A few weeks after President Donald Trump moved into the White House, he received a memo from one of his biggest campaign donors: Robert Murray, the CEO of Murray Energy, America’s largest private coal company. Emblazoned with the words “Action Plan,” it was essentially a wish list of all the environmental regulations Murray wanted Trump to get rid of.

Nearly two years later, Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency is on track to fulfill almost all of Murray’s requests. And the Senate is on the cusp of allowing one of Murray’s most trusted former lobbyists to lead the effort.

On Wednesday, the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works held a confirmation hearing for Andrew Wheeler, Trump’s nominee to run the Environmental Protection Agency. Wheeler has been effectively running the agency as acting administrator since July, when Scott Pruitt resigned amid a deluge of ethical scandals. But Trump only formally nominated Wheeler to lead the EPA last week, triggering a confirmation process that Democrats are using to shine light on an unsavory fact: As a lobbyist for Faegre Baker Daniels, Wheeler earned more than $700,000 working for an industry he’s in charge of regulating.

The Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to care about this potential conflict of interest, because they’ve confirmed Wheeler before; his ascent to EPA acting administrator was an automatic promotion from his Senate-confirmed role as deputy administrator. But Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse used Wednesday’s hearing to argue that Wheeler had hidden information from the Senate about his relationship with the coal company.

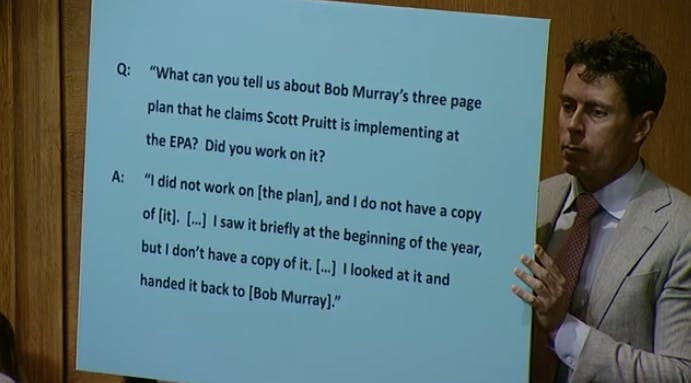

During his confirmation hearing in November 2017, Wheeler said he “did not work on” Murray’s “Action Plan” for Trump, did “not have a copy” of it, and that he only saw the plan “briefly at the beginning of the year.” These comments were featured Wednesday on a large poster board held by a Whitehouse staffer.

epw.senate.gov

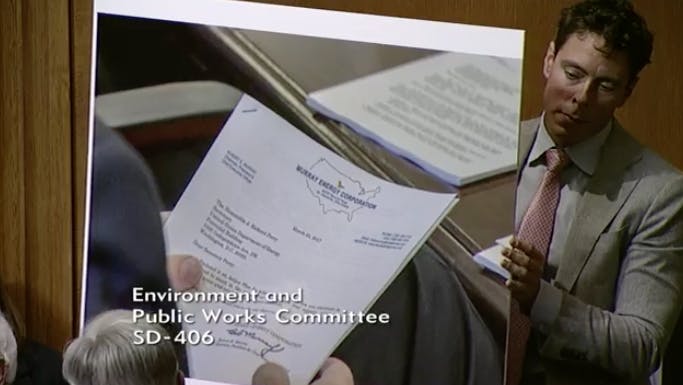

epw.senate.govAs The Washington Post later revealed, Wheeler attended a meeting in March 2017 with his then-client, Murray, and Department of Energy Secretary Rick Perry. “The action plan was right there in the room,” Whitehouse said while his staffer displayed the photographic evidence.

