In July, Jeff Merkley, the junior senator from Oregon, traveled to Iowa. The trip was his third in twelve months—a sign, political commentators said, that he was preparing to launch a presidential bid.

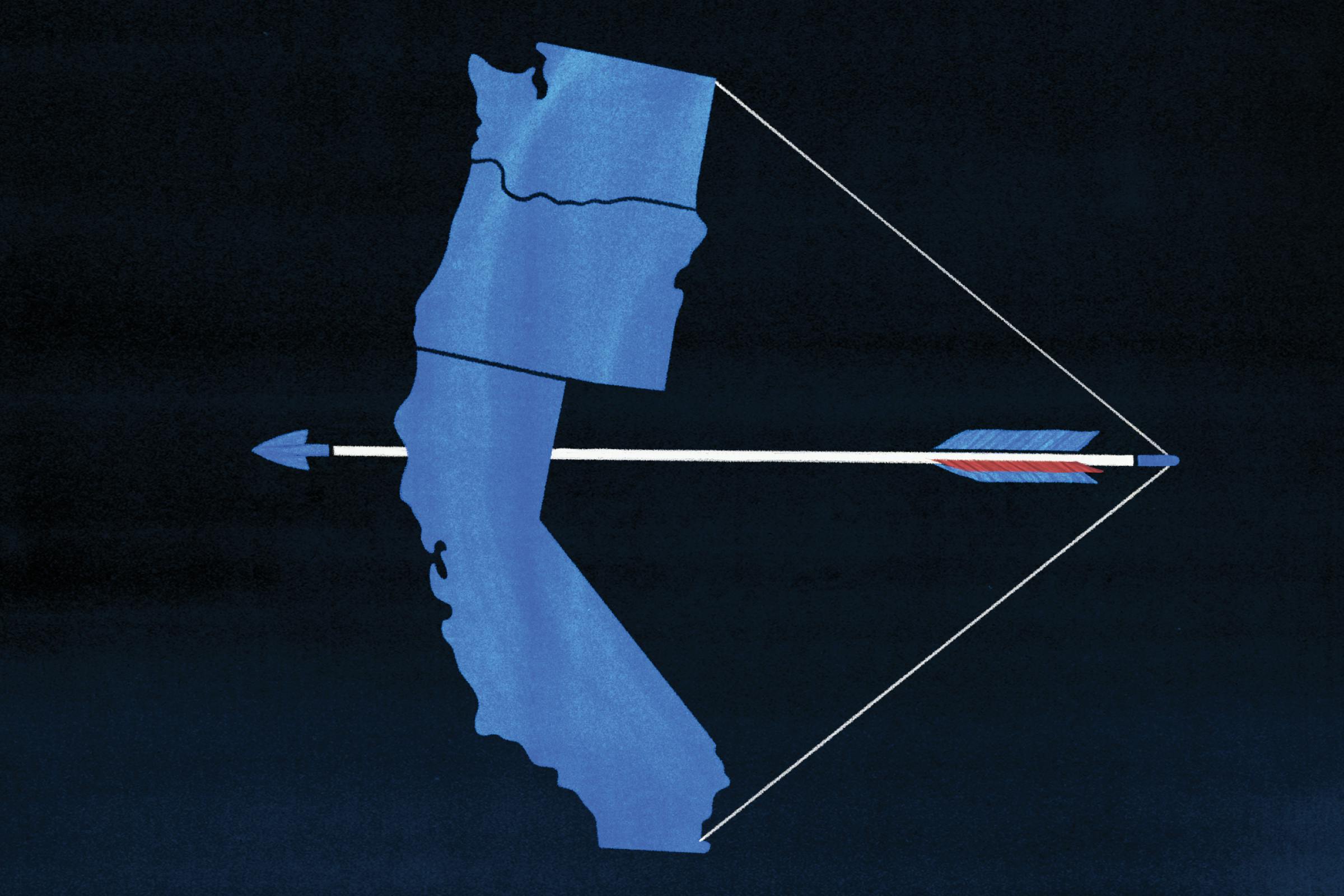

Nobody from the West Coast has ever won the Democratic presidential nomination. But two years from now, at least six will likely be competing for it: a mayor, a governor, at least two senators, even a few business executives. Tom Steyer, a venture capitalist from San Francisco, has already spent $40 million on a national ad campaign calling for President Trump’s impeachment and has held town halls in Iowa and New Hampshire. Jay Inslee, the governor of Washington, headed to Iowa in June, where he gave the keynote speech at a Democratic Party function outside Des Moines. Eric Garcetti, the photogenic mayor of Los Angeles, was there just two months before. On a swing through the Northeast in May, Garcetti also stopped by New Hampshire. (Senator Kamala Harris of California and Howard Schultz, the former CEO of Starbucks, are widely seen as presidential contenders as well, though so far they have refrained from visiting the early primary states.) The flurry of trips is instructive. With Donald Trump in the White House, a group of gifted politicians and public figures from the Pacific Coast believe that they are the best positioned to challenge him.

They may be right. A special brand of American liberalism, at once independent-minded and dedicated to the common good, has flourished in the West. And it could well be this tradition—with its commitment to immigrants, to equality, to free trade, and to environmentalism—that provides the best path forward for Democrats looking to unite their fractured base.

Americans tend to think of the West Coast as a liberal fortress. But not so long ago, Washington, Oregon, and California supported Republicans. (Much of the rural parts of all three states still does.) Westerners were attracted to the GOP’s valorization of individual independence, an attraction that sometimes manifested as libertarianism. They wanted to be allowed to do their own thing, without interference from the state. This emphasis on autonomy is still apparent. “We’re the people who believe in personal freedom,” Oregon Senator Ron Wyden told me.

Yet what personal freedom means to Westerners is now different from what it means to the GOP. As Republicans started to take more regressive stances on social issues, the desire for independence led voters in Washington, Oregon, and California in another direction, toward advocating for abortion rights, gay rights, and the legalization of marijuana.

With help from the technology industry, all three states also came to support loosening immigration restrictions. Tech startups lobbied for more H-1B visas, and not only because they needed skilled workers from overseas; immigrants or their children have founded 60 percent of tech startups.

