At the Gamelab conference, Sony Interactive Entertainment America CEO Shawn Layden said the company is "confident" it will be able to allow cross-play.

At the Gamelab conference, Sony Interactive Entertainment America CEO Shawn Layden said the company is "confident" it will be able to allow cross-play.

Book publishing has reached a point of what could be called stable insecurity. The steep fluctuations of the post-Kindle years, in which rapid e-book growth seemed poised to upend the industry, have settled—for traditional publishers, at least, e-book sales have sharply declined over the past few years. Print books, thanks in part to pricing strategies that disincentivize e-book purchasing, have inched upward. Though hobbled, the industry’s most important retailer, Barnes & Noble, is still standing, while a rise in the number of indie bookstores has provided an important feel-good-story. Literary fiction is in crisis—sales are down 25 percent since 2012—and the bestseller list is dominated by books with “Trump” and/or “Russia” in their titles, but as a whole the industry has escaped what used to be a constant sense of crisis.

And if the overall picture is “meh,” there are some bright spots. The brightest might be the audiobook boom that’s taken place over the last few years. Earlier this month the Association of American Publishers reported that net audiobook revenue surged 29.5 percent in 2017, compared to the previous year. For some writers, audiobook sales are outpacing other formats. As reported by The New York Times in June, John Scalzi’s 2014 novel Lock In sold 22,500 hardcovers, 24,000 e-books, and 41,000 audiobooks. The print book’s unquestioned supremacy ended a decade ago; now we’re in an environment in which print books, ebooks, and audiobooks are of equal importance for many authors and publishers.

From a revenue standpoint, this is very good news for publishers. But it’s complicated. Audiobooks are dominated by Audible, which is owned by Amazon. Amazon effectively has the market for both e-books and audiobooks cornered. And Audible is working hard not just to maintain its market share but to grow it, expanding its production of original work and signing big name authors like Michael Lewis to exclusive contracts. When considered against the backdrop of Amazon’s ambitions to become an entertainment powerhouse, there are reasons for publishers to go back to being nervous.

Technological change is at the heart of the audiobook craze. Once unwieldy—the audiobook for George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones consists of 28 CDs—the smartphone made even the longest, heaviest book portable. The larger demand for audio storytelling (Audible also produces podcasts) has also played a role. But Audible’s particular success is largely tied to Amazon’s market dominance. Amazon owns electronic bookselling in general, so it’s no surprise that it would own electronic audio-bookselling as well. (It is also helped by its subscription service, which at $14.99/month essentially amounts to an audiobook at half price.)

The signing of Lewis last month tells us a lot about how far Audible has come, and how far it still has to go. Lewis is a nonfiction superstar, whose books, like Moneyball and Liar’s Poker, reliably sell hundreds of thousands of copies. Amazon has been publishing original fiction and nonfiction for years, but it has struggled to compete with traditional publishing houses when it comes to big names. Instead, Amazon’s print divisions have largely exploited inefficiencies, publishing books (like works in translation) that are neglected by the large New York publishing houses.

Audible’s success has begun to open that up. Lewis’s deal will encompass four Audible Original stories, the kind of longform magazine work he traditionally has produced for places like Vanity Fair. Lewis joins Tom Rachman (whose short story collection Basket of Deplorables was written for Audible before being published in print last summer), Robert Caro (whose bite-sized On Power was produced by Audible last year), Margaret Atwood (who created a special edition of A Handmaid’s Tale exclusively for the company), David Spade (whose forthcoming memoir will be released as an Audible Original next month), and Scalzi. Audible also crowed earlier this year about acquiring the rights to snowboarder Shaun White’s memoir, which it will release as an enhanced audiobook before Houghton Mifflin Harcourt publishes a print edition.

Audible isn’t exactly a giant-killer yet, but it is putting out an intriguing mix of content, one that—if you squint a bit—resembles the work being done by the publishing houses Audible simultaneously is partnering with and competing against. Audible is emphasizing its strengths while essentially taking what it can get from big-name authors—it’s a smart, patient strategy that is yielding results. We’re still a long way off from an author of Lewis’s caliber signing an Audible exclusive contract for an actual book, but that seems plausible for the first time. Earlier this year, The Wall Street Journal reported that Audible was pursuing deals where it would acquire audio, print, and electronic rights.

Print publishers have responded by spending more on audiobook production. Last year, Penguin Random House’s audiobook of George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo featured a cast of 166, including Ben Stiller, Lena Dunham, Julianne Moore, and Don Cheadle. Competition between Audible and publishers has been a rare boon for authors, with audio advances on the rise. But publishers have good reason to be concerned about Audible’s expansion, and its growing ability to attract top-shelf talent.

As Alexandra Alter noted in The New York Times last month, Lewis’s deal suggests that Audible is looking for ways to push publishers out of the audio realm, in order to grow its own profit margins (which take a hit, thanks to its bargain-priced subscription service). For publishers, audiobooks are important subsidiary rights that can be sold to help recoup the risk that they take on when they sign an author; given the high margins that they command, they are also increasingly important to publishers’ bottom lines, which are, as always, tenuous.

But it also points to Amazon’s larger goals. The company is embracing content creation at every level to woo subscribers, from its reported $1 billion Lord of the Rings TV show to its increased spending on original audio content. Years ago, when Amazon started publishing books, there was a worry that the company would undermine the publishing industry at every level—from book production to sales. That day never came. But now, with the rise of Audible, Amazon finally has a content production arm that can rival the large New York publishing houses.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misidentified the sales of John Scalzi’s Lock In as the sales of the author’s later novel, The Dispatcher.

On Sunday, an unconventional candidate prevailed in Mexico’s presidential election, preaching forgiveness, instead of punishment, for Mexico’s drug war criminals.

In debates and campaign ads, left-populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s opponents attacked his security proposals, including his call to offer amnesty for certain drug war crimes. While many details of the president-elect’s proposals have not been defined, what’s clear is that López Obrador, who won in a landslide, is poised to make a drastic departure from 12 years of heavy-handed policies against the drug trade.

