Linguists have figured out a lot about the many different regional dialects of American English. They know why Brooklynites say “cawfee,” for example, and why Bostonians say “Hahvahd Yahd.” They’ve traced the history of our accents and phrases: how migration patterns influenced their development, and how technology shaped their recent evolution. But what do they know about how Americans will talk in the future?

Not a lot. Outliers in the field believe that the dialects of American English will die—or at least slowly fade—as technology expands connections between people from different regions. But everyone agrees that Americans won’t always speak like we do today. And one of the best ways to predict those future changes is to study places where American speech is shifting right now.

One of the most interesting such transformations is happening in New Orleans, according to Katie Carmichael. The linguistics researcher and assistant professor at Virginia Tech has been researching the Southern Louisiana city’s unique drawl for years. “It changes every six months, who lives there and what they’re arguing about,” she said. “Every time I go back there, it’s such a different place.”

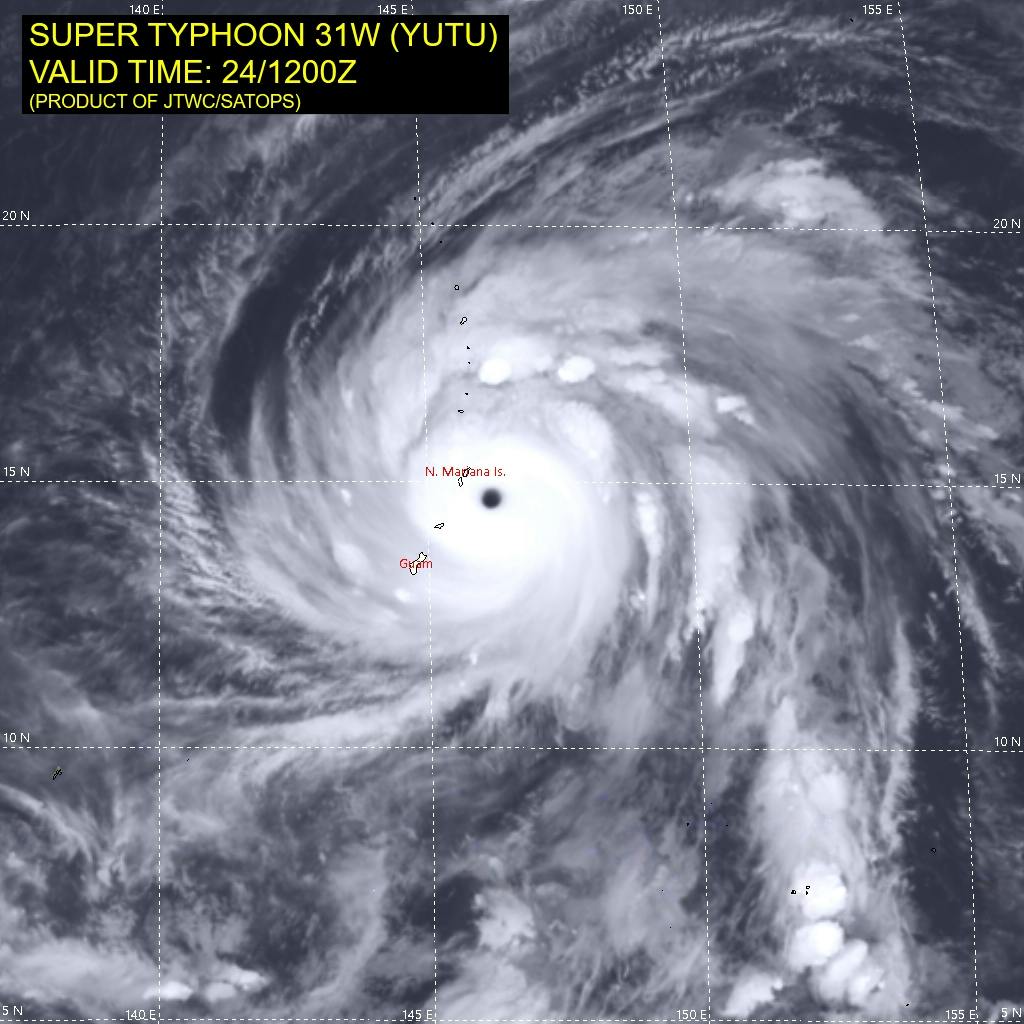

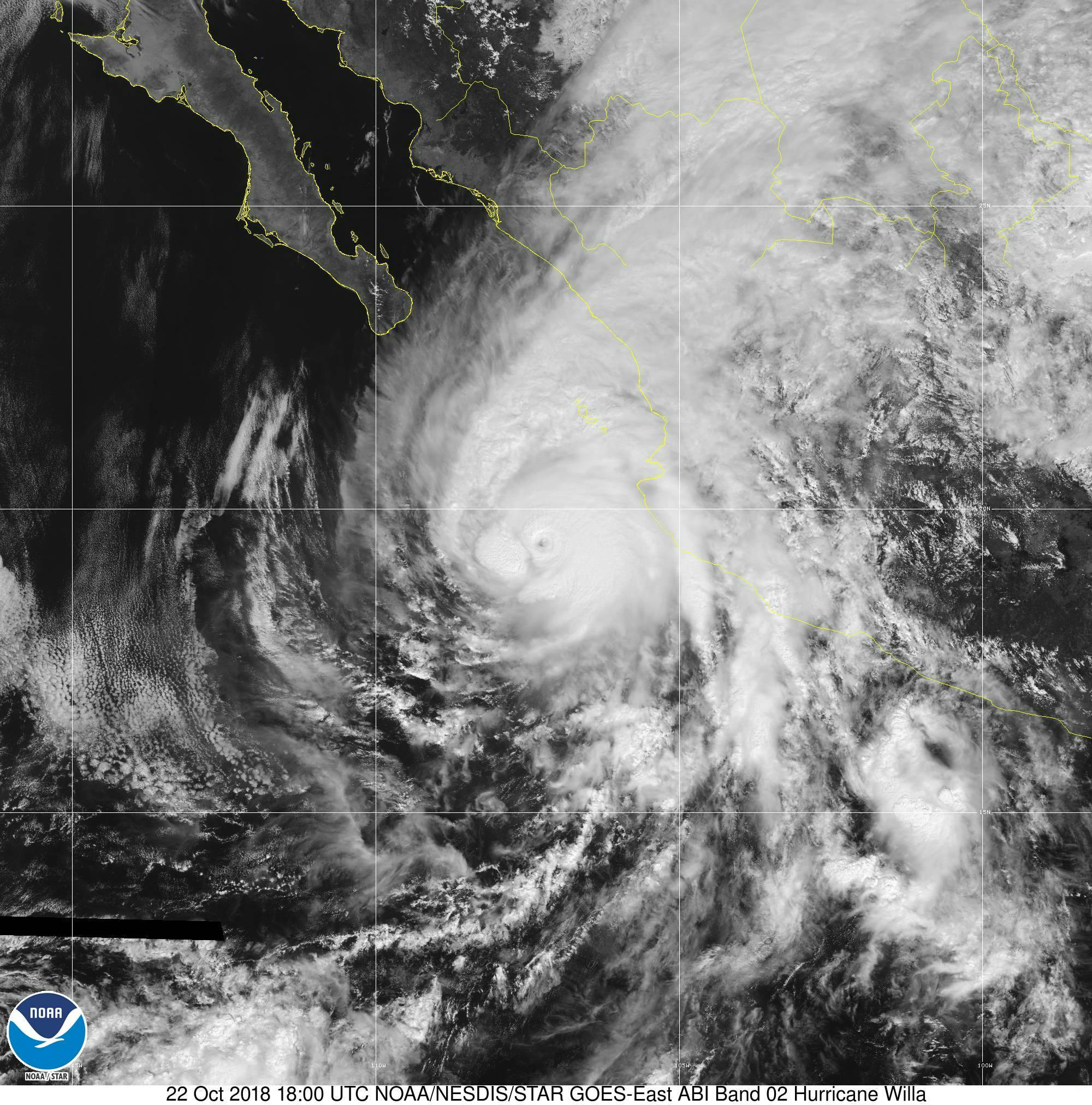

In years of conversations with New Orleans residents, however, Carmichael has noticed one thing that’s always the same. “There’s not a single person who doesn’t bring up Hurricane Katrina,” she said. That observation led Carmichael to develop a unique hypothesis: Maybe the hurricane that devastated New Orleans in 2005 did more than just change the city’s physical and cultural landscape. Perhaps it altered how New Orleanians speak, too.

