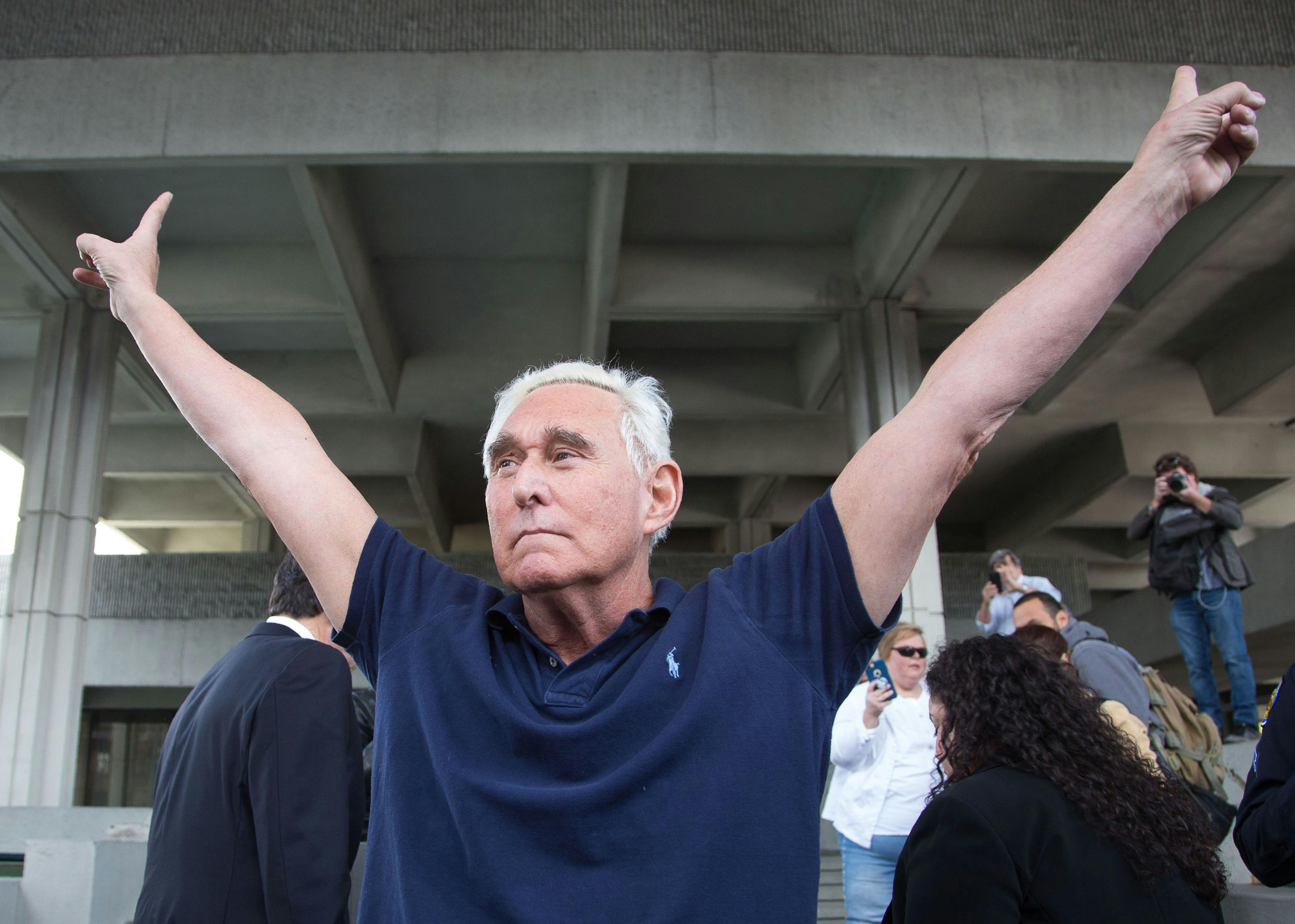

From the way some have spoken about Roger Stone’s arrest last week, a casual observer could be mistaken for thinking that the veteran GOP political operative and longtime Trump adviser was the victim of some monumental injustice. “If Roger Stone’s arrest is a sign of things to come, we’ve lost our country,” read the headline of a Sean Hannity op-ed on Fox News’ website. “Say goodbye.” His colleague Andrew Napolitano, a former state judge, called the arrest “the behavior of a police state where the laws are written to help the government achieve its ends.”

Stone’s treatment by federal agents who apprehended him is indeed scandalous—just not quite in the way that his defenders think.

Last Friday morning, special counsel Robert Mueller’s office unsealed an indictment against Stone that charged him with lying to Congress and witness tampering. At the same time, roughly a dozen FBI agents arrested him at his home in Fort Lauderdale. The agents, clad in body armor and helmets, knocked on Stone’s door shortly before dawn to rouse and apprehend him. Many Americans awoke that morning to footage by a CNN freelancer showing the arrest as it unfolded.

Stone, who is no stranger to hyperbole, played the victim immediately after his initial court appearance. He claimed that the FBI had treated him worse than drug lords or terrorist leaders. “To storm my house with greater force than was used to take down bin Laden or El Chapo or Pablo Escobar, to terrorize my wife and my dogs, is unconscionable,” Stone told reporters. It’s worth noting that U.S. soldiers shot bin Laden in the head during a 2011 raid in Pakistan and dumped his corpse off of an aircraft carrier at sea.

