Sexual abuse by Catholic priests and its cover up by bishops was always going to dominate this past weekend’s trip by Pope Francis to Ireland, but the explosive culmination of the trip with calls for his resignation was a surprise. Late Saturday night, an 11-page letter attributed to former Vactican diplomat Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò was published by a number of conservative Catholic sites in the United States and Italy. In it, Viganò alleged that Francis not only knew about charges of sexual misconduct committed by former Washington Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, but that Francis actually helped to rehabilitate the cardinal after Pope Benedict XVI removed him from public life.

The pope’s critics immediately called for his resignation. His supporters remain skeptical, suspecting that the forces that have plagued Francis since the start of his papacy are again trying to undermine his reform. Sorting through the allegations is difficult: As of yet, there is no clear corroborating evidence.

Viganò, who served as the Holy See’s representative to the United States from 2011 until 2016, alleges that the Vatican learned as early as 2000 of rumors of sexual misconduct involving McCarrick and young seminarians. McCarrick is alleged to have sexually harassed and assaulted seminarians during his time as a bishop in New Jersey in the 1980s and ‘90s by inviting seminarians to a beach house he owned, forcing them to share his bed, and pressuring them into sexual situations.

But Viganò uses vague language and euphemisms to describe what McCarrick did, so it is unclear if he told the Vatican or Pope Francis that he believed the former cardinal was guilty of abuse.

The Vatican, and specifically the retired pope’s staff, ignored warnings about McCarrick’s predatory behavior numerous times during the papacy of Benedict XVI, Viganò says: Memos he says he sent in 2006 and 2008 were not answered. Eventually, the former diplomat alleges, his warnings were taken seriously and Pope Benedict XVI imposed sanctions on McCarrick, in either 2009 or 2010, which he says forced McCarrick to move from a seminary where he was living in Washington and end his public ministry. Viganò also claims that McCarrick’s successor in Washington, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, was informed of the sanctions, though Wuerl denies being given information about them.

Shortly after Pope Francis was elected in 2013, Viganò says, the new pontiff lifted the alleged sanctions, eager to rehabilitate a cardinal whose more liberal stance aligned with the new pope’s.

Absent from Viganò’s letter is the allegation that eventually prompted Pope Francis to remove McCarrick from ministry: In June, the Archdiocese of New York announced that an allegation that McCarrick had sexually abused a minor more than 45 years ago had been substantiated. In July, McCarrick resigned from the College of Cardinals.

Viganò does not say in the letter that he explicitly told Francis that McCarrick sexually assaulted seminarians; the letter says Francis asked Viganò his thoughts on McCarrick, and that Viganò told the pope that McCarrick “corrupted generations of seminarians and priests.” The pope, Viganò says, did not reply.

The letter goes on to say that anyone who had knowledge of McCarrick’s sexual misconduct and who did not act—a group he says includes Pope Francis and Wuerl—should resign.

The letter cannot be dismissed easily. After all, this is a former high-ranking church official calling on the pope to resign. During his time in Washington, Viganò would have had access to the inner workings of the U.S. church, and he is making very specific allegations that can be corroborated or, in some instances, found to be untrue.

Pope Francis’s record on sex abuse has previously been called into question, making Viganò’s accusations at least plausible. Francis was slow to acknowledge sexual abuse by clergy in Chile; he has been defensive about the church’s current practices in combating sexual abuse; and just this weekend, he described a prominent victim-advocate, who has been supportive of the pope’s efforts at reform, as being “fixated” on the need for the church to hold bishops accountable.

But there are also good reasons to treat Viganò’s claims with skepticism. For one, a central claim of the letter—that Pope Benedict removed McCarrick from public ministry—is being questioned. In 2011, a year or two after Benedict allegedly imposed sanctions, McCarrick preached at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, ordained priests in New York, testified before the U.S. Congress and appeared on Meet the Press. The next year, McCarrick visited the Vatican with other U.S. bishops, where he attended a birthday party for Pope Benedict. Viganò stood near McCarrick at an awards dinner in New York in May 2012 and in 2013, McCarrick was seen shaking the hands of Benedict before the pope abdicated. McCarrick later celebrated Mass in Washington alongside Viganò.

Then there are questions about Viganò’s motives. The former nuncio opposes the Francis papacy’s reforms, and he has joined a group that routinely challenges the pope’s welcoming of divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to Communion and his (relatively) more progressive views on homosexuality.

Most of the men Viganò names in his letter also happen to be his ideological opponents.In fact, much of Viganò’s letter is devoted to condemning homosexuality. For example, he claims a “homosexual current in favor of subverting Catholic doctrine on homosexuality” is to blame in the church’s current crisis.

Most of the men Viganò names in his letter also happen to be his ideological opponents. Not least among them is Pope Francis himself, who in 2016 recalled Viganò to Rome, in part because he was unhappy with the nuncio’s role in arranging a 2015 meeting in Washington between Francis and Kim Davis, the former Kentucky clerk who refused to sign a marriage certificate for a same-sex couple.

Viganò also claims that McCarrick was instrumental in the selection of three influential U.S. bishops who are seen as allies of Francis, a charge that could undermine their ministries. Each of them—Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark and Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego—released statements dismissing the letter and calling out factual inaccuracies.

