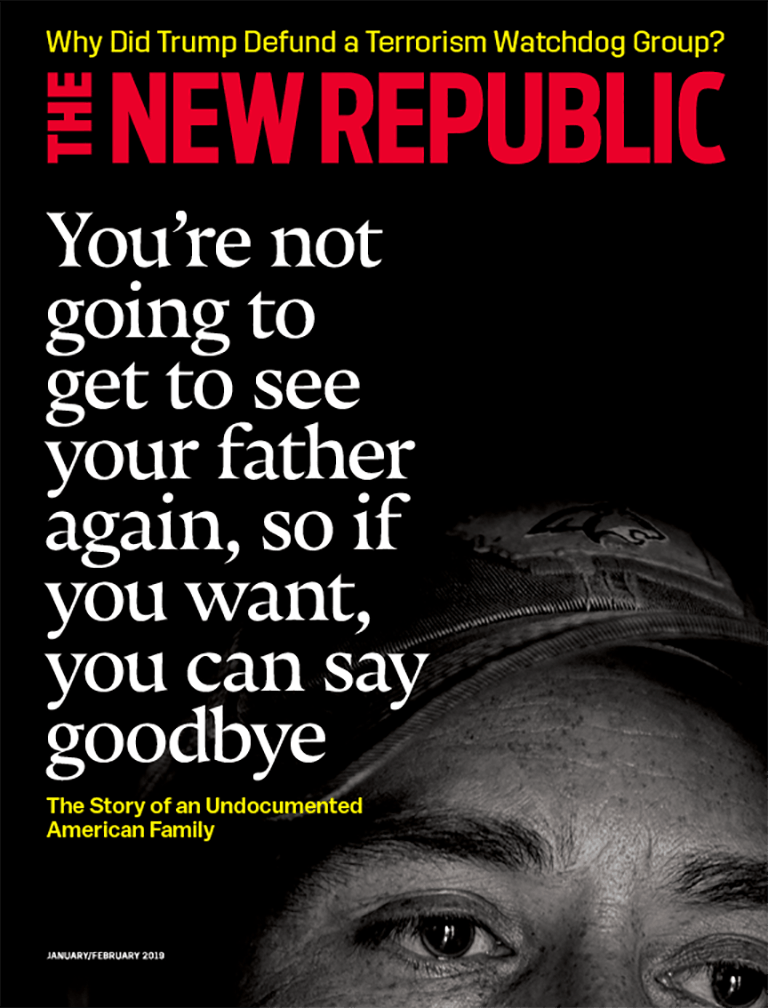

New York, NY—(December 27, 2018)—The New Republic today published its January/February 2019 issue, which features an incisive cover story by Elliot Woods. In “Jailed, Raped, Deported, Robbed,” Woods follows an undocumented man, Audemio Orózco Ramirez, who tries to return home after being separated from his wife and eight children by ICE. Trump’s executive order for ICE to take action on all known undocumented immigrants, criminals and noncriminals alike, led Ramirez to be jailed, raped while in prison, deported to Mexico and robbed at knifepoint in Tijuana. Woods explains that Audemio’s story is tragic only in its ordinariness, as there is “a generational failure to reform the American immigration system to ensure that people like Ramirez are able to live and work in the United States without getting caught up in an expensive, traumatic, and ultimately futile enforcement apparatus.”

Additional information about the January/February issue is included below.

[FEATURES]

“Mommy and Data” explores how “femtech” companies are marketing themselves to women worried about their fertility and questions if these startups are alleviating female anxieties or exploiting them. While these companies have empowered women, providing avenues to discuss desires, fears and experiences with friends and doctors while combating the stigma associated with infertility, Anna Altman asserts the science still cannot say with certainty when, how quickly, or if a woman will get pregnant. Therefore, Altman argues, “Femtech companies may be little more than a modern gloss on the health and beauty industry, applying a veneer of feminism to age-old appears appeals to women’s fears and insecurities.”

