Asus's new TUF Gaming laptops use AMD's 2nd Gen APU and Radeon graphics

Asus's new TUF Gaming laptops use AMD's 2nd Gen APU and Radeon graphics AMD updated its Link system monitoring app in December 2018 with new features, and now it's teaching people how to take advantage of them.

AMD updated its Link system monitoring app in December 2018 with new features, and now it's teaching people how to take advantage of them. The government of Abu Dhabi is rumored to look for a buyer for its Global Foundries business. Then news comes months after Global Foundries announced that it was ceasing its investment in the 7nm process generation.

The government of Abu Dhabi is rumored to look for a buyer for its Global Foundries business. Then news comes months after Global Foundries announced that it was ceasing its investment in the 7nm process generation.

Last Friday, less than 24 hours after detailing a bizarre plot by the National Enquirer to extort him with nude photos, Jeff Bezos took some hostages of its own. The newspaper he owns reported that Amazon, which had selected New York City as one of two “winners” of its HQ2 sweepstakes, was “reconsidering” its agreement with Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio to bring 25,000 jobs in exchange for billions in tax breaks and incentives. The alleged reason: mounting opposition from state and local lawmakers and activists in Long Island City, the Queens community where the tech giant planned to build its campus.

On Valentine’s Day, rather than engage with his opponents, Bezos shot the hostages and canceled the deal. De Blasio, despite having courted Amazon, tried to spin this political blow to resonate with the growing backlash against Big Tech:

You have to be tough to make it in New York City. We gave Amazon the opportunity to be a good neighbor and do business in the greatest city in the world. Instead of working with the community, Amazon threw away that opportunity.

— Mayor Bill de Blasio (@NYCMayor) February 14, 2019State Senator Michael Gianaris, one of the fiercest critics of the deal, compared Amazon to a spoiled brat. “Like a petulant child, Amazon insists on getting its way or takes its ball and leaves,” Gianaris said in a statement. “The only thing that happened here is that a community that was going to be profoundly affected by their presence started asking questions.”

But Amazon’s about-face was not a temper tantrum. It was a calculated move to preserve, even enhance, the company’s leverage in trying to extort taxpayer-funded handouts for projects across the country. Amazon is sending the message that it will bend to no city or state government. If any locality tries to cut a better deal—or, god forbid, criticizes the company for its business practices—Amazon will walk away. Bezos is making the cynical, and probably accurate, bet that many desperate communities in America won’t dare to try.

Just a few months ago, it looked as if Amazon had pulled off one of the greatest scams in corporate history. Having dangled 50,000 jobs and $10 billion in investment in a proposed second headquarters in front of every struggling city and municipality in the country, they sat back as lawmakers debased themselves in a race-to-the-bottom to see who could offer the largest set of tax breaks and other incentives. When it came time to decide, Amazon told Detroit and Cleveland to shove off and settled in the two areas that least needed them, New York City and Northern Virginia.

It was the perfect plan—for Amazon. The company collected valuable, often confidential data about infrastructure, educational offerings, and future development plans from areas they would have never considered moving to, which it will use to help perfect its logistics and business strategy. It also got some good PR, at least at first. While some cast the exercise as a capitalist Hunger Games, the HQ2 sweepstakes, as it came to be known, was also a massive marketing ploy, a yearlong corporate Bachelor in which cities wooed the trillion-dollar company. In doing so, it drove up the asking price. The result in New York was nearly $3 billion in tax breaks and a suite of other goodies.

In Virginia, things have mostly worked out for Amazon. Earlier this month, Governor Ralph Northam took a break from embarrassing himself to sign a deal that would provide up to $750 million in incentive cash. But in New York, the HQ2 deal was met with furious resistance. There were protests over the shameful corporate welfare being doled out to one of the most valuable companies in the history of the world, and the impact 50,000 white-collar jobs would have on New York City’s already strained housing and transportation. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the newly sworn-in congresswoman who represents parts of Queens, slammed the “creeping overreach of one of the world’s biggest corporations,” while Senator Kirsten Gillibrand criticized the deal for its “lack of community input and the incentives Amazon received.”

The case being put forward by the deal’s critics was a good one. If Amazon wanted to move to New York City, they could absolutely do so—just without the billions in free money that it absolutely doesn’t need. Amazon brought in $233 billion in revenue in 2018. Bezos is worth $135 billion. And New York City is hardly thirsting for tens of thousands of white-collar jobs. But this was still too much for Amazon, which said in a statement:

“After much thought and deliberation, we’ve decided not to move forward with our plans to build a headquarters for Amazon in Long Island City, Queens. For Amazon, the commitment to build a new headquarters requires positive, collaborative relationships with state and local elected officials who will be supportive over the long-term. While polls show that 70% of New Yorkers support our plans and investment, a number of state and local politicians have made it clear that they oppose our presence and will not work with us to build the type of relationships that are required to go forward with the project we and many others envisioned in Long Island City.”

It’s true that polling suggested that a majority of New York residents approved of the Amazon deal, though it’s unclear if they also approved of the generous subsidies the company would rake in. But Amazon soon realized that the politics of the deal were not in their favor, and that they would face years, perhaps decades, of scrutiny from city and state lawmakers. The deal itself, moreover, would likely become a crucial issue in legislative elections, skewing both the City Council and the state legislature further against Amazon. And with activists bringing negative attention to HQ2’s impact on housing and homelessness and the company’s work with ICE, the deal was clearly becoming a non-starter in America’s media capital.

Amazon still could have renegotiated its deal and won over some of its critics. But to do so would have been to admit that cities can push around one of the world’s most powerful companies. This is not the way that Amazon does business. In Seattle, where it has been headquartered since its inception, the company has been particularly ruthless. Most recently, it threatened to leave Seattle if the city council went forward with a new tax on large corporations aimed at eradicating Seattle’s out-of-control homelessness problem.

Amazon wants to show that even New York, one of the richest cities in the world, isn’t big enough to stand up to it. That’s not the case, clearly. New York can afford to spurn 25,000 jobs. Cleveland or Detroit? Not so much. But that doesn’t necessarily mean Amazon is headed there. For the moment, they have “no plans to re-open the HQ2 search” and may simply add more workers to their Northern Virginia campus, and a development planned for Nashville. Amazon may well claim that New York ruined it for everyone, when in reality what the company is offering is a bad deal for any community, no matter how dire things may be. Only a corporation as large and audacious as Amazon would believe it can take the entire country hostage.

The elastic face of Jake Gyllenhaal is mobile with outrage: “I assess out of adoration. I further the realm I analyze!” The critic for ArtWeb—a thin fictionalization of the ArtNet online fine-art hype machine—Morf Vandewalt has just been accused of feeding tips to a collector before he publishes a positive review. But his protests ring a little hollow, which could spell trouble for him: In Velvet Buzzsaw, the new satire from Dan Gilroy, there are slasher-style consequences for the art world’s sell-outs.

The Instagram-drenched fine-art industry is overdue for a savaging, and there is nobody pure of heart in Velvet Buzzsaw. Josephina (Zawe Ashton) is a beautiful young woman who works for Rhodora (Rene Russo), a beautiful older ex-punk and owner of Haze Gallery (which sounds a lot like New York’s Pace Gallery). Morf and Josephina hook up during a Miami Art Basel trip before returning to Los Angeles. Once back, Josephina discovers her upstairs neighbor dead. Ventril Dease is his name, and he has left behind an apartment full of paintings, with specific instructions that they be destroyed.

The paintings exert a strange effect on all who see them. Dease seems based on Henry Darger, the janitor who died leaving behind an apartment full of eerie illustrations of little girls in a magical land, and a 15,0000-page fantasy novel. Like Darger, Dease made rather violent figurative paintings, but his are dressed up in oil brushstrokes.

Josephina sees their value at once, and ignores Dease’s request to destroy the work. The work is a hit. A gallerist-turned-art adviser named Gretchen (Toni Collette in sharp form) snaps a whole lot of it up. Although the art restorer’s lab finds something unpleasant mixed into Dease’s paint, the buyers love him. Morf loves him, too, and, faced with the canvases, announces that “critique is so limiting and emotionally draining.” Instead, he announces, he’ll write a book.

