The search giant today announced Project Stream, a "technical test" which lets you stream video games to the Chrome web browser on either a desktop or laptop.

The search giant today announced Project Stream, a "technical test" which lets you stream video games to the Chrome web browser on either a desktop or laptop. Though USB Type-C is a universal charging and docking standard, Microsoft left this key connection off of its Surface Pro 6 and Surface Laptop 2.

Though USB Type-C is a universal charging and docking standard, Microsoft left this key connection off of its Surface Pro 6 and Surface Laptop 2.

The setting is a pharmaceutical trial of a psychiatric medication. The trial room is like the inside of a spaceship from the 1970s. From the other side of a purple-lit window, a beautiful young scientist in aviator eyeglasses intones, “Subjects, take your pills.” Owen Milgrim (Jonah Hill), a kindly schizophrenic, and Annie Landsberg (Emma Stone), a smart slacker traumatized by her sister’s death, gulp them down.

This scene comes in the thick of Maniac, a new ten-part Netflix series from director Cary Joji Fukunaga (Sin Nombre, True Detective). The season takes a good four episodes to get going, but from there it opens up like a flower. Set in an alternate but contemporary universe where analog technology still rules the day, Maniac is much more like a long, episodic movie than a television show. In its hallucinatory stylings it recalls The Science of Sleep (2006) or Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). Like those movies, Maniac takes place largely inside the dreamed worlds of its protagonists, controlled by the drugs they take to see if a damaged mind can be healed. The result is a TV show which perhaps does not treat mental illness very scientifically, but achieves real catharsis by pushing its leads down a road of psychological transformation.

Maniac plays heavily on its analog premise. A person short on cash, for example, can raise money by being advertised to in real life: An “Ad Buddy” shows up to read you a script on what product to buy. But the “real” world is mostly a place to establish Owen and Annie’s motivations to become lab rats: Owen’s in it for the money, while Annie has blackmailed her way in because she’s already addicted to one of the trial’s drugs. Owen’s family is a horrible identikit set of WASPs, while Annie is unemployed and lonely, unable to put together her life after the terrible car accident that killed her sister and that she blames on herself.

Michele K. Short / Netflix

Michele K. Short / NetflixIn contrast, the science lab where they enter the drug trial is a gorgeous funland of actual maniacs. Justin Theroux plays Dr. James Mantleray, a deranged researcher with a complicated relationship with his mom, a celebrity therapist played by Sally Field. She helps people across America talk through their problems; he hates his mother and wants to fix the world’s problems with pills. His partner in science and troubled romance is the aforementioned beauty in aviators, Dr. Azumi Fujita, played by Sonoya Mizuno (Ex Machina). These two form a sort of mirror relationship to Owen and Annie, but they are without doubt the truly “mad” ones of the show.

The show’s narrative divides into the three stages of the drug trial, which consists of drugs named A, B, and C. In sequence, each pill forces the subjects into unconscious reveries, which we see played out as action. Drug A makes the subjects rehearse their trauma. Drug B takes them through a series of “reflections” that explore their emotional architecture through fantastical plots. Drug C prompts “confrontation,” which supposedly helps the subjects to break through their psychological strictures. Through it all, the subjects are both guided and analyzed by a very large mainframe computer nicknamed “Gertie.” The problem with Gertie is that she has been programmed to feel empathy—and therefore, like the humans she is monitoring, she runs into her own emotional crisis, and mismanages the trial.

The other big problem is that Owen and Annie keep being drawn into each other’s “reveries.” In one plot they show up as a couple named Bruce and Linda, on a quest to return a lemur named Wendy to its rightful owner. Then they are glamorous 1940s aristocrats, hunting a lost chapter of Don Quixote at a séance. Sometimes they lose each other. Owen has to endure his family becoming a shockingly violent mob gang without Annie as his companion. Annie embarks alone on a Lord of the Rings–style journey to transport her sister to a healing lake. In the strangest of all the reveries, Owen becomes a Swedish man named Snorri who accidentally kills an alien.

