Last week Donna Strickland, an associate professor at the

University of Waterloo, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. She is the third woman

to be awarded the prize in its history—Marie Curie received it in 1903 and

Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963—but as recently as last May, Wikipedia rejected a

draft page about Strickland on the grounds that she did not meet “notability

guidelines.” The work for which she received the Nobel—generating the “shortest

and most intense laser pulses ever created by mankind,” according to the prize

committee—is over 30 years old. She published the groundbreaking paper, with

co-authors and now co–Nobel winners Gerard Mourou and Arthur Ashkin, in 1985. Between

then and now she has won many prizes, but it took a Nobel for her to become

Wikipedia-worthy.

On the same day that Strickland became a Nobel laureate and Wikipedia’s editors quickly threw together a page about her, President Donald Trump used a rally in Mississippi to ridicule Christine Blasey Ford, the psychologist who testified of her assault at the hands of Brett Kavanaugh, who has since been sworn in as a Supreme Court justice. Trump’s words were cruel. He elicited laughter at Ford’s expense, making her trauma—and that of all sexual assault survivors—into the stuff of jokes. The president’s ridicule turned on the idea of Ford’s ignorance: “How did you get home? I don’t remember. How’d you get there? I don’t remember. Where is the place? I don’t remember. How many years ago was it? I don’t know,” said Trump. “I don’t know, I don’t know. What neighborhood was it in? I don’t know. Where’s the house? I don’t know.”

These two events—a woman dragged from obscurity in the morning, belatedly recognized for her achievements; and a woman scorned in the evening, her memory deemed fallible, faulty—are connected. Their stories are part of the same, long history of undermining women’s epistemological authority, of doubting and denying their very ability to know. Wikipedia, which is largely overseen by male editors, rejected Strickland because she was not noteworthy enough to be accepted into the ranks of scientists who have unique insight into how the universe works—until, of course, she became excessively noteworthy for just that. Republicans rejected Ford not because they thought she was lying per se, but because they decided she must be misremembering the assault—that Kavanaugh’s memory is accurate but Ford’s is faulty, that between the two it is the woman’s mind that failed, that she with her explication of the neuroscience of trauma and not he with his adolescent calendars fell short of their criteria for knowing. (And all of this despite the fact that he was the drinker.)

Only around 17 percent of profiles on Wikipedia are of women, a problem with roots in the history of the encyclopedia itself. The great Encyclopédie of the French Enlightenment included the contributions of around 150 men—and not a single woman. The first version of Encyclopedia Britannica in the 18th century featured 39 pages on curing diseases in horses and three words on woman: “female of man.” On the surface, Wikipedia’s bias appears to stem from the fact that only around 10 percent of editors are female. But the problem goes much deeper—to the aggressiveness with which male editors and administrators delete pages on women and harass female editors who try to change this. They get called “cunts” and “feminazis”; they have had fake, pornographic images of them posted online. To avoid harassment, some women have resorted to using gender-neutral pseudonyms so male editors can’t identify them as female. Others simply quit.

“Wikipedia is probably the best example of the appropriation of human value in masculinist terms,” says Gina Walker, an intellectual historian and professor of women’s studies at The New School.

The problem—the marginalization of women as a force in history—extends to textbooks and educational curricula across the world. In 1971, research on women in U.S. high school history books found that more space was dedicated to the length of women’s skirts than to the suffrage movement. That spurred a campaign by textbook publishers and educational associations to correct the bias. Universities created “women’s studies” programs and offered courses on “women writers.” But this has often meant that women are put in a “women’s canon,” secondary and lesser to The Canon, which is meant to be human but is really male. When women are recognized alongside men, they are exceptions and anomalies.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, educational reforms stalled the campaign of the previous two decades. In many states, it has regressed. Last month, for example, the Texas Board of Education voted to remove Helen Keller and Hillary Clinton from the social studies curriculum.

At The New School, Walker is leading a project called “The New Historia,” which aims to counteract this trend by creating a database to document and promote history’s forgotten women. There’s Diotima, who appears in Plato’s Symposium as Socrates’s teacher. That she was a historical person—a priestess of Mantinea—did not come into question until the 15th century, when the Renaissance scholar Marsilio Ficino, certain that a woman could not have been an acclaimed philosopher, asserted that she must have been a figment of Plato’s imagination, a rhetorical device created for the purposes of the dialogue. That would make her, oddly, Plato’s only fictitious character. Yet scholars since have continued to work under the assumption that Diotima never really existed.