When it comes to sexual abuse, Viganò’s own record is checkered, which may undermine his claims that his conscience demanded he make these allegations against McCarrick public. In 2014, Viganò is reported to have prematurely ended an investigation into allegations that Archbishop John Nienstedt, a conservative and an outspoken critic of same-sex marriage, mishandled sex abuse allegations. During that investigation, allegations of sexual misconduct by Nienstedt himself surfaced, and there are claims that Viganò ordered that an incriminating letter be destroyed. Nonetheless, Nienstedt stepped down from his post in 2015.

The timing of the letter’s release also raised eyebrows, as it hit the Internet just hours before Pope Francis would fly from Ireland back to Rome. This meant Pope Francis would face the press during his customary in-flight press conference and that the letter’s charges would dominate the news cycle, rather than the trip itself—a striking parallel to the pope’s 2015 visit to the U.S., where news of the pope’s meeting with Davis was released just as the trip wrapped up.

When asked about the allegations during Sunday’s press conference, Francis said he would not comment. He urged journalists to look into the claims and to come to their own conclusions. But he did not rule out commenting in the future.

The allegations raised by the archbishop come at a time when confidence in Francis’ papacy appears shaky. Sexual abuse in the church is once again dominating the headlines, and the Vatican seems unable to quell criticism that it understands the gravity of the situation. But when it comes to victims themselves, some are accusing Viganò of co-opting their trauma to advance his own agenda.

As Juan Carlos Cruz, a survivor of sexual abuse by a priest in Chile, put it in a tweet on Monday, Pope Francis has work to do when it comes to holding priests and bishops accountable.

But, he asks, “where was Viganò when it came to do something for victims? He is just a fanatic who blames gays and represents ultra conservatives who want power and use survivors as their way to get it.”

The Kansas City Federal Reserve, one of the dozen reserve banks in the U.S., gathered on Friday in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to discuss a signature puzzle of our times: How can the economy hum along, with unemployment falling for years, without wage growth? How have the gains from the economy been segregated from most Americans who do the work, instead flowing into the hands of a small group at the top? And what can the Fed, or anyone, do to reverse this?

The main culprit discussed at the economic policy symposium was increasing corporate concentration: the limited number of firms in any one industry. A series of working papers and speeches examined monopolization’s impact on various aspects of the economy, from worker bargaining power to capital investment to inflation. While the Fed isn’t singularly responsible for policing market competition, it does have the power of the megaphone, and the implications of the research unveiled last week should signal a sea change across government: either tame the corporate giants, or watch helplessly as they eat everything not nailed down.

Northwestern University’s Nicolas Crouzet and Janice Eberly submitted a paper about what they call “intangible capital”—intellectual rather than physical property, such as patents, software, or even copyrighted brands. Over the last two decades, businesses have invested more in these intangibles than in physical capital like factories and workers; according to the authors, this can account for nearly all of the drop in physical capital investment since 2000. If you have a patented product that nobody else can manufacture, why bother to spend money attracting top talent?

Crouzet and Eberly show this dynamic is most pronounced in the tech and health care sectors, where patents are particularly valuable. “The platform developed by an online retailer is just as crucial to producing revenue as an oil platform is to an energy firm,” the authors write. And they see a link to market power, as large firms use intangibles to exclude competitors.

This is important to the Fed because in economic downturns, it lowers interest rates to entice capital expenditures and give the economy a boost. Similarly, Congress often tries to kick-start the economy with investment tax credits. If apps and drug patents are more critical to the modern economy, these interventions won’t work as well.

An even more intriguing paper, from Alberto Cavallo of the Harvard Business School, scrutinizes the rise of online retail and the algorithms that cause prices to constantly fluctuate. If Amazon finds that more people buy pens in the morning, pens could be more expensive then, for example. And because the retail world has a “follow-the-leader” mentality when it comes to Amazon, this has been widely replicated, leading to a high degree of uniformity across the country.

In other words, Amazon has created its own ecosystem, with precise, rapid swings in prices not necessarily related to the common factors of supply and demand. You might expect that Amazon’s presence lowers prices generally, as it tries to undercut the competition. But by studying thousands of prices, Cavallo finds that the “Amazon effect” can react faster to “shocks” like spiking gas prices, natural disasters, a sudden change in the value of the dollar, or tariffs. When these shocks happen, companies can transfer the price to customers faster than ever. “The implication is that retail prices are becoming less insulated from these common nationwide shocks,” Cavallo writes.

With consumer spending encompassing most of the U.S. economy, this dynamic pricing has made the country more vulnerable to surprise events. It’s expressly tied to concentration, Cavallo notes: “A few large retailers using algorithms could change the pricing behaviour of the industry as a whole.” Part of the Fed’s job is managing inflation, but this paper implies that it’s out of their hands and more at the whim of an algorithm somewhere in Seattle.

Alan Krueger of Princeton University didn’t write a paper, but his remarks at Jackson Hole reflected growing research into “monopsony.” Monopoly means too few sellers in a market; monopsony means too few buyers, and in this context, too few employers. If there aren’t as many bidders for a worker’s services, their ability to bargain for a higher wage is reduced. To Krueger, this can help explain the lack of wage growth, despite low unemployment. “If employers collude to hold wages to a fixed, below-market rate, or if monopsony power increases over time, then wages could remain stubbornly resistant to upward pressure from increased labor demand in a booming economy,” Krueger said.