Other conservatives soon joined the chorus, however. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, who also chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a letter to FBI Director Chris Wray this week asking for more details about Stone’s arrest. “I am concerned about the manner in which the arrest was effectuated, especially the number of agents involved, the tactics employed, the timing of the arrest, and whether the FBI released details of the arrest and the indictment to the press prior to providing this information to Mr. Stone’s attorneys,” Graham wrote. Representative Doug Collins, the ranking Republican member of the House Judiciary Committee, sent a similar letter.

It’s true that Stone’s arrest was atypical—in that it ranked pretty low on the spectrum of police militarization. The Washington Post’s Radley Balko, who has more experience covering police use-of-force problems than just about anyone, had a more measured take on what Stone experienced. “A dozen agents w/ guns out seems excessive,” he wrote on Twitter. “But it didn’t look like SWAT team. Wasn’t a no-knock. No explosives. No dynamic entry. Maybe not ideal, but far better treatment than your average pot dealer.”

Other responses suggest that partisan concerns may be a greater factor here than genuine issues with law enforcement policy. Hannity, a fervent loyalist of President Trump, responded to the arrest with his usual partisan umbrage. Why, he asked, weren’t obvious crooks like Hillary Clinton, former CIA Director John Brennan, or former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper facing the same treatment? “We are a democratic republic,” he inveigled. “The Constitution that we cherish so much is the foundation of all law and order in this country. If you don’t apply the laws equally, only going after one group of people because of their political views, and you protect people with other political views, you’ve lost our Constitution. We’ve lost our country.”

Even typically cooler heads on the right spoke up in Stone’s defense. Napolitano, a Fox News legal analyst, is usually a voice of moderation in conservative circles when it comes to the Russia investigation. “No innocent American merits the governmental treatment Stone received,” he wrote in an op-ed on Thursday. “It was the behavior of a police state where the laws are written to help the government achieve its ends, not to guarantee the freedom of the people—and where police break the laws they are sworn to enforce. Regrettably, what happened to Roger Stone could happen to anyone.”

What happened to Roger Stone can indeed happen to anyone. It just rarely happens to people like Roger Stone. Police militarization is a widespread problem in American society. It erodes trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve, and may therefore have a counterproductive effect on crime rates and police violence. While it may have been overkill to send twelve armed and armored federal agents to arrest the 66-year-old Stone before dawn, it’s certainly not extraordinary under American standards. His experience just happens to be more commonly experienced by communities of color and Americans from disadvantaged backgrounds.

This is something of a theme for Trump-aligned conservatives in recent years: co-opting liberal and libertarian rhetoric about law-enforcement abuses to raise doubts about what appear to be legitimate steps in the Russia investigation. In the summer of 2017, for example, news outlets reported that federal agents carried out a no-knock search warrant during a predawn raid at the home of Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign chairman. Such warrants are typically used if investigators think the suspect may destroy evidence, and they’re hardly uncommon. John Dowd, one of Trump’s personal lawyers in the Russia investigation, nonetheless told a reporter that the raid amounted to a “gross abuse of the judicial process” and resembled tactics seen “in Russia not America.” (The FBI subsequently denied that a no-knock raid had taken place.)

After federal agents executed a lawful search warrant against former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen last May, conservatives once again saw the specter of tyranny. “We’re supposed to have the rule of law,” former House Speaker Newt Gingrich warned on Fox News. “It ain’t the rule of law when they kick in your door at 3:00 in the morning and you’re faced with armed men and you have had no reason to be told you’re going to have that kind of treatment. That’s Stalin. That’s the Gestapo in Germany. That shouldn’t be the American FBI.” The Anti-Defamation League condemned his comparison to the Nazi regime.

Perhaps the longest-running line of criticism focused on the Justice Department’s use of a FISA warrant against Carter Page, a former Trump campaign foreign policy aide with multiple ties to Russian figures, during the 2016 campaign. House Republicans and conservative media outlets spent months focusing on purported surveillance abuses, casting Page’s treatment as part of a wider “deep state” plot to undermine Trump’s campaign and presidency. The grievance campaign became a victim of its own success when House Republicans released a partially redacted memo on the warrant that undercut Trump’s own claims about his campaign and Russia.

The goal here ultimately is to discredit the Russia investigation, to cast it as thuggish, partisan, and illegitimate. Drawing upon good-faith concerns about surveillance abuses, prosecutorial overreach, and law enforcement militarization is a clever way to go about this. But it also speaks volumes about those who invoke it. The question isn’t really why they’re concerned about such heavy-handed tactics against one of Trump’s ex-confidantes. It’s why they aren’t expressing similar concerns when it happens to anyone else.

Last month, with the inauguration of a newly elected Democratic governor fast approaching, Michigan’s Republican legislators made a last-minute attempt to ram through a bill to dramatically weaken public-sector unions. The bill would have required those unions to hold a recertification vote every other year, subjecting them to possible dissolution on a regular basis and forcing them to spend scarce resources on elections rather than on organizing. It was the first time the bill had made its way onto the floor, but its contents were familiar: Much of the legislation’s language was copy-pasted from a “model bill” introduced by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) at the group’s annual meeting just a few months earlier.