The murderous spirit of Ventril Dease, unfortunately, appears to inhabit his works. One by one, the movie’s key players are picked off by violent “accidents” that take place when they’re near art. A rude handler reaches a sticky end while next to a tacky gas station print of some dogs. Somebody else gets their arm eaten by an expensive sculpture. It’s all very schlocky, a little ‘80s, and extremely fun.

The criteria for suffering supernatural death seems to be simple: If you have profited off the artwork of Ventril Dease, which was never supposed to be exhibited, then you’re in for it. That seems a straightforward critique, on first glance: Commerce destroys the spirit of art, and in this case the art is out for revenge. But the form that the violence takes suggests a more interesting and complex theme. You always know that a death is about to happen when some nearby object—a doll, a painted face—starts glowing out of its eyes. And the art that kills people is uniformly bad: graffiti canvases, a stupid installation, an overpriced objet.

Gyllenhaal’s Morf is a ridiculous figure. He’s rich beyond all reason for a critic, and likes to do ostentatiously transgressive things like write naked and get very, very close to the art he is appraising. He’s also a dreadful writer. Dease was “using the art to dive deep into his own psyche.” He calls another exhibition a “snoozefest.” (In an interview, Gyllenhaal has said that he based the character on New York’s Jerry Saltz.) As Morf’s mind starts to disintegrate in the wake of Dease’s killings from beyond the grave, the celebrated critic visits an optician, because he has started “seeing things.” Josephina accuses him of “losing his eye.”

So when those horrible little eyeballs start glowing, you know that a bad artwork is about to fight back against the over-privileged human eye of the critic. Graffiti paint creeps up the body of a woman who hates graffiti, ruining her minimal aesthetic; a Brancusi-like bronze tries to crush a woman who has just gotten too rich. It’s as if every painting or sculpture deemed unworthy or otherwise abused by the industry (exploited for quick cash, say, or insulted) is revolting against their overlords. The critic is the last one they’ll chase, and the most significant.

As Josephina puts it in a key line, “What’s the point of art if nobody sees it?” Morf’s “eye” has been imbued with too much power, which has upset the balance between artwork and viewer. In between the glamorous silliness of the Basel scenes and Morf’s bespectacled antics, director Dan Gilroy appears to be making a kind of John Berger-style argument about the way we relate to visual culture. In his famous TV series Ways of Seeing, Berger posited that premodern art often presented objects on canvases (food, women, landscapes) as a kind of subservient offering to the viewer-patron. In the twentieth century, he said, the artwork retained its status as a luxury object, but became newly swaddled in the “false mystifications” of concepts so inaccessible and mysterious that they required an interpreter. “What may become part of our language,” Berger said, “is jealously guarded and kept within the narrow preserves of the art expert.”

Each of Gilroy’s films (Velvet Buzzsaw, Nightcrawler, and Roman J. Israel, Esq.) have pursued a remarkably coherent theme—the effect of money on the human soul. In Roman J. Israel, Esq., an idealistic lawyer loses his moral compass at the prospect of reward money. In Nightcrawler, Louis Bloom (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a stringer who chases gruesome crime stories for a living. In both these movies as in Velvet Buzzsaw, Gilroy focuses on a male antihero, entrenched in some particular subculture, as the spider in the middle of a web of human relationships that are all compromised by a group failure of conscience.

Velvet Buzzsaw has none of the self-seriousness of Nightcrawler, which is to Gilroy’s credit. It’s impossible not to enjoy Toni Collette’s lampooning of an overpaid tastemaker; people in art are often just as snobby and absurd as the movie makes out. In that sense, it’s realistic. But Gilroy’s sociocultural analysis falls a bit flat. The movie does not really distinguish between stupid art and interesting art, instead lumping all visual culture together as a bloc against which art people can show their true colors. I also wish to God that critics were as rich or powerful as Morf Vanderwalt—that misrepresentation rather throws Velvet Buzzsaw’s critique off-base, too.

Still, the movie is undeniably fun. It comes within an inch of a really snappy disquisition (to use Morf’s word) on the painting marketplace, but to avoid disappointment it’s better approached as a gory romp. In John Berger’s words, “Glamor cannot exist without personal social envy being a common and widespread emotion”—and we love to see the glamorous punished.

It was not so long ago that Donald Trump and Marco Rubio were bitter enemies. During the 2016 primary, Rubio called Trump a “con man” and suggested that he had wet his pants during a debate. In return, Trump dubbed the Florida senator “Liddle Marco,” questioned the Cuban-American’s citizenship, and mocked his 2013 response to Barack Obama’s State of the Union address, in which he had to interrupt his televised speech to chug a very small bottle of water. “‘I need water. Help me,’” Trump croaked in a campaign speech mimicking Rubio, before calling him a “choke artist.”

Rubio is hardly the first Republican critic of Trump to do a grinning about-face once Trump secured the presidential nomination and went on to win the election. But more than most opportunists on Capitol Hill, Rubio has used the Trump presidency to elevate his stature and amass power. To an unprecedented degree for a lawmaker, he is directing the government’s approach to an entire region: Latin America. It’s a part of the world that has long been subject to the whims of U.S. foreign policy—now, those whims increasingly belong to one man.

Consider that, until recently, the Trump administration showed deep apathy toward Latin America. While Barack Obama and George W. Bush had each made a handful of trips to the region by this point in their first terms, Trump did not travel to Latin America until November, to the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires. Last year, he canceled trips to Lima and Bogotá, and he has yet to visit Mexico, sending his daughter Ivanka Trump to the December inauguration of Mexico’s new president in his place. Eleven out of 28 diplomatic posts in Latin America and the Caribbean remain empty. An assistant secretary of state for Latin America was not finalized until October, nearly two years into Trump’s first term.

But indifference turned to enthusiasm on January 23, when in a rebuke to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, Trump recognized a 35-year-old right-wing upstart named Juan Guaidó as the country’s legitimate leader, a move that The Wall Street Journal described as the “first shot in [a] plan to reshape Latin America.” The force behind the Trump administration’s move was Rubio. In the absence of a clear policy for the region, The New York Times has called Rubio “a virtual secretary of state for Latin America.” On Cuba policy, to name one egregious example, Trump reportedly has offered his National Security Council little guidance but to “make Rubio happy.”

The son of Cuban émigrés who cemented his personal and political identity around antagonism toward the Castros, Rubio has hounded Trump to take a hardline stance against the so-called “troika of tyranny”: Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua. This agenda includes ousting Maduro from the presidential palace in Caracas, lifting the Obama-era detente with Havana, and supporting the popular movement against Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and his leftist Sandinista Party in Managua.

But his agenda doesn’t stop there. Recent moves suggest that Rubio has his eyes on the total reversal of the so-called Pink Tide of left-leaning governments that dominated Latin American politics in the early 2000s. And he’s just getting started.

For Trump, pleasing Rubio and his Miami base—a stronghold of conservative Latino voters—is key to a 2020 victory in the battleground state of Florida, where he beat Hillary Clinton by a mere 113,000 votes in 2016. Florida is home to some 1.2 million Cubans and 190,000 Venezuelans. “Trump doesn’t care about Latin America. It’s all about domestic politics,” said William LeoGrande, an expert in U.S.-Latin American relations at American University. “Trump thinks he won Florida because of the Cuban American vote. Rubio convinced him that that’s what made the big difference in Florida.”

Rubio’s influence over Latin American policy is highly unusual for a senator. While Cuban-American members of Congress have long held outsized clout when it comes to foreign policy toward Cuba, Rubio’s reach extends further afield, in particular to Venezuela, which has served as a close ally and economic lifeline to Cuba for decades. On January 22, Rubio—flanked by Florida Governor Rick Scott and Florida Representative Mario Diaz-Balart, a fellow Cuban-American from Miami—went to the White House to call on Trump to support Juan Guaidó and the Venezuelan opposition. The next day the Florida politicians got their wish. The United States, followed by 20 other countries, recognized Guaidó as interim president.

“I can’t think of another moment when such a crucial aspect of foreign policy was outsourced to a senator on such a critical decision as to recognize a dissident as the president of a country,” said Greg Grandin, author of Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and Rise of New Imperialism and a professor of history at New York University. “It’s pretty audacious and it’s pretty unusual.”

