A record-breaking hurricane slams into a United States territory. The U.S. government is supposed to respond to the damage. But the government is overstretched, and the island is remote. Amid poor transportation, the response suffers. Thousands die.

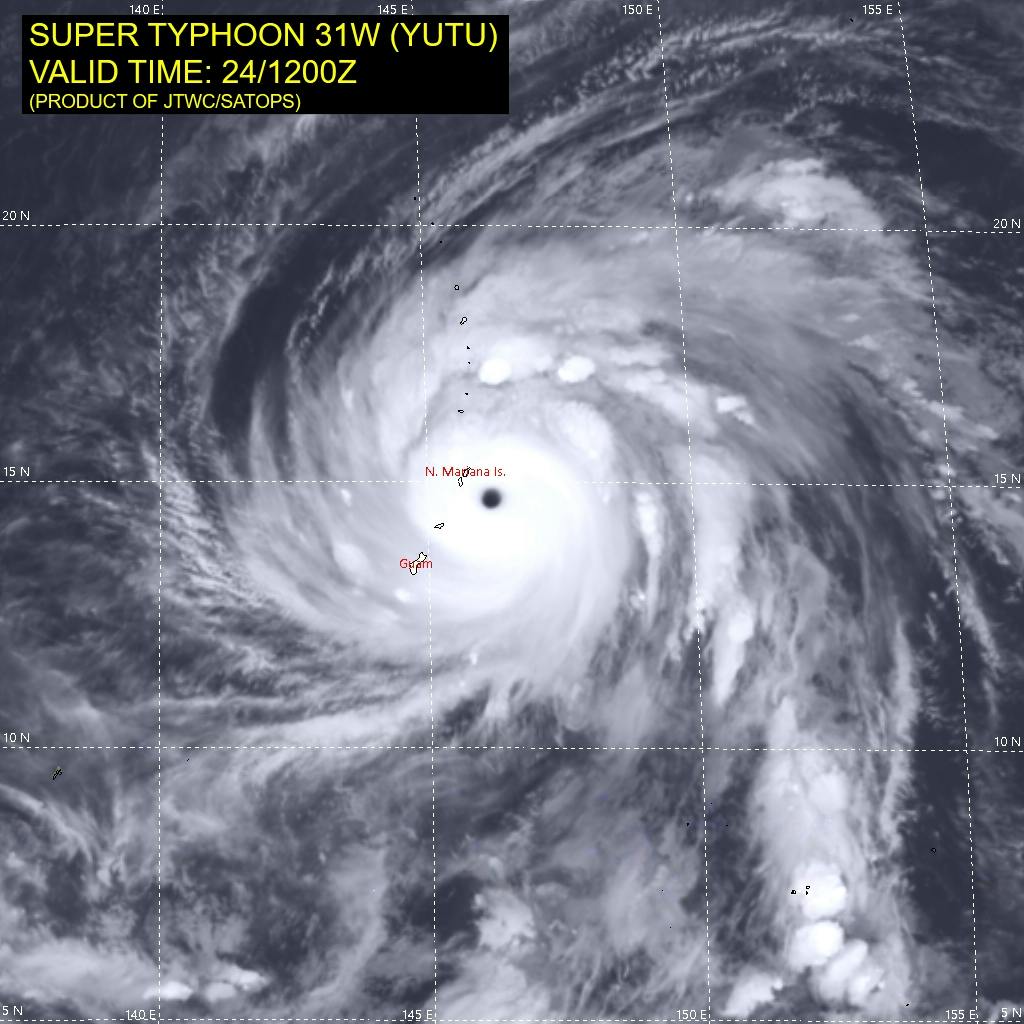

This might sound like the story of Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria. But it could easily become the story of the Northern Mariana Islands and Super Typhoon Yutu, a Category 5-equivalent storm that passed over the U.S. territory in the Pacific Ocean on Wednesday. In the northwest Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; super typhoons are hurricanes with sustained winds above 150 miles per hour. And based on early estimations, Super Typhoon Yutu may be the strongest hurricane to ever hit U.S. soil, a devastating reminder both of the precarious, second-class citizen position of U.S. territories and of the storm readiness issues the U.S. will have to face as climate change accelerates.

