On a frigid December day in 2017, Oleg Kalugin opens the door of his house in Rockville, Maryland, an upper-middle-class suburb of Washington, D.C., to meet me. Nothing in particular distinguishes his split-level suburban home from those of the other professionals in the neighborhood, but the man who lives there is very much out of the ordinary, a former KGB spymaster who is now an American citizen.

Born in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), Kalugin, at 83, now lives just half an hour’s drive from the White House, which for decades was dead center in the crosshairs of the KGB, the dreaded secret security forces he served as head of counterintelligence. A genial host, Kalugin gives a guided tour of his sprawling library spread over three rooms and reveals himself to be a man of history, a veritable Zelig of the Cold War.

When it comes to Soviet leaders Yuri Andropov, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Boris Yeltsin, Kalugin knew them all and can regale you for hours with stories about them. He was even the boss of a promising young KGB officer named Vladimir Putin.

Of medium height, immaculately groomed, clad in dark blue slacks, a striped shirt, and a light blue jacket, Kalugin was congenial and utterly disarming when I met him. As John le Carré wrote, when he interviewed Kalugin nearly 25 years ago, he is “one of those former enemies of Western democracy who have made a seamless transition from their side to ours. To listen to him you could be forgiven for assuming that we had been on the same side all along.”

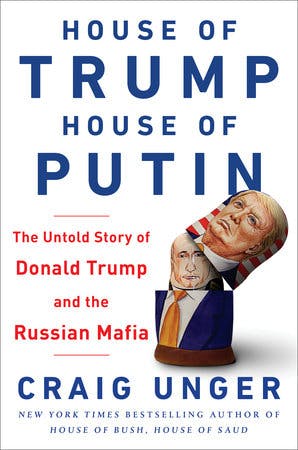

HOUSE OF TRUMP, HOUSE OF PUTIN by Craig UngerDutton, 368 pp., $30.00

HOUSE OF TRUMP, HOUSE OF PUTIN by Craig UngerDutton, 368 pp., $30.00Kalugin is of special interest these days because his experience as head of counterintelligence for the KGB makes him a master of the tradecraft that was used to ensnare Donald Trump. The operation began during a 1978 trip to Czechoslovakia not long after Trump’s marriage to Ivana, in which the newlyweds piqued the interest of the Czech Ministry of State Security (also known as the StB) enough that a secret police collaborator began observing Ivana and met several times with her in later years.

Keeping tabs on Czechs who had left the country was standard operating procedure for the StB. “The State Security was constantly watching [Czechoslovak citizens living abroad],” said Libor Svoboda, a historian from the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague. “They were coming here, so they used agents to follow them. They wanted to know who they were meeting, what they talked about. It was a sort of paranoia. They were afraid that these people could work for foreign intelligence agencies. They used the same approach toward their relatives as well.”

According to the German newspaper Bild, starting in 1979, encrypted StB files say, “the phone calls between Ivana and her father were to be wiretapped at least once per year. Their mail exchange was monitored.” The agent who reported on Ivana used the code names of “Langr” and “Chod.” The StB files are stamped “top secret,” bear the code names “Slusovice,” “America,” and “Capital,” and indicate an ongoing attempt to gather as much information about Trump as possible.

“The StB thought there was a chance that the U.S. intelligence agencies could use (Ivana Trump). And also they wanted to use Trump to gather information on U.S. high society,” said Svoboda.

The StB archives also show that Ivana’s father, Miloš Zelníček, was monitored by the secret services and that during his 1977 trip to the U.S. for Ivana’s wedding, Zelníček was subject to an StB-ordered search of his possessions at the airport. “He provided information that the secret police found out anyway from other sources,” said Petr Blažek of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, who suggested that the search was a warning shot telling Zelníček that cooperation was the only way such trips would be permitted in the future.

Far from handing over compromising materials, Zelníček may have simply delivered the minimal amount of information necessary to keep the StB off his back. “Ivana’s father was registered as a confidant of the StB,” Czech historian Tomas Vilimek told the Guardian. “However, that does not mean he was an agent. The CSSR authorities forced him to talk to them because of his journeys to the U.S. and his daughter. Otherwise, he would not have been allowed to fly.”

In the end, we do not know exactly when the KGB first opened a file on Donald Trump. But it would have been common practice for the Czech secret police to share their intelligence on the Trumps with the KGB. More to the point, Trump was so highly valued as a target that the StB later sent a spy to the U.S. to monitor his political prospects for more than a decade.

It’s unclear how much Trump himself knew about his in-laws’ encounters with Czech intelligence, but when Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, rose to power in 1985, and put forth the policies of perestroika (literally “restructuring” in Russian) and glasnost (“openness”), which eased the tensions of the Cold War, Trump became deeply infected with a severe case of Russophilia.

In the past, his participation in politics had been confined to getting his mentor Roy Cohn to push through tax abatements, changes to zoning restrictions, and the like—or making political donations to accomplish such goals. Suddenly, Trump reinvented himself as a pseudo-authority on nuclear arms and asserted that he could play a key role in strategic arms limitations.

Trump took the issue up in an interview with journalist Ron Rosenbaum in the November 1985 issue of Manhattan, Inc. magazine, in which he asserted of nuclear proliferation, “Nothing matters as much to me now”—an extraordinarily unlikely passion for a man who personified conspicuous consumption.

