By the time Jordi Cuixart and Jordi Sànchez go on trial on February 12 they will have been in jail nearly 500 days. The grassroots organizers for Catalonian independence will be tried by Spain’s Supreme Court on charges of rebellion and sedition, alongside 10 other defendants, including former Catalan vice-president Oriol Junqueras, several of his cabinet colleagues, and former Catalan parliamentary speaker Carme Forcadell. All are accused of defying the Spanish state in the fall of 2017 by mobilizing two million Catalans to vote in an unlawful referendum on secession from Spain which led to a unilateral declaration of independence by the region’s parliament.

Nine of those on trial face the sedition and rebellion charges, among the most serious crimes in the penal code. If found guilty, Junqueras could face a jail term of 25 years while Cuixart and Sànchez could receive sentences of up to 17 years.

For Spain’s judiciary and for many unionist Spaniards, this trial is the logical response to a rogue region’s outlaw actions—the restoration of law and order following a chaotic bid for independence. On Sunday, tens of thousands of people demonstrated in Madrid against Catalan independence, waving Spanish flags as they demanded a tougher stance on the issue from the Socialist government. For secessionist Catalans, however, the trial is a deeply unjust bit of political theater.

The only thing both sides can agree on is that this will be the most highly awaited and politically fraught legal process modern Spain has witnessed.

In mid-January, the pro-independence grassroots organization, Òmnium Cultural, announced an international campaign to discredit the upcoming trial. The media offensive, titled “Democracy in the dock,” (Juicio a la Democracia) advances the idea that the Spanish judiciary is deeply flawed, part of a state with flimsy democratic credentials.

“We should be bringing charges against the Spanish state because of this trial,” Catalan president Quim Torra said in January, calling the process “a farce that has been organized against the independence movement.”

For several years, Catalan nationalists have argued that Spanish democracy is skin-deep and that the legacy of the 1939-75 Francisco Franco dictatorship is alive and well in the country’s institutions.

Only a few years ago, such claims were rare: Spain’s economy thrived and its territorial structure—which gave 17 regions varying degrees of self-government—appeared to function effectively. But that started to change a decade ago, as the 2008-12 economic crisis eroded many of the country’s institutions, from its corruption-plagued political parties and royal family, to its mismanaged banks and under-resourced judiciary. Support for Catalan separatism, which until then had been relatively marginal, started to swell as the Spanish state’s weaknesses were exposed. The rigid response to this phenomenon by the then conservative government of Mariano Rajoy, which refused to negotiate Catalan nationalist demands, only fueled the discontent, culminating in 2017’s chaotic referendum. Spain catapulted to international headlines, shocking a world accustomed—understandably, although somewhat myopically, given twentieth-century history—to thinking of the country as stable.

Rajoy was ousted by a no-confidence vote last summer. But his decision to treat the Catalan crisis as a legal rather than political problem had far-reaching consequences. The onus has been on Spain’s courts ever since.

A particularly contentious aspect of the legal process has been the preventive custody of Cuixart, Sánchez, Junqueras, and six others, who have all waited in jail for a trial whose date was only announced days before it was due to begin. The Spanish authorities have argued that their incarceration was due to flight risk—seven Catalan leaders fled abroad after the referendum to Belgium, Scotland and Switzerland—and to prevent continued illegal activities. But the trial delays since then have made the measure look increasingly excessive.

Another controversial feature is the rebellion charge against nine defendants. Rebellion is legally defined as “rising up, violently and publicly” against the Spanish state— the last conviction followed an attempted coup d’état in 1981. The Catalan independence movement, despite its many faults, has been characterized by peaceful protest. There have been some violent incidents, such as police cars being vandalized or a well-known unionist journalist being punched while he was live on air, but these have been rare, and never linked to the movement’s leaders themselves.

Ironically, the most violent scenes of the independence push were caused by Spanish riot police on the day of the 2017 referendum. Targeting several of the improvised voting stations, they smashed windows and doors, dragging some voters away and beating others. The Spanish interior ministry has refused to probe the actions of its police officers on that day. Barcelona’s leftist city hall has brought a lawsuit against 33 of them.

The Spanish judiciary does have a history of overreaction. The Audiencia Nacional, a court dedicated to countering terrorism and organized crime, has in the last two years issued jail sentences against several hip-hop artists due to the content of their songs and social media accounts. Among them is Josep Miquel Arenas, a young rapper known as Valtònyc, who was given a three-and-a-half-year sentence for glorifying terrorism and insulting the monarchy in his angry, anti-establishment songs. Shortly before beginning his sentence last year Arenas fled to Belgium. The Spanish authorities are now trying to extradite him. Rapper Pablo Hasél was given a two-year jail sentence on similar charges last year, for the content of several tweets and the lyrics to one of his songs. The sentence was subsequently reduced to nine months on appeal.

Joaquim Bosch, a magistrate and outspoken critic of the Spanish justice system, has warned of “an obvious erosion of freedom of speech” in Spain. Jueces para la Democracia (Judges for Democracy), the progressive magistrates’ association he represents, argues that Spanish laws are too vague on issues of terrorism or hate speech, giving free rein to over-zealous investigators.

The recent spate of freedom of speech cases is grist to the mill of the Catalan independence movement, which runs a slick PR machine. Arenas, for example, has been photographed several times posing with former Catalan president Carles Puigdemont—who oversaw the 2017 independence referendum and fled to Belgium shortly afterward—since they both left Spain. In addition, there have been a handful of other cases which have cast in doubt the judiciary’s independence from political interference.

In November, the Supreme Court performed an unprecedented U-turn. Having recently ruled that banks, not customers, should pay a mortgage tax, the court changed its mind, drawing accusations that it had caved in to pressures from the country’s financial powers.

Weeks later, in a separate case, Supreme Court magistrate Manuel Marchena withdrew his candidacy to head up Spain’s judicial governing body. A leaked text message from a conservative senator had emerged, apparently gloating at the fact that Marchena’s appointment would allow the right-wing Popular Party to control the court “from behind the scenes.” Marchena will nonetheless preside the panel of judges handling the Catalan independence leaders’ trial.

As a result, it has been easy for secessionists to present their conflict with Spain as one upholding democracy against repression. Yet in pursuing their dream of an independent republic, Catalan nationalists have occasionally neglected their much-vaunted democratic values.

In 2015, the pro-independence Catalan government treated a regional election as a plebiscite on the secession issue. In it, pro-independence parties won a narrow majority of seats in the regional parliament but fell short of a majority of the popular vote. Nonetheless, secessionists pushed ahead with their divisive roadmap as if they had secured an overwhelming mandate. Then, in September 2017, the pro-independence majority rode roughshod over parliamentary protocol to ram through laws laying the groundwork for the October referendum.

For Joan Coscubiela, a member of the Catalan parliament for the leftist Catalunya Sí que es Pot (Catalonia Yes We Can) coalition at the time, those parliamentary sessions “ended up installing in people’s minds the idea that democracy means the majority can do whatever they like, even if it means breaking the rules [and] trampling over the rights of the minority.”