Yutu is certainly the strongest storm to form on earth this year. With sustained winds of up to 180 miles per hour, it’s also “likely to be unprecedented in modern history for the Northern Mariana Islands ... home to slightly more than 50,000 people,” according to The Washington Post. The majority of those people live on the island of Saipan—which the storm’s inner eyewall directly passed over—along with the smaller island of Tinian.

Judging from the crickets on major U.S. news sites, who would ever know that a hurricane (#Yutu) is expected to slam into a U.S. commonwealth as a Category 5 storm in about 12 hours? Most of the 53,000 residents of the #northernmarianas are U.S. citizens https://t.co/HSBnZqcxy3 pic.twitter.com/FPGettue3K

— Bob Henson (@bhensonweather) October 24, 2018The degree of damage is yet unclear. But Michael Lowry, a strategic planner for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), predicted a “devastating strike” on Saipan. “This is a historically significant event,” he tweeted, calling Yutu “one of the most intense tropical cyclones we’ve observed worldwide in the modern record.”

Smaller storms have also wreaked havoc on Saipan in the past; Typhoon Soudelor hit Saipan in 2015 with maximum sustained winds of 105 miles per hour and wiped out much of the island’s power infrastructure. A month before that, another typhoon passed over the island and “disconnected an undersea cable, effectively severing communications between the Northern Mariana Islands and the rest of the world for a few days,” HuffPost reported at the time.

Google maps

Google mapsResponse and recovery will likely prove challenging. Saipan and Tinian are extremely remote; the closest large countries are Japan and the Philippines, both of which are more than 1,000 miles away. Hawaii, nearly 4,000 miles away, is the closest U.S. state. FEMA thus considers the Northern Mariana Islands an “insular area,” meaning they face “unique challenges in receiving assistance from outside the jurisdiction quickly.”

Yutu is also striking at the worst possible time. The islands already recovering from Super Typhoon Mangkhut, which slammed into the territory with 105 miles per hour winds last month. Mangkhut prompted President Donald Trump to sign a major disaster declaration for the islands, making federal funding available for both temporary and permanent rebuilding. But a major disaster declaration has not yet been declared for Yutu—only an emergency declaration, which makes federal money available for “debris removal” and “emergency protective measures.”

It’s likely Trump will issue a major disaster declaration for Yutu eventually. But if the past is any indication, it might take a while. His major disaster declaration for Mangkhut, for instance, didn’t come until September 29th—and the storm hit the islands on September 10. Trump was also criticized for his slow response to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico—another remote island U.S. territory that was struggling to recover from an earlier storm when it was hit by an even stronger one. Hopefully, the administration has learned how deadly delay can be.

No matter when, or how, Donald Trump leaves office, he will have dramatically remade the federal judiciary. His administration has struggled to achieve its goals on health care, the border, and infrastructure—but succeeded all too well with the courts. Trump took office with 105 vacancies in the federal district and appellate courts, almost twice the number Obama had in 2009, and Republicans have rushed to fill them, installing more than 50 judges. The impact of these jurists will be lasting; on the circuit courts, they are on average just 49 years old.

Whatever Trump does at the federal level, Democrats still have a fighting chance in the states. Neither Congress nor the president can control the selection of state judges. Term limits and regular elections make them more responsive to popular sentiment than their federal counterparts, who remain in office for life. (Until his death in August, there was a federal judge nominated by JFK on the bench.) This means that even in states like North Carolina, which Donald Trump won in 2016, there can still be a liberal majority on the Supreme Court; and crucially, their decisions are rarely overturned by the federal Supreme Court, which typically avoids interpreting state constitutions.

Some Democrats seem to understand the opportunity this presents. “Everything from family law to much of criminal law to our education system here has been affected by a decision of the state Supreme Court,” said Anita Earls, a civil rights lawyer running for a seat on North Carolina’s top court. Those courtrooms may soon be among the last remaining venues in which to pursue a liberal legal agenda. “The state courts are going to be a place where we’re going to be fighting about all of the issues that are important to people’s liberty, people’s equality,” said Samuel Bagenstos, a law professor from Ann Arbor, Michigan, who is running for the Supreme Court there.

