFTA. It doesn’t do much to alter its corporate-friendly framework or to help workers or consumers, as Trump promised a renegotiated NAFTA would do; instead, the deal largely benefits existing industrial titans at the expense of labor, with only auto workers receiving a raise (though car companies have already found a loophole to avoid raising wages).

“Overall, the changes from the old NAFTA are mostly cosmetic,” the Brookings Institute’s Geoffrey Gertz wrote shortly after the deal was unveiled. “After a year and a half of negotiations, the three parties are going to end up with a new trade deal that looks remarkably similar to the old NAFTA.” Facing resistance from Democrats and some Republicans, Trump has threatened to terminate NAFTA in order to pressure Congress to approve the deal.

The situation with China is somewhat analogous. While Trump’s trade war was partly intended to prop up U.S. industry, its primary purpose was to punish the Chinese for unfair trade practices, particularly the use of American intellectual property by Chinese corporations. To do business in China, many American companies are often required to hand over trade secrets, which are then provided to Chinese companies providing similar services. This costs U.S. companies as much as $50 billion a year. “China has engaged for a very long time in the theft of our intellectual property as well as practices like forced technology transfer,” Trump administration trade adviser Peter Navarro told CNBC earlier this year. “We’re hopeful that China will basically work with us to address some of these practices.”

“China has to open up their country to competition from the United States,” Trump said last week. “Otherwise, I don’t see a deal being made.” But in the interview in which he made those comments, Trump was unable to offer specifics for how China should “open up,” beyond generalities about taking down “barriers.” But that does not seem to be on the verge of happening—and it certainly seems impossible to resolve such a vague condition in 90 days. Instead, the White House is touting Xi’s willingness to “reduce the trade imbalance,” which is indeed massive. That’s something, but it’s nothing close to the world-historical accomplishment Trump is suggesting.

Two years into his presidency, it looks as if our major trade deals with Canada, Mexico, and China will have changed substantially less than Trump has repeatedly promised. He has followed a similar playbook in other diplomatic negotiations. He kicked off relations with North Korea by threatening nuclear annihilation; he then settled for a deal that contained, according to Global Zero’s Jon Wolfsthal, “no details, no specifics, and kicks any commitment to concrete steps down the road.” (Trump insisted that Kim Jong-un was “de-nuking the whole place. It’s going to start very quickly. I think he’s going to start now.” But North Korea reportedly has continued its nuclear program.) With Iran, Trump ripped up the nuclear deal in the hopes of renegotiating with the country—which hasn’t happened, leaving the United States to apply economic and military pressure.

The wide gap between Trump’s boasts and reality is due largely to the fact that he’s uninterested in the details of policy-making, yet demands a central role in negotiations. So he looks for ways in which he can sell the status quo as a victory. Thus far, he’s largely done so without suffering much political damage, perhaps because he has spent his first two years skating from crisis to crisis. But as the focus in Washington, and America broadly, shifts toward 2020, Trump looks increasingly vulnerable. He can no longer run on his record as a businessman. He will be forced to defend his first term in office, including the merely rebranded versions of the deals he once decried as terrible for America.

Vergangenheitsbewältigung is one of those quintessential German words: a long, clunky amalgam of syllables and ideas that expresses a concept you never imagined you’d need to name. It refers to the process of coming to terms with the past—the definitive German lexicon Duden defines it as “public debate within a country on a problematic period of its recent history, in Germany especially with National Socialism”—and it’s something of a specialty in Germany.

Since the late 1940s, with greater or lesser success, Germans have made a national pastime of owning up to individual and collective crimes associated with Nazism. It’s what made Berlin, the reunified nation’s capital, a city of memorials, where the wordy, abstract and sculptural Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe takes up central real estate alongside memorials dedicated to the Sinti and the Roma and homosexuals persecuted by the Nazis. There are bronze cobble stones known as “tripping stones” scattered around the city (and other parts of Germany), inscribed with the names of individual Holocaust victims. Then, too, there are memorials to victims of the East German state, from those who were killed trying to cross the Berlin Wall to the political prisoners who were tortured and murdered at Hohenschönhausen. The discourse of Vergangenheitsbewältigung is so developed that German has separate words for memorials that honor (Ehrenmal) and those that warn us away from repeating our mistakes (Mahnmal). Only by looking at what’s happened, by retelling the stories of the victims and the guilty, can a country begin to heal and move forward.