Many Catalans have been dismayed at how the issue of separation from Spain has dominated their region’s political debate, distracting attention from more urgent matters, such as public healthcare and education.

The upcoming trial could see the figureheads of Catalonia’s failed independence bid pay a high price for such single-mindedness. But Spain’s judiciary will be up for evaluation as well. Spanish authorities have rejected calls for international observers, insisting that the justice system offers the guarantees and transparency necessary for such a high-pressure legal process. This trial’s ability to deliver on that promise could tell us a good deal about the health of Spanish democracy—and whether or not worries about it are justified.

Pork rinds in Tabasco sauce. Cheeseburger pizza. Well-done steak with ketchup.

Cory Booker can’t eat any of these presidential favorites. The U.S. senator from New Jersey, who announced his candidacy for president earlier this month, is a vegan, meaning he doesn’t eat food that’s made of, or from, animals. Meat is off the table, as is anything with milk, cheese, or eggs. So Booker can’t indulge in smoked salt caramels, as Obama did, because they contain milk chocolate. He can’t even eat the jelly beans that Ronald Reagan loved because they’re made with gelatin, which includes animal collagen.

Booker is looking to make history with his 2020 bid. America has never elected a vegetarian president before, much less a vegan. Before Booker, a vegetarian had never even been elected to the Senate before. (He says he switched fully to veganism on Election Day 2014.) There are no self-identified vegans currently in the House of Representatives, and only a handful of vegetarians.

Some might argue that there’s a dearth of plant-eaters in public office because there aren’t that many in the U.S. overall. Around 8 percent of Americans identify as strict vegan or strict vegetarian, a figure that has remained steady for the last two decades. But that’s still about 26 million people who have barely had any representation in Washington. Their numbers are similar to other chronically underrepresented identity groups. LGBTQ Americans make up only 4.5 percent of the population. Black and Hispanic Americans make up about 13 and 18 percent, respectively.

The political and cultural forces that privilege white, straight, Christian men in the halls of power are well known. But why do voters consistently put meat-eaters in the White House? How hard would the meat industry—and meat-lovers—fight to keep that in place? Booker’s candidacy provides a unique opportunity to find out.

The power that meat plays in American politics has never been truly tested before. Ben Carson is a vegetarian, but he never really talked about when he ran for president in 2016. It didn’t shape his political identity.

Booker talks about his diet all the time. When he campaigned for Hillary Clinton in 2016, he joked that he was campaigning as her VP—or “vegan pal.” He posts pictures of vegan food to his Twitter and Instagram feeds. He serves vegan dishes to members of Congress. He talks about the benefits a vegan diet could have for African Americans, who suffer disproportionately from heart disease and high cholesterol. If he won the Democratic nomination, Booker would become the most high-profile plant eater in the country—after Beyoncé, anyway.

The 49-year-old senator makes a moral argument for his veganism. “I began saying I was a vegetarian because, for me, it was the best way to live in accordance to the ideals and values that I have,” Booker, who did not respond to my requests for an interview, told VegNews recently. “You see the planet earth moving towards what is the Standard American Diet. We’ve seen this massive increase in consumption of meat produced by the industrial animal agriculture industry. The tragic reality is this planet simply can’t sustain billions of people consuming industrially produced animal agriculture because of environmental impact.”

Still, Booker has said he doesn’t believe his diet will be a factor in the minds of 2020 voters. “I think people are concerned about what kind of leader I’ll be,” he told The Atlantic’s Julia Ioffe last year. “When I go around New Jersey, nobody’s asking me about my personal life.”

Lawrence Rosenthal, who heads up the Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies, disagrees. “The likelihood is good the [Republicans] will go after Booker for this,” he said in an email. There is “considerable precedent,” he argued, for Republicans using personal behavior such as diet to portray Democrats as elitist and out of touch. A 2004 attack ad against Howard Dean, for example, portrayed him as “latte-drinking” and “sushi-eating.” The idea, Rosenthal said, was to “play into the ‘us versus them’ sentiment (largely resentment) that is the prime motivator of populist politics—the ‘real Americans’ versus the (in this case cultural) ‘elites.’”

Obama experienced something similar during his first presidential run, in a pseudo-scandal known as “Arugula-gate.” At an Iowa farm in 2007, Obama railed against the high price of produce in America. “Anybody gone into Whole Foods lately and see what they charge for arugula?” he said. “I mean, they’re charging a lot of money for this stuff.” This was used by the right as evidence that Obama had “simply worn silk stockings and rode in limos far too long.”

Presidential candidates from both parties often use food as a way to relate to voters on the campaign trail. But what constitutes relatable food is almost always unhealthy and animal-based. At the Iowa State Fair, presidential candidates seek photo ops with a 600-pound cow carved out of butter, fried candy bars on sticks, and hot beef sundaes. By campaigning as a vegan, Booker “risks coming across as removed from the hoi polloi,” Michael Dorf, an animal rights law professor at Cornell, wrote last year. “He cannot show his love for all things Americana by eating a stick of deep fried butter at the Iowa State Fair.”

It’s also possible that, in an era where “Soy Boy” has become a popular alt-right insult, Booker’s conservative opponents will use his veganism to belittle him. “The idea that soy is a phytoestrogen, and thus men who consume it are less masculine than meat-eaters, is often expressed by people on the far right,” said George Hawley, an assistant political science professor at the University of Alabama. Hawley doesn’t believe the far-right will be as active in the 2020 election cycle, but mainstream Republicans still use food to attack liberals. Ahead of last year’s midterm elections, Senator Ted Cruz attacked his opponent, Beto O’Rourke, by claiming he “wants Texas to become like California, right down to the tofu.”

But one should not expect to find disdain for Booker’s veganism exclusively on the right. Americans from all political leanings tend to find vegans, well, annoying. Meat-eaters often feel that vegans are morally judging them, or even trying to impose their diets on everyone else. Booker’s opponents, especially those who disagree with his environmental positions, may appeal to those sentiments for campaign ads.

Pundits have already shown it’s done. In a 2015 op-ed in The New York Post, Eliyahu Federman accused Booker of “animal-rights extremism” for co-sponsoring a bill limiting antibiotics in livestock, supporting New Jersey legislation to ban gestation crates for pigs, and pushing for a no-kill animal shelter in Newark. In a then-recent interview, he wrote, “Booker talked as if it’s all personal, explaining how ‘being vegan for me is a cleaner way of not participating in practices that don’t align with my values.’ Problem is, he plainly wants to impose those values on the rest of us.”

Such attacks seem all but inevitable as the presidential campaign season accelerates. But that doesn’t mean they’ll work. Strict vegetarians and vegans may not be growing as an interest group, but Americans are warming to the idea that they should be eating more plants—not just for the environment, but their own health. People who identify as “flexitarians”—eating mostly plant-based, but cheating a little—now make up about a third of the population, and 52 percent of people report trying to incorporate more plant-based meals in their diet.