In “After South Africa’s Trump,” Eve Fairbanks discusses the striking parallels between South Africa a year after the fall of its demagogue ruler Jacob Zuma and how it could inform America’s future after President Trump. She writes, “maybe South Africa has something to teach America: how to react to a leader like Zuma, one whose hard break from the political status quo yielded outrages and disregard for the truth that seemed to amplify with each passing day. And what can happen when a society gets rid of such a man.”

[U.S. & THE WORLD]

Bryce Covert examines in “Opportunity Costs” how a tax loophole intended to help the poor, funnels money to wealthy investors. Covert explains the loophole is used by investors who fund projects in economically distressed areas deemed “opportunity zones” receive a sizable tax break, even on unrelated investments. President Trump, a promoter of the plan who accumulated at least $885 million in tax breaks, “may be the country’s preeminent expert in spotting a government handout and squeezing it for all it’s worth,” claims Covert.

“Trapped at the Border” questions if Trump’s new asylum policy, requiring immigrants to apply at official ports of entry, will turn Mexico into a holding pen for refugees. Lauren Markham details Mexico’s inability to accommodate the thousands of immigrants held on that side of the border for months at a time given the country’s limited resources and authorities’ organizational capacity. Markham states, “The government has struggled to feed, house, and clothe the refugees. Every day, thousands of people need to eat; they need medical care, jackets, and blankets; children need diapers, and women sanitary pads.”

In “Alternative Facts,” Emily Atkin demonstrates how nonpartisan research group, Global Terrorism Database of University of Maryland, lost funding from the State Department after a report regarding a rise in violence on the right drew criticism from conservatives. Atkin claims that though “Republicans have tried to bury reports about right-wing terror before, ...[t]he situation with the GTD is different, and arguably more troubling, because, as president, Trump has often pushed ideas about terrorist violence that directly contravene the available data.”

Joel Simon asks why so many journalists are dying in “Getting Away with Murder.” Simon records, “at least 34 journalists were murdered in 2018, an 83 percent increase over the previous year. The number of journalists in jail is also at record highs—251 by the most recent count.” Though there may not be one explanation for why journalists are being killed and imprisoned, the United States government’s disappointing response to these crimes helps explain why the perpetrators are acting with such impunity.

“Primary Education” describes what Democrats should learn from how Trump won the nomination. Steven Teles acknowledges that Trump identified a section of potential GOP voters who were being overlooked, while his opponents split the same 60 percent of the Republican electorate. While there are more than a dozen candidates that may run for the Democratic nomination in 2020, Teles asserts “there are (at least) four or five of them, all clustered around the same positions; come next summer, they will be fighting for the same voters, and as a result, they could all lose. It’s the same bad math that afflicted Cruz, Kasich, and Rubio four years ago, only now it’s on the other side.”

In “Strange Bedfellows,” Matt Stoller explains why antitrust is the one issue the left and right can agree on. Stoller declares, “Disdain for corporate concentration is one of the rare things in contemporary American politics that transcends ideological divisions,” even bringing the left and center together with similar critiques. Though monopoly is typically thought to be best handled by courts and economists, Stoller argues that Congress could pass laws to prevent concentration in the first place.

[BOOKS & THE ARTS]

John Fabian Witt reviews the new biography John Marshall: The Man Who Made The Supreme Court by Richard Brookhiser, which reflects on why Marshall is often considered the greatest Chief Justice in American history. Witt describes Brookhiser’s short and captivating biography in “The Operative,” stating “Marshall emerge[d] as the institution’s first great partisan operative: a man who managed with extraordinary success to reassemble a judicial branch in American government from the broken pieces of the Federalist Party. Marshall did not build the court by cantilevering it above politics.”

“Power Dynamics” from author Tony Tulathimutte examines Kristen Roupenian’s debut, You Know You Want This, a collection of 12 stories that are tied together by physiological and psychological violence. Tulathimutte states, “Although You Know You Want This may be timely in its occasional adjacency to #MeToo, its real canniness comes from apprehending the psychology not only of power, but of power-hunger as, itself, a form of weakness: how people harbor an impulse toward sadistic narcissism, and how little it takes for them to succumb to it.”