All of these events—the rise of intellectual property, dynamic pricing, and weakened labor bargaining power—have links to monopoly. These researchers are saying, collectively, that the economy has fundamentally changed as a result. The normal tools used to manage economic growth, like shifting interest rates or containing inflation, used to be enough to ensure that the market would bring higher wages and broadly shared prosperity. But those channels have been broken, and may stay broken until dominant firms are cut down in size and power.

This lack of control over the economy is incredibly dangerous. The Fed has tools to regulate and even break up the banking sector, though they are not using them. But the agencies that oversee business competition—the Justice Department’s antitrust division and the Federal Trade Commission—have the primary authority to guard against harmful market concentration. If the conclusions from Jackson Hole are correct, economic policymakers desperately need their help.

The American Civil Liberties Union last week joined a closely watched court case, taking sides with a national advocacy organization against a powerful New Yorker who’s accused of enacting a retaliatory and unconstitutional policy. For once, this person wasn’t President Donald Trump.

The ACLU’s latest opponent is Andrew Cuomo. In May, the National Rifle Association sued the New York governor on First Amendment grounds, alleging that he’s trying to force the gun-rights organization into financial ruin by pressuring banks and insurance companies into severing their business ties with it.

Cuomo is far from the only Democratic politician who is openly hostile to the NRA. But the NRA believes the governor went too far by using New York’s regulatory agencies to intimidate the state’s financial sector into blacklisting the organization. The NRA says the move has caused “tens of millions of dollars in damages” and could leave it “unable to exist” or to “pursue its advocacy mission,” as Rolling Stone first reported earlier this month.

The governor responded with a sarcastic tweet that the organization would be in his “thoughts and prayers,” and has asked the federal court considering the lawsuit to dismiss it. Last Friday, the ACLU filed a brief urging the court to reject Cuomo’s request. Cuomo thus has achieved something of a miracle in the Trump era: uniting the organization most vociferously opposing the president with the one that helped elect him.

“There are acceptable measures that the state can take to curb gun violence,” David Cole, the ACLU’s legal director, wrote last week. “But using its extensive financial regulatory authority to penalize advocacy groups because they ‘promote’ guns isn’t one of them.” Multiple conservative media outlets took note of the ACLU’s intervention in the case, often with an air of surprise at the unlikely alliance. Most of the mainstream outlets that covered the lawsuit earlier this month ignored or did not notice the latest development.

That omission is unfortunate. Cuomo is widely believed to be interested in running for president in 2020. He and his fellow hopefuls will likely be running as the antidote to Trumpism. But Cuomo’s campaign against the NRA suggests that he could wield power in a manner that’s eerily similar to the current president.

The legal battle began in the fall of 2017, when New York’s Department of Financial Services launched an investigation into Carry Guard, a NRA-sponsored insurance policy that covers legal costs if a policyholder faces any civil or criminal liability in using a lawfully owned gun. The DFS announced its inquiry amid pressure from Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun-control organization that opposes the NRA, to investigate the program. Everytown argued that the policies violated New York laws that bar insurance companies from providing coverage that would cover criminal-defense costs, a conclusion with which DFS eventually agreed.

Cuomo had already carved out a reputation for hardline rhetoric toward the National Rifle Association. In 2014, he said that conservatives who defend civilian assault weapons “have no place in the state of New York.” The following year, he accused the NRA of defending the Second Amendment rights of people on the government’s no-fly list. Sometimes he matched his words with actions: After the Sandy Hook massacre in 2013, New York passed the NY SAFE Act, which Cuomo has touted as among the nation’s strictest gun-control laws.

There’s nothing wrong with DFS regulating insurance policies in its jurisdiction. Nor is there anything inherently amiss about Cuomo’s public criticism of the NRA, and vice versa. Things didn’t really begin to go awry, according to the NRA, until the spring of 2018. In the lawsuit, the organization claims that insurance providers began to cut ties with them under covert pressure from state regulators. Lockton Companies, the Carry Guard provider that worked with the NRA for two decades, told the organization it would have to end the relationship or risk losing their New York licenses.

Days later, the NRA says, a major New York insurance company dropped out of negotiations to serve as the organization’s corporate carrier after learning about Lockton’s decision and the alleged threats against it. The NRA’s lawsuit claims that it has subsequently struggled to find a provider for insurance policies it needs to function, such as general-liability insurance to cover its day-to-day operations as well as media-liability insurance for NRA TV, the organization’s streaming service.

The alleged campaign against the NRA came at a pointed moment for the organization. Two weeks before Lockton’s decision, a teenage gunman shot and killed 17 students and teachers at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The massacre revived America’s intermittent debate about the Second Amendment and re-energized gun-control activists, who led a wave of boycotts against the NRA’s corporate partners. Cuomo leaped into the fray by urging lawmakers in other states to resist the organization’s political power and adopt more stringent measures like the SAFE Act.

In April, Cuomo took more aggressive steps. He formally directed DFS Superintendent Maria Vullo, a former aide for the governor, to urge New York companies to “weigh [the] reputational risk” of their business relationship with the NRA. “The Department encourages regulated institutions to review any relationships they have with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations, and to take prompt actions to managing these risks and promote public health and safety,” Vullo wrote in her formal guidance to state businesses.

