President Donald Trump’s proposal last month to weaken the Endangered Species Act has sparked a familiar debate. Environmentalists say he’s shilling for the fossil fuel and logging industries, which seek to exploit federally protected land. Those industries say environmentalists are overreacting—that loosening the law’s requirements will allow economic development alongside species protection.

But one group with a big stake in the Endangered Species Act’s future hasn’t caught much attention. Trophy hunters—those who hunt large, often endangered or threatened wild animals in order to keep and display their carcasses—are applauding the idea of a weakened Endangered Species Act, which may make it easier to import dead leopards, giraffes, and other exotic animals to the United States.

The law, which was passed in 1973, bans the import of trophies for endangered or threatened species. The Trump administration, however, is proposing to repeal automatic protection for the latter category. (Threatened species are at less risk of extinction than endangered species.) If that happened, any newly designated threatened species would not receive protection from trophy hunting unless the Trump administration created a special regulation.

Animals rights advocates say this is particularly worrisome for the giraffe. As the population of the world’s tallest mammal has plummeted, groups have petitioned for the giraffe to be protected under the Endangered Species Act. It’s likely that the giraffe will only be granted threatened status—meaning it won’t get trophy hunting protections. Giraffe trophies are highly sought after by Americans, with an average of around one animal imported per day, according to NPR.

If the proposed change to the Endangered Species Act goes through, it would be just the latest favor to the trophy hunting community. Under Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has reversed a host of bans on big-game imports, including elephant and lion carcasses from several African countries including Zimbabwe and Zambia. As such, Zinke has granted more than three dozen import permits for dead lions, some from previously banned countries, during his tenure. Zinke has also created an wildlife conservation council for the sole purpose of promoting trophy hunting, and stacked it with trophy hunters and gun advocates.

Taken together, animals rights activists say, these actions have created the most friendly policy environment for trophy hunting in at least a decade.

This is not what the trophy hunting community expected of Trump, despite his two eldest sons’ affinity for the practice. Last year, he tweeted:

Big-game trophy decision will be announced next week but will be very hard pressed to change my mind that this horror show in any way helps conservation of Elephants or any other animal.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 19, 2017Trump has argued elsewhere against the conservation argument for trophy hunting, which is thus: Hunters pay large sums of money to governments and conservation organizations for the privilege of hunting the animals, thus helping to fund the management and protection of the species. “People can talk all they want about preservation and all of the things that they’re saying where money goes toward,” Trump told Piers Morgan in January. He said that foreign governments probably don’t use the money properly.

Why, then, would Zinke continue on this crusade? “Safari Club International has fully infiltrated this administration,” said Anna Frostic, a senior wildlife attorney at the Humane Society, referring to the international hunting group (of which Walter Palmer, who killed Cecil the Lion in Zimbabwe in 2015, was a member).

Zinke, a lifelong hunter, has longstanding ties to SCI, stemming back to his days in Congress. He received $14,5000 in congressional campaign donations from the group, “spoke at [its] 2016 veterans breakfast, had a notable photo-op with its director of litigation on his first day as head of the Interior Department, and dined with its vice president in Alaska earlier this year,” according to HuffPost. Zinke is close with other hunting advocacy groups, too. Last summer, he received a policy wish list from eight trophy hunting organizations, asking him to roll back several Obama-era regulations on the practice.

Today, Zinke is making progress on that wish list. He’s already accomplished the first ask—to reverse the ban on lion and elephant trophies. Now, he’s working on the second request—to repeal the automatic trophy hunting protection for threatened species. The wish list, according to HuffPost, also asked Zinke “to reject a petition calling on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list all African leopards as endangered under the ESA and restrict hunters from importing their parts,” and it “called for Zinke to revise seizure and forfeiture practices that they say ‘discourage lawful tourist hunting.’”

The impact of Zinke’s policies is opaque, though, because the Fish and Wildlife Service won’t say how many animal trophies are being imported into the U.S., and who is importing them. “I’ve routinely submitted FOIA requests for precisely that information,” Frostic said. “I still don’t have a full request fulfilled from May of 2017.” Last month, the group Friends of Animals obtained documents showing that 38 lion trophies had been imported between 2016 and 2018. Of the 33 people who imported those trophies, at least half had donated to Republican lawmakers or were affiliated with SCI, the group claimed.

These actions haven’t gone completely unnoticed. In March, dozens of House Democrats sent a letter to Zinke, asking that he “halt all trophy imports, initiate a full regulatory process for the policies, make license issuances public and require annual reports from countries where FWS will allow imports,” according to The Hill. Two Democratic senators sent a similar letter. Animal welfare groups have filed legal actions against the Interior Department, too, over its decision to allow elephant trophy imports and its pro-hunting wildlife conservation council.

Trump, meanwhile, has been uncharacteristically silent on the matter.

On Twitter, where his handle is @IronStache, Randy Bryce seems like he’s already the Democratic nominee for Wisconsin’s 1st congressional district—retiring House Speaker Paul Ryan’s seat. He isn’t. Bryce, a union ironworker who found unlikely fame through a series of online campaign videos, faces a primary challenge from Janesville educator Cathy Myers. Voters will decide the winner on Tuesday.

The race has been nasty. Myers, a labor activist like Bryce, has run a negative campaign, highlighting Bryce’s history of debt and his nine arrests, including a 1988 drunk-driving charge to which he pleaded guilty. (Two arrests occurred while he was protesting Ryan and Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson, respectively.) Myers has her own baggage. The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel recently reported that she’s been accused of a conflict of interest for her involvement in a complicated, two-year legal battle between her campaign manager, Dennis Hughes, and her former boyfriend, Roger Merry, while she sat on the Janesville school board. The paper also reported that Myers may have improperly benefited from a $6,000 per year tax deduction on a home she owned in Illinois while she lived and voted in Wisconsin.

Myers could well beat Bryce in Tuesday’s primary election. In July, the Republican-affiliated Congressional Leadership Fund released a poll showing “the two terrible candidates” locked in a near dead heat, with a third of voters still undecided. CLF has a clear interest in portraying the race as a choice between two losers, but that doesn’t mean the CLF’s polling numbers are necessarily inaccurate. If Bryce loses on Tuesday, or barely wins, he’ll add a data point to an emerging trend: Viral fame can help a candidate gain recognition, credibility, and donations, but that doesn’t always translate to electoral victory.