epw.senate.gov

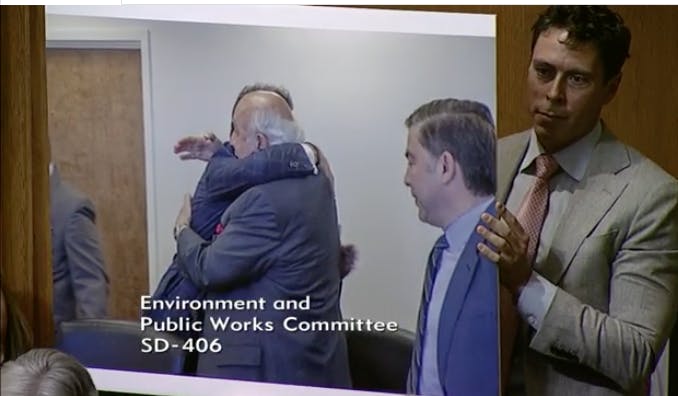

epw.senate.govWhitehouse then showed a photo of Perry and Murray at the end of the meeting, embracing in a “bear hug.”

“That’s not me, though,” Wheeler said.

“No, that’s your client, Mr. Murray,” Whitehouse replied.

epw.senate.gov

epw.senate.govGood government advocates say it’s not inherently unethical for a former industry lobbyist like Wheeler to lead the EPA. What’s unethical, they say, is if the former lobbyist continues to work for the benefit of their former client instead of the public.

Murray seems to believe Wheeler will continue to do what he wants. “He worked for me for 20 years,” he told Politico last year. “Didn’t want to lose him. But the country has him.” And so far, he’s right. As Mother Jones reported on Wednesday, “The last major action Wheeler took before his agency shut down late last month was remove the legal justification for the EPA’s regulation for mercury, arsenic and air toxics, a move that weakens the EPA’s position in a court case pursued by, yes, Bob Murray.”

The key question for the Senate is whether Wheeler, as the head of the EPA, would willfully ignore the public interest in order to please his former client. Senate Democrats certainly think he would, which is why they spent much of their time Wednesday grilling Wheeler on climate change and criticizing him for weakening several Obama-era rules to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Wheeler has proven to be a quieter, less controversial figure than Pruitt—and potentially a more effective one. Under Wheeler’s rule, the EPA has proposed weakening methane pollution limits for oil and gas producers and air pollution limits for cars. The agency has also proposed new greenhouse gas regulations to replace the ones implemented by Obama’s EPA, which could be worse for the climate than having no climate rules at all.

Pruitt was planning on doing all those things, too. But many have argued that Wheeler understands the administrative and legal processes better than Pruitt, and thus can implement deregulatory rules that more effectively benefit industry and withstand court challenges. And unlike Pruitt, Wheeler hasn’t been making daily headlines for booking expensive first-class travel, keeping secret calendars, or installing $43,000 soundproof booths.

Wednesday’s hearing didn’t alter that impression. Wheeler proved that he’s deeply knowledgeable about the energy industry and EPA regulations, and that he’s more politically adept than his predecessor. When Senator Bernie Sanders asked him about climate change, he did not deny its reality. “I would not call it the greatest crisis, no sir,” Wheeler said. “I would call it a huge issue that has to be addressed globally.” It was an innocuous response that lent itself neither to outraged headlines nor furious tweets from his soon-to-be-boss.

There’s an intriguing phenomenon in publishing you could call the One Great Idea book. Usually written by a leading senior scholar in an interdisciplinary field such as international relations, political philosophy, or comparative literature, the One Great Idea book displays a command of numerous languages and wide-ranging familiarity with classics in philosophy or religion. Its major aim is to reduce our understanding of complex realities by identifying one guiding thread that helps unravel the mystery with which it is concerned.

IDENTITY: THE DEMAND FOR DIGNITY AND THE POLITICS OF RESENTMENT By Francis FukuyamaFarrar, Straus, and Giroux, 240 pp., $26.00

IDENTITY: THE DEMAND FOR DIGNITY AND THE POLITICS OF RESENTMENT By Francis FukuyamaFarrar, Straus, and Giroux, 240 pp., $26.00 In the modern world, the best exemplar of the One Great Idea book is Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. Although it was published in two volumes, and contains insights on subjects as different from each other as federalism, the education of young women, and military discipline, Tocqueville’s masterpiece was dominated from start to finish by one and only one idea: that democracy had, mostly problematically, influenced every area of American life. Unlike the Enlightenment thinkers who preceded him (Voltaire, for example, wrote poetry, drama, history, philosophy, and even theology), Tocqueville made no effort to master all the available genres. His Recollections, unlike Rousseau’s Confessions, are not especially personal and are confined to a limited period in his life: the French Revolution of 1848. He, in contrast to Diderot, would edit no encyclopedia. And though his other books, especially The Old Regime and the Revolution, are still read and debated, it was Democracy in America that put forward a unifying theory.