“Amnesty turned into a symbol [during the campaign] around which diverse political figures positioned themselves,” says Froylan Enciso, a researcher and professor in the Drug Policy department of the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE) in Mexico City. “Those who believe we need to continue with the current security strategy, and those who want to change it.”

In a country devastated by over a decade of relentless violence, that change is a long time coming. The question now is whether López Obrador’s plan for reconciliation and amnesty can work.

Mexico’s strategy to stop narco-trafficking has stagnated. Since president Felipe Calderon began the war on drug-trafficking in 2006, rates of murder, kidnapping, and forced disappearance have increased around the country. Today, Mexico is one of the most violent countries in the world outside of active war zones. 2017 was the deadliest year since the start of the Drug War, with more than 29,000 murders.

Calderon deployed the army to patrol the streets, and since then the military has been involved in an ever-growing litany of human rights violations: extrajudicial killings, torture, rape. Last December, the Internal Security Law granted the military the right to carry out civil policing duties indefinitely.

“We have an unconventional armed conflict in Mexico,” said Enciso. “The war on drugs isn’t really a war against drugs, it’s a war against people, and communities.”

One study from the Mexican Senate, using data from 2012, found that among federal prisoners for drug crimes, eight in ten had not completed high school.That’s an increasingly widespread sentiment in a country where an astonishing 95 percent of murders go unsolved, even as the number of Mexicans detained for federal drug charges has risen. López Obrador’s proposals address an uncomfortable reality: the masterminds of the violence between competing cartels often go unpunished, while prosecution often targets the most vulnerable.

One study from the Mexican Senate, using data from 2012, found that eight in ten federal prisoners for drug crimes had not completed high school. Mexican NGO Equis reports that from 2015 to 2017, the number of women being prosecuted for drug-trafficking crimes doubled, most for minor offenses.

Christian de Vos, an advocacy officer at the Open Society Justice Initiative who researches Mexico, says that during outgoing president Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, instead of re-evaluating the strategy, “The strange phenomenon is that the Mexican government doubled down on these policies.”

López Obrador, by contrast, says that the root cause of Mexico’s violence is the lack of educational and work opportunities for young people. He has proposed scholarships for young people to learn a trade or go to university, and thereby rob organized crime of its labor pool.

Amnesty,

which may seem radical, is a proposal to match the extremity of the situation. “Mexico

is not in a normal situation,”says Loretta Ortíz Ahlf, a human rights lawyer

and member of López Obrador’s security advisory council, pointing to rampant

torture and forced disappearances. “We have to create the framework for a

transition to peace.”

The key, López-Obrador’s team believes, will be to pair amnesty with an intensified quest to solve some of the most disturbing unsolved cases of violence and human rights violations, holding the more powerful players responsible instead of the vulnerable pawns. Ortíz Ahlf says the plan is for the transition team to hold consultations around the country to develop a security proposal by the time they enter office in December. In his victory speech Sunday night, López Obrador referred to it as a “Peace and Reconciliation Plan for Mexico.” And they will propose a new office: the Sub-Secretary of Transitional Justice, Human Rights and Attention to Victims. One of the division’s first tasks will be to create Truth Commissions to investigate emblematic cases like the disappearance of 43 students at the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in 2014, as well as extrajudicial killings in places like Tlatlaya.

Information from these commissions will be passed on to the state and federal prosecutors’ offices for thorough, independent investigation. The Federal Attorney General (PGR for its Spanish initials) is closely linked to the executive branch, and investigations into human rights abuses like Ayotzinapa are often stymied for lack of political will. López Obrador has called for an independent federal prosecutor, who would not be beholden to political interests.

While those investigations go forward, Ortíz Ahlf says amnesty will be considered for vulnerable social groups, who were “co-opted” by organized crime. These social groups include young people, subsistence farmers, and indigenous people: rural farmers, for example, who decided to grow marijuana when other crops failed, or teenage boys paid to be look-outs for organized crime in poor neighborhoods.

The amnesty would exclude violent criminals such as murderers and torturers. Ortíz Ahlf says that only those committing to rehabilitation and to actively participating in the reconciliation process—for example attending mediation sessions with victims—would be able to enter the amnesty program.

While these plans may seem idealistic, they’re based on the principles of transitional justice, a set of legal mechanisms for countries where violence and human rights violations go beyond the legal system’s capacity to resolve them.

Transitional justice has been used in countries like Colombia or Guatemala while emerging from prolonged political conflicts. In Colombia, de-mobilized FARC members have access to re-integration programs, much like the educational and work opportunities for young Mexicans López Obrador proposed. Colombia’s Peace Accords took years to negotiate and had to be amended after voters opposed to the deal won with a narrow margin in an October 2016 plebiscite. Nonetheless, the historic process has allowed FARC militants to re-enter civilian life; the guerrilla organization, too, has transitioned into a political party.

While a right-wing politician, Iván Duque, won Colombia’s recent presidential election, the fact that a former leftist militant with the M-19 guerrilla organization, Gustavo Petro, came in second running with the Progressive Movement party shows that voters are willing to support former insurgents who integrate into electoral politics.

Fernando Travesí, Executive Director of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), says that many of the same principles can be applied in countries like Mexico, where irregular conflict surpasses the state’s capacity to prosecute crimes within its existing framework: the key is to make it a participative process that involves all sectors of society. “Dialog allows for people to express themselves and participate, so that later they have a feeling of ownership over the outcome,” he says.

While there is a basis in international law for amnesty, Travesí warns it must be legislated very carefully within the legal code of each country and painstakingly paired with programs to prevent recidivism. Mexico’s case is not the same as Colombia’s or other Latin American countries’, and Travesí emphasizes that there is no one-size-fits-all model for reconciliation.