New Orleans English can be confusing to those who aren’t familiar with it. “Some of them speak with a familiar, Southern drawl; others sound almost like they’re from Brooklyn,” Jesse Sheidlower, the former editor-at-large of the Oxford English Dictionary, wrote in a definitive explainer of the dialect in 2005, shortly after Katrina. “Why do people in New Orleans talk that way?”

The “rich level of linguistic diversity” in New Orleans stems, in part, from its diverse migrants, he wrote. There were the French and Acadian settlers, of course, as well as Spanish, German, Irish and Italian immigrants. New Orleans was also “a gateway for the slave states, which brought in speakers of a variety of African languages.” The result was the hodgepodge of subdialects that exist there today, which change depending on the neighborhood or ethnic group.

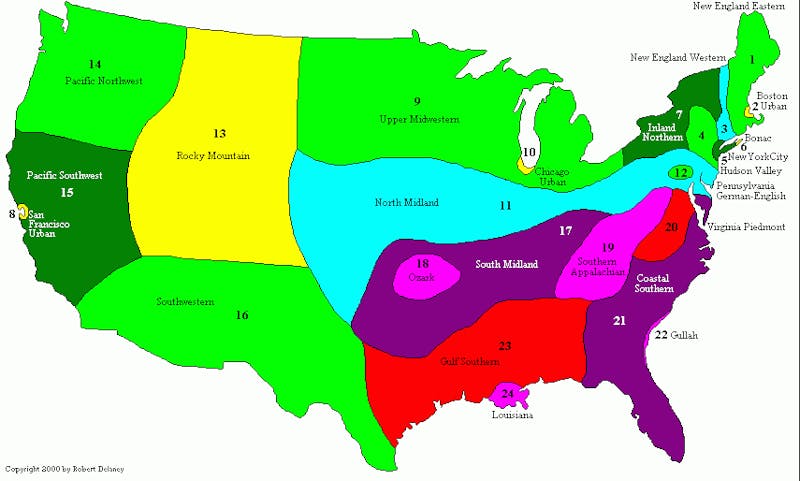

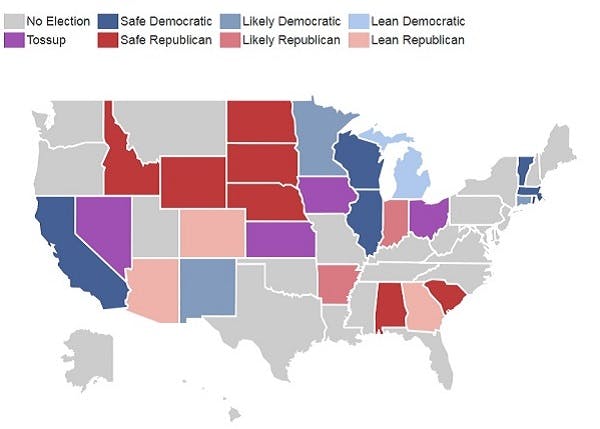

The 24 regions of American English, according to Long Island University’s Robert Delaney.Robert Delaney

The 24 regions of American English, according to Long Island University’s Robert Delaney.Robert DelaneyCarmichael can’t yet say specifically how New Orleans English has changed since Katrina. But last week, the National Science Foundation awarded a $250,000 grant to Carmichael to explore her hypothesis, along with Tulane University linguistics professor Nathalie Dajko. Together, they “will interview 200 lifelong residents of different ethnic backgrounds and neighborhood origins to collect the largest and most diverse data sample ever assembled in the city,” according to a press release. The results could help researchers predict other dialect changes that might occur as sea-level rise and more severe storms force Americans away from the places that once shaped their speech.

