When an academic makes a research breakthrough, two things can happen in the public consciousness: nothing, or something. It’s hard to know which is worse. Let’s say you’re a physicist who discovers a particle that isn’t affected by gravity. If nobody outside the physics world cares about your discovery, you sigh, shake your head, get back to the lab. If your story does hit the newspapers, on the other hand, you’ll have to adjust to a different kind of outrage: Your scrupulous research will be repurposed into some bad headline (“GRAVITY DISPROVEN”) designed to yank eyeballs, extract clicks, and generally trample over your precious academic principles.

Last week, the second thing happened. In a new article for Science Advances, Anita Radini, an archaeologist at Britain’s University of York, published evidence showing the presence of lapis lazuli—an ancient, rare, lovely blue stone pigment—on the teeth of a medieval German nun. The nun’s skeleton, named “B78,” dates from the 11th or early 12th century and was found in an unmarked grave in the German town of Dalheim. By working with tartar experts, microscopists, and medieval historians, Radini was able to conclude that this woman must have been a painter or scribe (or both) who illuminated manuscripts.

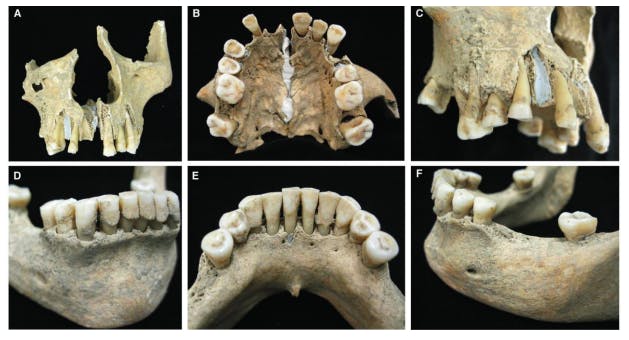

Images of B78’s teeth. Christina Warinner, Institute for Evolutionary Medicine, University of Zürich.

Images of B78’s teeth. Christina Warinner, Institute for Evolutionary Medicine, University of Zürich.She must also have been a very good one, since lapis lazuli was an extremely expensive pigment only mined in Afghanistan. It was reserved for the hands of high-end professionals. The pigment probably got into her mouth directly from the paintbrush, over the course of many years of work.

The story is delightful, all by itself. There’s an element of chance to the findings—nobody was looking for lapis lazuli on these teeth—which lends them the charm of serendipity. The confluence of beautiful medieval art and chemistry has a poetry all of its own.

But it was not quite enough for the media. Several reporters ran with the angle that this evidence countered a longstanding assumption that manuscripts were only ever painted by men. “And so these embedded blue particles in her teeth illuminate a forgotten history of medieval manuscripts,” Sarah Zhang wrote at The Atlantic. “Not just monks made them.” In The New York Times, reporter Steph Yin bolstered that narrative with this quote from the medievalist Alison Beach, who is listed as one of the paper’s co-authors:

The finding upends the conventional assumption that medieval European women were not much involved in producing religious texts. “Picture someone copying a medieval book—if you picture anything, you’re going to picture a monk, not a nun,” said Alison Beach, a historian at Ohio State University, and an author on the study.

But any medievalist worth her salt already knows that women made manuscripts, too. Beach here is referring to a stereotype, not to a lack of awareness—she’s published work for decades proving the existence of female scribes in this particular historical era. (Look up her 2000 paper “Claustration and Collaboration between the Sexes in the Twelfth-Century Scriptorium,” if you’re curious.)

The Times didn’t misrepresent Beach’s words, exactly. It mined them for the most relatable tidbit, the most pertinent comment. But medieval historians can be quite a shirty bunch, and a brouhaha over the quotation erupted on social media.

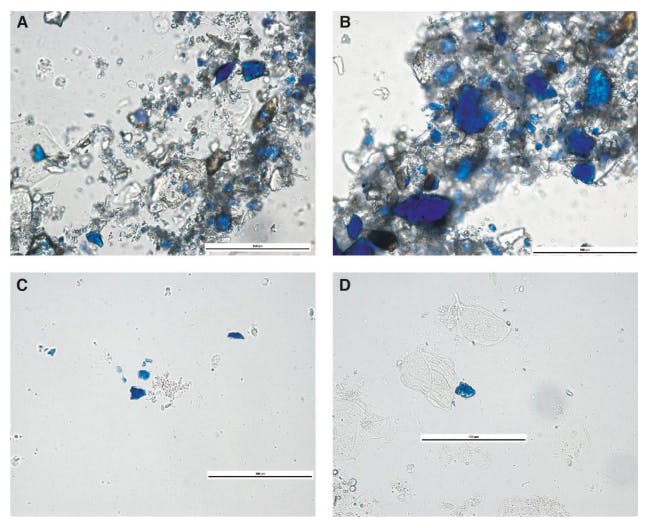

Microscope images of lapis lazuli particles that made their way into a subject’s mouth during an experiment.A. Radini.

Microscope images of lapis lazuli particles that made their way into a subject’s mouth during an experiment.A. Radini.“I share in excitement about recent lapis lazuli discovery,” Elizabeth Lehfeldt, professor of history at Cleveland State University, tweeted. “But here’s the thing: it *adds* to the existing scholarship by @AlisonIBeach and others. We haven’t ‘discovered’ that medieval women were artists. We already knew that.” Beach herself tweeted, “Amazing the degree to which [reporters] chop up what you say and reframe without ur caveats and explanations!”

