Andrew Gillum wasn’t expected to win Tuesday night’s Democratic primary for the Florida governor’s race, even after he won Senator Bernie Sanders’s endorsement weeks ago. The 39-year-old Tallahassee mayor was outspent five-to-one by the frontrunner, and even more so by the two billionaires in the race, but he triumphed nonetheless—a key victory for the insurgent progressive wing of the Democratic Party. If he prevails in November, Gillum would be only the second black governor in the South since Reconstruction and Florida’s first Democratic governor since 1999.

In his victory speech, Gillum highlighted an issue that’s received short shrift from Florida policymakers in recent years. “Beneath my name is also a desire by the majority of people in this state to see real criminal-justice reform take hold,” he told a crowd of supporters at his Tuesday night victory rally. “The kind of criminal-justice reform which allows people who make a mistake to be able to redeem themselves from that mistake, return to society, have their right to vote, but also have their right to work.”

The message could apply anywhere in the United States. But it carries greater resonance in Florida, which ranks among the most carceral states in the union. While crime has plummeted nationwide since the early 1990s, Florida’s prison population hasn’t seen significant declines. Instead, the number of people serving more than ten years in prison tripled between 1996 and 2017. Lawmakers abolished parole for most crimes by 1993, which requires the state to keep many prisoners behind bars who don’t pose a danger to society. Even today, the state has shirked the broader reform-oriented trend on both the left and the right.

Gillum has campaigned on a platform that could change that. His campaign’s official site touts measures similar to those adopted in some Democratic-led states, like reducing the number of crimes that carry mandatory-minimum sentences and reforming the cash-bail system, which disproportionately harms lower-income Americans. Others are more bold: Gillum went further than his primary opponents and called for the full legalization, rather than just decriminalization, of marijuana. Though he told reporters he is not an opponent of the death penalty, Gillum said he would suspend executions to address concerns about racial disparities.

Florida may already be the most important battleground of the 2018 midterms. Bill Nelson, the state’s Democratic senior U.S. senator, is facing a strong challenge from Rick Scott, the incumbent governor, that could help decide control of the Senate. Eight of the state’s 27 congressional districts are currently considered to be competitive House races by the Cook Political Report. With Gillum as the Democratic nominee for governor, facing off against a Trumpist Republican nominee in U.S. Congressman Ron DeSantis, November’s elections will also be a referendum of sorts on criminal justice reform.

Nearby states with high prison populations have already taken steps to alleviate the problem in recent years. Texas’s incarceration rate has steadily declined since 2007 after lawmakers expanded diversion programs and drug courts. In April, Mississippi adopted changes to prevent people from automatically being sent to jail if they are unable to pay fines and court fees. Georgia Governor Nathan Deal signed a package of reforms into law in May that reduces punishments for low-level drug offenses, lowers the felony theft threshold, and sets aside funding for diversion courts.

Florida has bucked the reformist trend, however. In 2018 alone, state lawmakers rejected bills that would have given judges more discretion in sentencing for low-level crimes, reworked the state’s felony theft laws to prevent disproportionate sentences, created an oversight board for Florida’s correctional system, and reduced penalties for people with non-violent drug convictions. The legislature ultimately approved modest changes to the juvenile-justice system and a measure to improve criminal-justice data collection. But those efforts fall far short of what Florida’s neighbors already managed to enact.

State officials have also aggressively defended some of the system’s worst features. In February, a federal judge struck down Florida’s felon-disenfranchisement system for violating the First and Fourteenth Amendments. Florida is one of a handful of states that imposes a lifetime ban on voting for people with felony convictions after they complete their sentence. Those rights can only be restored by appeal to a panel selected by the state’s governor that rarely approves the requests.

As a result, more than 1.5 million Floridians who are otherwise eligible to vote can’t cast a ballot, warping the state’s electorate. (Gillum’s brother, he says, is one of them.) Scott persuaded the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals to stay the judge’s ruling while legal proceedings continue, leaving it intact for the 2018 midterms. But the legal fight may soon be moot: Florida voters will consider a constitutional amendment this fall that would eliminate felon disenfranchisement for all but murders and serious sexual offenses, which would restore full civic rights to hundreds of thousands of the state’s residents.

Other Democratic gubernatorial candidates have also called for sweeping criminal-justice in their states. Georgia’s Stacey Abrams, who would be the first black woman governor ever elected in America, grounds her approach in the experience of her brother Walter, who has bipolar disorder and developed a drug addiction. Instead of receiving treatment, he and tens of thousands of other Americans with major mental illnesses are regularly churned through the criminal justice system for committing crimes of survival like petty theft. Abrams’s platform focuses on improving alternatives to incarceration and bolstering reentry programs to improve the transition back into society.

Maryland’s Ben Jealous, a former president of the NAACP, would go even further. His platform calls for the full legalization of marijuana, the abolition of cash-bail programs, shifting the state’s parole powers away from the governor’s office and toward independent experts, and expunging criminal records for certain crimes to aid reentry and employment efforts. Among his more significant proposals is a state program to investigate prisoners’ claims of innocence. A commission dedicated to that task in North Carolina secured eight exonerations in its first nine years of existence.