Michele K. Short / Netflix

Michele K. Short / NetflixThe reveries are entertaining vignettes, like little movies within a TV show. But they also offer an interesting meditation on narrative itself. Owen’s chief psychiatric problem is that he sees patterns where they don’t exist. Television does the same thing: The world is really just chaos, not a self-contained story. But because the reveries take place inside the minds of Owen and Annie, they possess a narrative neatness that is psychologically realistic, rather than artistically so. They’re dreams, not plots.

The show hinges entirely on Owen and Annie’s relationship, which is a friendship, not a romance. Hill and Stone have worked together before, in 2007’s Superbad, but the pair have truly unusual chemistry here. By the end of the show, their friendship has formed a third entity, a psychological bond with a potential healing power. Interpersonal communication is not a cure-all fix in Maniac, but real empathy—poor Gertie’s errant programming notwithstanding—is the only thing that can hoist Annie and Owen out of their self-destructive trajectories.

Maniac is the rare series that plays with reality without alienating the viewer emotionally. It’s not really about madness at all, and that just about excuses its fast and loose treatment of schizophrenia and grief—which are, after all, just boring old parts of our world. Instead it’s about stories: the ones we tell ourselves about who we are, the ones that compose the industry of therapy and psychiatric treatment, and the ones that we make in partnership with the people we meet in life.