“All signs suggest that Rubio has assumed an increasingly prominent role in shaping conversations in and out of the White House about U.S. policy toward Latin America,” said Michael Bustamante, a professor of Latin American history at Florida International University in Miami. “The question that’s on everybody’s mind is whether Venezuela is the first step, and if they’ll move onto Cuba as the next target.”

From an early age, Rubio admired the politics of first-generation Cubans who crossed the Straits of Florida on shrimp fishing boats and wooden rafts in 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. He began his career working with staunchly pro-embargo politicians, like Cuban-born Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen from Miami. Because of his old-school conservative politics and boyish looks, some Spanish-language media outlets have described Rubio as un joven viejo—a young fogey. “Rubio is very much a product of West Miami politics, a small, mostly blue-collar, reliably Republican municipality in the greater Miami area,” said Ricardo Herrero, who directs Cuba Study Group, a pro-engagement organization of Cuban-American business leaders.

As a voting bloc, Cuban exiles in Miami have formed a near-unified stance against the Cuban government and in support for the embargo, in the hopes that it will one day bring down the Communist Party. “Miami has often been a place where those who find themselves in the crosshairs of left-leaning Latin American governments end up,” said Michael Bustamante, a professor of Cuban history at Florida International University in Miami. “There’s a long tradition in the Cuban exile community of seeing like-minded left-leaning governments in the hemisphere, particularly those that are closest to Havana, as enemies.”

While many second- and third-generation Cuban-Americans identify as Democrats and support an end to the embargo on Cuba, their parents, especially elites who lost property or had family members imprisoned during Cuban Revolution, remain steadfast in their hardline stance, which extends to Venezuela. “The triumph of the Castro Revolution in 1959 dispersed a lot of right-wing elements into the United States and injected the right with a new kind of constituency, Cuban émigrés,” said Grandin, the professor of Latin American history at NYU. Today 67 percent of Cuban Americans in Miami between ages 60 and 75 support the embargo, while only 35 percent of Cuban adults under age 40 do, according to the Florida International University’s 2018 Cuba Poll. “[West Miami] is one of the few pockets here where taking a hardline stand against Cuba still yields electoral rewards,” said Herrero. “And Venezuela is really an extension of the position on Cuba.”

Meanwhile, fifteen miles west of Miami, the affluent city of Doral, Florida—which some call “Doralzuela” for its growing population of Venezuelan exiles—is a hub of support for U.S.-backed regime change in Venezuela. In Doral, it’s common to see Venezuelan flags and bumper stickers with the message “Pray for Venezuela.” On February 1, Vice President Mike Pence, a close ally of Rubio’s, traveled to Doral to speak to Venezuelans about ending Maduro’s rule. “This is no time for dialogue,” said Pence to a cheering crowd of Venezuelan exiles at a church. “It is time to end the Maduro regime.”

Since August 2017, when news broke that a powerful lawyer in Caracas had plotted an assassination attempt on Rubio, the Florida senator says he has talked to Trump at least once a month about Venezuela. He has reminded him of the payoffs in Florida in 2020 for supporting regime change: “There could be electoral rewards,” Rubio recently told the Associated Press.

“[Rubio] has been relentless ... working hard to earn the president’s trust in this policy area,” former Representative Carlos Curbelo, a Florida Republican, told The New York Times. “He owns it and it has clearly paid dividends for him.”

In order to win Florida in 2020 and by extension a second term in the White House, Trump must turn out Cuban and Venezuelan voters. In the 2018 midterms, only 31 percent of Latino voters in Miami cast ballots for Democratic candidates. Older Cuban-Americans tend to vote for politicians with the most conservative stances on relations with Cuba and Venezuela. “Foreign policy is domestic policy in South Florida,” Democratic Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who lives in south Florida, recently said.

Aside from short-term electoral gains, Trump himself appears to care little about what happens in Latin America. That is not the case for Rubio. After taking office in 2017, Trump payed lip service to Cuban-American voters by taking rhetorical rather than substantive steps to roll back relations with Cuba. U.S. businesses with investments in Cuba wanted to keep the relationship open, and Trump understood this. (At one point, Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts scouted land in Havana.) But Rubio was not satisfied. In recent months, he has pressured the White House to put Cuba back on an international terrorism list, impose sanctions on Cuban officials, and end U.S. travel and academic exchanges to the island. Last year, at Rubio’s urging, the United States withdrew most of its diplomats from Cuba. The real feather in his cap will be if the Maduro government falls in Venezuela, which could have devastating effects on Cuba, since it relies on subsidized oil from Venezuela.

With Trump bowing to his wishes, Rubio has also started exerting his influence on other Pink Tide countries. Starting in 1999 with Hugo Chavez’s ascent to power in Venezuela, there was a leftward turn in Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Uruguay, Honduras, and Ecuador. Until a right-wing lurch in the mid-2010s, these governments rode a commodities boom, increasing public welfare spending and lowering Latin America’s poverty rate from 45 to 25 percent between 2000 and 2014.

In 2019 only a few leftist governments remain. Rubio’s agenda has disquieting parallels to the Cold War years when the United States supported the removal of governments in eight countries across the region, ushering in a wave of dictators in their stead. Despite Rubio’s opposition to socialist governments on the grounds of human rights violations, he has praised authoritarian right-wing leaders, such as Brazil’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro, a military strongman who has extolled dictatorship, joked about raping women and killing civilians, and called for the wide-scale deforestation of the Amazon. In January Rubio penned an op-ed for CNN.com with the headline “U.S. Should Go Big on Brazil.”

Over the past year, Rubio has directed U.S. policy on a range of smaller issues affecting the region. In May, in his role on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he suspended funding for Guatemala’s anti-corruption commission, CICIG, which was investigating right-wing President Jimmy Morales, his sons, and his brother on accounts of fraud and corruption. In October, he handpicked Mauricio Claver-Carone, a prominent contributor at the conservative blog Capitol Hill Cubans and a pro-embargo lobbyist, to lead the department of Western Hemisphere affairs at the National Security Council. In August, he boasted on Twitter about drafting legislation to cut off aid to El Salvador for moving its embassy from Taiwan to China. On February 6, Foreign Policy reported that Rubio convinced the Trump administration to abandon its nomination of career diplomat Francisco “Paco” Palmieri as ambassador to Honduras, insisting that his politics were not hardline enough. On February 8, Rubio condemned Mexico for continuing to recognize Maduro as president of Venezuela.

These activities paint a picture of Rubio’s vision for Latin America—a return to Cold War policy. There’s a long history of the U.S. meddling in Latin American affairs to assert U.S. hegemony, and it tells us that what comes next could be bloody and ultimately transformational for the region. How far Rubio is able to push his agenda hinges, most pressingly, on his success in Venezuela.

One evening last summer, Chike Ukaegbu, a 35-year-old New York tech entrepreneur, called his uncle, Augustine Akalonu: “Are you sitting down?” Ukaegbu asked. Dr. Akalonu was sitting down; he was driving home from his pediatrics practice in the Bronx. Ukaegbu had just been named among the global 100 most influential people of African descent under forty. He had been speaking at conferences around the country and running a lauded tech accelerator in New York. But he wasn’t calling about any of that.

“I’m going to run for president,” Ukaegbu said, a characteristic note of mischief in his voice.

Dr. Akalonu, a jovial man in his mid-sixties with an easy, unhurried manner said, “Great. President of what?”

“Of Nigeria,” replied Ukaegbu.

“I nearly had a car accident,” Dr. Akalonu told me a few months later in November, at a fundraiser he hosted in Nyack, New York. Ukaegbu had become the youngest presidential candidate in Nigerian history.

“Gerontocracy.” That’s the word critics use to describe Nigerian politics. The country has a population of almost 200 million—the largest on the continent, and the youngest: Sixty percent of Nigerians are under age 30, only six percent are older than 60. But government leadership positions are overwhelmingly filled by the aged. This disparity illustrates a broader African trend. In 2017 researchers estimated the median age of the continent’s population was 20, while the average age of a head of state was 62. In May 2018, however, a month after angering Nigerian youth with disparaging comments at an event in London, President Muhammadu Buhari, 75, signed a law lowering the minimum age for presidential candidates from 40 to 35.