Bryce became Internet famous more than a year ago, before Ryan had announced his retirement. Ryan was a shoo-in for re-election, and Bryce was a protest candidate—a symbolically potent one, but ultimately fated to lose. Bryce’s initial ad in June 2017, produced by Democratic strategists Bill Hyers and Matt McLaughlin, challenged Ryan’s inevitability and presented “Iron Stache” as a left-wing blue-collar champion: committed to unions and motivated by personal experience to fix America’s broken health care system. Within days, the ad had been viewed more than half a million times and raised more than $400,000 for the campaign, which followed with several more compelling ads, though few approached the popularity of his campaign announcement. By December, the campaign’s own polling had Bryce within 6 points of Ryan.

There were, and still are, challenges. According to Politico, that internal polling revealed that 79 percent of likely voters didn’t know enough about Bryce to have an opinion of him. This April, Bryce’s chances improved considerably when Ryan announced he wouldn’t run for re-election, but attacks from Myers and Republicans alike may dented his momentum. Alternatively, Bryce may have never had much real momentum at all. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to gauge the causal relationship between political celebrity and electoral viability.

The internet didn’t change campaign ads themselves, so much as change how they’re distributed. No longer do campaigns have to rely on TV, blindly running ads that in the hopes of connecting with voters. Today, campaigns know in a matter of days—sometimes hours—whether an ad is resonating with people. If no one is watching and sharing it, the campaign can cut a new one tomorrow.

But is the ad connecting with the right people—actual voters in the district rather than political junkies across America? That’s harder to know.

Thematically, Bryce’s ads bear some resemblance to Democratic candidate Amy McGrath’s debut ad for her primary run in Kentucky’s 6th congressional district. McGrath’s ad, which has been viewed nearly 2 million times, was produced by Democratic strategist Mark Putnam and documents her experience as the first female U.S. Marine to fly an F-18 fighter jet in combat. The congressional campaigns of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Kaniela Ing of Hawaii also made ads—both produced by Means of Production, a democratic-socialist production company—that went viral, racking up over 580,000 and 442,000 views, respectively. Neither ad appeared on television.

McGrath won her primary. Ing trended on Twitter the day of his primary, but pulled just 6 percent of the vote. Ocasio-Cortez has emphasized the success of her door-to-door canvassing efforts, rather than her videos, as key to her upset of Congressman Joe Crowley. Other left-wing candidates did well without ever going viral. Rashida Tlaib’s most popular video on YouTube has barely more than 3,000 views, but she just won the Democratic primary in Michigan’s 13th congressional district. Paula Jean Swearengin, an environmental activist in West Virginia, lost her primary challenge to incumbent Senator Joe Manchin, but she managed to get 30 percent of the vote without even producing an ad, it seems.

If viral ads reliably accomplish anything at all, perhaps it’s a different kind of political work. Ing’s last ad, which Slate called “the most remarkable political ad of 2018,” might be the clearest example. “If you ask people the question, ‘What would you do if you didn’t have to worry about finances and you had your basic needs met?’ the answers are amazing,” Ing says, while strumming a ukulele on a beach. “People would start businesses. They’d get into art, they’d get into music and all these things that are lacking in our world. All this stuff is possible.” Ing’s ad didn’t win him the election, but it did advance his ideas. It expanded people’s political imagination. So have Bryce’s ads, whether or not he wins on Tuesday.

This weekend, headlines across the internet announced that the British Museum was to “return looted antiquities to Iraq.” Eight tiny artifacts, some of them 5,000 years old, were handed to Iraqi officials in a ceremony on Friday, to be transported to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. But the antiquities were not, as the headlines implied, a part of the British Museum’s own collection; they were just identified there after police seized them from a dealer. The distinction is crucial, because the Museum houses one of the largest permanent collections of human culture on earth, some of which came from the old-school kind of “looting”—colonialism.

According to the Museum’s press release, the objects consist of an Achaemenid stamp seal; two stamp-seal amulets “in the form of a reclining sheep or showing a pair of quadrupeds facing in opposite directions”; and five Sumerian artifacts. Three of these objects are clay cones inscribed with the sentence, “For Ningirsu, Enlil’s mighty warrior, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made things function as they should (and) he built and restored for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” The inscription locates the objects as originally part of the Enninu temple of the Sumerian god Ningirsu.

The objects were seized by the London police in 2003 from a dealer who could not provide proof of ownership (and who is no longer in business). They were not among the treasures stolen from the National Museum of Iraq in 2003, but rather come from Tello in southern Iraq, where the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu once stood. The press release emphasized that the objects were identified “thanks to the British Museum’s Iraq Scheme,” which was founded in 2015 “in response to the appalling destruction by Daesh (also known as so-called Islamic State, ISIS or IS) of heritage sites in Iraq and Syria.” The program “builds capacity in the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage by training 50 of its staff in a wide variety of sophisticated techniques of retrieval and rescue archaeology.”

British Museum director Hartwig Fischer shakes hands with Iraq’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, Salih Husain Ali, during the handover ceremony.British Museum

British Museum director Hartwig Fischer shakes hands with Iraq’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, Salih Husain Ali, during the handover ceremony.British MuseumThe scheme is no doubt an important one, and the region’s artifacts have been, no doubt, in danger. But as the media picked up the story of the handover, a strange impression arose: that the British Museum gave something back. The British Museum never gives anything back.

The story recalls last year’s flurry of articles promising the British Museum’s return of ancient sculptures to Nigeria and Benin. The Benin bronzes, as they’re known, were looted by the British in 1897 while they destroyed Benin City. The destruction was meted out as punishment for Oba Ovonramwen’s defiance, as he insisted on charging the colonizers custom duties. The Guardian and other outlets described excitement over a summit, planned for 2018, during which the British Museum might hand back the stolen treasures. British officials this year have so far only offered to loan the artifacts to Nigerian museums.

Many items in the Museum’s collection have similarly dodgy histories. In 2015, an exhibition called “Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilization” displayed items acquired after the British occupied Australia in the early eighteenth century and, over the course of the next 200 years, massacred thousands of its aboriginal inhabitants.