We do not have many Tocquevilles among us in the contemporary world. The country of his birth, France, comes closest to keeping alive the tradition of what one French philosopher, André Glucksmann, called “the master thinkers.” (Glucksmann wrote to warn against them.) We can now trace the roots of many of these to one of the most captivating intellectuals of the twentieth century: the Russian-born French philosopher and civil servant Alexandre Kojève, whose seminars on Hegel in the 1930s shaped the way Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Louis Althusser, and others too numerous to mention understood the world.

A Marxist, but of the most unorthodox variety, Kojève taught that there was direction and meaning in history and that the key to understanding both of these lay in an appreciation of Hegel, whose vision of the dialectic imagined a state of eventual universality, the highest form of human consciousness, in which individual finite selves would be tied together in a spiritual recognition of each other. Kojève’s command of languages and his range of interests were superhuman; he wrote about Buddhism, quantum physics, ancient philosophy, and the paintings of his uncle Wassily Kandinsky. A policymaker as well as a philosopher, Kojève was instrumental in creating the free trade policies of the West in the years after World War II. He also may have been (the charge is widely disputed) a Soviet spy during the 1940s. His life is the stuff of which movies—at least French movies—are made.

One of Kojève’s most important interlocutors was the German-born American political philosopher Leo Strauss; the two argued over many subjects, none more vigorously than Xenophon’s dialogue Hiero. Strauss did not keep Kojève to himself: One of his best-known students, Allan Bloom, studied with and wrote about Kojève, calling him “the most brilliant man I ever met.” In Ithaca, New York, the trail of influence continued unabated. In one of Bloom’s last classes at Cornell sat the future foreign policy specialist and political thinker Francis Fukuyama.

After Cornell, Fukuyama went on to Harvard to study with such distinguished political scientists as Harvey Mansfield and Samuel P. Huntington. He then took a job on the policy planning staff at the U.S. State Department, before moving on to a distinguished academic career. Bloom had done Fukuyama the greatest of favors by introducing him to Kojève’s thought: As it happened, the editor and publisher of The National Interest—Owen Harries and Irving Kristol, respectively—were looking to publish a One Great Idea journal article to help the fortunes of their magazine. Fukuyama had submitted something on “the end of history.” The piece amounted to an English-language summary of Kojève’s main writings, leading Fukuyama to the conclusion that Hegel’s universal synthesis would be realized in politics through the eventual triumph of liberal democracy across the world. Harries not only published the essay, but surrounded it with reactions from the crème de la crème of the American foreign policy establishment.

So began, or more properly sped up, the phenomenon of “endism”: bold declarations announcing that history will never again be the same. (Daniel Bell may have started the contemporary craze with The End of Ideology, published in 1960.) By the time Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man—a book expanding on his essay—in 1992, everyone that mattered wanted to debate the idea that history had reached its logical conclusion and in particular that democracy proved a more stable form of government than totalitarianism. At long last, Kojève had arrived in America.

The End of History was both bold and stimulating; I remember my deep absorption in all the complexities of his argument, so refreshing in comparison to the vapid hypothesis-testing of the political science profession. Whereas most One Great Idea books tend to present gloomy, Puritan-like sermons about how far we have fallen, this one shook up such pessimism. It forced a rethinking of the value of liberal democracy and the success of modernity. We had no need to accept the utterly bleak worldview adopted by the children of Nietzsche such as Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. The world, Fukuyama reminded us, was not going to hell in a handbasket.