It was one of hundreds of model bills similarly designed by the corporations, trade associations, and legislators that make up ALEC, a “private-public” organization with shadowy financing that has long been an influential resource for Republican lawmakers across the country. A flurry of state laws in the past ten years weakening labor unions, restricting voting, allowing environmental degradation, and bolstering gun rights have their roots in legislation drafted by ALEC, which has acted as a kind of government in waiting, helping Republicans move with all speed once they take over a given statehouse. But ALEC’s recent appearance in the Michigan lame-duck session revealed that the group has plans for when Republicans are out of power as well—which could affect legislation in states where Democrats are inching closer to winning back control as we head into the 2020 election cycle.

To the relief of the hundreds of protesters who showed up at Michigan’s capitol in Lansing to protest the deluge of Republican bills, the union recertification proposal didn’t get enough votes to pass. But many others did, including bills to minimize the impact of a minimum wage increase, limit paid sick leave, restrict ballot initiatives, and curb the power of the incoming governor. During Wisconsin’s lame duck session, Republican lawmakers pulled a similar stunt, passing a number of bills transparently designed to rein in the authority of the incoming Democratic governor just weeks before he took office. While the union recertification was by far the most direct ALEC copy-cat, there were several others introduced in the Great Lakes states that, according to Brad Bauman of the Stand Up to ALEC coalition, “have ALEC DNA all over them.”

In Wisconsin, lawmakers passed new restrictions on early voting remarkably similar to legislation struck down by a federal judge in 2016—a pet project of ALEC legislators at the time. Another ALEC favorite to pass during the state’s lame duck limits the governor’s power by preventing him from changing administrative rules. ALEC adopted its own Administrative Procedures Act model legislation in September, designed to “reduce the regulatory burden on private enterprise and rebuff the administrative state’s encroachment on individual liberties.” In Michigan, the legislature passed into law a bill that bans state and local agencies from requiring public disclosure by nonprofits, much like ALEC’s model policy on “donor privacy,” which anti-ALEC groups refer to as a “dark money” policy that allows right-wing groups to extend their influence.

Democrats won back seven governorships, six state legislative chambers, and more than 300 state legislative seats in November. A number of other states, like Florida and Georgia, came close to breaking up the Republican stranglehold on their respective governments. Democrats are hoping that opposition to Donald Trump, combined with a new awareness about the importance of rolling back Republican dominance at the state level, will help tilt the field in their favor in the next couple years. But as the party focuses on building power in the states, these lame-duck power grabs sent a stark message that Republican state power is not built on seats alone, but on a power structure that can’t simply be voted out of office. ALEC’s role, increasingly, is to solidify that structure in the face of a blue wave.

ALEC rose to national prominence following the 2010 midterms, when Republicans gained a devastating 721 seats, bringing a total of 25 state legislatures under total GOP control. And in many of those states, change came swiftly. “It took a long time for them to get the omnipotent power that they did in 2010,” said State Representative Chris Taylor of Wisconsin. “But once they did, they knew what they wanted to do, and they did not waste any time.” (Democrats have been known to sponsor ALEC bills, too, on issues like education and health care, but Republicans are far more likely to do so. In 2011, Democrats sponsored nearly 10 percent of the total ALEC model bills introduced, while Republicans sponsored more than 90 percent, according to Brookings.)

In Taylor’s state of Wisconsin, then-Governor Scott Walker, backed by a strong Republican majority in the state legislature, immediately passed legislation to strip public workers of their collective bargaining rights and signed a budget cutting public school funding by more than $1 billion. In the 2011-2012 session, Walker signed into law 19 bills or budget provisions at least partially based on ALEC model bills, according to the watchdog group Center for Media and Democracy (CMD). In 2015, Walker’s “right to work” bill was a near verbatim copy of ALEC’s right to work bill.

“I was gobsmacked—fascinated but so horrified over the power and very functional infrastructure they’ve built over the last 45 years on the right,” Taylor said. She realized that the same was true, to varying degrees, in conservative legislatures across the country, from Michigan to North Carolina to Kansas. ALEC’s efforts have been bolstered by the State Policy Network, an umbrella organization for conservative think tanks; Americans for Prosperity, a Koch-funded libertarian advocacy group; and local conservative hubs like the Bradley Foundation in Wisconsin and the Mackinac Center in Michigan.

The election of Democratic Governor Tony Evers—which was seen as a referendum on corporate power in Wisconsin, thanks in part to Walker’s unpopular decision to offer an unprecedented $3 billion subsidy to a new Foxconn plant—gives Taylor hope that ALEC’s influence in Wisconsin is waning. ALEC’s power base has been weakened at the corporate level, too: Over 100 corporate members and funders have cut ties to the group over the past several years, as criticism of the “bill mill” has spread. Some of these companies, such as Verizon and AT&T, quit after ALEC selected anti-Muslim activist David Horowitz, named by Southern Poverty Law Center as “one of America’s most dangerous hatemongers,” to headline its 2018 summit. “There are visible cracks in ALEC world,” Taylor wrote in an article exposing details of Horowitz’s speech.