The statements don’t actually direct any businesses to cut off ties with the NRA. At most, they are phrased as sternly worded advisory notices. But such words from a state financial regulator are hard to ignore, especially when the governor is backing them up explicitly. “The NRA is an extremist organization,” Cuomo wrote on Twitter the following day. “I urge companies in New York State to revisit any ties they have to the NRA and consider their reputations, and responsibility to the public.”

It’s a nice business you’ve got there, the governor seemed to be saying to Wall Street. It’d be a shame if something were to happen to it. In May, a few weeks after DFS sent the notices, state regulators announced consent orders against Lockton Companies and Chubb Group Holdings related to the Carry Guard program; both companies were barred from working with the organization in the future. According to the NRA, the one-two punch of the advisory notice and the consent orders sent a chilling effect throughout its business relationships.

“The NRA has spoken to numerous carriers in an effort to obtain replacement corporate insurance coverage; nearly every carrier has indicated that it fear transacting with the NRA specifically in light of DFS’s actions against Lockton and Chubb,” the NRA said in its lawsuit. The organization also alleged that New York’s tactics had “imperiled the NRA’s access to basic banking services,” and claimed that multiple banks withdrew from negotiations because they feared that “any involvement with the NRA ... would expose them to regulatory reprisals.”

This may sound like great news to the NRA’s opponents. But Cuomo’s tactics would anger liberals if used against organizations with which they align. It’s not impossible to imagine a hardline Republican governor taking similar steps with state financial regulators to blacklist legal-aid groups that represent undocumented immigrants, or nonprofit organizations that advocate for reproductive rights, or even the ACLU itself. “Substitute Planned Parenthood or the Communist Party for the NRA, and the point is clear,” the ACLU wrote last week. “If Cuomo can do this to the NRA, then conservative governors could have their financial regulators threaten banks and financial institutions that do business with any other group whose political views the governor opposes.”

To that end, the organization urged the court to allow the NRA’s lawsuit to proceed to the fact-finding and discovery stages. “If the NRA’s allegations were deemed insufficient to survive the motion to dismiss, it would set a dangerous precedent for advocacy groups across the political spectrum,” the group warned. “Public officials would have a readymade playbook for abusing their regulatory power to harm disfavored advocacy groups without triggering judicial scrutiny. And it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, for any advocacy group to operate effectively without routine access to basic banking and insurance services.”

Cuomo himself is not being subtle about his goals. In interviews with news outlets earlier this month, he described the NRA’s lawsuit as frivolous and downplayed the scope of DFS’s actions. (The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment for this article.) Elsewhere, he’s even more boastful about his efforts. “New York is forcing the NRA into financial crisis,” he wrote on his official Facebook account earlier this month. “It’s time to put the gun lobby out of business. #BankruptTheNRA.” In an earlier post, he declared, “We’re forcing the NRA into financial jeopardy. We won’t stop until we shut them down.”

The remarks almost seem designed to prove his critics right. Indeed, the NRA cited those posts and others like them to help demonstrate Cuomo’s intent to violate the organization’s First Amendment rights. This may sound familiar. Last year, Trump made legally self-injurious comments on Twitter and elsewhere about his ban on travel from several Muslim-majority nations, and some were cited by lower courts when ruling against its constitutionality. There’s a vast moral difference between these cases, but both share a common thread: using the state’s tremendous powers to inflict deliberate harm on a disfavored group. It’s doubtful that Democrats can truly defeat Trumpism by adopting it for themselves.

Elon Musk’s dream is dead. Less than three weeks after tweeting that he was taking Tesla private, and that he had secured funding to do so, Musk published a statement announcing that the electric car company would stay public after all.

It is, however, hard to back down from something that was never going to happen in the first place. Musk never had any funding for his plan, as his letter made clear. He had not discussed going private with Tesla’s board or informed the company’s investors. His own idea of “going private” appeared to be a strange fantasy—a hybrid of public and private that ultimately added up to Musk never having to take earnings calls, while retaining all the benefits of staying public, like maintaining access to capital markets and a diversified shareholder base.

Fantasy or not, Musk has found himself in hot water because of his now notorious tweet. The Securities and Exchange Commission is reportedly investigating him for possible securities fraud. Many investors are angry and could sue the company. The statement on Friday was an attempt to minimize the potential consequences of Musk’s rash actions. His decision to keep Tesla public may quell the controversy he’s brought on himself, but his statement—and reports circulating about his behind-the-scenes decision-making—point to more trouble ahead.

If there’s one message in Musk’s letter it’s this: He is listening. He is listening to Silver Lake, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley, the financial advisers that made it clear how difficult it would be to take the company private. He’s listening to shareholders, who would have lost their stakes in the company in a privatization drive. He’s listening to the board of directors, who were in the dark about Musk’s plans.

Musk being Musk, however, he didn’t apologize or acknowledge that he might have erred. He even suggested that he did have the phantom funding to take Tesla private. “My belief,” he wrote, “that there is more than enough funding to take Tesla private was reinforced during this process.” Translation: “I could have done it, if I really wanted to.”

