Brett Kavanaugh’s opening statement before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday was unlike anything in the Supreme Court’s history. In what can only be described as an angry and vengeful tirade, he lashed out at the American left, Democratic lawmakers, and “friends of the Clintons” for the attacks and allegations that he’s faced since his nomination to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy. It was an astonishingly partisan performance for a sitting federal judge, let alone one who hopes to serve on the nation’s highest court.

“This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record, revenge on behalf of the Clintons, and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups,” he told senators. “This is a circus.”

Kavanaugh then suggested that there would be dire consequences for those groups at some point in the future. “This grotesque and coordinated character assassination will dissuade competent and good people of all political persuasions from serving our country,” Kavanaugh said. “And as we all know, in the United States political system of the early 2000s, what goes around comes around.” After that assertion, imagine being a Democratic official or liberal interest group who brings a case before the court and loses it in a 5-4 decision with Kavanaugh in the majority.

This statement cannot be squared with what Kavanaugh said during his opening statement to the senators just weeks ago. “The Supreme Court must never be viewed as a partisan institution,” he said. “The justices on the Supreme Court do not sit on opposite sides of an aisle. They do not caucus in separate rooms. If confirmed to the court, I would be part of a team of nine, committed to deciding cases according to the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

It’s worth noting that Kavanaugh is not just a Supreme Court nominee. He’s currently a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, and if the Senate decides to reject his nomination, he’ll remain there. Kavanaugh is therefore required to abide by the code of conduct for federal judges, even outside the courtroom. “A judge should be faithful to, and maintain professional competence in, the law and should not be swayed by partisan interests, public clamor, or fear of criticism,” the code states.

Two women have publicly alleged that Kavanaugh sexually assaulted them in high school and in college, respectively. A third woman has said Kavanaugh was present at a beach party in Maryland in high school where she was gang-raped, though she does not allege that he took part in the attack. Kavanaugh has denied all wrongdoing, and he’s certainly entitled to defend himself. But he went far beyond that and cast the allegations, without evidence, as part of a grand conspiracy against him.

Kavanaugh undermined his credibility as a fair-minded jurist by indulging in some imaginative leaps to attack Democratic senators. “The behavior of several Democratic members of the committee in my hearing a few weeks ago was an embarrassment,” he said. “But at least it was just a good old-fashioned attempt at borking. Those efforts didn’t work. When I did at least okay enough at the hearings that it looked like I might actually get confirmed, a new tactic was needed. Some of you were lying in wait and had it ready. This first allegation was held in secret for weeks by a Democratic member of this committee and this staff. It would be needed only if you couldn’t take me out in the merits.”

He was referring to California Senator Dianne Feinstein, who learned about Christine Blasey Ford’s allegation in a letter from her during the summer. Blasey testified that she declined to take the allegations public when Kavanaugh’s confirmation appeared certain. Feinstein pledged she would keep them confidential. Nonetheless, rumors about Blasey’s letter began to surface after Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing. (He did not blame Blasey, saying the letter was released “over Dr. Ford’s wishes.”) The Intercept was the first news outlet to report on the letter’s existence. After Kavanaugh’s testimony, D.C. bureau chief Ryan Grim said on Twitter that the letter wasn’t leaked to them by Feinstein’s staff.

In 1991, Clarence Thomas gave a similarly defiant opening statement to the committee. He described the firestorm surrounding Anita Hill’s allegations that he sexually harassed her as “Kafkaesque” and a “grave and irreparable injustice” to him and his family. “No job is worth what I’ve been through—no job. No horror in my life has been so debilitating,” he told senators, adding that “from my standpoint as a black American, as far as I’m concerned, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate, rather than hung from a tree.”