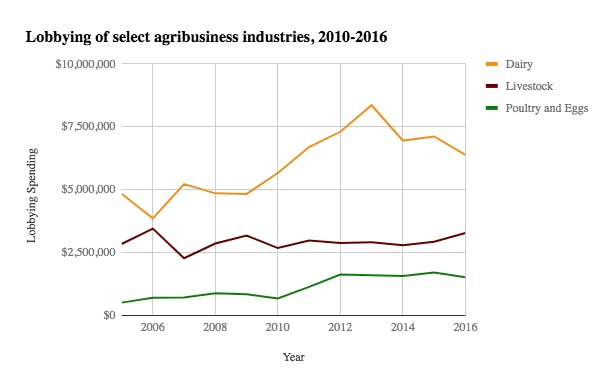

opensecrets.org

opensecrets.orgThe meat and dairy industries haven’t taken this cultural shift lightly. As the popularity of plant-based products grows, the dairy industry is lobbying Congress and the FDA to demand that soy and almond milk producers stop using the word “milk” on their labels, and the beef industry wants to make sure plant-based burgers can’t use the word “meat.” The beef industry also spent millions making sure the Department of Agriculture didn’t listen to scientists, health and climate advocates who said nutritional guidelines should be changed to recommend Americans eat less meat.

The meat industry has considerable political muscle to flex. It contributes about $894 billion in total to the U.S. economy, according to the North American Meat Institute. “That size translates into political influence,” The Atlantic reported in 2015. “In 2014, the industry spent approximately $10.8 million in contributions to political campaigns, and an estimated $6.9 million directly on lobbying the federal government.” An OpenSecrets analysis of agribusiness lobbying shows that the meat and dairy industries’ political spending spikes as demand for those products fall. How will they respond when a vegan starts making waves on the campaign trail?

Even the Iowa State Fair now has vegan options. “Cory Booker can come to my stand,” said Connie Boesen, a Des Moines City Council member who’s been running her Applishus stand for 34 years. She sells multiple things on a stick: peanut butter and jelly, fruit, and even salad (essentially a skewer of cubed peppers, mushroom, carrots, cucumbers and lettuce). If Booker doesn’t want to partake in the usual candidate photo-op of flipping a pork chop, Boesen said, “I’ll invite him to come slice an apple.”

On a steamy Sunday last July, at about half-past noon, a caravan of unmarked SUVs exited the FBI’s Washington, D.C., field office, an eight-story concrete building that exudes all the charm of a supermax prison. The cars moved swiftly across the city; speed was critical. There were indications that the target, who had canceled the lease on her apartment and packed her belongings, was about to take flight.

Just before one o’clock, the SUVs turned off Wisconsin Avenue and into a parking lot at 3617 38th Street NW, a low, red-brick apartment building near American University. Armed agents in bulletproof vests filled a narrow corridor outside apartment 208. Inside, Maria Butina was watching the Wimbledon men’s final on TV and preparing for a long drive in a U-Haul truck to South Dakota. Having just graduated from American University with a master’s degree in international affairs, she was about to start working as a consultant in the cryptocurrency industry. Her boyfriend of five years, a 57-year-old Republican activist named Paul Erickson, would be traveling with her to his home in Sioux Falls.

“Everything was boxed up,” Erickson told me. “The last thing to do was to pack the electronics, to unplug the TV and the internet. And then pound! Pound! Pound! I answered the door, and there was a team of six agents in the hallway.” Three of the agents surrounded Erickson while the other three went after Butina. “The team went in, dragged her out, spun her around, cuffed her in the hallway, and announced her arrest,” Erickson said.

According to federal prosecutors, Butina’s graduate studies, and her relationship with Erickson, were just a cover; in reality she was a clandestine Russian agent sent to the United States to use sex and seduction to infiltrate conservative political circles and influence the White House’s policies toward Russia. Denied bail out of fear she might run to the Russian Embassy, or jump into an embassy car, she was charged with violating Section 951 of the U.S. Code: acting as an unregistered agent of a foreign power, as well as with a conspiracy charge associated with it. She is the only Russian arrested to date in the government’s ongoing investigation into the Kremlin’s efforts to interfere with the 2016 presidential election.

Slim and stylish, with long red hair flowing halfway down her back, Butina seemed to fit the stereotype of a Russian spy popularized by figures like Anna Chapman, the Russian sleeper agent arrested in New York in 2010, as well as the fictional spy-seductress played by Jennifer Lawrence in the movie Red Sparrow and the Soviet operative played by Keri Russell in the TV series The Americans. “Real-life ‘Red Sparrow’? Court Filings Allege Russian Agent Offered Sex for Access,” blared an ABC News headline. “Maria Butina, Suspected Secret Agent, Used Sex in Covert Plan, Prosecutors Say,” declared The New York Times.

Since August 17, Butina has been housed at the Alexandria Detention Center, the same fortresslike building that holds Donald Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort. On November 10, she spent her 30th birthday in solitary confinement, in cell 2F02, a seven-by-ten-foot room with a steel door, cement bed, and two narrow windows, each three inches wide. She has been allowed outside for a total of 45 minutes. On December 13, Butina pleaded guilty to conspiracy to act as an unregistered agent of the Russian Federation. She faces a possible five-year sentence in federal prison.

With anti-Russia fervor in the United States approaching levels directed at Muslims following the attacks of September 11, 2001, it was easy for prosecutors to sell the story of Butina as a spy to the public and the press. But is she really? Last February, Robert Mueller, the special counsel leading the Russia probe, indicted 13 Russian spies for interfering with the 2016 election. And in July, two days before Butina was arrested, Mueller charged twelve more Russians with hacking into email accounts and computer networks belonging to the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. It is not inconceivable that Butina is among their ranks.

Yet a close examination of Butina’s case suggests that it is not so. Butina is simply an idealistic young Russian, born in the last days of the Soviet Union, raised in the new world of capitalism, and hoping to contribute to a better understanding between two countries while pursuing a career in international relations. Fluent in English and interested in expanding gun rights in Russia, she met with Americans in Moscow and on frequent trips to the United States, forging ties with members of the National Rifle Association, important figures within the conservative movement, and aspiring politicians. “I thought it would be a good opportunity to do what I could, as an unpaid private citizen, not a government employee, to help bring our two countries together,” she told me.

The government’s case against Butina is extremely flimsy and appears to have been driven largely by a desire for publicity. In fact, federal prosecutors were forced to retract the most attention-grabbing allegation in the case—that Butina used sex to gain access and influence. That Butina’s prosecution was launched by the National Security Section of the District of Columbia federal prosecutor’s office, led by Gregg Maisel, is telling in itself: According to a source close to the Mueller investigation, the special counsel’s office had declined to pursue the case, even though it would have clearly fit under its mandate.