The only flaw in the brilliance of The End of History was that its thesis turned out to be wrong, and wrong in a huge way. For one thing, China found a way to produce rapid economic growth while bypassing democracy. The Soviet Union did indeed collapse, but far from turning to liberal democracy, it gave us something more closely resembling fascism. And even the liberal democracies themselves have witnessed growing inequality and political instability. The theory’s particular failures also revealed a major problem with the One Great Idea book: If the one great idea turns out to be wrong, everything else in the book is likely to be ignored.

At a time of populist unrest, bitter political polarization, and rampantly spreading authoritarianism, Fukuyama’s book now appears to have been written for another planet. Far from avowing the triumph of liberal democracy, in 2019 many believe we will be lucky to hold on to the dwindling number of liberal democracies we have. And the force that may do us in appears to be the very opposite of Hegel’s universality: the obsessive particularism of ethnic identification.

Perhaps understanding the possibility of obsolescence, Fukuyama has worked hard to keep his idea alive. He published other books, none of them so intensely discussed, in which he adjusted his thesis to account for new events and in particular to place a greater emphasis on culture at the expense of economics. In the preface to his new book, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, he returns once again to the controversy he started and tries to defend himself against (unnamed) critics. Those critics, he maintains, simply misunderstood him; by “end” he meant a target or a destination, not a literal ending. Besides, he writes, the original article had a question mark at the end of its title (although the book, which attracted far more attention, did not). This is another problem with the One Great Idea book: The author has invested so much in what he has written that he has to perform exceedingly lame twists and turns later just to keep it on the playing field.

Perhaps the most significant concession that Fukuyama’s new book makes is its lack of world-defining ambition. Identity runs to scarcely half the length of The End of History. It does emphasize the importance of identity, but not to the exclusion of everything else. Its chapters are short and to the point. Older and wiser than when he wrote his most famous work, Fukuyama is less given to grand pronouncements. Identity is merely a book, not a blockbuster.

To be sure, Fukuyama’s new book does contain a thesis. As it happens, the new idea stands in the sharpest possible contrast to the older one. Liberal democracy, far from showing us a glimpse of a universalist future, now, we are told, faces a severe crisis. Rapid economic growth makes contemporary liberal democracies attractive destinations for people seeking a better life. But the resulting diversity, furthered by the new groups seeking recognition, is attacked by groups already in the home country as a lowering of their status. “The retreat on both sides into ever narrower identities threatens the possibility of deliberation and collective action by the society as a whole,” he writes. “Down this road lies, ultimately, state breakdown and failure.” With the rise of ethnic politics, there may soon be few if any liberal democracies left. The particular has completely subsumed the universal.

Fukuyama’s new pessimism is far deeper than his discarded optimism. The left-right dichotomy that formerly polarized liberal democracy dealt with the question of the proper size of government; compromise, at least in theory, was always possible. Today, he argues, we are dealing with problems of recognition and resentment, and they are more difficult to resolve. As Fukuyama pithily puts it: “either you recognize me, or you don’t.”

On this key point, I believe, Fukuyama is incorrect. Partial recognition is not only possible—it is common. Biracialism, religious syncretism, and the invention of traditions all allow for compromises over identity. In fact, what we witness in one country after another in today’s world is an astonishing blending of elements once considered fixed: the crumbling of racial and religious sameness on display at the latest wedding of an English prince; the popularity of new age religious rituals and rhetoric; the celebrated successes of the diverse French soccer team; the composition of any major symphony orchestra. Identity may be important, but identity is fungible. We make what we are.

This is not a position to which Fukuyama subscribes. Rather than treating collective identities as works in progress, he views efforts at recognition such as nationalism or religious fundamentalism as residing in, of all places, the human soul. To appreciate the power of such forces, he writes, we need to return to Socrates and the stress he placed on thymos, or the need to be treated as worthy by others. (Fukuyama included a discussion of thymos in The End of History.) Under modern conditions, moreover, people not only want recognition from their peers, they want a feeling of self-worth as well. If we are to understand why Syrians are being killed, why Croats and Serbs continue to distrust one another, why Ukrainians despise Russians, and even why Donald Trump was elected, thymos may provide the answer.