The most famous controversy over the Museum’s collection centers around the so-called “Elgin marbles,” named for Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, who obtained treasures of the Parthenon as a favor from the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and transported them to England. The longstanding argument for his actions, both then and now, is that the marbles were moved in order to preserve their integrity. Though this argument is not without its merits (and its holes), it’s not the overarching issue for British authorities. The real problem, I think, is the scale of restitution that could open up once a precedent is set. Responding to India’s call for the return of the Koh-i-noor diamond in 2013, for example, former Prime Minister David Cameron said, “I certainly don’t believe in ‘returnism,’ as it were. I don’t think that’s sensible.”

So, reading the news that the British Museum would “return” anything came as something of a surprise. The British Empire’s violent colonial actions are not regularly subject to re-examination. Tony Blair said in 1997 that the empire should be the subject of neither “apology nor hand-wringing.” In 2011, Cameron told his party that “Britannia didn’t rule the waves with armbands on” (armbands are British for floaties). It was 2013 before the U.K. acknowledged its torture and murder of the Mau Mau people in the 1950s, and agreed to pay compensation to survivors.

This week’s headlines invoked a fantasy version of the British Museum’s role in international relations. The director of the museum may have shaken hands with Iraq’s ambassador to the U.K., but he has not performed a genuine act of restitution. The British Museum has been styled in the press (and styled itself in its own press release) as a bulwark against looting. But the museum is a cathedral to the practice. The presence of the rest of the collection cast a long shadow over proceedings on Friday, and it showed the “return” for what it was: A simple case of stolen goods, intercepted.

Florida’s Senate race, where incumbent Democrat Bill Nelson has been steadily losing ground to Republican Rick Scott, could decide which party controls the Senate next year. And at the moment, it seems to hinge on an unusual issue: algae.

The state is dealing with one of the worst algal blooms in its history. A noxious “red tide” has coated 100 miles of beaches along the Gulf Coast with sludge and the carcasses of thousands of fish, sea turtles, and manatees. A 26-foot whale shark even floated ashore earlier this month—the first ever, The Washington Post reported, to be killed by algae. The crisis hasn’t just driven away tourists and hurt local businesses. It’s caused respiratory illnesses, headaches, rashes, and gastrointestinal distress all along the Florida coastline.

Now, both Scott and Nelson are campaigning on the algal bloom, laying the blame on each other in TV ads and in speeches. Though it would appear to be a local issue, it touches on a range of issues—deregulation, the environment, cronyism—that are playing out at the national level. And for Democrats looking for a foothold in the rapidly reddening South, where some of the nation’s most pressing climate and environmental issues have become a daily reality, the urgency of environmental action may provide the blueprint for competing in heavily Republican districts.

The crisis in southwest Florida is a familiar one, even if its scale is unprecedented. Lake Okeechobee, southern Florida’s largest lake, fills up with pollution from the nearby sugar plantations every year. When rains hit in May, the lake swells behind a feeble and aging dike, and the Army Corps of Engineers, needing to protect the nearby towns, releases the slurry to the ocean. This year, however, record rains combined with the heat and a warmer-than-average Gulf to create an algal explosion of historic proportions. The current red tide has already lasted longer than any other in over a decade, with no signs of abating.

In response, Rick Scott, who is serving out his last term as governor, announced that he’d be touring the blighted St. Lucie River region and earmarking an extra $700,000 to the clean-up efforts. Protesters filled the dock hoping to meet with the governor, but Scott refused to speak with them or the media. He ended up embarking on his boat tour from a different location than was initially announced, peaking frustrations even further.

Scott has long been a target for environmental protesters. After his election in 2010, he wasted no time bulldozing environmental protections that had been decades in the bipartisan making. He gutted the state’s five regional water management districts, slashing their budgets by $700 million and packing their appointed boards with developers. He oversaw the firing of 134 employees at Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection. Taking up the mantle of big polluters, he battled and eventually bested the EPA on the implementation of clean water standards.

In 2012, Scott killed a statewide septic tank inspection program and an initiative that would’ve rehabilitated polluted freshwater springs. His appointees on the enfeebled South Florida Water Management District scuttled plans to buy 46,800 acres of sugar company land where the state had once planned to build giant retention ponds to store and filter polluted lake water. Under his watch, spending for Florida Forever, the state’s land conservation program, plunged from $100 million a year in Scott’s first year to a paltry $17 million by 2013. And in 2016, Scott signed into law weaker standards for toxic chemicals that flow into Florida’s rivers, lakes, and coastal waters, a bill described as allowing “Big Ag to police itself when it comes to fertilizer pollution.”

Any of these protections could conceivably have mitigated the damage now being visited upon the southern Florida coastline and its residents. Instead, more pollution, less oversight, and a depleted budget for remediation set the stage for the current algal explosion.

One might expect Nelson’s campaign to be hammering Scott on the issue: They have ample material, ready to be spliced together in attack ads that touch on his environmental record and coziness with the state’s most egregious polluters. In recent years, the Republican governor has accepted over $600,000 from the sugar industry. In 2013, he took a trip to King Ranch in Texas, a famous private hunting lodge, for which Big Sugar generously footed the bill.

But it was the Scott campaign that struck the first big blow, running an ad last week that laid responsibility for Lake Okeechobee and the algal blooms at Nelson’s feet.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which manages the lake’s dike, is a federal entity, so Nelson, the ad suggests, is to blame based on his time in the Senate. Five days later, the Nelson campaign punched back with a 30-second, text-over-video spot of its own titled “Algae.” “Rick Scott cut environmental protections and gave polluters a pass,” the ad proclaims in block letters atop a slideshow of sludge. “The water is murky, but the fact is clear.”

Unfortunately for Democrats, Nelson isn’t in the strongest position to criticize Scott. He’s proposed bills to study algae, cut Lake Okeechobee discharges, and automatically authorized the Army Corps to start Everglades restoration projects without congressional approval, but none of them has been successful. And when eleven environmental groups petitioned Nelson to get on board with the bipartisan Sugar Policy Modernization Act, which would have curtailed some of the sweetheart price guarantees the sugar industry currently enjoys, Nelson declined.