Despite the lack of evidence against Butina, however, prosecutors—abetted by an uncritical media willing to buy into the idea of a Russian agent infiltrating conservative political circles—were intent on getting a win. In the context of the Mueller investigation, and in the environment that arose after Trump’s election, an idealistic young Russian meeting with influential American political figures sounded enough like a spy to move forward.

Butina told me her story over a number of long lunches starting last March at a private club in downtown Washington, D.C. She was always early, except on April 25, when she didn’t show up.

She later apologized; a dozen FBI agents had raided her apartment. “They knocked on the door, and that knock I will never forget,” she told me. “They pushed me inside, told me to sit down. I was completely in shock, but what could I do?” The agents searched her apartment for approximately seven hours, apparently looking for hidden transmitters or other evidence of spy-craft. “It was a horrible day in my life,” Butina said. The FBI found nothing, however. There was no mention of spy gear in her indictment, and there were no charges of espionage.

This was the second time the U.S. government had sifted through Butina’s personal life. Nine days earlier, in response to a request from the Senate Intelligence Committee, she voluntarily turned over more than 8,000 documents and electronic messages and testified in a closed hearing for eight hours. But they also uncovered nothing incriminating.

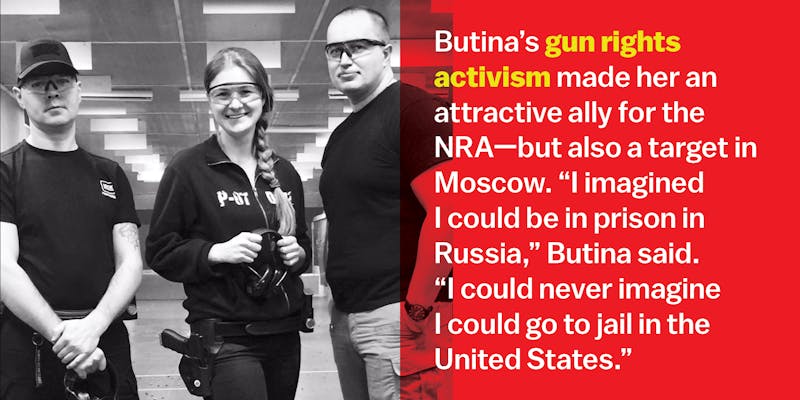

“Look, I imagined I could be in prison in Russia. I could never imagine I could go to jail in the United States. Because of politics?” Butina told me over the phone a few weeks after she was taken into federal custody. It was one of a series of exclusive interviews I conducted with Butina, Erickson, and other prominent figures involved in the case, none of whom have spoken previously to the media. “I didn’t know it became a crime to have good relations with Russia—now it’s a crime,” she told me earlier. “They hate me in Russia, because they think I’m an American spy. And here they think I’m a Russian spy.”

“If I’m a spy,” she added, “I’m the worst spy you could imagine.”

Butina was born on November 10, 1988, in the remote Siberian city of Barnaul. Part of the first post-Communism generation, she developed a passion for politics and international relations. In 2010, she graduated from Altai State University in Barnaul with master’s degrees in political science and education. After running unsuccessfully for a position in the local government, she opened a small chain of furniture stores. Hoping to expand her business, she moved to Moscow in August 2011, at the age of 22, but quickly realized that the commercial competition in the capital was too great for her to succeed. Instead, she turned back to political activism and the issue of gun rights.

Photo courtesy of Maria Butina

Photo courtesy of Maria Butina Gun ownership in Russia is highly restricted. With few exceptions, handguns are illegal, and guns for hunting and sport are difficult to obtain. “The checks were incredibly hard just for a shotgun,” Butina told me. “For a rifle, you have to have been an owner of a shotgun with no problems with the law.” But, as in the United States, support for gun ownership in Russia has been growing in rural areas. “The strongest support is outside Moscow,” she said, particularly among conservative, middle-aged Russian men who view guns as a way to protect their families. “Self defense—that was the issue that they were fighting for,” Butina said.

At the time, the NRA was also looking to expand internationally, and Butina was surprised at how similar their outlooks were. “They were talking about guns in exactly the same way we do,” she said. “That formed my idea that if we ever want to build a truthful friendship between the U.S. and Russia … it should be people based, not leaders based.”

The idea that citizens should be allowed to carry firearms had been one of the most popular issues in Butina’s campaign for political office, and she had started a small gun rights group in Barnaul. Soon after arriving in Moscow, she placed a notice on the internet asking anyone in the city interested in supporting the legalization of weapons to meet at a local restaurant. “A lot of people showed up,” she said. “This is how the whole movement started.” As the organization grew, they chose a name, the Right to Bear Arms, and began to hold regular meetings. By 2014, they had collected 100,000 signatures in support of legislation that would grant citizens the right to defend themselves and their property using deadly force.

The group itself was consciously modeled after the NRA. “It was created as the Russian version of the NRA, and we wanted to have as much NRA involvement as possible,” said a former member, who asked that his name not be used because of fear of retaliation in Russia. But unlike the NRA, which has become closely aligned with the conservative movement in the United States, Butina’s group sought support from across the political spectrum. “I’m an advocate for gun rights,” Butina said. “For me it didn’t matter, I talk to left or right, in government or oppositional. I had a slogan written on the door of my office that anyone who supports gun rights may come in, but you leave your flag behind.”

Butina became well-known for her public support of gun rights in Russia, appearing frequently on television, in newspapers and magazines, and at rallies and protests. The work was, at times, dangerous; Russian President Vladimir Putin instinctively distrusts activist organizations, and surveillance was pervasive. “She was under constant FSB surveillance in Russia,” said Erickson, speaking of the Russian intelligence agency. “They would go to all the public meetings of her group, and they would go to all the rallies. Sometimes just show up in her offices once a week.” Putin also has a long history of opposing gun rights. Last October, he ordered the Rosgvardia, the national guard, to get tougher when it comes to guns.

“We were watched,” Butina told me, “but unless you crossed the line, no one’s going to go to prison. The question becomes: Do you cross this line? Do you become dangerous to the regime at a certain point? I had a bag packed in my hallway at home in case I’m imprisoned, somebody can bring it to me. That’s my reality.”

On October 30, 2013, Butina drove to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport to meet two Americans who she hoped would lend support to her fledgling organization: David Keene, a former president of the NRA, whom Butina had invited to speak at the second annual meeting of the Right to Bear Arms; and Paul Erickson, who had come along as Keene’s “body man.” The two men had deep ties to America’s conservative power centers. In addition to serving as the NRA’s president, Keene, now 73, was the former chairman of the American Conservative Union. If Keene had been a general in the conservative movement, Erickson was a seasoned guerrilla fighter. Between campaign stints for Ronald Reagan, Pat Buchanan, Richard Viguerie, and Mitt Romney were far-flung missions in support of anti-Soviet rebel forces in places like Angola, Nicaragua, and Afghanistan. (On February 6, a federal grand jury indicted Erickson on 11 counts of wire fraud and money laundering in a case unrelated to Maria Butina.)