It is widely believed that another One Great Idea book, Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations, which foresaw a new era of divisions and conflicts, was written in response to The End of History. In Identity, Fukuyama concedes the debate to his former teacher. Indeed, he goes beyond him. For Huntington the clash of civilizations was primarily cultural, a struggle between the competing traditions and worldviews of the West, the Islamic world, and China. For Fukuyama the clash over status, when it isn’t governed by thymos, “is rooted in human biology” and therefore unlikely ever to disappear. “Our present world is simultaneously moving toward the opposing dystopias of hypercentralization and endless fragmentation,” he concludes. It is difficult to be more pessimistic than that.

For all its failure to make accurate predictions, The End of History dealt at least with the future. Not many thinkers were discussing the end of history when Fukuyama began, and that fact contributed to the uniqueness of his book. Identity is not like that. Almost nothing in Fukuyama’s book is new: Charles Taylor (whom Fukuyama cites) has written about the politics of recognition, and a host of writers far too numerous to credit here have written about ethnicity, borders, globalization, strong religion, and every variety of nationalism. Identity summarizes arguments that already seem dated. It is, moreover, primarily concerned with the recent past, and when it ventures to make a prediction, it simply carries current trends into the future.

Uncovering trends is valuable even if there is no guarantee that the trends will continue. You can be wrong and still change the world.

What, moreover, are we to do with the political conflicts raised by identity politics? Here too Fukuyama’s analysis is disappointing. He blames both the left and the anti-immigrant right for their unbending attachment to “understandings of identity based on fixed characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and religion.” But the left (and for all I know the right) is divided between essentialists who hold that race and gender are fixed and the social constructionists who believe the exact opposite. He even claims, against all evidence, that our present stalemate over immigration is caused by those who oppose any form of “amnesty” and those “opposed to stricter enforcement of existing rules,” when in fact it is on the right, and the right only, where intransigence and unyielding intolerance reigns. I agree with him that, in theory, it is easy to imagine trade-offs that can improve America’s dreadful policies toward immigrants. But to realize them, we need to explore the disproportionate influence of rural areas and the South in Congress, the failure of leadership in the Republican Party, the obdurate persistence of racism, and other messy realities that do not find much expression in this book.

The contrast between Fukuyama’s first book and this one raises a question of form as well as content. For writers of nonfiction, getting reality wrong would seem to be the biggest imaginable sin, a luxury allowed to fiction writers but not to us. Simply being wrong, however, is not Identity’s major problem. The End of History was wrong, but it was also stimulating, breathtakingly ambitious, a paean to the importance of ideas. Karl Marx got his One Great Idea—that the future belonged to communism—wrong, but he is not therefore, in the famous words of Paul Samuelson, a “minor post-Ricardian.” History befuddles all who write about it. Uncovering trends is valuable even if there is no guarantee that the trends will continue. You can be wrong and still change the world. Identity, by contrast, both begins and ends with a whimper. Nothing is startling and little is gained.

Give me The End of History over Identity any time. Rehashing is not Fukuyama’s strength, but that is what he does here. I am no better at predicting the future than anyone else, but I am willing to bet that in five years, Fukuyama’s Identity will be all but forgotten. That will be a shame. We lack great One Great Idea books. I hope there is out there someone in his or her thirties or forties willing to take a chance on something that will have us talking as long as The End of History did.

In the wake of Bernie Sanders’s loss to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic primary, some people argued that, as Vanity Fair put it, he “won in the end” because his race had “a profound, and lasting, effect on his party.” This was not a fanciful idea. The Vermont senator’s “revolution” had succeeded beyond progressives’ wildest expectations, pushing the party leftward on health care, climate change, economic redistribution, and foreign policy. Since Barack Obama’s ascendance, no other politician has had such a deep influence on the direction of the Democratic Party—except perhaps the sitting president.