Trump started by telling Rosenbaum about his late uncle John Trump, an MIT professor, who explained that nuclear technology was becoming so simplified that “someday it’ll be like making a bomb in the basement of your house. And that’s a very frightening statement coming from a man who’s totally versed in it.”

What was taking place was decidedly un-Trumpian. Rosenbaum, who was anything but a Trump enthusiast, said the real estate developer “seemed genuinely aware of just how much danger nukes put the world in.” He even passed up a chance to tout the glories of Trump Tower. Instead, Rosenbaum told me, Donald Trump preferred to be seen as being in “on some serious stuff. The fact that his uncle was a nuclear scientist gave him the right to make these pronouncements.”

Trump made a similar pitch to The Washington Post. “Some people have an ability to negotiate,” he told the paper. “It’s an art you’re basically born with. You either have it or you don’t.”

Lack of confidence was not his problem. “It would take an hour-and-a-half to learn everything there is to learn about missiles,” he said. “I think I know most of it anyway.”

Which did not mean Trump was above seeking out expertise. A few months later, according to The Hollywood Reporter, in 1986, he insisted on meeting Bernard Lown, a Boston cardiologist best known for inventing the defibrillator and sharing the Nobel Peace Prize with Yevgeny Chazov, the personal physician for Mikhail Gorbachev.

Then Trump clapped his hands together, and went on to say how within one hour of meeting Gorbachev, he would end the Cold War.After accepting their Nobel medals in Oslo, Lown and Chazov went to Moscow and spent time with Gorbachev, the new Soviet leader. Not long after he returned to the United States, Lown got a message from Trump. At the time, Lown had never even heard of him but secretly hoped Trump might contribute to the Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, which was low on funds at the time.

They met in Trump’s offices on the 26th floor of Trump Tower. “I arrived totally ignorant about his motives,” Lown told me. “We sat down for lunch and Trump was very grim looking, very serious.”

“Tell me everything you know about Gorbachev,” Trump said.

After 20 minutes or so recounting his experience with the Soviet leader, however, Lown became painfully aware that Trump wasn’t listening. “I realized he had a short attention span,” Lown said. “I thought there was another agenda, perhaps, but I didn’t know what that was.”

Lown cut to the chase. “Why do you want to know?” he asked Trump.

At that, Trump revealed his grand plan. “If I know about Gorbachev, I can ask my good friend Ronnie to make me a plenipotentiary ambassador for the United States with Gorbachev.”

“Ronnie?” Lown asked.

Lown was unaware that Trump had retained the powerful lobbying firm of Black, Manafort & Stone shortly after it opened shop in 1980, and its three name partners—Charles Black, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone—had just played vital roles in Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide victory.

“Ronald Reagan,” Trump explained.

Then he clapped his hands together, Lown says, and went on to say how within one hour of meeting Gorbachev, he would end the Cold War.

“The arrogance of the man, and his ignorance about the complexities of one of the complicating issues confronting mankind! The idea that he could solve it in one hour!”

Thanks to Gorbachev, the Russian bear had finally put on a friendly face, but the KGB had not. It remained the most effective and most feared intelligence-gathering organization in the world with more than 400,000 officers inside the Soviet Union and another 200,000 border guards, not to mention an enormous network of informers. And that didn’t even include the First Chief Directorate (FCD), the relatively small but prestigious division in charge of gathering foreign intelligence. It had about 12,000 officers and was headed by General Vladimir Kryuchkov, a hard-liner who seemed to be swimming against the tides of history.

Gorbachev’s dovish overtures to the West notwithstanding, Kryuchkov, according to ex-KGB general Oleg Kalugin, was still very much “a true believer until the end, eternally suspicious of the West and capitalism.”

Kryuchkov is of special interest not simply because of his unreconstructed hard-line views. Thanks to a compendium of his memos during this period entitled “Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions: Top Secret Files on KGB Foreign Operations, 1975–1985,” we know that by 1984 he was deeply concerned that the KGB had failed to recruit enough American agents. To Kryuchkov, absolutely nothing was more important, and he ordered his officers to cultivate as assets not just the usual leftist suspects, who might have ideological sympathies with the Soviets, but also various influential people such as prominent businessmen.

And so, as if orchestrated by Kryuchkov, the political education of Donald Trump began in March 1986, when he met the Soviet Ambassador to the United Nations Yuri Dubinin and his daughter Natalia Dubinina. Dubinina, who was part of the Soviet delegation to the U.N., was an interesting figure herself in that the Soviet mission was widely known to harbor KGB agents. As she told the Russian daily Moskovsky Komsomolets, when her father arrived in New York City for his very first visit, she took him on a tour, and one of the first buildings they saw was Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue.

Natalia said her father “never saw anything like [Trump Tower], that he was so impressed that he decided he had to meet the building’s owner at once.” And so, Soviet Ambassador Yuri Dubinin and his daughter Natalia, in a highly unusual breach of protocol, went into Trump Tower, took the elevator up to Trump’s office, and paid him a visit.

It is unclear whether prior arrangements were made to set up this extremely irregular meeting between a highly placed Soviet diplomat and Trump. But a few months later, at a luncheon given by cosmetics magnate Leonard Lauder, Trump happened to be seated next to Yuri Dubinin, who proceeded to flatter the young real estate mogul shamelessly.

Trump later rhapsodized about the conversation in The Art of the Deal. “[O]ne thing led to another,” he wrote, “and now I’m talking about building a large luxury hotel across the street from the Kremlin, in partnership with the Soviet government.”

All of which sounded great, except for one thing: Everything was subject to 24-hour surveillance by the KGB.

