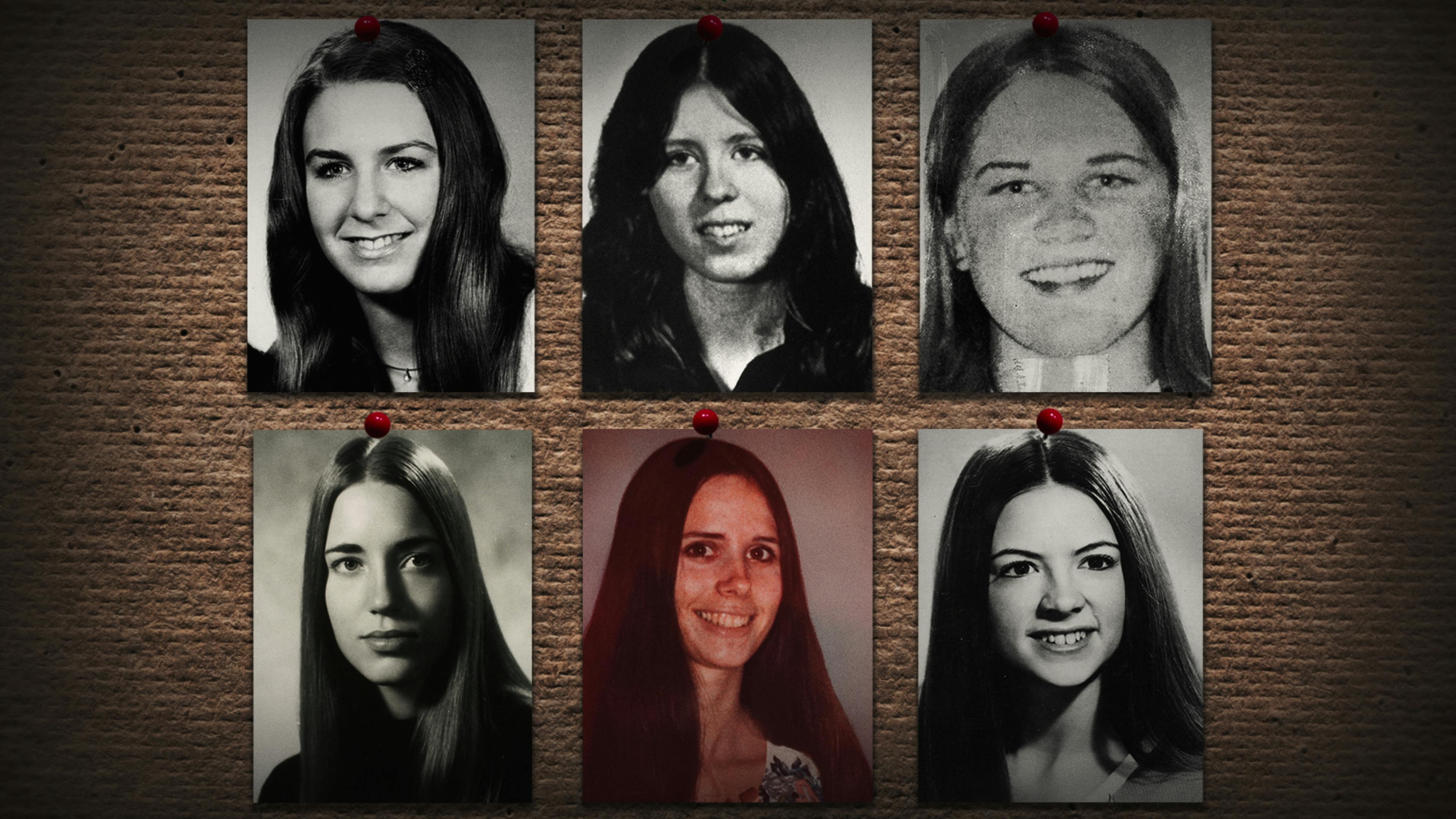

There is a rich abundance of nonfiction entertainment about Ted Bundy, America’s most notorious serial killer. In each instance, the author or television producer tells the story of Bundy’s heinous crimes, juxtaposing Bundy’s handsome face, in whatever disguise he favored that day, with the beautiful young women with long center-parted hair whom he murdered. These are the bare facts of the case, and they have been enough to generate a frisson in the American audience that has buzzed, undimmed, to the present day.