And yet, as Sanders takes steps toward a second run for the Democratic nomination, many think that he has lost his political momentum. “I don’t see a lot of lasting energy for Bernie,” Markos Moulitsas, the founder and publisher of Daily Kos, told The Boston Globe. “It’s different from last time when he was the alternative to an unfortunately flawed front-runner, and there were just two of them. Right now, the mantle of ‘progressive’ can be carried by any number of candidates and potential candidates.”

Sanders, this line of thinking goes, is “a victim of his own success”: Yes, he moved the Democratic Party leftward, but he’s been neutered by younger, more broadly appealing candidates who are aping the ideas he popularized. So Sanders allegedly can’t count on his army of supporters to turn out in droves a second time, or even necessarily his staff. “The reluctance of former aides to embrace another campaign reflects what’s expected to be a sprawling field of Democrats stampeding left—unlike the binary Hillary or Bernie choice during most of the Democratic primary two years ago,” Politico reported in December.

Yes, Sanders will face more challenges in 2020 than he did in 2016, when the Democratic Party cleared the lane for Clinton, leaving him as the only true alternative. When the primary begins in earnest later this year, there may be as many as three dozen challengers, many (perhaps most) of whom will support Sanders’s key promise, Medicare for All. But the argument that Sanders has fundamentally lost his political appeal understates the differences between him and the emerging Democratic field.

No one questions that Sanders demolished the conventional wisdom in 2016. He was an undecorated independent senator from an extremely liberal state who only identified as a Democrat to run for president, and moreover described himself as a democratic socialist. Yet he forced the prematurely anointed Clinton, around whom the entire party establishment had coalesced years prior, to campaign like hell until the very end.

Nonetheless, for weeks now, outlets have been doubting the viability of a second Sanders bid for president. “Instead of expanding his nucleus of support, the fashion of most repeat candidates,” Jonathan Martin and Sydney Ember wrote in The New York Times, “the Vermont senator is struggling to retain even what he garnered two years ago, when he was far less of a political star than he is today.” By way of evidence, the article noted that some of Sanders’s supporters in Congress “won’t commit to backing him if he runs for president again—and two may join the 2020 race themselves. A handful of former aides might work for other candidates. And Bernie Sanders’s initial standing in Iowa polls is well below the 49.6 percent he captured in nearly defeating Hillary Clinton there in 2016.”

New York magazine’s Ed Kilgore gave several reasons Sanders “has lost his 2016 mojo,” including: his support was inflated by a thin field and resistance to a Clinton coronation; his policy positions have been co-opted by other Democrats who aspire to the presidency; he’s old; he’s a white man. “If Bernie Sanders has to fight to hold onto the mantle of progressive leadership, his time has surely past,” Kilgore wrote.

And on Monday, The Boston Globe noted Sanders’s declining support and waffling from many of his 2016 backers. “I’m torn ... because I was in the midst of the campaign with Bernie, but I think the people who look at that campaign need to understand the context is different,” Jonathan Tsini, author of The Essential Bernie Sanders and His Vision for America told the Globe. Other 2016 backers have begged Sanders to back off, for reasons ranging from his age to the need for new blood to his importance in leading a democratic socialist movement.

It’s undoubtedly true that the 2020 field will be much more crowded, especially on the left wing. When his long shot campaign began in 2015, Sanders was on an island, policy-wise, advocating for socialized medicine, a retreat from imperialism, and an activist response to economic problems. Over the last two years, the policies he advocated have become widely popular with Democrats and even been embraced by a number of party leaders, including several 2020 contenders.

A 2020 Sanders campaign, then, theoretically would lack both the novelty of his surprise showing in 2016 and the distinctiveness of his positions within the Democratic field. There will be other formidable challengers representing the left, like Elizabeth Warren, as well as a number of more establishment candidates, like Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand, who support policies Sanders popularized such as Medicare for All and a $15 national minimum wage.

But just because the space is more crowded doesn’t mean that Sanders doesn’t have something unique to offer. Julian Castro’s 2020 announcement speech on Saturday is a case in point. He expressed support for Medicare for All, universal pre-K, and the Paris agreement, while pledging to “not take a dime” in PAC money. But the speech itself was not exactly a Sanders-esque jeremiad against a rigged system. At times, he sounded like a second-rate motivational speaker. “Today,” he said, “we live in a world in which brainpower is the new currency of success.”

