Progressives have been practically leaping for joy since 28-year-old self-described democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won her primary election for Congress last week, an outcome that CNN called “the most shocking upset of a rollicking political season.” But perhaps no group has been more excited than environmentalists. In a political environment where even her fellow Democrats often stay vague on climate change, Ocasio-Cortez has been specific and blunt in talking about the global warming crisis. She also has a plan to fight that crisis—one to transition the United States to a 100-percent renewable energy system by 2035.

To achieve this ambitious goal, she has proposed implementing what she calls a “Green New Deal,” a Franklin Delano Roosevelt–like plan to spur “the investment of trillions of dollars and the creation of millions of high-wage jobs,” according to her official website. “The Green New Deal we are proposing will be similar in scale to the mobilization efforts seen in World War II or the Marshall Plan,” she told HuffPost last week. “We must again invest in the development, manufacturing, deployment, and distribution of energy, but this time green energy.”

These positions have earned Ocasio-Cortez significant positive press. HuffPost called her “The Leading Democrat On Climate Change;” Vice called her “the Climate Change Hardliner the Planet Needs.” But those stories also note the political obstacles in Ocasio-Cortez’s way. There’s the climate-denying Republican Party, of course, but there are also Democrats, who have largely ignored climate change this election season and lack an organized plan to tackle it. How can a plan like Ocasio-Cortez’s see the light of day when her own party seems likely to bury it?

If @Ocasio2018 wins, it'll be a historic victory for the climate movement.

Her proposal -- outlined here in an email to me -- to deal with global warming is among the only equitable and scientifically realistic policies put forward by any Democrat running this year. pic.twitter.com/UDJKBNcifZ

But an equally important question is whether such a plan would, from the scientific perspective, work. Very few plans politicians have floated recently have even come close to the level of drastic change researchers say the world would need in order to halt global warming before it reaches dangerous levels. How does this one stack up?

If and when Democrats do decide to mobilize on global warming, climate scientists tell me their plan should look at least something like Ocasio-Cortez’s. “A plan of the magnitude and pace proposed by Ms. Ocasio-Cortez would be a critically important step in the right direction, albeit long overdue,” said Jennifer Francis, a research professor at Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences. Michael Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State, agreed. “This is just the sort of audacious and bold thinking we will need if we are going to avert a climate crisis,” he said.

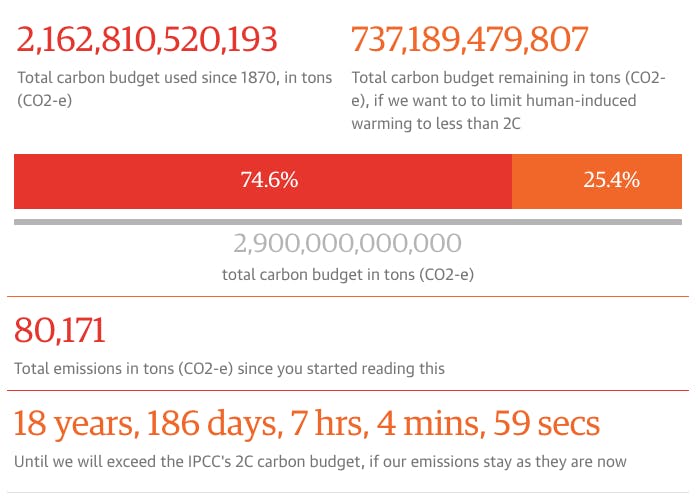

Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that aggressive action is needed to stave off the violent storms, rising seas, and debilitating droughts projected to worsen as the climate warms. Avoiding that means the earth’s average temperature can’t rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above where it was in the year 1880. Unfortunately, we’re already nearly there; as The Guardian’s Carbon Countdown Clock shows, humans can only emit greenhouse gases at our current rate for another 18 years before we reach the 2-degree mark. We can buy more time, however, if we stop emitting so much greenhouse gas. “The science is pretty clear—we want to reduce emissions, to near zero, as fast as possible, if we want to minimize climate change,” Texas A&M University climate scientist Andrew Dessler told me. That means rapidly decarbonizing the U.S. economy—much like Ocasio-Cortez has proposed.