This year is the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s execution in an electric chair, and the buzz is rising to a screech. This week the biopic Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile, starring Zac Efron as Bundy, premiered at Sundance. And the latest television contribution to Bundy canon is Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, a four-part Netflix docuseries. It is based on 150 hours of audiotape belonging to journalist Stephen Michaud, who interviewed Bundy for his book, Only Living Witness: The True Story of Serial Sex Killer Ted Bundy, while Bundy was on death row in Florida. In the tapes, Bundy describes his own actions in horrible detail, and we get to listen in. Lucky us.

The show is put together chronologically, with archival footage cut between talking-head testimonials from cops, friends, and survivors. Its organizing motif is an animated reel of tape, meant to invoke the analogue origins of the show and connect it to other recent serial killer offerings set in the 1970s, like Mindhunter. Michaud’s tapes are pretty remarkable. He describes how resistant Bundy was to his queries at first, but how he then opened up like a flower once Michaud asked him to speak about himself in the third person.

As in every single piece of entertainment ever made about this killer, the show heavily emphasizes how impossible it seemed that he could have been guilty of these crimes. He seemed smart, normal, handsome, well-adjusted, everyone says. And yet here is Carol DaRonch, the extraordinary woman who in 1974 fought Bundy off even after he had her partially handcuffed inside his Volkswagen. No matter how unlikely of a killer he seemed, she is here to tell us that he hit her with a crowbar.

The show’s chief flaw lies in its sympathetic portrayal of law enforcement. Various cops describe Bundy as preternaturally intelligent, evading them at every step. In fact, he simply started out murdering women in different jurisdictions, then crossed state lines to do the same thing again. It’s true that the police at this time had no easy way to cross-reference evidence from different cop shops, but there are multiple points in the Bundy story where sheer idiocy prevented his capture.

After he murdered 21-year-old Lynda Healy in Washington, for example, investigators initially assumed that the blood in her bed was either from a nosebleed or menstruation. In his book The Riverman: Ted Bundy and The Hunt for the Green River Killer, King County detective Robert Keppel wrote of the first investigators that “[b]ecause they assumed Lynda Healy was possibly having her period at the time of her disappearance, they couldn’t figure out why anyone would kidnap her—they assumed no kidnapper would want to have sex with her.”

None of this makes it into the show. The focus is instead on Bundy himself. Netflix, to a distasteful degree, plays up the ghoulish fascination he exerts over us. In its press materials, the streaming service says he “invades our psyche in a fresh yet terrifying way.” The idea is that it’s really “our psyche” on display here. The ultimate question Bundy asks the audience is this: Would you have known?

Something about his persona is extremely disconcerting to white, middle-class Americans. His superficial charm and medium good looks were all the cover that he needed; simple disbelief prevented his identification for far too long. The “career” of Ted Bundy, which claimed 30 lives or more, is therefore a direct indictment of American society. It turns out that the kind of face we find attractive is also the kind of face that can disguise. What does that say about male beauty in the 1970s and beyond? Well, it says that we are most attracted to the average, to the indistinct, the kind of face that could belong to anybody.

There’s also the question of Bundy’s legion of female admirers, who showed up to support him during his trial. His fans professed a simple attraction to his face and comportment, but there’s no doubt that his misogynist violence fascinated a certain sector of women. Perhaps it’s the idea that women exerted a mythical, archetypal power over him. If he was powerless to resist the urge to bite Lisa Levy’s nipple almost clean off, then, the thinking goes, Lisa Levy must have really meant something to him. It’s a strange logic, but it works perfectly inside the matrix of gendered power, in which women are supposed to be empowered by passivity, ruling the domestic sphere like goddesses. It’s no coincidence that Bundy liked to invade homes and murder women in their beds.

Ted Bundy, then, turns out to be an avatar for our darkest selves. And who doesn’t want entertainment like that? I had to admit, watching the show, that in certain of Ted Bundy’s guises, he resembled a man that I would consider attractive. In other disguises, not. Looking at his different incarnations, I trained my analysis on my own desire, trying to figure out whether I believed him when he spoke; whether I found his courtroom jokes funny; whether I would have known that my coworker murdered women for pleasure.

But this kind of entertainment isn’t particularly enlightening. The experience of watching Conversations With a Killer is characterized by prurience, self-obsession, and, ultimately, a failure to hold to account the men who should have investigated these crimes properly. At its best, it reminds us that DaRonch, the crowbar survivor, was beautiful then and remains beautiful now. She puts a face to the kind of woman that Bundy’s victims could have—should have—become. I prefer to remember her face than his.