The arts—whether literature, film, theater, fine art, or otherwise—have reliably served as an outlet for this airing and revisiting of the past. Indeed, much post-World War II German art touches in some way on the brutality, sins, and suffering of the recent past, from Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum to Rainer Maria Fassbinder’s Marriage of Maria Braun to the epic canvases of Anselm Kiefer and Joseph Beuys’s enigmatic installations of felt and fat. There are always new angles on German history to attend to, which is why Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 film The Lives of Others was received as such a breakthrough.

At the time, precious few German films had represented a serious narrative account of the victims of the East German secret police, the Stasi. The Lives of Others told of a dyed-in-the-wool Stasi spy who realizes he might have been wrong after he becomes entangled in the surveillance of a prominent playwright and his girlfriend. A closely focused, personal story that provided insight into an expansive backdrop of politics, it was celebrated as the best film about the GDR since the fall of the Berlin Wall. It won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2007 as well as a bevy of German and European awards. It was, in a sense, a shining example of the art of Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

In his new film, Never Look Away, Donnersmarck presents another period drama, this one a portrait of the (fictional) artist Kurt Barnert as a young man. The film begins before the violence of World War II takes over, and continues through the founding of the German Democratic Republic and the construction of the Berlin Wall—the epic, tragic sweep of twentieth-century Germany. Kurt’s artistic development and personal history closely mirror that of Gerhard Richter, one of Germany’s most celebrated living artists. Like Richter, Kurt was born in Dresden and studied at the Dresden Academy of Art. Early on, Richter garnered attention as a painter of Socialist Realist murals before escaping to the West, where he continued his studies in Düsseldorf. Richter’s uncle and father were in the Wehrmacht, and he had a mentally ill aunt who was killed as part of the Nazi euthanasia campaign. As a child, he watched the firebombing of Dresden, and as a young man, he sought artistic freedom in ideologically restrictive East Germany. And yet, in spite of these many obstacles, he went on to create some of the most coveted and well-respected art of the past century.

Donnersmarck has selected Richter’s story for the artist’s success but also for his life’s drama. In an interview with the German broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk, Donnersmarck frames the question that drove Never Look Away. “For me, it’s about creativity,” he says, “to trace how someone can take their life, and the trauma of their life, and transform it into something like art.” In doing so, Donnersmarck hopes to achieve the same success as he did in The Lives of Others: to use one individual’s dramatic, tightly plotted story to reveal the impact of German history on one superlative man’s life and art.

Never Look Away begins with a tour of an exhibition at a Dresden art museum. It’s 1937, and Elisabeth, a beautiful, young blonde in a seafoam dress, leads her six-year-old nephew, Kurt, by the hand. A Nazi official in uniform criticizes modern art as a meaningless game of one-upmanship in which artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Wassily Kandinsky propose faddish, often ugly truths about the world. In his view, modern art is unskilled, decadent, and indulgent, an indignity to German soldiers and a waste of taxpayer dollars. The scene renders a slightly ahistorical version of an infamous exhibition of “Degenerate Art” that the Nazi party actually mounted in 1937, to display work they blamed for the disintegration of German culture. As Kurt and Elisabeth’s tour guide makes clear, in 1930s Germany, art was meant to glorify and purify German heritage and feeling, rather than serve as a venue for expression. The meaning and purpose of art change several times over the course of the film, often in harmony with whatever punishing ideology—nationalism, communism, or capitalism—is ascendant. Those shifts are among the film’s central themes.