A snapshot of The Guardian’s “carbon countdown clock” from 6 p.m. EST on July 1, 2018.theguardian.com

A snapshot of The Guardian’s “carbon countdown clock” from 6 p.m. EST on July 1, 2018.theguardian.comBut for most of the the climate scientists I spoke to, their alignment with Ocasio-Cortez’s plan stops there. That’s not because they don’t want a 100-percent renewable energy system by 2035, but because the Green New Deal lacks some important details. “How will energy be stored as an economical cost if only using wind and solar? What is the role for nuclear power in such a plan? Who will fund this transition?” said Penn State climate scientist David Titley, also the former chief operating officer of NOAA. “I’m very skeptical such a transition can be done in a period less than 20 years from what is basically a standing start.”

How the Green New Deal would be paid for was a common point of contention—after all, Roosevelt’s New Deal was paid for by massive cuts in government spending, tax hikes, and decreased pay for government workers. “This would, I think, not be something that Republicans would support,” Dessler said, stating the obvious. Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said he believed a gradually implemented carbon tax would be the only way to garner support for the plan. “This provides all kinds of incentives, gets the private sector engaged, and implements it in a way that is not a shock to the system but which allows good planning to occur,” he said.

The climate scientists I spoke to also noted that quickly transitioning to renewable energy wouldn’t be enough to completely solve the climate crisis, because we’ve already emitted so much carbon dioxide and will continue to inevitably for at least two decades. (You can’t take all the cars off the road at once.) “The heat-trapping greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere will remain there for at least a century and cause additional impacts,” Francis said. “For this reason, the plan to convert to renewable energy sources must be accompanied by efforts and resources to develop technology that can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, along with a carbon fee to discourage further extraction and burning of fossil fuels.” A comprehensive climate change plan must also account for adaptation to those inevitable impacts. After all, “Climate change is already with us and costing billions per year,” Trenberth noted.

Ocasio-Cortez’s plan to fight climate change may raise important and difficult questions, but they’re questions that establishment Democratic Party leaders should have answered long ago—not just for the planet’s sake, but for the sake of the party’s political future. In the wake of devastating hurricane and wildfire seasons fueled by global warming, Democratic voters are more motivated by climate change than ever before. Ocasio-Cortez was perhaps more keenly aware of that than others: Her mostly-Latino constituency is more worried about climate change than other demographic groups, and her own grandfather died in Hurricane Maria. But if the party is still searching for lessons from her shocking win, she’s made one pretty clear: an aggressive, full thought-out, party-wide climate plan is long overdue.

Every now and then, The Washington Post publishes something that provokes uniquely murderous rage from readers across the political spectrum. On May 24, that something was a recipe. For hot dogs. Made of carrots.

“If you show up to my cookout with carrot dogs I’m setting you on fire,” NFL blogger Lindsey OK tweeted, one of many threats of bodily harm made in response to Joe Yonan’s recipe for charred and steamed carrots, adapted from the Chubby Vegetarian cookbook. Golf Digest deemed the recipe a “despicable” and “horrid” idea that would “possibly ruin” Memorial Day Weekend. The conservative news show Fox and Friends aired a two-minute segment poking fun at the carrot dog, too, which featured host Pete Hegseth eating a raw carrot shoved between two buns. Ashley Nicole Black, who writes for the liberal comedy show Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, also got in on the fun. “If you put a carrot inside a hot dog bun and call it a vegan hot dog, I will cut you,” she tweeted.

Yonan’s recipe clearly hit a nerve. “I was very surprised by the vehemence of the anger,” he told me, comparing the reaction to the infamous New York Times recipe for pea guacamole. “People felt personally assaulted by these carrot dogs, as if I was throwing them out of a cannon.” Criticisms were made not just of Yonan’s recipe but of Yonan himself for making it. “The lamestream media really does want America to hate them,” libertarian scholar Aaron Ross Powell wrote.

If eating “real” hot dogs makes you as angry and violent and inhospitable as some of the folks responding to @washingtonpost about the stellar @chubbyveg Carrot Dogs I made, I will count that as another reason I’m happy to be #vegetarian . @WaPoFood

— Joe Yonan (@JoeYonan) May 25, 2018On the one hand, America really loves hot dogs. The National Hot Dog and Sausage Council says Americans consume around 20 billion hot dogs per year—about 7 billion from Memorial Day to Labor Day—and that sales remain steady due to the growing popularity of high-protein diets. “Experts believe sales of the entire refrigerated processed meat category will continue to grow in the future,” the Hot Dog Council claims, despite the rise of millennials concerned about the environmental impacts of factory farming and the health impacts of processed foods.