In some states, they already are fighting. In Massachusetts last year, the court ruled that state and local police could not detain immigrants solely to buy time for federal law enforcement to take them into custody. In Pennsylvania this past January, the Supreme Court forced the state to redraw its congressional map, which was so gerrymandered, the justices wrote, that it “clearly, plainly, and palpably” violated its constitution. And in Iowa, in June, the state Supreme Court ruled that “reproductive autonomy” was protected under the state constitution, meaning that abortion would be legal in the state even if Roe v. Wade were overturned.

A more liberal judiciary in other states could make similar rulings possible. While the Michigan Supreme Court has handed down staunch conservative rulings in recent environmental and labor cases, its ideological balance could shift this November, if Bagenstos and one other liberal can win. In Texas, three seats on the Supreme Court are also on the ballot, and if a single Democrat is elected, he or she would be the first liberal to sit on the court in 24 years. Two Democratic candidates for seats on Ohio’s Supreme Court could provide a vocal liberal minority to challenge conservative rulings on voter suppression and gerrymandering. And in April, Wisconsin elected Rebecca Dallet, a candidate backed by state Democrats, to its Supreme Court, which until now has consistently ruled in favor of Republican Governor Scott Walker’s agenda on such issues as public sector unions and his own recall election.

Meanwhile, some states are considering amending their constitutions to address issues that federal courts, now that they are increasingly conservative, won’t address. Florida, for instance, will vote on a major amendment to end felon disenfranchisement, a racially discriminatory practice that the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld as constitutional. If the amendment passes, and the measure is challenged legally, the state Supreme Court, no matter its political leanings, would have to expand ballot access. Colorado, Michigan, and Utah have also advanced state constitutional amendments that, if implemented, would allow independent commissions to redraw gerrymandered districts instead of state lawmakers—a key issue as legislators prepare for redistricting after the 2020 census. And Hawaii’s voters will even decide whether to hold a convention to rewrite their state’s constitution in its entirety.

Republicans understand the stakes and in some instances have resorted to extreme measures to take, or retain, control of the state courts. In August, the West Virginia House of Delegates voted to impeach all four sitting justices on the state’s highest court. Lawmakers defended the move as an effort to restore good government—the justices were accused of lavish and ethically dubious expenditures, including the purchase of a $42,000 desk and a $32,000 couch—but critics saw it as an effort by the Republican state government to seize control. (One of the justices has already retired; the other three will remain on the bench pending a trial to remove them in the state Senate, when they would almost certainly be replaced by more conservative jurists.) In North Carolina, Republican legislators went even further to take back the state court: They have added a constitutional amendment to the ballot in November that would let them pack the Supreme Court with two additional judges. If passed, it would turn a 4–3 Democratic majority into a 5–4 Republican majority.

A dogged focus on the courts is not new for Republicans. “They have made judicial appointments a priority in this country for a long time,” Bagenstos told me. “And on the other side, there has been much less attention until very recently.” Through the Federalist Society and Judicial Crisis Network, conservatives have been able to drive attention—and money—to key fights. When Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, for example, conservative groups outspent liberals nearly 20 to one. Judicial Crisis Network reportedly spent $17 million. There are a few similar Democratic organizations, including Demand Justice, but it was founded just six months ago. Run by Brian Fallon, Hillary Clinton’s former spokesman, it has not yet weighed in on state races. As opportunities at the federal level dwindle, however, that could change.

Donald Trump’s legacy at the federal level may be assured, but the state courts are another matter. The November elections will decide the fate of the House and Senate. But state court races may prove more eventful for Democrats.

Brian Kemp currently holds two significant positions in Georgia politics, and he has been in the news for both of them. As the Republican nominee for governor, he is engaged in a fierce battle with Democrat Stacey Abrams, who, if she wins, would be the first female African-American governor in United States history. Polling indicates an extremely close race, one that could be decided by tens of thousands votes.

Kemp is also Georgia’s current secretary of state, where one of his responsibilities is to oversee state elections. In that capacity, he has been engaged in a systematic campaign to restrict the number of Georgians allowed to cast ballots. In July 2017, Kemp’s office purged nearly 600,000 people, or 8 percent of the state’s registered voters, from the rolls; an estimated 107,000 of them were cut simply because they hadn’t voted in recent elections. This year, Kemp has blocked the registration of 53,000 state residents, 70 percent of whom are African-American and therefore could be reasonably expected to vote for Abrams.