Carmichael’s hypothesis is based on two known impacts of Katrina that are also known to spur dialect changes: Widespread displacement of native speakers from the region and widespread migration of non-native speakers into it.

Katrina’s flooding displaced 400,000 people—nearly the entire population of the city. A year later, only about 53 percent of those people had returned—“less than a third at the home they’d lived in prior to Katrina,” according to CityLab. Today, the city has around 80 percent of the population it once had, but it’s been difficult to track with precision how many are newcomers and how many are longtime residents. But one thing is for sure: New Orleans is a smaller, whiter city than it used to be. There is thus concern that some New Orleans subdialects could be at risk of disappearing. After all, Carmichael said, “Some of our major cities in the South no longer sound Southern because economic prosperity brought Northerners in.”

A severe example of climate change–fueled displacement is happening not far from New Orleans at Isle De Jean Charles, a Louisiana island that’s slowly sinking into the ocean. The community there is one of the last vestiges of Louisiana Regional French, and some scholars worry that an exodus of residents—who are often called America’s first climate refugees—will eradicate that dialect. “Sometimes when people move away, they leave the language behind,” said Dajko, who is writing a book about linguistic changes on the island.

There is hope, though, for both New Orleans English and Louisiana Regional French, and it rests in part on the strong sense of identity that comes with a unique way of talking. If people feel their identity is threatened—that their dialect is fading—they may work harder to preserve it. Carmichael hypothesizes that as a result of Katrina, some ethnic populations in New Orleans may retain their unique older dialects for longer than they would have otherwise.

While she and Dajko work to figure that out, though, they hope the mere idea of their research will provoke others to think about how climate change might affect American English in the future. “These mass migration scenarios are more likely to happen again,” Carmichael said. That’s not only because of hurricanes, which are getting more intense, but also due to sea-level rise.

If warming continues unabated, up to 13.1 million Americans living in coastal areas could be permanently displaced. More than one million people are at risk in Louisiana, further threatening the regional dialect. But so are 900,000 in New York, 800,000 in New Jersey, and 400,000 in Texas. “Climate change is going to be a catalyst for a mass migration that will result in language change,” Dajko said. What that heralds for y’all and yous guys remains to be seen.

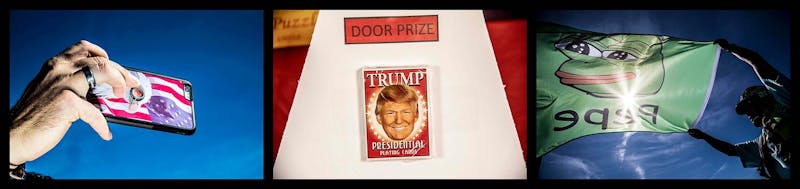

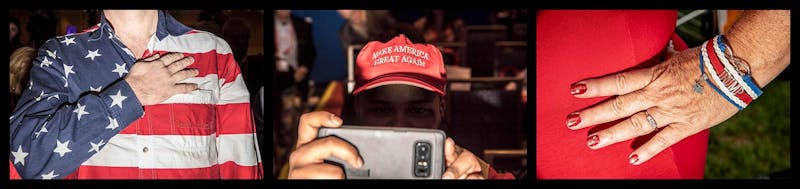

How divided have Americans become? When it comes to the two-party war, the differences could not be starker. Pew Research Center has reported that 55 percent of Democrats are “afraid” of the Republican Party and nearly half of Republicans are similarly fearful of Democrats. These survey results were published in June 2016—before Donald Trump was elected. Since then, of course, the enmity has increased. Trump’s genius for stirring up discord is one reason, but only one: The ingredients of all-out political warfare have been simmering for many years, as each of the two parties has discarded the old-fashioned ideal of the “big tent” and enacted its own purifying rituals.

What has changed is how personal these political divisions have become. Partisanship has taken on an unsettling aspect and turned into something new: “affective polarization,” which dictates not only how we vote, but also, as social scientists have reported in the Harvard Business Review, how we “work and shop.” Politically minded consumers are “almost twice as likely to engage in a transaction when their partisanship matched the seller’s,” and they are “willing to work for less money for fellow partisans.” Is this honorable self-sacrifice or self-inflicted injury? It is hard to say, especially since, when it comes to political dispute, “particular policy beliefs” are often beside the point, the researchers write. What matters is who wants the new bill passed and who wants it stopped. It’s a zero-sum game in which victories are less important than the other side’s defeats.

THE POLARIZERS by Sam RosenfeldUniversity of Chicago Press, 336 pp., $30

THE POLARIZERS by Sam RosenfeldUniversity of Chicago Press, 336 pp., $30Yet, as Sam Rosenfeld shows in The Polarizers, the irrational-seeming “extreme partisanship” and “tribalism” that contaminate our politics today originated in the principled efforts of writers, activists, and politicians who thought the two parties needed more polarization, ideological fixity, and internal discipline. This idea went back to the New Deal era, when the two major parties were each riven by internal disagreements on race, the economy, and much else, so that President Roosevelt met opposition in Congress not only from Republicans but also from Southern Democrats. He tried to fix the problem, first mounting a campaign to purge conservatives from the Democratic Party in the 1938 midterms (it backfired) and then inviting the moderate Republican nominee he defeated in 1940, Wendell Willkie, to join him in a plan to break apart the two parties and reset them like straightened limbs, “one liberal, and the other conservative.”