Enciso, too, emphasizes the importance of embedding amnesty in a broader policy plan: “This needs to be paired with development programs, and opportunities for people who were caught up in illegal activities.”

And the thorough prosecution of those giving orders in the Drug War is a part of that. “In Mexico there is a need for accountability, and a need for reconciliation,” says de Vos. “Any discussion of amnesty must also be linked to seeking the truth.” He references the model of South Africa, where amnesty for apartheid-era violations was offered to some perpetrators who agreed to give full confessions.

The specter of U.S.–Mexico relations hangs over López Obrador’s election. His security platform is just one of many policy shifts that could disrupt Mexico’s relation with the U.S., which has poured funding into anti-drug trafficking initiatives in Mexico. The Merida Initiative, which aims to combat drug trafficking, reform the justice system, and bolster border security, receives around $100 million a year from the U.S. Congress.

De Vos says that while López Obrador’s proposals are a departure from the norm, they could work toward common goals for the region: Improving rule of law could diminish the kind of violence that drives people to migrate north. If Mexico becomes more stable and secure, people “might not be looking [or seeking] to leave” and to enter the United States, he says.

There’s always a possibility, of course, that Mexico’s amnesty policy won’t play well with U.S. politicians. But as with Canada and France, whose leaders have recently suggested U.S. leadership is too volatile to depend on, Mexico may not try to game out a possible U.S. response. “Ultimately, Trump doesn’t particularly care what is happening in Mexico,” says Enciso. “He will continue to be the politician he’s proven himself to be.”

While some media accounts liken López Obrador to Trump due to his populist rhetoric, Mexico’s president-elect is his opposite when it comes to security policy. Going against the grain in the region, López Obrador will seek to counter violence with mediation and reconciliation, instead of militarization and securitization. López Obrador’s resounding victory on Sunday showed that voters were ready for a change, and security policy is no exception. The results will be felt far beyond Mexico’s borders.

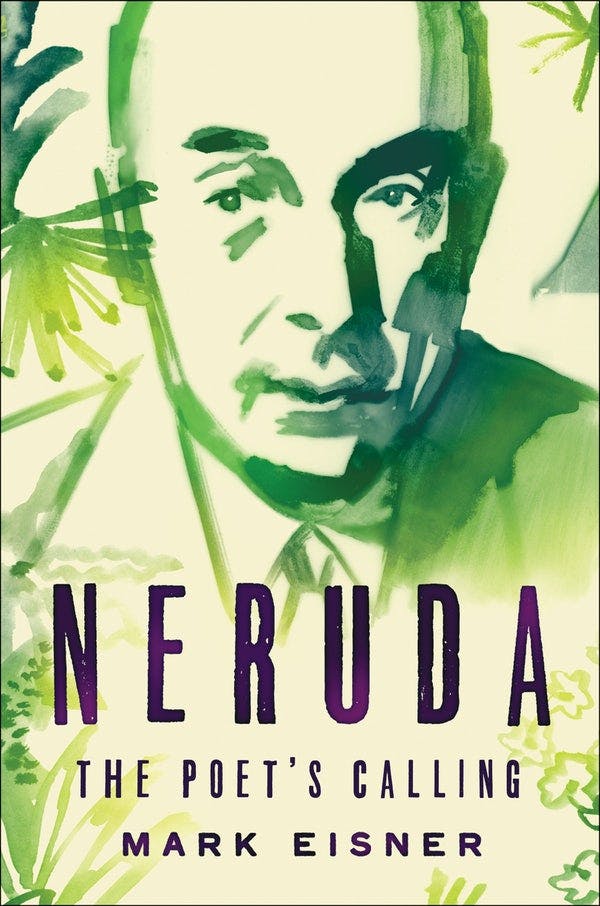

The poet Pablo Neruda was born in 1920 at the age of 16. It was in October of that year, anyway, that a young man whose unsuspecting parents had baptized him Ricardo Eliecer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto first signed with the name Neruda the poems that he felt he existed in order to write. Already, at 15, Neftalí (as his familiars addressed him until he escaped to college in the big city) had described himself, in excited drafts, not just as a poet but the poet, Mark Eisner points out in his new biography, Neruda: The Poet’s Calling. A sonnet titled “The Poet Who is Neither Bourgeois nor Humble” alluded to his potent, unknown poet-ness: “The men haven’t discovered that in him exists / the poet who as a child was not childish.”

Neruda as an adolescent poet amounted almost to a parody of the type, worryingly thin, melancholy and shy, and got up, unlike other local boys, all in black. Sickly and frail, he was unsuited to the physical labor done by most of his neighbors, and, a lazy pupil at school, he did not suggest a country doctor or lawyer in the making. He appreciated the splendors of the natural world and mooned over pretty girls but otherwise showed little aptitude or interest for anything outside of books. Among the men who didn’t recognize his promise was the poet’s own father, a former dockworker with a hard demeanor. Following the death of Neftalí’s mother mere weeks after the birth of her son, he’d installed the family in the frontier town of Temuco, halfway down the racked spine of Chile, where as the conductor of a “ballast train” he oversaw a crew of laborers continuously pouring gravel over the railroad to keep the tracks from being washed away by violent weather.

His father became so concerned that his son would learn no useful trade that he one day hurled the boy’s bookcase and papers out the window, then set them alight on the patio below. Neruda invented his pen name with the aim, he recalled some 50 years later in his Memoirs, of throwing his father “off the scent” of his published poems. Soon after the 17-year-old Neftalí Reyes enrolled at the University of Chile in Santiago, relying on his father for his meager living expenses and neglecting his studies in French pedagogy, one Pablo Neruda began to attract the notice of fellow students as a talented poet. Exotic but easy to pronounce, his adopted Czech surname became that of the preeminent twentieth-century poet in Spanish, a language whose poetry had quite a century.