Everything that could go wrong with Britain’s imminent departure from the European Union seems to have done so. With only 59 days to go until the U.K. automatically crashes out of the bloc, British lawmakers still haven’t approved a deal with EU leaders that would avoid a cataclysmic rupture. The odds are not good. The House of Commons decisively rejected Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposal earlier this month, handing her the biggest parliamentary defeat for a British government in the country’s history. Members will vote on Tuesday on amendments to May’s “Plan B” legislation that could avoid, or guarantee, a no-deal Brexit.

As an American, following this debacle is like watching one sinking ship from the deck of another sinking ship. The Brexit vote was a foreshock of sorts, a surge of ethno-nationalist populism that preceded President Donald Trump’s election by six months. “Basically, they took back their country,” Trump told reporters when he landed in Scotland the day after the referendum. He rode a similar confluence of factors—unabashed xenophobia, the Great Recession’s unhealed wounds, a discredited generation of centrist elites—to the most powerful office in the world.

Neither Trump nor Brexit have lived up to their promises, each inflicting tremendous damage to their country’s political and social life. Trump has ripped thousands of children away from their parents, given tacit support to white supremacists, encouraged violence against political opponents, and sowed distrust of the free press, federal government, and even American democracy itself. But his harms, while acute, are ultimately treatable—many are even reversible.

Brexit is different. There are immediate damages, to be sure, in terms of economic losses. But the consequences of Britain’s departure from Europe won’t be fully known for years, and almost certainly will be more enduring than Trump’s. The nation will be diminished on the world stage and within, as younger generations are deprived of opportunities enjoyed by their parents and grandparents for decades.

It’s hard to argue that, at this moment in time, Brexit is worse for Britain than Trump is for America. But it’s also easy to see how, half a decade from now, that will be true. And if that’s so, it will be largely attributable to fundamental differences between the countries themselves.

The Founding Fathers built the American system of government with someone like Trump in mind: a corrupt demagogue who shows no interest in protecting minority rights or upholding the rule of law. Federal judges throughout the lower courts have blocked his administration’s legally dubious policies from going into effect. American voters last fall handed Democrats control of House of Representatives to act as a check on the president. Impeachment threats appear to have blocked him from shutting down the Russia investigation. The damage would have been further minimized if Congress hadn’t ceded so much of its power to the executive branch in recent decades.

Things are much different across the Atlantic. Instead of an American-style constitution, the United Kingdom relies on an unwritten body of precedents and traditions to shape its political system. In practical terms, this means Parliament reigns supreme. Though Britain’s judiciary is independent, judges can’t overturn laws passed by the legislature, like their American counterparts can. The British monarch’s executive powers are now exercised by the prime minister and members of his Cabinet, all of whom are also lawmakers themselves.

The U.S. Constitution determines what Congress can make laws about and what matters are left to the states. Parliament, on the other hand, has “sovereign and uncontrollable authority in making, confirming, enlarging, restraining, abrogating, repealing, reviving, and expounding of laws, concerning matters of all possible denominations, ecclesiastical, or temporal, civil, military, maritime, or criminal,” Lord Blackstone, Britain’s most celebrated jurist, wrote in the eighteenth century. “It can, in short, do everything that is not naturally impossible.”

Everything, that is, except forge a transitional agreement to leave the European Union. May’s Conservative Party is torn between Brexit hardliners who demand a departure from the bloc at all costs and a range of other Tory factions that want something less destructive. Last year, she called a snap general election in hopes of securing a mandate to negotiate an agreement on Britain’s behalf. Instead, her party lost seats and became dependent on support from Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to stay in power. The DUP’s influence has made it harder to reach a consensus on the Irish border, which is supposed to stay open under the Good Friday Agreement but likely will close if Britain crashes out of the EU.

Most of Britain’s other political parties favor a second referendum to halt Brexit, but they lack the votes in Parliament to make it happen. The Labour Party, the House of Commons’ official opposition, is officially silent on the question and many other Brexit-related matters. Most of Britain’s political establishment faults leader Jeremy Corbyn, a longtime Euroskeptic in a generally pro-Europe party, for not offering a viable alternative to May’s plans. His supporters counter that he’s trying to outmaneuver the Tories in preparation for the next general election. Whatever the reason for his ambiguity, the result is chaos and a likely no-deal Brexit in two months.