Today that course seems fatefully misguided, but Rosenfeld is right to point out that what came before wasn’t always better. What some enshrine as an age of “statesmanlike civility and bipartisan compromise” often involved dark bargains and “dirty hands” collusions, and was not especially democratic. This is what led political scientists such as E. E. Schattschneider and James MacGregor Burns to argue in the 1940s and 1950s against bipartisanship, because it depended on toxic alliances that hemmed in political players, from presidents on down. Thus, even the immensely popular war-hero Dwight Eisenhower, the first Republican president elected in 24 years, was stymied time and again by in-built flaws in a defective system. Eisenhower wanted to do the sensible thing—to advance civil rights and economic justice at home while negotiating abroad with the Soviet Union. He repeatedly came up against a stubborn alliance of conservative Southern Democrats and heartland Republicans.

Out of all this came the drive to reform the two parties, to make them more distinct through what Rosenfeld calls “ideological sorting.” The hope was that clear agendas, keyed to voting majorities, would marginalize the reactionaries and extremists in both parties, and that mainstream, “responsible” forces would govern from the center, giving the public the expanded, activist government it obviously wanted. This was the initial promise of polarization. What went wrong?

For one thing, Schattschneider and Burns were viewing the system from the heights of presidential politics, where centrism did indeed dominate. The ideological distance from FDR in 1932 to Eisenhower’s successor Richard Nixon, elected in 1968, was not great. World War II and cold war “wise men” could be either Republicans or Democrats. They belonged to the same establishment, attended the same Ivy League colleges, were members of the same clubs, read the editorial pages of the same few newspapers. Two parties organized around such leaders could each have presented a coherent agenda, one to the left of center, one to the right, meeting in the middle.

It was the consensus ideal, and it ignored deeper tensions in parts of the country where politics was harder-edged and culturally driven. An ideology nourished in the small-town Midwest and rural South and in the growing population centers of Western states resented and opposed the approach, style, and transactional presumptions of East Coast elites. And this resistance found support from right-wing intellectuals, heirs to pre-World War II “Old Guard” conservatism. Its best minds coalesced around National Review, founded as an anti-Eisenhower weekly in late 1955. Rosenfeld has much to say about the magazine, but he leaves out its most original and penetrating thinker, the Yale political scientist and NR columnist, Willmoore Kendall. An incisive critic of the Schattschneider-Burns thesis, he helped coin the term “liberal Establishment” and theorized that proponents of the “presidential majority” seemed to be wishing away the second, “congressional majority” elected every two years and therefore more directly accountable to voters.

Burns could argue that the “true” Republican Party naturally reflected Eisenhower’s internationalism, because influential people—including the publishers of The New York Herald Tribune and Time magazine—approved of him. But much of the GOP base gave its loyalty to local figures, whose views more closely resembled their own on the whole range of issues: civil rights and civil liberties, military spending and foreign aid, free trade and the national debt, even “the scientific outlook.” When it came to these matters, the people’s tribune wasn’t Eisenhower, the five-star general, who had been the “supreme commander” of NATO and the president of Columbia University. It was Senator Joseph McCarthy, who became the hero to the emerging postwar right. His most eloquent defender, National Review’s editor, William F. Buckley Jr., applauded McCarthy’s Red-hunting investigations and ridiculed the tu quoque hypocrisies of McCarthy’s “enemies”—liberals and moderates in both parties.

Rosenfeld is curiously silent about all this. He praises Buckley’s 1959 manifesto Up From Liberalism, calling it a “thorough formulation of the connection between building a conservative ideological movement and recasting the party system.” In fact, Buckley said little about this, apart from restating the case for McCarthy. It was puzzling to readers, including some on the right, that Buckley never got around to saying what conservatism meant or even what conservatives should do. When he talked about policy, it was mainly to denounce liberal proposals—on voting rights, health care, battles between labor and management—without offering any serious alternative in their place. What would a truly conservative administration do if elected? Buckley had no idea, “Call it a No-program, if you will,” he cheerfully wrote or shrugged, in words that sound like marching orders for today’s GOP. Undoing or rolling back the New Deal and post-New Deal programs already in place would suffice. “It is certainly program enough to keep conservatives busy.”

Buckley wasn’t being flippant. He was being honest. Conservatives really did have no interest in social policy. National Review writers excelled at philosophical theory and high rhetoric, but when the subject turned to “a crucial policy issue such as Medicare, you publish a few skimpy and haughty paragraphs,” Buckley’s friend Irving Kristol complained in 1964, when it was clear some kind of national health care for the elderly was going to be enacted, expanding the popular protections in Social Security. “Why not five or six pages, in which several authorities spell out the possible provisions of such a bill?” Kristol urged. “It could really affect the way we live now.” Buckley wasn’t interested, and Kristol plugged the hole himself with The Public Interest, the quarterly he founded with Daniel Bell in 1965. It was one of the era’s best journals, filled with well-written analysis and incisive commentary on the entire range of midcentury policy. But in the end, Buckley was right. As Rosenfeld says, it was National Review that gave direction to the conservative revolution and made the GOP better organized and more ideologically unified than the “polarizers” of the ’40s and ’50s could imagine.

Buckley’s brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell, was a key figure in translating these ideas into political strategy. He brilliantly repackaged Buckley’s “No-program” in a tract he ghostwrote for Barry Goldwater, The Conscience of a Conservative, meant to launch a shot-across-the-bow challenge to Nixon in 1960. In a famous passage, Bozell and Goldwater project a vision of the ideal “man in office,” the savior of the Republic, who tells the people,

I have little to no interest in streamlining government or in making it more efficient, for I mean to reduce its size. I do not undertake to promote welfare for I propose to extend freedom. My aim is not to pass laws, but to repeal them.