Ukaegbu came to the U.S. in 2002 at the age of 19 to study biomedical engineering at the City College of New York. That’s where I first encountered him, although we were not friends and moved in different circles. “I don’t remember all students who participated in our program, but I do remember him,” Nora Heaphy, then a program director for the college’s Colin Powell Fellows in Leadership and Public Service, told me. “He was extremely charismatic, very open to learning, very engaging.” While many fellows went to entry-level jobs at D.C. think tanks upon graduation, she said, Ukaegbu stayed in New York. In 2010, he and a friend he had met at a church concert, Kevaughn Isaacs, launched a non-profit called Re:LIFE, training disconnected youth in Harlem and Washington Heights to develop business plans and helping them complete their education. Ukaegbu himself enrolled in distance learning courses in business management and venture capitalism at Cornell, the University of Pennsylvania, and Stanford, as his plans expanded.

In 2013, Re:LIFE ran its first startup class requiring each trainee to launch a business by the program’s end, and Ukaegbu began noticing what he saw as bias. “I saw several brilliant founders who were not getting funded,” he told me. “And I heard several bullshit stories from investors explaining why they’re not funding these people.” In 2015, he founded Startup52, a Manhattan-based “start-up accelerator” aiming to offer young entrepreneurs from underrepresented demographics intensive coaching in polishing their business plans and investor pitches. Two years later, the accolades for Re:LIFE and Startup52 helped him receive a green card through the United States’ National Interest Waiver category.

“This is the new Nigerian dream,” Damilare Ogunleye, Ukaegbu’s 33-year-old Lagos-based campaign director, told me when we met in Lagos in January. “To leave, embed in the system in the U.S., U.K., or wherever, and skip all the problems of Nigeria.”

Chike Ukaegbu and his brother Chibueze Ukaegbu Jr. (left), in the campaign office in Abuja in January. Photographs by Pawel Slabiak

Chike Ukaegbu and his brother Chibueze Ukaegbu Jr. (left), in the campaign office in Abuja in January. Photographs by Pawel SlabiakNigerian politics, with its volatile mix of money, violence, and humor, is often surreal. Out of more than 70 candidates who initially declared intent to stand in the presidential election on February 16, 2019, only two have emerged as frontrunners. One is current president Buhari, who due to months’-long medical leaves in the U.K. has had to publicly deny rumors that he has died and been replaced by his double, a hypothetical Sudanese named Jubril. “It’s the real me,” Buhari assured an audience of Nigerian expatriates at a U.N. climate summit in Poland in December. Despite Transparency International placing Nigeria 148th out of 180 countries on a corruption index last year, with scores virtually unchanged during a four-year presidency premised on fighting corruption, Buhari has titled his reelection manifesto Next Level, unironically vowing even greater progress.

Buhari’s chief rival is Atiku Abubakar, a 72-year-old businessman who has been unable to travel to the U.S. since 2005, when an American investigation implicated him in a transatlantic bribery case involving an FBI sting, a telecommunications deal, and $90,000 stashed in a Louisiana congressman’s freezer. Abubakar finally managed a visit to Washington, D.C. in January, reportedly helped by Brian Ballard, a lobbyist with extensive links to the Trump administration. In Nigeria, Abubakar has faced numerous corruption allegations.

“The surest way to riches and power,” former U.S. ambassador Joseph Campbell and Chatham House fellow Matthew Page wrote of Nigeria in 2018, “is through elected office and the opportunities for kleptocratic state capture that it offers.” Successful candidates today are often “godfathered” by prior office holders who have amassed great wealth from public funds, bankrolling party and campaign costs in exchange for a continued cut of national treasure once the sponsored candidate assumes office. Political parties resemble businesses, low on ideology or policy objectives, funded top-down by the godfather, the top office holder, or, during campaigns, by the candidate for highest office.

Ukaegbu’s eccentric campaign began with a chance encounter at a Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies event last April. Ogunleye, who worked on political campaigns while at a Nigerian communications firm from 2012 to 2015, was visiting with a delegation of Lagosian entrepreneurs—he currently runs a T-shirt and mug customization website called Suvenia.com. The two men bonded over a passion for tech innovation: Ukaegbu had been reaching out to Nigerian officials and one presidential candidate with a technology blueprint for the country, a platform politicians could adopt and promote, with no response. “You should run,” Ogunleye told him.

In June, Ukaegbu began holding daily videoconferences from New York with a core team: his older brother Chibueze, who runs a coding academy and software firm in Aba; Ogunleye in Lagos; and a banker in Abuja. The four began planning how to introduce Ukaegbu to voters, raise funds, and obtain a political party nomination, as required by law. They found inspiration, Ogunleye told me, in an Old Testament anecdote in which four lepers, rather than starve in a city besieged by the Syrian army, set out for the Syrian camp, hoping for nourishment or swift death. When they arrive, they find it full of provisions but abandoned: The Syrians heard the thunder of charging chariots and fled in haste. “How do you with four lepers create the sound of chariots?” asked Ogunleye, the sleeves of his suit pinned with card cufflinks featuring the ace of diamonds and ace of spades. “Lead with the media.”

Nigerian news media didn’t bite, but through a contact in D.C. Ukaegbu landed interviews on CNN, BBC, and Al Jazeera. “Everyone got interested,” said Ogunleye. “Who is this guy who is on all these global platforms? What kind of backing does he have?”

In August, after 16 years in New York, Ukaegbu moved back to Nigeria to launch his campaign. Other parties showed up to offer him office nominations and cabinet positions with them—a standard tactic to neutralize political opponents. During one meeting Ogunleye found particularly gratifying, a consultant from Atiku Abubakar’s People’s Democratic Party, eager to demonstrate that the unknown Ukaegbu stood no chance, tapped a bystander. “Do you know this guy?” she asked. The man squinted. “Don’t force yourself,” said the consultant. But the man kept looking at Ukeagbu. “Hey, aren’t you the guy on CNN?” he said. “You’re good.”

At this point, the scrappy #Chike4Nigeria team included Re:LIFE cofounder Isaacs, now a New York high-school teacher of graphic design and photography, producing all campaign graphics during early morning hours and school recess. Ukaegbu’s older brother, Chibueze Ukaegbu Jr., CEO of a coding academy and software firm named LearnFactory Nigeria, contributed personal funds to the campaign’s shoestring budget and directed efforts of his eight full-time and four part-time staffers to building websites, apps, and WhatsApp broadcasts. In New York, Ezinne Kwubiri, head of inclusion and diversity at H&M, worked her contacts to generate media coverage and organize fundraisers, in addition to helping Ukaegbu manage his increasingly chaotic calendar.

By fall, which is when I came across the campaign on social media, Ukaegbu had become the nominee of the new Advanced Allied Party (AAP). AAP chose Safiya Ibrahim Ogoh, a woman from the country’s predominantly Muslim north, as his running mate—balancing out Ukaegbu’s roots in the mostly Christian south.

Election posters cover walls and fences in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. Tens of thousands of candidates are running for office across all government levels in 2019—more candidates than ever before, according to Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission.

Election posters cover walls and fences in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. Tens of thousands of candidates are running for office across all government levels in 2019—more candidates than ever before, according to Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission.Ukeagbu’s campaign message is that Nigeria stands at a pivotal point in its trajectory—young, rich in resources, and full of ingenuity, but also undereducated, plagued by conflict and corruption, and underdeveloped. Without leaders committed to aggressive investment in education and technology, he and Ogunleye believe, Nigerians will be crushed by the impending fourth industrial revolution—a revolution Ogunleye perceived signs of in China while on an Alibaba fellowship in 2017. “You think it’s bad now?” Ukaegbu asked a crowd in Philadelphia in November. “Just wait for artificial intelligence,” he said. “That will be real hunger games.”

While not all experts may share Ukaegbu’s and Ogunleye’s tech focus, many would agree that Nigeria is in trouble. In a 2019 analysis, Eurasia Group ranks the Nigerian presidential race among this year’s top ten geopolitical risks, thanks to three probable electoral outcomes: Buhari wins (“an elderly, infirm leader who lacks the energy, creativity, or political savvy to move the needle on Nigeria’s most intractable problems”), Abubakar wins (“another gerontocrat who would focus on enriching himself and his cronies”) or no clear winner emerges (“a dangerous wildcard”). Meanwhile, relentless demographic growth continues. In a 2018 report on “Severely Off-Track Countries,” Brookings projects that by 2030 the number of extremely poor in the nation may reach 160 million.