In fact, campaign finance records show that for 2018, only four senators have accepted more in contribution money from Big Sugar than Bill Nelson. (One of them is fellow Florida Senator Marco Rubio, the only Republican on the list.)

Still, the fight over the algal bloom shows that Democrats can leverage environmental issues into powerful campaign messages. With climate-fueled crises breaking out in every corner of the country, from fires in Northern California to heatwaves in the Midwest, there has never been a better moment to hammer a candidate who forbade his employees from using the words “climate change” at all, as Scott infamously did. This is especially the case with public opinion beginning to coalesce around climate issues. A recent survey found that 73 percent of Americans now believe there’s solid evidence of global warming, and 60 percent think it’s due to human causes, a notable increase since 2010, when Scott first took office.

The issue is particularly salient in the South, the American region hit hardest by climate change and home to the country’s laxest environmental standards. “We think an emphasis on environmental issues will benefit Democrats up and down the ticket, especially as Florida continues to be inundated by flooding from hurricanes in the last few years, with millions of gallons of sewage going into our waterways, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico,” notes Jake Sanders, the president of the Florida Young Democrats.

In swing states like Florida, where Donald Trump won by 100,000 votes, as well as environmentally afflicted red-wall states like Louisiana, there are millions of Americans for whom a robust green policy charter could be attractive. “People in these places understand that things are changing rapidly right in front of their eyes, and it’s raised awareness to a level it’s never been before,” says Denis Dison of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Action Fund.

To pull off such climate-focused campaigns, though, Southern Democrats, particularly in states like Florida, have to take strong stances on climate issues. Nelson has bright spots on his environmental record—he fought to ban oil drilling off the Florida coast, and he sported a 95 percent voting score from the League of Conservation Voters in 2017. But he would be in a far stronger position on the red tide crisis if he’d endorsed a bolder spate of green policies, such as a major remediation plan for Florida’s waterways and stiffer punishments for polluters.

There are signs that he’s taking the hint. During a recent visit to one of Lake Okeechobee’s most polluted waterways, Nelson, more wonk than firebrand, mustered this: “I was playing nice-nice when I was here before, but I’m going to lay out the truth. Governor Scott, in the last eight years, has systematically dismembered and dismantled the environmental agencies of the state of Florida.”

It was Chinese New Year, a weeklong celebration of fireworks

and family to scare up good fortune and dispel evil spirits, when the killer

went on the prowl again.

He picked a young worker walking home, and followed a ways behind. He’d done it before, many times, enough to perfect his technique, but things did not go as planned that winter’s night. His crimes were already notorious and the target realized the danger; she fought back tooth and nail, locked the door, and frantically called her husband.

It was then, she said, that her would-be killer reappeared, grinning outside her window. When her husband reached her, the couple checked again: there he still was, still laughing. By the time police arrived, though, the smiling apparition had vanished into the New Year’s night, blending into the carefree popping of corks and firecrackers—and the 14-year pall of fear and suspicion one phantom had managed to cast over a remote city of 1.7 million in the world’s largest authoritarian country.

“Our parents used to talk about it sometimes,” Sun, a friend who grew up near the northeast city where at least one of the killings occurred, told me. “When we were growing up, kids weren’t allowed to go out after dark… and my mom never let me wear anything red.”

Between 1988 and 2002, multiple women were murdered in the cities of Baiyin, Gansu province, and Baotou in Inner Mongolia, some five hundred miles to the northeast. Media reports on the crimes would come under the strict control of China’s propaganda departments and, even today, outsiders reporting on the subject are met with a near-impenetrable wall of silence. Still, stories spread: the victims were young, female, pretty; their bodies had been horribly desecrated; the killer was said to favour long-haired girls, in high heels, wearing red. Only some of these tales were true—but they were the worst ones.

In August 2016, nearly three decades after the killings began, and after years of inactivity from the killer, police sensationally revealed the most unremarkable suspect: Gao Chengyong, a 52-year-old recluse who shared a campus grocery store with his wife. Gao quickly confessed, Chinese media reported. Suggestions that there may have been other survivors, or that Gao had killed more, came to naught. During sentencing in March of this year, prosecutors addressed only the official charges: the rape, mutilation, and murder of 11 women. In the two years since Gao’s arrest, the reasons for his crimes have remained as elusive as the killer himself—a function both of the inscrutable perpetrator and a compulsively secretive law enforcement, reluctant to talk about a period in which Chinese forensic methods had yet to catch up with behavior unleashed during decades of rapid and chaotic economic development.

Why had Gao suddenly stopped in 2002? The botched encounter in 2001 was one possibility; growing family pressures another. The killer was getting old, less able to subdue young women. Remarkably, he’d even acquired a reputation for filial piety among his naïve neighbors, having nursed a sick father and raised two children. His eldest son was born back in 1988, the same year the killings began.

His first victim was 23. Her body had 26 knife wounds. At 24, Gao was only one year older than Bai, whose friends and family always called her “Little White Shoes.” He would later claim it was only meant to be burglary when he broke into the factory bungalow where her family lived. But Bai woke, and Gao struggled to silence her, ultimately strangling her to death. Her brother, in his room just a few feet away, never heard a thing; the volume on Bai’s snazzy new tape-deck was turned up all night. Gao sat after, leafing through Bai’s photo album, staring at the girl’s frozen image for hours; then he destroyed the pictures and went home to his pregnant wife. Burn after reading: it would become a pattern. But six years apparently went past without him killing again in Baiyin; meanwhile, the city itself began its own slow death spiral.

During the Mao era, Baiyin had been a flagship of the planned economy, an industrial powerhouse built on wealth from copper ore. Miners and metalworkers were dispatched from across China to help exploit the rich seams found in this impoverished region’s dusty bowels; women from other work units were sent afterward to join them, and start families. After a while, the city flourished: “Baiyin Metals employees were the city’s trendsetters,” reported Shanghai-based media startup Sixth Tone. “They were the first to have perms, turtleneck sweaters, bell-bottom pants, whatever was popular at the time.” As one resident put it: “The people of Baiyin were different from those of other parts of Gansu.”