Jillian Steinhauer evaluates the oeuvre, Irrespective, by influential artist Martha Rosler, which spans her influential career as an artist with works in photography, photo-text, video, sculpture and performance. Steinhauer declares in “See for Yourself”, “gathering samples of a seemingly disparate oeuvre, the exhibition shows Rosler returning to and reexamining the same issues: gender roles, economic class, globalization. Crucially, Irrespective demonstrates how Rosler has adopted feminism not simply as a subject, but as an intellectual and artistic framework.

In “Endless Fragmentation” Alan Wolfe investigates Francis Fukuyama’s new book, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, which discusses the value of liberal democracy. Wolfe asserts, “Fukuyama’s new pessimism is far deeper than his discarded optimism. The left-right dichotomy that formerly polarized liberal democracy dealt with the question of the proper size of government; compromise, at least in theory, was always possible.”

With “Resistance Training,” Micah L. Sifry studies how L.A. Kaufman’s new book How to Read a Protest: The Art of Organizing and Resistance observes the effectiveness of the modern protest. “Ranging from the 1963 March on Washington to the mass actions of more recent years, [Kaufman’s] new book contends that how we protest—the forms of social organization embodied in these mass events—may be more important than a protest’s immediate outcomes,” explains Sifry.

Rachel Syme examines the final season of the FX comedy series You’re The Worst and how it bucks the usual finale tropes. In “Behaving Badly” Syme states “what I will tell you is that this show, which for years took every possible stab it could at the callow selfishness of its characters, ends up embracing them with empathy and understanding.”

Poems by Marcus Wicker and Garous Abdolmalekian are featured this month. For Res Publica, Editor-in-Chief Win McCormack examines how those with private interests will always prey on public resources in “A Commons Problem”.

The entire January/February 2019 issue of The New Republic is available on newsstands and via digital subscription now.

For additional information, please contact newrepublic@high10media.com.

###

Around this time four years ago, before the presidential primaries had begun, the most plausible Republican candidates seemed to be reading from more or less the same script. There were differences, to be sure, between Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Jeb Bush, but for the most part, they offered a mixture of social conservatism, budgetary austerity, and neoconservative foreign policy. Even as the field dwindled, Cruz, Rubio, and the supposedly moderate John Kasich—the last mainstream candidates left standing—all supported slashing Social Security and Medicare to make room for large income tax reductions. They were cut from recognizable GOP cloth, if tailored to slightly different tastes.

Donald Trump, meanwhile, was different, and not just in the color of his hair and the length of his ties. While all the other Republicans were converging around the policy positions of Paul Ryan, Trump identified a section of potential GOP voters who were being overlooked. It was to them that he directed his startlingly new positions on trade, immigration, foreign policy, and entitlements; for them that he promised to protect Medicare and Social Security; and for them, that he proposed a noninterventionist, what’s-in-it-for-us foreign policy, and pledged to end free trade agreements.

The majority of GOP voters—as much as 60 percent—didn’t particularly like these positions. (And GOP funders, especially those in the Koch network, saw his policy positions as an outright repudiation of their core ideological commitments.) The ordinary Republican candidates—the 16 not named Donald Trump—knew as much. But in fighting for the “normal” 60 percent of the Republican electorate, they ensured their own defeat. In Illinois, the three conventional Republicans (Cruz, Rubio, and Kasich) took 59 percent of the vote, but because it was split three ways, not one was able to top Trump’s 39 percent. The same thing happened in North Carolina, where voters gave the orthodox candidates 58 percent, and Trump took the state with 40. The strategy may not have been intentional, but it turned out to be foolproof: Carve out a distinct political ideology that appeals to a solid minority of primary voters, and let the rest of the candidates vie for, and consequently split, the rest of the vote.