But liking the taste of processed meat doesn’t explain why people get so mad at suggested alternatives. That may have more to do with the hot dog’s longstanding place in American culture. “This is a food specifically geared to American patriotism,” says culinary historian Bruce Kraig, who has written two books about hot dog culture around the world. America’s hot dog patriotism did not occur by accident, he says, but by design: starting with an early national desire to distinguish America as a meat-eating (and therefore prosperous) country. It then spread like wildfire due to savvy advertisers who sought to capitalize on that desire.

“Underlying the defense of hot dogs is the idea of American values,” Kraig said. “In this case, those values are xenophobia and American exceptionalism.” If those values were powerful enough to help secure the presidency for Donald Trump, it’s no wonder they helped secure the hot dog’s place in Americans’ hearts.

The hot dog’s origin story is murky, but a few things are concrete. It’s a sausage made mostly of beef or pork. The original recipe came from Germany. It started proliferating in the U.S. in the late 19th century. “A hot dog was the first way to get cheap meat on the go,” Kraig said. “Even before hamburgers.”

Cheapness and portability were the keys to the early hot dog’s success. As American farmers began raising vast quantities of livestock, meats became cheaper and accessible beyond rich households. The cheapest meats were sausages made of less savory parts of the animal, and thus those were the products shoved into buns and sold by vendors at fairs, baseball games, boardwalks—anywhere on the street, really. (Nathan’s Famous, for example, started as a 5-cent hot dog stand opened by Polish immigrants on Coney Island in 1916).

The public squares where hot dogs were sold—baseball games especially—were melting pots for all different ethnicities and incomes. And everyone ate hot dogs. “They quickly became a democratic food,” Kraig said. “People start to have this feeling that they’re all Chicago White Sox fans—they forget their ethnic differences. Hot dogs are there for part of it.”

That feeling of togetherness, and therefore patriotism, was badly needed in post-Civil War America. But the rise of cheap meats—fueled by hot dogs but also salisbury steaks—fed into more nationalist sentiments, too. Americans began to feel as though they were better than Europeans, who didn’t have enough land for grazing to make meat cheap enough for the masses. “If you’re a working-class factory worker in Liverpool, you’re not going to eat as much meat,” Kraig said. “But working-class Americans could get it, and they knew that,” feeding a patriotic sense of superiority that played into late-nineteenth century American xenophobia, as well. In turn, “Most Europeans were absolutely appalled” by the level of meat-eating in early America, Kraig said. Hot dogs brought Americans together while setting them apart from the rest of the world.

A 1943 ad for Skinless Weiners from the Visking Corporation.Paul Malon/Flickr

A 1943 ad for Skinless Weiners from the Visking Corporation.Paul Malon/FlickrBut it was twentieth-century advertisers who turned hot dogs into a nation-wide, values-linked symbol of American identity. In the 1930s and 40s, The Visking Corporation—which sold “Skinless”-brand wieners—advertised them as a July 4 food; a food for fighting soldiers; a food that was good for rationing (since there was “no peeling or waste”; and a food that was good for kids.

Children became a particularly important selling point for hot dogs in the 1950s and 60s, as the end of World War II saw explosions in marriage and birth rates. In 1963, Oscar Mayer released its iconic jingle, “I’d love to be an Oscar Meyer Weiner.” Four years later, Armour Hot Dogs’ came out with the lesser-known “The Dog Kids Love to Bite.” That strategy of marketing to children, Kraig said, put a 20th-century spin on hot dog nationalism: “Children were part of our American values.” And advertisers, whose job it is to “see what’s going on and use it for commercial purposes,” noticed.

In the middle of the century, patriotism, nationalism, xenophobia, and an emphasis on traditional family structures proliferated regardless of party identity. The values that fueled hot dog patriotism, however, are held most strongly today within the Republican Party, which perhaps explains the political leanings of the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council. The group—which promotes July as National Hot Dog Month, July 18 as National Hot Dog Day, and holds an annual hot dog lunch for Congress—was founded by the North American Meat Institute (NAMI), which sends 81 percent of its political donations to Republicans. For years, groups like NAMI have lobbied against federal nutritional guidelines recommending eating less meat. Once, NAMI called a criticism of the meat industry an attack on the “American way of life.”

