This week, The New York Times obtained a draft memo leaked from the Department of Health and Human Services. It argues that the government needs to establish a binary definition of gender, particularly for the purposes of enforcing Title IX—the law stipulating that nobody can be discriminated against on the basis of sex in an educational context receiving federal funding. The new definition would have people defined as either male or female, according to the genitals observed at their birth, with disputes resolved by genetic testing. The memo suggests that gender would be defined “on a biological basis that is clear, grounded in science, objective, and administrable.”

The Office for Civil Rights at HHS is run by Roger Severino, an ideologue with a history of opposing queer Americans’ rights (he has defended gay “conversion therapy” and railed against gay marriage). It is not at all clear that the substance of the memo will be enacted in any form; that it was leaked by the White House suggests it is a provocation designed to inflame and divide voters in advance of the midterms. But there are two aspects to the document that reveal the utter bad faith in which the Trump administration, and Republicans more broadly, are engaging in the issue of gender.

The first is very simple. HHS proposes to pin down sex as a matter of biological certainty that can trump a person’s claimed gender. But the concept of two “biological sexes” is inaccurate. For example, all babies are not born with bodies that can be neatly categorized. The Intersex Society of America estimates that 1 in 1,500 to 1 in 2,000 babies are born with genitals that do not appear obviously male or female. That is a very large population of intersex Americans, whose existence would be falsely recategorized by this memo’s proposed view of sex.

For many years, intersex people have been encouraged or forced, via surgery, to identify with one gender and then “live as a woman” or “as a man.” But that just hasn’t worked, instead leading to great unhappiness for many people. The medical consensus now is that intersex people need to determine their gender for themselves, or risk serious psychological trauma.

It is a mistake to turn intersex people into a kind of “test case” to back up trans people, both because it’s reductive of intersex people’s experiences and because it wrongly implies that trans people’s gender identities have anything to do with their genitals. But the two groups are strongly allied, because trans and intersex people have both been harmed by the imposition of a binary view of birth gender—precisely what HHS wants to do now.

The medicalized view of gender assignment contained in the HHS memo runs contra to everything that research tells us about how gender actually works. But the “two genders and nothing else” idea is repeated over and over again by conservatives who think that there is a vast social justice campaign to undermine traditional American family values, under the umbrella term of “gender ideology.”

That mistake is the core piece of misinformation spread by the HHS memo. But there’s a second, more conceptual element to the memo’s perniciousness. It frames gender—a complex phenomenon that evolves through time and varies according to individual—as something basic and biological: as something “that is clear, grounded in science, objective, and administrable.” In doing so, the memo reduces the conversation around gender down to body parts. It turns the question of trans rights—the rights to be a free person in every legal respect—into a humiliating, dehumanizing debate about penises and vaginas. It demonstrates a refusal on the part of HHS to consider trans people as full human beings, with minds as well as bodies. Worse still, it forces all of us to argue for trans rights on those specious grounds.

That’s not a coincidence. Again and again, fights over civil rights in America (for black people, for gay people) have turned into fights over the barest, basest facts of life—whether this person can copulate with that person, whether this person can use a certain bathroom. The very premise of these debates contains the suggestion that the offending parties are not quite human, or that they have somehow transgressed the bounds of personhood.

This dehumanization is baked into the memo’s design. Want to be considered full, free, trans human beings? First, the memo says, let’s have a conversation about your genitals. Then we can talk about your rights. Because the memo sets the boundaries along those lines, advocates for trans rights can become trapped in an argument that works against them. The debate itself ends up transmitting the memo’s junk science and junk presumptions into the culture, where it can fulfill its purpose of engendering inequality.

There are many precedents for bringing the debate about rights down to the lowest possible denominator. In the nineteenth century, people claimed that mixed-race people were unable to have children, the same way that mules are infertile. It was patently untrue even at the time, but public “debates” over the claim meant that mixed-race people’s lives were always discussed in this degrading context.

In that case and in this, the political discussion purports to be scientific and objective. But it instead manipulates the terms of the conversation to be about organs, not hearts and minds. Trans people are, like any other group, citizens who vote. The leaked HHS memo is a cynical attempt to provoke a firestorm in our culture, in order to draw ever starker lines between the left and the right. But we can’t fall for it. If trans activists are reduced to talking about their genitals at the expense of talking about their human experience, then we are all degraded.

The killing of other human beings in war makes graphic an abiding moral dilemma: You might try to make an evil less outrageous, or you might try to get rid of it altogether—but it is not clear that it is possible to do both at the same time. In one of her Twenty-One Love Poems, Adrienne Rich imagines imposing controls on the use of force until it all but disappears: “Such hands might carry out an unavoidable violence / with such restraint,” she writes, “with such a grasp / of the range and limits of violence / that violence ever after would be obsolete.” Yet the lines contradict themselves: If violence is inevitable, however contained or humane, it is not gone.

Nick McDonell’s striking new book about America’s forever war, The Bodies in Person, is a call to contain or minimize one kind of outrageous violence: the killing of civilians in America’s contemporary wars, fought since 9/11 across an astonishing span of the earth. At a moment when Donald Trump has relaxed controls on American killing abroad even beyond what McDonell chronicles and our long-term proxy war in Yemen has broken into gross atrocities—like the Saudi air strike that killed scores of civilians in early August this year—it is a pressing theme. And McDonell’s appeal for Americans not only to attend more to the military excess of the war but also to bring down its civilian toll in the name of the country’s own founding ideals is nothing if not noble.