But ALEC remains a powerful force. Yes, some companies have left, but the majority of its members are still there, including many trade associations of which the defecting companies are a part—and some anti-ALEC advocates warn that the diminished influence of more moderate companies has allowed ALEC to shift ever more to the right. Yes, Democrats have taken back power in key ALEC strongholds, but Republicans still hold total control in 22 states. And because of power-grab bills in states that did buck unified Republican control in 2018, it’s clear that incoming Democratic governors won’t have as much power as ALEC-backed governors did in the same seats.

Precedent suggests that these laws will be successful. When Democratic Governor Roy Cooper’s election in 2016 ended three years of Republican control in North Carolina, legislators enacted several bills diminishing his power. In the two years that Cooper has been in office, the Republican-dominated legislature has overridden 29 of the governor’s vetoes. Last year, when a reporter asked state Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger about any further plans to strip the governor’s power, he replied, laughing, “Does he still have any?” According to CMD, 28 of North Carolina’s legislators have ties to ALEC.

“ALEC teaches state lawmakers to think about policy not as a way of solving problems but as a way of building political power,” explained Alex Hertel-Fernandez, who recently published State Capture, a book about ALEC and other conservative policy groups. According to Hertel-Fernandez, the difficulty of undoing ALEC’s handiwork through elections is not a side effect of the group’s policy strategy, but an essential aim. The broad reach of ALEC, along with the State Policy Network and Americans for Prosperity, has made this anti-democratic approach to policymaking a crucial part, he argues, of what it “mean[s] to be a conservative, pro-business state legislator.”

By focusing on policy areas that target the very landscape of who gets to have power, these groups have essentially guaranteed that the tide, if it turns against them, will do so slowly and painstakingly. Thanks to ALEC-backed gerrymandering legislation in Michigan, Wisconsin, and North Carolina, for example, Republicans retained state legislative control in November, despite the fact that Democrats received the majority of votes. Research shows that right-to-work laws—which destroy unions’ ability to donate and organize for pro-labor candidates—cost Democratic candidates between two and five percent of the vote in an average election and lowers voter turnout by approximately two percent.

“For Democrats to take advantage of their gains, they need to have that organizational landscape to buttress their lawmakers,” said Hertel-Fernandez. Winning seats isn’t enough, he argues, if Democrats can’t institute policies that grow Democratic legislative power in the long term. “I don’t see that being built in a significant way,” he added.

Absent strong public-sector unions, or sufficient long-term investment in state or local power-building from progressive funders, some left-leaning organizations have emerged to offer necessary coordination between state lawmakers, advocates, and researchers. The State Priorities Partnership (SPP) and the Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN) both operate as state-level networks of center-left think-tanks producing research on issues like welfare reform and the minimum wage and helping coordinate between legislators in various states. The State Innovation Exchange (SiX) helps draft progressive legislation that lawmakers adapt to their local context, offering a type of support similar to what ALEC has long provided to conservatives.

November heralded a hopeful opening to repeal harmful ALEC-backed legislation and advance a progressive local agenda. In Kansas, where Democrat Laura Kelly replaced incumbent Governor Kris Kobach (who once bragged about trying to persuade ALEC to expand its anti-voting rights campaigns), progressive legislators are working to expand education funding and Medicaid. In Colorado, where Democrats gained both the governor’s mansion and the state legislature in November, the focus is on expanding local control over minimum wage laws and access to paid family leave. Such “quality of life” legislation is seen as essential to undoing some of the damage ALEC-backed legislation has done not just to people’s lives, but to democracy as a whole. “One of the things that’s been so destructive about ALEC over the years is the way they’ve been able to completely undermine people’s faith in government,” said Naomi Walker, director of EARN. “If progressives would focus more on passing local and state policy that could really make a difference in people’s lives it would help reverse some of the undoing of our social fabric that ALEC has been able to achieve.”

Through knocking down the pillars of ALEC’s anti-democratic agenda, advocates like Walker hope to reclaim states from conservative monopoly. Progressive policy groups are counseling legislators on how to make the redistricting process in their states more transparent ahead of 2020. Voting rights has become a rallying point for progressive groups across the country. And campaign finance reform, which would hamper ALEC’s cash-flow, is gaining traction, too.

But balancing such aspirations with beating back the constant barrage of anti-democratic legislation from the right poses a challenge. In Florida, as progressive challenger Andrew Gillum threatened to overtake Governor Rick Scott in the polls, Republicans pushed for a constitutional amendment to limit property tax increases, which was approved. Voters approved a similar amendment in North Carolina, where Democrats broke the Republican supermajority on November 6. “The strategy has to be to stay a step ahead of it and spot these trends,” said Nick Johnson, who directs SPP. “We’ve been working to try to put a spotlight on that stuff early enough so we can block it before it takes effect.”

In Virginia, where Democrats are close to flipping the state legislature next year, the power grab is already quietly underway. After a federal panel of judges last week approved new district lines in the state that strengthen potential Democrat-leaning districts, Delegate Mark Cole, a former ALEC Education Task Force member, introduced a constitutional amendment to require equal partisan representation in the state’s independent redistricting commission, regardless of districts’ shifting party preferences. As democratic contests across the country begin to tilt against the right wing, there seems to be no limit to its assault on the rules.