The letter was similar to an earnings call that Musk conducted earlier that month. He received plaudits for clearing the low bar of not repeating the erratic behavior he displayed on a previous earnings call. In contrast to his tweets, the letter showed a certain level of maturity (you can practically see the fingerprints of lawyers, Tesla’s board, and PR consultants). It communicated what many people want to believe, that Musk is a responsible guy who knows what he’s doing.

But the reporting very much suggests the opposite. From Bloomberg, we learn that the Saudis, whom Musk claimed were going to back his privatization plan, were not happy that Musk was running his mouth about their involvement. From The New York Times, we learn that Musk did not see the obvious problem of an electric car company whose stated ambition is to save the world from climate catastrophe taking tens of billions of dollars from the world’s richest petro-state. From The Wall Street Journal, we learn that Musk did not seem to understand that taking the company private would necessitate losing the company’s fiercely loyal investors—or that it would likely mean collaborating with a large automobile manufacturer, like Volkswagen. Nor, the Journal reports, did Musk seem to realize that the new money would come with “strings attached” that might be more onerous than the dog-and-pony show he has to perform every quarter.

It has been clear for some time that Musk is impulsive, combative, and increasingly erratic. But the last three weeks have shown that he also doesn’t know what he’s doing.

Musk’s ignorance of the mechanics of taking a large company like Tesla private is not disqualifying in and of itself. There are surely a number of CEOs who don’t know the first thing about such matters. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, for instance, has never suggested he knows the finer points of securities law. One of the good things about being a CEO is that you can consult experts and lawyers and they will take care of it.

What Musk’s strange odyssey reveals, however, is a lethal combination: a depth of ignorance that is exacerbated by an unwillingness to learn what he doesn’t know. The next few months are pivotal for Tesla, which has struggled to meet production goals and has burned through billions of dollars trying to become a sustainable producer of sustainable automobiles. Musk’s recent behavior suggests that he’s outmatched by the responsibility and challenge of running a company like Tesla.

Tesla is stuck in a paradox. On the one hand, Musk’s involvement is key. Investors believe he is a generational talent, the next Steve Jobs. Even as Tesla has struggled, investors are often soothed by his mere presence. On the other hand, Musk’s bizarre behavior has imperiled the company. Tesla can’t succeed without him—but can it succeed with him?

When Joan Didion came out to the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 60s, she saw decline and decadence, a center no longer holding. In her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” she chronicled the moral drift that had seized America, a country where “we had aborted ourselves and butchered the job,” a nation that had lost its way and its purpose.

PALE HORSE RIDER: WILLIAM COOPER, THE RISE OF CONSPIRACY, AND THE FALL OF TRUST IN AMERICA by Mark JacobsonBlue Rider Press, 384 pp., $27.00

PALE HORSE RIDER: WILLIAM COOPER, THE RISE OF CONSPIRACY, AND THE FALL OF TRUST IN AMERICA by Mark JacobsonBlue Rider Press, 384 pp., $27.00When Milton William Cooper, nine years her junior, came to the Bay Area a few years later in 1975, fresh from military service, little had improved. He, too, saw moral decline, depravity, and decay taking hold. But for Cooper, this did not present evidence of entropy. Things weren’t falling apart. On the contrary, everything was working according to a secret scheme, engineered by a shadowy cabal of figures gathered under names like The Bilderberg Group, the Trilateral Commission, and the Illuminati. The center was holding just fine; this was all part of its plan for the subjugation of humanity.

Cooper’s past allowed him to claim a kind of credibility for these theories. At the tail end of the Vietnam War, he had worked in Naval Intelligence, as part of the briefing team under Admiral Bernard A. Clarey. He would later claim that at one point while on the Admiral’s staff, he’d gotten a glimpse of a cache of top secret documents revealing a vast government conspiracy against America’s citizens. Among the files Cooper said he found in Clarey’s cabinet was evidence that JFK had been assassinated not by Lee Harvey Oswald, or a shadowy figure from the grassy knoll, but by his driver, using “a gas pressure device developed by aliens from the Trilateral Commission.” Admiral Clarey’s Cabinet became Cooper’s own Joanna Southcott’s Box, a repository of secrets known only to Cooper, whose contents seemed to change and evolve over the years, fitting whatever need Cooper’s current conspiracies had.

From the late 1980s until his death in 2001, Cooper became one of the best-known and most-influential conspiracy theorists, beloved by figures ranging from Timothy McVeigh (who visited Cooper shortly before the Oklahoma City Bombing) to Alex Jones (whom Cooper despised) to members of the Wu-Tang Clan. Through his radio broadcast, The Hour of the Time, he popularized the phrase “Wake up, sheeple” and injected a host of now-common conspiracy theories into the mainstream: not just his JFK theory, but also postulations that AIDS was one of many secret weapons devised by the US government for use against its own people.

Mark Jacobson’s Pale Horse Rider: William Cooper, the Rise of Conspiracy, and the Fall of Trust in America traces Cooper’s life and the unlikely spread of his book Behold a Pale Horse, released in 1991 by Melody O’Ryin Swanson, a New Age publisher who claims she’s never read it, despite its perennially strong sales. It’s a story of the incubation of the politics of conspiracy, a kind of prologue to our era of Birthers, Pizzagate, and QAnon. Framing his book around Donald Trump’s win on November 8, 2016 (when, Jacobson writes, the presence of Cooper’s ghost became “palpable”), Behold a Pale Horse attempts to connect this story to the world we now inhabit, one where belief has eclipsed truth, and paranoia has eclipsed trust.