THE BODIES IN PERSON by Nick McDonellBlue Rider Press, 304 pp., $28.00

THE BODIES IN PERSON by Nick McDonellBlue Rider Press, 304 pp., $28.00Pulsating with attention to moral principle, McDonell’s approach to this grisly reality is also highly personal. In his reporting, he restores the identities of civilian victims. “The first step away from a person’s name is the first step toward killing him,” he observes. He gives voice to misgivings that lurk beneath the surface of American consciousness, close enough to cause trouble but submerged too far to break through without help. Instead of explaining the world-historical setting of our wars or presenting another gritty narrative of soldiering abroad, McDonell is interested in how the military thinks, constantly asking our soldiers and their leaders hard moral questions. And yet, fixated on the range and limits of violence, he neglects to ask why our country treats it as unavoidable in the first place.

McDonell comes to the subject of American war as a disillusioned member of his country’s elite. He first became known as a prep school novelist, starting with the publication in 2002 of his smash hit Twelve, composed when he was only 17 years old and still a student at Riverdale Country School in New York. He wrote what he knew: Park Avenue apartments with absentee parents and posh drug dealers. This was the scene in which McDonell set a crime thriller, later made into a film with Kiefer Sutherland. It was both an ambitious undertaking and a remarkably insular vision.

After his years as a Harvard undergrad, McDonell must have concluded that he wanted to learn about more of the world. His third novel, An Expensive Education, marked a transition. Set partly in Somalia, it was still populated by young American elites, but the characters show their growing awareness of the global system of exploitation upon which their own privilege rests. They continent-hop, enjoying their position while also indulging in caustic irony from the top; they amuse themselves without believing anymore in the “stifling orthodoxies” of America’s “ill-conceived experiment in liberty.” The novel marked McDonell’s own evolution along the same lines: “I didn’t always think this way,” McDonell declares at the beginning of The Bodies in Person. “Halfway through my life my country went to war abroad.”

The realities of America’s global presence began to hit home for McDonell as he traveled the world, giving up fiction for reportage, but still equipped with a novelist’s sensibility and style. Afghanistan and Iraq have been his destinations, as he has embedded with ordinary soldiers and engaged in dialogue with higher-ups in the chain of command. Nearly a decade ago, McSweeney’s brought out his nonfiction book The End of Major Combat Operations, a disquieting look at America’s earliest attempt to withdraw with honor from the quagmire it created in Iraq. After a stint at the University of Oxford, McDonell wrote a book of political theory on nomads and their lack of representation in the international system of states. But America’s war kept drawing him back to the field and to the stifling orthodoxies of those who wage and support it.

Kabul, 2015. In recent years, the United States has turned to drone strikes and special forces. Gueorgui Pinkhassov/Magnum Photos for ICRC

Kabul, 2015. In recent years, the United States has turned to drone strikes and special forces. Gueorgui Pinkhassov/Magnum Photos for ICRCAmerican elites have, of course, discovered their country’s wars in prior generations. Fiction about and reportage on the moral realities of American conflict have long been a staple of the publishing industry, as generations of writers have dramatized the commitment of the soldiers while also offering skepticism about the missions on which they have been sent. “As if anyone needs another lyrical American war story,” one of McDonell’s cutting footnotes rightly observes, “when Michael Herr’s Dispatches is in every guesthouse from Kerada to Taimani.”

Like Herr’s and other earlier books, The Bodies in Person works through a series of narrative set pieces: McDonell witnesses the violence itself and studies its various aftermaths, like a seismologist traveling to assess the damage of an earthquake at various ranges from the epicenter. He movingly narrates the death of “Sara,” a young Iraqi girl from Tikrit who has been recuperating after a lifesaving operation, only to be killed by a bomb meant for the ISIS stronghold across the street. Like much prior literature in this vein, McDonell’s book recalls his own firsthand experiences, as he recounts his interactions through “fixers” with ordinary people in one scene, and then tells of jumping a helicopter to an undisclosed location in southern Afghanistan to observe American forces target and kill an enemy.

But through these stories, McDonell is preparing a very specific moral inquiry: How much should Americans contain their violence? Inside the computerized room where the group executes an air strike, McDonell surveys the protagonists, putting a human face on a general and his subordinates (and contractors). If every victim deserves a proper name, those who perpetrate their deaths are named too. These are troops who follow orders, assuming they are just, tolerating civilian fatalities as collateral damage; McDonell, outraged, wants to probe whether they are right to do so, and poses deliberately naive questions. “I’m trying to figure out in my own head,” he tells Callie, a private contractor from Missouri, “whether it is appropriate sometimes to kill people to get what we want.”

According to international law, it is. You can never aim at civilians, the law says. But it is not against the rules to kill civilians “collaterally,” so long as doing so is not out of proportion to the concrete and direct military aim, and so long as you take precautions to avoid or minimize harm. Given the consensus around this vague rule, for better or worse, the question is not whether this rule makes sense, but what it means in operations on the ground. What counts as disproportionate? And who decides? The law does not specify what number of civilian deaths counts as too many to allow attack. It all depends on what the military aim is—and who makes the calculation of how much harm is too much.

McDonell doesn’t delve into these questions as legal matters (he dismisses “legalese” at one point) but looks at how American policy defines acceptable violence—the killing of enemies and even civilians in the bargain, just not too many. He is especially concerned, it turns out, with how much of the decision-making is left to personnel on the ground, as he investigates the so-called Non-Combatant Casualty Cutoff Value (NCV)—the maximum number of civilians likely to be killed before troops have to ask Washington for permission to strike. This number was, according to McDonell’s reporting, 20 during the heat of the Iraq counterinsurgency, ten in Iraq more recently, ten in Syria during the campaign against the Islamic State, and zero in Afghanistan, after a higher number stoked popular outrage and anti-government protests.