For the KGB, Kalugin told me, recruiting a new asset “always starts with innocent conversation” like this.

As Natalia Dubinina explained, the Russians were off to an auspicious start. “Trump melted at once,” she said. “He is an emotional person, somewhat impulsive. He needs recognition. And, of course, when he gets it he likes it. My father’s visit worked on him [Trump] like honey on a bee.”

As to what Trump was really after in his quest to reinvent himself as a statesman/politician, he may have revealed part of the answer when he told The Washington Post that the man who was egging him on was none other than the mentor he so looked up to, a man for whom motives were simple. Primal. There was always money. There was always a deal. There was always an angle, and a fix.

“You know who really wants me to do this?” Trump asked rhetorically. “Roy [Cohn].”

The more Trump expanded his business and saw the spotlight, the more he sought a bigger stage. In January 1987, Trump received a letter from Ambassador Dubinin that began, “It is a pleasure for me to relay some good news from Moscow.” The letter added that Intourist, the leading Soviet tourist agency, “had expressed interest in pursuing a joint venture to construct and manage a hotel in Moscow.” Vitaly Churkin, who later became ambassador to the U.N., helped Yuri Dubinin set up Trump’s trip.

On July 4, Trump flew to Moscow with Ivana and two assistants. He checked out various potential sites for a hotel, including several near Red Square.

He stayed in a suite in the National Hotel where Vladimir Lenin and his wife had stayed in 1917. According to Viktor Suvorov, an agent for the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, “Everything is free. There are good parties with nice girls. It could be a sauna and girls and who knows what else.”

All of which sounded great, except for one thing: Everything was subject to 24-hour surveillance by the KGB.

After the trip, The New York Times reported that while Trump was in Moscow, “he met with the Soviet leader, Mikhail S. Gorbachev. The ostensible subject of their meeting was the possible development of luxury hotels in the Soviet Union by Mr. Trump. But Mr. Trump’s calls for nuclear disarmament were also well-known to the Russians.”

But in fact, Trump’s meeting with Gorbachev never really took place. The report, apparently, was merely Trumpian self-promotion. Moreover, there are many unanswered questions about exactly what transpired during Trump’s visit. It is not clear whether Trump understood that Intourist was essentially a branch of the KGB whose job was to spy on high-profile tourists visiting Moscow. “In my time [Intourist] was KGB,” said Viktor Suvorov. “They gave permission for people to visit.”

Nor is it clear if Trump was aware that Intourist routinely sent lists of prospective visitors to the first and second directorates of the KGB based on their visa applications, and that he was almost certainly being bugged.

As to what activities the KGB may have captured in its surveillance, Oleg Kalugin, as the former head of counterterrorism for the KGB, is well versed in the use of video to produce kompromat (or compromising materials), particularly of a sexual nature. At the time, it was a widespread practice for the KGB to hire young women and deploy them as prostitutes to entrap visiting politicians and businessmen, and to use Intourist to monitor foreigners in the Soviet Union and to facilitate such “honey traps.”

It was a widespread practice for the KGB to hire young women and deploy them as prostitutes to entrap visiting politicians and businessmen.“In your world, many times, you ask your young men to stand up and proudly serve their country,” Kalugin once told a reporter. “In Russia, sometimes we ask our women just to lie down.”

Which, according to Kalugin, is what probably happened during Trump’s 1987 trip to Moscow, during which he would have “had many young ladies at his disposal.”

To be clear, Kalugin did not claim to have seen such material or have evidence of its existence but was speaking as the former head of counterintelligence for the KGB, someone more than familiar with its tradecraft and practices. “I would not be surprised if the Russians have, and Trump knows about them, files on him during his trip to Russia and his involvement with meeting young ladies that were controlled [by Soviet intelligence],” he said.

On July 24, 1987, almost immediately after Trump’s return from Moscow, an article appeared in a highly unlikely venue, the Executive Intelligence Review, that strongly suggested something mysterious was going on between him and the Kremlin. “The Soviets are reportedly looking a lot more kindly on a possible presidential bid by Donald Trump, the New York builder who has amassed a fortune through real estate speculation and owns a controlling interest in the notorious, organized-crime linked Resorts International,” the article said. “Trump took an all-expenses-paid jaunt to the Soviet Union in July to discuss building the Russians some luxury hotels.”

Were the Soviets really supporting a Trump run for the presidency? Was Trump seriously considering it? Answers to the second question began to materialize less than two months after his return from Russia, when Trump turned to Roger Stone, a Nixon-era dirty trickster then with the firm of Black, Manafort & Stone, for political advice. Trump had met Stone and his colleague Paul Manafort through Roy Cohn. Although they worked in somewhat different spheres—Cohn was a hardball fixer, Stone a political strategist and lobbyist—to a large extent, they were cut from the same ethically challenged cloth.

Under Stone’s tutelage, on September 1, 1987, just seven weeks after his return from Moscow, Trump suddenly went full steam ahead promoting his newly acquired foreign policy expertise, by paying nearly $100,000 for full-page ads in The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The New York Times calling for the United States to stop spending money to defend Japan and the Persian Gulf, “an area of only marginal significance to the U.S. for its oil supplies, but one upon which Japan and others are almost totally dependent.”

The ads, which ran under the headline “There’s nothing wrong with America’s Foreign Defense Policy that a little backbone can’t cure,” marked Trump’s first foray into a foreign policy that was overtly pro-Russian in the sense that it called for the dismantling of the postwar Western alliance and was very much a precursor of the “America First” policies Trump promoted during his 2016 campaign.