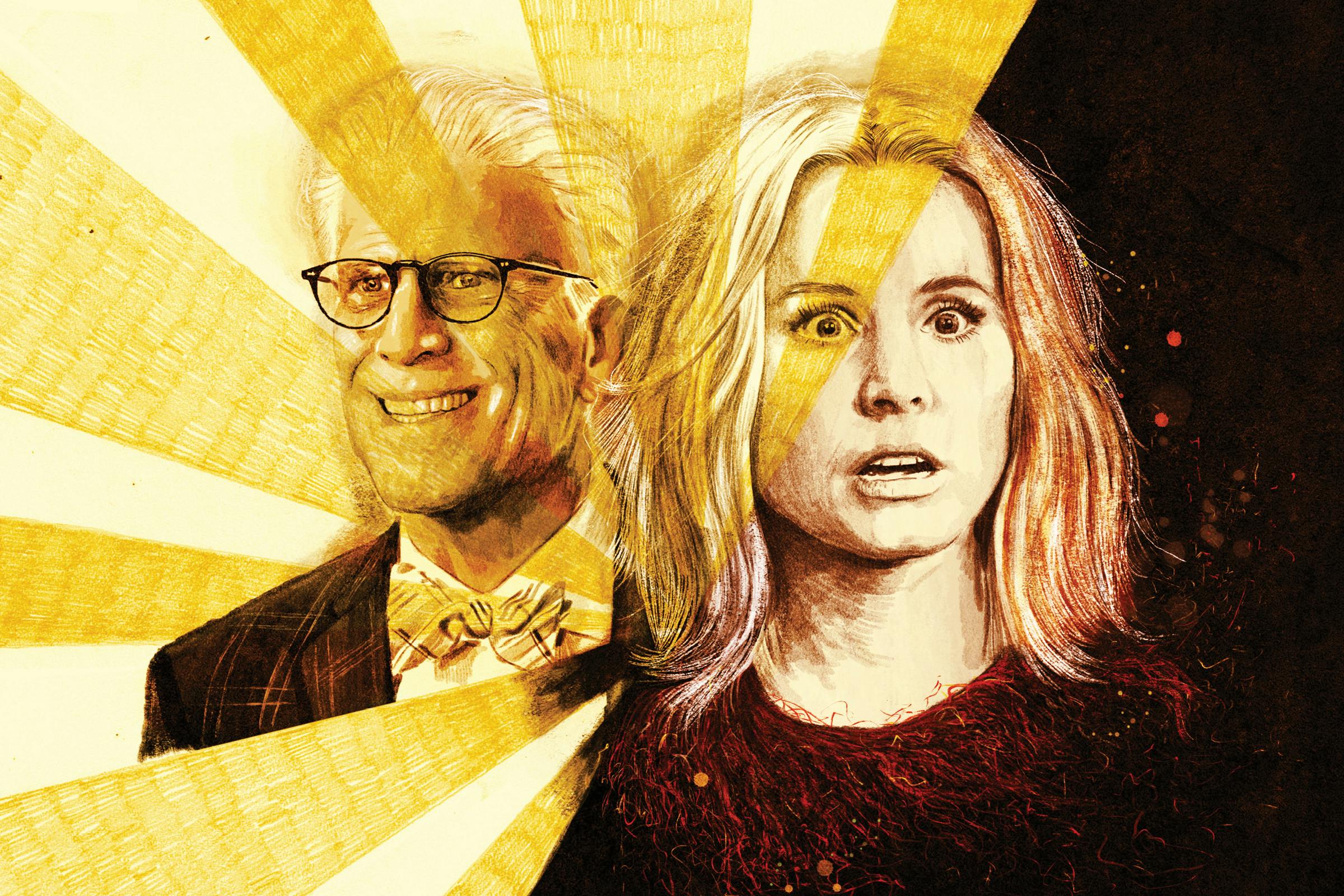

The Good Place is a show set in a special new corner of hell. The person in charge, an insubordinate demon named Michael (Ted Danson), is undergoing a crisis: For thousands of years, he was a loyal employee of the inferno, known in the show as “The Bad Place.” He specialized in torturing sinners the old-fashioned way—stuffing hot dogs into their orifices, melting down their eyeballs, tearing off their fingernails. Then, somewhere along the way, he got bored.

He wanted to disrupt the damnation business, to innovate. He convinced his boss, Shawn (Marc Evan Jackson), to give him one crack at a bold experiment. What if he took four sinners headed for punishment, and dropped them instead into a squeaky clean, candy-colored small town, telling them it was heaven (aka The Good Place)? To make it more interesting, the four people would be marginal moral cases—not murderers, just narcissists and jerks whose specific flaws would grate on one another to the point that living in the same neighborhood for all time would feel like torture. Michael believes that if this pilot program goes well, he will have created an entirely new model for eternal, self-sustaining suffering.

For the first season, neither the four test subjects nor the audience knows about this scheme. When the show opens, Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell) finds herself sitting on a sofa in a waiting room, across from a wall sign that reads “Welcome! Everything Is Fine.” Michael calls her into his office, presents himself as a kind of friendly guardian angel, and tells her not to fear: She has reached the promised land, where nobody suffers and the supply of frozen yogurt is limitless. This news confuses her. She is not shocked to find that she is dead. But she is shocked to have landed in The Good Place.

In life, Eleanor was not only not a saint, but actively amoral, a self-professed “trash bag” who lied, manipulated, and once sold thousands of dollars’ worth of T-shirts that mocked her roommate. When Michael tells her that she tipped the karmic scales with her humanitarian work, she immediately realizes that there has been a clerical error. She’s an interloper in the afterlife. But it takes her and the three other humans living in a fake paradise an entire season to uncover the truth.

Her light bulb moment in the first season finale, when she guesses that they are in fact in The Bad Place—and that their other neighbors are demons in disguise—is still one of the most unexpected and satisfying twists I’ve ever seen outside of a true crime drama. The Good Place plays with time and structure like no other comedy on television; it is not afraid to tear apart its own premise and start over. Season 3, which airs on NBC this fall, may be its most ambitious reset yet, as it switches from the cosmic settings of heaven and hell to the real world, confronting the potential for bliss and pain in the here and now. For a show that started out with a fantastical idea, this is a risk. The road to spiritual redemption lies, this season insists, through the banal and the ordinary.