To be a parent in the 1950s was to know that your child would at some point contract measles, a highly contagious virus characterized by fever and rash. When it happened, most parents needed only to plan for a few days of care. But about 500 every year planned funerals.

The first measles vaccine in the U.S. was introduced in 1963, and the disease was officially eliminated in 2000. Since 2008, however, it has been creeping back. Nearly 350 measles cases were diagnosed in the country last year, the second-highest number since its eradication. Just one month into 2019, it seems certain that this year will be even worse.

At least 35 people, mostly children, have been diagnosed with measles in Washington state since January 1, prompting the state’s governor, Jay Inslee, to declare a state of emergency. Around 40 more have been diagnosed in New York this month, part of an outbreak there that’s seen at least 186 cases since October. Public health officials expect the outbreaks to spread further, and attribute both of them to the same problem: An increasing number of parents are refusing vaccinations for their kids.

Across the United States, children are required to be immunized from life-threatening diseases before they’re allowed to enter school or daycare. This not only protects the child from disease, but ensures that schools are safe places for immune-compromised kids and adults, as well as kids and adults who are medically unable to get vaccines. Vulnerable groups such as these rely on herd immunity, which is achieved when around 90 to 95 percent of the population is vaccinated.

The majority of parents who reject these requirements today, however, aren’t from vulnerable groups. They’re opting out for their own religious or personal beliefs. Parents aren’t legally allowed to do that in every state, but can in the two states experiencing major measles outbreaks. Religious exemptions are permitted in New York, where the outbreak is primarily affecting the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community. Both personal and religious exemptions are allowed in Washington, which according to one infectious disease researcher has become “a major anti-vaccine hot spot due to non-medical vaccine exemptions that have nothing to do with religion.”

Routine childhood vaccination programs have been shown to prevent approximately 42,000 early deaths and 20 million cases of disease per year, saving $13.5 billion in direct costs. That’s why non-medical exemption laws are opposed by the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Infectious Diseases Society of America—basically every reputable medical organization out there. But nearly every state has them in some form. There is also “tremendous variability in the rigor with which such beliefs must be proved or documented,” according to the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS). In some states, “parents simply need to state that ‘their religion’ is against vaccination to be granted an exemption, even though no major religions specifically discourage vaccination.”

These problems are being compounded by the growth of the anti-vaccine movement, which argues that vaccines are more dangerous than the government and medical community claim, and thus no vaccines should be mandatory. Neither their facts nor their logic holds up. “Parents cannot be exempted from placing infants in car seats simply because they do not ‘believe’ in them,” argues PIDS. States also don’t allow belief exemptions for laws intended to protect other people, like driving a car without a license. “Whether or not children should be vaccinated before childcare or school entry ought not be a matter of ‘belief,’” the group argues. “Rather, it should be a matter of public policy based on the best available scientific evidence, and in this case the science is definitive: vaccines are safe and they save lives.”

So why doesn’t Congress just pass a vaccination law outlawing non-medical exemptions? “We would love it if they could do something at the federal level,” said Rich Greenaway, the director of operations for the advocacy group Vaccinate Your Family. “We’d be 100 percent behind it.” But it’s not clear that Congress has that legal authority. According to the Congressional Research Service, “the preservation of the public health has been the primary responsibility of state and local governments, and the authority to enact laws relevant to the protection of the public health derives from the state’s general police powers.” Creating a federal vaccination law would turn that historical precedent on its head.

A federal vaccination law would also set the stage for a fierce legal battle with vaccine opponents that would almost certainly make its way to the Supreme Court. The risk of losing that battle, while providing a major platform for anti-vaxxers, might not be worth it. Besides, the state’s authority to set vaccination requirements was already confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court over 100 years ago, and federal lawmakers also don’t have much interest in taking that authority away, Greenaway said. “The legislators at the federal level, they kind of know that their states want to handle this and they step back from it.”

But there are other ways the federal government can influence vaccination policy. The feds provide most of the funding for state public health agencies, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides states with nearly all their funding to buy vaccines for children whose parents don’t have medical insurance to cover the costs. They could put restrictions on the money—say that they won’t provide funding to states if their vaccine programs allow personal belief exemptions—but that’s a risky approach. What if states accuse of the government of overreach and reject funding instead of comply? Would they then have no vaccine program at all?

The best approach, Greenaway says, is to provide states with bigger rewards for success in preventing the spread of diseases. “In a perfect world, we’d love to see more incentives, where a state might get a higher percentage of federal funding when they do well so they can continue to work toward getting the numbers even higher,” he said. The CDC could also offer grants to private health insurance companies or doctors who demonstrate that they’ve kept a high percentage of their patients up to date on vaccinations. The Department of Education could offer financial incentives to schools that consistently demonstrate a highly vaccinated population.

But for the most part, Greenaway thinks vaccination is an area where the federal government is doing nearly everything it can. “The CDC works really hard on this,” he said. “They’re constantly coming up with public information campaigns, and trying to put in money into research to see whether or not certain things work.”

It will be up to individual states, then, to do more to prevent outbreaks—and perhaps the surest way of accomplishing that is by tightening exemptions. The California legislature eliminated personal belief exemptions in 2015 after an outbreak that originated at Disneyland infected at least 111 people, nearly half of whom were unvaccinated. Since then, vaccination rates among kindergartners increased by nearly 5 percent—though so have medical exemptions.