More than a dozen candidates may run for the Democratic nomination in 2020: governors from the Plains states, senators from the coasts, billionaire entrepreneurs. But the most serious so far—Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, and Bernie Sanders—run the risk of falling into the same trap as the main Republicans did in 2015. All of them—even the previously ideologically flexible Cory Booker—are competing for the same section of the primary electorate, one that wants to trade in centrist triangulation for social democratic economics. Given the repeated failures of deregulation, fiscal conservatism, and crony capitalism, this is an understandable instinct. Any one of these candidates could win the nomination if he or she were the only one in the mix. But there are (at least) four or five of them, all clustered around the same positions; come next summer, they will be fighting for the same voters, and as a result, they could all lose. It’s the same bad math that afflicted Cruz, Kasich, and Rubio four years ago, only now it’s on the other side.

A recent survey by More in Common, a bipartisan think tank, identified a section of voters it called “progressive activists.” These people account for a disproportionate percentage of voters in Democratic primaries. But they are, More in Common found, just 8 percent of the American electorate as a whole. In other words, many more potential primary voters may be out there who would be open to a different kind of ideological mix than the one offered by the major Democratic candidates. And because no one is fighting for (and splitting) their share of the vote, they could end up deciding the Democratic primary.

In 1995, the writer Michael Lind argued that the center in American politics was divided between a “moderate middle” of people who are fiscally conservative but socially liberal (they’d probably vote for Michael Bloomberg) and what Lind called a “radical center” of people who are economically more left-wing—angry about the powerful moneyed interests who, they believe, have rigged the economy in their favor—but more traditional on questions of social order and skeptical of the nation’s governing elites. New America’s Lee Drutman recently found that these kinds of voters make up 29 percent of the entire American electorate. They are, essentially, the people politicians fight over in the battleground states in the general election every four years. But they are also important in the nominating contests. If a Democratic candidate could convince a sizable portion to participate in the primary, she might win the nomination.

Candidates like Booker or Warren seem to think that these kinds of voters will simply go along with an appeal designed for “progressive activists.” But it won’t work if a single candidate can offer radical centrists a package designed for them.

Say a candidate does something different: attacks the wealthy and the upward redistribution that keeps them rich, but eschews the consensus the main Democratic front-runners are pursuing, with their proposals for job guarantees, single-payer health care, and mandatory worker representation on corporate boards.

Instead, that candidate suggests policies that strip away the subsidies that pad the incomes extracted by the finance and asset management industries, from low capital requirements to massive tax handouts for IRAs and 401(k)s. She might work to prevent large firms from shaking down states and localities, be it through sports franchises or Amazon’s ugly HQ2 lottery. Or she might attack the ways in which the wealthy have used zoning laws to make New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., the equivalent of gated cities. Or she could break with the emerging orthodoxy on how to control the cost of medical care and propose driving down the pay of doctors by loosening licensing requirements and stripping the American Medical Association of its power over prices in Medicare. She could, in short, attack economic inequality at its source, but in a way that doesn’t read quite as tribally left as the proposals of Warren, Booker, and Harris.

The radical center wants a party that supports existing social insurance programs and offers up ideas for even more, such as vastly increased child and earned income tax credits or universal catastrophic health insurance. These policies would substantially redistribute income, which the radical center would like to see, without raising worries about what the government can actually pull off.

While economics is central to the appeal that such a Democratic candidate might deploy against the rest of the field, he or she will also need to find a way to cut into the social order issues—especially crime and immigration—that Trump deployed with such force in 2016. The trick is to do so in a way that treats the concerns of less traditionally liberal voters seriously without sticking a finger in the eye of core Democratic constituencies. On immigration, this means putting the focus of enforcement on employers by promising to uphold the nation’s labor laws vigorously, rather than offering the Trumpian package of deportation and a border wall. Where criminal justice is concerned, a mayor or governor with a solid record on crime could argue for funding better-trained police forces and introducing a significantly upgraded parole and probation system as an alternative to mass incarceration. Such a candidate could emphasize that minority voters consistently want greater safety, as well as a more equitable criminal justice system, and offer to give them both.