The creator of The Good Place, Michael Schur, is also the showrunner behind The Office and Parks and Recreation. With those two shows, Schur proved himself to be a master of the quotidian, adept at extracting the absurd and awkward from the everyday. Both were workplace comedies set in sleepy suburbs: a regional paper goods office in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and a municipal government headquarters in the fictional town of Pawnee, Indiana. Both relied on the mockumentary formula, in which an impartial camera crew records even the most low-stakes situations and each character’s intimate reactions to them. At the core of each show was something gooey and warm: an enduring love of humans, with all their flaws, for all their ego trips, and all their strange little tics and odors and mistakes.

You root for Schur’s characters; you want them to win. Amy Poehler’s Leslie Knope from Parks and Recreation, a blonde hummingbird with an irrepressible drive to get things done, begins the show as an overeager annoyance, but she finishes as a heroine, a woman on her way to high office. Even Michael Scott (Steve Carell), the hapless and often willfully offensive boss from The Office, earned the viewer’s fervent blessing by the show’s seventh season; he found love and made amends. We want these characters to be happy, because we see ourselves in them, and we want to be happy too.

In The Good Place, Schur envisions humanity against a grander backdrop. Gone are the roving camcorder and the drab trappings of the nine to five. The action takes place not under corporate fluorescent lights but in a marshmallow dream world. As in most Schurian comedies, its cast is an instantly lovable band of total weirdos. When Eleanor first tours The Good Place (which is really The Bad Place), she meets her assigned “soul mate,” Chidi Anagonye (William Jackson Harper), a bespectacled moral philosophy professor from Senegal, who finds simple decisions so difficult that choosing between a blueberry muffin and a bran muffin makes him cry. Then she meets Tahani Al-Jamil (Jameela Jamil), a tall, vain socialite in floral tea dresses who can’t stop name-dropping even in death.

At first, both Chidi and Tahani believe they belong in The Good Place, despite their clear shortcomings. It is only when Eleanor gets to know Tahani’s partner, Jason Mendoza (Manny Jacinto), that she starts to sense that not all may be as it seems. When Jason arrived in heaven, Michael explained to him that he made it in because he was a Buddhist monk who had taken a vow of silence, but Jason can only pretend to live up to his robes for so long. Eventually, he confesses his true identity to Eleanor. He was an EDM DJ who died trying to rob a Mexican restaurant. Eleanor then enlists Chidi in a secret process of tutoring the group in ethics, with the hope that they will all become the virtuous people Michael thinks they are before they get caught.

This first season meditated sweetly on how even degenerates can learn to act righteously if they band together; how communities are always stronger than individuals and can lift them up. It felt like a pleasant romp through a truly idiosyncratic setting, where at any time a character could call for Janet (D’Arcy Carden)—an all-knowing computer program in the form of a woman in a purple skirt suit—and she would appear, daffy and affable, able to produce any item on demand. It was all about bad people in a good world, striving to improve.

But it’s after the twist in season 2 that the show gets really exciting, as Michael realizes that his plan is futile. No matter what he does, the humans keep trying to be good. So he decides to switch sides. He secretly befriends his guinea pigs, and promises to help them get to the actual Good Place, via a portal in Bad Place headquarters. He too starts to reform, sitting in on their ethics classes, and grappling in one of the best episodes, “The Trolley Problem,” with a classic thought experiment: Should you steer a runaway trolley away from hitting five people if it means directly causing the death of one bystander? Either they all get to The Good Place, or none of them does.

What began as a show about sinners trying to bluff their way through heaven becomes the story of a posse of essentially goodhearted people, struggling to save themselves from the jaws of hell. This is where the Schur formula really kicks in. You start to root for Eleanor, despite her selfishness; for Chidi, despite his dallying; for Tahani, despite her narcissism; and for Jason, despite his folly. You even root for Michael. Their salvation becomes our salvation.