There’s Émilie du Châtelet, the 18th-century philosopher and mathematician, whose translation of and commentary on Newton’s Principia advanced the scientific revolution in France. New scholarship suggests that the great Encyclopédie included entries taken directly from Institutions de Physique, her philosophical magnum opus—that she had, in fact, helped frame the very questions the Encyclopédie sought to answer. That means there was a female encyclopédiste among the male contributors after all, though she never received attribution.

“Women are profoundly ignorant of their female legacy,” says Walker. “If we don’t know it, how are men and boys going to know it?”

The impulse to “recover” lost women is not a new one. In 1803, Mary Hays, a disciple of Mary Wollstonecraft, published Female Biography: or Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries, a six-volume compendium. Feminist scholars have been recovering the achievements of women—Laura Bassi, Ada Lovelace, Hedy Lamarr—ever since. But because they are rarely integrated into textbooks and syllabi, they become recurrent subjects of recovery.

“Women’s biographies cannot simply be recovered because once they are produced they no longer fit into the existing understandings of histories and course curricula that have been designed in their absence,” says Walker.

Walker envisions moving past this cycle of remembering and forgetting to, indeed, a new history. The goal is not simply to show that women have been part of the work all along, despite their exclusion from official cultures of learning and knowledge-production; it is to restore women’s epistemological authority, to keep contemporary women like Strickland from being ignored and requiring recovery centuries hence.

How would the restoration of that authority reverberate in the wider world? If Americans learned about women who deployed power, who were historical and intellectual forces, who knew, would that change their reception of women’s knowledge and women’s voices? Perhaps they would have an easier time accepting women in positions of authority. Perhaps women’s voices wouldn’t be so breezily dismissed. Perhaps Hillary would have won, says Walker. And perhaps what Christine Blasey Ford knew would have mattered.