Stretches of The Bodies in Person examine how the United States manages the optics of war, notably through policies that undercount collateral deaths. As a much-noted New York Times Magazine article by Azmat Khan and Anand Gopal last fall detailed, and as McDonell confirms, part of the callousness of American policy has been that it trivializes the scope of the damage after the fact. McDonell also covers the activities of the “Civilian Casualty Mitigation Team,” engaged in the macabre work of “consequence management” when civilians are injured or killed. A disturbing but fascinating system has been erected by the United States to offer payments for “solace” to next of kin, without taking blame for the deaths. “They don’t necessarily imply responsibility,” one lawyer tells McDonell. All they say is, “we’re very sorry this has happened.”

McDonell’s ultimate worry is not exactly that the number of civilians who die in America’s war is too high; it is that any civilians die at all. Human life, he reasons, is equally valuable, no matter where its bearer breathes and toils, and the United States should therefore set the NCV at zero. America’s current use of the NCV, allowing a certain number of civilian casualties, makes American lives “more valuable than others, which is contrary to the American axiom that all men are created equal.” McDonell dramatizes the facts of American carnage in Afghanistan and Iraq so powerfully that it’s difficult to criticize his sentiments.

The only way to ensure that no civilians are killed is to end this war altogether—something McDonell, like other American elites, is not ready to demand.But as the main conclusion of The Bodies in Person, this seems wrong. All policies, including those affecting Americans alone, value lives differently. And as McDonell himself reports, the NCV is already at zero in Afghanistan. Setting it there has by no means ended the bloodshed but has only required units to seek permission from a higher authority before they incur collateral damage. Last year alone, over 10,000 civilians were killed or wounded there, according to a United Nations report. And it’s hard to imagine that any army could completely avoid harming noncombatants while engaged in a conflict. The only way to ensure that no civilians are killed is to end this war altogether—something McDonell, like other American elites, is not ready to demand.

McDonell’s chief mistake may lie in focusing on civilian death as the source of the most serious immorality of American war in the first place. After all, in war, troops die too, and calls to contain violence against civilians (or combatants) in war could function unexpectedly to make war more humane and, therefore, more likely to last longer. Indeed, asking for war without collateral damage is like asking for policing without brutality: It would not tend to end it, but to perfect it as a form of control and surveillance. We don’t know enough about how precisely changes in the NCV in Afghanistan have altered the war. But, even if drones are less and less likely to make mistakes, we do know that on the ground ordinary Afghans complain that their presence above is felt as an oppressive menace. Calling for Americans to kill only the enemy, which is what the military is already trying to do, could polish the moral sheen of that menace.

The containment and minimization of violence in America’s war, particularly when it comes to civilian death, have only made it harder to criticize America’s use of force in other countries. As McDonell rightly puts it in an email to the military, “it’s clear that the U.S. has the most robust CIVCAS [civilian casualties] avoidance policy and process in the world (and in history).” And he records Barack Obama explaining, in justification for his new form of light-footprint war:

People, I think, don’t always recognize the degree to which the civilian-casualty rate, or the rate at which innocents are killed, in these precision strikes is significantly lower than what happens in a conventional war.

For this very reason, many of the Americans McDonell interviews think they are fighting a moral war. One of his sources, a colonel, assures him that U.S. policy is “about just not wantin’ to hurt civilians.” “I mean,” he pronounces, “we take our values with us when we go to war.” The policy of avoiding civilian casualties allows the United States to present warfare as a form of virtue, especially to the extent it is increasingly civilian-friendly.

This narrative has only been growing stronger in recent years. Over the second half of Obama’s presidency, the United States moved away from the large ground campaigns on whose final stages much of McDonell’s narrative centers. Instead, the military has lately turned to deadly policing from the air and the deployment of tiny bands of special forces, which America sent to a full three-quarters of the countries of the world last year. Even while Trump has relaxed applicable guidelines for his forces and tolerated the atrocious conduct of America’s Saudi allies in Yemen, he has maintained a twilight war with few boots on the ground or none. To an unprecedented extent, this novel form of war is defined by its attention to the “humanity” of how it is fought.

Which brings us back to the crux of Adrienne Rich’s poem. Is the trouble that there is not enough restraint, or is it the practice of war (or at least this war) itself? The more containment succeeds—leading to less and less objectionable violence, fewer atrocities, and lower body counts, not merely on the American side but also among civilians caught up in the fray and among legitimate military opponents—the more likely it is that the war will continue indefinitely. What if its worst feature is not collateral death, or even violence, but an attempt at global control and ordering that no one opposes?

Lots of care is needed in considering this possibility, yet it is ultimately even more disturbing than the reality that America must do even better counting its casualties and preventing collateral harm. What if, to be blunt, the deepest moral problem with contemporary American war is not its inhumanity but its existence? What if the Pentagon is outrageously mistaken in the details and is outrageously undercounting civilian deaths, but is also entirely correct that it is fighting the most humane war in history? And what if the deepest moral problem with it is not its failures of containment, but the fact that its increasing nonviolence is part of its endlessness and the global hegemony it enforces?