The show’s third season takes place not in heaven or hell, but in an even more surreal location: Earth. Michael has introduced the foursome to a cosmic judge (Maya Rudolph), who comes up with a plan to determine their fates. She gives the humans a chance to live again, to find out whether or not they can become good people if granted an extension. She snaps her fingers, and poof, they each return to the moments right before they died. Eleanor doesn’t get hit by that grocery cart. Tahani isn’t smashed by a golden statue at a gala. Jason doesn’t suffocate inside a safe during the restaurant heist. Chidi isn’t crushed by an air-conditioning unit.

The plan, according to the judge, is to see whether they will become noble on their own, without interventions. But of course they do get some help—from Michael and Janet, who bring them together in Australia to take part in a neuroscience trial. There, they all become colleagues at a university. It’s another experiment—in a more mundane, academic setting, but with stakes just as high as before. These episodes retain the punning humor of earlier seasons but lack many of the magical-realism elements, and fewer jokes are based on demons popping up unannounced (though a lairy demon named Trevor, played by Adam Scott, does briefly escape from The Bad Place to join the brain experiment).

Schur has in essence taken his otherworldly show and shrunk it back down to a banal workplace comedy. Eleanor, Chidi, Tahani, and Jason show up at an office every day, where we get to see how they act when they are unaware of the celestial consequences. With their memories of The Bad Place erased, they meet one another afresh and have no idea they’ve each been brought back from the dead. Yet we in the audience know what is at stake. We know that they are all fighting for redemption, even as they engage in petty squabbles and form unrequited crushes on one another. The Good Place was once a show about how to live better in the afterlife. Now, it is a show about how we can all live better in this one.

Some climate change activists oppose doom-and-gloom rhetoric. They know that, if we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly, the planet will soon become more habitable to flesh-eating bacteria than for human beings. But focusing too much on that risk promotes widespread hopelessness, they argue. And without hope, there will never be action.

This logic is understandable in principle, but feels increasingly deluded in practice. The Trump administration has all but dismantled U.S. climate policy. Emissions are still rising globally, with no sign that the world’s fastest-growing emitters, notably China, America, and India, are slowing down. As the executive director of the International Atomic Agency tweeted on Monday:

We expect energy-related CO2 emissions will increase once again in 2018 after growing in 2017 pic.twitter.com/rb0Em2folC

— Fatih Birol (@IEABirol) October 8, 2018Also on Monday, the world’s most influential climate research body released a report stating we only have 12 years to stop global warming of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—the point at which irreversible sea level rise, widespread food shortages, and massive coral reef die-offs will start to occur.

Written by 91 researchers on behalf of the U.N Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Monday’s report makes the case that allowing 1.5 degrees of warming is at least far better than allowing an increase of 2 degrees, which is the current goal of the Paris agreement. Only 70 to 90 percent of the world’s coral reefs would be wiped out under a 1.5 degree scenario, for example, but at 2 degrees almost all coral species would be gone. At 1.5 degrees, fisheries would only lose 1.5 million tons of fish per year, compared to more than 3 million tons at 2 degrees. Far fewer people would be exposed to malaria, dengue fever, and other diseases under a 1.5 degree scenario, and some low-lying island nations might not be wiped out.

Achieving this goal, however, requires rapid and massive global changes. Greenhouse gas pollution must be reduced 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030—and then by 100 percent by 2050.

This goal is technically achievable, according to both the report and Paul Romer, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics on Monday for his work on climate policy solutions. “It is entirely possible for humans to produce less carbon,” he said receiving the award, which he shared with William Nordhaus. “Once we start to try to reduce carbon emissions, we’ll be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as we anticipated.” Technological advancements in efficiency, combined with massive cultural shifts toward sustainability, could rapidly reduce human demand for energy. The world’s biggest governments could place heavy taxes on carbon dioxide emissions to reduce the incentive to consume. They could also heavily invest in reforestation, biofuels, and carbon capture, an unproven technology for taking carbon out of the atmosphere.