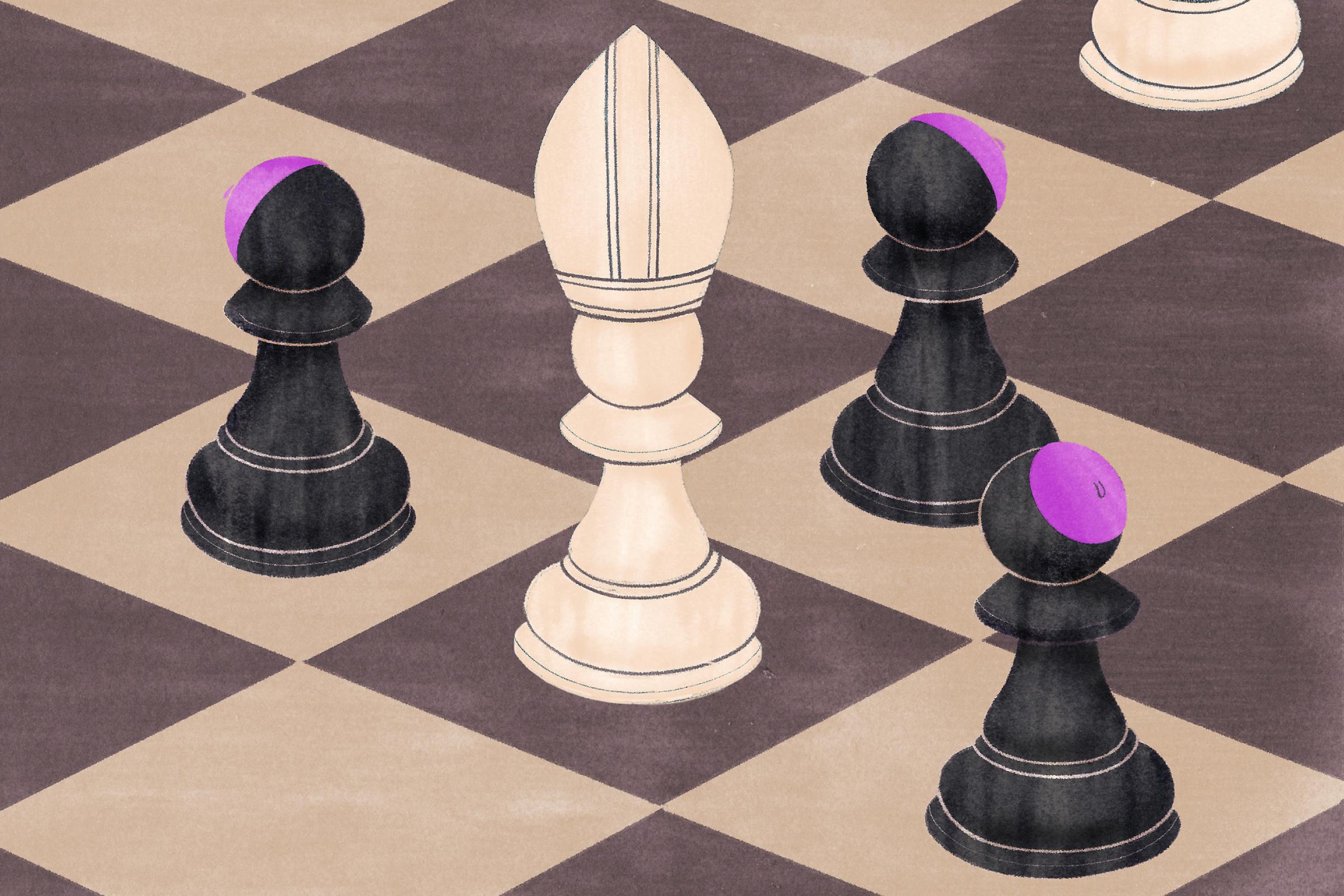

In August, in a letter published in the National Catholic Register, Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò blamed the Roman Catholic Church’s sexual abuse crisis on gay priests who “act under the concealment of secrecy and lies with the power of octopus tentacles, and strangle innocent victims and priestly vocations, and are strangling the entire church.” Pope Francis, he wrote, had sheltered such priests. Viganò specifically named Theodore McCarrick, a “serial predator” who resigned as a cardinal in July after the news broke that he’d sexually abused adolescent boys while rising to become one of America’s most prominent archbishops. Viganò called on Francis to “set a good example” and resign, along with the other cardinals and bishops implicated in the scandal. He wrote little about the fact that McCarrick’s abuse took place during the papacies of Francis’s conservative predecessors, John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Whatever Francis knew about McCarrick, the previous popes likely knew more. But their complicity was overlooked.

Viganò belongs to a traditionalist wing of the church that has never truly accepted Pope Francis. In the United States, this contingent includes Cardinal Raymond Burke of St. Louis, San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone, and Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput. These powerful clergymen aren’t just conservative on theological matters, but in their politics as well. While serving as the Vatican’s apostolic nuncio, or ambassador, to Washington, Viganò was responsible for introducing Pope Francis to Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who refused to grant marriage licenses to gay couples in 2015. From San Francisco, Cordileone publicly supported California’s Proposition 8, which opposed same-sex marriage, raising over $1 million to get it on the ballot. Chaput has called on the University of Notre Dame to give President Donald Trump an honorary degree. And Burke plans to partner with former Trump campaign chief Steve Bannon to construct a Catholic compound near Rome that will host meetings and seminars with church leaders and politicians interested in protecting “Christendom.”

In late August, several conservative American bishops and their allies published letters in support of Viganò, even after journalists from The Washington Post and The New York Times reported that he had likely exaggerated many of the claims he made in the Register. They are using the worst crimes of the church to attack Francis and his liberal policies. What should have served as a reckoning has been transformed into an opportunity to take him down.

Francis has been fighting off critics practically since the day he was elected in 2013. When Benedict, a Bavarian theologian nicknamed “God’s Rottweiler,” stepped down earlier that year, he still had significant support in the Vatican for his most extreme conservative stances—he once quoted fourteenth-century texts that criticized Islam as “evil and inhuman”; lifted the excommunication of a British bishop who denied the Holocaust; and claimed condoms worsened the fight against AIDS. Since then, conservative dissenters in the Catholic hierarchy have formed a resistance of sorts, pushing back against Francis’s pronouncements on divorce, immigration, climate change, and poverty.

What should have served as a reckoning for the church has been transformed into an opportunity to take Francis down.Much of this resistance comes from the United States. Although 63 percent of American Catholics support the pope, according to a recent CNN poll, conservative clergy and wealthy Catholic donors remain among his fiercest critics. Their most common line of attack focuses on Francis’s supposed support for gay priests. In 2013, the pope quipped, “Who am I to judge?” when asked about gay Catholics. Two years later, he met with an openly gay former student, Yayo Grassi, and his partner in Washington. And more recently, he asked James Martin, a Jesuit priest who has written a book on LGBT Catholics, to deliver a talk at the World Meeting of Families in Ireland this past summer. Francis has actually taken no official action to change church policy about homosexuality, but conservatives have still reacted in horror. In May, when Francis told a gay Chilean sexual abuse survivor that God made him gay and loves him anyway, American Conservative columnist Rod Dreher said the pope was destroying the church like a “wrecking ball.” Conservatives like Dreher maintain that gay priests are the main perpetrators of child sexual abuse, and that their powerful supporters within the Vatican—whom Dreher calls the “lavender mafia”—are responsible for harboring them.