When the book became a best-seller and the guessing game of authorship began, Goldwater insisted he had written it—or that it grew out of his speeches and published writings (never mind that they’d been ghosted too). Under normal conditions, few would have cared—John F. Kennedy didn’t write his books either. But Goldwater was being marketed as a bold political thinker. Rosenfeld perpetuates this myth, the better to present Goldwater as a serious-minded intellectual who “framed his positions on disparate issues within an overarching ideological vision.” That vision consisted of libertarian economics at home and militant anti-Communism abroad. Goldwater didn’t come close to getting the nomination. Nixon did, as expected, and then lost, barely, to John F. Kennedy—another victory for the liberal Establishment.

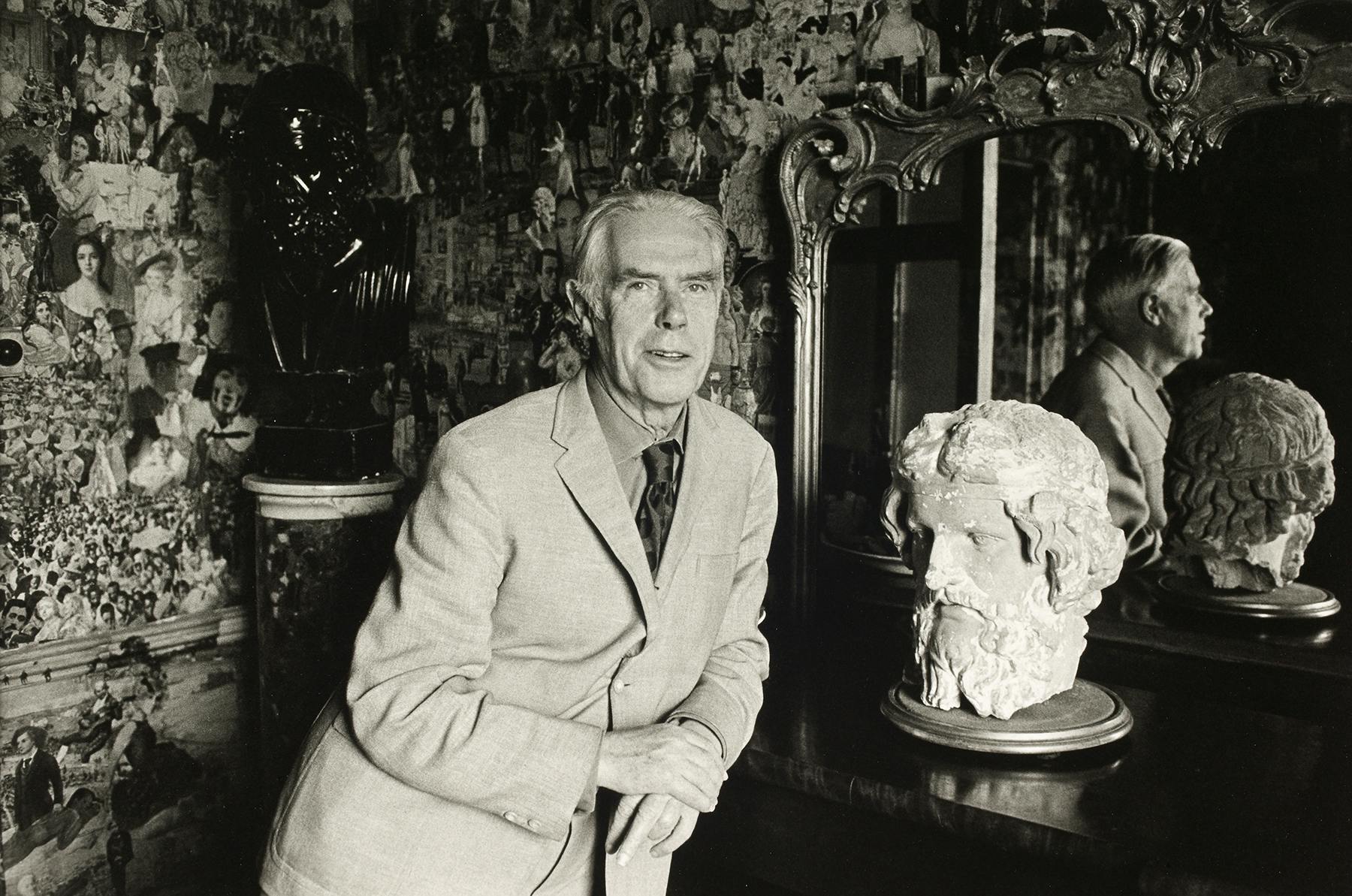

Ronald Reagan and Barry Goldwater join William F. Buckley and his brother at a National Review party. Bettmann/Getty

Ronald Reagan and Barry Goldwater join William F. Buckley and his brother at a National Review party. Bettmann/GettyGoldwater was too good a politician to chain himself to a single script, especially a losing script. It was dawning on some that Kristol had got one big thing right. The public really did want government programs, as long as the benefits accrued to them and not someone else. In early 1961, getting a jump on the next election, a second Goldwater ghostwriter, Michael Bernstein, drafted a prescient document, the “Goldwater Manifesto” or “Forgotten American” speech. It sketched out the beginnings of what later came to be called big-government conservatism—a reordering of spending away from the poor and minorities (singled out for help by Kennedy’s New Frontier) and toward a newly aggrieved group, “the silent Americans,” who truly “constitute the substantial majority of our people” and yet “cannot find voice against the mammoth organizations which mercilessly pressure their own membership, the Congress, and society as a whole for objectives which these silent ones do not want.”