Butina and Keene had become acquainted through a mutual friend: Alexander Porfiryevich Torshin. A passionate pro-gun enthusiast, Torshin, 65, was a senator in the Duma and the first deputy chairman of the Federation Council, the upper chamber of Russia’s Parliament. Torshin was an early supporter of Butina and the Right to Bear Arms. “We will start organizing our own Russian NRA,” he tweeted in 2012, shortly after meeting Butina. A month later, he invited her and other gun rights supporters to the Duma for the first of a number of meetings to discuss possible legislative action to loosen gun regulations.

Torshin traveled frequently to the United States. “His obsessions were coming to the United States twice a year for the NRA and the National Prayer Breakfast,” said Erickson. Keene, who described Torshin as “sort of the rabbi of gun rights in Russia,” had met him years earlier on one of these trips, and the two had developed a friendship.

“Keene is a very astute judge of character,” said Erickson. “He spoke to Torshin, got to know him a little bit, and came to decide that Torshin was an honest man, which is rare in Russian politics.” At one point, Keene had invited Torshin to talk to the NRA’s legislative affairs committee in Washington. That, in turn, led to the invitation from Butina that brought Keene and Erickson to Moscow.

Photo via Instagram

Photo via InstagramKeene and Erickson were convinced that the Right to Bear Arms was a genuine organization, and that Butina was a forceful leader. “We watched over the course of nine hours that day her run this thing like the Trans-Siberian Railroad, boom, boom, boom,” Erickson said. “What Maria had built, over that year and the next—she eventually peaked at almost 10,000 members nationwide—it was real. It was not a false front.” For Keene, it was an opportunity to renew his friendship with Torshin, and also to assess Butina, a relative newcomer in the global gun rights movement. As Erickson recalled, Keene told him, “We think that this group is probably real, but we don’t know. It’s worth a trip to meet this woman.” Erickson and Keene were initially skeptical of Butina’s ability to lead a national group. “These were rural farmers and urban industrial workers; big men, hard men, and very dedicated,” Erickson said. Would they really follow Butina? Their opinion changed when they saw her address the several hundred attendees at a conference center near the banks of the Moscow River. “She strides to the podium, steps up on the stage, slams a gavel, calls the thing to order, and in machine-gun Russian, staccato Russian, starts this thing off,” Erickson said. “And all the guys in the rear stepped back.”

Five months later, Butina made her first visit to the United States. Keene had invited her to attend the NRA’s 2014 convention in Indianapolis and tour the group’s headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia. On her public blog, Butina posted a photo of herself and Keene outside the building. “An experience at the Washington office of the NRA,” she wrote. Butina updated her blog frequently with details about the places she visited, events she attended, and people she met, including politicians.

Back home in Moscow, the Russian government was making note of her new friendships. The previous month, the United States and Russia had clashed over the invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea, and the United States had levied sanctions against Russia. Keene adopted the prevailing attitude of the government, and wrote an editorial in The Washington Times denouncing “Russia’s aggression.”

Shortly after Butina posted the photo of her and Keene at NRA headquarters, Marika Korotaeva, a Kremlin official and the former head of the Department for Internal Policy at Putin’s presidential office, got in touch with her boss, Timur Prokopenko. “Hey. Help please,” she wrote. “Butina ... is now posting pictures with the president of the National Rifle Association at the main office in Virginia. Against the backdrop of statements about the supply of arms to Ukraine, I ask your help.... We have to shut her down completely.” (The text was part of a large batch of messages made public by a group of Russian hackers who had targeted Prokopenko.)

Russian authorities continued to monitor Butina and, according to Erickson, attempted to recruit her as an informant. As U.S. prosecutors later noted, during a search of Erickson’s apartment in South Dakota, FBI agents discovered a handwritten note: “How to respond to FSB offer of employment?” To U.S. authorities, this was evidence that Butina had ties to the Russian intelligence service. According to Erickson, however, the opposite was true. Butina had no interest in working for the FSB, he told me, adding that he was the one who had written the note before one of Butina’s trips to Moscow. He was simply helping her prepare for the inevitable questioning she would face back home. “A question they always asked is, ‘Perhaps you’d like to make a more formal relationship,’” Erickson said. “How do you answer that to say ‘no’ in such a way that it doesn’t get you in trouble?”

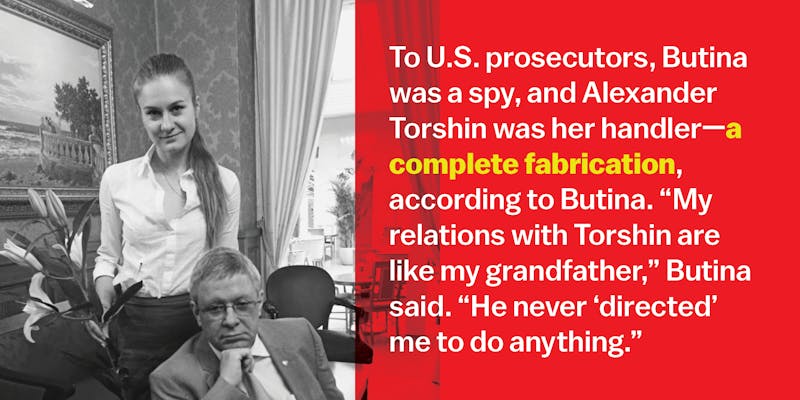

In January 2015, Torshin was appointed deputy governor of the Central Bank of Russia, the equivalent of the U.S. Federal Reserve. Over the next few years, he and Butina traveled together to the annual NRA conventions and hosted senior NRA members in Moscow. Butina translated for Torshin, who spoke no English. At one point, after a host in the United States asked if they would like one hotel room or two, Torshin made business cards that listed her as his “special assistant.” Prosecutors would later use this made-up title as evidence that she was an employee of the Russian government, although Butina said the cards were meant to keep anyone from mistaking her relationship with Torshin for a romantic one. “My relations with Torshin are like my grandfather,” she told me. “He never ‘directed’ me to do anything, since I didn’t work for him or the government.”

In April 2015, Torshin and Butina joined more than 78,000 people in Nashville at the NRA’s convention—“nine acres of guns,” according to one of the event’s ads. With the presidential election a little more than 18 months away, a dozen Republican hopefuls also crowded in for short speeches. Butina circulated among the candidates and had her picture taken with Scott Walker, the Wisconsin governor and presidential candidate, to whom she was introduced by David Keene. She was surprised that Walker was able to speak a few words in Russian. “We talked about Russia,” she wrote on her blog. “I did not hear any aggression towards our country, the president or my compatriots. How to know, maybe such meetings are the beginning of a new dialogue between Russia and the US and back from the Cold War to the peaceful existence of the two great powers?!”