“The world is laughing at America’s politicians as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help,” he wrote. “It’s time for us to end our vast deficits by making Japan and others who can afford it, pay. Our world protection is worth hundreds of billions of dollars to these countries and their stake in their protection is far greater than ours.”

Given the extraordinary success of the Western alliance as the underpinning of American foreign policy since World War II, one can only wonder who, if anyone, helped Trump come up with policies that were so favorable to the Soviets. Even more startling, an article published the next day in the Times suggested that Trump might enter the 1988 Republican presidential primaries against George H. W. Bush, then the incumbent vice president. “There is absolutely no plan [for Trump] to run for mayor, governor or United States senator,” said a Trump spokesman. “He will not comment about the presidency.”

That tease—a refusal to comment on a question that no one had asked—did not take place in a complete vacuum, however. Earlier that summer, a Republican activist named Mike Dunbar from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, had approached Trump with a proposal to speak before the Portsmouth Rotary Club, an obligatory stop for presidential candidates in the first presidential primary state. After proclaiming that Vice President George H. W. Bush, the odds-on favorite to be the GOP nominee, and Senator Bob Dole, another contender, were “duds,” Dunbar said that he raised money and collected 1,000 signatures to put Trump on the 1988 primary ballot.

But Bush had a commanding lead in the race for the Republican nomination, and Trump himself had another issue he needed to deal with. Trump had felt Ivana’s awkward English and heavy Czech accent would be liabilities on the campaign trail. It was not a happy relationship and in fact his marriage was an issue he wanted to resolve before making a serious presidential run. Nevertheless, Donald Trump’s presidential quest was under way.

Trump’s White House ambitions did not make an especially deep impression on American voters in the 1980s, but foreign agencies took notice. Several months after Trump’s visit to New Hampshire, Ivana returned to her homeland, where the Czech StB continued to keep a close eye on her. StB agents suggested Ivana was nervous throughout the trip because she believed U.S. embassy officials were following her at a time when she was supposed to be meeting with Czech security operatives. Twice, the American ambassador to Prague, Julian Martin Niemczyk, invited her to visit the embassy. But Ivana declined.

Meanwhile, the Czech secret police filed a classified report dated October 22, 1988, saying that “as a wife of D. TRUMP she receives constant attention ... and any mistake she would make could have immense consequences for him.”

In addition, the StB report made two noteworthy revelations. For the first time, it was clear that Trump had decided he would run for president. The question was timing. “Even though it [his presidential prospects] looks like a utopia,” the awkwardly translated report said, “D. TRUMP is confident he will succeed.” Only 42, the report added, Trump planned to run as an independent candidate in 1996, eight years hence.

Finally, the StB file made one more curious observation about Trump’s political future: It said he was being pressured to run for president. And exactly where was the pressure coming from? Could it have been kompromat from the honey trap in Moscow? Unfortunately, the answer was unclear.

This article was adapted from House of Trump, House of Putin by Craig Unger, published this month by Dutton. Copyright © 2018 by the author.

Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominees are often described as “battles,” but they usually turn out to be dramatic theater rather than a theater of war. Nominees are more than happy to discuss abstract legal principles or their previous rulings as judges, but they invariably decline to answer questions about how they would rule on specific cases or controversies in the future.

The two-step dance between senators and nominees is known today as the Ginsburg standard, after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, as a result of John Roberts’s confirmation hearings in 2005. His supporters argued that because Senate Democrats did not press Ginsburg after she declined to answer certain questions about her views in her 1993 hearing, he should receive a similar amount of latitude from them. Since then, senators on both sides have generally recognized this standard, even if they still try to trip up a nominee from the opposing side.

This standard is not necessarily a bad thing. It helps preserve the American tradition of judicial independence by denying senators the opportunity to extort pledges or promises in certain cases before approving a nomination. A judge who forecasts how he or she would rule in specific matters would also deprive future litigants of their right to have cases heard before a fair and impartial court.

But the Ginsburg standard also turns judicial confirmation hearings—and especially Supreme Court confirmation hearings—into a tedious, rote affair. Senators will ask a nominee’s views on subjects ranging from abortion rights to marriage equality to affirmative action. The nominee will decline to answer, citing the same reasons given by prospective justices before them. Senators will ask whether the nominee thinks cases like Roe v. Wade are still the law of the land. The nominee will give a heartfelt answer on how the American legal system values the weight of legal precedent and avoid saying how he or she would change those precedents.

Expect more of the same when Brett Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump’s pick to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy, appears before the Senate Judiciary Committee in early September. Senators will question him extensively about the cases and decisions in which he’s taken part in his twelve years of service on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Fortunately for Democrats, who will begin meeting with Kavanaugh privately on Wednesday after a weeks-long boycott, there are other ways to explore his views on major issues than to probe his time on the bench. He has an extensive record of government service predating his judicial career that is worth deeper scrutiny before handing him a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court.

With that in mind, here are some questions that Democrats could ask Kavanaugh that he might feel compelled to answer, rather than parry.

Sexual harassmentOne issue beyond Kavanaugh’s jurisprudence that senators can raise is sexual harassment in the federal judiciary. Kavanaugh once clerked for former Judge Alex Kozinski, who served in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Kozinski was one of the most influential federal judges of his era, for both his judicial writings and for his role as a “feeder”—one of the select few judges whose clerks often go on to become Supreme Court clerks. Last fall, at least 15 women came forward with accounts of sexual harassment by Kozinski, some of whom were his former clerks. He resigned from the bench in December.