What might the silent ones want instead? For one thing, Bernstein proposed, “tax relief for families with children attending college.” NR purists were appalled. This was still Big Brother—manna flowing from the Beltway—even if, in this case, the money was going back to overburdened taxpayers. In embarrassment, Goldwater backed away and made a new calculation. The most numerous “silent” votes were to be had in the South. White majorities there felt disrespected or worse by the presidencies of Kennedy and his successor, Lyndon Johnson. Civil rights was the pivotal issue, but not the only one. In fact, it overlapped with other tensions: in labor unions, public education, housing, anti-colonial uprisings abroad. Below the calm surface of consensus, a deeper struggle was going on. “There is a vague and bitter counter-revolution in this country—anti-big government, anti-union, anti-high taxation, anti-Negro, anti-foreign aid, and anti-the whole complex spirit of modern American life,” James Reston, The New York Times’ Washington bureau chief and most respected columnist, wrote in 1963, when Goldwater was the uncrowned king of an increasingly conservative GOP. The center that Schattschneider and Burns had counted on was coming apart.

What Reston missed was the sophistication of Goldwater’s rhetoric, helped along by the writings of Buckley, Bozell, and Bernstein. He overlooked as well the Southern strategy devised by NR’s publisher, William Rusher. It wasn’t a new idea. Goldwater’s first stab at the presidency, in 1960, had begun in South Carolina, when he won the delegates at the state Republican convention, catching Nixon off-guard. It was his first successful “duck hunting” expedition—that is, courting the votes of middle-class whites in the “New South,” with its rising business class. Uncomfortable with the overt race-baiting of Dixiecrats, these voters responded to a broader argument cast in the language of states’ rights and free enterprise, the true pillars of the constitutional republic as opposed to the Democrats’ promise of egalitarian democracy. You could make this case, and Goldwater did, without mentioning race at all. Buckley made the same adjustment. Instead of saying black people were inferior—National Review’s line in the 1950s—he now argued that Goldwater “does not intend to diminish the rights of any minority groups—but neither does he desire to diminish the rights of majority groups.”

While Democrats had become the party of civil rights, the Republican Party, without explicitly saying so, “was now a White Man’s Party,” as Robert Novak put it in his account of the 1964 election, The Agony of the G.O.P. The transformation began in earnest when Senator Strom Thurmond quit the Democratic Party, taking South Carolina’s electoral votes with him, and was welcomed into the GOP by his good friend Goldwater. Thurmond the defecting Democrat was joined by younger Southern politicians nourished within the GOP. These were figures like James Martin, who challenged and nearly unseated Lister Hill, the four-term incumbent Democratic senator in Alabama, in 1962. Martin was elected to the House in 1964, together with five others from the South, four of them from states—Tennessee, Texas, Florida, and Kentucky—that today contribute to the GOP’s base. Canny operatives like the Alabama prodigy John Grenier (oddly absent from Rosenfeld’s book) rose to top positions in Goldwater’s campaign. Its victories came almost entirely from the Deep South.

While Democrats had become the party of civil rights, the Republican Party, without explicitly saying so, “was now a White Man’s Party.”

Outside the South (and his home state, Arizona), Goldwater got a thrashing in 1964. But he had opened up the route to what the political strategist Kevin Phillips soon called the “emerging Republican majority,” which nationalized the Southern strategy by courting alienated white voters in the North as the civil rights movement moved there; by focusing on racially charged issues like “forced busing” and the integration of labor unions, the GOP drove a wedge in what had once been Democratic strongholds. In 1968, Richard Nixon dusted off Bernstein’s “forgotten man” speech and made it the template for his appeal to the “silent majority,” as Garry Wills reported in his classic Nixon Agonistes. Like Goldwater, Nixon cast tribal politics in lofty ideological terms. He talked of “positive polarization” and promised to overturn “the false unity of consensus, of the glossing over of fundamental differences, of the enforced sameness of government regimentation.” Ronald Reagan, preparing to run in 1976, went even further, warning that if Republicans continued “to fuzz up and blur” the differences between the two parties when they should be “raising a banner of no pale pastels, but bold colors,” he might quit the GOP and form a third party. Instead he contested and badly weakened the incumbent Gerald Ford. Four years later, Reagan repeated the Goldwater and Nixon formula, rechristening the “forgotten American” and “silent majority” as the “moral majority,” and won in a landslide.

For all this talk of the fundamental differences between the parties, however, partisanship did not yet reach today’s poisonous extreme. Nixon and Reagan, experienced leaders, ran “against” government while also realizing there were very few programs the voting public would be willing do without. Once in office, Republicans too were expected to make the system work. Democrats, with their long history of taking public policy seriously, were, however, better at it—as some conservatives acknowledged. In his influential book Suicide of the West, Buckley’s colleague James Burnham quoted Michael Oakeshott, who said fixing social problems was the liberal’s ambition, or delusion. While the liberal “can imagine a problem which would remain impervious to the onslaught of his own reason,” Oakeshott wrote, “what he cannot imagine is politics which do not consist in solving problems.” The conservatives’ job was to apply the brakes when necessary, to keep alive the opposition argument in a world in which all knew liberalism remained the basis of modern governance but weren’t always prepared to admit it.

This broad but tacit acceptance of activist government is what inspired the Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan to take a job in Nixon’s administration in 1969. He gambled that a moderate Republican, who said he disliked government but realized voters wanted it, might succeed in passing legislation where Democrats had failed. Despite encountering resistance from the “congressional majority,” Moynihan was vindicated. The Nixon years gave us a good deal of effective government. They saw the creation of the EPA, wage-and-price controls, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, Supplemental Social Security income (for the blind, disabled, and elderly), Pell Grants (college loans for lower-income students), the Endangered Species Act, and more. It was a “rich legislative record,” as the political scientist David Mayhew has written. The reason is conveyed in the title of Mayhew’s book, Divided We Govern, which showed how well government worked when voters split tickets and gave each party control of a different branch.