Of course, there is no evidence of a higher rate of abuse among gay clergy; in fact, abuse, religious and secular, is most commonly the result of “situational generalists” who abuse whoever is in their control, male or female, children or adults. But that hasn’t stopped conservatives from arguing that gay men are responsible for the abuse crisis. In his letter, for example, Viganò uses the word “child” twice; “homosexual” appears 16 times. Cardinal Burke compared gay priests to murderers in a 2015 interview with LifeSite News, a pro-life web site. The problems the church faces, from child abuse to a lack of men applying to the priesthood, he once said, are because it has become too “feminized,” which, given Burke’s track record, could be taken as a way of saying “too gay.”

The conservatives attempting to blame gay priests for sexual scandals appear to have two main objectives. First, they hope to purge the church of its gay clergy. And second, they want Francis out. Because he has softened the church’s stance on LGBT issues, his opponents can accuse him of sheltering gay priests and, in their minds, saddle him with responsibility for the sexual abuse crisis, despite the fact that it began long before he was elected pope.

No one yet knows how much Francis knew about the abuse. On the papal plane hours after Viganò’s letter was released, he did not deny the charges leveled at him. Instead he told journalists on board, “You have the journalistic capacity to draw your own conclusions.” A strong denial would have been preferable, under the circumstances—he was traveling back to Rome from Ireland, where he had just met with victims of sexual abuse there, which reached such a horrific scale that an entire generation of people had left the church. The pope later said the meeting left a “profound mark” on him. Presented with the letter so soon after seeing the traumatized victims, he may simply have been too shaken to answer. Or it could mean that Francis did know about McCarrick. He has been pope for five years. He could have taken a stronger stance against sexual abuse in the church already. He still can.

But amid this muddled, internecine conflict, one thing is clear: Conservative attempts to tear Francis down, while absolving his predecessors and blaming a global sexual crisis on gay priests, are sinister and abusive. The problems of the Catholic Church stem not from homosexuality but from an entrenched culture that protects clergy—and the church itself—at the expense of the people they are meant to serve. Long ago, the Vatican and its leadership lost their connection to the ordinary lives of the billion Catholics worldwide. Now, they privilege reputation above truth, and, like many of the current accusations flying around, that instinct is rotten.

Last week, Peru’s supreme court overturned the pardon of brutal Peruvian ex-President Alberto Fujimori, tossing the leader back to his 25-year prison sentence for human rights violations and corruption. Human rights groups, outraged when Fujimori was pardoned by former-President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski on Christmas Eve last year, reportedly as part of a backroom deal to save his doomed presidency, are understandably ecstatic. Yet as the reversal is welcomed by Amnesty International, and splashed across international headlines, one of Fujimori’s less-discussed and most appalling legacies is still missing from the conversation: the over 200,000 indigenous women who were forcibly sterilized under his regime.

María Mamérita Mestanza Chávez was 33 when Peruvian health officials began threatening her with jail if she did not submit to surgical sterilization, according to those presenting her case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1999. Mestanza was a low-income, illiterate indigenous woman, and when after numerous intimidating visits she finally agreed to tubal litigation, she wasn’t informed of the risks, nor was she examined for potential complications. Her husband contacted doctors shortly after the surgery, concerned that his wife wasn’t well, and was told it was simply the effects of the anaesthesia wearing off. Mestanza died at home nine days later.

Fujimori gained international support and USAID funding for the sterilizations by presenting them at the UN Beijing Conference on Women in 1995 as part of a progressive reproductive rights program—a classic case of ethnic cleansing masked in “development” rhetoric. The number of those sterilized under Fujimori’s so-called “family planning” program between 1996 and 2000 is estimated at 294,032 people, including 22,004 men, by Peru’s official human rights watchdog Defensoría del Pueblo. Other estimates are even higher.

Mestanza’s case ended with an $80,000 payment by the Peruvian state and a promise to “conduct administrative and criminal investigations.” The petitioners, in the words of the settlement document in 2003, made clear that this was only one example of a “systematic government policy to stress sterilization as a means for rapidly altering the reproductive behavior of the population, especially poor, Indian, and rural women.”