Complicated arguments followed about epistemological hierarchies and rhetoric and medieval scriptoria. But the central critique was that this splashy announcement, tethered to some surprising German teeth, ended up obscuring, rather than illuminating, the long and lonely labors of medievalists.

I’ve written elsewhere about what happens in their little corner of the internet. The field contains a lot of intriguing mysteries, which leads to a lot of amateur speculation. For example, there are plenty of Redditors and the like who enjoy debating the identity of the unknown author of the Voynich Manuscript. Every now and again, some theorist will come up with a new idea; then, swift as can be, some professional medievalist will point out the glaring flaws in their evidence.

Inevitably, discussion will ensue about the sad marginalization of medieval studies in the contemporary humanities, and the way “medieval” is still bandied around as some kind of marker of barbarism. But the case of the nun with the blue teeth is a much more interesting controversy, because it stems from many-layered assumptions—both historical and contemporary—around gender and labor. Journalists assumed that women didn’t make manuscripts. Moreover, they assumed that this assumption was widespread even in the field of medieval studies.

Beach has been generous about the Times piece, and all those excited by nun-teeth-gate; “rather than lament that people didn’t know about my work of 25 years,” she tweeted, “I am celebrating that this [evidence] got the attention it did.” Furthermore, Beach tweeted, “knowing that women copied books and [...] shifting the a priori assumptions of our own broader academic field are two different matters.” Just because informed academic circles were aware that this German nun wasn’t an outlier, doesn’t mean that prejudice against women’s roles in history doesn’t perpetuate itself, even within academia. “I still struggle to get some colleagues to consider female production and provenance,” Beach wrote.

And so the surprising story of some blue-flecked teeth has taken on an odd new life. Despite the apparent neutrality of the paper’s information—chemical analysis reveals presence of blue stone in medieval tartar—its contents instantly became a battleground. The German nun herself seemed to fade away, ceding importance to the reporters and chemists and medievalists and other medievalists who all claim the revelation to be their own, or to be theirs to interpret correctly.

Like the grubby old tooth itself, which under the microscope turned out to be the bearer of brilliant and complicated information, the debacle of the nun’s teeth shows us that all knowledge remains negotiable, contested. Among many, the chief lesson of the nun’s teeth must be that women and their work still matter, a lot, to people today. Archaeology has restored one woman’s resumé. It’s a little late, of course, but better than never.

In 2009, Piraye Yurttas Beim, a molecular biologist from Texas, started pitching investors on her vision for a new kind of women’s health company. The startup she had founded, Celmatix, would bring the power of big data and cutting-edge genetic testing to bear on a problem that had long resisted comprehensive understanding and reliable treatment: infertility. Beim was 30 years old, and she had recently completed her Ph.D. at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. She found herself surrounded by women in their thirties who, like her, were highly educated, successful in their careers, and childless. She kept hearing stories from friends and colleagues who failed multiple rounds of fertility treatment, and they didn’t know why. “Very few of my friends just got pregnant with no issues or miscarriages. Most of them had harder paths than they thought they were going to,” Beim told me. “The universal feeling was, ‘Why didn’t anyone tell us this was a possibility?’”

It was a bad time to go searching for startup capital. The U.S. economy was still reeling from the global financial collapse, and investors showed little enthusiasm for backing a women’s health company, especially one with interests as esoteric as genetic testing for infertility. “What I was hearing from the investment community was, ‘This is so niche. We go after things like diabetes,’” Beim recalled. Venture capitalists couldn’t get excited about a business that catered only to women. Being a female founder trying to make inroads in the notoriously male-dominated tech world likely didn’t help; just 2 percent of venture capital dollars go to female-led startups. “The math suggests that maybe the fact that I was a woman may have made it a bit harder,” Beim told me. “I don’t know. I’ve never fund-raised as a male.”

Ten years later, however, the cultural and economic landscape has shifted. The conversations Beim was having with her friends around the dinner table about balancing career and family have pushed forcefully into the mainstream. Today, more women are working and pursuing higher education than ever before, and they are waiting longer to have children—if they decide to have children at all. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the birth rate in the United States has fallen to its lowest level in 30 years, and the number of American women having children in their thirties is now greater than the number of women having children in their twenties.

As a result, women’s infertility can no longer be considered “niche.” Today, one in six couples in the United States has trouble conceiving, and 7 million women seek infertility services every year. Egg-freezing, once an experimental procedure designed for women with serious medical conditions like cancer, has become a major industry worth $1.9 billion. Despite the demand for fertility treatment, however, women still lack good, detailed information about their reproductive health, and the treatment options available to them are expensive and often unreliable. Although medicine has made great strides over the past 20 years toward helping couples have children, the chance of having a baby through in-vitro fertilization (IVF) remains low: just over 20 percent for women under age 35, according to the CDC, and just 4 percent for women over 40. Twenty percent of couples who struggle with infertility never learn the cause.