All of this has had a withering effect on Britons’ faith in their political and social institutions. One recent survey found that 61 percent of respondents felt their views weren’t being represented in the nation’s political debates. Neither May nor Corbyn had more than 40 percent approval in the survey. Almost 70 percent thought their politics had become angrier in recent years, while 40 percent said they feared political violence would grow. Those who voted for Britain to remain in the European Union are, somewhat understandably, less optimistic about the country’s future. But even those who support Brexit are feeling disillusioned: The survey found that 43 percent of them think the country is on the wrong track.

Americans are feeling dispirited about their futures as well. In the wake of the partial government shutdown, an NBC News poll found that 63 percent of Americans think the country is on the wrong track. Beneath those numbers, however, there are signs of reinvigoration in the nation’s political spirit. Millions of Americans have taken part in protests and demonstrations across the country since Trump took office. Newspaper and magazine subscriptions have skyrocketed amid Trump’s constant attacks on the press. The American Civil Liberties Union, which has led the legal resistance to Trump’s policies, has seen its membership quadruple since the 2016 election.

A similar revival of Britain’s political culture has yet to take place. One factor may be the lack of opportunities to change the U.K.’s fate. Trump is ultimately constrained by the transitory nature of his office. Americans will have an opportunity to remove him from office next year. Even in the unlikely event that they do not, he would still depart the White House by 2025. Brexit has no end date. It stretches out before that country like an endless sea. So while Trump only has a few years to upend American lives and livelihoods, Brexit may still be shaping British destinies for generations to come.

After months of rumors that he was weighing a presidential bid, former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz finally confirmed them on Sunday. “I love our country,” he tweeted, “and I am seriously considering running for president as a centrist independent.” Why not run as a Democrat, as many had speculated he would? That would be “disingenuous,” he told The New York Times. “When I hear people espousing free government-paid college, free government-paid health care and a free government job for everyone—on top of a $21 trillion debt—the question is, how are we paying for all this and not bankrupting the country?”

This news has stirred panic among Democrats. “If he enters the race, I will start a Starbucks boycott because I’m not giving a penny that will end up in the election coffers of a guy who will help Trump win,” tweeted Neera Tanden, the president of the Center for American Progress. Even Michael Bloomberg, himself a centrist CEO who has flirted with an independent bid in the past, warned Schultz against it. “Given the strong pull of partisanship and the realities of the electoral college system, there is no way an independent can win,” he said in a statement. “In 2020, the great likelihood is that an independent would just split the anti-Trump vote and end up re-electing the President. That’s a risk I refused to run in 2016 and we can’t afford to run it now.”

But the fears that Schultz will draw enough support from independents and liberals to result in Trump’s reelection are overblown. He has no constituency. As The Onion put it, with a rare headline that was more factual than satiric: “Howard Schultz Considering Independent Presidential Run After Finding No Initial Support Among Any Voter Groups.” Rather than discourage him from running, Democrats should welcome it—to prove once and for all that few American voters are craving a moderate “chairman emeritus” who fear-mongers over the national debt and blames both parties equally for the country’s hyper-partisanship.

Schultz’s case for running as an independent, if he decides to do so, is that both the Republican and Democratic parties are dominated by extremists and neither cares about the most important issue facing the country: the national debt, which he describes as “greatest threat domestically to the country.”

The question I think we all should be asking ourselves is: at this time in America when there's so much evidence that our political system is broken - that both parties at the extreme are not representing the silent majority of the American people - isn't there a better way? pic.twitter.com/Gy1wf1cf8F

— Howard Schultz (@HowardSchultz) January 28, 2019There is good reason to believe that the “silent majority” Schultz evokes doesn’t agree that the national debt is the “greatest threat” facing the country—and there is ample evidence that it isn’t such a threat. Voters have recoiled when presented with proposals to cut entitlements like Social Security and Medicare. A President Schultz, moreover, could expect a serious political fight if he tried to significantly cut either social or military spending, which drive the public debt. But there is also growing evidence that debt scolds like Schultz are severely overstating the current risks. “It’s becoming increasingly doubtful whether there’s any right time for fiscal austerity,” the Times’ Paul Krugman argued earlier this year. “The obsession with debt is looking foolish even at full employment.” Furthermore, the current situation is hardly dire.