But very few people, scientists least of all, see these things happening by 2030. “Given the present political debate, I don’t see much chance of these near-term cuts happening, even in places that take climate very seriously,” said Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at at Texas A&M University. Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann agreed. “As I’ve stated before, 1.5 degrees Celsius is probably not realistically on the table,” he said. “We’re better focusing on achievable targets.”

Some might caution against these statements. Because when scientists and pundits say that 1.5 degrees Celsius is off the table, they tell the public that humanity will fail to save the coral reefs, the fisheries, and millions of people in developing countries, no matter what they do. They take away hope—and without hope, the public will resign themselves to doing nothing.

But it’s folly to rely on hope that is demonstrably false. “The whole idea that everything’s going to work out isn’t really helpful, because it isn’t going to work out,” said Kate Marvel, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Climate change is going to worsen to a point where millions of lives, homes, and species are put at risk, she said. The only thing humans can do is decide how many lives, homes, and species they’re willing to lose due to climate change—how long they’re willing to allow their respective governments to stall on what we know to be technically achievable.

Action relies on courage, not hope. “You shouldn’t need the guarantee of a happy ending to do what you know to be right,” Marvel said. Monday’s U.N. report gives us no logical reason to be optimistic about the planet’s survival, and no logical reason to hope. But pessimism just might convince enough people about the urgency of climate change, and encourage them to find the resolve to join the fight.

In April 2018, the Trump administration announced Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was open for business. By June, two Alaska Native Regional Corporations and a small oil company had already jointly applied to conduct extensive seismic testing in the refuge next winter.

Seismic blasts—loud sonic explosions fired through the ocean—map the seabed floor for oil and gas deposits to extract. Opponents, like the Wilderness Society and the group Polar Bears International, say the testing has deleterious effects on the land and the wildlife. The Canadian government has opposed opening up ANWR for these reasons as well.

Some Alaska natives support the oil exploration for its economic potential, while others, like the Gwich’in nation, argue that it would disrupt the caribou herd upon which their traditional diets—and much of their culture—depend.

Thousands of miles across the icy North, on the east coast of Canada, Inuit hunters several years ago worried about the same outcome in their own oil battle. They fought back—and won. As ANWR exploration draws nearer, the Canadian Inuit victory hints at an alternate path: lessons from a rare win for tribal communities fighting outside interests.

When the call on the radio came, the hunters of Clyde River swung into action. In pickup trucks and four-wheelers, they roared toward the tiny marina where dozens of boats bobbed in the current. They grabbed their guns and ammo, swung over the wooden sides of the boats, revved engines, and raced toward the inlet where the narwhal were spotted minutes before. It was the fall of 2016, and the Arctic whaling season was at full throttle.

Bruce Hainnu sped through the icy water with the other hunters and then cut his engine, leaning against the steering wheel as he scanned the horizon. His adopted son, Jacques Hainnu-Simard, explained they were looking for the plumes of mist that rise from whales’ blowholes.

The radio crackled to life again: The narwhal were staying close to shore, possibly to evade a killer whale. But then they dipped out of sight.

“It’s too choppy,” Bruce said. “Hard to see.”

Hunters looking for narwhals, polar bears and seals.

Hunters looking for narwhals, polar bears and seals. The hunters hunched against wind that took the temperature below zero, and continued scanning the waves of the frigid Arctic Ocean. After about 30 minutes or so with no further sightings, the two declared the trip a bust.

“We’re just wasting gas,” Bruce said, revving the idling engine and turning back toward shore.

“Time to turn in, and hope for better luck tomorrow,” Jacques said.

Hunting in the Arctic has never been easy. It takes years of experience navigating treacherous conditions, not to mention the expense of fuel and supplies in this far-flung corner of the Canadian Arctic.

But between 2015 and 2017, hunters like Bruce and Jacques found themselves facing their biggest challenge yet: a proposed oil exploration project that would make their livelihood all but impossible.