But meat-eating is becoming less of a way of life for many Americans, which is exactly why Yonan wrote his carrot dog recipe in the first place. “It was merely an option for vegetarians who don’t want to eat a hot dog,” he said. “No one’s trying to take your hot dog out of your hands at your cookout.”

For what it’s worth, America’s premiere hot dog historian applauds the effort. He’s just not sure it’ll catch on. “Things are changing rapidly in America when it comes to food,” Kraig said. “But very few Americans are going to grill a carrot.”

This article has been corrected to reflect that National Hot Dog Day is July 18, not July 19.

It is rare to see a work of art met with a rapturous reception. Sure, there are always fans, but I’m talking about fanatics. I’m talking about work that makes instant evangelists of those who behold it, that has people rushing to their social channels to urge strangers to watch this now, it changed my life and it will change yours too. When it happens, that kind of swooning tends to pass into legend; we roll our eyes when we hear about people passing out in front of Impressionist nudes at Parisian salons as if they’d never seen cellulite before. But every now and then, a work by a new voice breaks through, and sharing it with others becomes a compulsion, even a kind of moral duty. This is what has happened in recent weeks with Hannah Gadsby’s revelatory hour-long comedy special Nanette, which started airing on Netflix in late June.

Gadsby is a queer woman from Tasmania; she spent her whole life living slightly adjacent to the mainstream, but never quite veering into it. With Nanette, that is all changing. “I’ve been a professional comic for 30 years,” the comedian Kathy Griffin wrote, “I thought I had seen everything...until I watched Nanette.” Monica Lewinsky called it “one of the most profound + thought provoking experiences of my life.” Television producer Gloria Calderon Kellet said it “is one of the most beautiful & tragic reflections of our world.” The Bob’s Burgers writer Wendy Molyneux wrote “I don’t want to tell you how to live but i gently forcefully suggest you watch the @Hannahgadsby special “Nanette” on @netflix.” The set was supposed to be Gadsby’s comedy swan song—she announces halfway through that she is quitting comedy—but its popularity may be a a sign that the industry is changing, or at least that it is in desperate need of change.

Above all else, Nanette is an interrogation of comedy as an art form, a bracing inquiry into the ways that comedians use the medium to mask personal truths. Early on, Gasby admits that, as a gay woman in comedy, who wears dapper tuxedo jackets and sports a short swoop of brown hair, she spent the first decade of her career making self-deprecating jokes. She cheekily calls this her “lesbian content,” which she says she no longer feels comfortable including in her sets. “I don’t want to do that anymore,” she says, about 17 minutes into rapid-fire punchlines, her tone turning suddenly somber. “Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it comes from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility. It’s humiliation. I put myself down in order to speak, in order to seek permission to speak. And I simply will not do this anymore.”

Gadsby opens the show by dismissing its title. “The reason my show is called Nanette is because I named it before I wrote it,” Gadsby says, in her gravelly Tasmanian accent. Gadsby’s delivery, throughout the Netflix special, is both whimsical and droll. She has a habit of delivering her punchlines almost under her breath, with an impish grin. “I named it around the time I’d met a woman named Nanette who I thought was very interesting,” she continues. “So interesting, that I reckon I can squeeze a good hour of laughs out of you, Nanette. But, it turns out...nah.”

There is a palpable absurdity to this admission, a nonsensical detail plopped into the first 20 seconds of the set, designed to steer the audience off course. She is providing a subtle blueprint for the swerves her set will take moving forward: All of this is my invention, and this may not go where you expect. A good comedian, Gadsby later explains to the crowd, is really a virtuoso of control—they are constantly modulating the tension in a room, calibrating ways to release it in the collective catharsis of a laugh. Comedians are emotional con artists, Gadsby suggests, whispering into the microphone as if bringing the audience into a conspiracy. They are masters of misdirection, usually diverting the attention away from their own vulnerability. Comedy can be a mask and a shield, a hard mollusk shell that hides and protects the comic’s soft center. “A joke is simply two things, a set up and a punchline,” Gadsby explains:

It is essentially a question with a surprise answer. In this context, what a joke is, is a question that I have artificially inseminated with tension. I know that, that’s my job. I make you all feel tense, and I make you laugh, and you are like, thanks for that, I was feeling a bit tense. I made you tense! This is an abusive relationship.