Neruda said the ordeals of the era invited the poets’ breakthrough. “It has been the privilege of our time—with its wars, revolutions, and tremendous social upheavals—to cultivate more ground for poetry than anyone ever imagined. The common man has had to confront it, attacking or attacked, in solitude or with an enormous mass of people at public rallies.” A more sociological way of framing the idea would be to say that, because mass literacy and education formed a basic aspect of mass politics, poets during the middle half of the twentieth century could both come from humble backgrounds as never before and find an audience among ordinary people as never before. Neruda’s own case seemed to particularly confirm the general observation: Raised in “country-boy, petit-bourgeois” circumstances, “the people’s poet,” as he called himself, could in the decades after World War II fill stadiums and union halls, reciting to mass gatherings poems about the masses’ common pleasures and collective struggle. “A poet who reads his poems to 130,000 people,” he wrote about an occasion in São Paulo, “is not the same man and cannot keep writing in the same way.”

Neruda remains today an unusually popular poet, in utterly changed conditions. If some of his best poetry eludes easy comprehension, he more often produced verse after transparent verse. Even the surreal imagery of the early work can create a sensation of the cloudless transmission of emotion, as young people in love still frequently discover when they encounter their own throes of passion while reading Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair in their beds. (Taylor Swift credits Poem XX with inspiring her quadruple-platinum album Red.) The Elemental Odes that Neruda published in his fifties, during the 1950s, attain a more deliberate universality, as they contemplate the commonest items of human life: air or wine, copper wire or sexual coupledom, as well as sand and scissors and, in “Ode to Simplicity,” simplicity itself. Neruda’s books, said to outsell all other poetry translated into English, are often household articles in their own right.

Part of the value of Eisner’s biography is to situate a lastingly familiar and accessible body of work in its author’s exceptional experience of an irrecoverable recent past. Today the combination of a great poet who was also, in his words, “a disciplined Communist militant,” one of his country’s leading politicians, and an international celebrity is positively antediluvian. The decades since Neruda’s death in 1973—not two weeks after a right-wing coup overthrew the elected president of Chile, the poet’s “great comrade” Salvador Allende—have seen the rout of international socialism as well as a radical shrinkage in the audience, or market share, for poetry. Neruda the earth’s universal poet hails from another planet.

Neruda was just 20 when he published what remain his best-known poems. Old beyond his years and sad beyond any misfortune he’d yet suffered, he wrote in Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair of “mi viejo dolor,” my old sadness. Melancholy is almost obligatory for young male poets; in other respects, Neruda spurned the genteel conventions still prevailing in love poetry of the time. The first lines of the first poem abandon any spiritualized and euphemistic presentation of romance and sex for something carnal and explicit: “Body of a woman, white hills, white thighs, / you look like a world, lying in surrender.” One of the poems’ addressees was Albertina Azócar, another Laura Arrué. The parents of both young women judged a train conductor’s son of unsatisfactory social standing for their daughters. As if to taunt them, he describes his “rough peasant’s body” that “makes the son leap from the depth of the earth.”

NERUDA: THE POET’S CALLING by Mark EisnerEcco, 640 pp., $35

NERUDA: THE POET’S CALLING by Mark EisnerEcco, 640 pp., $35Some of the Twenty Poems became so well known that Neruda was annoyed: In later years he denounced XX (“Tonight I can write the saddest lines”) as the worst thing he ever wrote. The protest is unconvincing. With precocious assurance, the book shows the emotional directness and unabashed musicality that would abide across Neruda’s drastic alternations of style, along with other personality traits, as it were, of a long career. Already there is the offhand metaphorical extravagance, as if it’s merely natural and straightforward to describe oneself as a tunnel or a root, and a pressing awareness of the injuries of class society, the romantic frustrations of poor young men not least among them.

Twenty Love Poems was a critical and even something of a commercial success, but Neruda found himself unwilling or unable to rest on his laurels. In spite of the poems’ frankness they had been conservative in form, consisting largely of rhymed lines of an equal count of syllables. They had also been conversational and urgently communicative: “Now I want [my words] to say what I want to say to you / to make you hear as I want you to hear me.” It may have been precisely the apparent success of his love poems as instances of communication—giving voice to universal experiences of longing, bliss, and loss as if they were the reader’s own—that led Neruda to feel he had been unfaithful to the unhappy isolation of a “soul in despair” that, far more than love, was still the main condition of his life.

His next poems departed from the celebrated mode of Twenty Poems to describe inward states—Eisner writes that Neruda “invented a way to capture how language sounded inside his mind,” prior to the demands of articulation—in obscure imagery and lines of uneven length. Assembled in a volume called venture of the infinite man, the new work met a disappointing and disappointed reception. “The flesh and blood we had admired so much in the author’s other books are missing here,” a prominent reviewer complained, adding that the book might as well be read from back to front. “One would understand the same, that is to say, very little.”

Neruda’s overriding problems in his early twenties, a friend observed, were money, love, and poetry. Of these, poetry was easiest to address, which is not to say solve; for one thing, Neruda could produce it by himself. Love and money, on the other hand, you can only get when others give them. Fiction promised better remuneration than poetry, and Neruda received a small advance to write a thriller. His first and last attempt at a novel “definitely is not one,” Eisner writes, and the nearly plotless succession of moody images achieved about the sales one would expect. Neruda begged his sister, Laura, to convince their father to cough up funds.

When paternal subventions were not forthcoming, Neruda hit on the idea of securing a diplomatic post abroad through Chile’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “In Latin America,” Eisner explains, “especially in the first half of the twentieth century, poets and intellectuals were often named to diplomatic posts, ad honorem, where they could live on a simple salary while working on their craft and acting as emissaries of their country’s culture.” The dream posting was to Paris, capital of world literature and home to various important writers and artists from the Americas. Plus, Neruda spoke the language. A friend in the diplomatic corps duly set up a meeting at the ministry, but when an official ran through a list of capitals in need of Chilean consuls, Neruda could only make out a single name. It was not Paris. “Where do you want to go, Pablo?” he was asked. Neruda—ignorant, embarrassed, hopeful, and desperate—answered “Rangoon” and later located the place on a map.