A constant fear among reformers is that the political winds could turn back toward tough-on-crime policies after years of favorable weather. It’s unclear whether that will be a problem in Gillum’s contest against DeSantis. Many GOP elected officials have thrown their weight behind criminal-justice reform to varying degrees in recent years, though it’s unclear if DeSantis counts himself among them. His threadbare campaign issues page doesn’t discuss the issue and his campaign staff hasn’t provided details on the matter to local media outlets. Like Trump, though, he has run as a law-and-order candidate, and seems more likely to emulate the president’s attack on Gillum as a supposed enabler of crime:

Not only did Congressman Ron DeSantis easily win the Republican Primary, but his opponent in November is his biggest dream....a failed Socialist Mayor named Andrew Gillum who has allowed crime & many other problems to flourish in his city. This is not what Florida wants or needs!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 29, 2018In 2015, while serving as Tallahassee’s mayor, Gillum pushed for the city commission to join a ban-the-box initiative when hiring government employees. The nationwide campaign aims to change when employers learn about a prospective candidate’s criminal background. Supporters of the initiative, which range from the ACLU to the Koch brothers’ political advocacy network, argue that it helps people with criminal convictions reenter society and rebuild their lives. Gillum defended the effort on similar grounds against critics who claim that it gives former prisoners amounts to special treatment.

“It is instead about giving people a fair shot on how they are evaluated on their skills and capabilities,” he wrote in an op-ed. “It is about changing the sequence of how the city vets candidates for employment, and the meaningful conversations we can have with people who have paid their debt to society. This is also about giving people the chance to move on with their lives and become responsible and contributing members of their community.” The commission approved the measure on a 3-2 vote.

At a White House dinner with roughly 100 evangelical leaders on Monday, President Donald Trump warned of trouble to come if the Democrats win control of Congress in the November midterms. “You’re one election away from losing everything that you’ve got,” he said. “They will overturn everything that we’ve done and they’ll do it quickly and violently. There’s violence. When you look at Antifa and you look at some of these groups—these are violent people.” But his remarks, first reported by The New York Times, also contained a noteworthy canard: that he got “rid of” the Johnson Amendment, which prohibits churches—and any other 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations—from endorsing political candidates.

In truth, Trump has not, and cannot, get rid of that law; repealing it would require an act of Congress, which has failed to do so. Trump is likely making the claim based on an executive order, which many consider to be legally meaningless, urging the Treasury Department to be lenient with religious organizations. His lie, then, raises a familiar question for white evangelicals, who form Trump’s most consistent base of support: What have they really gotten from him?

To answer that question, many would point to Neil Gorsuch’s presence on the U.S. Supreme Court, and to Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to replace Anthony Kennedy. Gorsuch’s confirmation did thrill evangelicals, and though Kavanaugh reportedly told Senator Susan Collins that he believes Roe v. Wade is “settled law,” evangelical leaders have largely fallen behind the campaign to get him on the bench. Evangelicals also have reason to celebrate Jeff Sessions’s tenure as attorney general. He rescinded an Obama-era memo protecting transgender people from workplace discrimination, and launched a “religious liberty task force” to counter a “dangerous movement, undetected by many but real, [that] is now challenging and eroding a great tradition of religious freedom.”

At the same time, Trump’s inability to repeal the Johnson Amendment illustrates the limitations of his promises. He can’t give evangelicals everything they want—and they haven’t been consistently pleased by his performance, either. Some have criticized the administration’s immigration policies. Franklin Graham, one of Trump’s most prominent evangelical surrogates, said the deportations of Iraqi Christians were “very disturbing” and called the family separation policy “disgraceful.” Eight evangelical leaders also wrote a letter to the president urging him to reverse his “zero tolerance” policy and “to resume a robust U.S. refugee resettlement program.”

Many have accused Trump’s evangelical supporters of hypocrisy, for supporting him despite his alleged affairs and cruel immigration policies. But the idea that white evangelicals are hypocrites for sticking with Trump presupposes that they’re so blinded by the prospect of either repealing Roe v. Wade, or weakening the ruling to death, that they allow Trump to play for them for fools. In reality, the evangelicals who walked into the State Dining Room on Monday likely did so because they believed the president really had axed the Johnson Amendment. They probably didn’t even believe his other outlandish claim: that more people are saying “Merry Christmas” now that he’s president. Rather, their attendance reflects more pragmatic motivations.

Evangelicals have regained influence in the White House, and they intend to keep it. The Christian right, after all, is an accomplished political body. If its leaders still back Trump, it’s not because they’re dupes. Rather, they’ve made a series of calculated political decisions—ones that may appear to be in conflict with their religious convictions, but which actually are in line with an overarching political agenda.

The real key to grasping the persistence of white evangelical affection for Trump can be found in his headline-making warnings about the midterms—that the conservative agenda would come under political attack, and that conservatives would come under physical attack, too. “The level of hatred, the level of anger is unbelievable,” he said. “Part of it is because of some of the things I’ve done for you and for me and for my family, but I’ve done them,” he said. The solution, he continued, was for evangelicals to vote in the midterms with their customary enthusiasm: “This November 6 election is very much a referendum on not only me, it’s a referendum on your religion, it’s a referendum on free speech and the First Amendment.”