The government later characterized this encounter as evidence of Butina’s tradecraft as a spy, part of Russia’s larger “influence operation.” According to the FBI’s affidavit against her, Butina was a “covert Russian agent” working “at the direction” of Torshin on behalf of the Russian government to“develop relationships with American politicians in order to establish ... ‘back channel’ lines of communication.” All of Butina’s travels and meetings within the United States, in this light, were evidence of a plot “to penetrate the U.S. national decision-making apparatus to advance the agenda of the Russian Federation.”

Photo via Facebook

Photo via Facebook Keene scoffed at the idea. “She was a typical mid-twenties young woman interested in politics, and she wanted to have her picture taken,” Keene told me. “She was no different from 200 similar women you’d meet here or anywhere else. If this is their idea of a spy, they’re really hurting.”

In February 2016, Butina traveled again to the United States to give a talk at the Conference on World Affairs in St. Petersburg, Florida. Before that, however, she traveled to the Safari Club International Convention in Las Vegas with Joe Gregory, a wealthy member of the NRA whom she had met in Moscow. An annual jamboree for camo-loving trophy hunters, held at the Mandalay Bay hotel, the Safari Club convention featured “pay to slay” auctions—where attendees bid to join big-game safaris to kill animals like lions and leopards—and live music from Merle Haggard and Blood, Sweat & Tears. Torshin was there, and Butina called Erickson to see if he wanted to join them. “He says, ‘Well, I actually have a friend who is a big hunter and who likes Russia and believes in peace with U.S.-Russia friendship,” said Butina. “And if you would like to meet him, he’s there.”

The friend was George D. O’Neill Jr., 68, great-grandson of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and an heir to the Rockefeller fortune. He and Erickson had known each other since the early 1990s, when Erickson was running Pat Buchanan’s presidential campaign. In 2010, O’Neill and his father sponsored a joint U.S.-Russia conference in Moscow. “I met Torshin long before I met Maria,” O’Neill told me. “He was a Gorbi guy—a Gorbachev person—and that’s where this impulse to work with America came from. That’s what he told me.”

In Las Vegas, Butina and O’Neill discussed ways to bridge the differences between their two countries. A short while later, she received an invitation from him saying he would like to host dinners for “intellectuals who believe in U.S.-Russia friendship.” The purpose of the dinners was “to promote a Realistic and Restrained Foreign Policy and work to substantially improve the relations between Russia and The United States. I have no other agenda.”

As Butina was looking into master’s degree programs in the United States, O’Neill offered to assist with her finances. The help was critical, since her parents in Siberia could not afford the expense. Torshin, her supposed handler, never offered to help pay her two-year tuition. Instead, it was O’Neill, and her boyfriend Erickson, who gave her the money to enroll at American University’s Graduate School of International Service. Unlike Scott Walker, whom Butina met in passing, and whom she would later be accused of attempting to influence, her real ties were to men like Erickson and O’Neill, who had a few connections in Washington but in reality had little to no power. Still, Butina was eager to play a role in O’Neill’s quiet campaign to open an informal U.S.-Russia communications channel on the eve of the election, and O’Neill saw in Butina someone who could help with that project.

Torshin did want to help Butina and O’Neill, however. He was a “Gorbi guy” after all, and had taken part in O’Neill’s earlier U.S.-Russia friendship conference in Moscow. He had also been a regular visitor to the United States for a decade or more, and he regarded Butina as a friend and protégé. Butina told Torshin that O’Neill “enjoys proximity to the formation of the future White House administration (regardless of which side wins),” and that the gatherings “should help the White House experts form the correct outlook towards Russia.” Torshin conveyed his strong approval. Torshin was “very much impressed by you and expresses his great appreciation for what you are doing to restore relations between the two countries,” Butina wrote to O’Neill, according to the FBI’s affidavit. “He also wants you to know that Russians will support the efforts from our side.” It was one more piece of evidence the government used against Butina.

In April 2016, as the political season was heating up in the United States, Butina and Torshin also discussed the possibility of Torshin attending the NRA convention the following month, according to private Twitter messages the FBI recovered from Butina’s computer. Torshin wasn’t sure he could go, because the timing of the conference conflicted with his duties at the Central Bank of Russia. “I hope your female boss will understand,” Butina wrote to Torshin on April 28. “This is an important moment for the future of our country.”

These were the naïve hopes of a grad student, not the plotting of a Kremlin operative, as the U.S. government alleged. Had Butina been a spy and Torshin her handler, she surely would have been ordered to begin cultivating a real person of influence—there were hundreds out there—and not an idealistic outsider like O’Neill. Yet U.S. authorities cited all these messages as evidence that she was working on behalf of the Russian government. (When I contacted Torshin for an interview, he replied, “I consider it advisable to do this after the publication of the results of all the investigations in the United States.”)

The May dinner was held in the Washington Room at the Army Navy Club, not far from the White House. A dozen people were seated beneath a copy of George Washington’s yellowed parchment commission naming him commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Made up of a cross-section of Washington literati, the group included the publisher of a conservative magazine, the head of a Libertarian think tank, a Hollywood producer, the liberal leader of a foreign policy discussion forum, and the head of a Eurasian policy group. “Maria shows up with Paul Erickson,” said a lawyer who attended but asked that his name not be used, “and George introduced both of them to us.” He added that Butina told everyone that she was a close friend and associate of Torshin, and that they had known each other for years. “If this woman’s a spy, then getting up and disclosing this information is not the way you would do it,” he said.

O’Neill preferred to conduct his friendship dinners in private, but in the summer of 2016, with the news filled with allegations of Russian interference in the election, maintaining a low profile was difficult. This was especially troubling for Butina. “Right now I’m sitting here very quietly after the scandal about our FSB hacking into the [Democratic Party’s] emails,” she wrote to Torshin in July 2016, referring to the messages released by WikiLeaks on July 22 by suspected Russian hackers. “My all too blunt attempts to befriend politicians right now will probably be misinterpreted, as you yourself can understand.” Torshin was sympathetic but unable to help. He simply told her that she was “doing the right thing.”

As she began classes at American University, Butina continued to help O’Neill organize his dinners. Among the people she invited, at the urging of Erickson, was J.D. Gordon, a former Navy commander and Pentagon spokesman whom she had met at a social function on September 28, 2016. He had spent the previous six months as director of national security on the Trump campaign and was anticipating a position of continued influence if Trump was elected. The next day, according to documents I was able to obtain, Butina sent Gordon an email.

“These dinners were started by George O’Neill, a conservative American businessman who’s also a public policy genius,” she wrote. “The dinners are private, off-the-record, and NO ONE is ever there in their ‘official’ capacity. It’s just a chance to talk about what smart future diplomacy might look like.”