In response to these cultural changes, Silicon Valley, once again flush with cash, has set its sights on women’s reproductive and sexual health. In recent years, “femtech” companies have brought to market a wide array of products and services that are advertised as helping women along the path to self-determination

and healthy, sustainable lifestyles. Women can now purchase menstrual cycle tracking apps and gadgets (“Fitbit for your period”); organic, chemical-free, reusable, and home-delivered feminine hygiene products; at-home fertility tests; urinary tract infection-preventing pink-lemonade powder; apps that deliver birth control and antibiotics (for the UTIs that can’t be prevented); and much more. The research and consulting firm Frost & Sullivan recently predicted that the femtech market will be worth $50 billion by 2025.

A common thread among these companies is agency: giving women an opportunity to participate in a fundamental, and at times mysterious, biological function. Ida Tin, the founder of Clue, one of the most popular period-tracking apps on the market, touts her product’s ability to help women “discover how to live a full and healthy life,” as she writes on her company’s web site: “Every single data point you enter and share empowers you to be in charge of your health.” Modern Fertility, which offers a hormone test that allows women to estimate their egg reserves, advertises itself as a reassuring answer to a question that causes many women an enormous amount of stress: Will they be able to have children later if they wait? “Whether you’re years away from kids or thinking of trying soon, we’ll guide you through your fertility hormones now so you have options later,” Modern Fertility says on its web site.

Celmatix similarly offers women “peace of mind,” “clarity,” and the ability to “be proactive” when it comes to their reproductive decisions. It’s a message that has resonated with investors and made Celmatix a leader in the femtech industry. In 2016, Fortune named Beim one of the 15 entrepreneurs disrupting their industries. In 2017, Fast Company deemed it one of the most innovative companies of the year. And in 2018, Business Insider placed it on its list of startups that Silicon Valley venture capitalists predicted would “boom” that year. Overall, Celmatix has raised $72 million in funding.

It’s possible to view the whole notion of femtech as little more than a modern gloss on the health and beauty industry, applying a veneer of feminism and technology to age-old appeals to women’s anxieties and insecurities. (Example: Fur, a line of pubic-hair grooming aids.) With her scientific background, however, Beim believes she can truly help women better understand what is going on with their bodies—and maybe even help them have children. “We aren’t trying to create an existing model, like an Uber for X,” Beim told Fortune. “We have built something entirely new.”

The idea for Celmatix came to Beim soon after she had completed her Ph.D., as she was finishing the first year of a postdoctoral fellowship at Cambridge in 2009. She was living in a small apartment under the eaves of a building that overlooked the river Cam, and she rode her bike each morning to the Gurdon Institute, a research facility specializing in developmental and cancer biology. The decoding of the human genome in the early 2000s sparked incredible advances in cancer diagnosis and treatment; doctors were able to analyze tumors on a molecular and genetic level and create personalized treatment plans for their patients, offering more effective remedies with fewer side effects. Beim had spent her years at Weill Cornell studying the connections between genetics and cancer, trying to figure out why a particular cancer drug was lifesaving for certain patients but useless, or worse, for others. “I was really on the front lines of the precision medicine revolution in oncology,” Beim said.

Beim wondered how these scientific advances were being used to treat infertility, but to her surprise no one was studying it. She feared it would be decades before women would have the same kinds of detailed diagnoses cancer patients now receive. “There’s no reason why we should approach women’s health two decades into the post-genomic era the same way that we did in the pre-genomic era,” she told me. So she decided to shift her focus from cancer research to women’s reproductive health. “I had this ‘Aha’ moment where I realized, this is not happening in this field,” Beim said. “This is my calling.”

Beim kept hearing from women who had failed multiple rounds of fertility treatment and didn’t know why. “The universal feeling was, ‘Why didn’t anyone tell us this was a possibility?’”

Beim dropped out of her postdoc at Cambridge, moved back to New York, and spent the next several months sleeping on friends’ couches while she launched Celmatix. She traveled light, whittling her belongings down to what could fit into a single suitcase.

In order to build its genetic test, Celmatix had to document the known connections between fertility and genetics. There is little information about how various aspects of women’s health—medical history, family history, lifestyle choices—contribute to or correlate with fertility, so Beim set out to build a data set from scratch. She hired scientists and researchers to scour medical journals for relevant information, and she partnered with fertility clinics around the country to combine their patient information into a single database. Until that point, the information available to fertility doctors was limited to the data from their individual clinics, as well as their anecdotal experience. By combining information from multiple clinics, Beim hoped to be able to calculate more accurately whether, when, and how a couple would get pregnant. Celmatix’s data set is now the largest database about reproductive health in the world.

In 2015, the company released its first product, Polaris, custom software that allows fertility clinics to compare a couple’s health information with the data Celmatix had collected and develop an appropriate treatment plan. Polaris can forecast how likely a couple is to get pregnant using different treatment methods—intrauterine insemination versus in-vitro fertilization, for example. It can assess the probability of twins or triplets. And it can calculate the probability of having a child when couples repeat treatments or move on to new ones. In 2018, Celmatix also launched MyFertility Compass, a free online tool that offers couples similar information.

Not only can this analysis help fertility doctors pursue more effective treatments, it can also help couples plan financially. If a couple has a better chance of conceiving after one round of IVF than three rounds of IUI, for example, Celmatix might suggest that a couple try IVF sooner, because doing so could save money or allow for more rounds of treatment. Alan Copperman, the medical director of Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York, one of the top fertility clinics in the country, uses Polaris to help couples set expectations. “There’s so much anxiety that goes along with fertility treatment,” Copperman said. It can be grueling, with high physical, emotional, and financial costs. With Polaris, you “can’t always fix it, but you can help them see what their journey is going to look like or what it’s going to take to achieve success.”