Evangelicals aren’t strangers to such rhetoric. Their leaders have invoked a fear of physical violence to bolster their claims to spiritual and cultural persecution. Graham warned in 2015 that the U.S. Supreme Court’s impending decision on same-sex marriage would set “the stage for persecution of believers committed to living by the truth of God’s Holy Word.” Another Trump ally, Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council, made comparisons to the Holocaust after the Colorado Civil Rights Commission ruled against a baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. “I’m beginning to think, are re-education camps next? When are they going to start rolling out the boxcars to start hauling off Christians?” he said in 2014.

Evangelicals have often overlooked politicians’ personal failings. We remember President George W. Bush for his religious fervor now, but when he ran for president in 2000, the purity of his faith wasn’t so clear. He was open about his past as an alcoholic, and some wondered if his public conviction just superficially pandered to evangelical whims. “Even people who know Mr. Bush are not always sure how much issues are shaped by his conscience and how much by the political calculation that this White House has refined to high science,” Bill Keller mused in a column for The New York Times in 2003.

In return for their support, Bush empowered evangelicals and marshalled the state’s power in support of their pet causes: He pumped funds into abstinence-only sex education; re-imposed the global gag rule, which bans federally-funded international non-governmental organizations from even informing beneficiaries about abortion and contraception; and launched a faith-based initiatives program that provided federal funds to religious bodies that provide social services.

The discrepancy between Trump’s personal life and his public piety is more pronounced than any apparent discrepancy during the last Bush presidency. But evangelicals hedged the same bets during both Republican presidencies. Bush said the right things, and backed them up with substantive policy often enough to mollify them. Similarly, the accuracy of Trump’s specific claims ranks below his acquiescence on a more important point. Trump thinks there’s a war on, and casts it in terms evangelicals recognize. It’s a war they intend to win.

Some years ago, I had a colleague who would frequently complain that he didn’t have enough to do. He’d mention how much free time he had to our team, ask for more tasks from our boss, and bring it up at after-work drinks. He was right, of course, about the situation: Although we were hardly idle, even the most productive among us couldn’t claim to be toiling for eight (or even five, sometimes three) full hours a day. My colleague, who’d come out of a difficult bout of unemployment, simply could not believe that this justified his salary. It took him a long time to start playing along: checking Twitter, posting on Facebook, reading the paper, and texting friends while fulfilling his professional obligations to the fullest of his abilities.

The idea of being paid to do nothing is difficult to adjust to in a society that places a high value on work. Yet this idea has lately gained serious attention amid projections that the progress of globalization and technology will lead to a “jobless” future. The underlying worry goes something like this: If machines do the work for us, wage labor will disappear, so workers won’t have money to buy things. If people can’t or don’t buy things, no one will be able to sell things, either, which means less commerce, a withering private sector, and even fewer jobs. Our value system based on the sanctity of toil will be exposed as hollow; we won’t be able to speak about workers as a class at all, let alone discuss “the labor market” as we now know it. This will require not just economic adjustments but moral and political ones, too.

One obvious solution would be to separate income from labor altogether, a possibility that two recent books tackle from radically different angles. Give People Money, by journalist Annie Lowrey, offers a measured, centrist endorsement of Universal Basic Income—the idea that governments should give everyone a certain amount of cash each month, no questions asked. The anthropologist David Graeber posits that the link between salaried positions and real work has long been tenuous in any case, since many highly paid jobs serve little purpose at all. In Bullshit Jobs, he tries to make sense of the peculiar yet all-too-common situations in which people are hired, after much fanfare, to do a job, then find themselves not doing much—or worse, performing a task so utterly pointless that they might as well not be doing it.

In the absence of a truly useful job, most people, Graeber considers, would be better off living on “free” money. Lowrey views UBI less as a way to eliminate useless work than a way to compensate invisible forms of labor, such as caring for a relative or doing housework, or to bolster underpaid workers. Cash transfers, she proposes, could also stimulate entrepreneurship and creativity. Either way, the idea of paying people just for being alive is now one that both a radical scholar and a reasonable Beltway journalist can take seriously—though neither author fully reckons with the social reordering that would arise from a world organized around love and leisure, not labor.

Graeber’s book expands on his viral 2013 essay “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs,” in which he took aim at “employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.” Eric, who worked as an “interface administrator” at a design firm, found himself in such a job. His responsibility was to make sure the company’s intranet system worked properly, which sounded useful enough. But, it turned out, he was set up to fail. None of the employees used the system because they were all convinced it was monitoring them. It had been designed with the worst, buggiest software. A confluence of office politics and poor management had led the company to hire Eric, who had no experience working with computers. He was to oversee a system that was never supposed to work in the first place.