Thomas’s words, as vivid and severe as they were, did not constitute an overtly partisan attack—much as he may have wanted to do so. He came pretty close in an autobiography he released in 2007, where he broadly alleged that liberal groups had weaponized Hill’s allegations because of Thomas’s perceived views on abortion. But he managed to show at least a measure of restraint at the time. Kavanaugh, by comparison, did not. His behavior on Thursday casts serious doubt on whether he has the temperament to sit on the Supreme Court.

Republicans who support Kavanaugh’s nomination frequently touted his twelve years of service on the D.C. Circuit. But Democrats focused on his years as a political operative for the Republican Party and the conservative movement—first as one of the inquisitors on Ken Starr’s Whitewater investigation into the Clinton White House, then as a Bush White House staffer for five years. They worried that he would continue that work if placed on the Supreme Court. Kavanaugh seemed to validate that fear in the most visceral way possible on Thursday.

Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination is taking on water with every passing moment. Two women have accused him of sexually assaulting them in the early 1980s, while a third says she witnessed him groping women without their consent at house parties. (He denies any allegations of wrongdoing, calling them “last-minute smears, pure and simple.”) There are rumblings that a growing number of Republican senators are uneasy about supporting him, though others are signaling confidence. “I’ll listen to the lady, but we’re going to bring this to a close,” South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham recently said. On Wednesday, after the third accuser’s allegations surfaced, Utah’s Orrin Hatch said, “I don’t think we should put up with it, to be honest with you.”

Republicans more broadly appear to be standing by Kavanaugh even as the rest of the country moves away from him. An NPR/PBS/Marist poll released on Wednesday found that, whereas 59 percent of all Americans think he shouldn’t be confirmed if Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations are true, 54 percent of Republicans think he should be confirmed even if the allegations are true.

What drives the right’s insistence on elevating Kavanaugh to the nation’s highest court? Blasey’s testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday could imperil a four-decade effort by American conservatives to bring a majority of the Supreme Court in line with their ideological views. Justice Anthony Kennedy’s retirement earlier this year gave the influential alliance of legal organizations, think tanks, and donors a long-awaited chance to finish the task, and it’s unclear whether anything, even credible accusations of sexual assault, will stop them now.

The conservative legal movement, like American conservatism as a whole, is not monolithic. It includes big businesses that are hostile to organized labor, social conservatives who resent the secularization of public schools and loathe abortion, libertarian-minded skeptics of federal regulations and social programs, Southern whites who opposed desegregation and civil-rights laws, and law-and-order types alarmed by the expansion of criminal defendants’ rights and protections in the 1960s. What united them was an aversion to the status quo and the Supreme Court that enshrined it.

Presidents always have used Supreme Court nominations for political and electoral purposes, and Dwight D. Eisenhower was no different. He nominated Earl Warren, California’s popular Republican governor and a key supporter in the 1952 Republican primaries, to be chief justice the following year. He later tapped William Brennan to a vacant spot in 1956 to appeal to Catholics in the Northeast during that year’s election. The two men became the nucleus of what is generally referred to as the Warren Court, which spanned from the mid-1950s until Warren retired in 1969. It was the most progressive era in the court’s history, but its victories brought a backlash from more conservative elements.

Richard Nixon capitalized on that backlash in the 1968 election, pledging to appoint what he called “strict constructionists”—a term no longer used to describe conservative jurists—who would interpret the Constitution as it was written. To that end, he nominated Warren Burger as chief justice and three associate justices during his presidency: Lewis Powell, Harry Blackmun, and William Rehnquist. Rehnquist would ultimately be the only one who satisfied conservatives. Blackmun committed the ultimate heresy by authoring Roe v. Wade, for example, which Burger and Powell both joined. The Warren Court’s landmark precedents went no further, but neither were they rolled back.