Right now, Celmatix’s data only addresses fertility, but the company has a partnership with the genetic testing firm 23andMe that gives Celmatix access to a cache of data about other elements of women’s health as well. Beim told me she hopes to eventually help women navigate not just fertility, but their lifelong health. “From the first decision she’s making about what contraceptive should I use, or how do I manage my endometriosis, all the way out to the menopause transition,” she said. Beim has big ambitions. “This is the beginning.”

At the same time that Beim was launching her business, she was also reckoning with her own family planning. Not long after she founded Celmatix, she went to a friend’s dinner party. There she met a venture capitalist named Nicholas Beim, who, among other projects, was supporting entrepreneurs in Turkey, where Piraye was born. Three months later, she joined him on a business trip there; two months after that, they were engaged. Within eleven months of meeting, they were married.

Beim was 32 at the time, and just as they had approached their relationship with alacrity, she and Nicholas knew they wanted to start a family right away. Shortly after their honeymoon, Beim found out she was pregnant. The couple happily shared the news with family and close friends. Their early enthusiasm turned to grief, however, when the pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. As a scientist working in women’s health, Beim was well aware that 15 to 20 percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage. Still, she was devastated.

The couple kept trying to get pregnant for another year and a half before Beim went to see a doctor. She looks back on this time as a period of avoidance that she now wishes she could take back. “Not knowing doesn’t make it change or go away,” she told me. A hormone test revealed that she had diminished ovarian reserve—a condition that affects between 10 and 30 percent of women who experience infertility. Women with diminished ovarian reserve have fewer eggs, and it’s harder for them to get pregnant, either naturally or with IVF.

Beim sought a second opinion. That doctor diagnosed her with endometriosis, a painful disease that can also affect a woman’s ability to have children; about 40 percent of women with endometriosis find it difficult to get and stay pregnant. Beim’s doctor, however, advised her to try to conceive naturally for six more months before investing in IVF. Beim researched natural ways to boost her fertility and made changes to her diet. She was pregnant with her first son within a month.

Because Beim knew her egg reserves were low, she and her husband decided to expand their family as quickly as possible. Beim gave birth two more times in the next three years. She now has two sons, ages 4 and 5, and a daughter, who is 1. Photographs of Beim from early articles about Celmatix often show her holding her round belly or nuzzling an infant. Beim has spent most of her years as CEO pregnant or breastfeeding.

Femtech companies may be little more than a modern gloss on the health and beauty industry, applying a veneer of feminism to age-old appeals to women’s fears and insecurities.

Beim cites her own miscarriage and accelerated family planning as a huge influence on Celmatix. “I had three kids in four years, in part because I understood my metrics and I understood that if I wanted to have a family, then I wasn’t going to be able to space my kids very far apart,” she said. “If I had had this information earlier in my life, there are other things that I could have mitigated. I could have lived a much healthier lifestyle. I could have started my family much earlier so I wouldn’t have had to get it all done under the gun before I fell off a fertility cliff. It worked out for me. But it could have not.”

Many tech startups are closely identified with their founders, and it certainly doesn’t hurt Celmatix to have Beim serve as the company’s face: a woman who, by closely analyzing her own health, was able to make informed decisions and overcome her fertility problems to have the family she wanted. This is the narrative that Beim is selling: In the face of uncertainty and the dreaded biological clock, Celmatix can give women valuable information, a sense of control, and a path toward motherhood.

But Beim’s story also highlights some of the contradictions that she and Celmatix embody. Celmatix aims to disprove the idea that older women can’t have healthy children or that infertility is the result of poor lifestyle choices. The “fertility cliff” that women supposedly hit when they turn 35 isn’t an insurmountable obstacle, the company suggests, but something that can be navigated on an individual basis through science and data. For some women, however, having more detailed information about their fertility doesn’t necessarily lead to feelings of empowerment; knowing more about one’s reproductive limitations can just as easily cause anxiety and grief. Neither Celmatix nor any other femtech company can avoid the fact that fertility changes as people age, for both men and women. Despite Celmatix’s assurances, the biological clock is real, and the outcomes aren’t always as positive as they were for Beim.

In 2017, after eight years of development and a lengthy approval process, Celmatix finally released its proprietary genetic test, called Fertilome. By examining 49 variants in 32 genes, the test can help identify a variety of fertility disorders, including polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, recurrent pregnancy loss, and primary ovarian insufficiency—a rare condition that occurs in approximately 1 percent of women and causes premature menopause. The test requires a simple blood or saliva sample. Women can request it through a physician for $950. Patients receive a detailed report on each of their tested genes, indicating a strong, moderate, or weak risk for a reproductive condition.

Beim was one of the first women to take the Fertilome test. The results confirmed what her doctors had suspected: She had genetic markers associated with endometriosis and primary ovarian insufficiency, as well as alterations in key genes that make it harder for her body to regulate inflammation, which affects whether an embryo will implant correctly in the uterine lining.