BULLSHIT JOBS: A THEORY by David GraeberSimon & Schuster, 368 pp., $27.00

BULLSHIT JOBS: A THEORY by David GraeberSimon & Schuster, 368 pp., $27.00Eric ended up doing little. He kept irregular hours and explained to the odd employee how to upload a file or find an email address. He started drinking one, then two, beers at lunch; reading novels at his desk; learning French; and taking trips for nonexistent “business meetings.” If this sounds idyllic—a salary with no work and boozy lunches!—Eric didn’t experience it that way. Instead, he acutely felt “how profoundly upsetting it was to live in a state of utter purposelessness.” Graeber suggest two reasons for Eric’s despondency. One concerns social class: The first person in his family to go to college, Eric wasn’t expecting the white-collar world to be such, well, bullshit. Another reason is existential: When faced with it, “there was simply no way he could construe his job as serving any sort of purpose.”

By Graeber’s metric, my old gig wasn’t quite bullshit, mainly because I rather enjoyed it and found it meaningful. The term is subjective: If someone thinks a job is pointless, it probably is. There are also many repetitive, grueling, or boring jobs that do not qualify as bullshit because they meet an essential need: If a cleaner or bus driver doesn’t report for work, it hurts other people. (These Graeber terms “shit” jobs.) His method for identifying bullshit is, by his own account, unscientific. He draws from a pool of anecdotes to produce an anatomy of bullshit workers, who fall into five categories: “flunkies,” “goons,” “duct-tapers,” “box tickers,” and “taskmasters.”

“Flunkies” are the modern equivalent of feudal minions who make bosses feel big, important, and strong. Whereas they were once doormen and concierges, they now tend to be receptionists who do little besides answer cold calls and refill the candy bowl, or personal assistants who drop off their boss’s dry cleaning and smile when he walks through the door. “Goons” essentially bully people into buying things they don’t need: Marketing managers and PR specialists do this, as do telemarketers. “Duct-tapers” are employed to fix things that aren’t or shouldn’t be broken or do tasks that could easily be automated—data entry, copying and pasting, photocopying, and so on. “Box tickers” help companies comply with regulation (or offload responsibility for complying), and finally “taskmasters,” or middle managers, spread more BS by assigning it to others.

How many of us could stand to work half as much as we currently do without any significant consequences?“The creation of a BS job,” one manager tells Graeber, “often involves creating a whole universe of BS narrative that documents the purpose and functions of the position as well as the qualifications required to successfully perform the job, while corresponding to the [prescribed] format and special bureaucratese.” She explains that her organization’s bureaucracy created odd incentives to retain employees whose work was inadequate. It was easier for her to hire someone in a new position than to fire and replace the incompetent employee. This, she notes, helped BS jobs proliferate.

Graeber attempts to quantify just how much—and after some back-of-the envelope calculations, he wagers that 37 to 40 percent of all office jobs are “bullshit.” He further contends that about 50 percent of the work done in a nonpointless workplace is also bullshit, since even useful jobs contain elements of nonsense: the pretending to be busy, the arbitrary hours, the not being able to leave before five. “Bullshitization” is even infecting the most nonbullshit professions, with teachers overloaded with administrative duties that didn’t use to exist and doctors forced to deal with paperwork and insurance firms that probably should be abolished.

There’s no sure way to verify Graeber’s estimates, but for white-collar workers, they seem basically right. Work backward: How much activity on social media takes place during work hours? How many doctor’s appointments, errands, and online purchases occur between nine and five? In other words, how many of us could stand to work half as much as we currently do without any significant consequences? And yet we insist over and over that we are terribly, endlessly busy.

This state of affairs seems to defy not just human reason, but also basic capitalist logic: Wouldn’t a profit-seeking organization tend to cull unnecessary compensated labor rather than encourage it? Graeber proposes that there is an explicitly irrational reason why such jobs exist—a system he calls “managerial feudalism,” wherein employers keep adding layers and layers of management so that everyone can feel their job is important or at least justified. (They’re “mentoring” young people. They’re helping others develop careers!) The bigger the staff, the more important the company and its leaders feel, regardless of purpose or productivity.

There might be something refreshing about the fact that capitalism has not yet gained full control over its means and ends, and that there are millions of people sitting around getting paid to do nothing all day. Graeber doesn’t buy it. On the contrary: He considers bullshit jobs to be a profound form of psychological violence, a scourge that’s fueling resentment, anomie, depression, and apathy. Patrick, an employee of a student union convenience store, mostly agrees with this judgment. He didn’t mind the work itself; what he resented was being assigned inane busywork, like rearranging things, after he’d finished his tasks six times over. “The very, very worst thing about the job was that it gave you so much time to think,” he tells Graeber in an email:

So I just thought so much about how bullshit my job was, how it could be done by a machine, how much I couldn’t wait for full communism, and just endlessly theorized the alternatives to a system where millions of human beings have to do that kind of work for their whole lives in order to survive.

Of course, some people can escape by focusing on creative pursuits during the hours they are idle. And it helps if everyone in said job acknowledges, if tacitly, that they serve no purpose by being there. But that’s hard, too, Graeber argues, because of the structure and nature of the modern workplace: the rules, the conventions, “the ritual of humiliation that allows the supervisor to show who’s boss in the most literal sense.”