“Wake up!” says Ukaegbu in one of his campaign videos. “We’re in a fight for our lives, and we don’t even know it.”

One searingly hot day in January, I watched Ukaegbu deliver this message to a group of kids and teachers at a private school in Abuja, in the shade of a mango tree. Ukaegbu introduced himself to each person and remembered their names at question time. Despite his dire warnings, he radiated enthusiasm for what he called “amazing Nigeria.” Ben Dike, a teacher at the school who later invited Ukaegbu to teach a fifth-grade math lesson, asked, “How do you intend to compete with these gladiators?”

Realistically, Ukaegbu doesn’t stand a chance in the upcoming election. (“Who’s that?” asked my driver in Lagos when I told him whom I’d come to cover—a dampening response I had heard more than once.) It doesn’t seem to bother him. Ukaegbu “doesn’t see ceilings,” his cousin Ezemdi Akalonu, a junior at Brown University, told me. His family knows him as a 17-year-old who ran away from home to attend Lagos University instead of the local college prescribed by his parents—enraging his mother, a school principal, and his father, a civil servant and entrepreneur—before looking further afield, to the United States. Now, he’s the local boy made good: His high school in Aba invites him back to speak whenever he visits.

Chike Ukaegbu visits a private school in Abuja on January 18th, 2019.

Chike Ukaegbu visits a private school in Abuja on January 18th, 2019.Following the speech at the Abuja school, Ukaegbu and his brother Chibueze decamped to a spartan mezzanine room in a mostly vacant office building. An enormous desk in the otherwise empty, low-ceilinged space, and a bizarrely miniature bathroom gave the room an Alice-in-Wonderland vibe. Chibueze peered into his laptop, working on a website that would allow voters to find young candidates by district. Chike monitored some of the two dozen WhatsApp channels that he said bombard him with “five thousand messages a day.” The lights went off, as frequently happens, until a generator kicked in, and a fan resumed noisily circulating tropical air.

“We’re on the list,” Ukaegbu said, scanning a copy of the roster of presidential candidates, just released by Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission. It was a relief—backroom intrigue and string-pulling, whether from within his own party or elsewhere, could no longer prevent his name from appearing on the ballot.

Despite the early buzz, Ukaegbu’s run has struggled to attract donors. The party, which expected Ukaegbu to bring in the money, is not happy about it. The #Chike4Nigeria team predicted enthusiastic donations from the highly educated diaspora, which remitted home $25 billion in 2018, World Bank data show. According to numbers published by the Center for Social Justice, one tenth of one percent of that sum would match the total for media expenditures made in the 2015 campaign by PDP, the biggest spender and, as the then-governing party with a sitting president, an entity with unrivaled, direct, and unscrutinized access to the country’s oil revenue. But the money hasn’t materialized.

The team has also encountered skepticism from the very Nigerian demographic it hoped would welcome Ukaegbu’s bid: the 18-to-35-year-old voters who make up more than half the electorate. Instead, the most excited supporters have often been retirees, people in their sixties and older.

It’s hard to know how much of that is about the Ukaegbu campaign, and how much of it is about the realities of Nigerian politics. When I asked Matthew Page whether he could imagine an outsider, even a well-resourced one, mounting a successful presidential bid without established patronage-client relationships, he seemed unconvinced. “I think we’re a few decades away from that,” he said.

As I was boarding a flight back to New York in late January, Ukaegbu called me. He sounded tired. For days he had been trying to connect me with his vice-presidential pick, but she kept demurring. Two nights before, at a tense party meeting in a Stygian room in Abuja, I had watched him square off against members who wanted to declare support for Buhari and catch the last trickle of cash from the dwindling stream of the ruling party’s electoral funds. I asked whether he felt discouraged. He said he did not. “It’s certainly been an education,” he told me on the call. “It’s been like a PhD in Nigerian politics.”

New York, NY—(February 14, 2019)—The New Republic today published its March 2019 issue, with a cover package titled “The Battle for Silicon Valley’s Soul.” The five articles, respectively by Ben Tarnoff and Moira Weigel, Kate Losse, Alex Press, Laura Adler, and Sam Adler-Bell, examine the wave of organizing and activism that has galvanized workers in the tech industry over the past year. Whether speaking out against tech’s intimacy with the military or demanding the implementation of new human resource policies to address sexual harassment, employees demonstrating a principled commitment to holding their CEOs accountable.

In “Next Gen,” Ben Tarnoff and Moira Weigel question whether Silicon Valley is growing away from its liberal and libertarian origins. The new generation of employees at companies like Google and Amazon have strayed from the “Californian Ideology” of their bosses. Instead, as Tarnoff and Weigel explain, “they are embracing a more collective, worker-driven politics—one that owes less to Ayn Rand than it does to Eugene Debs.”

“What’s in an Aim?” discusses how tech workers are using corporate mission statements to hold their CEOs accountable. Kate Losse points out that many tech executives have learned over the past year “that a mission statement only commands loyalty when employees believe it is being consistently upheld; that when they see that it isn’t, they will use it as reason to foment dissent, to strike, to leave.”

In “An Unholy Alliance,” Alex Press reviews the ongoing relationship between tech firms and the military, which dates back to the earliest days of computers. “It is hard not to feel that tech’s complicity with the military is too deep to be undone,” Press acknowledges—“the ties too strong to be broken.” However, as employees hold meetings, call protests, and form internal networks, they are building momentum to challenge the long-running intimacy between tech and the Defense Department.

Laura Adler describes how Google’s HR department reckons with #MeToo in “After the Walkout.” After more than a fifth of Google’s global workforce exited their offices (20,000 people in all), to protest how the company handled Andy Rubin’s sexual harassment case, corporations like Google have attempted to appease their employees by implementing old-fashioned human resource policies, which stem from the bureaucratic tool kit tech companies once rejected. However, Alder argues, “Policies like the ones Google is putting in place may be ineffective at best, and at worst may entrench gender inequality.”

In “Choreographing

the Whirlwind,” Sam Adler-Bell

examines how twelve young activists forced a bold idea into the mainstream of

the Democratic Party. Adler-Bell studied the strategy of grassroots climate

organization, Sunrise Movement, and found that the leaders were able to garner

such widespread support once they shifted the focus of their organization away

from structure and, instead, towards the moment of the “whirlwind.” This term,

which was coined by the organizer Nick von Hoffman, “evokes something essential

and visceral about what it feels like to be involved in a wave of political

upheaval. The whirlwind disorients, defies gravity, upends things and leaves

them in a new place.”

Additional

information about the March issue is included below.

[FEATURES]

In

“Passive Resistance,” Mychal Denzel Smith analyzes the Resistance, the ubiquitous term for

all manner of anti-Trump activity and emotion, and questions whether it is really

a movement at all, or simply a form of branding for the most benign type of

opposition. As Smith explains, “While there has been opposition to the most

odious parts of [Trump’s] political agenda, what has truly animated the

Resistance is disdain for Trump’s character.” If the Resistance is to show

itself as a true movement, one worthy of the name it carries and more

meaningful to the people who are participating, Smith argues, “it needs to find

a definition and purpose beyond Trump.”

Over the course of a number of exclusive

interviews with Maria Butina, before and after her arrest, as well as with Paul

Erickson and George O’Neill, James Bamford

explores the case against Butina—and why that case may be crumbling before our

eyes. In “The Spy Who Wasn’t,”

Bamford, who made waves with his exclusive 2014 interview with Edward Snowden,

chronicles the story of how the young Russian gun rights enthusiast may have

fallen victim to prosecutorial overreach on a grand scale. “Without evidence of

espionage, money laundering, passing cash to the Trump campaign, violating

Russian sanctions, or any other crime,” Bamford reports, prosecutors have

fallen back on “rarely used” McCarthy-era espionage legislation to prosecute

Butina.