Community bonds were stronger in mid-century Baiyin, too, partly due to the collectivist spirit of the age, but also because social mobility was strictly limited by the country’s household registration (hukou) system, which tethered almost all Chinese to their birthplace. During the gold rush years, the restrictions gave few reason to worry. But by the mid-1990s, the copper-producing region was barely recognizable to those who remembered its heyday. Like the U.S. in the late 19th Century, China was rapidly industrializing, and undergoing seismic societal shifts. The “traditional family style of living”—a Confucian ideal of “four generations under one roof ... where everyone kept an eye on each other” began to break up, as international forensic scientist Dr Henry C. Lee explained in a phone interview from New York; old hukou restrictions were relaxed, giving a vast and itinerant blue-collar population access to newly developed routes and infrastructure, as railroads, freeways, and ports—and, just as in the U.S., where early 20th century murderers like the Cleveland Torso Killer, Chicago’s H.H. Holmes, and the Mad Axeman of New Orleans began preying on a ready supply of “low end” migrant populations (day laborers, runaways, vagrants, sex workers, addicts), the age of the serial killer was dawning in China.

As Baiyin’s ore started to run out towards the end of the 1980s, the prosperous mining town lost its luster, and began to resemble those other moribund parts of the state-run economy that were being unsentimentally dismantled during a fresh swathe of economic reforms. The city’s wealth and revolutionary image tapered off, its sense of communal prosperity gradually replaced with rising unemployment, youth gangs, mass migration.

The second killing came on a July afternoon in 1994, when a 19-year-old cleaner disturbed a man wandering the dormitories at the Baiyin Power-Supply Bureau. Gao slit her throat and stabbed her 36 times. Four years after, a 29-year-old third victim was found naked with 16 wounds and a fresh signature: parts of her scalp and ears were missing. Only three days later, Gao killed again, this time taking portions of his victim’s breast and torso.

Returning to Baiyin’s Power-Supply Bureau on July 5, Gao encountered eight-year-old Miao Miao at around six in the evening, waiting for her parents; he raped the child, strangled her with a leather belt, then poured himself a cup of tea from a flask on the kitchen table. Later, police would ask how old Gao’s own son was at the time. Ten, he replied. “I stared at him, and he stared back for almost ten seconds, before lowering his head,” the interviewing officer told the Beijing News. “My fist was raised [and I] almost slammed it into his face.”

The relatives of a victim of Gao Chengyong stand in front of the at the People’s Intermediate Court of Baiyin City in Baiyin, China, during his trial on March 30, 2018. Imaginechina/AP Photo

The relatives of a victim of Gao Chengyong stand in front of the at the People’s Intermediate Court of Baiyin City in Baiyin, China, during his trial on March 30, 2018. Imaginechina/AP PhotoFour months later, factory worker Cui Jinping was found by her mother in a pool of blood, her body horribly mutilated. It was Gao’s fourth kill in a single year, and the city was now in full panic: Police began sweeping neighborhoods, conducting door-to-door interviews, tossing apartments, in a desperate hunt for witnesses or clues.

Meanwhile, and perhaps unwittingly, authorities were sitting on a motherlode of evidence—DNA samples collected from multiple crime scenes. At the time, forensic analysis was still in its infancy, with budgets extremely tight. Indeed, up until the mid-1980s, most Chinese police did not have proper uniforms, stations, squad cars, or tactical equipment. It was only in 1983, after a pair of gun-toting homicidal brothers went on a six-month robbery spree that left over a dozen dead and wounded in their wake (including several soldiers and officers), that the government realized its newly emerging capitalist society would need serious and well-funded policing.

In northeast China in the mid-90s, demand for rigorous policing still far exceeded supply. Factory closures had left millions without jobs or the skills to find new ones; there was mass unrest in many places, most meeting with swift reprisals from the state. Lacking social security, many resorted to petty crime to get by. And in the chaos, those inclined to darker deeds could operate with relative freedom.

By 1994, there were “almost certainly several serial killers” aside from Gao at large in the area, according to one source in the regional public security bureau, who spoke on strict condition of anonymity. They described a region where unemployment, despair and lawlessness abounded, and life was short and cheap. “The murder rate was very high at that time”—certainly much higher than any official figures show—“and many people did terrible things.” Only in the last decade or so has law managed to reassert itself in some of these remote and often-depressed districts.

But after the killings in 1998, the brief surge in street-level policing did manage to scare at least one of Baiyin’s bogeymen into temporary hiding.

Gao Chengyong was born in 1964, in Chenghe, a small county in Gansu, a perpetually poor province. Questioned by Chinese media after the arrest, his neighbors struggled to recall much about the quiet youngster; certainly, Gao didn’t much take to the agrarian life. By his late teens, he’d joined the sea of restless workers taking advantage of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and a more relaxed houkou system, which previously had strictly curtailed internal migration. In this new era, low-skilled laborers were able to take work where they could, moving on when they couldn’t, though the houkou still restricted their rights: A migrant like Gao could live in a place like Baiyin, but not access the benefits of better education, health, social security that such cities afforded. This caste-like policy enabled China’s emergent urban middle-class to enrich themselves on the backs of a largely disenfranchised and docile labor force that did most of the hard work. For most, the houkou was a social trap. For some, though, it proved a license to roam, adventure—or in Gao Chengyong’s case, to kill anonymously, an unregistered rogue amidst the closely monitored masses.

The courtyard of Gao Chengyong’s family home on August 28, 2016, in Chenghe Village, Gansu, China. VCG/VCG/Getty

The courtyard of Gao Chengyong’s family home on August 28, 2016, in Chenghe Village, Gansu, China. VCG/VCG/GettyGao was one of many “disorganized” murderers now roaming the country, with some amassing startling body counts: There was “Monster Killer” Yang Xinhai, who broke into farmhouses and killed all occupants, totaling 65 victims; Peng Maiji who used a meat cleaver to murder 77; Wu Jianchen, who killed 15; and Wang Qian, with 45 known victims. The apparent absence of motive, and arbitrary distribution of their crimes baffled police. Judicial disinterest, and jurisdictional restrictions, ensured that many murders were never even linked at the time. While the public remained largely in the dark about such threats, police were, at least, able to associate the Baiyin killings with a single suspect, even if he continued to elude them.