If McDonell doesn’t ask these questions, it may be because of his nostalgia for the standard beliefs of American elites, whose novelist he once seemed to be grooming himself to become. America was supposed to be founded on a new idea—the universal equality of human beings. Yet it has been engaged in global rule for a while now. “The only non-combatant casualty cutoff value consistent with our values is zero,” McDonell insists, even as he knows both that those values have never guided the U.S. military in a conflict, and that noncombatants have been treated much worse in every American war to date. “Insistence on equality, despite its piercingly slow entry onto the rolls of law, is the most powerful aspect of our experiment,” McDonell adds in the vein of conventional American exceptionalism.

McDonell is aware that this is overoptimistic, but he concludes that, because the “worst crimes stem from a failure of imagination rather than any evil particular to our kind or time or nation,” narratives like his own might change the equation someday. I hope so. But if they do, they will need to reckon with the fact that we confront our endless war only partially when we focus on the civilian death and injury (or, for that matter, death and injury generally) that it involves. If this war can last forever because it is so humane—and fought for ends of control and surveillance rather than with the aim of killing enemies to break the will of the other side—then making it less deadly and more humane may extend it only more.

Should nonprofit groups that buy ads supporting or attacking political candidates be required to disclose their donors? The answer would seem obvious. But in the post–Citizens United landscape—where politics are awash in funds from unknown sources, in unlimited amounts—it was entirely possible that when the Supreme Court got the chance to weigh in on that question, it might side with the defenders of dark money.

Last month, though, the court made the decision to let stand a lower-court ruling that forced dark money groups—mostly the nonprofit arms of groups such as the NRA and Planned Parenthood—to disclose the identity of donors who gave more than $200 for the purpose of influencing federal elections. Champions of campaign-finance reform hailed the decision.

“Great news!” tweeted Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island. “A blow to creepy #darkmoney forces.” Defending Democracy, an independent, nonpartisan initiative, tweeted that the ruling was a “major victory against #DarkMoney” and that it would bring more transparency to American elections, “effective immediately.” Ellen Weintraub, the Democratic vice chair of the Federal Election Commission, called the Supreme Court decision a “real victory for transparency.”

This is a real victory for transparency. As a result, the American people will be better informed about who’s paying for the ads they’re seeing this election season.

/2

But the celebration proved premature. The latest FEC disclosure reports, released last week, show that most of these groups are still hiding their anonymous donors despite last month’s court order. It turns out that the new disclosure requirements are not as expansive as the reformers had hoped. There’s a gaping loophole—and Democrats are benefitting from it as much as Republicans are.

In 2012, the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), a nonprofit watchdog, filed a complaint with the FEC against Crossroads GPS, a conservative nonprofit organization co-founded by Karl Rove. CREW alleged that Crossroads, which was spending tens of millions of dollars to support Republican political candidates, was violating federal law by keeping its donors secret.

It wasn’t until three years later, in 2015, that the FEC put the issue to a vote. But the six-member commission deadlocked, as the three Republican commissioners opposed an investigation into Crossroads. Its complaint dismissed, the watchdog sued the FEC for not investigating Crossroads. The case wound its way to the U.S. District Court for D.C., which ruled in CREW’s favor this past August. When the Supreme Court refused to block the ruling, the FEC was forced to issue new guidance earlier this month.

The FEC wrote the narrowest rules possible without running afoul of the courts. The commission didn’t require all nonprofit groups that fund political ads for or against candidates to unmask their donors, as reformers had hoped it would. Instead, it only required this of groups that solicited funds specifically for that purpose. As Brendan Fischer, the federal reform program director from the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center (CLC), explained, the new requirements “won’t ensure disclosure of donors to groups that spend money on ads that don’t expressly tell viewers how to vote.”

For example, if a group raised money with an appeal to increase federal funding for birth control, but then spent the money on ads asking voters to oppose Democratic Senator Joe Manchin in the November election because he supported Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, then it wouldn’t have to disclose its donors. The group would only have to disclose them if it had explicitly solicited donations with an appeal to take down Manchin in the midterms.

So it was no surprise when, on October 15, the FEC released the latest campaign finance filings and all but a few politically active groups continued to hide their anonymous donors. For the period from September 18 (after the court ruling) to September 30, only four of the 17 political nonprofits with independent expenditures—that is, money spent on advocating for or against candidates—disclosed their donors, according to the CLC. Only one of those groups began revealing its donors after the FEC’s new guidance, suggesting that the guidance had little impact on dark money disclosures.