Washington, Oregon, and California became strong proponents of free trade, as well. Tech companies, which rely on global supply chains, had strong incentives to block tariffs. So did Hollywood, which in the 1980s started to depend heavily on the international market. Nike, and the sports shoe and apparel companies that grew up around it in the Portland area, make many of their goods in Asia. Boeing, historically the linchpin of the Seattle economy, depends on international sales.

Starting in 1949, with California’s landmark Dickey Water Pollution Act, the West Coast also made itself the role model for environmentalism. More than half a million Californians work in renewable energy, ten times the number of coal miners in the entire nation.

In spite of the West Coast’s early conservatism, or perhaps precisely because of it, Democrats from the region are now uniquely suited to challenge Trump. All told, they have created a platform that is almost the polar opposite of his xenophobia, bigotry, protectionism, and environmental carelessness.

This isn’t to say that these Democrats won’t have obstacles to overcome in 2020; there are plenty. Even though all three states boast some of the highest state minimum wages in the country, housing costs and income inequality are major regional challenges. (California has a higher rate of inequality than Mexico.) Any presidential candidate from these states will have to answer for the problems back home. But of all the critiques leveled at these politicians, their alliance with the tech industry may be the most difficult to overcome.

Several prominent liberals in the Pacific Northwest, like Washington’s Suzan DelBene and Maria Cantwell, worked in tech before they entered politics, and even the politicians who didn’t work in tech rely on its donations: Kamala Harris’s donors are a “who’s who of major Silicon Valley players,” according to The Hill. At a time when some Democrats want the party to take a far tougher stance on monopolistic business practices, these connections could be a liability.

Then again, voters may not be concerned. Even after the Cambridge Analytica scandal of this past spring, the social media giants remain wildly popular. In June, a Pew Research Center poll showed that 74 percent of Americans think major technology companies have had a positive impact on their lives. Middle American cities such as Nashville, Dallas, and Indianapolis are eagerly seeking Amazon’s planned second headquarters, as smaller cities vie for Facebook and Google data centers. “Silicon Valley should be a huge ally to the progressive movement,” said Ro Khanna, a Democratic congressman from California’s 17th district, home of the technology industry.