After their visit to Dresden, Elisabeth and Kurt return to their still-peaceful home. But the quiet is soon disrupted: Elisabeth, a youthful exemplar of Aryan beauty, is chosen to deliver flowers to Hitler on his visit to the city, and afterward, she begins to unravel. Kurt finds Elisabeth naked at the family’s piano. She tells Kurt that the pristine beauty of the piano’s notes holds the secret to the universe. She can hear the same purity when she pounds a crystal ornament against her skull, which she does until blood trickles down her face. “Everything that’s true is beautiful,” Elisabeth tells Kurt, and admonishes him to never look away.

The meaning and purpose of art change several times over the course of the film, often in harmony with whatever punishing ideology is ascendant.Elisabeth’s psychic break is what sets the film’s dense plot in motion. Elisabeth’s illness is reported to the central medical authorities, and soon she is committed against her will to a mental hospital. Here, she turns from an individual into a cog in history: one of the hundreds of thousands of disabled or mentally ill women forcibly sterilized so as not to infect the Aryan race with inferior genes. When she learns of the pending operation, Elisabeth begs Professor Carl Seeband, the head of the gynecology department at the hospital and a member of the Court of Hereditary Health, to spare her. He remains unmoved and goes a step further: He draws a red plus-sign next to her name to indicate that she should be “relieved,” in Nazi parlance, of her “meaningless existence.”

Though Aunt Elisabeth gathers that Professor Seeband has a daughter—she appeals to his humanity by calling him “Papa”—she doesn’t know that her name is Elisabeth, too. Some years later, Kurt meets Ellie at the Dresden Art Academy. Though brunette, Ellie has the same alabaster glow and sparkling blue eyes as Kurt’s Aunt Elisabeth. Ellie and Kurt quickly fall in love, and before long, Kurt finds himself with a cruel, controlling father-in-law, a former Nazi (though he doesn’t know it yet) who has no interest in or respect for art. Unbeknownst to Kurt, he is also Aunt Elisabeth’s murderer.

Donnersmarck’s film is only loosely based on Richter—it’s not announced as a biopic—but many of the basic facts are, shockingly, true. Richter did have an aunt, Marianne, who was schizophrenic and forcibly sterilized, though she died of starvation in a concentration camp rather than in the gas chamber where Elisabeth perishes (and where Donnersmarck, to the chagrin of critics, dares to take his camera). In his thirties, Richter painted a famous canvas of Marianne as a young teen, holding him as an infant. His first wife was also named Marianne, though she went by Ema, and her father, Heinrich Eufinger, was an SS doctor who bore responsibility for the forced sterilization of some thousand women. Richter knew that his aunt died of starvation due to the Nazi eugenics campaign but was apparently unaware of the connection between his aunt and his father-in-law until an investigative journalist reported it in 2004. That Richter’s personal history contained such traumatic historical entanglements seems almost unbelievably ill-fated and, because it’s true, it demonstrates just how widespread the lingering effects of the Nazi period were. (Richter, for his part, told Der Spiegel that he has only seen the trailer for Never Look Away and found it “too sensational.”)