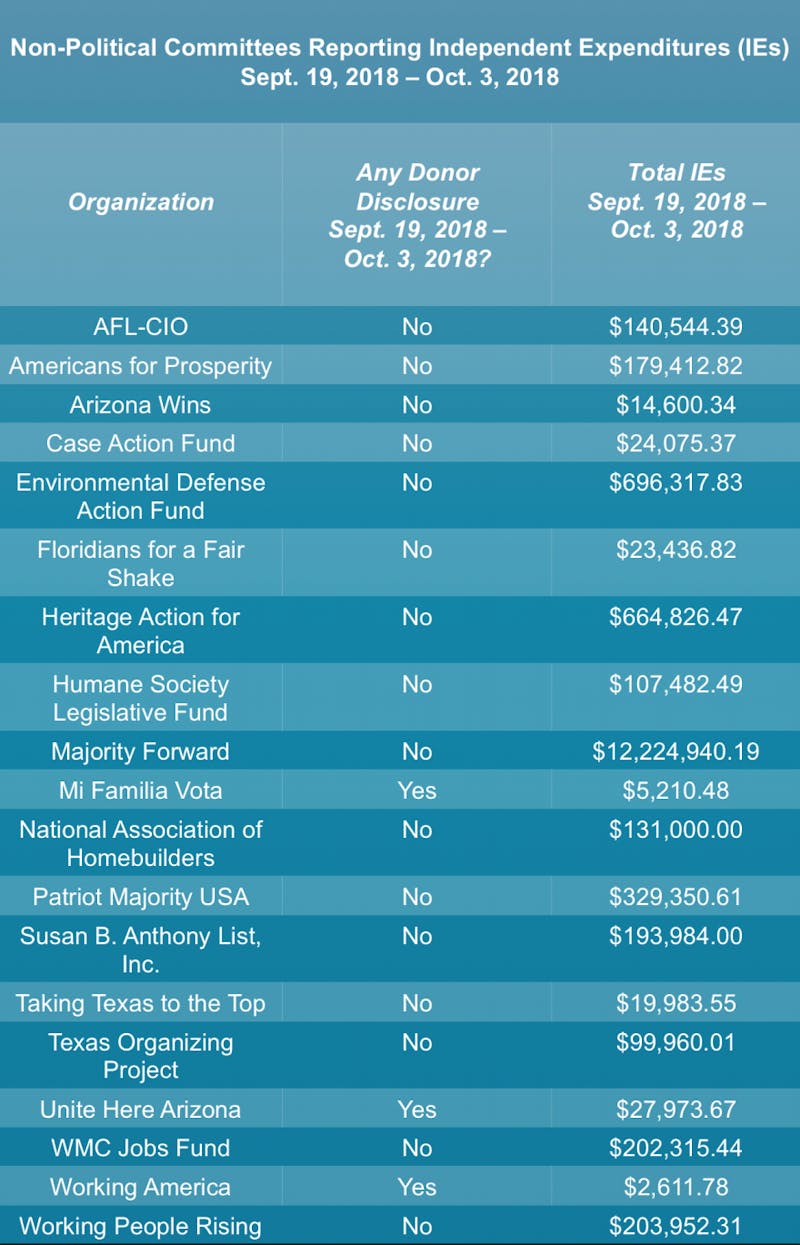

A list of nonprofits with political spending in the third quarter as of October 3. Working People Rising later began disclosing its donors.Campaign Legal Center

A list of nonprofits with political spending in the third quarter as of October 3. Working People Rising later began disclosing its donors.Campaign Legal CenterEven in these few instances, the transparency only goes so far. The four groups, all left-leaning, are Unite Here Arizona, Working America, Mi Familia Vota, and Working People Rising. Their donors are largely labor unions or other nonprofits, and those groups have not disclosed their individual donors. So we still don’t know exactly where the money is coming from.

The Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity, AFL-CIO, Heritage Action and Humane Society Legislative Fund were among the dark money groups that did not disclose their donors. But the group with the most independent expenditures in the third quarter was Majority Forward, a liberal nonprofit connected to the Democratic Senate Majority PAC. The group spent $12 million on political ads between September 19 and October 3, bringing their spending total this election cycle to almost $29 million—mostly on ads against Republican Senate candidates in swing states like Florida, Indiana, and Arizona.

Majority Forward doesn’t disclose its donors thanks to the aforementioned loophole, as its statement to the FEC last week makes clear: “As a matter of policy, Majority Forward does not accept funds earmarked for independent expenditure activity or for other political purposes in support or opposition to federal candidates.”

“Democratic Party officials say they oppose dark money,” the CLC’s Fischer said, “but so far a Democratic group (Majority Forward) is the biggest spender failing to disclose its donors in the wake of this pro-disclosure decision.” (Several other dark money groups, including the right-leaning Patriot Majority and left-leaning Taking Texas to the Top, echoed Majority Forward’s reasoning for not disclosing.)

Weintraub, the FEC’s Democratic vice chair, acknowledged her disappointment: “When we first read the opinion from the court, I think we got a little over excited about what it might be able to do.” But “any additional disclosure is a good thing,” she added, and insisted that there’s “much greater cause to investigate dark money groups, independent expenditures and straw donors now than in the past because of the new disclosure requirements.”

But can her commission keep up with dark money groups? With every new ruling or regulation, it seems, these groups just find another way to remain in the dark. True transparency will require comprehensive action from Congress and the White House to change our campaign finance laws. Anything short of that is just an illusory victory.

President Donald Trump has stuck by Saudi Arabia through every twist of the saga of Jamal Khashoggi, the Washington Post columnist and Virginia resident who was murdered in the Saudi embassy in Turkey earlier this month. He seemingly was the only person in Washington who believed the country’s initial denials of any involvement. When Saudi Arabia followed two weeks of lies with an admission and a bizarre defense—that Khashoggi had been killed after an “accidental fistfight”—Trump accepted that, too. The president has made it clear that all that really matters is the preservation of a $110 billion arms deal reached last year, which he falsely claims will create a million jobs.

“I would prefer that we don’t use, as retribution, canceling $110 billion worth of work,” he said on Friday, later adding, “You know, I’d rather keep the million jobs, and I’d rather find another solution.”

This has put Senate Republicans, particularly the self-appointed torch-bearers of the party’s foreign policy, in a familiar bind. Bob Corker told CNN’s Jake Tapper on Sunday that the Senate had invoked the Magnitsky Act, which could lead to sanctions being placed against Saudi Arabia. Ben Sasse told Tapper, “You don’t bring a bonesaw to an accidental fistfight,” referring to the implement allegedly used to dismember Khashoggi’s corpse. Peter King went even further, telling ABC’s George Stephanopoulos that he thinks the Saudis are “the most immoral government we’ve ever had to deal with.”