Fifteen months after the test launched, more than 100 doctors around the country had ordered it for their patients. One of Celmatix’s customers is a 35-year-old woman named Amie, who requested that her last name not be published to protect her privacy. A nurse at a neonatal intensive care unit in San Jose, California, Amie always knew she wanted to have children. “At least one boy and one girl,” she told me. She had never really experienced any menstrual issues until she was 29 or 30, when her period became irregular. A specialist diagnosed her with diminished ovarian reserve, one that was “more reflective of someone who might be menopausal.” No doctor was able to tell her what might be causing her condition or how to treat it.

When Amie got married in 2015, she and her partner decided to try to have children right away—“because I knew there might be some challenges,” Amie said. A year of trying came and went. Then, in 2017, she visited a fertility doctor, Aimee Eyvazzadeh, in San Ramon, California, who suggested that Amie take the Fertilome test. The results showed that Amie had a genetic variant that may decrease follicle stimulation—the cause of her low egg reserves. “There was nothing that I could have done to prevent it,” Amie said. “It gave me a lot of closure.”

It also gave her doctor new ideas for treatment. Because Amie’s ovaries don’t naturally produce mature eggs, Eyvazzadeh stimulated her ovaries with oral medications and estrogen patches. An ultrasound revealed one promising follicle. “The doctor said, ‘This is your golden egg,’” Amie told me. She got pregnant using IVF and gave birth to a baby boy in May. Her baby is already sporting a double chin and “juicy thighs,” Amie said. She said she’s enjoying every aspect of motherhood so far.

Things don’t always go so well, however. Leah Kaye, formerly a reproductive endocrinology fellow at the Center for Advanced Reproductive Services at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, told me about a patient at the clinic, Elizabeth (not her real name), who is 38 years old. She and her husband had tried intrauterine insemination three times without success before moving on to two failed rounds of IVF. At that point her doctor recommended that Elizabeth try the Fertilome test. It suggested a genetic variant in Elizabeth’s androgen receptor, which could potentially influence the function of her ovaries and uterus. In response, her doctors prescribed a course of progesterone and some additional androgen before transferring the next embryo. The procedure was a success—Elizabeth got pregnant for the first time, with twins—until it wasn’t. The pregnancy lasted just seven weeks. Elizabeth hasn’t been back to the fertility clinic since.

I remarked to Kaye how wrenching Elizabeth’s story was. Her response was gentle and open-minded. “We try to remind our patients after a setback like this that families can grow in all sorts of ways, not just the more conventional ways we learn about growing up,” she said. “When a couple wants to have a family bad enough, we always reassure them that they will make that family, in one way or another, even if it wasn’t by the exact route they initially envisioned.”

That honest acknowledgment of the limits of biological science runs counter to much of Silicon Valley’s sloganeering. For all its innovative science, Celmatix isn’t offering a cure, much less a treatment, for infertility. For now, the most Celmatix can do is give doctors a hint about what might be wrong. All the doctors I spoke with emphasized that Fertilome may help an experienced reproductive endocrinologist identify new pathways or tweaks for treatment, but no one could say for sure whether this information would lead to the birth of a healthy baby. Brian Levine, the director of CCRM New York, part of a respected chain of fertility clinics, calls Fertilome “a highly refined Ouija board.” It might point women in the direction of answers—but it might not.

There are reasons to be skeptical about the booming femtech industry. In 2014, a company called Ovascience claimed to have identified “egg precursor” cells, which it said could improve a woman’s chances of conceiving children and even pause or reverse the biological clock. In 2016, Wall Street valued the company at $1.8 billion. Yet no reputable studies have been able to support the company’s claims, and scientists have expressed doubt about whether such cells even exist; in late 2016, Ovascience’s valuation dropped to $47 million. In 2015, another company raised more than $160,000 on Kickstarter to produce the world’s first “smart” menstrual cup, outfitted with a Bluetooth sensor that would signal when the cup needed to be emptied. The campaign went viral and garnered favorable coverage from Fortune, Slate, Jezebel, and others, but more than two years after the cups were supposed to ship, the company is still doing preliminary testing.

Period-tracking apps have also caused controversy. In 2015, Glow, a popular app backed by PayPal co-founder Max Levchin, claimed that it had helped more than 150,000 couples get pregnant—a figure that experts criticized as questionable. A year later, Consumer Reports showed that Glow’s lack of security features exposed women’s data to significant privacy threats. (The company quickly moved to correct this.) A 2016 study in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine found that many popular period trackers did not accurately predict when women were most fertile. Then, in 2017, a much-hyped Swedish fertility tracking app called Natural Cycles was certified in the European Union as a contraceptive after a major study found that it was 99 percent effective at preventing pregnancy during “perfect use” and 93 percent effective during “imperfect use”—roughly on par with more established forms of birth control, like the pill. By tracking a woman’s basal temperature, the Natural Cycles app makes predictions about when a woman is most likely to be ovulating and gives either a red light or a green light on whether it is safe to have unprotected sex. Soon after, a Swedish hospital reported that 37 women who had recently sought abortions there were using Natural Cycles as their sole form of birth control. The Swedish government investigated, ultimately determining that the number of unwanted pregnancies was in line with the product’s advertised “typical use” failure rate. Despite the controversy, the Food and Drug Administration approved the app in August for use in the United States.