A few hours later, Gordon emailed back saying he couldn’t make the dinner. But he did include a link to a Politico article that listed him as a member of Trump’s “New Brain Trust,” and that referred to him as the “Trump national security adviser,” who “is shifting to the transition to focus on veterans and national security.” A couple of weeks later, Gordon invited Butina to attend a Styx concert. She accepted, and later went to Gordon’s birthday party, along with half a dozen other people. That was the extent of their relationship. Gordon sent Butina a few more emails asking to get together again. In one, he boasted about a recent trip to Europe where he “met with a couple of Foreign Ministers, a Deputy Prime Minister and dozens of other government officials,” and added, “one of my co-hosts, a former Hungarian Ambassador to the EU, said I rcvd more press in Budapest … than Vladimir Putin.” But Butina never replied.

The nature of this relationship is important to consider in the context of what came later. To a Kremlin-directed agent of influence, as Butina supposedly is, Gordon would seem to have been the perfect catch: a senior military officer with high-level Pentagon connections, a widely quoted Washington insider, and, most important, a key national security link to Trump on the eve of the election. Yet instead of recruiting him, Butina dismissed him, because her interest was helping O’Neill with his dinners, not Moscow with its spying. Equally strange for a supposed secret agent, she never bothered to tell Torshin about Gordon, something that would normally get both the secret agent and the handler a nice Kremlin promotion.

Following Trump’s election, and the barrage of allegations about Russian interference, the political climate grew even more toxic. But when Torshin announced that he was planning to bring a group of prominent Russians with him to the National Prayer Breakfast in February, just after the inauguration, O’Neill agreed to host another of his dinners. Butina again helped with the guest list. Since first arriving in the United States, she had spent much of her time networking with conservatives and members of the Republican Party. Now she was actually going to bring them together with fellow Russians and hopefully establish an informal back channel of communication between the two countries. “People in the list are handpicked by [Torshin] and me and are VERY influential in Russia,” Butina wrote to Erickson on November 30, 2016.

Months earlier, Butina and Torshin had even flirted with the idea of getting Putin himself to lead the Russian delegation to the prayer breakfast. Ukraine’s former prime minister had attended the 2016 gathering, where President Barack Obama had given an address. Butina and Torshin believed that Putin’s attendance, so soon after the presidential election, would be a large step toward improved U.S.-Russia relations. “Torshin says, ‘Let me talk to somebody in the Kremlin and maybe the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,’” Butina told me. But the idea went nowhere. And while Torshin was able to obtain approval to attend the 2017 prayer breakfast, the Russian government declined to send official representatives. “There will be no state leaders and delegations,” Torshin told Butina in an email obtained by the FBI. Still, to U.S. authorities, the fact that Butina and Torshin were even talking to the Russian government—and inviting “influential” Russians to attend O’Neill’s dinner and the prayer breakfast—was proof that they were working for the Kremlin.

The FBI has never revealed why it began investigating Butina, but it was probably as part of an inquiry into Torshin’s possible ties to the Russian mafia, which the FBI was alerted about in 2012. The special agent eventually assigned to Torshin’s case was named Kevin Helson. Helson worked for the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation’s forensics lab in Knoxville, analyzing blood smears and latent fingerprints, before joining the FBI. He was an odd choice to lead a complex, politically charged counterintelligence investigation of the deputy chief of the Central Bank of Russia. Helson’s partner was Michelle Ball, who had previously worked as a local news reporter and part-time anchor for a Biloxi, Mississippi, television station. She appears to have had no experience in anything related to the law, Russia, or counterintelligence.

By the summer of 2017, about two years after the investigation began, the U.S. government had yet to find anything with which to charge Butina. Gregg Maisel and his team of prosecutors didn’t give up, however. One idea was to show that Butina was the conduit for illegal cash going from Putin to the Trump campaign, via Torshin and Butina’s ties to the NRA. The NRA had reported spending $30 million to support Trump, almost triple what it donated to Republican candidate Mitt Romney in 2012.

The investigation was dutifully leaked to the press. “FBI Investigating Whether Russian Money Went to NRA to Help Trump,” read a McClatchy headline last January, with Butina mentioned as possibly involved. But the investigation produced no evidence of illicit cash transfers.

The inquiry by the Senate Intelligence Committee and the FBI’s surprise raid on Butina’s apartment also failed to turn up anything incriminating. Years of physical surveillance, which, according to a knowledgeable source, included secretly following her to interviews with me, at a cost of perhaps $1 million or more, also came up empty.

Lacking evidence of espionage, money laundering, passing cash to the Trump campaign, violating Russian sanctions, or any other crime, prosecutors finally turned to Section 951, acting as an unregistered agent of a foreign power. Based on the Espionage Act of 1917, the law was enacted in 1948 during the “Red Scare,” a time when Senator Joseph McCarthy exploited the exaggerated fears of Communist infiltration of government, the film industry, and other parts of society.

The few cases that have been brought under the statute involved targeting “sleepers” and other deep-cover spies sent to the United States without diplomatic immunity, and therefore subject to arrest. But while rarely used, it is also very broad. “We used to joke,” said a former FBI counterintelligence supervisor, “that’s what you use if you didn’t really have any evidence, because it would have been such an easy thing to find evidence whether it was there or not.”

It was a weak case. According to the FBI’s affidavit, Butina’s low-level networking with conservative activists and politicians, her efforts to help O’Neill with his dinners, and even her idealistic thoughts about bringing the two countries closer—the affidavit cites a statement Butina made to Torshin that, by inviting NRA officials to Moscow, “maybe … you have prevented a conflict between two great nations”—were part of a sinister, anti-American plot. This sort of insinuation and assumption is, essentially, the beginning and the end of the case against Maria Butina.

Among the FBI’s key pieces of evidence is a four-year-old email exchange with Erickson in which Butina fantasizes about a possible “diplomacy” project aimed at building constructive relations between Russia and the United States and suggests that such a project would require a budget of $125,000, for her to attend conferences and the Republican National Convention. What Helson didn’t mention in the affidavit, however, is that because there was never any funding from Torshin, the Russian government, or anyone else, there was no influence operation. It was talk, nothing more.

Helson also described a search of Butina’s computer, during which he discovered another four-year-old conversation, this time with Torshin, in which they discussed an article Butina had published in The National Interest calling for improved U.S.-Russia relations. “BUTINA asked the RUSSIAN OFFICIAL to look at the article,” the affidavit states, “and the RUSSIAN OFFICIAL said it was very good.” She sent him an article to read. Torshin read it and liked it. Therefore, Butina is a spy. This is the quality of the FBI’s case. When Scott Walker announced his presidential candidacy, Torshin asked Butina to “write [him] something brief,” which she did. This, too, became another piece of evidence for Helson, further proof that Butina was a covert Kremlin operative. Such mundane revelations go on for a dozen pages.

Yet there was no evidence that Butina was under the orders, direction, or control of either the Russian government or Torshin. Torshin exhibited no power or authority over her, and she had no obligation to fulfill any order or request. She could not be fired, demoted, or reassigned by him. “I’ve never been employed, I’ve never been paid by the government,” Butina told me, and no evidence of it has ever been presented by the FBI or prosecutors.