The majority of Democratic voters may not prefer this mix—but a single candidate offering it might get enough votes to win the primary. If a Democrat is going to do what Trump did to the Republicans—compete for overlooked voters—it will be because she offered something very different from the other candidates and joined parts of the electorate in a way that no one has tried before. This political combination does that, and it has enough economic-populist spirit to grab at least some people on the left, especially if a candidate puts these issues in the language of genuine anger at irresponsible elites.

Such a candidate may not exist. But the potential Democratic contenders, like Joe Biden or Amy Klobuchar, who have not yet fully attached themselves to the left’s agenda, could incorporate at least parts of this appeal. And there may be an opening for a purer version of this ideologically unorthodox Democrat, especially someone like outgoing Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper or former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who has not yet developed a clear political brand. An unknown may have no chance competing against a single familiar politician, such as Booker, Warren, or Harris. But in a traffic jam of such candidates, a candidate like this might be able to squeeze through to victory. It worked for Trump, and there’s a chance it could work again.

From the outside, the New Mexico Cancer Center looks like any other outpatient clinic: Each week, hundreds of cancer patients travel to the nondescript tan and turquoise building in an Albuquerque office park just off the interstate for tests and treatments. But unbeknownst to many of them, it has become a flashpoint in a legal battle over the future of health care in the United States. The Cancer Center’s CEO and co-founder Barbara McAneny, an oncologist, has long accused New Mexico’s dominant health system, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, of using its size to force her out of business—and now she and her colleagues are suing in the U.S. District Court in the District of New Mexico to break the health system apart.

The fight pits these two businesses against one another, but it is also a clash over the best way to deliver health care in the United States, as embodied by two of the country’s most powerful health care interest groups. Earlier this year, McAneny became president of the American Medical Association—and as such, perhaps the nation’s most prominent physician. And although he recently left to head another health system, the longtime CEO of Presbyterian, Jim Hinton, served as the chair of the American Hospital Association while the lawsuit advanced.

Filed in 2012, the case has already ground along for more than half a decade of legal motions and a lengthy discovery phase, not atypical in an antitrust case of this complexity, and the parties now wait for the judge to set a trial date. The outcome of the case will affect not only where New Mexican cancer patients get treated, but whether giant health care businesses across the country will be allowed to continue growing unchecked, in the face of diminishing competition. According to an index used by regulators, 90 percent of metropolitan statistical areas have hospital markets that are so “highly concentrated” that the lack of competition warrants scrutiny, and 65 percent have highly concentrated specialist physician practices, as well.

“Consolidation can be a perfectly good thing,” said Martin Gaynor, a professor of economics and health policy at Carnegie Mellon University. In theory, economies of scale can eliminate redundancies and allow for better coordination. “But it’s also very important to bear in mind that healthcare is a business—and healthcare is a really, really big business.” Like other monopolies, health care companies are more than capable of using their market position to inflate prices, and experts increasingly say that lack of competition is one of the main reasons why health care costs in the United States are so high, consuming nearly one fifth of national economic output.

With every new blockbuster merger between ever-larger health care businesses, regulators must consider whether they are expanding to deliver better care at lower cost, or merely extinguishing competition to bend the market to their will. And that, in part, is what this lawsuit is set to decide.

Founded by a minister in 1908 as a sanitarium for tuberculosis patients seeking cures in the dry desert air, Presbyterian began to take its modern form in the 1960s when the first brick buildings of the hospital’s central campus were erected. Jim Hinton, an Albuquerque native, began a residency in hospital administration there in 1983. Charismatic and good at organizing people, he rose through the ranks quickly, and in 1995, the board elected him CEO. He was 36 years old.

New Mexico is tough terrain in which to grow a health care business. The state has among the highest rates of liver disease, teen births, and diabetes in the nation. Delivering care there means covering vast distances—of New Mexico’s two million residents, a quarter are spread out over extensive rural areas and distant from city hospitals—and there are few resources to pay for it. With one in five New Mexico residents living below the poverty line, health care providers treat a population more reliant on public insurance than in any other state, a situation that cuts into their margins. (Medicare and Medicaid reimburse less than private insurers would for the same services).