Now, investors are happy to buy U.S. debt at low yields (and to buy the bonds of much more highly indebted countries like Japan), and the former chief economist of the IMF has presented detailed evidence that the debt threat is overrated ... but 3/ https://t.co/7Nh6WPmxkg

— Paul Krugman (@paulkrugman) January 26, 2019It’s not clear what else Schultz stands for. He has dismissed universal health care as too expensive and unrealistic, but otherwise has punted on the most salient political issues of the day. He has refused to address “hypothetical” questions, like whether he we would raise taxes. For now, then, his potential candidacy revolves around a single issue, and yet there’s no evidence that anti-debt voters exist in numbers that would propel Shultz to the White House, or even remotely close to it.

Democrats, notwithstanding House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s maddening devotion to pay-as-you-go rules, have long been unafraid to increase the debt to fund important social programs such as Obamacare. The Republicans have long used the national debt as a bogeyman to justify cuts to such programs, while simultaneously pushing for massive increases to the military budget and tax cuts for the rich. But their actions under Trump have given lie to their rhetoric, as they passed a $1.5 trillion cut despite being fully aware that doing so would balloon the deficit in a time of plenty. As for the public broadly, the percentage of Americans who say they worry a great deal about the national debt has been declining for years; voters increasingly are motivated by divisive issues like health care, immigration, and foreign policy.

But Schultz wouldn’t make a weak candidate simply because his core issue isn’t compelling enough. The fact is that nothing about him is compelling enough. For years now, sober pundits have made the case that someone like Schultz—a successful businessman who is fiscally conservative and socially liberal—should enter the political arena. To escape from decades of partisan gridlock, the argument goes, America needs an outsider who can cut through the Gordian knot of ideology and deliver real results.

The idea that outsiders make the best political leaders is baked into the American political consciousness. It’s why Lincoln’s supporters cast him as a log-splitting homesteader, and why George W. Bush, a trust fund kid from Connecticut, ran as a swashbuckling cowboy. But over the last three decades, particularly in the aftermath of the Republican Revolution of 1994, the notion that America needs a leader who comes from outside the two parties has been particularly resilient. Groups like No Labels, Third Way, and, most recently, WTF emerged to fill an imagined vacuum: that there exists an American political consciousness that has been obscured by partisanship, waiting to be tapped by the right candidate (which, inevitably, is a rich white man). But these groups’ center-right economic agenda—focused on the solvency of Social Security and Medicaid and lowering the National Debt—has proven enormously unpopular in recent years.

Of course, America sometimes does elect a true outsider, and there’s no better example than the current president. Trump won by deviating from orthodoxy, promising to protect entitlements like Medicare and Social Security while spewing racist paranoia about illegal immigration and urban crime. But this is not the kind of candidacy that Schultz is proposing. Quite the opposite. He will neither kill sacred cows nor pander to voters’ basest instincts, and he doesn’t have quite the same knack for social media:

does Howard Schultz have the first account to consist of nothing but ratios pic.twitter.com/NLftCj1Uv2

— Ashley Feinberg (@ashleyfeinberg) January 28, 2019Schultz contends that the Democrats will be to blame for a Trump victory in 2020 if they nominate a far-left candidate, but that is not borne out by current polling, which shows Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren with comfortable leads over the president. While there’s no polling yet on how Schultz would fare in a matchup against the president, he has pointed out that the number of Americans who identify as independents is higher than the number of those who identify as Democrats or Republicans. But as The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake wrote, “as any political scientist will quickly point out, though, ‘independent’ isn’t always truly independent, and most of these voters clearly favor one party over another.” The real number of voters without a “home base” in one of the parties? Twelve percent. And it’s by no means clear that Schultz would win many of those voters.

This is not to say Schultz lacks any constituency. He has one in America’s boardrooms and on its trading floors. He will be welcomed by some Democrats who feel alienated by the party’s growing embrace of Medicare for All and a Green New Deal. And he’s already being embraced by some of the remaining #NeverTrump Republicans: The Atlantic’s David Frum on Monday echoed Schultz’s inaccurate belief that the two parties are equally extreme, writing that “if you seriously believe that the Trump presidency presents a unique threat to American democracy, you want the safer choice, not the risky one.”

The myth that a centrist, independent CEO can bridge America’s political divide has persisted precisely because no one has seriously tried it in a generation. And no one has tried it because—as Ross Perot learned in the ’90s, and even Bloomberg realizes today—the numbers simply don’t work. That’s all the more reason to encourage a milquetoast moderate like Schultz to run. His campaign will end in ignominious failure and finally kill this myth once and for all.