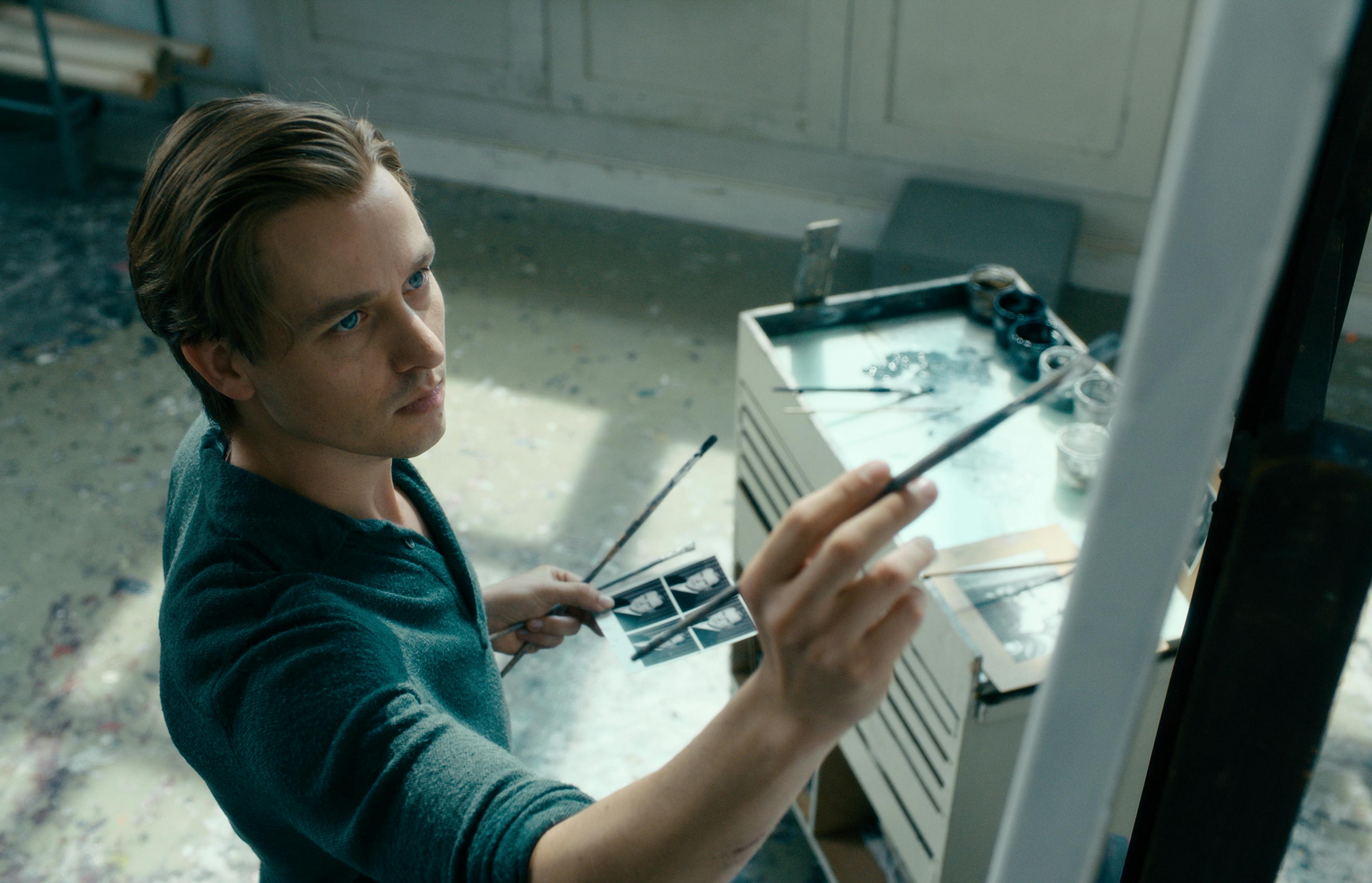

Toward the end of the film, Kurt produces a series of black-and-white paintings of photojournalism and family snapshots, blurred after the fact with horizontal strokes of a thick brush. Among these are paintings of young Kurt with his aunt Elisabeth; his uncle Günther in a Wehrmacht uniform; his father-in-law’s passport photos; an SS doctor, who was the head of the Nazi eugenics program, as he is led away in handcuffs. All of these individuals have deeply influenced Kurt’s life; likewise, they are all entangled in the crimes of the Nazis.

At one point, a strong wind blows the shutters of Kurt’s studio windows closed, causing a projection of his father-in-law’s passport photo to overlap the unfinished painting of Kurt and his aunt. Just as chance made an indelible impact on Kurt’s life, so it also plays a role in his art. Kurt makes these works after months of uncertain exploration, and it’s clear that Donnersmarck intends for us to understand them as the moment that announces Kurt’s artistic arrival.