Cooper first came to prominence in the late 1980s, through an early Internet message board devoted to UFOs called Paranet. John Lear, the disinherited son of the Learjet magnate, had been posting wild conspiracies about secret government relations with aliens. They were the kind of thing no one took very seriously, until Cooper appeared from nowhere, corroborating them. With his background in Naval Intelligence, his supposedly independent verification of Lear’s bizarre story gave it instant credibility (When Paranet’s mod Jim Speiser first introduced Cooper to the board, he described Paranet as being “deeply indebted to, and a little honored by” Cooper’s presence.)

Soon, Lear and Cooper had teamed up, relaying an increasingly manic and terrifying story of alien collusion with secret governmental forces while drinking each other under the table. In 1989 they released an “Indictment” against the US government, demanding it “cease aiding and abetting and concealing this Alien Nation which exists in our borders.” They went on to demand that it must “cease all operations, projects, treaties, and any other involvement with this Alien Nation,” and ordered “this Alien Nation and all of its members to leave the United States and this Earth immediately, now and for all time, by June 1, 1990,” calling finally for a full disclosure of all Alien-Government interactions.

Aliens were never more than a gateway drug for Cooper; they helped prime the pump for a conspiratorial paranoia towards the government.Their accusations were ludicrous, of course, but had an important and still largely underappreciated effect. As conspiracy theorist Michael Barkun has explained in his 2003 book A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America, the convergence of UFO beliefs and general conspiracy theories “brought conspiracism to a large new audience. UFO writers have long been suspicious of the U.S. government, which they believe has suppressed crucial evidence of an alien presence on earth, but in the early years they did not, by and large, embrace strong political positions.” Cooper and Lear helped change all that; they were the tip of a spear asserting that the number one thing we had to fear was not little green men, but the government that colluded with them, appropriating their technology against us. In the X-Files-esque decade that followed, Cooper’s ideas, Barkun notes, “brought right-wing conspiracism to people who otherwise would not have been aware of it.”

Cooper’s dalliance with the UFO community only lasted a few years. In part this was because he kept turning on his friends. Ever-paranoid, he and Lear had an acrimonious falling out, and soon Cooper was accusing Lear of being a CIA plant. But aliens were never more than a gateway drug for Cooper; they helped prime the pump for a conspiratorial paranoia towards the government, murmurings that the government was keeping important secrets from its citizens—and this was what really mattered. Cooper soon began arguing that he’d been purposefully misled by the government about aliens, that they’d fed him the story to trick him into ignoring the bigger conspiracy: the One World Government, which, run by the Illuminati, presided over everything.

UFOlogy appears in Cooper’s 1991 opus, Behold a Pale Horse, but then again, so does everything else. Behold A Pale Horse is a singular book not just because it acts as a clearing house for so many varieties of paranoia and conspiracy, but for its form. From its primal, cosmic cover to the variety of fonts and page layouts, it is less a book than a heap of zines and secret dispatches hurriedly patched together. With the tentacles of the conspiracy reaching everywhere, the book can’t hope to make sense of it all; instead its lens zooms in and out of focus, erratic and hyperactive, drawing lines and connecting threads. It is both compulsively readable and intolerably incoherent—a perfect transcription of a charismatic paranoid ranting at you on a street corner.

“For Cooper,” Jacobson notes, “truth and falsehood began with the document. Be it Dead Sea Scrolls, the Revelation of St. John, the Golden Plates of Joseph Smith, or a stack of papers found in a cabinet at Naval Intelligence, the secret document contained the seed to be worked into the ever-expanding concept, or what people came to call a meme.” Behold a Pale Horse, like so much of conspiracism, is a hermeneutics gone feral; it is a love letter to the text itself, the sacred and secret document. In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with William Cooper.

Behold a Pale Horse, like so much of conspiracism, is a hermeneutics gone feral; it is a love letter to the text itself, the sacred and secret document.The most troubling element of Behold a Pale Horse is that it contains, in its entirety, the debunked hoax The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Cooper insisted, bizarrely, that such a move was not anti-Semitic, that the Jews in the pamphlet were supposed to be read as “the Illuminati,” since it was they—not Jews, or Catholics, or African-Americans—who were the true villains. Nonetheless his book provided a way for a notoriously vile piece of libel to find its way back into an increasingly anti-Semitic fringe community (one that, increasingly, is no longer all that fringe). The preponderance of YouTube videos asserting that the Protocols are real and that Jews are the cause of all modern life’s ills, no doubt owes a great deal to Cooper’s book.

As with the Protocols, much of the rest of Behold a Pale Horse’s contents is not new. A chapter on FEMA Camps is, for instance just one of many that borrows from other conspiracists, regurgitated slightly or plagiarized wholesale; it reproduces the story that the government has set up various sites around the country (usually identified as prisons, disused train yards or warehouses, and former Walmarts) to be used at the dawn of the New World Order for the internment of patriots. The success of Cooper’s book lay not in its originality but in its encyclopedic synergy of American paranoia, threaded through a thousand different nodes of conspiracy, a bound and printed Crazy Wall kept behind the counter at your local Barnes & Noble.