The existence of bullshit jobs has, further, led to the devaluation of vital occupations. Workers in essential, nonbullshit jobs are constantly told by moralizing politicians that their work is noble and that they ought to be grateful for the often low pay they receive. Even though the middle managers and box tickers of the world can console themselves with the thought that they are “generating wealth” and “adding jobs” by virtue of their “economic output,” they secretly envy the real, human sense of purpose that useful workers—teachers, garbage collectors, care workers—share, Graeber writes, and end up vilifying them out of “moral envy.” This impulse plays out politically: Nurses, teachers, and bus drivers, for example, are constantly portrayed as “greedy” when they bargain for better union contracts, or they’re said to be “stealing” from the state when they make overtime wages. When voters in bullshit jobs hear these words over a campaign season, it can swing legislative bodies to the right.

Would it be better if those workers stuck in bullshit jobs could simply walk away? Graeber isn’t one for policy recommendations, but he does float UBI as a potential salve to our sad professional predicaments. A UBI would “unlatch work from livelihood entirely”: If, guaranteed enough money to live on, people could choose between bullshit or nothing, he wagers that they’d choose nothing and do something more useful and interesting with their time instead.

In Give People Money, Annie Lowrey is less concerned with dissatisfied professionals than with some of the world’s poorest (including those in the United States), who in addition to already being overworked and underpaid—if they are employed at all—will likely face the harshest economic consequences if or when menial tasks are automated. These workers are already up against weakened unions, corporations dead set on extracting maximum value from their workforces by scaling back benefits and slashing wages, the rising costs of education and health care, and other trends that wind up concentrating wealth at the very top. When the robots come, as Lowrey believes they will, there’s little that governments, companies, or other organizations can do to make them go away. The best shot for these people, she comes to believe, is unconditional money.

Lowrey makes a convincing moral argument for UBI, insisting that “every person is deserving of participation in the economy, freedom of choice, and a life without deprivation—and that our government can and should choose to provide these things.” She also points out to great effect the destructive moralizing that Americans, at least, attach to money. “We believe there is a moral difference between taking a home mortgage interest deduction and receiving a Section 8 voucher,” she writes, in a refreshing moment of indignation. “We judge, marginalize, and shame the poor for their poverty.” Gaining support for UBI would mean persuading people to reject those assumptions; convincing a majority to see, as Graeber and Lowrey both urge, that commanding a high salary doesn’t automatically make you a good person.

A further challenge for advocates of UBI today is the lack of definitive, long-term surveys “proving” the mechanism’s efficacy: There have been no truly universal cash transfers within one country for an extended period of time, and there are thus no narratives to follow or macroeconomic conclusions to draw. Thanks to increased interest in the phenomenon, though, there are more and more smaller-scale studies, and Lowrey visits one of them in Kenya with GiveDirectly, a charity that essentially hands out cash through mobile payments in poor places. There she meets a man named Fredrick Omondi Auma, who “had been in rough shape when GiveDirectly knocked on his door: impoverished, drinking, living in a mud hut with a thatched roof. His wife had left him,” she writes. “But with the manna-from-heaven money, he had patched up his life and, as an economist might put it, made the jump from labor to capital.”

More money, Lowrey reports, turns the villagers into good capitalists who invest their savings in education and supplies, start businesses, and help grow the local economy. Her observations recall the breathless and somewhat naïve boosterism that surrounded microcredit programs in the late 1990s and early 2000s. She even meets three sister-wives who plan to pool their funds and create a small bank to lend to women. In the United States, too, she finds clear-cut potential for success. In separate chapters, she illustrates the promise of cash transfers for the American poor with more clarity and purpose, visiting a family with disabled children and speaking to women whose jobs just don’t pay enough for them to get by. Simple cash could help teenagers finish school instead of working to support their families; it could adequately compensate women who stay home to care for sick loved ones; it could spare the elderly or disabled from the bureaucratic hell of waiting in line to plead for meager welfare benefits.

Ending poverty around the world ought to be a priority, and Lowrey makes a strong case that unconditional cash transfers can help do that. But in the wrong hands, a UBI can do more harm than good. It can serve as a pretext to further decimate social programs and put more blame still on the individual for any mishaps or shortcomings. As Lowrey notes, libertarians love the idea that UBI could replace the welfare state, shrinking big government—a move that could render the whole program ineffective, since it’s hard to imagine a UBI stretching to cover market-rate housing and exorbitant private health care. Meanwhile, cash payments can also reinforce social and racial divisions by throwing money at a problem without addressing its causes. Giving the individual residents of an over-policed neighborhood cash transfers won’t, for instance, make them any less susceptible to unreasonable searches or violence.

That’s why it matters who supports UBI and, more significantly, whose policies it gets attached to. Many of the people funding UBI research or advocating for cash transfers—Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes and Y Combinator’s Sam Altman, to name just two—are in fact among those who do best from the current distribution of wealth. A UBI would, after all, benefit corporations: For any company that depends on people having money to buy their products—whether groceries, prescription drugs, or driverless cars—the idea of a jobless, incomeless population presents a threat to its bottom line. Free money lets consumers stay consumers; it maintains the current system. And that’s without getting into the possibility that unemployment and poverty might add up to riots, class war, and mass unrest. In that situation, the CEOs would be the first to go.