Donnersmarck gestures at the interplay of fate and creativity with the wind-blown shutters, but in his hands that bit of chance comes out as contrived. Indeed, he ignores the fact that Richter tried to obscure the origin of his photos, in order to divorce their original meaning from that of images he rendered in paint. Richter wanted to paint the photographs, he says, partly because he saw them as “works without an author.” (This phrase, “Werk ohne Autor,” serves as the German title of the film.) As Richter told Michael Kimmelman in a 2002 interview,

When I first started to do this in the 60s, people laughed. I clearly showed that I painted from photographs. It seemed so juvenile. The provocation was purely formal—that I was making paintings like photographs. Nobody asked about what was in the pictures. Nobody asked who my Aunt Marianne was. That didn’t seem to be the point.

Toward the end of the film, Kurt says at a press conference that the tender family photographs are random, that he plucked the passport photos from a photo booth. Asked about the meaning of his work, Kurt demurs again. “My works are smarter than I am,” Richter has said, and Kurt repeats it here. “I’m not making any statements, I’m making pictures,” Kurt emphasizes.

Never Look Away is perhaps too epic, too ambitious, eager to make grand statements rather than to find poignancy and authenticity in one story.Richter’s work wasn’t expressly about making bold statements about history, his own or his country’s. He used the same blurred, photorealist techniques for numerous other subjects: curtains, cows, his children. Some of these—a clownish rendering of his father and his dog, his wife’s family on vacation at the sea—can be read as documents of a corrupted history, but they’re also just snapshots, moments in any ordinary life. Richter’s work suggests that every family has its share of hidden traumas, that all historical and personal memories are conflicted.

By contrast, Donnersmarck wants to make bold, historical statements, and that is where his film about art falters. At times, Never Look Away feels like a hulking, even unwelcome example of Vergangenheitsbewältigung. Turning over the past is such a ubiquitous activity in Germany as to have become something of a cliché there, and Germans have developed high standards for when it is useful and when it is earned. It’s telling that Never Look Away hasn’t been well received in Germany, where reviewers accuse Donnersmarck of sacrificing historical accuracy and ambiguity in pursuit of something big: the headline-grabbing Major Themes of Nazis and the GDR; another Oscar. Never Look Away is perhaps too epic, too ambitious, eager to make grand statements rather than to find poignancy and authenticity in one story.

And yet, Donnersmarck touches on something elemental about how biography, inspiration, and history can combine to create something of lasting value. In spite of Richter’s protests, it is part of what gives his photo portraits their frisson. At one point in the film, Kurt’s professor, Antonius van Verten, a stand-in for Joseph Beuys, falters in one of his lectures. In a moment of uncertainty before dismissing his students, he asks if anyone has something to contribute. Kurt bravely raises his hand. He’s been thinking about lotto numbers, he says: a group of digits that are utterly meaningless—until luck, or some mathematical probability, makes them significant. The events of the past, even coincidence, aren’t always significant, he suggests, but they can become meaningful.

The Acer ED242QR sports a 24-inch curved, VA panel that operates at a brisk 144 Hz.

The Acer ED242QR sports a 24-inch curved, VA panel that operates at a brisk 144 Hz. Microsoft may release a new Surface Laptop running AMD’s not-yet-announced Picasso chips with integrated AMD Radeon graphics in late 2019, according to a new book about the Surface brand.

Microsoft may release a new Surface Laptop running AMD’s not-yet-announced Picasso chips with integrated AMD Radeon graphics in late 2019, according to a new book about the Surface brand. Lenovo is to pay $7.3 million to a settlement fund over its installation of the Superfish adware on customers' laptops.

Lenovo is to pay $7.3 million to a settlement fund over its installation of the Superfish adware on customers' laptops. Asus has released its new 31.5-inch ROG Strix XG32VQR gaming monitor that sports the FreeSync 2 HDR badge.

Asus has released its new 31.5-inch ROG Strix XG32VQR gaming monitor that sports the FreeSync 2 HDR badge.

No comments :

Post a Comment