Both moves were entirely legal. Georgia, plus at least eight other states, has a “use it or lose” law that allows it to cancel voter registrations if the person hasn’t voted in recent elections. The state also has an “exact match” law, enacted last year, whereby a voter registration application must be identical to the information on file with Georgia’s Department of Driver Services or the Social Security Administration; if they don’t match, or no such information is on file, then the registration is put on hold until the applicant can provide additional documents to prove their identity. That’s why more than 50,000 applicants are on hold. (They can still vote, with a photo ID, but no doubt their pending status will discourage many.)

Georgia is only one of a number of states attempting to artificially suppress the (Democratic) vote, making voting rights a key issue in this election—not to mention 2020, when Donald Trump seeks a second term. With critics insisting that many state laws restricting voter registration are unconstitutionally discriminatory, a continued series of court tests is inevitable. The Supreme Court thus may be the ultimate arbiters of who is allowed to vote and who is not. This is not the first time the court has been cast in such a role, and history does not beget optimism.

Beginning in 1876, the Supreme Court presided over a three-decades long dismantling of what seemed to be a constitutional guarantee of the right to vote for African-Americans. The groundwork was laid in May of that year, when, in United States v. Reese, the court determined that the 15th Amendment, which states that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged…on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” did not mean what it seemed to mean.

As Justice Joseph Bradley wrote in a companion case, the amendment “confers no right to vote. That is the exclusive prerogative of the states. It does confer a right not to be excluded from voting by reason of race, color or previous condition of servitude, and this is all the right that Congress can enforce.” Bradley thus transferred the burden of proof from the government that has denied someone’s right to vote to the person whose right has been denied, a bar that would prove impossibly high.

In 1880, in a pair of cases decided the same day, the court overturned a West Virginia law that, by statute, limited jury service to white men, but sustained a murder conviction by an all-white jury in a Virginia case because, although no African-Americans were chosen to serve on juries, there was no specific law that prevented it. Southern whites got the idea. As long as a law did not announce its intention to discriminate, it would pass judicial muster.

When Justice Bradley, writing for an 8-1 majority in the Civil Rights Cases in 1883, declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional and announced that black Americans would no longer be “the special favorite of the laws,” white supremacists in the South ramped up their efforts to keep black Americans from the ballot box, employing terror, fraud, and a series of ludicrous contrivances.

South Carolina, for example, introduced a device called the “eight-box ballot,” equipped with eight separate slots, each designated for a specific candidate or party. To cast a valid vote, a person was required to match the ballot to the correct slot, but the manner in which the ballot and the box were labeled made it virtually impossible for someone not fully literate to do so. Whites were given assistance by agreeable poll workers, while blacks, most of whom could read only barely or not at all, were left to try to decipher the system on their own.

Still, despite all efforts to stop them, African-Americans throughout the South continued to risk their lives and property in order to try to cast ballots. In 1890, armed with the roadmap supplied by the Supreme Court, Mississippi called a constitutional convention to end black voting once and for all.

The new state constitution required that, in order to register, potential voters be Mississippi residents for two years, pay an annual poll tax, and pass an elaborate “literacy” test, which required an applicant to read and interpret a section of the state constitution chosen by a local official. The “understanding and interpretation” test was meant not only to prevent new registration by Mississippi’s extensive African-American population, but also to disqualify those already on the rolls. Whites were given simple clauses to read (and, again, were often assisted by poll workers) while African-Americans were given serpentine, incomprehensible clauses, which had been inserted into the document for that very purpose. When African-Americans were off the voting lists, they would be stricken from jury rolls as well.

None of this was done in the shadows. James K. Vardaman, a racist Democrat who would go on to become governor and then a United States senator, was one of the new constitution’s framers.

“There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” he said. “Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics … let the world know it just as it is.” Democratic Senator Theodore Bilbo, during his campaign for re-election in 1946, remarked, “The poll tax won’t keep ’em from voting. What keeps ’em from voting is section 244 of the constitution of 1890 that Senator George wrote. It says that for a man to register, he must be able to read and explain the constitution … and then Senator George wrote a constitution that damn few white men and no niggers at all can explain.” As a result, according to Richard Kluger’s Simple Justice, “almost 123,000 African American voters were defunct practically overnight.”