The dream posting was to Paris, capital of world literature and home to various important writers and artists from the Americas.No writer is more closely identified with Chile—“Neruda is Chile,” Allende would declare—and Neruda felt himself deeply bound up with its tortured geography and political travails, but this was the outset of a highly itinerant life. Neruda appealed to both Albertina Azócar and Laura Arrué to ignore their families’ objections and sail for the Far East as his bride; both turned him down. The journey to Rangoon took him overland to Buenos Aires, where he met Jorge Luis Borges; across the Atlantic to Lisbon, where he celebrated his 23rd birthday; and to Paris, where he met César Vallejo. The thrill of dreamed-of European cities and admired fellow writers was also cruel in its way, since the years that Neruda spent in the Far East would be lonely ones. Posted to Rangoon in the British colony of Burma; then to Colombo, in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka); and finally to Jakarta in Dutch Indonesia, with little in the way of administrative duties at any station, he pursued local women in a manner that Eisner characterizes as predatory.* He dabbled in the society of fellow Westerners but was mainly and essentially alone.

In his solitude, he produced some of the most remarkable Spanish-language writing of the twentieth century. The poems collected under the beautiful title Residencia en la tierra or Residence on Earth—a first volume came out in 1933, a second in 1935, a third in 1947—are often called surrealist, despite being “written, or at least begun,” as Neruda pointed out with some pride, “before the heyday of surrealism,” and the term is apt enough. Smokily elusive of paraphrase, much less interpretation, they project onto the mind’s eye a dissolving succession of images that can seem at once inevitable and inexplicable in the best Surrealist way. “It is a tale of wounded bones, / bitter circumstances and interminable clothes, / and stockings suddenly serious.” The obscure drama in those stockings, and the bathos-cum- pathos of their sudden seriousness, make for one of many hieroglyphs of modern alienation and—Neruda’s coinage—“disaction.”

Sometimes he testifies to the raw passage of time, in the empty extensiveness of space, as if observing a battlefield: “Let what I am, then, be, in some place and in every time, / an established and assured and ardent witness, / carefully destroying himself and preserving himself incessantly, / clearly insistent upon his original duty.” He was dismayed, many years later, to learn that a young man from Santiago had committed suicide beneath a tree with his copy of Residence on Earth open to this poem.

With a dog and pet mongoose (“No one can imagine the affectionate nature of a mongoose”) as his principal companions, Neruda experienced these years mainly as “a demonic solitude,” as he wrote to a friend from Colombo, while waiting out a monsoon. Loneliness seems to have compelled his marriage—the first of three—to a Dutch woman he met in Jakarta. Not yet possessed of the talent he later acquired for making himself and others happy, Neruda started to neglect Maruca, as he called her, soon after they left Asia, and finally abandoned her and their disabled daughter. His Memoirs contain only a single, shamefaced mention of this wife’s name.

Neruda talks to the press in Paris after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971. Laurent Rebours/Associated Press

Neruda talks to the press in Paris after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971. Laurent Rebours/Associated Press Neruda’s life as a poet and a man divides naturally into two periods, so he felt. “The bitterness in my poetry had to end,” he decided, rejecting “the brooding subjectivity of my Veinte poemas de amor, the painful moodiness of my Residencia en la tierra.” From now on his poems would not face inward, toward the isolate individual, but outward, toward “our fellow men”: “I had to pause and find the road to humanism, outlawed from contemporary literature but deeply rooted in the aspirations of mankind.”

This change in attitude, which resulted in his epic poem of the Americas Canto general in the 1940s, began in Spain. Posted to Madrid in 1934, Neruda could enjoy for the first time since college a community of Spanish-speakers and fellow poets, and he often entertained friends and their families in a diplomatic residence, lively with dogs and children, that he and his visitors called “the house of flowers, because it was bursting / everywhere with geraniums.” The Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, whose work Neruda seems to have admired without envy, was his favorite guest.

The idyll ended on July 17, 1936, when a junta led by General Francisco Franco rose up against the Spanish Republic and its Popular Front government. Lorca, gay and left wing, was kidnapped and murdered the next month by Falangists. “The news of his death made everyone cry,” Delia del Carril, later Neruda’s second wife and already by this time his lover, recalled. For Neruda it was the most painful event of the war. He apostrophized his dead friend: “If I could weep with fear in a solitary house, / if I could take my eyes out and eat them, / I would do it for your black-draped orange-tree voice”—Lorca was from Andalusia—“and for your poetry that comes forth shouting.” After Lorca’s death, Neruda uses the word poetry as a name not just for printed words with a ragged right-hand margin but, frequently, for beauty, goodness, joy, life, friendship, community, justice, peace. The enemy of poetry is fascism.

With Madrid under bombardment, Neruda fled for Paris in 1937, where he organized a congress of left-wing writers in defense of the Republic. When the Republic fell, he risked his diplomatic career by commissioning a ship to carry some 2,000 Spanish refugees to asylum in Chile. Warned by his government that this action required its authorization, Neruda threatened to shoot himself unless the Winnipeg sailed, and the Chilean president gave in. On Neruda’s return to his country in 1939, with Europe falling to another kind of fascism, he was greeted on the docks by grateful refugees chanting his name.

It is an uncomfortable and perhaps uncomfortably suggestive fact that this most universal of twentieth-century poets was also a notorious Communist and indeed Stalinist. Something similar can of course be said about many important writers and artists of Neruda’s and adjacent generations: They too joined their countries’ Communist parties or at least fellow-traveled; they too rooted for international socialism against the Nazis in Europe and, later, against the yanquis in Latin America and Indochina. Neruda stands out from most of these artists, whose work, good or bad, typically displayed their political commitments superficially if at all. From the late 1930s or early ’40s onward, Neruda was not incidentally but essentially a Communist poet.