Since then, Hawaii Senator Mazie Hirono has asked every judicial nominee whether they have committed sexual harassment in their careers during their confirmation hearing. Kavanaugh will almost certainly be asked the same question by Hirono. Because of his past work for Kozinski, he could also face scrutiny for what he saw during his Ninth Circuit clerkship and what he did about it. The questions could include:

When you clerked for Judge Alex Kozinski, did you witness any conduct by the judge or by any other employees for the court that could be described as sexual harassment? Did anyone ever describe incidents of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or other inappropriate behavior by him or other employees of the court to you?While working in the office of the independent counsel, in private legal practice, or in the White House, did you witness what could be described as sexual harassment or hear allegations from coworkers of inappropriate behavior from any other employees?Since joining the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, have you witnessed sexual harassment or been made aware of incidents that could be described as sexual harassment among employees of the federal judiciary?There have been debates about how best to handle sexual harassment within the federal judiciary since Kozinski stepped down. As a federal judge yourself, what steps could and should the courts take to prevent and punish it?The Clinton investigationAfter his clerkships ended, Kavanaugh spent some time in private practice before returning to government work. He spent most of the 1990s working for independent counsel Ken Starr, who oversaw the investigations into Whitewater and other Clinton administration scandals. Starr eventually concluded that Clinton had perjured himself before a federal grand jury and obstructed justice to conceal his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Kavanaugh helped Starr draft his report for Congress, which led to Clinton’s impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1998. The Senate acquitted Clinton on all charges the following year.

Democratic senators will likely take a keen interest in Kavanaugh’s work during this time period for two reasons. First, it offers a rare window into the inner workings of Starr’s investigation. Many Democrats criticized Starr at the time as a partisan effort by Republicans and conservative figures to bring down Clinton’s administration. Second, and perhaps more importantly, Kavanaugh’s work gives Democrats an opportunity to question him on issues that may resurface in the Russia investigation. That includes key questions about whether a president can be compelled to testify before a grand jury—Clinton agreed to do so in the Lewinsky saga to avoid a court battle—and whether presidents can commit obstruction of justice.

You led the three-year investigation into the suicide of Deputy White House Counsel Vince Foster. Why did your office investigate Foster’s death after multiple other inquiries had already ruled it a suicide? Why did your investigation into Foster’s suicide take three years to complete when other investigators reached the same conclusion in a far shorter time frame?In a 1995 memo to independent counsel Ken Starr, you wrote that you found arguments that a president shouldn’t be called to testify before a grand jury to be “unpersuasive.” You went on to add, “Why should the president be different from anyone else for purposes of responding to a grand jury subpoena ad testificandum?” Do you still agree with that?In a 1998 letter, you recommended to Starr that he should refrain from pursuing a criminal indictment against Clinton while he remained in office. At that time, did you believe that the independent counsel’s office could lawfully indict a sitting president?Were there debates within the Office of the Independent Counsel about whether it would be constitutional to issue a criminal indictment against a sitting president? Was there ever any discussion within the OIC on whether a president could pardon himself?At any point during your tenure did you provide non-public information to journalists who were covering the OIC’s work?The Bush White HousePerhaps the area of greatest scrutiny from Democrats will be Kavanaugh’s work in the White House under George W. Bush. From 2001 to 2003, he worked in the White House counsel’s office, which handles legal matters related to the office of the presidency itself. Kavanaugh then worked as the White House staff secretary from 2003 to 2006. The role is an important one in any White House: The staff secretary oversees the flow of papers to and from the president. Kavanaugh’s defenders have characterized the role as one akin to a “traffic cop,” while others have contended that an effective staff secretary can play a subtle but influential role in policymaking decisions.

Democrats and Republicans have clashed over Kavanaugh’s paper trail from that era since his confirmation battle began. The National Archives told senators, earlier this month, that this likely wouldn’t be available until the end of October. Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Chuck Grassley, a Republican, subsequently scheduled Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing for early September, meaning that senators won’t have access to all of the requested documents before they question him in three weeks. Grassley also rejected Democrats’ bid to seek Kavanaugh’s records from his time as staff secretary, which amounts to more than a million pages. Republicans have dismissed those efforts as frivolous, while Democrats have suggested that Republicans are trying to hide something.

In their questions for Kavanaugh, senators will likely ask questions about the thousands of pages that have already been released. They may also ask more broadly about the role Kavanaugh played in some of the Bush administration’s most controversial policies, including Guantanamo Bay detainees, warrantless surveillance programs, and torture.