But with the exception of the usual exceptions, like the war skeptic Rand Paul, the calls for action have been relatively muted. Some Senate Republicans have even acted as though they’re the real victims of Khashoggi’s murder. Lindsey Graham told reporters, “I’ve been the leading supporter along with John McCain of the U.S.-Saudi relationship. I feel completely betrayed.” And Marco Rubio tweeted this unfortunate formulation:

The #KhashoggiMurder was immoral. But it was also disrepectful to Trump & those of us who have supported the strategic alliance with the Saudi’s. Not only did they kill this man,they have left @potus & their congressional allies a terrible predicament & given Iran a free gift.

— Marco Rubio (@marcorubio) October 22, 2018It’s becoming increasingly clear that, for all their outrage (or mere disappointment) at Saudi Arabia, Senate Republicans have no intention of doing anything about the Kingdom’s murder of Khashoggi. And if that turns out to be true, it will be for same reason that the Senate has backed down time and again since the beginning of 2017. Over the past two years, Trump has systematically demolished one Republican principle after another. The party’s foreign policy moralism would simply be the last one to die.

Despite all the talk of possible rapprochement with Russia, this administration’s most successful foreign policy reset has been with Saudi Arabia. When Trump took office, the long relationship between United States and Saudi Arabia, built on oil and a desire to contain Iran, was in its worst shape in decades. Engaged in proxy wars across the Middle East, the Saudis were opposed both the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, on the grounds that both empowered their enemy.

But a visit from Trump in early 2017 ended in the $110 billion arms deal and, a couple of months later, the renunciation of the Iran deal. After Trump’s visit, CNN reported the “Saudis have begun to view Trump as a like-minded partner—one who put Iran ‘on notice’ early in his presidency and has vowed to take a tougher line on the Saudi nemesis than his predecessor. His team also seems less likely to chide the kingdom on human rights issues, a perennial thorn in the US-Saudi relationship.”

Bin Salman’s successful 2018 visit to the U.S.—and cultivation of elites in American media, business, and, most of all, politics—allowed some skeptics to see what they wanted to see in Saudi Arabia. Promising to remake his country’s oil-based economy, Bin Salman presented himself as a reformer, ending his country’s ban on female drivers in 2017. This image glossed over the Kingdom’s numerous human rights abuses both at home and abroad. The country is deeply engaged in two brutal wars in Syria and Yemen, which is in the midst of one of the worst famines in recent history thanks in large part to a Saudi blockade.

Nevertheless, that famine and Saudi Arabia’s indiscriminate bombing (of a bus filled with 50 schoolchildren, among other horrors), were largely ignored until Khashoggi’s brazen murder. Now, Republicans are having to answer for their support of an authoritarian country, and to figure out how far they can go in sanctioning it without provoking the wrath of a president who would “rather find another solution.” If history is any guide, they won’t go very far at all.

Ever since Trump took office, Senate Republicans have made a big show of pushing back against Trump whenever his foreign policy deviated from the party establishment. But true action has been rare. After Trump accepted Vladimir Putin’s promise that Russia didn’t interfere in the 2016 election, the “outcry, including from Republicans, was instant,” The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos noted. “More remarkable, though, was what didn’t happen. No one resigned from the Cabinet. No Republican senators took concrete steps to restrain or contain or censure the President.”

And even when the Republican-led Senate has taken concrete steps, they have often been symbolic. In response to Trump’s repeated criticism of NATO, the Senate “passed a non-binding measure, 97-2, that expresses support for NATO, its mutual self-defense clause and calls on the administration to rush its whole-of-government strategy to counter Russia’s meddling in the U.S. and other democracies,” DefenseNews reported in July. The Senate passed another non-binding resolution after Trump briefly flirted with the idea of handing over U.S. officials to Russia for questioning. Senate Republicans have also tried strongly worded committee reports and letters to the president.

As long as Trump is the most popular Republican politician in America, and he’s taking the arms deal off the table, it’s unclear what Senate Republicans could do to send a meaningful message to Bin Salman and Saudi Arabia. It’s also unclear that they even want to. From senators Graham and Rubio, there’s the sense that Saudi Arabia’s human rights abuses are better left ignored—that what matters is that they are allies in the fight against Iran. Surely others agree with Trump that one man’s murder does not warrant reneging on a $100 billion arms deal, which might explain why talk of blocking the deal appears not to have nearly the necessary support in the Senate.

The New York Times reported on Saturday that Trump is “betting he can stand by his Saudi allies and not suffer any significant damage with voters.” He’s probably right, and some Senate Republicans probably are making the same wager. The midterms have revolved almost entirely around health care and immigration for weeks now, and that’s not likely to change. Some on the right, notably evangelical leader Pat Robertson, are shrugging off Khashoggi’s murder, which only gives them further cover.

If the Republican Senate ultimately does nothing meaningful to punish Saudi Arabia, it will represent the party establishment’s final capitulation to Trump. This was perhaps inevitable after Senator John McCain’s death in August. Though his own foreign policy views were deeply flawed, there’s little doubt that McCain would have been the most morally righteous Republican voice in this moment, chastising Trump and calling on the Senate to punish Saudi Arabia. “We are not the president’s subordinates,” McCain said upon his triumphant return to the Senate last year, after being diagnosed with brain cancer. “We are his equals.” It’s not clear that any of his surviving Republican colleagues feel the same way.

Earlier this month, on the eve of a federal trial over Harvard’s use of race in admissions, the university’s president invoked the predominant defense of affirmative action: It enhances education for everybody. “Harvard is deeply committed to bringing together a diverse campus community where students from all walks of life have the opportunity to learn with and from each other,” Larry Bacow wrote.