The available estimates for the sterilization campaign would make it one of the biggest such programs since Nazi Germany. Why does it receive so little attention?Yet despite the fact that this case and the ensuing investigation played out alongside the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) that followed the collapse of the Fujimori regime, not one mention of forced sterilizations is to be found in the commission’s public report. The CVR’s broad mandate allowed it to cover two decades, three presidents, two Maoist terrorist groups, and several distinct instances of state-backed violence—both before and during Fujimori’s time. But the commissioners decided to leave the sterilizations out, claiming they were tangential to the period of violence, even while including other tangential crimes with higher stakes for Peruvian elites—such as Fujimori’s embezzlement scandal. While individual cases have been opened and re-opened by various investigations, the Peruvian government has repeatedly denied the existence of systematic forced sterilization.

Meanwhile, many more victims’ stories have emerged. In 2013, the interactive Quipu project began enabling women to call in and share their stories via telephone, building an online oral history. Yet these women’s stories were still nowhere to be found in this week’s headlines, even in write-ups of the court decision that mentioned other Fujimori-era atrocities. On a superficial level, this is because Fujimori was only formally convicted for embezzlement, bribery, authorizing death squads and rigging elections—as per the major crimes outlined in the truth commission. But at the same time, the available estimates for the sterilization campaign would make it one of the biggest such programs since Nazi Germany. Why does it receive so little attention?

Spanish colonial rule not only guaranteed sickness and death for many indigenous Peruvians, but created the fragmented and divided structures that continue to exist in Peruvian society today. That includes the geographical divide between the coastal region—predominantly urban, white and Spanish speaking—and the highlands—mostly rural, indigenous and Quechua or Aymara-speaking, not to mention the rainforest where 10 percent of the Peruvian population lives and over 17 languages are in danger of extinction. Indigenous peoples in the highlands and the Amazon are still in many ways second-class citizens, without the political and economic capital of their white and mestizo counterparts on the coast—their languages, voices and lives are disposable in the eyes of the state.

Fujimori’s sterilization campaign, which didn’t come to international attention until hundreds of thousands of indigenous and primarily Quechua-speaking women had been forced into tubal ligations, is one of several cases highlighting the indigenous populations’ disposability in Peru. In the 1980s, tens of thousands of indigenous peoples in Ayacucho were massacred by the Shining Path and the Revolutionary Movement of Tupác Amaru, two Maoist terrorist groups that grew their base in the Quechua highlands. The massacres went unnoticed by the Peruvian state for years—and many innocent indigenous people were subsequently caught in crossfire and killed by the Peruvian military itself.

Political amnesia has consequences—ones Fujimori and his political party have profited from time and time again. Peruvian journalist César Hildebrandt has gone so far as to refer to a “Peruvian Alzheimer’s” going back to the 1990s, when Fujimori consolidated support through the false claim that he was responsible for capturing Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán—even though the counterterrorism directorate police force that carried out the operation was not under his supervision. Collective misremembering of 90s-era crimes has also allowed for Fujimorismo, the political ideology and personality cult built around Fujimori and his family that includes his daughter’s Fuerza Popular party, to grow. Since Fujimori’s initial arrest and sentencing in 2009, his daughter Keiko’s party has gained the majority in congress—through a system that was constitutionally drafted by her father—and nearly won the presidency in 2016.

Keiko became first lady in the ’90s after Fujimori’s wife and Keiko’s mother, who says she was tortured by Fujimori for denouncing him, was stripped of the title. Keiko has repeatedly downplayed her father’s human rights violations, and this week expressed sorrow over his jailing. She intends to run for presidency again in the 2021 general elections.

Over the past decade, Peruvian politicians such as former President Alan García have framed attempts to resurface the atrocities of the Fujimori regime as pointlessly dwelling on sins of the past. This has led, for example, to García initially rejecting funds from the German government to build a museum focused on the era of terrorism and dictatorship. The reality, however, is that addressing the systemic oppression of Fujimori’s regime is vital to understanding the political systems that allowed for such atrocities to occur—under a party that remains the congressional majority in Peru.

The over 200,000 women who were violated under Fujimori have been treated as, at best, an afterthought for the past two decades. As the world becomes more aware of the perils of ignoring women’s stories, and as another Fujimori gears up for a presidential bid in 2021, there’s every reason to start listening to them.

No comments :

Post a Comment