Both Graeber and Lowrey struggle with the fact that—for all work’s miseries and for all the promise of UBI—work is deeply ingrained in American society. While many of us might hate our individual jobs, most of us love the idea of a job. Our world is constructed around the idea that a job is not just a paycheck: It’s a status symbol and a form of social inclusion. This, of course, supports the creation of bullshit jobs, which prop up the socioeconomic status quo. Now that a jobless (or less job-full) future may be within reach, the question is how to reimagine our relationship with work.

Our world is constructed around the idea that a job is not just a paycheck: It’s a status symbol and a form of social inclusion.Lowrey appreciates the extent to which people identify with their work—even if it’s bullshit or shit (in her parlance, “crummy”) work. Having reported extensively on the psychological toll that unemployment can take, she insists that the culture (or is it cult?) of work is most likely here to stay. It might not be the healthiest approach—she dislikes moralizing around the virtue of work almost as much as Graeber does—but she realizes it’s something we have to build in to our short- and medium-term expectations because “the American faith in hard work and the American cult of self-reliance exist and persist, seen in our veneration of everyone from Franklin to Frederick Douglass to Oprah Winfrey.”

For his part, Graeber insists that there’s no value in working for the sake of just working. That often gives the impression that anyone who does want to work for work’s sake must be a bit of a sucker and that the compulsion to work is a manifestation of false consciousness or, worse, stupidity. He thus glosses over the strongly felt benefits, be they professional, social, or psychological, that many people get from their jobs. If Graeber’s unscientific assertions about bullshit jobs feel vital, urgent, and intuitively true, his dismissals of work’s inherent value—not moral, but social—feel incomplete.

With a compulsion to work so deep-rooted, UBI is a solution that will only go so far, even if implemented in a way that truly does alter lives for the better. Giving people money will not make us less moralistic about labor: People used to working will not necessarily know what to do with themselves or with their time. (I certainly wouldn’t.) Such measures represent only a fraction of the socioeconomic overhaul that will be needed to deal—if not now, then for future generations—with this twin utopia-dystopia: a world with less work and less money.

A solution that neither Lowrey nor Graeber spends much time dwelling on is perhaps the obvious: to split the difference. In a 1932 essay titled “In Praise of Idleness,” the philosopher Bertrand Russell noted that he had come to think of work not as something morally necessary, but as a means to enhance pleasures in the rest of life (after all, would you want to attend a dinner party you could never leave?). While acknowledging that he is a product of a Protestant work ethic and thus a compulsive worker, Russell suggests halving the workday to four hours, which would be enough for a person to secure “the necessities and elementary comforts of life,” leaving the rest of his time to do whatever he wanted.

“There will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia,” Russell goes on. “The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion.”

“Beach, eat, drink, dance, repeat.” These are Rihanna’s favorite things to do in Barbados. In a June 7 interview with Conde Nast Traveller, the pop star gushed over her home country, a small island nation in the middle of the Caribbean. “When I’m in Barbados, all is right with the world,” she said. But not all was right with Barbados.

The same day, the local The Daily Nation newspaper reported on an “invasion of the Sargassum seaweed”—a brown, leafy algae that had washed up in thick mats on the white-sand beaches of the island’s eastern shores. The next day, the country’s government declared it a national emergency. Seen from afar, the bloom looked like a coppery oil spill slicking the sea. But a closer look revealed dead wildlife entangled within it.

The June Sargassum invasion in Barbados claimed the lives of three sea turtles, six dolphins, and “countless” fish and eels, The Daily Nation reported. But surely more have perished in the months since, as sheets of the bulbous-tipped seaweed—sometimes several feet deep—have become regular visitors to the country’s eastern and southern shorelines.

A dead baby sea turtle in beached Sargassum seaweed in Palm Beach, Florida.Nancy Jones Peterson

A dead baby sea turtle in beached Sargassum seaweed in Palm Beach, Florida.Nancy Jones Peterson“We’ve had mass mortality of sea turtles that have gotten trapped under ever-thickening piles,” said Hazel Oxenford, a Barbados-based fisheries biologist at the University of the West Indies. “When the turtles try to come up for air, they drown.” Because these Sargassum beachings are primarily happening during nesting season, which runs from March until the end of October, baby turtles attempting to crawl from their eggs toward the ocean are also getting caught in it.

Barbados isn’t alone. In the last six months, more than 700 beaches across the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico have been hit with mass beachings. Mexico, Belize, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and the British Virgin Islands are covered in it, taking a toll on tourism and fishermen alike. “The fishermen could not go to sea for two or three days,” a worker in Dominica told Hakai Magazine. “They couldn’t get the boats out because it was so thick.” South Florida, too, has seen an “assault.” It’s the worst year for Sargassum beachings ever.

There’s not a lot of history to trace, though. Sargassum algae only started becoming a real problem seven years ago. The true origin of these mass invasions, and the cumulative impacts of them, are thus not fully known. Some experts speculate there could be positive impacts along with the negative ones. But much of the story of this new phenomenon remains a mystery.

Sargassum researchers do appear confident in two things, though. The first is that these algal blooms constitute a new type of natural disaster—one that, like hurricanes, can be expected every single year. The second is that this new risk is not entirely natural. Humans have made these blooms far more likely.