Though pressed into inactivity after the policing surge, Gao’s restraint lasted no more than a few years. He “just felt the need to kill someone,” he later told police. His methods were neither particularly organized or clever, as he afterwards admitted. While the rumors had insisted he had a fetish for red clothing or long hair, Gao later confessed he had merely wandered the streets in a fitful rage, choosing victims for their “appearance and suitability.” The post-mortem mutilations became his revenge for their initial resistance; he took care to don dark clothing to mask any blood spatter. In May 2001, a few months after his failed Spring Festival assault, Gao attacked and killed a 28-year-old nurse at her home, near the same address as his fourth victim.

Police enlisted eight specialists from the Ministry of Public Security, including Zhang Xin, Senior Engineer of Criminal Technology at the Shanghai Railway Public Security Bureau and an expert in facial composition. Gao’s bungled 2001 assault had left behind not just a terrified couple, but a police officer who’d observed a similar-looking suspect en route to the scene. Based on their descriptions, Zhang Xin produced a triptych of portraits. But his illustrations were only used internally, withheld from the media to avoid, in Zhang’s words, “a negative impact on the investigation.” Police launched a citywide dragnet collecting fingerprints from over 100,000 men, using the portraits as a reference. Although this effort represented the authorities’ most concerted attempt yet to catch the killer, the public never saw them.

Their efforts led nowhere. Gao’s last confirmed victim would meet her end on February 9, 2002, about a year after he’d failed to force his way into the young woman’s apartment. Twenty-five-year-old Ms. Zhu had been rooming long-term at the fleapit Taolechun Hostel before she had the misfortune to run into Gao. Her decomposing body was found 10 days later, stripped, raped, her throat cut. Afterward, Gao had gone home, perhaps alone, or to his wife or one of his sons, who usually saw him only once a year, around Spring Festival; one of the times he liked to hunt.

It would be his final crime. Perhaps, at 38, the homicidal urges had waned along with his physical strength. Since his arrest in 2016, though, Gao has proved a case study in disinterested sociopathy; asked why he took a first six-year hiatus after 1998, he told investigators he “didn’t know.” Gao has given only detailed recollections of his actual crimes, all delivered with a deadpan disposition. “Gao’s calmness is unimaginable… terrifying. He remembers everything clearly,” one interviewer said. But he has offered no clue as to motive—or how he eluded the manhunt for nearly three decades.

Gao Chengyong stands trial on March 30, 2018 in Baiyin, Gansu Province of China. VCG/VCG/Getty

Gao Chengyong stands trial on March 30, 2018 in Baiyin, Gansu Province of China. VCG/VCG/GettyOnly a mixture of fortune, fortitude, and forensic science caught up with him. After the murders ceased in 2002, detectives were left flailing. Many of the original crime scenes had been trampled on by a parade of rookie cops and officials, and fingerprint comparisons still involved step-by-step inspections with a magnifying glass; lead investigator Zhang Enwei says his team personally combed through over 230,000 sets of prints. In addition, profilers had advised police to look for a loner with a “sexual perversion … [who] hates women …reclusive and unsociable, but patient.” As a shopkeeper with two children, Gao seemed to be a model migrant, a married man who’d nursed his dying father through sickness and sent his sons to college.

“There was very little physical evidence,” as Detective Zhang Enwei told the Beijing News. On guard against all media while their investigation was ongoing—those working on the case had been instructed that any leaks would lead to instant dismissals, and see the case transferred to a different department—officials have only hesitantly opened up to local reporters since Gao’s arrest. Foreign reporters are almost universally shut out, for fear that officials will be punished if their name appears in an overseas article offering a negative impression of China.

Asked to be interviewed for this story, Detective Zhang declined, as did eight other experts. Gao’s own lawyer first agreed, then a week later pulled out, saying “leaders” had forbidden him from contacting foreign media. “People in the public security system are extremely wary of foreigners,” an intermediary of Zhang’s explained. “You can file a formal application through the police bureau”—an action tantamount to feeding it through a shredder.

“Estimating how many actual serial killers there have been in China is impossible.”Nervousness about the media, and foreigners in particular, has increased during Xi Jinping’s presidency. The secrecy extends to all levels of policing, including statistics. “Countries such as China do suppress information about crime,” Dr. Mike Aamodt, who compiled the Radford University/FGCU Serial Killer Database, told me. “One must be very cautious in interpreting any crime statistics from these countries—including the frequency of serial murder.” There are only 62 known serial killers in China, according to Dr. Aamodt’s latest statistics, which must rely on “Internet and English media sources” rather than public documents and court records. That’s to be compared to 3,376 known serial killers in the U.S., a population of over 325 million. “Estimating how many actual serial killers there have been in China is impossible,” Dr. Aamodt admits. “I would not be surprised if the actual rate is similar to the rate in the United States.” If it were, a population like China’s, over four times that of the U.S., could expect over ten thousand serial killers—not 62.

Chinese law enforcement, once dependent, according to Dr. Lee, on “traditional methods of interview and interrogation,” has advanced at a dizzying rate in the last two decades, “training [detectives] to international standards” and installing “laboratory facilities more advanced than many in the world.” Still, it wasn’t until 2010 that a proper forensics laboratory was established in Baiyin, and science could finally catch up with Gao and his DNA—or rather, his cousin’s. While their suspect had studiously spent years avoiding any involvement with authorities, a relative arrested on minor corruption charges in 2016 had given a swab. Computers found a familial match to some of the DNA from the crime scenes, and a task force was assembled to monitor their chief suspect, now working ostensibly as a campus shopkeeper, maintaining his quietly forgettable profile. “Everyone thought [Gao’s wife] was single, because she was the only one ever working,” a teacher told the Lanzhou Morning Post. Even if Gao hadn’t been so reclusive, who would connect the balding “serious looking” shopkeeper that staff remembered with the “murderous madness” of their youth, when nervous schoolgirls would return home over half-term rather than stay and study?

Prosecutors finally presented their case against Gao in July 2017, following an unusual year-long preparation: Prosecutors had to ensure “there are no false positives,” Gao’s lawyer, Zhu Enwai, explained, “Just in case, years later, someone jumps out and says ‘That was me.’”