Sanders is hardly alone in having clear weaknesses as a Democratic candidate. Voters remain angry that the economy disproportionately benefits a tiny sliver of Americans; if anything, that feeling has been exacerbated by Donald Trump’s kleptocratic administration, which, with the help of a Republican Congress, redistributed $1.5 trillion in taxpayer money to corporations and the wealthy. And yet, some in the likely Democratic field—including Harris, Gillibrand, and Cory Booker—have begun courting Wall Street. This isn’t necessarily prohibitive, but it lacks the purity of Sanders’s stance.

Even Warren, the candidate who most closely resembles Sanders, has stark differences. As David Dayen argued in The New Republic in October, they represent opposite approaches to the organization of the economy: “Warren wants to organize markets to benefit workers and consumers, while Sanders wants to overhaul those markets, taking the private sector out of it.” Finally, while a new generation has taken the spotlight in recent months, rising stars like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are too young to run, meaning that what could be termed “the Sanders lane” will still be occupied by a single candidate.

Despite claims of the Sanders movement’s waffling momentum, he is still an enormously popular politician. Recent polling, both national and in Iowa, suggests that he is a frontrunner, trailing only Joe Biden. (Sanders is the second choice among Biden supporters; interestingly, despite his long history of favors for the financial industry, Biden is the second choice among Sanders supporters.) It seems possible that it’s Sanders continued popularity—and the role that some believe he played in Clinton’s defeat—that concerns figures, like Moulitsas, who are questioning his electability.

There are legitimate arguments for Sanders to sit this one out. His age is a serious concern—he’ll be 79 on inauguration day—though that’s also true of the 76-year-old Biden. Sanders benefited enormously from not being taken seriously in 2016; Clinton rarely attacked him, while the press, “Bernie Bro” takes aside, went relatively easy on him. That won’t be the case in 2020, especially with an emerging scandal from the 2016 primary: a number of former staffers have alleged lately that the campaign did not do enough to stop sexual harassment.

But it’s simply wrong that Sanders can no longer stand out in a race for the Democratic nomination. While it’s true that most of the 2020 candidates will claim the mantle of progressivism, none exemplifies it quite like he does. In his ideology as well as his personality, Sanders still occupies a singular place in American politics. Only people who are nervous about that enduring fact would argue that it’s a compelling reason for him not to seek the highest office in the land.

“Honestly I can’t believe this documentary—there’s two of ‘em.” Against the strains of “Build Me Up Buttercup,” this is how the Hulu documentary Fyre Fraud draws to a close. The disbelieving individual in question is Oren Aks of Jerry Media, the marketing firm that promoted Fyre Festival, the stupidest disaster in the annals of millennial hubris. He’s right; there are. Hulu dropped its documentary about the ill-fated festival on Monday, gazumping a Netflix documentary on the same subject slated for release on January 18. Having seen both, the winner of the contest is clear: It’s Hulu, thanks to its exclusive interviews with Billy McFarland, the dodgy entrepreneur who oversaw the whole fiasco. It also does a better job pointing out the secret villain of this story all along: the subtle menace of social media marketing.

The background is this: McFarland, who first rose to notoriety as the proprietor of Magnises, the credit card–meets–social club startup, dreamed up a celebrities-for-rent app called Fyre. The idea was that regular people could pay famous people to hang out with them. Ja Rule was on board as a partner, and the app was valued highly. McFarland and Ja Rule then tried to promote the app through a luxury music festival in the Bahamas in the spring of 2017. Due to horrendously poor organization and a cash flow problem that escalated into wire fraud, the event was a catastrophe.

High-paying customers were met with sodden mattresses in FEMA tents, rather than the opulent villas they were promised. There was zero entertainment, when performances by Blink-182 and others had been advertised. Pictures of sad cheese sandwiches in styrofoam containers soon spread across the internet, delighting those who had been wise enough not to be taken in by dreams of a “yacht brunch party” on the island of Great Exuma.