Rosenfeld’s thesis—that the postwar enthusiasm for ideologically unified parties yielded some positive good—works better when he turns to the Democratic Party, which really did clean house, cutting loose Southern reactionaries to make itself the party of civil rights. Stalwarts of the Senate “citadel” like Harry F. Byrd and Richard Russell lingered, but with diminished authority as civil rights became the party’s great cause, and Northern liberals—the Minnesotans Hubert Humphrey and Eugene McCarthy, to name two, and the Prairie populist George McGovern—gained national followings. There were also the brave organizing efforts of college students, white and black, who mobilized citizens in the South. Rosenfeld has very good pages on the 1964 Democratic convention, when members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, led by the activists Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer, challenged the Dixiecrats. Their victory was symbolic, but politics is often written in symbols.

One wishes Rosenfeld had more to say about other political figures, particularly black leaders such as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, and Shirley Chisholm, who guided the Democrats’ response to the most important polarization in America. Kendall’s “two majorities”—one “presidential,” the other “congressional”—only grazed the surface of a nation profoundly split into “two societies, one black, one white— separate and unequal,” to quote one of the period’s great public documents, The Kerner Report. Published in 1968 after a year of investigation by a presidential advisory commission, the report explored the causes of the urban disorder in almost 150 cities—especially Detroit and Newark—in the summer of 1967.

In April 1968, while the Kerner commission findings were still being digested, King was assassinated, and the two societies hardened along lines that prefigure today’s jagged divisions. Trump’s truest forerunner, many have pointed out, was the one true radical in the 1968 presidential campaign, the Alabama segregationist George Wallace, a lifelong Democrat who ran on a third-party ticket and preached a Trump-like gospel of revenge. “The desire for ‘law and order’ is nothing so simple as a code for racism,” Garry Wills wrote of Wallace’s message at the time. “It is a cry, as things begin to break up, for stability, for stopping history in mid-dissolution.” Fifty years ago, “middle America” already yearned to make their country “great” again.

In truth it was becoming great—or better, anyway. Rosenfeld’s book, though the last pages rush through the years between 2000 and 2016, says very little about President Barack Obama, whose two terms were a model of “responsible party” politics, ideologically moored but also pragmatic and aimed at the broad middle of the electorate. It led to much good policy, and to the strong economy that is now buoying Trump’s presidency. Why does Rosenfeld have nothing to say about Obama? One answer might be that Obama was detached from the Democratic base: It steadily eroded during his two terms, especially at the all-important state level, as Nicole Narea and Alex Shephard wrote soon after Trump was elected. The Republicans, meanwhile, had diligently rebuilt from the bottom up, bringing about today’s “relentless dynamics of party polarization” and a climate of “factional chaos.”

Rosenfeld blames our current partisan gridlock on the system’s “logic of line-drawing.” But he also warns that “any plausible alternatives to the rigidities and rancor of party polarization might well prove to be something more chaotic and dangerous.” What can he mean? He points to the dangers of “pragmatic bargaining” and to the unprincipled compromises that might take the place of “effective policymaking.” This, he worries, would leave us with the same problems Schattschneider and Burns identified decades ago. Yet the last half-century of legislative history suggests something very different: The only coherent policies we’ve seen in decades—from the great civil rights legislation of the 1960s through Medicare and then Reagan’s tax reform in the 1980s—owe their passage to exactly the bipartisanship Rosenfeld finds corrupting. The lone recent instance of one-party rule creating a powerful piece of legislation is the Affordable Care Act, and the bill was vulnerable to attack precisely because no Republicans in either the House or the Senate voted for it and so had no stake in protecting it.

In one important way, however, Rosenfeld could be right about the ultimate benefits of polarization. In the Desolation Row of the Trump era, “Which side are you on?” has become the paramount question. Trump’s coarseness has invigorated the forces of resistance: A politer figure would not have given us the Access Hollywood tape, and the brazen denials afterward, and would not have fed the outrage that burst into public consciousness with the “Me Too” movement. So too Trump and Paul Ryan’s failure to come up with a workable replacement for Obamacare—a failure rooted in half a century of a “No-program program”—has given Democrats one of their most potent issues in the midterms. And the excesses of House Republicans, especially the foot soldiers in the Freedom Caucus, may well create opportunities for another disciplined group whose presence has been growing on the other side, the Congressional Black Caucus. If these changes come, polarization will be a major reason. The most enduring accomplishment of Trump and Trumpism— the latest, most decadent stage of the American right—could be the rebirth of an authentic American left.

“Bring the war home.”

That’s what protesters at the University of Wisconsin chanted in early 1970, denouncing defense-related research at the school during the Vietnam War. Later that summer, four men brought the war to campus. They set off a bomb at the Army Mathematics Research Center, killing a physics graduate student and injuring three others.

Critics were quick to blame the entire antiwar movement. But the attack also triggered sober reflection among the protesters, who asked themselves whether their increasingly aggressive language had encouraged it.

That’s precisely the kind of honest, good-faith reckoning that’s been missing among most Republicans in recent days. Last Friday, police said that a Florida supporter of President Donald Trump, Cesar Sayoc, was responsible for sending explosive packages to Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and several other prominent Democrats. Then, on Saturday, 11 people at a Pittsburgh synagogue were murdered by alleged gunman Robert Bowers, who reportedly didn’t vote for Trump but had posted diatribes echoing the president’s overheated rhetoric about the caravan of migrants from Central America.

White House officials responded defensively after both attacks, denying that Trump’s language might have helped provoke them. “The president is certainly not responsible for sending suspicious packages to someone, no more than Bernie Sanders was responsible for a supporter of his shooting up a Republican baseball field practice last year,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said, referring to the attack that critically injured Republican Congressman Steve Scalise last year.

But Bernie Sanders hasn’t encouraged people to behave violently; Trump has. He urged supporters at a rally to “knock the crap” out of anti-Trump protesters, promising to pay any resulting legal bills. He has continuously praised Montana Congressman Greg Gianforte for body-slamming a news reporter. And he grinned happily last week while supporters chanted “CNN sucks,” just days after the network received one of Sayoc’s mail bombs and mere hours after news reports showed Sayoc’s van bearing a bumper sticker with the same slogan.