What does it mean to be a man? In the United States, that’s a debate recently stoked by a Gillette ad about harmful masculine norms, as well as the American Psychological Association’s new guidelines to help therapists work with men and boys in a culture that tells them to hide their emotions and pain. But though it’s a question some dismiss as philosophical rather than practical, or a badge of “political correctness” culture, research in the past several years has suggested it’s also a question with profound implications for international relations: Put simply, how men define their roles—and whether they’re able to live up to them—can have real consequences for national security. And in some of the theaters in which the United States has tested its military prowess in the past two decades, goals may be foiled not by the mechanics of fourth-generation warfare, but what may seem a much more pedestrian issue: gender.

On January 29, the gender equality NGO Promundo released a new report showing that younger men in Afghanistan are less likely than their fathers to support gender equality, and that both women and men still define men’s roles in traditional terms—as the breadwinners and protectors of their families. The report came a day after the announcement Tuesday that U.S. and Taliban representatives had tentatively agreed to a peace framework.

Two-thirds of the men Promundo surveyed agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “women in Afghanistan have too many rights.” Younger men “associate the dilution of their culture with the spread of women’s rights and gender equality ideals,” said Sayed Idrees Hashimi, a Promundo report co-author and project manager at the Opinion Research Center of Afghanistan. And these findings, in turn, have troubling implications for security.

In Afghanistan, “real men” can be narrowly defined by their ability to provide for and protect their families. For many men, living up to that socially sanctioned definition amidst inexorable physical and economic insecurity is impossible: They don’t have the money to pay a bride dowry, can’t find a job, or they cannot protect their family from extremist violence or insurgencies. “If you’re a 17, 18, or 20-year-old man in Afghanistan right now, it’s a crippling identity moment for you,” explained Brian Heilman, one of the study authors and a senior research officer at Promundo. “You feel entitled to certain elements of ‘manhood’ that you can’t actually achieve in your social environment.” Often insecure and humiliated, these men can seek power from another source—the subordination of women, and often, from extremist organizations. “Gender bias and violent extremism are two sides of the same coin,” one Afghan man who worked as a U.S. government advisor for its Promote project, designed to empower Afghan women through training and by connecting them with educational and economic opportunities, told me.

“Gender bias and violent extremism are two sides of the same coin.”The Promundo research, which included a nationally representative household survey of 1,000 male and 1,000 female participants, focus group discussions with both men and women, as well as other interviews with men, complements other findings that Afghani gender norms, which many thought the fall of the Taliban would improve, have resisted change: A 2016 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit ( AREU) study showed Afghan men across generations believed men to be superior to women when it came to leadership qualities and levels of education and thought that men held the primary responsibility for the security of their families. More than half of young and more mature men thought wife-beating was acceptable. “Our talks and discussions about women’s rights are all as slogans but nothing in action,” one AREU focus group participant told researchers. “Here, if a stranger bothers my wife or sister as he stares at them on their way home, I cannot tolerate that; I would have to kill him, or else I am not called a man in my community… .”

In recent years, political science research has increasingly suggested a correlation between gender equality and a number of indicators of stability and prosperity: GDP per capita, growth rates, and low corruption. Political scientist Mary Caprioli, to cite just one example, has found that increased political, economic, and social gender equality makes states less likely to resort to military options in international conflicts and crises, and less likely to experience civil conflict. There’s also more specific evidence that regressive gender norms and expectations around masculinity play into terrorist recruitment: Nearly all of the former jihadi fighters interviewed in a 2015 Mercy Corps study cited a common justification for their decision to travel to Jordan and Syria to fight—protecting Sunni women and children. “Those men who went to fight, those are real men,” one young man in Ma’an told researchers.

A vendor waits for customers at a livestock market. (Noorullah Shirzada/AFP/Getty Images)

A vendor waits for customers at a livestock market. (Noorullah Shirzada/AFP/Getty Images)Some researchers have found that young men have more open and flexible attitudes about gender equality and masculinity until they reach puberty. In Afghanistan around that age, young men “begin to understand that they are never going to be accepted unless they marry and become head of a household,” Texas A&M University Professor Valerie Hudson told me. “That means they will have to come up with a bride price, which may be the equivalent of several years’ income, in addition to the cost of the wedding itself, which may involve up to 1000 guests.” Hudson’s research suggests that bride price “is a catalyst for conflict and instability”; rising prices make it harder for men who are un- or underemployed to come up with the money to pay for a bride, and more likely that they’ll turn to an extremist group that promises them either money or brides in exchange for service. Unraveling “the web of incentives and disincentives that men are given in Afghan culture,” she said, is key to understanding the patterns behind instability and extremist recruitment in the region.