The Reagan years were a crucible for the conservative legal movement. Scalia, who served as a faculty adviser to the Federalist Society when it was founded in 1982, joined the court in 1986. In 1985, Attorney General Edwin Meese called for a “jurisprudence of original intent,” where judges interpret the founding document as its drafters intended, to counter the court’s perceived liberalism. Two years later, Powell announced that he would retire from the court. To replace him, Reagan first tapped Robert Bork, a prominent federal judge and legal scholar. Bork was a rock star of sorts within the conservative legal movement and well-known beyond it for his landmark text on antitrust law. Everyone expected that his presence on the high court would greatly accelerate its drift towards the right.

Democrats and liberal interest groups immediately rose up in revolt against his nomination. Bork had been the executioner of the Saturday Night Massacre by following Nixon’s order to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox. His oft-expressed views on constitutional matters like abortion, civil rights, and privacy came under intense scrutiny and criticism as well. “Robert Bork’s America,” declared Ted Kennedy on the Senate floor, “is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids,” and more. After a poor performance in his confirmation hearings, senators quashed Bork’s nomination in a contentious 42-58 vote.

The Senate’s rejection of Bork incenses American conservatives to this day. They often single out Kennedy’s floor speech as unfair at best and slanderous at worst, but also blame the Reagan White House for not rising to his defense. “Instead the Republican master strategists let themselves be trapped in absurd debates about whether, under Emperor Bork, you would be able to buy condoms in Connecticut,” National Review’s editors fumed after the vote. “The Republican National Committee is suffocating in cash. Why didn’t the Republicans match the Left? Answer: because they are inert, and lacking in intelligent direction.”

The lesson was threefold. Potential Supreme Court nominees must be vigorously defended when attacked by liberal groups, not left to fend for themselves. They should lack a long and inflammatory paper trail like Bork’s to minimize those attacks. And the growing campaign to remake the courts can’t be limited to the presidency; the Democratic stranglehold on the Senate would have to be broken, too. “There are other good Supreme Court possibilities,” National Review’s editors mused. “But it’s not morning in America, baby. It’s hard-ball time.”

The early 1990s also exposed the conservative legal movement’s limits. When William Brennan, a liberal icon and one of the Warren Court’s last survivors, stepped down in 1990, Bush nominated the mild-mannered David Souter to replace him. Souter was not part of the movement, but the White House assured conservatives he sympathized with it. Instead, he became one of the most reliable members of the court’s liberal wing. Another lesson: Nominees must have enough of a paper trail to ensure they aren’t another Souter, but not so much of a trail that they become another Bork.

Bush then nominated Clarence Thomas, a newcomer to the federal bench who had impeccable conservative credentials, to replace Thurgood Marshall in 1991. This time, the Marshall-to-Thomas shift was one of the largest ideological swings for a Supreme Court seat in the twentieth century.

Then came Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 case that squarely asked whether Roe v. Wade should be overturned. Democrats and the American left feared that it would, after four of the court’s justices had already signaled their willingness to overturn it. Conservatives saw their long-awaited victory at hand. The decision surprised both sides: a 5-4 ruling that not only declined to overturn Roe, but reaffirmed its constitutionality. Three Republican appointees—Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and David Souter—jointly wrote the majority opinion laying out the undue-burden standard to determine when abortion restrictions went too far.

The final lesson was perhaps the most important one of all: It’s not enough to place justices on the court who were largely conservative, somewhat conservative, or simply not liberal. They must be reliably conservative. What-ifs haunt the conservative legal movement. Between Thurgood Marshall in 1968 and Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993, no Democratic president had named a new justice. Republicans had an incredible run of eleven consecutive justices, and they still couldn’t build a five-justice majority to accomplish what their base demanded. Had Bork taken the seat that went to Kennedy, Roe would have been obliterated. If Bush had nominated a more reliable conservative than Souter, it would have perished no matter what O’Connor or Kennedy did.

This is how conservatives see the modern history of the Supreme Court: as a long chain of near-victories and half-defeats that only galvanized them further. The American left, meanwhile, saw a high court that was generally conservative but not that conservative. Women could still have abortions, even though states were now free to impose new restrictions on them. Laws like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 lost some of their bite, but remained on the books. And if it looked like something seismic was about to happen, there was nothing to truly fear—O’Connor or Kennedy would save the day.