The shadow of Theranos also looms over health care startups. Elizabeth Holmes, Theranos’s CEO, convinced the world that she had developed the technology to perform dozens of medical tests with a single drop of blood—claims, it turns out, that were complete fabrications. Last March, the Securities and Exchange Commission charged Holmes with massive fraud for deceiving investors, and in June a federal grand jury indicted her on several counts of criminal wire fraud.

For all the startups focused on diagnosing or treating a serious health condition, there are others simply trying to ride the current feminist wave to a generous payday.

Celmatix is no Theranos: The Fertilome test passes muster in New York state, which has some of the strictest requirements in the country, and the company works closely with doctors and the academic community, exhibiting the sort of transparency that Theranos resisted. “Their leadership is outstanding, their science is incredible,” said Levine. “Piraye is brilliant. Every time I talk to her, I feel smarter.”

Beim is confident that Celmatix is helping women who are struggling to get pregnant. “The dream when we started was that babies that would not exist without us all showing up at work every day and working our tails off for a decade would exist one day—and we’re there,” she told me. “If what we’re doing makes it a little bit more likely that women can get to have as many healthy kids as they want, on their own terms, it’s worth it.” Yet many fertility experts remain concerned that we still don’t know enough about how genetics affect fertility for Celmatix’s testing to be truly useful. “The difference here is having knowledge versus the wisdom of how to apply it,” said Francisco Arredondo, a reproductive endocrinologist and owner of three fertility clinics in Texas.

Ten years after Beim founded Celmatix, the femtech industry is awash in companies whose products range from the significant to the superfluous. For all the startups focused on diagnosing or treating a serious health condition, such as infertility or endometriosis, or developing a new form of birth control, there are others that are simply trying to ride the current feminist wave to a generous payday.

All of the money currently being invested in femtech might be a sign that Silicon Valley finally considers women as individuals whose needs and desires actually matter. But it is equally likely that venture capitalists see women as little more than lucrative sources of revenue—as consumers, rather than patients—and that tugging at the fears and anxieties women have about their bodies and life choices can be a strong marketing hook.

Beim, for her part, is earnest about her desire to help women, and forthright about the limits of what she’s been able to accomplish so far. “Is Fertilome, like, ‘We planted the flag, mission accomplished?’ No,” she told me. The detailed diagnoses and treatments she hopes to offer women are still some ways away, at the very earliest.

Yet it’s clear that Silicon Valley startups need not be as mendacious as Theranos to cause harm. Even companies that cast themselves as high-minded can have a detrimental impact on society, as Facebook’s recent scandals illustrate. Tech firms have forged their identities around the idea that they can solve the world’s problems through disruption and innovation, through the amassing of personal data and the achievement of scale—promises that seem increasingly dubious as time wears on and the effects of their products on the real world are revealed. Why would products for women’s health be different?

The stakes could hardly be higher than they are with fertility. Millions of women who are delaying having children want to know if the gamble they are making—waiting for better circumstances, without knowing how their fertility will age—will pay off. “We’re talking about the most sensitive topic I can think of: your fertility and your ability to reproduce,” said Levine. Femtech companies have provided avenues for women to discuss their desires, fears, and experiences with friends and doctors, and to combat the stigma associated with infertility. That alone represents a form of empowerment. But even as fertility startups market themselves as sources of clarity and answers, the science still cannot—and may never—say with certainty when, how quickly, or if a woman will get pregnant. Given that reality, it may be challenging for Celmatix and other femtech firms to make good on their promises to women—and live up to their own ideals.

Bill Barr is no stranger to the Senate confirmation process. President Donald Trump’s nominee to be the next attorney general already went through it twice before, first to serve as deputy attorney general in 1990 and then to become attorney general from 1991 to 1993. That experience, as well as the Republican majority in the chamber, will make it somewhat easier when he faces two days of intense questioning by the Senate Judiciary Committee beginning on Tuesday.

If confirmed, Barr would take command of the Justice Department at a grim moment in modern American history. He would lead an immigration system defined by its cruelty and malice under his predecessor Jeff Sessions. He would report to a president who cares little for the rule of law or the Justice Department’s traditional independence. Most crucially, he would oversee special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the American democratic process.

It’s the duty of every attorney general to uphold the Constitution and the law, of course. Since the Watergate crisis, it’s also been the attorney general’s responsibility to stand at arm’s length from the political maneuvering of the White House. Any Justice Department nominee put forward by Trump deserves extra scrutiny, and Barr’s recent actions have called into question his good faith. He has publicly defended Trump’s dismissal of former FBI Director James Comey, and drafted an unsolicited memo last summer criticizing Mueller’s obstruction-of-justice inquiry. Barr reportedly shared the memo with one of Trump’s lawyers.

Trump has frequently told reporters that he craves an attorney general who shows personal loyalty and protects him from damaging investigations. Sessions, to his credit, was not that man. Barr’s track record suggests that he may yet be the loyalist attorney general that Trump desires. Unless Barr can give a resolute “yes” under oath to each of these five questions, the Senate should refuse to entrust him with one of the nation’s most important jobs.

Will you give Mueller all the independence he needs to complete his investigation, and protect the inquiry from interference by the White House?

The two-year Russia investigation has ensnared many of Trump’s former aides and colleagues, including former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Though Trump has frequently denied it, the evidence made public so far suggests that there was at least soft collusion between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin to sabotage Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid. Mueller may yet uncover even more.