The least of it is that he proudly avows his allegiance in any number of poems. He hymns the Red Army’s triumph in Stalingrad and later writes odes to Stalin and Lenin. Much of this stuff is expectably bad. Neruda, in his unembarrassed prolixity, published mediocre verses on all kinds of subjects political and otherwise, but the “Ode to Lenin” (1957) shows as well as anything how facile and sentimental he could let himself be: “The revolution turns forty. / It has the age of a ripe young woman. / It has the age of the beautiful mothers.” The metaphor would be more thoughtful if he’d wondered how the revolution might look in old age or could surpass a normal life span. As it is, the lines are clever, warm, politely beneficent—toast more than poem, and a reminder of Neruda’s long diplomatic career.

He hymns the Red Army’s triumph in Stalingrad and later writes odes to Stalin and Lenin. Much of this stuff is expectably bad.Some of Neruda’s explicitly committed work, however, is genuinely stirring, at least to this socialist critic. Although Neruda affirmed “my general Marxist principles, my dislike of capitalism and my faith in socialism,” and viewed the USSR as the lodestar of a rising proletarian international, his poetry bears little trace of either a Marxist theory of history or a Leninist politics of revolutionary strategy. His communism is closer in spirit to what Alain Badiou has described as “the communist hypothesis”—a historically intermittent but almost immemorial proposal of universal emancipation. The penultimate poem of Canto general, written in 1949 and addressed to the Chilean Communist Party, which Neruda had joined four years earlier, offers one of many examples. (With Neruda there are always many examples.) A somewhat free translation of a few lines reads: “You have made me brother to the man and woman I don’t know”; “You taught me to see the unity and difference of humankind”; “You have made me see clearly the world and its chance at happiness”; “You have made me indestructible because with you I no longer end in myself.”

In his concern with the suffering of universal or common humanity and in his celebration of the humble common pleasures partaken of by everybody—profane sacraments of weather, landscape, food, drink, sex, love, friendship—Neruda becomes a communist, small ‘c,’ and therefore a Communist in opposing the ancient, ongoing scandal of class society, which betrays the world’s chance at happiness by fracturing the human community into classes and nations, exploiter and exploited, conquistador and conquered.

Unusually for a Communist poet, Neruda also became a Communist politician. The Stalinism for which he’s derided accurately enough describes his orientation to world affairs from the Spanish Civil War until the early 1960s, when he belatedly repudiated the dictator who “administered the reign of cruelty / from his ubiquitous statue.” At home in Chile, however, Neruda was a democratic socialist: The parliamentary route to power represented the only nationally viable strategy. In 1945, he won election to the Senate on the Communist ticket. He represented a pair of northern mining provinces where workers toiling in nitrate mines, beneath the sun-stricken pampas of the driest desert on earth, figured among the most exploited in the world. A century and more after Chilean independence, both the mines and the railways bearing away the yield of the mines remained in British hands. The neocolonial arrangement more or less enraged Neruda.

In 1946, Gabriel González Videla was elected president of Chile with the support of the left. Once in office, González filled with Communists and subversives a concentration camp in the northern port of Pisagua. On January 6, 1948, Neruda denounced President González on the Senate floor in a speech later published under the Zolaesque title “Yo Acuso”: “There is no freedom of speech in Chile”; those “who fight to free our country from misery are persecuted, mistreated, injured, and condemned.” A week later he read out the names of more than 450 political prisoners, until he was cut off; he resumed the next day with 56 more names. On February 3, the Supreme Court stripped Neruda of parliamentary immunity, alleging that he had made false statements against the president, and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

He and Delia hid from the police in a series of comradely households, moving frequently until Neruda was spirited to Patagonia. There the politically unsympathetic owner of a vast ranch showed his decency by loaning horses and men for the trek over the Andes. Neruda escaped Argentina on the passport of a writer who resembled him and flew to Europe. In 1952, the Italian government moved to extradite the fugitive, before reconsidering in the face of public protests and bad press. Neruda the rescuer of refugees and exiled senator, forthright Communist and admired poet, had become international news.

He had put together his beautiful, harsh, partisan, and infuriated book-length poem Canto general over about a decade, from an initial Canto general de Chile begun in 1938 to the completion in 1949 of a general song of all the Americas, from the Southern Cone upward. Bits were composed in Mexico, Peru, at home in “cruel, beloved” Chile, and in flight across the Andean sierra. The historical schema of Canto general (1950) goes something like this: prehistory of the Americas, especially the second Eden of the southern hemisphere; sacking of indigenous South and Meso-America by Iberian empire; liberation from the Bourbon crown in the early nineteenth century and establishment of republics by creole heroes; betrayal of the paradisal continent by local compradors and foreign capital, and emergence of Latin American communism; a summons to the USA to revive the better angels of our nature—Lincoln, Walt Whitman—and join the southern struggle; Neruda’s own fugitive existence, on the run from police; and the prediction or promise that “My people will overcome. All peoples / will overcome, one by one.”

The ghastly vistas of blood and ash that Neruda conjures as he catalogs the genocidal campaigns of Cortés and other conquistadors are often powerful in their simplicity. In what is today southern Mexico, “The solemn river saw its children / die or survive as slaves.” Elsewhere Neruda’s language takes on a rhetorical luxuriance, as in his threnody for the murdered civilization of the Maya. Nor does grief for indigenous victims prevent him from pitying Spanish foot soldiers, their lives wasted on an infamous crime. Short as the individual lyrics are, the howling bill of imperialism is almost unbearable to read more than a few items a time.

Canto general is, as intended, a monument of Western and specifically American literature. As a chronicle of a captive and abused people scheduled for redemption, it recalls the Hebrew Bible; as a historical vision of originary calamity and ultimate deliverance, it brings to mind Paradise Lost; and as a democratic catalogue of New World humanity, it follows Whitman, whom Neruda explicitly invokes. Canto general also looks forward, to Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, where the backwaters of the New World are also the center of creation, or to Eduardo Galeano’s Memory of Fire trilogy, another factual chronicle of conquest and rebellion across the span of Latin American history related with prophetic indignation. Che Guevara carried a copy of Canto general with him in the Sierra Maestra.