In a White House email dated March 15, 2001, you told colleagues that you would recuse yourself from three areas of legal matters while working in the White House counsel’s office: matters related to lawsuits brought by the legal organization Judicial Watch, matters related to the grand jury investigation of Bill Clinton, and matters involving the cosmetics industry. Do you intend to recuse yourself in those matters while serving on the Supreme Court? If not, why not?In 2015, you served on a three-judge panel in the D.C. Circuit that ruled in favor of a lawsuit brought by Judicial Watch. Why did you recuse yourself from cases involving the organization when you served in the White House, but not while on the D.C. Circuit?The March 15 email appeared to reference “additional matters/issues” on which you had recused yourself. Is this accurate, and if so, from what other issues did you recuse yourself while working in the White House counsel’s office? If you are confirmed, would you recuse yourself from those issues while serving on the Supreme Court?What role did you play, if any, in crafting the Bush administration’s policy on Guantanamo Bay and other detainees?During your confirmation hearing in 2006, you told the Senate Judiciary Committee that you were “not aware” of issues relating to detainee policy while working in the White House counsel’s office in 2003. In 2007, news reports indicated that you took part in discussions among White House staffers on how the Supreme Court would rule on detainee issues. Do you consider your answer in 2006 to be misleading?What role did you play, if any, in crafting the Bush administration’s policy on torture, which were often described as “enhanced interrogation techniques”?How would you define “torture”? Do you consider waterboarding to be torture?What role did you play, if any, in crafting the Bush administration’s policy on warrantless surveillance programs?What role did you play, if any, in crafting the Bush administration’s rationale for the Iraq War?Were you aware that White House staffers were using a private email server operated by the Republican National Committee to conduct official business, as publicly revealed in 2007? What steps did you take, if any, to notify those staffers of their obligations to preserve government records under the Presidential Records Act?Presidential powerKavanaugh has already drawn extensive scrutiny for his writings and remarks over the past 20 years. It’s not uncommon for Supreme Court nominees to face questions about this type of work: Neil Gorsuch, for example, fielded numerous questions last year about a 2006 bioethics book he had written from senators who hoped to glean some insight into his views on abortion rights. For Kavanaugh, the issue is executive power. I noted last month that some of his writings and comments point toward an extraordinary degree of deference to the executive branch and its whims. With Donald Trump in the White House and special counsel Robert Mueller investigating him, Kavanaugh’s views of the presidency’s powers have taken on an even greater significance.

In 2016, you told an audience at the American Enterprise Institute that you would like to overrule the Supreme Court’s 1986 decision in Morrison v. Olson, which upheld the constitutionality of the Independent Counsel Act. “It’s been effectively overruled, but I would put the final nail in,” you said at the time. Do you still believe that Morrison v. Olson should be overturned?In 1999, you said during a panel discussion that the “tensions of the time may have led to an erroneous decision” in United States v. Nixon, which is more widely known as the Watergate tapes case. Do you still agree with that position today? If not, why not?There are multiple definitions for what constitutes a constitutional crisis. How do you define the phrase?Do you think Nixon’s actions during the Watergate scandal, including his decision to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox in the Saturday Night Massacre, amounted to a constitutional crisis?Since the Watergate scandal, the Justice Department and the FBI have operated with a measure of independence from the presidency. Do you think this is appropriate?In a 2009 article for the Minnesota Law Review, you argued that Congress should immunize presidents from civil lawsuits and criminal indictments during their tenure in office. Do you still agree with that position today?Do you believe it is appropriate for presidents to publicly disparage individual judges for issuing rulings with which they disagree?Donald TrumpTo that end, senators will also spend time questioning Kavanaugh about the process by which he became a nominee for the Supreme Court. Trump is known for making ethically dubious requests in private conversations with government officials, and Democrats will want Kavanaugh’s assurances under oath that nothing amiss took place when the White House weighed him for the post. Democrats may also try to pry into the Trump White House’s work with conservative legal groups to select a Supreme Court nominee, including work by Leonard Leo, the Federalist Society executive vice president who played an influential role in the shaping the Supreme Court’s current membership.

Did the president or anyone else involved in your nomination process ever ask you about the Russia investigation? What about the Michael Cohen investigation, the criminal trial of Paul Manafort, or any other federal or state criminal investigation, past or present?When did you learn that the Trump administration was considering you for a vacancy on the Supreme Court?In your Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire for this nomination process, you listed yourself as a member of the Federalist Society from 1988 to the present day. In an email dated March 18, 2001, you told other members of the White House counsel’s office that you resigned from that organization “before starting work here.” Which account is accurate?Did you have any formal or informal discussions with Leonard Leo, other members of the Federalist Society, or members of the Heritage Foundation about your potential nomination to the Supreme Court before it was made public?

If recent history is any guide, Kavanaugh’s hearings will stretch on for three or four days and, despite Democrats’ designs to the contrary, he will be confirmed. The senators can spend that time engaging in a predictable back-and-forth with him about hypothetical scenarios involving major precedents, or they can grill him with concrete questions about his professional past that he won’t be able to evade so easily. The public would be much better served by the latter.

American culture is in love with murder. It has always been this way: People like watching killers cavort in the movies, and trashy true-crime documentaries pull in the numbers. There’s a whole network called Crime & Investigation. But our obsession with murder took a new turn with 2014’s Serial, which elevated the practice of turning a real murder—a real death—into a form of entertainment. It let middle-to-high-brow consumers feel better about their voyeurism. If they were interested in the narrative problems of the crime, the listener was no longer obsessing over lurid violence; they were considering the relation between truth, language, and reality. Or something like that.

A new TV show called I Am A Killer pushes the genre to the absolute limit of acceptability—then goes right across it, arriving at the gruesome apotheosis of our obsession with killers and killing. The show (produced by Sky Vision and distributed by Netflix) is a documentary series that interviews a different man on death row in each episode. The show represents the crossing of a cultural rubicon, the transformation of something abnormal into ordinary entertainment.