Paul Harris, a state representative in Washington, is hoping for the same outcome in his state. This week, he introduced a bill that would eliminate the personal exemption. It won’t be an easy sell, even though it preserves the religious exemption and comes amid a measles outbreak. A similar bill in 2015, prompted by the Disneyland outbreak and supported by Inslee, failed in the state House. Less than four months later, Washington was home to the first measles death in America in a dozen years.

For most of the nation’s history, the most common way to read court filings was to travel to the courthouse itself, pull up a desk in the clerk’s office, and leaf through them by hand. This was hardly a convenient system, especially if you lived in a far-flung rural area or lacked the resources to travel to a nearby courthouse for the task. But it was still an impressive one. Public access was a core principle of the American federal judiciary, which absorbed both the Founders’ disdain for secretive British courts and their belief in the democratic virtue of open legal proceedings.

Then came the Public Access to Court Electronic Records system in the 1990s. In theory, the federal courts’ electronic docket system—known universally as PACER—allows anyone with an internet connection to call up the motions, briefs, orders, and appendices for virtually any federal court case. The interface has not evolved with the times. In an age of sleek, minimalist web design, PACER is a clunky and nonintuitive portal into the courts’ inner workings. What’s more, it’s overcharging its users.

Now a medley of legal advocacy groups, media outlets, and former politicians and judges are asking the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals to rein in excessive PACER fees. Some of the organizations argue that the current payment structure violates federal e-government laws that prohibit unnecessary fees. Others see the fees as a threat to judicial transparency and openness. What’s ultimately at stake is the ability for Americans—including journalists and defendants—to fully participate in the nation’s legal system.

Three legal nonprofit groups—the National Veterans Legal Services Program, the National Consumer Law Center, and Alliance for Justice—filed a class action lawsuit against the federal government in 2016 to challenge PACER’s fee structure. They argued that by charging more than the marginal costs to keep the system functional, the judiciary had run afoul of a federal law dedicating PACER’s fees solely to that purpose. “Instead of complying with the law, the [federal judiciary] has used excess PACER fees to cover the costs of unrelated projects—ranging from audio systems to flat screens for jurors—at the expense of public access,” they told the district court in 2016.

The case hinges on a single phrase in the E-Government Act of 2002. The statute authorizes the judiciary to levy fees “only to the extent necessary” to provide “access to information available through automatic data processing equipment.” Though data storage costs have plummeted over the past two decades, PACER’s fees rose from seven cents a page at its establishment to ten cents a page by 2011, which remains the cost today. That may not sound like much, but it adds up fast. The PACER system itself brought in more than $146 million in fees during the 2016 fiscal year, even though it cost just over $3 million to operate.