The cult status of Cooper’s book was only bolstered by the manner of his death in 2001. By the late 1990s, Cooper had stopped paying taxes, fortressing himself atop a mesa in Arizona. Warrants were issued for his arrest, but the FBI wanted to do anything to avoid another Ruby Ridge, so they watched him for years, hoping to catch him off his property. Meanwhile, Cooper began to predict his own death: “They’re going to kill me, ladies and gentlemen,” he told his radio audience. “They’re going to come up here in the middle of the night, and shoot me dead, right on my doorstep.” Two months after 9/11 his prophecy came true: a botched attempt by the FBI to draw him out of his compound backfired, leading to a firefight between Cooper and almost a dozen federal agents, in which one FBI agent and Cooper were both killed.

Like a Cooper monologue, Pale Horse Rider veers off on a variety of tangents, some superfluous, some fascinating, some both at once. Among the most interesting tangents is the recurrent digression into Cooper’s prominence among Black communities, and the preponderance of his ideas in hip-hop. Cooper has been name-checked by everyone from Tupac to Public Enemy and Gangstarr, to say nothing of MC Pale Horse and Black Militia member Arthur Kissel, who performs under the name William Cooper. Indeed, Pale Horse Rider is as much a biography of a book—Behold a Pale Horse—as it is of its author. Behold a Pale Horse, in many ways, has lived a more fascinating life anyway, particularly in its ability to resonate with a disparate collection of communities and voices.

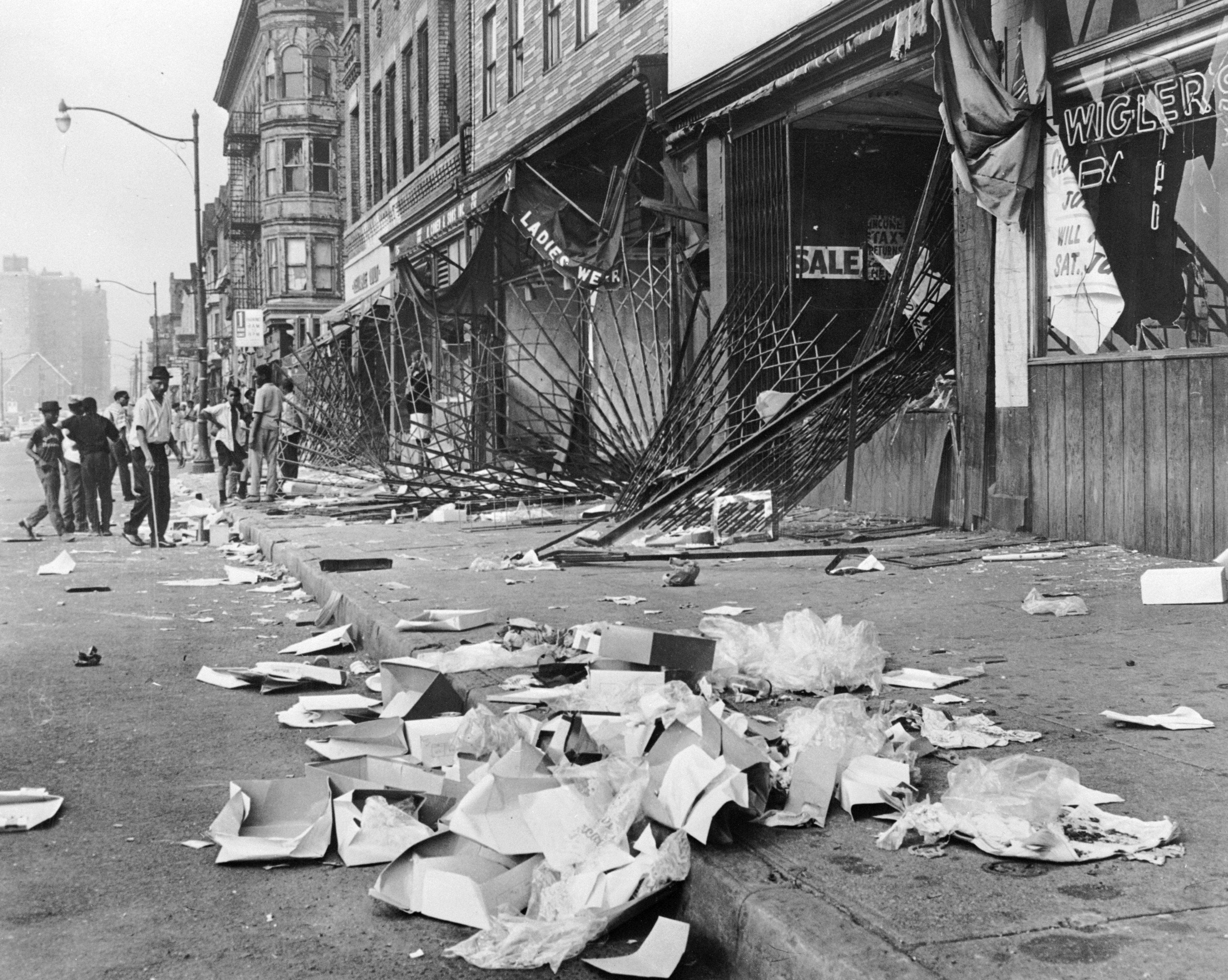

In Harlem, Cooper’s book became a regular feature of the sidewalk booksellers in the early 90s, alongside James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “Most people, anyone who once thought of themselves as radical in any way back in the 1990s, knows William Cooper,” one Harlem resident tells Jacobson. But it was in the U.S. prison system that the book truly flourished, copies passed from hand to hand until they disintegrated. “One in four black men winds up in jail one time or another,” a bookseller explains to Jacobson. “The incarcerated African American is the most legitimately paranoid man in the world. When you get to William Cooper, he is one paranoid white man, he speaks the same language.”