But New Mexico has also been on the leading edge of the business of health care. Until the 1990s, hospitals in the United States typically provided care and billed outside insurance companies for it, but during that decade hospitals in Albuquerque were among the first to begin offering their own health insurance plans. As so-called managed care organizations, the theory went, these hospitals would be incentivized to keep their insured patients healthy and out of the hospital, avoiding unnecessary care that came of doctors billing and ordering extra procedures. But the new structure also meant that these organizations got to decide which practices and physicians they would work with, and which to exclude. And the power to influence where insured patients receive treatment could also be used as a weapon against competitors, as Hinton would demonstrate early in his tenure.

In 1997, Presbyterian purchased an insurer, Family Health Plan, whose 58,000 members meant the hospital now controlled the largest health plan in the state. Before they were folded into Presbyterian’s network, those people had been able to go to any regional hospital; now Presbyterian told them their care would only be covered if they went to one of its own facilities. This was a brilliant strategic move in the eyes of Barry Silbaugh, who was a physician vice president for a rival hospital, St. Joseph’s, at the time. In effect, the merger deprived St. Joseph’s of crucial income, ultimately driving it out of business. “Most hospital executives would not think of that, in my opinion, but [Hinton] was thinking as an insurance executive.”

Hinton also pushed Presbyterian to acquire physicians. Outside doctors had long brought their sickest patients to his hospitals, which essentially served as workshops where they drew on the intensive care services only hospitals can provide. But as new regulations made it more onerous for clinicians to run their own small private practices, Presbyterian offered to make them permanent employees—strong-arming them to accept, if necessary

Allyson Ray, an ear, nose, and throat doctor in private practice in Albuquerque, had treated Presbyterian-insured patients for years when the health plan abruptly cut its reimbursements for her services. When she and colleagues grouped together to negotiate, she said Presbyterian informed them it would rather pay higher prices to send patients for treatment out-of-state than compromise with them. The incident added to New Mexico’s perennial shortage of specialist physicians: rather than endure the confrontation, Ray recalled, one of the doctors left the state and another retired early.

Presbyterian also restricted the technologies clinicians could use in the hospital without their input about how it might affect outcomes. “From my viewpoint it was mostly for the benefit to build their business,” Ray said, “and they didn’t seem to show any concern for quality of care.”

General surgeon Robert Milne said that when he left private practice for a job at Presbyterian in 2003, it didn’t immediately affect the care he delivered; he was able to refer patients to doctors he trusted, whether or not they, too, were Presbyterian employees. But then things began to change: “That was discouraged,” he said, and over time, “they became more insistent.” While it would seem logical for an insurer to seek out the best services at the lowest cost, Presbyterian preferred dealing back to its own staff. As another doctor put it to me, they didn’t care what they paid; they care who they paid.

In a history of Presbyterian issued on its centennial, Hinton said such criticisms were a misreading of the events. “I think independent specialty physicians saw that Presbyterian and the health plan were growing and may have felt that we would use our size to their detriment. Well, that was never our intent.” Whatever the intent, the number of physicians employed by the system has swelled — from 42 in 1995 up to over 650 today.

With 11,000 total staff, Presbyterian is now the largest private employer in the state, and it insures one in three New Mexicans. As Larry Stroup, who was chairman of the board when it named Hinton CEO, told me recently, “If I didn’t have that level of understanding and appreciation of Presbyterian, if I was on the other side of the competitive environment in Albuquerque, I would claim that it is an unbalanced market.”

Leading a tour of the Cancer Center, Barbara McAneny strides the corridors with easy command. The word most people settle on to describe her is “tough.” (In her speech on taking the reins of the American Medical Association, she quoted Sylvia Plath: “I don’t believe the meek will inherit the earth; The meek get trampled and ignored.”) Little escapes her. Ducking into an empty exam room, her gaze quickly settles on a scuff mark behind the door where a chair has rubbed against it, and she frowns. An avid gardener, she points out a spot through a window where she’d planted rose bushes in the dry desert earth—until she realized the only people enjoying the flowers were those who stepped outside to smoke, and she paved it over to make more clinical space.