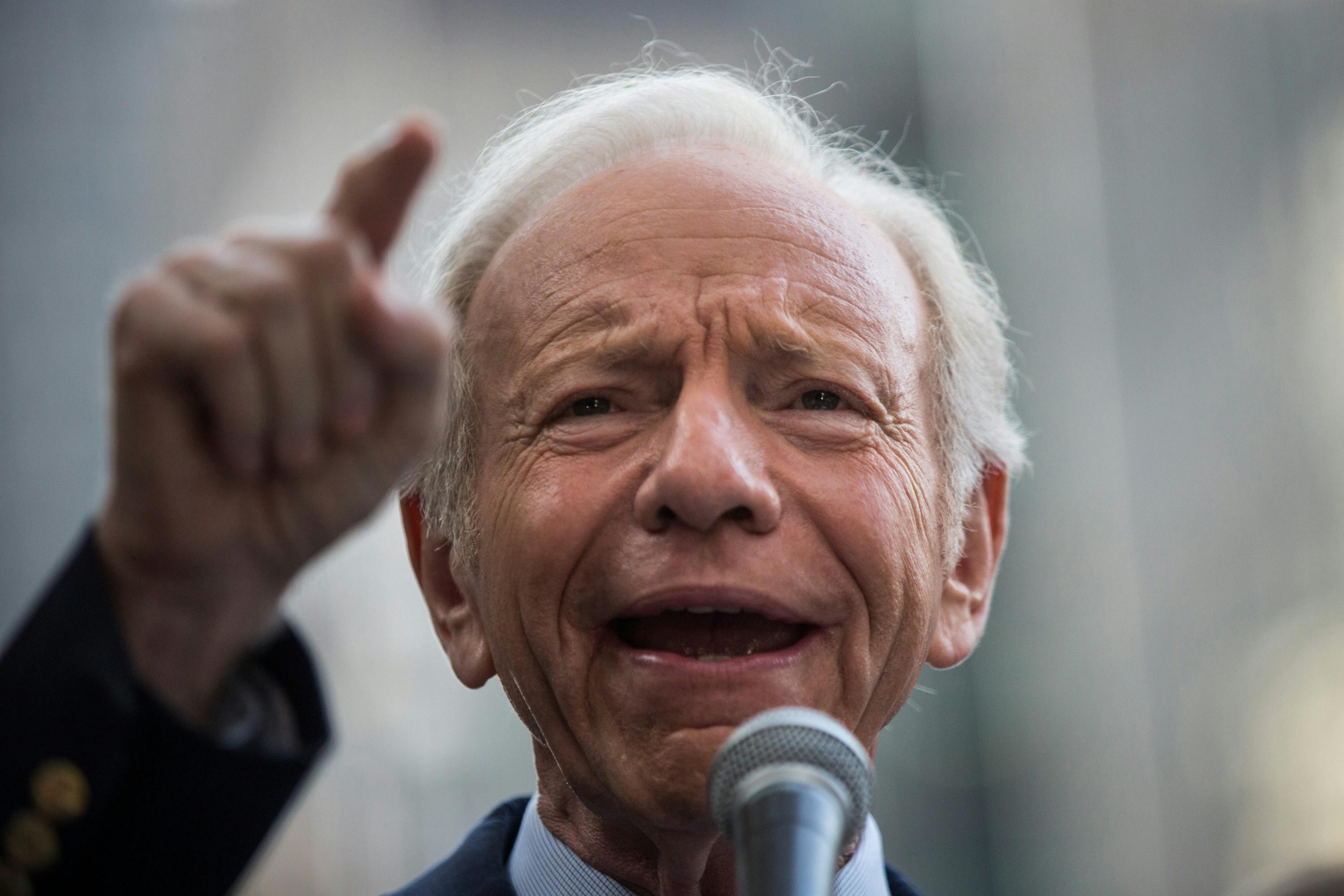

“Anyone who wants to be able to access the documents that are essential to understanding the way our court system works has to pay these fees,” Brianne Gorod, the chief counsel at the Constitutional Accountability Center, told me. The organization filed a friend-of-the-court brief on behalf of former Senator Joe Lieberman, the 2002 law’s original sponsor. “What that means is that one’s ability to access these documents—to read the briefs that the courts use when making decisions, to understand why courts are doing what they do—is going to turn on one’s financial situation.”

The government countered that Congress gave the courts broad discretion to levy fees that would fund the judiciary’s entire slate of public access services. “Notably, this authorization makes no mention of PACER,” Justice Department lawyers told the district court. What did those funds go toward? Between 2010 and 2016, the judiciary spent $185 million in PACER fees to fund a variety of improvements to courtroom technology; $75 million went toward automated notices for creditors in bankruptcy cases during that same time period; and another $3.5 million funded Violent Crime Control Act notifications to local law enforcement agencies.

Last March, federal judge Ellen Segal Huvelle took a Solomonic approach. She refused to endorse the government’s sweeping interpretation of the E-Government Act or the plaintiffs’ narrow version. Nonetheless, she ruled that some of the judiciary’s expenditures went beyond what Congress had authorized. Using PACER fees to fund electronic filing access for lawyers and send out automated bankruptcy notices survived scrutiny; expenditures like a web portal for prospective jurors and a study on electronic filings in Mississippi state courts did not. The plaintiffs and the government both asked the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals to review the decision.

In his friend-of-the-court brief, Lieberman argued that the lower court had misinterpreted the law and its intent. He speaks with some authority on the matter, having introduced the Senate’s version of the E-Government Act and overseen its passage as a committee chairman. In his filing, Lieberman warned that excessive PACER fees would “impose a serious financial barrier to members of the public who wish to access court records, and these fees thereby create a system in which rich and poor do not have equal access to important government documents.”

Media organizations also warned that PACER’s fee structure undermined journalists’ ability to report on legal affairs. The groups, which included news outlets like The New York Times, Politico, and BuzzFeed, raised First Amendment concerns about the system’s effect on public access to the courts. Digital journalism’s dire financial straits—another troubling sign for American democracy—made the situation even more acute. “In this environment, many news outlets simply cannot afford large fees for court records,” the groups told the court in their brief last week.

A group of former federal judges, including prominent jurists like Richard Posner and Shira Scheindlin, went even further. In a friend-of-the-court brief filed earlier this month, they argued that PACER should charge no fees at all, citing the need for judicial transparency and the benefits for researchers, journalists, and prisoners who represent themselves in court. “Given the public’s strong interest in accessing court records, the judiciary should bear the cost of PACER’s operations,” the brief said. “This is consistent with the courts’ longstanding tradition of providing free access for all who come into the courtroom.”

The Federal Circuit has yet to schedule a date for oral arguments in the case, and a final ruling may not come until next year. If the plaintiffs prevail, PACER users who accessed the system between 2010 and 2016 may see some of their expenses refunded by the federal government. Until then, PACER will keep building a wall between Americans and the public records that they have a right to access, nickel by nickel and dime by dime.

The discussion around criminal justice reform these days usually centers around the same four or five themes. We need to change sentencing laws and guidelines so people aren’t thrown into prison for unreasonable terms. We need to fix policing to better hold accountable those officers who discriminate or use excessive force. Our prosecutors must begin to take a fairer view of what crimes should be aggressively prosecuted, even if it means fewer indictments. And when we do jail people for crimes, we must give most of them a meaningful opportunity to be released from pretrial detention. There is broad, bipartisan support for most of this.