Perhaps the most powerful reason Democrats from the West Coast have a real shot at the White House is that on many fronts they have been leading the resistance to Trump. Kate Brown, the governor of Oregon, refused Trump’s request to send National Guard troops to the Mexican border. Xavier Becerra, the attorney general of California, has buried the administration in lawsuits, at least 40, on topics as diverse as clean air and 3-D printed firearms. As Trump prepared to gut the Paris climate agreement, the three states made a deal with British Columbia to reduce their own emissions.

The region is likely to be significant for Democrats well before 2020. Of the 23 seats they need in order to take control of the House in November, Democrats hope to pick up eight in California, and as many as three in Washington. And now that its primary falls earlier in the presidential cycle, soon, not only will Californians need to visit Des Moines; Democrats from the Midwest and the East will have to make pilgrimages to California. As a result, state Senator Ricardo Lara has said, they will no longer be able to treat as “afterthoughts” issues that are for the West—and ought to be for the nation—of utmost importance.

The participation of former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon at The Economist’s Open Future festival this month caused a great deal of controversy. But the actual interview he gave was fairly predictable. Free trade and immigration have been bad for the United States and Europe, argued Bannon, a view he shares with other right-wing populists. Interviewer Zanny Minton Beddoes, meanwhile, defended the liberal viewpoint which sees free trade and immigration having broadly increased prosperity. “We will have you back in a few years,” Beddoes said to close the interview, “when we will see which of these world-views proved to be the right one.”

Beddoes’s closing statement might have been casual, but it revealed an interesting assumption: that these sorts of disagreements, between liberal and right-wing populist politics, can be settled by empirical evidence. Once the right-wing populist agenda has been implemented for a few years in countries such as Hungary, Italy, the USA, so this assumption goes, experience will show that following populist policies did not bring about the promised results, leading to disillusionment with populism. This is also the logic behind articles addressed at Trump supporters, highlighting the discrepancies between what he promised to deliver, and what he is in fact delivering. The implicit claim is that voting for politicians and policies is like adopting a theory about how the world works, one that experience can later either confirm or falsify.

This line of thought echoes the way the twentieth-century Austrian philosopher Karl Popper thought science works: Scientists put forward a theory which they then test against experience. If experience contradicts the theory’s predictions, the theory is “falsified” and should promptly be discarded. Popper saw science as the model of critical and rational thinking, always open to being shown that it was wrong, always accountable to empirical evidence. He also saw science as a model for democratic politics. In a democracy, the government should always be open to criticism, and it should of course be accountable to voters, who test the degree to which government policies work or not. If not, they get rid of them in the next election and vote in a new government.

The problem is that science doesn’t actually work that way—and neither do democratic politics.

In 1965, the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science in London, featured a debate including Popper and a young American historian and philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn. Popper was by then 63 years old and an eminent professor of philosophy at the London School of Economics, whereas Kuhn was a 43-year-old academic who had failed to get tenure at Harvard, and whose first book on the philosophy of science had only been published three years prior. Unlikely as it might have seemed then, Kuhn turned out to be the more influential philosopher of the two, with The Structure of Scientific Revolutions selling over one million copies.

Research shows that voters tend to exculpate the party they support, continuing to support them even in the face of apparent shortcomings.Whereas Popper saw scientists as always engaged in attempts to test the truth of the dominant theories of their time, Kuhn understood science as for the most part a conservative affair, with scientists conforming to the scientific status quo of their day. Kuhn argued that most of the time scientists work towards developing the available theories, rather than putting them on trial. More importantly, according to Kuhn, scientists stick to a theory even in light of observations that seem to contradict it. Having faith in the overall validity of the theory, they make allowances to explain away any apparent contradictions, putting them down to external factors that have nothing to do with the theory itself. A famous example of this is the now-discarded vision of an earth-centric solar system. Having accepted Aristotle’s theory that the sun and planets moved around the Earth in perfect circles, Ptolemy was faced with observations that showed the planets were moving differently. Instead of taking that empirical evidence to signify that Aristotle’s cosmology was wrong (which of course it was), Ptolemy postulated the existence of some extra circular motions the planets made, called epicycles, that resulted in his observations being made compatible with Aristotle’s cosmological thesis.