In 2014, Canada’s national energy board approved a five-year oil exploration project in Arctic waters. The permit would allow exploration along the entire coast of Nunavut’s Baffin Island—about 1,000 miles of the ocean between Canada and Greenland.

Jerry Natanine was mayor of Clyde River, which boasts a population of about 1,000 people, when the exploration project was approved. At first, he was elated. Oil exploration could bring much-needed jobs and infrastructure to the remote town, he thought.

But then he spoke with his father and uncle, who told him that seismic testing was not new in Clyde. Back in the 1970s, blasts to map the Arctic seabed had a profound impact on marine animals. When the hunters went out on the ice, lounging seals didn’t even notice their presence. As the hunters got closer, they saw pus dripping from the animals’ ears—they’d gone deaf. Without a sense of hearing, the animals couldn’t protect themselves from predators and risked dying in droves.

Jerry Natanine in his home in Clyde River.

Jerry Natanine in his home in Clyde River.“You have to fight it,” Natanine’s father urged him. “Do anything you can to stop it.” Potential damage would not be limited to the animals in the direct path of seismic blasts. Other animals, including polar bears, feed on marine mammals, while hunters and their families depend on Arctic animals for food, skins, and other supplies. The blasting could also affect migration patterns for seals, whales, fish and waterfowl.

Blasting could, Natanine argued, destroy “the whole ecology of the area.”

The energy board approved testing for five years, to take place when the river is free of ice—from about July to November. “Every day, 24 hours a day, just blasting every 15 seconds,” Natanine said.

To make matters worse, Natanine said, the project would bring few jobs, if any, to the community. Only a few engineers are needed to operate the sonar blasts, and they require special training—which no one in Clyde River possesses.

“There’s nothing here for Inuit. There’s no benefit,” Natanine said. “All they want to do is take the oil and leave and forget about us.”

Natanine appealed first to the National Energy Board, which had granted the permit; that appeal was denied. The next step was an appeal to Canada’s Supreme Court, but Clyde River had neither the funds nor the expertise to wage a long legal battle. Natanine was at a loss on how to proceed. He approached several indigenous and environmental groups, but no luck.

“No one would work with us. No one,” he said. “We were left out in the dust.”

In recent decades, the Inuit have faced many external obstacles to practicing their millennia-old traditions. In the 1950s and 1960s, the government forced the Inuit into permanent villages. Around the same time, officials killed most of the dog teams upon which the formerly nomadic hunters relied to move on the land—something Canadian authorities maintain was a matter of public safety, but the Inuit say it was done to make the relocations stick.

The hunters who were able to switch to motorboats and snowmobiles were dealt another major blow just a few years later. In the 1970s and 1980s, the environmental advocacy group Greenpeace lobbied for the end of seal hunting, introducing images of fluffy seal pups and bloodied Inuit hunters into the popular imagination. The resulting sealskin ban devastated Inuit communities; seemingly overnight, hunters could not sell sealskins and could not afford the expense of hunting by motorized vehicles for seal meat. Hunger, poverty, and addiction soon swept Nunavut’s communities.

“They made our lives living hell,” Natanine said of Greenpeace’s sealskin lobbying. “All the hardships of poverty, of not having money—that’s where it all started.”

Before oil companies began moving into the Arctic, Greenpeace was enemy number-one for many Canadian Inuit. But Natanine was desperate—and he was not blind to the changing times. Oil exploration posed a much bigger threat.

“Our lives are at stake now,” he said.

One day as he sat in the mayor’s office, he read Greenpeace’s apology in a newspaper for the organization’s devastating role in the sealskin ban. Natanine saw a way to mend the divisions of the past—and to save Clyde’s future. He approached the organization and asked them to provide legal help. Greenpeace agreed, and the two joined forces to take the seismic testing case to Canada’s highest court.

Clyde’s residents weren’t just worried about the tests—they were also concerned about the effects of oil drilling, if resources were discovered.