This site was nothing but dirt when McAneny first entered private practice in 1983, the same year Hinton took his first job at Presbyterian. A few years later, she teamed up with a fellow oncologist, Clark Haskins, and their group quickly earned a reputation for providing excellent care, traveling to the peripheries of the state to bring services closer to rural patients. At that time, it was difficult to treat most cancers in outpatient settings, so the partners referred them to the city’s hospitals and cared for them there. As Haskins recalled, “She and I were #1 and #2, as far as admitting patients at Presbyterian and St. Joseph’s hospitals, for several years.”

McAneny and Haskins made a series of canny decisions to build their own business, and soon, they weren’t just cooperating with Presbyterian, they were competing with it. New anti-nausea drugs had recently hit the market, which allowed a growing share of cancer patients to be treated in their own doctor’s office, rather than a hospital, so McAneny and Haskins gradually referred fewer patients to Presbyterian. In 2002, they opened their New Mexico Cancer Center to provide outpatient care with an extensive array of ancillary services. On the walk-through today, McAneny points out the CT scanner and linear accelerator with evident pride, explaining that having these costly apparatuses on-site means a patient who comes in anxious about an unidentified growth can get immediate answers.

The Cancer Center will earn a healthy profit from those evaluations, but its most lucrative revenue stream comes from selling drugs. Typically, doctors prescribe medications that are then sold by pharmacists, but oncologists operate in a different way: They are allowed to both prescribe chemotherapy drugs and sell them, earning a share of the drugs’ price, which is often considerable (according to the Community Oncology Alliance, a single doctor may prescribe $5 to $6 million of drugs annually).

This arrangement has made private oncology practices tempting targets for acquisition, and federal policies give hospitals further reason to gobble them up. Presbyterian and thousands of other hospitals that are eligible for what is known as the 340B program can buy drugs from the manufacturer at a 23 percent discount— and when they dispense them, they can tack on additional ‘facility fees.’ This means that merely purchasing an outpatient facility and designating it as ‘hospital-based’ can vastly increase its revenues—with no change to its operations. And higher revenues are what justify the sky-high salaries of administrators who run these ostensibly nonprofit organizations: tax records show that Jim Hinton received $9.8 million between 2013 and 2016, making him among the highest-paid people in New Mexico.

These trends can be seen across the country, as oncology practices are swallowed up at a rapid pace. A 2018 study in Health Affairs found that 54 percent were integrated into hospitals or health systems in 2017, up from 20 percent in 2007. (There is debate about the degree to which the 340B program has driven the integration but a 2018 study in The New England Journal of Medicine found more than double the number of oncologists working in hospitals eligible for the program than in those that were ineligible.) And this explains why, shortly after the Cancer Center opened, Presbyterian allegedly began taking actions to acquire it.

McAneny said that at first, Presbyterian plied her group with offers to hire them. But, leery of the loss of autonomy they had seen other doctors experience on becoming employees of the health system, she and her colleagues demanded a degree of control that Presbyterian wasn’t willing to concede. Then, McAneny alleged, Presbyterian tried to run them out of business.

In the lawsuit she and her partners filed in June 2012, they claim the Presbyterian health system directed its physicians to cease referring patients to the Cancer Center. The doctors had a contract with Presbyterian’s health plan that allowed them to treat the patients it insured, but in the complaint, they allege that the health system threatened to terminate that agreement. Presbyterian also allegedly told patients that, to be reimbursed for care they received at the Cancer Center, they would have to fill their prescriptions for chemotherapy drugs at the hospital’s pharmacy, which would have undercut the Cancer Center’s main revenue stream.

Jason Mitchell, the Chief Medical Officer of Presbyterian, declined to comment on the lawsuit but maintained that the health system had no problem working with private practitioners in the community. “We’re very collaborative,” he said. “I think it’s critical that we maintain our community providers and their practice.”