In “The

Crime of Parenting While Poor,” Kathryn

Joyce acknowledges that the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS),

New York City’s child welfare agency, has a reputation for unjustly targeting

low-income families of color, and wonders whether it has any chance of changing.

While ACS has executed new initiatives through pilot programs that could have a

far-reaching impact on how child welfare is protected, Joyce claims that in order

for government policies to change, society must undergo a transformation in how

it thinks about the problem: it must give up the “Social Darwinist conviction

that the wealthy are most deserving because they are wealthy, and the only

reason poor people are poor is because of some personal flaw.”

[BOOKS & THE ARTS]

In “Off the Map”, Patrick Iber details how the United States reinvented empire. Iber critiques Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, a book that will arrive as perhaps the most hotly anticipated release in American diplomatic history in some time, in part because of an unusual professional dispute between the author and historian Paul Kramer. Iber believes the book “succeeds in its core goal: to recast American history as a history of the ‘Greater United States.’”

Brian Goldstone discusses how Édouard Louis confronts the French elite’s contempt for the poor in “The Dispossessed.” A commentary on the French writer’s new book, Who Killed My Father, Goldstone’s piece examines the shame that pervades Louis’ work. “Now he wants to collect this shame and direct it at its proper targets: those responsible for decades of callous and crushing policy,” says Goldstone. He goes on to note, “It quickly becomes clear, however, that the new book has a force and immediacy all its own. Who Killed My Father tells the story—part lament, part searing polemic—of a tough guy reduced to something like a state of living death.”

“Meat Tech,” by Rachel Riederer, looks at a plan to eliminate animal farming that relies on science and startups in Jacy Reese’s The End of Animal Farming. Riederer notes, “In the literature of meat-eating ethics, Reese has carved out his own niche: the business-friendly techno-utopian optimist.” She continues, “Reese’s idea—that people will give up something pleasurable and familiar without the spark of something deeply felt, be it shame or compassion—relies on a very generous view of the human animal.”

Which political order would give us the most control over our lives? That’s the question Jedediah Britton-Purdy poses in “Free Time,” a review of Martin Hägglund’s book This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. “Hägglund, who teaches literature at Yale, aims to give fresh philosophical and political vitality to a longstanding question,” Britton-Purdy observes. “He argues that to live well requires two things: We need to face our choices with clarity, and we need the power to make choices that matter.”

In “Counterfactuals”, Rachel Syme examines Documentary Now! and how the show, which is entering its third season on IFC, lays bare the pretensions of beloved documentary films. Syme writes, “Making a documentary can be an act of intrusion and manipulation as much as it can be an act of responsibility and care, and Documentary Now! investigates just how thin that line can be.”

Lidija Haas examines Asghar Farhadi’s brilliant orchestration of social dynamics in “Things Fall Apart,” a commentary on the Iranian director’s latest film, Everybody Knows (Todos lo saben). In what is only Farhadi’s second project based outside of Iran, Haas notes that Everybody Knows (starring Penélope Cruz, Carla Campra, Ricardo Darín, Javier Bardem and Bárbara Lennie), takes its drama from the delicate dance of what characters perceive, or don’t, at different moments.

Poems by Timothy Donnelly, Jane Hirshfield and Kathleen Winter are featured this month. For Res Publica, Editor-in-Chief Win McCormack examines The New Republic’s intellectual roots in “Two Traditions.”

The entire March 2019 issue of The New Republic is available on newsstands and via digital subscription now.

For additional information, please contact newrepublic@high10media.com.

###

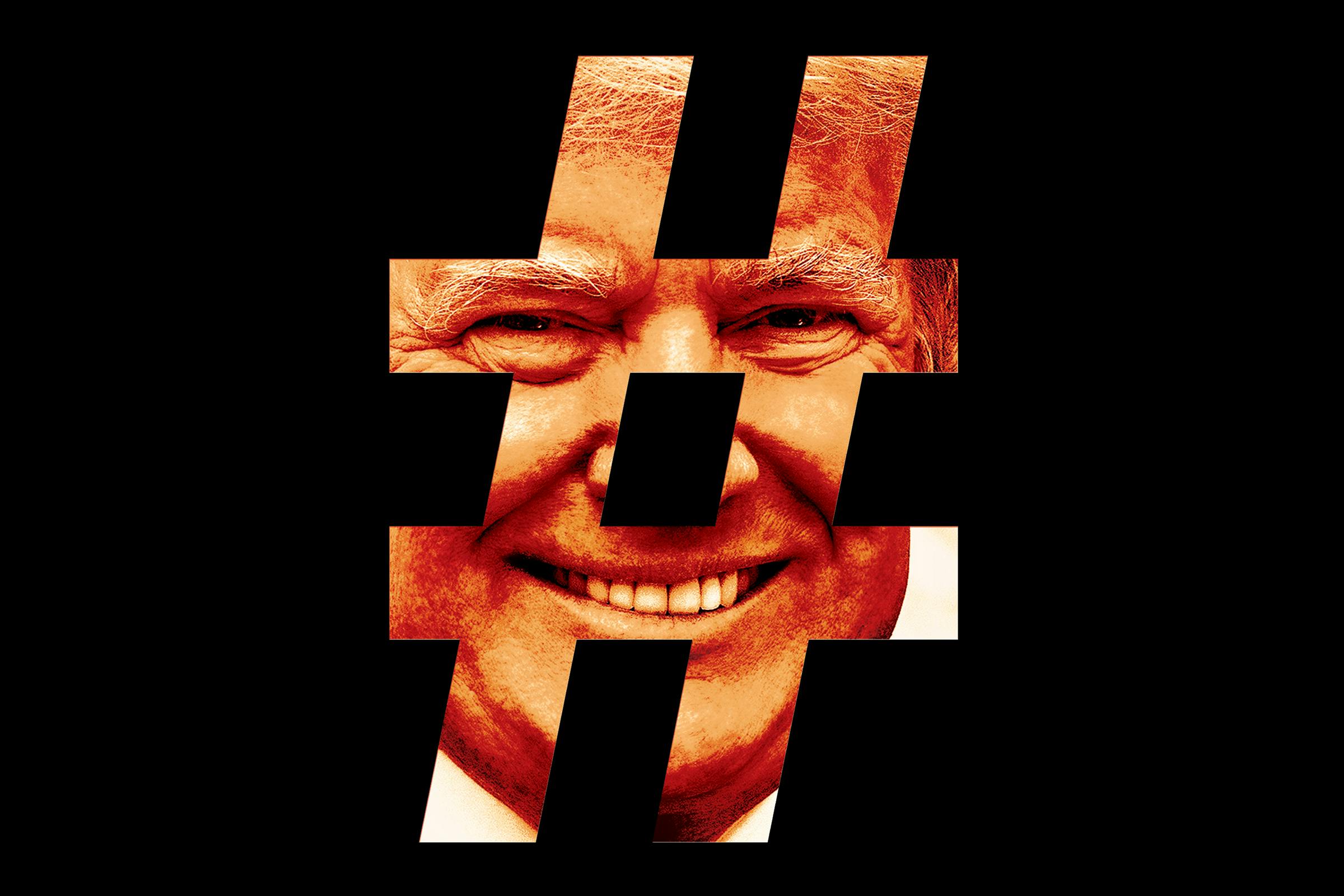

When does a movement become a Movement?

It is a vexing question. Invoking the term is meant to denote seriousness, to suggest that the activism you are engaged in will not disappear with the passing of the news cycle or be headed off by the most recent tidbit of celebrity gossip. A movement digs deep, plants roots, and grows until its objectives are achieved. There are today no agreed-upon benchmarks to be reached in order to call something a movement: No law must be passed, no number of people assembled in the public square. Anyone with a cause can claim the term in order to benefit from the gravity it connotes. With such a low barrier to entry, it becomes harder for even the most benevolent social critics to distinguish “thoughtful networks of dissent built over time,” as the historian Blair L.M. Kelley defines a movement, from those that are branded as such without any effort to be one.