It could, in fact, be argued that it was O’Neill and not Torshin for whom Butina was working. He was the one paying her tuition, and she was assisting him with his dinners and events.

Arresting Butina on such grounds set an extremely dangerous precedent. Why couldn’t the Russian government simply return the favor to the United States? Putin, in fact, even seemed to suggest that Butina’s arrest would lead to retribution. “The law of retaliation states, ‘An eye for an eye or a tooth for a tooth,’” he said in a news conference on December 20. On December 28, Russian authorities arrested an American citizen, Paul Nicholas Whelan, a former Marine attending a wedding in Moscow, and charged him with espionage. Like Butina, he had visited the country frequently, exhibited an affinity for it, was involved with guns as a licensed dealer—and is probably innocent. Now facing a possible 20-year prison term in Russia, he was likely arrested simply in retaliation for Butina’s arrest and with the idea of a trade.

Courtroom sketch: Dana Verkoutern/AP Images

Courtroom sketch: Dana Verkoutern/AP Images Prosecutors, faced with a humdrum case involving a grad student, friendship dinners, and little evidence, landed on the idea of sex, with Butina as the Kremlin’s Red Sparrow. “They were interested in sex,” one of the witnesses interviewed by the FBI told me. They “wanted to know if George [O’Neill] had sex with Maria. They couldn’t establish that, but that’s what they wanted.” O’Neill, who’s married with five children, denied the allegation that he’d had an affair with Butina. “That’s ridiculous,” he told me. “Maybe these guys have been watching too much TV.”

The FBI also seemed convinced, the witness said, that Paul Erickson had been seduced as part of what they called Butina’s “honeypot thing.” At Butina’s arraignment, prosecutor Erik Kenerson argued that Butina posed a flight risk, because her relationship with Erickson was “duplicitous” and “simply a necessary aspect of her activities.” His evidence for this claim was that Butina had occasionally complained about Erickson, and also that she had offered another person sex “in exchange for a position within a special interest organization.”

The claim, however, was a false and deliberate “sexist smear,” Butina’s lawyers argued. What the government refused to reveal was that the basis for the accusation that she exchanged sex for access was a three-year-old joke in a text to a longtime friend, a Russian public relations employee at the Right to Bear Arms. Humorously complaining about taking her car for an annual inspection, he wrote, “I don’t know what you owe me for this insurance they put me through the ringer.” Facetiously, Butina replied, “Sex. Thank you very much. I have nothing else at all. Not a nickel to my name.” The friend then wrote back in the same humorous vein that sex with Butina did not interest him. Butina was also a longtime friend of the colleague’s wife and child. Butina’s lawyers pointed out that prosecutors had “deleted sentences, misquoting her messages; truncated conversations, taking them out of context; replaced emoticons with brackets, twisting tone; and mistranslated Russian communications, altering their meaning.”

Yet the prosecution’s suggestion that Butina traded sex for influence worked very well as a publicity tactic. “Who Is Maria Butina? Accused Russian Spy Allegedly Offered Sex for Power,” read the headline in USA Today. CNN carried the breaking news banner, “The Russian Accused of Using Sex, Lies, and Guns to Infiltrate U.S. Politics.” Within days, a simple Google search using the phrase “Maria Butina” and “sex” produced more than 300,000 hits, and she became the butt of jokes on shows like Full Frontal with Samantha Bee.

For Butina, the slander was “just a pure sexist story,” she told me. “I’m still considered to be the source of the money, a honeypot, all this crazy stuff.” The government also accused her, falsely, of using her master’s degree program, where she earned a straight-A average, as a cover to stay in the United States. She was frustrated and disillusioned. “I came here because kids of my generation believed in the U.S., because our laws are based on yours. This is the human rights place. They just smashed my reputation.”

Months later, when Butina’s defense attorneys finally forced the prosecutors to reveal the innocent, underlying messages, Kenerson claimed it was a simple misunderstanding on their part. It was a claim Judge Tanya Chutkan didn’t buy. “It took approximately five minutes for me to review those emails and tell that they were jokes,” she said. Kenerson then asked for and received a gag order so that neither Butina nor her attorney, Robert Driscoll, would be able to talk to the press and tell their side of the story until the end of the trial.

When I asked Frank Figliuzzi, the former head of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, about the prosecution’s conduct, he was angry. “I am troubled and hope there is a full inquiry,” he told me. “This is disturbing. The question is whether this is convenient ineptitude or something far deeper.”

“They manipulated the evidence,” was the opinion of a former assistant U.S. attorney familiar with the Washington, D.C., office. It was a place he had spent many years prosecuting cases. “The government is basically calling her a whore in a public filing.... I think it was an attempt to influence media coverage.” He added, “This seems like somebody panicked, they moved too early, now they’re trying to figure out what to do.”

It is also another example of the media marching in formation with the government, as it did in the lead-up to the war in Iraq. “I think journalism skepticism stops at whatever a prosecutor says,” the former assistant U.S. attorney told me. “If you’re supposed to afflict the powerful, the most powerful people to afflict are the people who have the power to put you in jail. But those are the people reporters are so often most credulous about.”

A senior CIA official who held one of the highest jobs in the agency’s Clandestine Service, and who worked closely with the FBI on many spy cases, offered a cynical view of the bureau’s counterintelligence work. “They want to generate headlines. They don’t care if the information is credible or not,” he said, asking to remain anonymous because of his past clandestine work. “I feel sorry for Butina; she got caught up in this whole vortex. They’re just interested in putting another notch in their belt, and they don’t care who gets hurt in the process.”

Driscoll, Butina’s attorney, is a former deputy assistant attorney general with the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division and has handled political and national security-related cases for decades, but never anything like this. “I wake up periodically at night and think this case is taking place in some alternative reality,” he told me. “A ‘spy’ who uses no tradecraft and posts her every move on social media; a ‘handler’ who travels with and communicates openly with his charge; and a ‘mission’ to somehow undermine the United States by having friendship dinners with Russians and Americans seeking peace.”

On November 23, 2018, Butina went to sleep on a blue mat atop the gray cement bed in her cell, her 81st day in solitary confinement. Hours later, in the middle of the night, she was awakened and marched to a new cell, 2E05, this one with a solid steel door and no food slot, preventing even the slightest communication. No reason was given, but her case had reached a critical point. Prosecutors were hoping to get her to plead guilty rather than go to trial, and had even agreed to drop the major charge against her: acting as an unregistered foreign agent of Russia. Born and raised in Siberia, she is terrified of solitary confinement. Fifteen days later, still in solitary, she signed the agreement, pleading guilty to the lesser charge, one count of conspiracy.

During our interviews before her arrest, Butina told me that she was “a huge fan” of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. “I love the story,” she said. “For some reason it fascinates me. It seems to be simple, but it’s so complicated a story.” Stepping off the plane to begin grad school at the start of the Trump-Russia maelstrom, she, like Alice, began her tumble down the rabbit hole.

No comments :

Post a Comment