In other words, scientists act towards scientific theories less like dispassionate referees, out to catch any mismatch between theory and experience, and more like partisan supporters who blame anything but their adopted theory. This resembles the behavior of the electorate, too. Instead of holding governments accountable to the results they promised, research shows that voters tend to exculpate the party they support, continuing to support them even in the face of apparent shortcomings. Given the levels of devotion that populist politicians inspire today, their voters are unlikely to recognize any future failures of their policies as evidence: Even if immigration cuts and tariffs fail to bring back jobs to the U.S. and raise workers’ wages, voters are unlikely to blame Bannon’s world-view. After all, there is already evidence that the policies he supports don’t work.

But Kuhn did see a means through which true change could come—both in science and politics, whose revolutions Kuhn saw as fundamentally similar. Even though revolutions—profound shifts in thought—are a response to inherent problems, mere arguments and empirical evidence pointing out the problem aren’t enough to start them, Kuhn argued. A compelling alternative theory also needs to be available. Moreover, since two competing theories lack enough common ground to agree on an evaluation of the arguments and evidence, a level of faith in the new theory is needed, as well as persuasion by rhetoric and other non-evidence based means.

Although we are not yet facing a revolution, Kuhn’s remarks have a familiar echo in our current political moment. Despite addressing real grievances, the rising tide of populism seems to be less the result of rigorous argument and evidence, and more the result of effective rhetoric and the cult-like devotion populist politicians inspire in their followers. What is more, we are witnessing the absence of any common standards that opponents and supporters of populist politics can use to engage one another in an exchange of arguments, rather than talk past each other. Bannon’s interview was a case in point.

For those who wish to defeat the agenda of populism in Europe, the U.S. and beyond, Kuhn’s insights suggest a specific approach: The battle has to be won just as much at the level of rhetoric and persuasion as anywhere else. For better or for worse, people are easily persuaded when what you’re offering is a quick solution to a problem they’re facing. According to Kuhn, the Copernican revolution didn’t take place when new observations were made. It was the result of society’s need for a more accurate calendar, and astronomers’ faith that this new Copernican astronomy could quickly provide it. (In fact, it didn’t.) Rhetoric as a means of persuasion is also very effective. It is often looked at with suspicion, as the appeal to brute passion and emotion over reason, as a technique of manipulation. But even good arguments are more powerful when delivered with rhetorical verve, something effective change-makers have always understood. Despite Dr. Martin Luther King’s brilliance as a political thinker, it was the emotional impact of his speeches and his practice of non-violence that made him so influential in the struggle for civil rights.

Populists have been aiming very effectively at this emotional impact. Defenders of the liberal order need to as well. Simply waiting for experience to prove populist politics wrong won’t work—that strategy doesn’t even work in science.

Several areas of southeastern North Carolina are still facing dangerous conditions from Hurricane Florence, the catastrophically wet storm that crawled over the state more than a week ago. But the Outer Banks are open for business. Miraculously, the state’s 18 highly developed, low-lying barrier islands were spared Florence’s worst effects; preliminary reports showed only a few million dollars in damage. “We were really blessed on this one,” resident Matt Paulson told the local Fox affiliate.

The state’s Republican politicians were blessed, too. Because if Florence had hit the barrier islands directly, they would have been blamed for making the damage far worse than it had to be. In 2012, North Carolina’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a law allowing developers to ignore the latest climate science showing that sea-level rise would essentially drown the islands by the century’s end. As a result, according to The Washington Post, “Billions continue to be invested in homes and condos on low-lying land,” as well as bridges and roads.