The Resistance, the ubiquitous term for all manner of anti-Trump activity, emotion, and intention, came into being shortly after election night in 2016. This was a bitter moment for any American who until then had believed that the historical arc of the country bent toward progress. The presidential election presented a stark choice, between the first woman president and a “short-fingered vulgarian” with a long history of saying—and doing—openly racist and sexist things. Donald Trump was a symbol of an ugly past that had to be overcome, and embodied a rancorous desire to grasp those old “truths,” as was evident in his campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again.” In Hillary Clinton, Americans devoted to progress had placed their hope for the future, some begrudgingly, others enthusiastically. They were greatly disappointed.

Two years on, it remains self-evident that the Trump presidency poses a grave threat to democracy, nonwhite people, and even our ability as human beings to inhabit the planet. It remains equally apparent that there is a collective responsibility to resist—him, his supporters, what they mean, what they want—though what shape that resistance should take, and what demands it places on those who partake in it, are less apparent. The Resistance—capitalized into a movement—was supposed to answer that. It should be a source of power in contending with Trump’s destructive agenda. Instead it has been little more than a tool, a form of branding, for the most benign type of opposition, trading on the radical resonance of the word “resistance” in order to appear more powerful than it actually is. The Resistance is a movement in the sense that those who have taken up its banner call it a movement, but no more than that. It is a movement because it is rather than because it does.

Perhaps it’s unfair to ask the Resistance to be anything more than that. It may, charitably, be best understood as a social media campaign rather than a movement. If that is so, it may even have been effective. Movements require organizing on a grand scale—of people, money, and other resources—to wage effective legal challenges, coordinate direct action, politically educate newcomers, and build institutions. The Resistance has not produced any of those things. Or rather, it has not produced these movement hallmarks within the context of the Resistance as a movement unto itself. What it has done is given people a slogan under which they can rally. It has allowed them to find others who are frustrated, isolated, and afraid. It has raised awareness and kept people informed about some of the most pressing issues of this still young presidency. That’s worth something.

Joining the Resistance, as political historian Beverly Gage put it in The New York Times a year ago, does not “require adherence to any particular ideology or set of tactical preferences. It simply means, in the biggest of big-tent formulations, that you really don’t like Donald Trump, and you’re willing to do something about it.” A coalition that simple, formed around a shared dislike of a single person, has one upside: numbers. Donald Trump is a historically unpopular president who badly lost the popular vote. The tent is large.

The problem with a coalition of that sort is not everyone thinks they are in the same one. Trump has created enemies of all political stripes—anarchists, socialists, liberals, and a fair number of conservatives. The only groups he has not alienated are white evangelicals and alt-right neo-Nazis. In this way, he is a “uniter.” But unity is overvalued in movements, as it matters more what you are uniting around and whether you act in solidarity. With so many competing viewpoints, solidarity within the Resistance is essentially impossible to achieve, and really seems to be beside the point.

Still, the Resistance does have an apparently left-wing bent. People on the left were the ones most dismayed by Trump’s victory, and who initially claimed the mantle of Resistance. But the thirst for more resisters has meant welcoming anyone with even an incidentally critical thing to say about Trump. David Frum and Bill Kristol are friends of the Resistance. George W. Bush is in the Resistance. (He’s not.) Omarosa Manigault Newman, a former assistant to the president as well as former contestant on his reality game show, was greeted by the Resistance when she exited the White House. Fired FBI Director James Comey “joined” the Resistance because he took notes on conversations he had with Trump that could potentially be incriminating. It mattered little that Comey was at least in part responsible for Trump’s election, or that he was a longtime member of an institution responsible for violating the civil liberties of activists and marginalized people. It’s the type of thinking that led The New Yorker to declare John McCain’s funeral “the biggest resistance meeting yet.” The Resistance has embraced anyone with the temerity to speak against the president. That is all. But it is not enough.

This would seem to be by design. The objection to Trump is based less on his policy positions than on his personality. That is, while there has been opposition to the most odious parts of his political agenda, what has truly animated the Resistance is disdain for Trump’s character. He is a bully who insults and condescends to people with whom he disagrees, or who insufficiently praise him. He lies, blatantly and frequently, in a way that is either pathological or part of a convoluted strategy for manipulating the truth. He speaks in incoherent sentence fragments and never resists an opportunity to brag, even when his self-adulation is based on partial or complete falsehoods. Trump is, in short, not presidential.

He is so unpresidential that when he meets the minimum requirements of decency, he is praised as if he has done something consequential. When he addressed a joint session of Congress early in his presidency, he managed to read his prepared speech from a teleprompter without the bluster that characterized his campaign rallies or press conferences, and at one point honored the wife of a slain Navy seal. “He became president of the United States in that moment, period,” CNN’s Van Jones declared. No matter that the speech contained outright falsehoods about immigration, crime, welfare, the federal budget, and that it overstated the impact the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines would have on job creation (not to mention the disastrous environmental impact and displacement of indigenous people). What mattered was his presentation. Trump briefly sounded like a president. That should not have been enough. But for a moment it was.

#trump-hash { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; } [data-letter-sparkle] { white-space: pre; overflow: hidden; font-size: 10px; line-height: 100%; font-family: monospace; font-weight: 700; letter-spacing: 0px; background: #e15f2c; -webkit-transition: all 0.75s cubic-bezier(0.445, 0.050, 0.550, 0.950); -moz-transition: all 0.75s cubic-bezier(0.445, 0.050, 0.550, 0.950); -ms-transition: all 0.75s cubic-bezier(0.445, 0.050, 0.550, 0.950); -o-transition: all 0.75s cubic-bezier(0.445, 0.050, 0.550, 0.950); transition: all 0.75s cubic-bezier(0.445, 0.050, 0.550, 0.950); -webkit-touch-callout: none; -webkit-user-select: none; -moz-user-select: none; -ms-user-select: none; user-select: none; } [data-letter-sparkle]:hover { background: black; color: #e15f2c; }The Resistance is not about whether one agrees or disagrees with Trump on the issues, whatever those may be. It is not about policy. It is about the threat that Trump poses to the idea of progress, the comforting notion, entrenched by the election of Barack Obama, that things in this country could get better without anyone having to give anything up to make that so. When Trump refuses to denounce white supremacist groups that have endorsed him, the issue becomes less that his beliefs line up with theirs, and more that he has not rhetorically separated himself from avowed white supremacists. It becomes embarrassing to witness him on a global stage push past other world leaders so that he can be in front of a photo-op. His sophomoric speaking style is far below the level of what presidents are supposed to be able to employ. He watches television compulsively and live tweets his favorite Fox News shows. He refuses to release his tax returns to be reviewed by the American people. He is deeply incurious and proudly so, refusing to sit for traditional presidential briefs or to read anything that doesn’t mention him by name. During a ceremony to reintroduce the National Space Council, he responded to Buzz Aldrin’s sarcastic exclamation of “Infinity and beyond!” by saying, “It could be infinity. We don’t really don’t know. But it could be. It has to be something—but it could be infinity, right?”

It’s not good to have someone with so little interest in knowledge as president, someone who flaunts his ignorance as a badge of populist pride. And that is the dilemma the Resistance faces in exercising any meaningful political power. Trump has defied the norms and expectations of the presidency, and American politics more generally, and succeeded. The Resistance has made heroes of those who have pointed this out. But it has not questioned the basic nature of the presidency, or the country. It is dangerous to believe there is some victory in removing one person from an oppressive system while leaving the system intact. This is a dynamic the Resistance has shown no interest in addressing. Until it does, it can never be a movement.

There is a gross underestimation of how norms produced the Trump presidency. The Electoral College is an American norm. Placating racist voters is the norm, and cuts across both parties. Distrust and disdain for women in positions of power is the norm. Executive orders that overstep the constitutional powers granted to the presidency are now the norm. Some norms need to be challenged. America’s liberals have only been willing to challenge them to the extent that they do not uncomfortably burden its ruling classes with drastic calls for change. The Resistance has reflected that stance. It is the major impediment to consolidating this would-be movement around an agenda worth fighting for. Even if the principal objective is the removal of Trump from office, what drives that cannot be a desire for a return to what was once defined as normal. That would only set the stage for another Trump to rise. The goal has to be a complete reconsideration of the American system of governance.