What we almost never talk about when we talk about the need to fix our justice systems is the labyrinth of procedural hurdles established by legislators and judges to thwart the ability of the wrongfully convicted to get relief. We focus on figuring out how not to put innocent people in prison, which is great, but we don’t focus enough on figuring out how to get them out of prison after they’ve been convicted. The prime example of this, of course, is the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, the Clinton-era federal law that vitiated habeas corpus review and made it measurably harder for justice to come to criminal defendants who deserve it.

But it’s at the state level where these procedural hurdles are most pernicious. Take, for example, the case of Johnny Lee Gates. Earlier this month, a trial judge in Columbus, Georgia, ordered a new trial for Gates decades after he sought one. That’s the good news. If ever a defendant deserved a new trial, it’s Gates. From the start, his case was marked by a level of official misconduct I’ve rarely seen in nearly a quarter-century covering criminal justice. Police never even arrested another man who confessed to the murder for which Gates was subsequently charged.

The bad news is that the judge cited a series of arcane state appellate rules to avoid basing his ruling on the most egregious component of Gates’s conviction: the fact that prosecutors systematically excluded black citizens from his jury pool. In a three-day period in 1977, Gates, an intellectually disabled black man, was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for murdering a white woman. An all-white jury heard the case and that’s because prosecutors had put a “W” next to the list of white prospective jurors and an “N” next to the list of black prospective jurors before moving to strike from the case all of the black candidates.

“The evidence of systematic race discrimination during jury selection in this case is undeniable,” wrote Judge John Allen. And not just undeniable, in Judge Allen’s view, but patently intentional. He devoted nearly 10 pages of his 27-page ruling chronicling how prosecutors purposely violated Gates’s constitutional rights by deploying one racist tactic after another. And then, after all that, the judge declared that he could not grant Gates a new trial based on this discrimination because of a six-part procedural standard Georgia courts apply in requests to overturn old convictions.

Every state has built into its criminal justice system rules designed to bring a measure of certainty and finality to old convictions. It makes sense. We all can agree that defendants cannot forever be entitled to raise new claims. But in Georgia, and in other states, the barriers to new evidence are way too high. For example, Gates had to prove that he didn’t know about the jury discrimination when it occurred at trial, that it wasn’t his fault that he didn’t learn of it until decades later, and that the discovery of the prosecutorial misconduct “probably” would have changed the outcome of his trial.

The judge didn’t explain why the proof of intentional racial discrimination wasn’t enough to grant Gates a new trial. It can’t be because Gates’s lawyers were diligent in seeking to raise the issue. The judge inexplicably didn’t mention in his motion how hard Georgia officials fought to keep secret those old notes from Gates, the ones that proved the racism at the heart of the 1977 trial. Instead, Judge Allen ultimately found that Gates deserved a second chance because newly discovered DNA evidence demonstrated “that he is excluded as the contributor to the DNA of two key items of physical evidence” in the case.

Gates is lucky in a sense. The case against him was so weak, and the evidence of official misconduct so pervasive, that his lawyers were able to surmount the procedural obstacles put into place by Georgia judges and legislators. But many other defendants in Georgia and beyond continue to serve wrongful convictions. The problem is acute, especially, when convicted defendants try to establish that their lawyers provided them with ineffective assistance of counsel. The problem has been eased in the past decade or so, on the other hand, when it comes to post-conviction DNA testing, thanks in large part to the Innocence Project.

At the heart of the matter is the role of reviewing courts. We all are taught in high school about how the system of appellate review in this country is supposed to weed out mistakes at trial. But over time, the system has devolved to the point where it tolerates, even encourages, unjust results. With one piece of legislation, Georgia could make it easier for defendants like Gates to establish their right to a new trial. Eliminate the need for a defendant to prove the new evidence “probably” would have generated a different result. Redefine what “due diligence” means where, as in Gates’s case, prosecutors or police are hiding evidence.

Likewise, with one single state supreme court ruling, Georgia’s judiciary could do the same. That six-part test the trial judge applied in Gates’s case? It could be refined. Today, a defendant like Gates must meet each of the six prongs of the test. How about a new standard that allows judges instead to balance out those factors? If a defendant proves, for example, that the new evidence is particularly material, he doesn’t necessarily also have to prove that he could not have discovered it five years earlier.

Why these reforms haven’t happened isn’t hard to figure out: There is no powerful political or legal constituency fighting on behalf of the unjustly convicted.

It comes down to competing values. Georgia lawmakers have placed a higher value on the certainty and finality of old convictions than it has on the accuracy and reliability of those convictions. That six-part test Gates struggled with is designed more to discourage dubious post-conviction motions than it is to encourage legitimate ones. And we never will know the true cost of that balancing because we will never know how many wrongful convictions in Georgia have gone unidentified because innocent defendants failed to meet the onerous procedural burdens erected against them.

Gates may soon go free if prosecutors choose not to retry him. So why am I complaining? Isn’t this a story that proves the system, in the end, does work? Yes and no. It worked for Gates. But the next wrongfully convicted defendant who raises these claims will also run into those procedural hurdles and likely won’t have DNA evidence to spare him. And you can bet in that, in cases to come, state lawyers will cite the Gates opinion to argue that even blatant racism by prosecutors doesn’t, on its own, justify a new trial. I don’t think you can call that progress. I think you call that a particularly despicable form of resistance to justice.

No comments :

Post a Comment