As a professor, I believe in that ideal as deeply as I believe in anything else. But since the 2016 elections, I’ve come to question whether our elite universities believe it. Despite our rhetoric of diversity, we haven’t made a sustained, explicit effort to learn from a significant but typically ignored minority in our midst: Donald Trump supporters.

Since 2016, I’ve had several pro-Trump students come out to me in my office, with the door closed. One student reported that he had heard a slew of egregiously offensive statements by his peers—including “Trump voters are racists, idiots, or both”—but that he hadn’t said anything in response, for fear of drawing ridicule and hostility. “Please don’t out me in class,” he added.

As Jon Shields and Joshua Dunn wrote in their 2016 book, Passing on the Right, younger conservative professors sometimes describe their plight in the language of gay rights. Like closeted homosexuals, they frequently disguise their identities and play along with the majority—at least until they get tenure, when they’re more likely to express their true selves.

Conservative students don’t have the same freedom. Like the Bryn Mawr student who was flamed on social media after she sought a ride to a 2016 Trump rally—so brutally that she withdrew from school—my Trump-supporting students are understandably afraid that they’ll be vilified by their peers.

Others feel maligned or threatened by their professors, almost all of whom are opposed to the president. So am I. Precisely because I dislike Trump, however, I think it’s my duty to talk with—and learn from—people who disagree with me.

And that’s where I disagree with many of my colleagues, who seem perfectly content to let pro-Trump students stew on the sidelines. Recently, at a faculty meeting at my school, we were asked what we’d do if a Trump supporter said she didn’t feel comfortable expressing her views in class on immigration.

“Why should she feel comfortable?” one professor asked. The people we really need to worry about, another faculty member added, are immigrants and students of color, whose “humanity” is under assault every day.

But insulating our classrooms from pro-Trump sentiment condescends to our minority students, all in the guise of protecting them. They already know that Trump’s election unleashed ugly outbursts of bigotry cross the country. Trump himself has made dozens of highly offensive remarks about racial minorities, women, and the disabled. I understand why our minority students would be skeptical about people who voted for him.

But it’s cynical and prejudicial to assume that every Trump voter is a racist or a misogynist. And, like every prejudice, it’s borne of ignorance: We don’t talk to each other, so we don’t know about each other either. Since the 1970s, as Bill Bishop detailed in his 2009 book The Big Sort, a declining fraction of Americans have reported conversations with people of a different political perspective. And people with more education are even less likely to engage in discussions across the political aisle.

That’s the ultimate indictment of our universities, which should expose us to ideas and people outside of our personal experience. And it underscores the unmet vision of affirmative action, which was designed to help students “learn from their differences” and “stimulate one another to re-examine even their most deeply held assumptions about themselves and their world,” as former Princeton President William G. Bowen wrote decades ago.

Bowen’s comment was cited approvingly by Justice Lewis G. Powell in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the landmark 1978 Supreme Court case upholding affirmative action. Drawing again from Bowen, Powell quoted a Princeton graduate who noted that students “do not learn very much when they are surrounded only by the likes of themselves.”

That’s exactly right. And that’s why I hope the federal district court in Boston upholds Harvard’s affirmative action system. But in the same spirit, I also hope we’ll make a concerted effort to insure that all of our students can say what they think once they get here. That means encouraging our Trump supporters to speak up in class (without outing them against their will, of course). And it means insisting that the rest of us grant them a respectful hearing, no matter what we think of Trump.

You can’t support race-conscious admissions, as a way to widen the conversation, then restrict the conversation to people who agree with you. That makes a mockery of affirmative action, and of the university itself. Students need to hear a broad array of voices, so they can learn from their differences. And they won’t learn very much if they are surrounded only by people like themselves.

Seven thousand Central American migrants are traveling toward the United States. President Trump wants Mexico to stop them. “I must, in the strongest of terms, ask Mexico to stop this onslaught.” Trump tweeted on October 18, when the “caravan” of mainly Honduran, El Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Nicaraguan migrants arrived at the Suchiate River on Mexico’s southern border. “Sadly, it looks like Mexico’s Police and Military are unable to stop the Caravan heading to the Southern Border of the United States. Criminals and unknown Middle Easterners are mixed in,” he tweeted on Monday.

Trump has often suggested Mexico should help the U.S. halt Central American migration. In early September, the Trump administration announced that it would give $20 million for bus and airplane fare to deport 17,000 undocumented Central Americans from Mexico. (Mexico refused the funds.) Last week, Trump revived a request that Mexico agree to a law similar to the European Union’s policy that migrants apply for asylum in the first “safe” country they arrive in: Central Americans bound for the United States would have to seek asylum in Mexico instead, although violence there is at an all-time high.

In reality, Mexico has been serving as the United States’ militarized buffer zone for some time—in no small part due to concerted efforts by U.S. administrations. Since 2014, the United States has spent nearly $200 million expanding a deportation regime in Mexico that has expelled over 600,000 migrants, mostly to the Northern Triangle countries—Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—but also to South America, Africa, and Central Asia. The arrangement has allowed both the Trump and Obama administrations to outsource their dirtiest work onto Mexico, deploying U.S. immigration officials and U.S. equipment throughout the country to help carry it out.

Mexico’s transformation into a full-fledged deportation state began in the summer of 2014.Mexico’s transformation into a full-fledged deportation state began in the summer of 2014. A large number of unaccompanied Central American children—over 68,000 in twelve months—arrived on the U.S.-Mexico border—and the Obama administration moved swiftly with Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto to approve a $100 million plan, known as the Programa Frontera Sur, that would protect “the safety and rights” of Central American migrants and secure Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala. “Both governments deny that the U.S. leaned on Mexico to crack down,” said Adam Isaacson, a Mexico security expert at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), but “in our view, it’s completely what happened.”