The conservative legal movement played an influential role in the judicial battles of the George W. Bush years, but they didn’t truly flex their muscle until 2005. That July, Sandra Day O’Connor announced that she would retire from the court. Her departure gave Republicans their long-awaited chance to replace a swing vote with a solidly conservative one. With a Republican president and a Republican-led Senate, there would be no borking this time. “On October 23, 1987—a day that lives in conservative infamy—Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court was rejected by a Democratic Senate,” The Weekly Standard’s Bill Kristol wrote after O’Connor’s announcement. “Now, 18 years later, George W. Bush has the chance to reverse this defeat, and to begin to fulfill what has always been one of the core themes of modern American conservatism: the relinking of constitutional law and constitutional jurisprudence to the Constitution.”

Bush responded by nominating John Roberts, whom he had elevated to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals two years earlier. Roberts had all the necessary qualifications: He was only 50 years old at the time, an excellent legal writer who hadn’t drafted any disqualifying opinions, and a familiar face at Federalist Society debates and lectures. In the liberal imagination, the Federalist Society is a gothic laboratory of sorts where Republican power-brokers grow originalist judges in cloning vats beneath their D.C. headquarters. The reality is much more mundane. Roberts wasn’t a member, but conservatives knew him well enough to not fear that he was a Souter.

When Rehnquist died that summer, Bush re-nominated Roberts to be chief justice instead. Then, to replace O’Connor for the crucial swing seat, he turned to Harriet Miers, a longtime aide and ally. This time, it was conservatives who revolted against a Supreme Court nominee. She was not part of the movement that they spent years building. She wasn’t credentialed by its institutions. She could endanger the whole enterprise.

“He has put up an unknown and undistinguished figure for an opening that conservatives worked for a generation to see filled with a jurist of high distinction,” Kristol wrote. “There is a gaping disproportion between the stakes associated with this vacancy and the stature of the person nominated to fill it.” Miers eventually bowed out amid conservative pressure, and Bush nominated Samuel Alito in her stead, to the movement’s applause. Kennedy was the last swing justice standing.

If Republicans get Kavanaugh on the high court, the American left likely will be thrust into the constitutional wilderness for at least a generation. At the moment, the machinery to claw back control of it is in its infancy. A group of Obama and Clinton veterans recently founded Demand Justice, a nonprofit organization in D.C. that aims to make the judiciary a core progressive issue. Demand Justice played a vocal role in the Kavanaugh saga and will likely be a key player in future confirmation fights, especially if Democrats retake the Senate this fall. Other essential components are further behind. American liberals lack an institution with the credentialing heft of the Federalist Society, or think tanks with judicial policy experience as deep as the Heritage Foundation. It’s also uncertain if there is a donor network willing to bankroll a judicial advocacy movement on the left.