For all that, Canto general is often more great than good. Neruda’s gift is lyrical, not narrative, and his ostensible epic, on inspection, is so many lyrics in historically chronological order. Neruda sometimes writes least about what is most important (the best of the 15 sections, “The Heights of Macchu Picchu,” is also among the shortest), and vice versa. And, unsurprisingly, Neruda’s weakest lines are often his most polemical, propagandistic, the poet seeming to say what he should feel or think instead of what he does. None of this much qualifies the glories of the thing. Part III of “Macchu Picchu” concludes, about everyone: “they all faltered on awaiting their brief daily death: / and the bitter brokenness of each day was / like a black cup they drank from trembling.” My translation may improve on some others, but the rills of plangent vowels are lost.

“Sube a nacer conmigo, hermano” is probably the most famous line of the poem: “Rise to be born with me, brother.” History presents a choice, Neruda says, between dying alone each day or being born at last with our brethren. If the notion is embarrassing today, this does not seem entirely to our credit.

Celebrity Communist, champagne Stalinist, poet of the people who owned three houses—the Neruda of his last two decades is easy to make fun of, or worse. Even friends who revered him seem to have smirked. In his memoir of Neruda, Volodia Teitelbaum, a friend and fellow Chilean Communist, reports that the recipient of the 1952 Stalin Peace Prize was, on his many stays in Moscow, often put up at the Metropole Hotel, an establishment much favored under the czar by nobles and rich bourgeois, where Neruda enjoyed “an apartment complete with a pair of grand pianos, enormous bathtubs decorated with purple flowers, and huge emerald-green leaves,” and so on. Neruda’s defense was that nothing was too good for the working class.

Celebrity Communist, champagne Stalinist, poet of the people who owned three houses—the Neruda of his last two decades is easy to make fun of, or worse.At his best, Neruda can express in uncanny images and ordinary words something that feels like the essence of experience. At his worst, he seems to trade in stereotypes of reality. The later poetry, oscillating between the poles of the generic and the universal, favors the generic. During his European exile, Neruda fell for a Chilean folk singer, Mathilde Urrutia, eight years his junior. Even in one of his strongest late volumes, The Captain’s Verses (1952), the imagery seems easy, sometimes evasive. As he relates the ups and downs of their new love, the same elemental lexicon recurs throughout: roots, earth, blood, wheat, stars, thorns, etcetera. Mathilde, “newborn from my own clay,” is a star, or a condor, or a mountain; called “little America,” she has rivers and countries in her eyes, and you wonder how attentively perceived she felt.

In 1952, after a new administration rescinded the warrant for his arrest, Neruda and Mathilde returned to Chile. When she complained of the “piece-of-shit-country,” Neruda reminded her: “This piece-of-shit-country is yours!” His work by now brought in enough money for him to maintain one residence in Santiago and two in the provinces. On a rugged stretch of Pacific coast called Isla Negra—“Ancient night and the unruly salt / beat at the walls of my house”—he built a dwelling after his own design and filled it with specimens of the natural world and souvenirs from his travels. In his later poems, he is above all grateful for being alive, “always / half undone with joy.” A secondary but important mood is the melancholy of old age, of the tardiness of fulfillment.

Material comfort and a happy marriage did not exactly mellow him. The title of one late volume is Invitation to Nixonicide and Glory to the Chilean Revolution. In a substantial poem called “The People,” he reiterates his desire to see, for the first time in history, the poor man “properly shod and crowned.” As the Communist candidate for president of Chile in 1970, Neruda promised to support the Socialist Allende in the final round and, in spite of failing health, campaigned energetically for his comrade at rallies where he also recited his poems. Three years later, General Pinochet and his accomplices—with CIA assistance, and aided by a sustained U.S. campaign of economic sabotage—ended at gunpoint Chile’s experiment in parliamentary socialism. Mere days before Neruda succumbed to cancer (unless—forensic investigators have not quite settled the question—he was poisoned by the new regime), he and Mathilde saw the presidential palace in flames on television and tanks in the streets of the capital. A fascism not unlike what destroyed the Spanish Republic had seized Chile.

In spite of his intelligence and wit, his transformations and peregrinations, Neruda was, or learned to be, a simple man. His relationship to food suggests something of this. When he was young and poor, he didn’t get enough to eat, often consumed his rations alone, and was very skinny; when he was older and prosperous, he had plenty to eat and became portly. The desire was constant, the fulfillment was not. Similarly, he wanted his fill of friendship, love, and sex. Who does not? After a disconsolate youth, communism bestowed purpose on his life and work, his own happiness granted in large measure by the proposition that happiness could become a universal possession—a staple, not a delicacy. But he died in anguish, saying again and again in his delirium, “They’re shooting them!”

* This piece has been updated to reflect the nature of Neruda’s relationships while on diplomatic postings in Asia.

The late Harlan Ellison, whose death at age 84 was announced on Thursday, was famously touchy about criticism. But no critic did as much damage to the writer’s reputation as he himself did. Despite having recieved many awards for his science fiction and fantasy stories, his reputation suffered, particularly toward the end of his life, from his mercurial and sometimes violent temper, which led to transgressive and criminal behavior. In 2006, he humiliated writer Connie Willis by groping her breast on stage during the Hugo Awards. Ellison claimed that the act was a joke and apologized, but it fit in with a larger pattern of boundary-crossing he boasted in other contexts.

In 1980, Ellison bragged about attacking ABC Television executive Adrian Samash sixteen years earlier for altering the script Ellison wrote for Vogage To the Bottom of the Sea. “I tagged him a good one right in the pudding trough and zappo! over he went… windmilling backwards, and fell down, hit the wall,” Ellison said. The encounter left Samash with a broken pelvis. In 1985 at the awards dinner of the Science Fiction Writers of America, Ellison punched fellow writer Charles Platt, who had criticized Ellison for a speech he felt was tasteless.