There’s no consensus about whether cancer patients treated by a hospital fare better than those treated by independent physicians, but it’s clear that they pay more. A 2017 study found that cancer patients with commercial insurance who were treated in hospital outpatient settings paid prices that were 50 percent higher than those treated in doctors’ offices. And a 2018 study in The Journal of Health Economics found that the price of physicians’ services rose 14 percent after they were acquired by hospitals. Barak Richman, a professor of law at Duke University, said this is typical of how the way we bill for health care can distort the way it is delivered. “We encourage treatment in the wrong places: places that are incapable of giving higher-quality care and are wildly capable of imposing higher costs.”

According to McAneny and her colleagues, Presbyterian’s predations are rooted in its monopoly power, and the only true solution is to break it into its constituent pieces. “I want to take them apart,” McAneny said. “I want the hospital to go back to being a hospital. I want the health plan to go back to being a health plan. So every physician—whether independent or Presbyterian—can compete on quality and cost and not on who signs their name on the paycheck.”

But while the Federal Trade Commission has been relatively active in challenging “horizontal” mergers that consolidate similar businesses (when one hospital system acquires another, for example), they rarely intercede to block “vertical” mergers between different business types (as in the case of Presbyterian, which fuses doctors, hospitals, and insurance). “I don’t think that all of healthcare needs to be done by these large vertically-integrated institutions,” McAneny said. “I’m coming to the conclusion that there’s a right size for healthcare that varies based on your community.” Were the courts to rule in her favor, it might draw public attention to this position, and ultimately push regulators to take more aggressive action.

To be sure, it is impossible to ignore the financial interests that McAneny and her colleagues have in the outcome of the case. While they may be fighting for changes they believe will reduce the public’s health care expenses, the viability of their own business also hinges on the outcome. And there’s something personal at stake, too. McAneny and doctors of her generation mourn a culture of medicine they see slipping from their grasp: as health systems have expanded and grown more reliant on data to make clinical decisions, care has become fragmented across ever-wider teams and doctors have lost some of their centrality. McAneny can’t hide her disdain for the hospital administrators who have gained authority as a result; she described their main duties as “making sure there are meals provided to patients and the floors get cleaned.” David Stryker, an infectious disease doctor in private practice who has contracted with Presbyterian and served on one of its boards for over a decade, put it succinctly: “When I started practice, the hospitals were there to help me take care of my patients. Now, I’m there to help the hospital serve their customers.”

A single lawsuit is unlikely to turn back the tide. In a preliminary decision in 2014, a federal judge found that the Cancer Center made a plausible antitrust claim and allowed the case to move forward to discovery; they now await a trial date. But even if the District Court ultimately rules in the doctors’ favor, there is a limit to how much that will achieve. Health systems across the country are growing ever more concentrated, dominant in their own marketplaces and with economic weight to move markets in neighboring ones. Reversing these trends would almost certainly require regulators invigorated to push back hard against them, and legislators willing to dismantle the federal policies that promote consolidation in the first place.

Or perhaps the concentration will reach a point that it spurs policymaker to adopt an even more radical fix. “I have personally been a diehard conservative most of my life,” said Bill Fitzpatrick, a former Chief Medical Officer of Presbyterian, “but Bernie Sanders may have it right: we may need a single payer system.” In today’s fragmented health care marketplace, with competition mostly limited to behind-the-scenes negotiations between huge payers and providers, rent-seeking behavior is rife. Though costly, a sole public insurer might eliminate the worst of these inefficiencies.

While the parties to the lawsuit await trial, Presbyterian has continued its expansion unabated. In September, it opened a $145 million hospital an hour up the highway in Santa Fe, which many see as unneeded additional infrastructure but the requisite toehold for entering that new market. “I can already see the wars coming up there in terms of who is going to have the medical doctors and who is going to have the patients,” Fitzpatrick said.

But it is no longer on the watch of Jim Hinton, who finally left New Mexico in 2017 to head Baylor Scott & White Health in neighboring Texas, with about five times the annual revenue of Presbyterian. Few of his old peers were surprised when in October 2018, he announced the acquisition of the neighboring Memorial Hermann Health System, to create a sprawling network of 68 hospitals.

No comments :

Post a Comment