As Wu-Tang’s Ol’ Dirty Bastard put it, summing up much of Behold a Pale Horse’s allure: “Everybody gets fucked. William Cooper tells you who’s fucking you.” Except, of course, Cooper doesn’t tell you who’s fucking you; Cooper tells you an increasingly elaborate but ultimately reassuring story that you got fucked because of some omnipotent conspiracy, which takes the messiness out of life and the burden off yourself.

Cooper refused to see America’s hypocrisies as the result of a hundred grifts and petty cons, a chaotic mish-mash whose effects were essentially random.Take for example Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, the South Africa’s former health minister who, while still in office and at the height of that country’s AIDS crisis, distributed copies of the chapter that argued that AIDS was introduced into the African population by a global conspiracy with the goal of reducing the continent’s population. Like ODB and the booksellers of Harlem, Manto used Cooper’s writing to make a point about colonial racism—but what South Africa needed from its government was not conspiracies but retroviral medicine and comprehensive sex education. In the United States, systemic racism is real and omnipresent, but it works through voter suppression and local private prisons, jaywalking fines and asset forfeiture, housing covenants and employment discrimination and a million other diffused tactics. Black Americans and their allies need political organizing and activism, not fantasies involving Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars.

The fundamental flaw with Cooper’s logic—and one that is consistently being made on both the right and the left—is the confusion of corruption with conspiracy. Corruption, a constant in capitalism (and, for that matter, human nature generally) is opportunistic as often as it is planned, the work of lone grifters and complicated organizations. It often involves conspiracy (in the legal sense of the word), of course, but it is not the same as the conspiracy that Cooper envisioned. Cooper, in effect, saw all of American (and global) capitalism as part of the same tightly controlled, well-oiled machine working in perfect and absolute concert to achieve a set of predetermined ends. He refused to see America’s shortcomings and hypocrisies as the result of a hundred grifts and petty cons, a chaotic mish-mash whose effects were essentially random and almost always uncoordinated.

Frustratingly, Jacobson too often repeats Cooper’s theories without providing much context, allowing them to sit on the page unchallenged. Cooper’s theory of why “Income Taxes Are Voluntary,” or how the World Trade Center collapse began with a controlled explosion before the planes hit the towers, are not even given the most cursory of fact-checks. When Jacobson writes that “9/11 deserved Truth, or at least the semblance of an effort. Instead it got Osama bin Laden with his nineteen men with Exacto-knives, along with a president too engrossed with My Pet Goat to call in the SWAT teams,” it’s hard to know if he’s ventriloquizing Cooper or speaking for himself.

The biographical details are even more difficult to parse; Jacobson often makes little attempt to distinguish between life events that might have actually occurred versus those invented by a deeply paranoid fabulist, leaving the reader with no real means to judge the book’s contents. Pale Horse Rider, for example, credulously recounts the circumstances in which Cooper lost his right leg: According to his own accounts, Cooper tried to tell a journalist about what he’d seen in Admiral Clarey’s Cabinet, and shortly after that, while bicycling down a mountain road, a black car tried to run him off the road. Two men stood over him, discussing whether or not he was dead. A second accident a month later, supposedly by the same car, would cost him his leg; he would later add that he was visited one night in his bedroom by two men further warning that if he opened his mouth again about what he’d seen they would finish the job. “I told them that I would be a very good little boy and they needn’t worry about me anymore,” so they left him alone.

What, of any of this, has any basis in reality? It’s impossible to know for sure, since Jacobson makes little effort to bolster any of Cooper’s story with independent verification (or, when he does, he rarely makes that explicit to the reader). All of it strains credulity and makes reading the biography, at times, as vertiginous as listening to a Cooper broadcast.

One supposes that Jacobson is giving Cooper enough rope to hang himself, and letting the reader infer that these theories are ludicrous. But this rhetorical strategy has serious flaws. If the past few years have taught us anything, it’s that giving a white supremacist, for example, free rein to rant and rave is no guarantee that audiences will be repulsed. Similarly, recounting even Cooper’s most wild conspiracy theories with a straight face is by no means any guarantee that the reader will reject them. Indeed, Pale Horse Rider seems designed to be enjoyed both by the skeptic and the believer; die-hard fans of Cooper will not find any of their own core beliefs challenged here.

By the book’s end, Jacobson has seemed to embrace the relativism that allows conspiracies to flourish: The Cooper in his book, he confesses, “might not be the version of those who lionized the man, or who hated his guts, but it was where my own research took me, the particular truth I found. As a member of the audience, I was entitled to it.” Pale Horse Rider ends up offering a picture of the current moment, albeit not in the way Jacobson may intend. It is, in the end, less an explanation of a phenomenon than a symptom of it: Any charismatic voice in the wilderness, listened to ad nauseum, can start to sound lucid.

No comments :

Post a Comment