It’s no secret that Trump wants to shut down the inquiry. He criticizes it almost daily, and reportedly tried to fire Mueller at least twice. So senators should demand a promise from Barr to protect him.

We’ve been here before. In May 1973, Richard Nixon nominated Elliot Richardson to lead the Justice Department as the Watergate crisis began to intensify. Senators quickly declared that they would not confirm Richardson unless he named a special prosecutor and gave him the independence to pursue the case to the end. Richardson named former Solicitor General Archibald Cox, pledging that he would “not countermand or interfere with the special prosecutor’s decisions or actions.” Richardson resigned six months later rather than obey Nixon’s order to fire Cox, citing his pledge to the Senate.

The Saturday Night Massacre, as it became known, irreversibly placed Nixon on the path to his eventual resignation. It also set the precedent that the Senate can demand a similar pledge under oath from future attorneys general before confirming them. If Barr believes in the rule of law, he should have no trouble giving it.

If the president directs you to open a criminal investigation into his political opponents, will you refuse?

In addition to arguing that the attorney general should protect him from politically damaging investigations, Trump has shown a desire to use the Justice Department against his opponents. He led “Lock her up!” chants during the 2016 campaign, and during a presidential debate, threatened to jail Clinton if he were elected. Earlier this year, The New York Times reported that he tried to order the Justice Department to open investigations into Clinton and Comey, though he ultimately demurred on the abuse of power.

This is the stuff of Old World dictatorships, not a mature liberal democracy. Few things could be more corrosive to free government than wielding the powers of state to criminalize political opposition. Trump may not show similar restraint in the future, especially if his own legal and political situation becomes more precarious. Barr should be willing to state under oath that he would not carry out such an order.

Will you also rebuff Trump if he directs you to violate federal law or the Constitution?

In an interview last month, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson made the casual admission that he frequently had to persuade the president not to break the law. “So often, the president would say here’s what I want to do and here’s how I want to do it,” he told CBS News’ Bob Schieffer, “and I would have to say to him, ‘Mr. President, I understand what you want to do, but you can’t do it that way. It violates the law. It violates [a] treaty.’” (Trump responded by calling Tillerson “dumb as a rock.”)

This isn’t the first sign that Trump shows little fidelity to the American rule of law or constitutional governance. He routinely castigates federal judges for ruling against his legally dubious policies or for their ethnic ancestry, and suggested last November that he would bypass the Constitution’s guarantee of birthright citizenship by executive order. Tillerson’s account only highlights the need for cabinet officials who will place their oaths to defend the Constitution above their loyalty to the president.

Will you release Mueller’s report to the public if he writes one, and give him final authority over any redactions from it?

Under Justice Department regulations, the special counsel can submit a report on his findings to the attorney general at the conclusion of his or her investigation. There are persistent rumors that Mueller is currently drafting such a report, though the special counsel’s consistent silence makes it hard to determine the trajectory or progress of his inquiry. What happens to the report from there is unclear; some have expressed fears that a hostile attorney general could suppress its findings.

The Mueller report could ultimately give a damning account of foreign collusion and criminal wrongdoing by the president and his associates during the 2016 campaign. It could also fall short of the high expectations held by Trump’s opponents. Whatever its conclusions may be, it will be a valuable record of perhaps the worst attack on the American democratic process in the nation’s history. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham told reporters on Wednesday that Barr gave him private assurances that he would “err on the side of transparency” when it came to releasing Mueller’s report. If that’s the case, he should have no problem giving the Senate a similar pledge next week.

Will you forbid federal law-enforcement officials from taking any public steps, in the 90 days leading up to the 2020 election, that could affect its outcome?

Not every misfortune that befalls American democracy comes at the hands of Donald Trump. One of the most egregious breaches of election norms in recent history came from James Comey, the former FBI director. Less than a fortnight before the election, Comey sent a letter to members of Congress announcing that the FBI had reopened the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server while serving as secretary of state. FBI agents wrapped up the investigation a few days later, having found nothing yet again that would justify criminal charges.

Comey’s letter may have changed the course of the 2016 presidential election, and of American history. FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver concluded, based on opinion polls taken before and after the letter became public, that Comey’s intervention likely cost Hillary Clinton the presidency. (Some election analysts are more skeptical.) The Justice Department currently has a policy against making any moves that could alter the outcome of an election. Barr should enthusiastically vow to uphold that rule during the 2020 election and beyond.

Senators may also find other good reasons to vote against Barr’s nomination. His track record on criminal-justice matters is especially troubling. He championed harsh and punitive policies during his last stint at the Justice Department, in the early 1990s, that strengthened mass incarceration’s grip on American life. Most experts, including many conservatives, have now embraced reforms that make it easier for prisoners to rejoin society. It’s worth probing whether Barr has had a similar change of heart.

But it should not be difficult for a public official who believes in the rule of law to answer “yes” to the five questions above. If he refuses to do so, the Senate should roundly reject his nomination.