At the end of a two-day trial at the Baiyin Intermediate People’s Court in Gansu, Gao stood and bowed thrice to his victims’ families, then bizarrely offered to donate his organs. Lacking any explanation, Gao’s act of ritual contrition appears as meaningless as his crimes. And without context or public follow-up, his crimes seem as arbitrary as his capture. But the only eyewitness to his assaults recalled a very different Gao Chengyong than the man who would reappear expressionless, in T-shirt and jeans, to offer his remorse and be sentenced to death in March: a sadist who stood outside her window, defiant, laughing.

Two years ago a New Scientist headline announced the “world’s first baby born with new ‘3 parent’ technique.” Whereas an embryo is usually produced by one sperm and one egg, this technique uses genetic material from three separate people. First performed by a New York fertility clinic in Mexico to evade US legal restrictions, the procedure has now been replicated several times. A clinic in Ukraine started offering a similar procedure in late 2016 (albeit on shaky ethical and medical grounds), while regulatory authorities in the United Kingdom approved its use for two women earlier this year.

THE TANGLED TREE: A RADICAL NEW HISTORY OF LIFE by David QuammenSimon & Schuster, 480 pp., $30.00

THE TANGLED TREE: A RADICAL NEW HISTORY OF LIFE by David QuammenSimon & Schuster, 480 pp., $30.00The cases in the UK and Mexico each involve a woman who carries a rare disease of her mitochondria, the cellular structures that produce energy in our cells. Mitochondria have their own DNA and can harbor their own genetic diseases. These are passed on solely through the maternal line, because mitochondria are found in eggs but not in sperm. One approach to blocking transmission of these illnesses involves inserting the DNA-filled nucleus from the egg of the woman into a donor egg full of healthy mitochondria but stripped of its own nucleus. Fertilize that hybrid egg with a sperm, and presto! A child could be born nine months later with DNA from three people and without a catastrophic mitochondrial disorder.

This result could be a blessing—but the science behind it sounds confusing. Isn’t DNA supposed to be our sacred blueprint, wound up in chromosomes and locked up safely in the nucleus of our cells? What are these mitochondrial creatures doing with their own DNA, replicating within our cells and bequeathing diseases to our offspring? If they seem like invaders, it’s because they once were. Mitochondria, it turns out, were originally bacteria; their free-wheeling existence came to an end one day deep in evolutionary history when they entered another single-celled organism and started a new life inside. That receiving cell was the ancestor of all animals, plants, fungi, and protists. The origin of the mitochondria is reflected in the basic shape of its DNA: It is looped in a simple circle, just like a bacteria’s, unlike the linear chromosomes found in our nuclei.

Children conceived with a third person’s mitochondria are, it follows, the offspring of three parents, but the third parent is, in at least some sense, the descendant of an ancient bacteria. After those bacteria took up residence in our common ancestor, they proceeded to swap genetic material with the nucleus, further blurring the boundaries between host and invader, self and other over the eons.

This is not what we think of as Darwinian evolution, the transmission of genes and traits down the family line. DNA, it turns out, can also be passed laterally, between individuals, including those of different species. This discovery represented a tectonic shift in our understanding of nature, a story that David Quammen tells wonderfully in his exhaustively researched book, Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life. Crisscrossing the country to interview scientists and visit labs, Quammen provides a vivid portrait of the scientific process, and of the quarrelsome, quirky, (in one instance) evil, and brilliant scientists behind it. We may like to think of DNA as the neat bequest of our parents, the fusion of two unique, circumscribed human lineages. Yet it is—and we are—something more: short strands within a vast interwoven genetic web, stretching back to the earth’s earliest days, linking all living things.