Ellison’s violence and sexual assault tainted his reputation while he was still alive; and now, they continue to raise questions about how to evaluate his work. In a measured obituary last week, science fiction writer Cory Doctorow struggled with how hard it was to balance the respect he felt for Ellison’s work and the loathing he had for some of Ellison’s actions.

“Confronting the very real foibles of the object of my hero-worship was the beginning of a very important, long-running lesson whose curriculum I’m still working through: the ability to separate artists from art and the ability to understand the sins of people who’ve done wonderful things,” Doctorow wrote. “These are two questions that have never been more salient in the age of #metoo, and I often ponder this journey I’ve gone through in my views on Ellison since my adolescence.”

Ellison’s death is a natural time to attempt to answer those two questions: to take the measure of his legacy by reexamining his life and work.

One of Ellison’s last short story collections was The Top of the Volcano, a gathering of his award-winning tales. The title was apt: Ellison was a volcanic writer and public presence—loud, furious, fire-spewing, sometimes dangerous, always impossible to ignore. He was a contentious figure who generated heated arguments wherever he went, but by dint of his energy and passion helped change American science fiction and fantasy; He transformed the genres from their pulp coloration of the early 20th century into fields of high literary ambition.

He was born in Cleveland in 1934, and grew up in the small town of Painesville, where he was often a victim of anti-Semitic bullying. He often credited his resilient and contrarian personality to the thick skin he developed as a result of youthful torments. He found escape in science fiction, not just as reading material but also in the sociability of its active fandom. As a teen, he was already editing science fiction fanzines and forming friendships with future writers, most notably Robert Silverberg, who would be his life-long pal.

He dropped out of the Ohio State University in 1953, with what he boasted was the lowest grade point average in the school’s history, and became a writer for pulp magazines. He wrote garish tales in many genres (including soft-core pornography) for publications like Infinity Science Fiction, Terror Detective Story and Exotica.

In general, Ellison is a writer whose readership leans heavily on people who read him as a teen and often outgrew him.Little of his early work is worth remembering, but the pulps gave him an education in storytelling that would help him when he moved to Los Angeles in 1962 and became a TV and screen writer. Although he often quarrelled with producers, he made a name for himself in that field, most memorably by writing “The City on the Edge of Forever,” which is widely considered to be the best episode of the original Star Trek series.

The economic security he gained from writing for television allowed him to reinvent himself as a fiction writer in the 1960s. His prose became more energetic and visceral. The best of these stories—“The Deathbird,” “Jeffty is Five” —were much anthologized. His tale “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore” was included in The Best American Short Stories collection for 1993, an achievement that particularly pleased Ellison as a sign that he was read outside what he saw as the ghetto of genre fiction.

To be sure, even in his best work, Ellison was a limited writer with a narrow emotional and tonal range. He could do rage, terror, and alienation very well, with hectoring and loud stories that mirrored the 1960s countercultural rage at the establishment. But there was little in Ellison’s work of empathy, friendship or love. He had no gift for conveying delicate shades of feeling. It’s not surprising that Doctorow speaks of loving Ellison’s work as an adolescent. In general, Ellison is a writer whose readership leans heavily on people who read him as a teen and often outgrew him. As Tim Hodler of The Comics Journal noted, Ellison “was a perfect writer to discover in middle school or junior high.”

More important than Ellison’s own work was the encouragement he gave to other writers through his editing and mentorship. Ellison’s didn’t just push himself to improve as a writer, he did the same for the genres he was most closely affiliated with. He edited two of the most influential anthologies in the history of science fiction: Dangerous Visions (1967) and Again, Dangerous Visions (1973). A third volume, The Last Dangerous Visions, went unpublished even though Ellison had gathered scores of stories.

The selling point of these books was that they featured taboo-breaking stories, a popular way to market books in the counterculture era. But the true innovation was the high literary standards Ellison demanded of his writers. Along with fellow editors Judith Merrill and Michael Moorcock, Ellison played a crucial role in pushing science fiction and fantasy writers to abandon the blood-and-thunder prose of the pulps and write with greater tact and flare.

Many of the writers Ellison encouraged and promoted—including Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel Delany, J.G. Ballard, and Octavia Butler—became major figures in world literature. To Butler in particular Ellison was an important mentor. Unlike Ellison himself, these writers achieved a crossover success with a general audience. They weren’t just anthologized once or twice in prestigious mainstream publications, but rather won a more lasting name among fiction lovers.

Ellison’s quarrelsome personality clouded his reputation. He was quick to get into feuds and lawsuits. A dust-up Ellison had with Frank Sinatra is immortalized in a classic Guy Talese article. Sometimes he had justice on his side, as when he rightly claimed the film The Terminator was plagiarized from his work. (Ellison achieved a settlement with the film’s producers, so the debt The The Terminator has to his work is now acknowledged in the credits.) But often he did not. For example, his 2006 lawsuit against Fantagraphics, a vital independent publisher specializing in graphic novels, seems to have been frivolous and motivated by personal malice. A settlement was reached but the suit carried the real risk of destroying Fantagraphics.

Ellison’s death is an opportunity to disentangle his personal flaws from his lasting achievement with the aid of historical perspective. His macho bluster now seems a period piece—influenced by Ernest Hemingway and Nelson Algren, and paralleled by the antics of Ellison’s contemporaries like Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson.

Ellison’s push to make science fiction more literary was a victorious crusade, although other writers who made the same journey proved better equipped to write lasting books that blurred the line between fantastika and modernism. His best work—found in the collections Deathbird Stories (1975) and Shatterday (1980)—will live on as examples of superior young adult fiction. His personal violence remains unforgivable.

No comments :

Post a Comment