I Am A Killer dresses the murders in a cloak of unreliable narrative. In each episode we first see the convicted man speak directly to the camera. In episode four, Miguel Angel Martinez of Laredo, Texas, describes how, at the age of 17, he entered the home of James Smiley, a man he had previously lived with. Martinez brought two friends, Manuel “Milo” Flores (also 17) and Miguel Angel Venegas, Jr. (16). Martinez and Venegas killed everybody in there and Flores brought along the weapons. On the way out Venegas turned a crucifix by Smiley’s bed upside down.

Martinez is the focus, at first. He has charismatic eyes, in that they’re sort of sexy and frightening at the same time. He explains that he intended to only rob the place with his friends, but things just turned. After Martinez’s interview, we then meet various other characters. We meet people who knew Smiley, who mourn his death. We also meet Venegas, who says that when he was 8 years old he “became convinced that [he] was the son of the devil.” To prove this to himself Venegas would fill up a jar with black widow spiders and then pour them on his chest. If he was the son of the devil they wouldn’t bite him. They never did.

All the episodes follow this narrative course. The producers then play for the killer various tapes and interviews they have gathered in the interim. In the case of Martinez, the producers have discovered that James Smiley, with whom Martinez lived as a child, was known to have been a pedophile. This information was deliberately withheld from the early section of the episode, so that the story would have a twist. They play Martinez a tape of Flores’s father explaining that the kids went after a man who seemed like a “good man” but was actually a “bad man.” Martinez loses his composure and seems near tears, but does not explain further. At the end of the episode a title card tells us that Martinez’s death sentence has since been commuted to life in prison—the courts found that a jury has to have been unanimous in passing such a sentence, and his wasn’t.

It’s an unsatisfying conclusion, and in general the show delivers the profound sense of having short-changed all its subjects, from the murderers to the victims. Abuse, murder, capital punishment: Aren’t these the kind of plot points that merit full-length novels, or entire television seasons? That I Am A Killer crams each of these extremely complex crimes into one episode, then moves onto the next, feels like brutalization-by-television, a punishment on top of a punishment.

If there’s an artistic justification for this show, it lies in the old question of unreliable narrators. Inevitably, the murderer’s initial story ends up questioned by other people. Often, the discrepancies are never solved, not even in court. The conviction reflects the dominant narrative, the one the jurors believed the most. I Am A Killer has the interesting side effect of proving that the law’s “version of events” is always just a story. Narrative is what constitutes crime and punishment.

There are also a lot of parallels between the different cases. Often the murderer has been abused as a child, or describes going on a downward spiral after their father dies. Often the murderer makes very piercing eye contact with the camera, even the ones who are being interviewed through glass. People close to the crime very often describe having a “bad feeling” about the day in question, even if there’s no way they could have known what was about to happen. The convicted men often refer to their “case” as if it were something they found themselves in, rather than a crime they committed.

Ultimately, the show’s most compelling moments are the absurd ones. In episode one, for example, we meet James Robertson, a man jailed for a more minor crime who eventually murdered his cellmate in order to get housed on death row (he says the conditions are better there). The Florida Department of Corrections gave him his wish. Later, we meet his lawyer, who likes to spend his spare time driving around on a boat called The Defense Rests.

Still, this kind of television is not normal, for want of a better term. There are good reasons for depriving convicted murderers of screen time. In the case of a Texan named Charles Thompson, for example, we meet the foreman of the jury who sentenced him to death. “He’s narcissistic, he enjoys the attention,” she says. These men will glory in their brief moment of celebrity. They’re all lit well, and allowed to deliver their own version of events, in their own words. Is this how justice is supposed to work, with TV supplementing the courts in the battle for a criminal’s reputation?

In this, I Am A Killer struggles to justify its own existence. Convictions are made of narrative, true, and there is always “more than one side to the story.” Broadcasting the soon-to-be-gone stories of soon-to-be-dead men, however, is cruel and unusual business.

“They spit when I walked in the street,” Joanna Galilli, 28, a French Jew, told the New York Times late last month. She, like many Jews in recent years, had left a suburb of Paris to move to the 17th arrondissement, a district in the city’s western corner with a growing Jewish population. She lamented a “new anti-Semitism”—one that emanates not from the far right but from Muslims.

France is home to Europe’s largest Muslim and Jewish populations, and tension between the two communities isn’t new. But it has gained urgency since March, when Mireille Knoll, an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, was stabbed to death in her Paris apartment by her 28-year-old neighbor, Yacine Mihoub. A 21-year-old homeless man, who was with Mihoub at the crime scene, alleged that he had cried “Allahu Akbar!” as he stabbed Knoll. The grisly act drew up memories of the murder, just a year prior, of 67-year-old Sarah Halimi, a Jewish woman who was beaten to death, also by her neighbor—and in the same area of Paris—who proceeded to throw her body off her third-story balcony while also yelling “Allahu Akbar!” It took the judicial authorities ten months, and significant public pressure, to acknowledge that Halimi’s murder was an anti-Semitic crime.

Knoll’s murder, in contrast, was swiftly labeled as such. Thousands marched across France days after her death to condemn anti-Semitism. A month later, some 300 high-profile public figures, intellectuals and elected officials—past and present, across the political spectrum—signed a controversial manifesto published in French daily Le Parisien denouncing a “new anti-Semitism” perpetuated by Muslims, and lambasted what they called the media’s silence on the issue. Persistent attacks, from vandalism to physical aggressions, have led Jewish families to pull their children out of public schools and change neighborhoods, a trend the authors of the manifesto likened to a “low-volume ethnic cleansing.” French elites, they contended, particularly on the left, use “anti-Zionism as an excuse,” portraying “Jews’ executioners as society’s victims,” all because “crude electoral math suggests the Muslim vote is ten times superior to the Jewish vote.”