The only grocery store in Clyde River.

The only grocery store in Clyde River. “If there was an oil spill, it would affect us right away. And if it happened during winter, there would be no way to clean up the oil spill,” Natanine said. “It would devastate our lives.”

Nick Illauq, a product of a traditional hunting family and a member of community group Fight Against Seismic Testing, said the “resources” to clean up a spill don’t exist in this area. And the oil industry, he argued, is dying. Even if oil were discovered, the companies conducting seismic tests might conclude that the conditions in the Arctic make drilling prohibitively difficult and expensive. By then, Illauq worried, it would be too late—marine mammals would be gone along with the livelihoods of Clyde residents.

“This issue is one of the most important things we’ve ever fought against,” he said.

Instead, Illauq hoped his hometown could capitalize on its other more renewable natural resources.

“We have a never-ending wind supply,” he said. “We have 24 hours of sunlight for 79 days straight.”

With the help of its new partner, Greenpeace, Clyde River installed solar panels on their community center last summer, to meet some of the village’s energy needs. The panels are owned by the community, and several locals were trained on how to install and maintain the arrays.

In the meantime, the Inuit of Clyde River waited for the Supreme Court to decide the fate of their community.

The battle was called Justin Trudeau’s first major environmental challenge, but it resonated outside of Nunavut and around the world. The decision would set a precedent for existing and future indigenous land disputes, and it would also likely have implications for other seismic testing battles around the world, such as in New Zealand and Peru.

The Court heard Clyde’s case on November 30, 2016. A few weeks later, Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a promising announcement: all Arctic waters would be “indefinitely off limits to future offshore Arctic oil and gas licensing,” subject to review every five years.

But Trudeau’s new rule only applied to future oil and gas permits. The residents of Clyde River continued to wait for the court decision, which they feared they would lose. “I am thinking it will be against us,” Nick Illauq said in early July 2017, interpreting the federal government’s move to educate communities on natural resource regulatory systems as a bad sign.

Then, after eight months, the decision came through. In a unanimous decision handed down on July 26, the court ruled that the National Energy Board consultations with the residents of Clyde River were “significantly flawed” and did not take into account the massive impact the oil exploration would have upon Inuit lives.

The Inuit had won. Seismic testing would not proceed.

“What a victory for us,” Jerry Natanine said in a press conference. “Justice was on our side because we’re fighting for our life, fighting for our way of life.”

Clyde River held a celebration to honor the decision. Natanine was emotional and overjoyed—and he was also relieved. “There was this big sigh of relief in our community to realize the fact that we were on the side of justice all along,” he said.

Asked recently about other communities looking to resist oil exploration around ANWR and elsewhere, Natanine highlighted the importance of community.

“The biggest thing for us was that we were united,” he said. Decisions were made in joint meetings between hamlet officials and the Hunters and Trappers Office. These decisions were then announced on the local radio station—the main form of mass communication in Clyde, other than Facebook—requesting feedback from the public. And, of course, partnering with outside organizations helped boost their message. “All the people that we networked with, that gave us advice, and that knew how the system of appealing works,” he said, “were very beneficial in all that we were doing.”

Natanine wasn’t just relieved that the fight against seismic testing was successful. He was also pleased that the partnership with Greenpeace, seen as a huge risk in the community at the time, became an unexpected blessing.

“It was one of the best parts of the case as we, as a community, were able to deal with the historic trauma that we experienced through the seal ban,” he said.

By banding together against a new threat to their livelihoods and well-being, he said, Greenpeace and the Inuit community—previously opponents—finally found closure for decades-old upheaval, and discovered a way to make their voices heard on future issues.

To win these battles, communities need to articulate the effects of oil exploration on lives and livelihoods. To wage the battle, they need alliances.

Melody Schreiber and Camilla Andersen reported from Nunavut on a fellowship with The GroundTruth Project.

No comments :

Post a Comment