There are more than 100 different species of Sargassum in the world, but two types in particular keep popping up on Caribbean beaches: Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans. Unlike most other types of seaweed, which begin life attached to the ocean floor, these species reproduce vegetatively on the ocean’s surface. They’re also thought to originate in the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic, the only named sea that never touches land; it’s bound only by ocean currents, leaving the sea itself relatively still.

The Riviera Maya in Mexico is suffering a seadweed onslaught this year, which the government is trying to stop with a barrier in the sea.STR/AFP/Getty Images

The Riviera Maya in Mexico is suffering a seadweed onslaught this year, which the government is trying to stop with a barrier in the sea.STR/AFP/Getty ImagesThe floating mats of Sargassum within the Sargasso Sea are so vast and thick, they often look like land masses. Out there, that’s always been a great thing. As the National Ocean Service explains, Sargassum mats provide “essential habitat for shrimp, crab, fish, and other marine species that have adapted specifically to this floating algae.” Threatened and endangered eels, sharks, and dolphinfish spawn there; birds use it for food. Commercial fish like tuna also feed on the algae, making the Sargasso Sea a fisherman’s dream.

Problems with Sargassum only started to arise in 2011. Seemingly out of nowhere, the seaweed began to amass in huge quantities on “beaches across the Caribbean, trapping sea turtles and filling the air with the stench of rotting egg,” according to a report in the journal Science. The foul odor stems from hydrogen sulfide, which the seaweed releases when it rots on land.

The 2011 event was originally considered a freak occurrence. “We thought it was all over,” Oxenford said. “But it came back in 2014, and then again in 2015 in a big way, and it spread much further.” This year, the Sargassum onslaught has stretched out over more than 1,000 square miles of the Caribbean Sea alone. And it’s not the only sea affected this year, according to a map of 2018 beachings.

Where did it all come from? Naturally, scientists originally assumed the Sargasso Sea. But in 2016, a team of researchers published a paper asserting it came from a huge patch of Sargassum floating in the tropical Atlantic, east of Brazil. “None of it ever tracked northward into the Sargasso Sea,” University of Southern Mississippi marine biologist James Franks, who worked on the paper, told Science. He believes ocean currents are sweeping this new source of Sargassum up the Brazilian coast toward the Caribbean.

Brian LaPointe, an algal bloom expert at Florida Atlantic University, said he also believes the tropical region near Brazil is the nursery from where it all came.* His research asserts the seaweed has a “dynamic existence,” continually moving from the equatorial currents toward the Caribbean and the Gulf Stream, with some eventually settling in the Sargasso Sea.

LaPointe considers all the Sargassum beaching events to be part of one big algal bloom: “The largest harmful algal bloom on our planet,” he said. And if he knows one thing about algal blooms, it’s that they thrive off of two things humans keep putting into the ocean: heat and nitrogen.

More studies will be required to fully understand Sargassum’s rapid spread, but a growing number of researchers feel comfortable pointing to humans as a culprit.

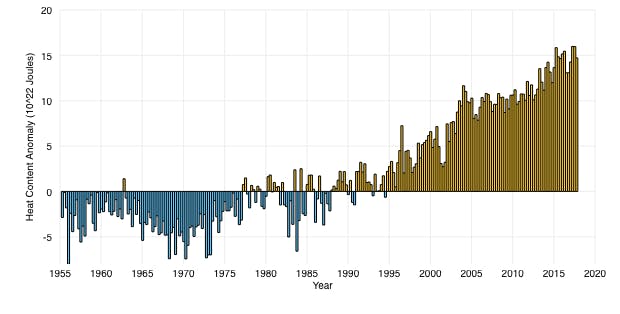

“This is another symptom of climate change and ocean pollution,” Oxenford said, pointing to how humans have warmed the ocean. As InsideClimate explains, “More than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gas emissions has been absorbed into the oceans that cover two-thirds of the planet’s surface.” In particular, the heat content of the ocean surface—where Sargassum grows—has increased dramatically since the 1950s. A 2017 study published in Biogeosciences cites “high anomalously unprecedented positive sea surface temperature” as a potential factor in the blooms.

Annual deviations from the long-term heat average in the top 700 meters of the ocean.climate.gov

Annual deviations from the long-term heat average in the top 700 meters of the ocean.climate.govLew Gramer, a marine scientist at the University of Miami, has also described a possible “correlation” between climate change and Sargassum’s spread due to changes in ocean circulation. “An unusual pattern of winds and ocean-surface circulation over the Sargasso Sea in late 2009 and early 2010 preceded the first mass beachings,” he said. “And this pattern actually coincided with an anomaly in a sea-level air pressure index that is also studied by climate scientists, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO).” Some researchers have linked changes in the NAO to global warming.

Another factor appears to be nitrogen, which humans have continuously poured into the ocean via fertilizer runoff and overflowing sewage systems. Nitrogen pollution is widely known to feed algal blooms, including Sargassum, and is a possible cause of the red tide plaguing the Gulf coast of Florida.