When a powerful hurricane like Florence does target the Outer Banks in the future, as one inevitably will, lawmakers will have to account for the preventable devastation their climate law engendered. For now, though, they only have to grapple with the not-insignificant damage from Florence—some of which can also be tied to state lawmakers’ decisions in recent years.

One of the biggest concerns as Florence approached the mainland was that floodwaters would inundate coal ash pits, which contain the metallic waste left over from burning coal. At least three spills have been reported in North Carolina thus far. There’s an ongoing dispute over how much has spilled, because floodwater has still not receded in many areas. But residents living near these ash pits must now worry about exposure to toxins, along with whatever other Florence-related damage they’re already dealing with.

Florence brought record-breaking rainfall and catastrophic flooding to South Carolina, too, but residents there aren’t facing the same problems with the state’s ash pits. Back in 2013, power utilities started removing the waste from the pits alongside coal-fired power plants. The removals were a response to legal challenges from environmental groups over the risks the substance posed to the surrounding community, particularly during flooding events. “Today, every unlined coal ash lagoon in South Carolina has either been excavated, is being excavated or is scheduled to be excavated for transportation to dry, lined landfills or for use in recycling,” according to The Post and Courier.

North Carolina’s power utility, Duke Energy, responded to these lawsuits differently. “They spent years lobbying to try to avoid this litigation,” said Frank Holleman, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center who fought Duke in court. Duke also sought help from North Carolina’s Republican political leaders, donating hundreds of thousands to their campaigns and political committees—particularly during “key moments in state coal ash regulation,” one report noted. In turn, the state’s legislature has often assisted the company in delaying excavation of coal ash storage sites.

Republican lawmakers in North Carolina became more reluctant to allow Duke to delay excavation after one of the company’s pits spilled a massive amount of waste into the Dan River in 2014. The legislature passed requirements for coal ash cleanup and created an independent commission to oversee the work. But then-Governor Pat McCrory, a Republican who had worked at Duke Energy for 28 years, lent a hand to his former employer by shutting down the commission in 2016.

North Carolina still has at least 13 unlined pits filled with millions of tons of coal ash, which risk overflowing or breaching during big rainfall or flooding events. But South Carolina’s present-day reality shows that “this is a totally unnecessary risk,” Holleman said. “The ash does not have to be placed in a pit near a river.”

Hog farming is also a major industry in North Carolina, and Hurricane Florence caused dozens of man-made ponds filled with pig feces to overflow. Last week, The New York Times reported that “at least 110 lagoons in the state have either released pig waste into the environment or are at imminent risk of doing so.” This was expected: It had happened as recently as 2016, due to Hurricane Matthew, and more devastatingly with Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

North Carolina does not allow newly built industrial hog farms to store urine and feces from their animals in these literal cesspools. But existing farms are still allowed to, despite what happened during Matthew and Floyd. “Environmentally superior technologies exist to handle animal waste, such as the Terra Blue technology, which separates liquid and solid waste, composting the solids,” wrote Rick Dove, a founder of the Waterkeeper Alliance, in a recent Washington Post op-ed. “But the industry has dragged its feet on upgrading its waste management; thanks to friends of industrial agriculture in North Carolina’s legislature, such changes aren’t required by law.”

North Carolina Republicans’ climate myopia, and the consequences of it, are especially instructive given the Republican control of Washington. The Trump administration is ignoring the threat of sea-level-rise on development; last year, he rescinded an Obama-era executive order urging federal agencies to consider climate science when rebuilding damaged infrastructure. His Environmental Protection Agency is in the process of loosening several regulations related to coal ash storage. And his chosen leader of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, said it was “despicable” that a pork company had been made to pay $50 million to neighbors whose health was affected by manure lagoons.

In theory, these policies are supposed to benefit the economy. It’s true: Ignoring climate science is a boon for real estate developers, while lenient waste rules are a gift to agriculture and coal industries. But when disasters like Florence strike, these policies are economically catastrophic, as communities are left with an even bigger mess to clean up. Politically, the consequences are less clear. Do North Carolinians regret electing so many politicians who knowingly exposed the state to such predictable disasters? And will we be asking this question about all American voters in the years to come?

No comments :

Post a Comment