Despite the relevance of gender inequality for U.S. security policy and strategy in Afghanistan, prioritizing gender norms in the military’s strategy to stabilize the area isn’t as simple as it might seem. Masculinity, anywhere, is a difficult subject. “We’ve floated talking about masculinity in the military,” one female naval commander told me. “It doesn’t go over very well. People get defensive pretty much immediately, and make it personal and visceral. It’s part of their identity.” That makes it difficult, she said, to address strategic blindspots and approach problems like violent extremism or conflict reconstruction holistically: “If we aren’t having those conversations, especially when you’re talking about dealing with male-dominated organizations, like militaries, police sectors and government, we open ourselves up to missing things,” she said. “In the countering violent extremism fight, what it means to be a man is a lot of times directly related to women. When terrorists use women and rape as a weapon of war, there is a reverberation and impact on men in society—the men who weren’t able to protect those women, and who have to resort to violence to feel like real men. That needs to be explored to really understand the problem and begin to address solutions to the instability.”

Some women, too, hesitate to integrate discussions of masculinity into U.S. foreign policy and programming, fearing it could overshadow or detract from the conversation about the needs and experiences of women and girls. “There’s a philosophical tension there,” said Jamille Bigio, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who previously worked on the White House National Security Council staff. Even in countries that are progressive when it comes to feminist foreign policy, like Canada and Sweden, the idea has been to talk more about women and girls’ needs, rather than “feminist principles, which are different. Integrating feminist principles would start a different conversation about gender norms and gender roles,” one that would systematically include men, she told me.

And in the end, challenging gender norms, and getting the buy-in necessary to shift them a bit, is not easy. Gender equality and security at the national level starts in the household—with egalitarian partnerships. But men benefit from household inequality—at least in the short-term. Spending less time on household labor frees them up to access more economic, social, and political opportunities, begetting more power and privilege outside of the home. (At the same time, they lose out in the long term on the benefits of sharing equal parenting responsibilities, for instance, and in living in a society that’s more stable, secure and productive.) And women participate in gender-policing, too. Belquis Ahmadi, a pioneer of masculinity research in Afghanistan who works at the United States Institute of Peace, told me that some Afghan women viciously ridicule men in their household who attempt to help with domestic work or who act more sensitively towards their wives. “In some parts of Afghanistan, a man who helps with the chores is called Zancho—which means a man with female characteristics,” Ahmadi said. “That’s considered the worst thing you can call a man.”

So how to fix the problem? Shifting deep-seated gender norms as part of a national security strategy first requires acknowledging that they’re linked—that gender inequality isn’t something that can be tackled after security concerns are dealt with. The two need to be approached in tandem.

As a first step, Hudson recommends working with and through religious leaders, who are traditionally the ones that enforce and encourage certain gender norms. “Westerners have a tendency to characterize religious individuals as being somehow stupid,” closing off options, she said. “If you approach them in the right way, you can make some progress.”

Policymakers must also learn from past missteps, Ahmadi suggested. After the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in late 2001, the international community, including the U.S., poured money into women’s rights programs. Their focus was to train women on what their rights were. Not long afterwards, the number of women attempting and committing self-immolation began rising in Herat.

“That’s because women knew what their rights were, but when they were demanding those rights from family members as well as in society, men did not understand those things,” Ahmadi explained. “There was backlash, domestic violence, and an increase of physical abuse. Women were desperate and there was no mechanism to protect them.”

There are some encouraging signs, Promundo study author Heilman noted: the “courageous” voices of men in the study “who speak out against restrictive masculinities and family violence,” or the women who, despite tremendous obstacles, are still taking on more leadership roles in government and the community. On December 31, 2018, 33-year-old Adela Raz, for example, was appointed Afghanistan’s first female permanent representative to the United Nations.

“Change should come from within,” Ahmadi told me. “Afghans have been challenging this way of life for many years now. It takes time. It has to be organic.” The task for the United States and other allies is to do everything they can to support and encourage that internal transformation.

No comments :

Post a Comment