The main source of this pollution is still in dispute. The 2017 Biogeosciences study, for example, asserts the pollution responsible came from agricultural runoff into the Amazon River, as well as “deforestation, agroindustrial and urban activities in the Amazonian forest.”

Sargassum on the beach of the city of Le Gosier on the French Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe in April 2018.Helene Valenzuela/AFP/Getty Images

Sargassum on the beach of the city of Le Gosier on the French Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe in April 2018.Helene Valenzuela/AFP/Getty ImagesLaPointe, however, believes the Sargassum infestations are fed by all land-based nutrient pollution—from the Amazon, but also the Congo and the Mississippi, among other places. “We have greatly altered the nitrogen cycle on this planet,” he said, adding that local sources of nutrient pollution near Sargassum beachings are exacerbating the issue. In places like Florida and the Caribbean, those sources are most often inadequate wastewater infrastructure. “Human sewage is creating a much bigger role than anyone wants to admit,” he said.

If one thing is clear, though, it’s that the people who helped cause Sargassum’s spread are not all affected by Sargassum beachings. For Oxenford, that’s a frustrating reality. “It’s yet another man-made problem that’s been thrown at the Caribbean that isn’t our doing,” she said. But if the Caribbean and other affected areas are to thrive, they must figure out how to fix it—or at least prevent it from causing more damage.

Nancy Jones Peterson has seen the impact of Sargassum beachings up close. Earlier this summer, as she walked the beach at Phipps Ocean Park in Palm Beach, Florida, she came across a small but thick mat of brown algae. The registered nurse took a closer look, and found three dead baby sea turtles.

“There they are,” she said in a video posted to Facebook, her voice shaking. “The poor babies tried to get out to the ocean, and all these seaweed—caught up in the seaweed and they didn’t make it out.”

The Barbados Sea Turtle Project has been documenting similar discoveries on its Facebook page. In one video, a woman digs out an adult turtle from a pile of Sargassum even taller than she is.

This phenomenon has Oxenford particularly worried about the health of local marine environments. “As the seaweed stats to rot, the bacterial population grows enormously and you have huge oxygen demands,” she said. “It starts suffocating organisms.” The thickness of the seaweed mats also block sunlight from getting to sea grass and corals, threatening those organisms, too.

But Oxenford is adamant that not all is lost for local marine life or the tourism and fishing industries. Far from it. “We still have our sunshine and our clear water and beaches with no sargassum,” she said.

Due to ocean currents, Sargassum beachings are also only really happening on eastern and southern parts of Caribbean islands; the western and northern shores are clear. Sea turtle populations overall should be able to survive the beachings, as many nesting sites are not on affected beaches. Some tourist towns in Mexico have installed floating barriers to keep the seaweed from washing ashore. The U.S. has sent two Sargassum boats to help with cleanup in Quintana Roo region of Mexico, which includes Cancun and Playa del Carmen.

“I see this as a solvable problem,” Oxenford said. But not solvable in the sense that the Sargassum will ever go away. “It’s the same way hurricanes are not solvable,” she said. “But we’ll learn to live with it.” Living with it will require a new system where algal blooms are treated like hurricanes. Blooms will be predicted and forecasted, with different levels of alerts to denote the scale of the Sargassum event. Countries will need to implement management and response plans—and fund them appropriately. Ideally, Caribbean countries won’t have to pay for all of it, since they’re aren’t solely or even largely to blame for it.

It’s a daunting task, for sure, but Oxenford isn’t alone in looking at the silver lining. On a different walk on the beach a few days later, Peterson found another sheet of Sargassum—this one containing whole nest of dead hatchlings. “Around 50 to 100, they were all in the seaweed,” she said.

But this time, one was moving. There was no time to waste. Immediately, she said, she took it to the Loggerhead Marine Life Center in Juno Beach, where it she was told it would be rehabilitated and released. Her video from that day has a happy ending.

*Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly described Brian LaPointe’s research on the origin of massive Sargassum blooms. He does not believe they originated in the Sargasso Sea.

The CJ79 sports a 34" display, 21:9 aspect ratio, and 3,440 x 1,440 resolution. But its real draw is the inclusion of two Thunderbolt 3 ports.

The CJ79 sports a 34" display, 21:9 aspect ratio, and 3,440 x 1,440 resolution. But its real draw is the inclusion of two Thunderbolt 3 ports. The Predator Triton 900, unveiled by Acer during its IFA press conference in Berlin, is highlighted by an adjustable screen you can convert into different viewing modes.

The Predator Triton 900, unveiled by Acer during its IFA press conference in Berlin, is highlighted by an adjustable screen you can convert into different viewing modes. Intel announced six new processors in the new Whiskey Lake U-series and Amber Lake Y-series. Both are considered part of the 8th Gen Core lineup.

Intel announced six new processors in the new Whiskey Lake U-series and Amber Lake Y-series. Both are considered part of the 8th Gen Core lineup. News surfaced this week that Microsoft was planning on bringing a VR headset to the Xbox console but scrapped its plans earlier this year.

News surfaced this week that Microsoft was planning on bringing a VR headset to the Xbox console but scrapped its plans earlier this year.

No comments :

Post a Comment