Resistance is a reactive state of mind,” Michelle Alexander wrote in The New York Times. “While it can be necessary for survival and to prevent catastrophic harm, it can also tempt us to set our sights too low and to restrict our field of vision to the next election cycle, leading us to forget our ultimate purpose and place in history.” Viewed this way, the word resistance itself provides the wrong framework for understanding what must be done. James Baldwin refused to say the “Civil Rights Movement” because it was a term applied by white media onlookers. He instead referred to the period of heightened activism in the 1950s and ’60s as the “latest slave rebellion.” The contrast in meaning is stark. The enslaved possess no rights to be protected, only a system of dehumanization and exploitation to rebel against. Phrasing it this way captures a very different, very dire political terrain, one that requires a higher level of militancy to effectively counter.

The Resistance is something else entirely. Its active distancing from militancy reveals as much. On January 20, 2017, the day of Trump’s inauguration, thousands of protesters in Washington, D.C., took part in a different kind of demonstration than the one that would follow the next day during the Women’s March. Two hundred and thirty-four people would be arrested and face charges including felony inciting to riot, conspiracy to riot, rioting, and destruction of property. The J20 march, as it came to be known, was not just anti-Trump but anti-capitalist and anti-fascist. Its participants left a trail of thrown objects and smashed windows. Police teargassed and arrested them.

These protesters were roundly denounced by those who supported the next day’s events. Indeed, the virtual absence of arrests among the estimated 500,000 to one million people at the Women’s March in D.C. (or among demonstrators at any of the other sites across the country) the next day was heralded as a sign of its success. These were peaceful participants in democratic action, unlike the rabble-rousers of J20.

There is something immensely powerful about orchestrating the largest single-day march in the history of this country, as the Women’s March is believed to be. Many of its participants had previously never attended a march or thought of themselves as actively political. But there is also something shortsighted about not simultaneously embracing the J20 protesters. Those repelled by their tactics see only destruction and chaos, rather than the inevitable direct confrontation of state power—inevitable if there is a goal past the removal of Trump. The two years of his presidency have shown that he is a uniquely dangerous president, but his ascent was made possible by entrenched interests that predate him. He is only the latest representative.

Confrontational resistance is justified because conventional processes can only do so much to mitigate harm. Voting, in particular, is effective only to the point that it is understood that the citizenry will forcefully dissent from governance if its will is not honored. But it must also be understood that the problems Trump represents do not only exist at the state level. What is now called the “alt-right” has been organizing itself, in the shadows, for decades. Its adherents have developed alternative information channels, formed online communities, adopted a common language, and mobilized in ways that have found a home in the Republican Party.

Their agenda is best understood in the simplest terms: white supremacy. And yet they have been treated with an inordinate amount of benign curiosity, as if they present some fresh ideological viewpoint worthy of consideration in what is, in name, a multiracial democracy. Profiles of their supposedly dapper media leaders have portrayed them as fairly innocuous.

But as the killing of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville in August 2017 showed, the violence of white supremacy is both broader and deeper than the apparatus of the state under Trump. The young men photographed clad in polos and khakis, carrying torches and yelling “Jews will not replace us!” are not minor actors in a political game. They are a vicious threat.

The Resistance has not settled on an adequate response to this threat. Months before Heyer was killed, the alt-right provocateur Richard Spencer made headlines, not for his inflammatory rhetoric, but for being the subject of a viral video in which an antifa activist punched him in the face. The violence was decried, in some circles, as the wrong approach to his growing influence. It was also suggested by some liberal voices that other tactics, like protesting paid speaking engagements for the likes of Milo Yiannopoulos and Steve Bannon, were also outside the bounds of civility and proper discourse. Better to expose their ideas and debate them with a superior vision of an American future.

This misjudges the extent of their appeal, the composition of their threat, and naively places faith in the American populace that it will reject nativist, xenophobic, racist ideologies for their core maliciousness. There is less progress on that front than many would like to believe.

It also presumes that alt-right white supremacists can be somehow shamed into receding from public life or driven from it by force of argument. But no simple denunciation is capable of producing the level of shame needed to elicit the desired effect. Nor is the political terrain conducive to the task. Nonviolent protest, aside from its moral dimensions, has been successful as a tactic because the imagery of the violence it seeks to provoke has had the ability to shame those in power on a global scale. In the United States, however, that was most effective when there was a competing global superpower that could exploit discord within the country as propaganda in an anti-U.S. crusade. With America’s current hegemony, there is little that can be done to shame our leaders, and the grassroots of the alt-right are no different. When confronting people who gleefully rip children away from their families and place them in cages at the border, under the guise of criminality but actually in an effort to establish a white ethnonationalist state, shame, as strategy, fails.

The Resistance has had its greatest success in elections. There have been meaningful defeats of Republican candidates in key races. The first came against Roy Moore in the December 2017 special election in Alabama to fill then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s vacated Senate seat. Democratic nominee Doug Jones was able to beat the Trump-endorsed candidate, due in part to multiple allegations of sexual assault against Moore, including that he had improper relationships with minors. As narrow a victory as it was, it nonetheless counted and served as an important signal that Democrats could win contests outside their traditional strongholds.

But the party has had to contend with the split that showed itself during the 2016 presidential campaign. Senator Bernie Sanders mounted an impressive campaign that tapped into the concerns of many young people, and reflected a potentially far-reaching ideological shift. Yet the Democratic establishment, and cautious party members, nominated Hillary Clinton, who ultimately lost. Sanders’s success, and Clinton’s failure, were clear signs to those on the left that their time had come. The reluctance of party officials to concur has frustrated those who feel the Democratic Party, as currently constructed, cedes too much ground to Republicans and cannot serve as an effective opposition against Trump. When Maxine Waters, one of the president’s most boisterous critics, voiced her agreement with activists disrupting Trump officials’ everyday activities, such as eating dinner in a public restaurant, Senator Chuck Schumer denounced the idea from the floor of the Senate, saying, “I strongly disagree with those who advocate harassing folks if they don’t agree with you…. If you disagree with a politician, organize your fellow citizens to action and vote them out of office. But no one should call for the harassment of political opponents. That’s not right. That’s not American.”

Any real resistance would understand that the party ostensibly on its side has done little to advance its agenda, even within the narrow scope of defeating Trump. And yet, experienced, centrist Democrats are still viewed by many within the party as best equipped to lead, at least in the near term. They haven’t given anyone any reason to believe they are.

The surprise primary win in June of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over the incumbent Joe Crowley in New York’s 14th Congressional District was the first sign from within the party that big changes could be afoot. Ocasio-Cortez received little press attention before her win, and ran as a member of the newly reinvigorated Democratic Socialists of America.

Still, it would be easy to overreact to this single win. Ocasio-Cortez prevailed in a blue district and faced an opponent who did not take her seriously enough. She was shocked by her victory on election night. But the midterms in November delivered exactly what her win seemed to portend: a wave of Democratic victories that consisted of important demographic shifts toward electing women of color who situate themselves in the left flank of the party.

For all the celebration of this development, it is far from certain that the party establishment will adjust course. The drug of bipartisanship is difficult to kick. “Finding common ground” might have seemed reasonable before Trump, although the agenda of the Republican Party has been practically the same for the past 40 years. But now a new question must be raised: What about white nationalism do Democrats think is worth negotiating?

The Resistance, if it is a movement, cannot be too preoccupied with the Democratic Party as an arm of its organization. Institutions as old as the party are primarily concerned with survival. The extent to which the Democrats can be pushed in any given direction will be determined by whether or not they fear a mass exodus from their ranks. With no viable alternative party available to liberal and left-leaning voters, there is no reason to believe such an egress will happen.

The Resistance will have to ask something more of the people who have taken it up. There is a politics beyond that which created Trump. There are labor strikes, sit-ins, boycotts, and, yes, smashed windows and Nazi punching. But if it is to persuade a meaningful number of people to consent to such tactics, much less adopt them, the Resistance has to show itself as a true movement, one worthy of the name it carries and more meaningful to the people who are participating. It needs to find a definition and purpose beyond Trump.

And when those goals have been identified, the Resistance needs to settle in for the drudgery of movement work. It has to accept that this is a fight longer and more difficult than a presidential term, even two. The Resistance can be more than what it has shown thus far. It can be the very political movement that saves America from itself. If it wants to be.

No comments :

Post a Comment