French Jews, who are the country’s most-accepted minority—Roma and Muslims are the least—do not face “low-level ethnic cleansing,” and the media has hardly been silent about anti-Semitic violence. But anti-Jewish sentiment is high. Although 89 percent of French people see Jews as “French like the rest,” 35 percent say they “have a particular rapport with money,” 22 percent believe they have “too much power,” and 40 percent believe that “for French Jews, Israel counts more than France.” And while the Interior Ministry logged fewer anti-Jewish crimes in 2017 than in 2016, those that did occur were more violent in nature. Despite constituting roughly one percent of the population, Jews were the victims of more than a third of hate crimes in 2017.

France has been slow to reckon with its history of anti-Semitism. It wasn’t until 1995 that then-President Jacques Chirac admitted the Vichy government’s “inescapable guilt” in collaborating with the Nazi regime’s atrocities, and only in 2009 did judicial authorities formally recognize France’s role in deporting thousands of Jews during World War II. Late last year, a debate raged over whether to republish the works of the late novelist and pamphleteer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose works are laden with anti-Semitism. And in January, a controversy erupted when Charles Maurras, a virulent anti-Semite who was an active proponent of Vichy-era nationalism, was included in an annual initiative to mark the anniversaries of significant figures and events. The recently renamed far-right National Rally party—formerly the National Front, whose founder and former president Jean-Marie Le Pen, a notorious anti-Semite, called the gas chambers a “detail of history”—won an unprecedented 34 percent of votes in the 2017 election.

It’s also true that since the early 2000s, French Muslims have often been behind anti-Semitic violence, from Mohamed Merah, who opened fire at a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012, killing a teacher and four students, to Amédy Coulibaly, who took hostages and killed four at a kosher supermarket in eastern Paris in 2015, to name but two examples. That worrying trend coincides with an era of rising terrorism on French soil, in many cases perpetuated by nationals claiming to defend a radical interpretation of Islam. This climate, which has stoked general suspicion of Muslims, has bolstered the narrative that contemporary anti-Semitism is an exclusively Muslim phenomenon.

Yet the Muslim perpetrators of anti-Jewish violence tend to invoke the same old tropes about money and power that are widespread among the French population at large. “Anti-Semitism hasn’t changed, it’s alive and well,” Johanna Barasz, a spokesperson for the Dilcrah, a government organization that coordinates efforts to combat racism, anti-Semitism and homophobia, told me. “It’s a bit surprising to, on the one hand, see uproar about a ‘new’ anti-Semitism, and on the other, consider it completely fine to republish Céline’s texts,” she went on, describing a “living room anti-Semitism” that not only remains vibrant but “ideologically feeds anti-Semitism among Muslims.”

Violence between French Muslims and Jews has also routinely corresponded to upticks in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The notion of a “new anti-Semitism,” then, overlooks both anti-Semitism’s endurance in France—including among non-Muslims—and the way more than a half-century of Jewish-Muslim hostility in the Middle East has played into this trend.

“Especially since the Six-Day War [in 1967], we’ve seen an anti-Jewish vision based on the demonization of Israel and of Zionism,” Pierre-André Taguieff, a director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research, told me in an interview. He attributes that shift to then-President Charles de Gaulle’s denunciation of Israel’s entry into that war, which was fought against Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

That reading hinges on the notion that there is an equivalency, or at least causality, between criticism of Israel and anti-Semitism. And while some of Israel’s detractors are undeniably galvanized by their hatred of Jews, that is hardly true across the board. Yet in recent years, France’s official positions have helped to conflate the two. The global Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement to get Israel to withdraw from occupied territories, for example, has been illegal in France since 2015 on the grounds that it provokes “discrimination, hatred or violence against a person or group for their religion or belonging to an ethnicity, nation, race or religion.” In a meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last summer, French President Emmanuel Macron called anti-Zionism a “reinvented” form of anti-Semitism. That has fueled the confused perception that Jews, by virtue of their religion, are unconditionally tied to Israel and its politics—and accordingly, that they are a legitimate target for anti-Israel sentiment.

For Taguieff, this in part reflects the increasingly religious undertones of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—what he calls an “Islamization of the Palestinian cause,” in which the Islamist Hamas party, which has controlled Gaza since 2006, has deemed “Palestine a Muslim territory,” and, accordingly, transformed opposition to the occupation into a religious rallying point for Muslims across the world. And as Hamas has indeed fused religious zeal into the Palestinian cause, Israel’s leaders, in the throes of an unprecedented rightward shift that has given new credence to religious figures, have adopted a similar strategy. A new law, which declares Israel the “nation-state of the Jewish people” and enshrines the right of national self-determination as “unique to the Jewish people”—rather than to all citizens—exemplifies this shift. Netanyahu’s right-wing nationalism often seems to trump his concern for anti-Semitism in Europe; in April, the Israeli prime minister congratulated Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister who has pursued an anti-Semitic, defamatory campaign against philanthropist George Soros, on his re-election.

The task, then, is not to discount the pressing reality of anti-Semitism in France, but to identify its nuanced sources—from its footing in French society at large to the influence of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “It’s clear that something needs to be done,” Barasz said, “but blaming French Muslims for anti-Semitism just fuels the fire. If we leave the debate to the hysterics, to the radicals, we’ll miss our opportunity.”

No comments :

Post a Comment