The victims in the fraud weren’t the wealthy consumers, really, but the local workers who were promised a lucrative, recurring annual event. As one caterer put it in Netflix’s Fyre, “They had every living soul on the island of Exuma who could lift a towel, working.” McFarland wrung out this island for all it was worth, then never cut the checks.

If you are here simply to know which documentary you ought to watch, then you should opt for Hulu’s Fyre Fraud because of those new interviews with McFarland. Seeing him squirm without escape is too good of an opportunity to miss. But there are other differences between the two movies. Fyre does a better job of speaking to residents of Great Exuma, while Fyre Fraud’s talking heads are better at illuminating the cultural context. Fyre shoots its talking heads straight on, à la Wild, Wild Country, which looks modern. Fyre Fraud has them look at an interviewer off-camera, which looks dated.

Both films aptly excavate the financial crimes that McFarland committed, and both name and shame the naïve mega-rich investors—like Carola Jain, wife of Credit Suisse juggernaut Bob—who poured their cash into his fraudulent bucket. But the Netflix version goes deepest into McFarland’s criminal activities. There are details in this film that do not make it into Hulu’s, such as an unnamed person at the top of Fyre who was extorting Billy for cash.

Fyre Fraud ultimately surpasses Fyre because, in addition to having access to the man at the center of it all, it is better at drawing out the social forces that facilitated McFarland’s crimes. By foregrounding shallow Instagram influencers and the employees of Jerry Media—an agency that sprang from a cheap-gag Instagram account called @fuckjerry to helm the multi-million-dollar marketing campaign for Fyre Festival—Fyre Fraud directors Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason show that this debacle could, and probably will, happen again.

To what extent does Oren Aks, for example, bear responsibility for this disaster?McFarland was the huckster in the middle, of course. But nobody would have ever bought tickets to the event if his press people hadn’t presented such a false image of the product for sale. Every ticket to Fyre Festival was sold off the back of a single advertisement, featuring supermodels cavorting in the Bahamas, plus the social media placement that spread that advertisement across the world.

Before even airing the advertisement, Fyre Festival paid a huge quantity of social media influencers to tease the event by posting orange squares to their Instagram accounts. Abjectly thirsty Instagram fans slavered over the mysterious squares, wondering what the popular kids knew that they didn’t.

Once the ad of Bella Hadid writhing in a bikini on a boat hit the internet, the deal was done. And nothing—not the blow to the Great Exuma economy, not the financial crimes that McFarland committed—would have happened to the extent it did if that Instagram bubble hadn’t inflated. McFarland is a villain, of course; both documentaries demonstrate him to be a compulsive liar and a man addicted to defrauding other people. But the insecurity and “fear of missing out” he preyed upon in his consumers? He didn’t create that.

Whether we should blame that insecurity on ourselves, Instagram’s executives, social media marketing agencies, or professional “influencers” is one of the defining business ethics questions of our time. Influencer marketing extorts customers in the tradition of print advertising, of course—it shows them something they covet, so they’ll buy it. But the added element of “real lives” in marketing has plunged the industry to a new low. The practice of selling a product has come all the way down to the level of kindergarten, where the playground queen withholds and grants her attention according to an economy that determines human worth.

This is not a world I want to live in, but ever increasingly it is the one we have. It is much too convenient to blame Billy McFarland and Ja Rule for the Fyre Festival debacle. One moment in Netflix’s Fyre stands out as an emblem of the whole affair. The Fyre staff are wasted on the beach, directing their commercial in an ad hoc fashion. Ja Rule commands the model Chanel Iman to get into the water (it is nighttime), and she demurs. He yells, “Get in the fucking water, Chanel.” The scene is a juvenile fantasy of men acting like babies, treating women like toys, and knowing that at the end there will be the gigantic payoff of other men envying them online. Envy is something that exists in our hearts, not in the minds of charlatans: We have to look there for the answers.

No comments :

Post a Comment