The reality of Programa Frontera Sur differed strikingly from its stated mission of protecting migrants. Programa Frontera Sur paid for advanced border control machinery—drones and security cameras, fences and floodlights, alarm systems and motion detectors—and the expansion of a controversial national immigration service known as Grupos Beta. The organization is tasked with providing water, first aid, and directions to migrants. But Grupos Beta workers—who stand out against the wilderness in neon orange t-shirts—have been known to extort cash from migrants and report them to immigration officials who detain and deport them. Cargo trains, known as “the Beast,” that Central American migrants rode atop on their journey north were sped up so that migrants could no longer jump onboard, forcing them to forge routes through the forests of Chiapas and Oaxaca—where they are frequently attacked and robbed. Valeria Luiselli, a celebrated Mexican writer, described Programa Frontera Sur as an “augmented-reality video game,” where “the player who hunts down the most migrants wins.”

With Programa Frontera Sur, the United States extended its reach deep into Mexico’s interior. U.S. Border Patrol agents were dispatched to train immigration agents throughout Mexico’s 58 detention centers. In April, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security expanded an $88 million program for biometric equipment at Mexico’s southern border checkpoints that shares the fingerprints, iris scans, and descriptions of scars and tattoos with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Another $75 million from the United States went towards building communications towers along the remote Guatemala border. “The entire country of Mexico is now a border,” one Mexican analyst declared.

By one measure, Programa Frontera Sur achieved its intended outcome. Since 2014, Mexico has deported more Central Americans each year than the United States—nearly 180,000 in 2015. (For comparison, the top-deporting country in the EU, Greece, deported only around 105,000 migrants in 2015, at the height of Europe’s migrant crisis.) Now the United States seems to be building on the model. Throughout 2018, reports surfaced of Mexican immigration agents in the northern Mexican border cities of Tijuana and Nogales receiving orders from U.S. Border Patrol to detain and deport Central American migrants, despite their legal right to apply for asylum in the United States. “It’s a collaborative program that we’re doing with the Americans,” a Mexican immigration official told a Texas immigration lawyer in July.

But the militarization hasn’t changed the underlying dynamics driving immigration: El Salvador and Honduras rank as the second and fourth most violent countries in the world, respectively, and Guatemala trails not far behind. As a result, immigration from the so-called Northern Triangle countries has risen even as the number of Mexicans immigrating to the U.S. has declined. Maureen Meyer, a Mexico expert at WOLA, estimates that 400,000 Central Americans pass through Mexico in any given year. Parents continue to send their children north because the dangers of staying outweigh those of leaving.

Mexico, too, wants Central American immigrants out. A 2014 study found that many Mexicans discriminate against Central Americans, who live in Mexico’s most dangerous neighborhoods and work low-wage jobs that Mexicans avoid. Migrant shelter workers told WOLA in one survey that they have extracted pellets out of migrants’ legs after Mexican immigration agents shot at them with pellet guns. The same report cited migrant testimonies that immigration agents also use electric shock devices, despite laws prohibiting the use of all weapons. The Mexican media often frames Central Americans as gangsters, even though only eight of the 21,000 migrants scanned last year with biometric equipment were identified as gang members.

These factors create a harrowing ordeal for those fleeing violence in their home countries. Women are particularly vulnerable. An estimated eight in 10 migrant women and girls are raped while traveling through Mexico. Many reportedly bring birth control as a precaution.

Mexico has repeatedly and adamantly refused to pay a cent for Trump’s wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. But in many ways, Mexico has long been paying for a wall—on its southern border, instead. Since 2014, a vast and sophisticated deportation apparatus has emerged in Mexico that has traumatized and harmed hundreds of thousands of people. Although U.S. assistance only accounts for about 2 percent of Mexico’s $10 billion annual defense budget, much of the new infrastructure would not exist if it weren’t for the United States persistently nudging Mexico to crack down. There are parallels here with how rich Western European countries like Germany and France have relied on poorer countries in southeastern Europe and North Africa to halt the flow of migrants coming from Syria, Afghanistan, Mali, and Guinea.

On October 3, President Trump called Mexico’s president-elect, the charismatic leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador, to discuss among other things how to halt Central American migration. López Obrador said he planned to plant two and a half million acres of timber and fruit trees in southern Mexico and build a high-speed “Maya” tourist train linking the temples of Palenque to the pyramids of the Yucatan: Creating jobs for Central American migrants will keep them from the United States, López Obrador believes. “Great phone call,” Trump tweeted approvingly afterwards.

López Obrador, who will succeed the deeply unpopular Peña Nieto on December 1, could present a threat to Trump’s deportation agenda. A pacifist and anti-imperialist nationalist, López Obrador has repeatedly expressed disdain for Programa Frontera Sur—and promised to focus on “addressing the root causes of Central American migration.”

“We are not going to chase migrants. We are not going to criminalize them,” Alejandro Encinas, the incoming undersecretary of immigration, recently told The Washington Post. López Obrador’s incoming cabinet has said that it would not cooperate with U.S. requests for the policy that would require Central Americans to seek asylum in Mexico rather than the United States.

Pressing for jobs, not pellet guns, departs radically from prior approaches. López Obrador’s immigration agenda remains vague, and many doubt that he will entirely dismantle Programa Frontera Sur or open the southern border to Central American migrants. Come December, both countries will find out how serious the new Mexican president is.

No comments :

Post a Comment