This is the heart of it. Nanette is a show about abuse—about how comedians abuse audiences, how men abuse women, how society abuses the vulnerable people living on its margins. Gadsby says that in becoming a comic, she has been complicit in her own abuse and that of people like her, because she is covering up her stories of trauma with laughs, rather than digging deep into the marrow. “I need to tell my story properly,” she pleads halfway through the set, standing in a solo spotlight. “You learn from the part of the story you focus on.” What makes Nanette so remarkable is that Gadsby never stops being funny, but she starts being brutally honest, and she calls forth a wealth of historical knowledge to support her assertion that the world is set up to protect the cruel. What ensues is less a traditional comedy hour than, as the writer Natalie Walker observed, a “coup de théatre,” which is part art history lecture, part memoir, and part battlecry.

What makes Nanette so remarkable is that Gadsby never stops being funny, but she starts being brutally honest.“I don’t like Picasso, I fucking hate him,” says Gadsby, who holds a degree in Art History and mentions this fact several times as both a joke and a resumé item. “He’s rotten in the face cavity...I hate him and you can’t make me like him.” She is talking about a real-life abusive relationship, one in which a 45-year-old married man started sleeping with a 17 year old girl. In fact, as Gadsby tells us, Picasso’s affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter has become just another part of his oversized mythology as a tortured, insatiable artist. He once said that he wanted to burn all women when he was done with them, destroying them so that he no longer had ties to the past. Gadsby points out the inherent violence in this idea. “Picasso is sold to us as this passionate, virile, tormented genius man ballsack, right?” she says, rattling her fist, “But he did suffer a mental illness….the mental illness of misogyny.”

She contrasts Picasso’s macho image against that of Van Gogh, whom, she says, we idolize for making beautiful work despite his mental torment, when really he was living in hell and couldn’t sell paintings because he couldn’t network. “This whole idea, this romanticizing of mental illness is ridiculous,” she says. “It is not a ticket to genius. It is a ticket to fucking nowhere.”

The reason Gadsby brings up these looming artistic figures is not because she wants to take easy swipes at the dead. She does it because, as a woman who is very much alive and trying to make art, she says she grew up learning that these men (along with Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Roman Polanski) were the geniuses against whom she should measure herself, and in doing so found almost no room for her own voice. The only way she could be heard was to become the punchline, to hurt herself in public until others listened. In Nanette, she chooses to revise her methodology. No more hiding behind false tension.

Early on, she tells one story of a man who, mistaking her for a “bloke” who was “cracking onto his girlfriend,” threatened to beat her up in the street. The first time Gadsby tells this anecdote, the man recognizes his mistake and slinks away, humiliated by his ignorance. Later on, however, after Gadsby announces her need to tell the true story, her voice goes hushed. She leans into the microphone, her eyes watery. The man did not slouch away from the scene, she says. Instead, he returned, and he beat Gadsby so brutally that she should have gone to the hospital. The only reason she did not, she says, her voice cracking, is “because I thought that was all I was worth. And that is what happens when you soak one child in shame and give another permission to hate.”

“This tension is yours,” she tells the audience. She no longer wants to provide soothing relief.She lets the silence hang heavy in the room. “This tension is yours,” she tells the audience. She no longer wants to provide soothing relief. Gadsby says that she was molested and raped, because she is “gender not-normal,” and the least she can do is hold space for her own pain without cutting the moment, without covering it up with a one-liner bandaid. She needs her story to be heard, but more importantly to be felt.

At the end of her set, Gadsby returns to Picasso. She says he got away with his affair with Marie-Therese because he claimed that the girl was in her prime. Gadsby’s eyes squint with rage. “A 17 year old girl is just never ever in her prime. Ever. I am in my prime. Would you test your strength out on me?”

Gadsby is right. She is in her prime. In Nanette we witness the shock of the new, a voice that dares to speak to this frustrating and often hideous cultural moment, a comedian willing to drop the act. I would call Gadsby a genius, but she would likely push back against that term. The idea of genius gets us into trouble, she warns; it allows certain people to gain power and wield it over others. Gadsby, I think, would rather just be known as a human, full-hearted and flawed, full of bravery and grace.

No comments :

Post a Comment