The series of strikes shaking Damascus and its southern countryside last Friday night now appear to have been the most extensive wave of airstrikes by Israel against Iranian-linked targets in Syria since September. They also came only a day after U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s high-profile anti-Iran speech in Cairo, part of his week-long tour of the Middle East which, along with National Security Adviser John Bolton’s visit, were intended to reassure U.S. allies following President Trump’s abrupt decision to withdraw U.S. forces from Syria. Taken together, the events indicate Israel feels it can not rely on the U.S. in its efforts to counter Iran’s regional ambitions. Without either the U.S. or Russia stepping in to constrain Iran, Israel will keep striking targets in Syria, thus increasing the chances of a large-scale conflagration.

Since late 2012, Israel has carried out thousands of airstrikes in Syria, intending to disrupt the transfer of advanced weaponry from Iran to Lebanese Hezbollah through Syria, and prevent the establishment of permanent Iranian bases in the war-torn country. Following Russian intervention in the Syrian war in September 2015, Israel and Russia came to an agreement allowing Israel to continue carrying out such strikes. Under the deal hammered out between Jerusalem and Moscow, Russian servicemen stationed inside the anti-aircraft batteries Russia deploys in Syria would switch off their systems once Israel notified Russia of an impending strike, minutes in advance.

In September 2018, however, all of this came to a screeching halt when, in response to an Israeli airstrike, Syrian air defenses accidentally shot down a Russian military aircraft, killing all 15 crew members on board. Russia blamed Israel for the death of its soldiers, transferred advanced air defense batteries—the S-300 and S-400—to the Syrian military, stopped turning off Russian air defense systems, and demanded that Israel notify Russia hours in advance of every strike. Initially, Israel halted all attacks in Syria, but then began carrying out smaller strikes. Yesterday’s attack, apparently hitting four different locations, is the largest since September, signaling Israel’s insistence on continuing to counter Iran’s efforts to ferry weapons to Hezbollah.

Inconsistent policy out of Washington has complicated this situation since the beginning.Inconsistent policy out of Washington has complicated this situation since the beginning. There’s also ample reason to believe it has helped trigger Israel’s recommitment to airstrikes within the country. Since Trump’s election, Israeli officials have voiced frustration about the disparity between the Trump administration’s bellicose anti-Iran rhetoric and its conduct on the ground. While some administration officials attempted to transform the U.S.’s anti-ISIS intervention in Syria to one intended to stymie Iranian expansionism, Trump rebuffed such efforts. Instead, his sudden announcement in December of the decision to withdraw all U.S. troops from Syria dashed whatever hope remained among Israeli policy-makers that the U.S. would help counter Iranian ambitions in the region. In this context, the aggressive language toward Iran in Pompeo’s Cairo speech on Thursday, only highlights the disparity between U.S. actions and rhetoric.

Despite publicly excoriating Iran and pulling out of the nuclear accord known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Trump administration in its first two years maintained a Syria policy almost identical to that of the Obama administration—whose Middle East policy Pompeo criticized at length in his partisan Cairo speech. So the December announcement of U.S. withdrawal from Syria, understandably celebrated as a victory in Tehran, was seen as a major blow in Israel. Israeli national security depends on U.S. power projection and reputation as a reliable ally. While most international attention focused on the planned withdrawal of U.S. troops from northeastern Syria, an area under the control of the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces, Israeli officials were concerned about the withdrawal of U.S. troops from al-Tanf, on the Iraq-Jordan-Syria border triangle. The removal of U.S. forces and the Syrian Arab rebels they back in the area would significantly decrease the length of the ground line of supply Iran has invested in creating, which spans from Iran, through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon. Currently, Iran is forced to use the longer route, through Deir Ezzor, eastern Syria, to bypass U.S. troops. And at this point, it is unclear whether White House national security adviser John Bolton’s assurances to Israel, stating that U.S. forces will remain in al-Tanf, reflect the will of Trump and eventual U.S. policy.

Under these constraints and with decreasing leverage due to the U.S. withdrawal, Israel is determined to continue countering the transfer of weapons to Hezbollah and the establishment of Iranian military bases. But in its current form, that’s probably a losing battle: The hundreds of Israeli strikes since 2012 failed to prevent Hezbollah from significantly augmenting its rocket and missile arsenal. Such strikes are also ineffective in countering Iran’s influence over the Syrian Army and the local Syrian militias it backs, to say nothing of Iranian efforts to win the hearts and minds of Syrian civilians, mainly through targeted humanitarian and financial relief.

The incoherence of U.S. policy in the Middle East coupled with Trump’s isolationist instincts leave Israel on its own to face Iran’s presence beyond its northern border—not a situation likely to help those in the security world sleep at night. Tehran and Hezbollah feel emboldened after securing a victory for their ally Assad against the armed opposition while increasing their influence in the country. The withdrawal also necessarily undermines the appearance of the United States as a reliable ally in the Middle East, both to Israel and others.

Israel is left with few options. The Israeli Defense Forces will continue bombing occasional weapon transfers, while hoping those raids do not lead Iran to ship weapons directly to Lebanon by air. Jerusalem will continue engaging Russia in an effort to get the Kremlin to encourage Damascus and Iran to halt Iranian buildup in Syria. The conflict between Iranian and Israeli interests in Syria, coupled with Russia’s inability or unwillingness to serve as a mediator between them, ensure that Syria will remain an arena for this regional contest. One wrong move and the conflict currently contained in Syria could spill into Lebanon and Israel.

No comments :

Post a Comment