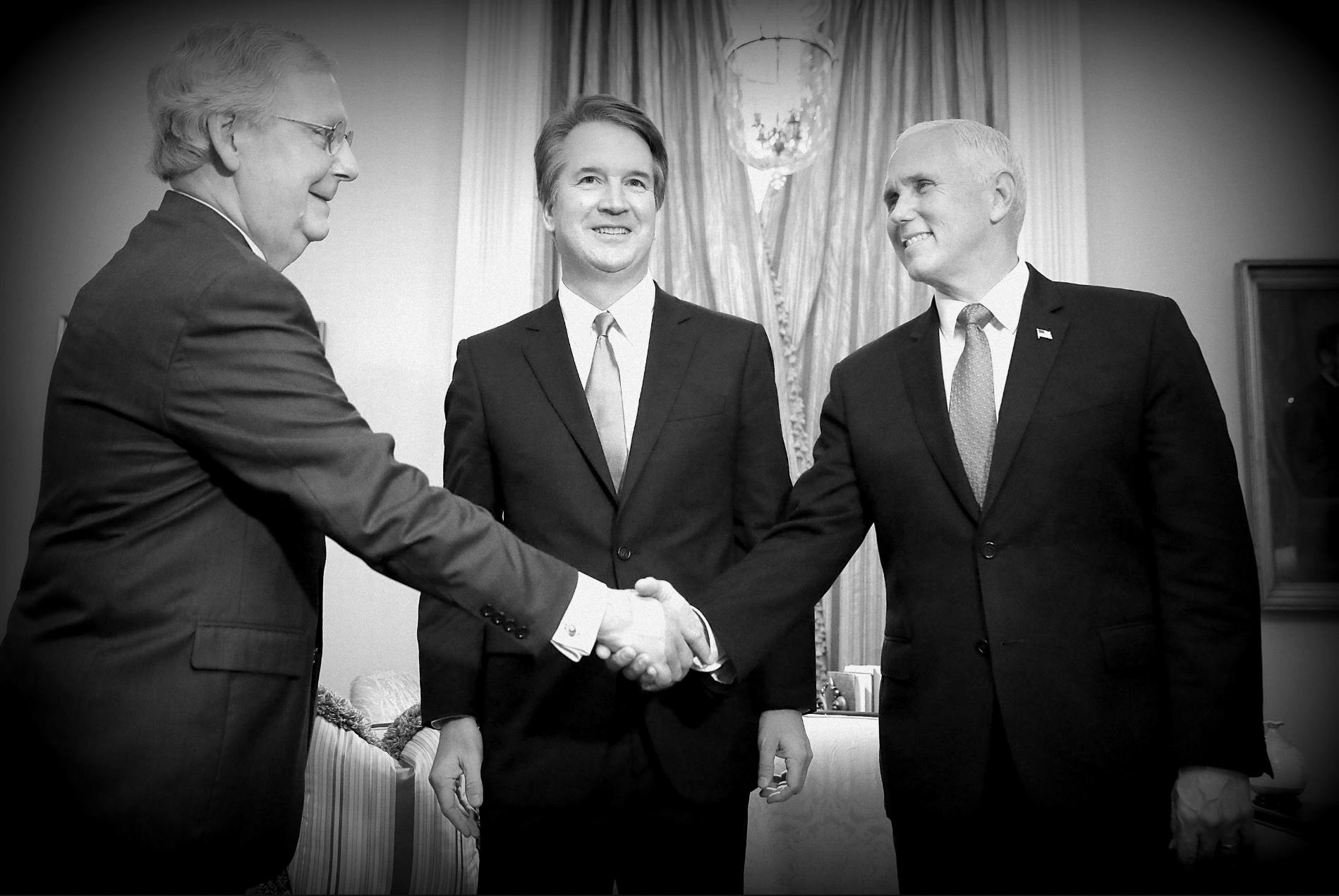

What liberals do have is the founding mythology that can fuel that movement. In 2016, President Barack Obama nominated Merrick Garland, an affable centrist judge on the D.C. Circuit, to replace Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made the unprecedented decision to refuse to hold hearings or a vote, insisting that it wait until after the presidential election. “The next justice could fundamentally alter the direction of the Supreme Court and have a profound impact on our country, so of course the American people should have a say in the court’s direction,” he said.

But McConnell surely wasn’t motivated by democratic concerns. He saw that conservatives’ decades-long dream was imperiled—that the court would shift decisively left for perhaps a generation. That’s why some Republicans vowed, even before the election, to block any nomination put forth by Hillary Clinton if she won. The question became moot, but if anything, Donald Trump’s victory made the Garland episode an even more galvanizing moment for Democrats—one they may use to justify almost any step necessary to retake the courts.

Thirty-one years ago, conservatives described the Bork nomination as “hard-ball time.” Now it’s liberals’ turn.

No comments :

Post a Comment