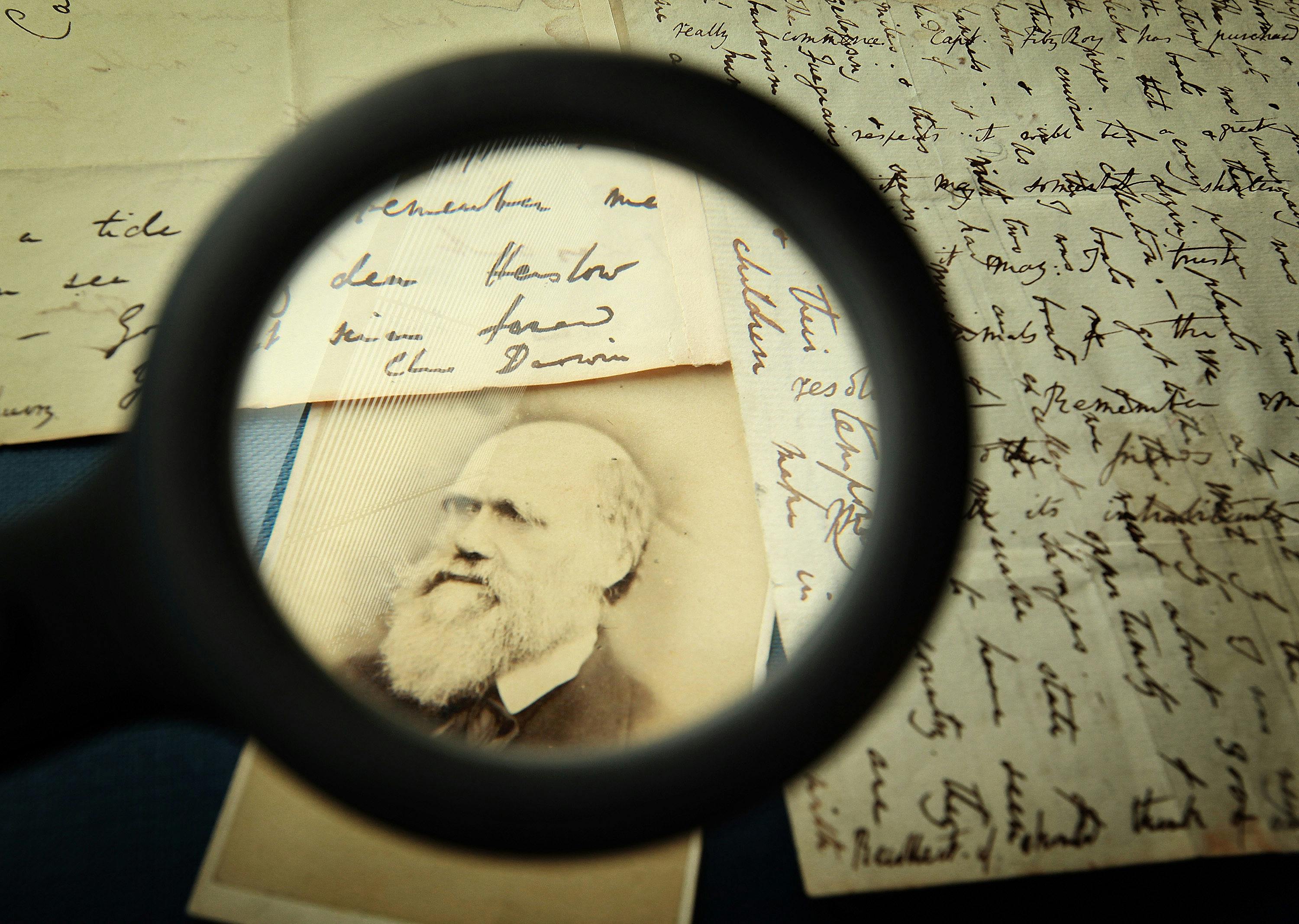

Quammen’s story starts with Charles Darwin, who—well before publishing On the Origin of Species—jotted down a historic sentiment in a notebook: “organized beings represent a tree.” Although it was a long-established concept (it had precursors in both the bible and Aristotle), Darwin’s version “was a thunderous assertion, abstract but eloquent.” His Tree of Life suggested a common ancestor at the tree’s trunk and ever-dividing branches leading from it to new species. It became the standard pictorial representation of evolution until, as Quammen notes, “a small group of scientists would discover: oops, no, it’s wrong.”

One important strand in this story was the discovery of endosymbiosis: the fact that mitochondria—together with chloroplasts, the structures in plant cells that convert sunlight into food—were once bacteria that started a new life within our cellular forefathers. One of the theory’s earliest and most influential proponents, as Quammen tells it, was a nefarious Russian scientist named Constantin Sergeyevich Merezhkowsky. Merezhkowsky fled from the Crimea in 1898, likely because he was a child molester, and wound up in California, where he studied a single-celled alga that performed photosynthesis (while writing some bizarre science fiction on the side). His work led him to embrace the (unproven) hypothesis that chloroplasts in the algae were, in fact, ancient invaders. He would commit suicide in 1921 in a hotel room in Geneva, but his theory lived on, in obscurity.

It was revived decades later by a prominent, controversial scientist named Lynn Margulis. In 1970, Margulis published a book, Origin of Eurayotic Cells, that expounded a modern version of endosymbiosis. Some saw her theory as brilliant, while others, Quammen writes, “thought she was nuts.” She was ultimately proven right, by another scientist, Fred Doolittle, in Nova Scotia. He and his collaborators analyzed an ancient cellular structure called the ribosome (responsible for building all the cell’s proteins) to prove that both chloroplasts and mitochondria were indeed “foreign” species. They, in turn, relied on techniques innovated by the main character of the book, the complicated, conservative, and grudge-bearing Carl Woese of the University of Illinois.

Woese was a scientist who helped radically redraw the “Tree of Life” like perhaps no other in the twentieth century. Among other things, he and colleagues “discovered” that there was an entirely new type of life known as the “archaea.” Even Woese, however, was mostly left behind by the next big paradigm shift—the discovery of “horizontal gene transfer.”

Horizontal gene transfer gives us new ways of understanding many phenomena. One is the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. When treating a serious infection, physicians will typically send a sample—whether of pus, phlegm, urine, or blood—to the laboratory. Within a couple of days, a report comes back, with the name of the bacteria and a list of what can be used to kill it. Next to each antibiotic on the list will be one of three letters: S (“sensitive”), I (“intermediate”), or R (“resistant”). Depending on the bacteria, there may be mostly S’s, but sometimes a glance at the report produces a queasy sensation. Perhaps there are very few S’s; maybe, there is none.

Darwinian evolution, of course, can explain the rise of antibiotic-resistant bugs. It happens like this. A colony of bacteria gets doused in a deadly antibiotic. Amidst the die off, one bacterium has a lucky mutation that, say, lets it manufacture a molecule that can pump the antibiotic safely out of its cytoplasm into the surrounding slime. That lucky guy thrives and divides and replaces its massacred brethren, and gives rise to a new and nastier colony impervious to the antibiotic. Or as Darwin cheerfully put it On the Origin of Species, “the vigorous, the healthy, and the happy survive and multiply.”

Life, in other words, is not just a history of divergence, of the sprouting of new forms from a solid trunk. Sometimes, life converges.So far so good, for the bacteria

anyway. But unfortunately for us (and unknown to Darwin), bacteria possess

another means to acquire antibiotic resistance without having to sit around

waiting for the next lucky mutation: They can swap genes the way we share

recipes. When one bacterium rolls up close to another—not necessarily even of

the same species—it can share a chromosome containing a slew of genes with,

say, an enzyme that can smash penicillin into pieces.

Horizontal gene transfer is much more than a way for bacteria to share antibiotic resistance genes; it happens throughout nature and in the history of living things. We are all, for instance, partially viruses in a sense: Eight percent of the human genome arrived to us from the outside, from retroviruses, as Quammen notes. Various studies suggest that many of our genes were acquired, horizontally, from bacteria. Life, in other words, is not just a history of divergence, of the sprouting of new forms from a solid trunk. Sometimes, life converges. From this perspective, those three-parent children are no more unusual than you are or I am.

Ultimately The Tree of Life is merely a metaphor, but I think a pleasant one: It connects us to the lineage of all living things, all the way back to the bag of chemicals—or maybe the single molecule—that one day coalesced in the primordial muck. Yet like all metaphors, the “tree” falls short of reality. For in biology, all boundaries are blurred: between species, sometimes even between individual organisms, and probably between the living and the non-living.

No comments :

Post a Comment