Every southern state eventually followed suit. In 1898, Louisiana convened a constitutional convention specifically to disenfranchise African Americans—“to establish,” a committee chairman at the convention said, “the supremacy of the white race.” After its adoption, the number of registered black voters dropped from 130,344, to 5,320.

Court tests of these new state constitutions went nowhere. In June 1896, Henry Williams was indicted for murder in Mississippi by an all-white grand jury. His attorney sued to quash the indictment based on the systematic exclusion of blacks from the voting rolls, specifically citing the 1890 Mississippi constitution. For most laymen looking at the Mississippi voting rolls, that some organized chicanery had been afoot would have been beyond question.

Yet despite the fact that virtually none of the state’s 907,000 black residents were registered voters, and state officials had publicly announced their intention to disfranchise them, the court ruled that the burden was on Williams to prove, on a case-by-case basis, that registrars had rejected African-American applicants strictly because of race. Justice McKenna wrote that the Mississippi constitution did not “on [its] face discriminate between the races, and it has not been shown that their actual administration was evil; only that evil was possible under them.”

The final blow to African-American voting rights was struck in 1903 in Giles v. Harris, when the court rejected a challenge by Jackson W. Giles, a Montgomery janitor who had voted for two decades, to the registration provisions of Alabama’s 1901 constitution, which contained the usual poll tax, literacy requirement, and a grandfather clause (automatic registration if one’s father or grandfather had been registered).

In a perverse majority opinion, Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed that since Giles insisted “the whole registration scheme of the Alabama Constitution is a fraud upon the Constitution of the United States, and asks us to declare it void,” he was suing to “to be registered as a party qualified under the void instrument.” If the Court then ruled in Giles’s favor, Holmes concluded, it would become “a party to the unlawful scheme by accepting it and adding another voter to its fraudulent lists.” This is the very definition of reductio ad absurdum. By Holmes’s reasoning, any law that was discriminatory would be a “fraud,” and the court would become party to that fraud by protecting the plaintiff’s right as a citizen.

To avoid the problem, Holmes could have struck down the offending sections, and asserted that any state provision that, in word or application, violated the fundamental tenets of equal access to the ballot box would also be void. But he chose not to. Law professor Richard H. Pildes described Giles as the “one key moment, one decisive turning point … in the bleak and unfamiliar saga … of the history of anti-democracy the United States.” With the court’s complicity, by 1906, more than 90 percent of African-American voters in the South had been disfranchised. Unable to influence politics through voting, and with no recourse in federal court, African-Americans were forced to stand by helplessly as the horrors of Jim Crow took root across the South.

Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses are all illegal now, and so, as Brian Kemp and other Republicans have demonstrated, disfranchising black voters has needed to become ever so slightly more sophisticated. And certainly Kemp doesn’t brag about it like Vardaman and Bilbo did. Still, both the tactics and the intent are frighteningly familiar.

In deciding any voter suppression cases that come before it, the Supreme Court will have a stark choice. It can emulate decisions that upheld laws enacted solely and unapologetically to steal the right to vote from millions of African-Americans, or it can recognize the discriminatory and racist intent of these laws and strike them down.

But just as the distant past doesn’t beget optimism, neither does recent history. Back in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the heart of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, ruling in Shelby County v. Holder that it was unconstitutional to require nine mostly Southern states to seek federal approval before changing their election laws. “Our country has changed,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote for the 5-4 majority, which included swing Justice Anthony Kennedy. “While any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.”

Five years later, the disastrous effects of that ruling have become apparent. Nearly 1,000 polling places across the country have been eliminated since Shelby. As the Pew Trusts reported last month, “The trend continues: This year alone, 10 counties with large black populations in Georgia closed polling spots after a white elections consultant recommended they do so to save money.” With Kennedy’s seat now occupied by the significantly more conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh, it’s fair to doubt that this court would find such trends any more troublesome than those that ruled during one of the darkest periods in American history.

No comments :

Post a Comment