And Trump certainly fueled anti-Semitic theories that the Central American caravan is funded by Jewish philanthropist and top Democratic donor George Soros, which was a recurring theme on Bowers’s social media account. Trump didn’t name Soros, whom Sayoc also targeted with a bomb, but warned that the caravan “didn’t just happen” and that “a lot of money” was “passing” to it from outside. That’s a clear nod to conspiracists like Bowers.

On Friday, Trump acknowledged that Sayoc “preferred” him over other political candidates. But he refused to admit that his own behavior could have encouraged Sayoc’s assassination attempts. “There’s no blame,” Trump declared. “There’s no anything.”

His comment brought me back to the 1970 bombing at the University of Wisconsin, which shook the antiwar movement to its core. Instead of simply distancing themselves from the attack, protesters asked hard questions about how their own actions might have helped provoke it.

The same bombers had previously tossed a firebomb into an ROTC classroom at the university. And a few days before the 1970 New Year, they stole a plane and dropped a series of explosives onto a nearby ammunition plant. Nicknamed “The New Year’s Gang,” they were lionized as romantic heroes by Wisconsin’s student newspaper and other protesters at the university.

But after the destruction of the math building and the death of the physics student, a 33-year-old father of three, protesters changed their tune. The bombing “was so extreme and unjustifiable and horrible, it stopped us in our tracks,” one activist said. Another noted that the attack “caused a lot of soul searching.” It was “a very pointed reminder . . . that you can’t persuade people of the sanctity of human life by being recklessly unmindful of human life.”

When will Republicans search their own souls about the reckless rhetoric that provoked Sayoc and Bowers? Several GOP senators have released generic statements denouncing violence and calling for civility. But all of these comments ring hollow when they exempt the man who has done more than anybody else to encourage violence and erode civility. “Look, everyone has their own style. And frankly, people on both side of the aisle use strong language about our political differences,” Vice President Mike Pence told NBC News on Saturday. “But I just don’t think you can connect it to threats or acts of violence.”

It’s true that Congresswoman Maxine Waters and a few other Democrats in Congress have engaged in their own kinds of incivility, such as calling on supporters to confront Trump administration officials in restaurants. But the Democratic leadership has unequivocally condemned their behavior.

I’m not expecting Republicans to stop supporting Trump’s policies, just as the protesters in Wisconsin weren’t about to abandon their opposition to the Vietnam War over the actions of the New Year’s Gang. But not a single prominent Republican has stood up over the past few days to state the obvious: Trump’s violent rhetoric encourages violent action.

Decent people can endorse Trump’s views on immigration, health care, taxes, and so on, but decent people do not speak and act like he does. It’s time for Republican leaders to say that, clearly and unequivocally. If they don’t, they will be complicit in any further right-wing political violence that mars the country—and will be remembered as cowards and opportunists, who put their own immediate political concerns above the fate of America.

In 1919, famed German theorist Max Weber gave a lecture to a group of idealistic left-wing students in Munich. It was a time of political shifts: Germany had lost the First World War, and revolution was in the air. For young students, politics must have seemed an attractive outlet for shaping a better world. Weber wanted them to be under no illusions, however. If salvation was what they wanted, for themselves, and others, they had the wrong idea. Politics is not just about doing what’s morally right, he warned them, in a lecture that would become his classic “Politics as a Vocation” essay. Or rather, what is morally right is not that straightforward in politics.

What “any person who wants to become a politician” needs to understand, said Weber, is an “ethical paradox” at the heart of politics: the contrast between the “ethics of conviction” and the “ethics of responsibility.” Those who act out of the “ethics of conviction,” according to Weber, do what they see as the morally right thing to do, independently of the consequences. Those guided by the “ethics of responsibility” try to anticipate the potential implications of their actions and take them under consideration before acting.

Many have criticized Donald Trump’s tepid reaction to the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi. Mainly, they’ve focused on his lack of moral indignation, i.e. lack of an “ethics of conviction”—his interest in keeping the Saudi relationship going despite the regime’s murderous activities. But what Weberians might note is that the president also hasn’t displayed any real ethics of responsibility.

Trump’s response to the death of Khashoggi has evolved over the past weeks, moving from statements on the importance of Saudi arms sales to criticisms of the regime. This has been, to some extent, a result of Saudi Arabia’s continuously evolving account of what happened. But Trump’s revised stance has also been a result of the public perception of this case, something that Trump himself admitted to, and lamented: “This one has caught the imagination of the world, unfortunately,” he said. “It’s not a positive. Not a positive.”

Downplaying moral conviction can be a good thing for a leader.In his interview with 60 Minutes, Trump came close to recognizing the atrocity of a government murdering a journalist over critical op-eds: “There’s something—you’ll be surprised to hear me say that—there’s something really terrible and disgusting about that if that were the case, so we’re going to have to see.” He then added, “We’re going to get to the bottom of it and there will be severe punishment.” But Trump’s recognition of the morally unpalatable nature of the journalist’s murder was coupled with a reminder of the enormous military order Saudi Arabia has placed with the U.S. Further concessions were also made: Khashoggi, after all, wasn’t a U.S. citizen, and the murder took place in Turkey, not on American soil. Trump has also said he believes the prince Mohammed bin Salman’s denial of involvement—that this was all carried out without his knowledge. True moral outrage was absent—probably unsurprising, as strong moral convictions are not something that Trump is known for, particularly when it comes to freedom of the press. The president has repeatedly called the media “the enemy of the people,” and recently applauded Republican Congressman Greg Gianforte for getting rough with a reporter.

Weber might point out that downplaying moral conviction can be a good thing for a leader. In fact, he criticized moralizing politicians, who he said “in nine out of ten cases are windbags,” self-satisfied with their own moral purity. More importantly, “they are not in touch with reality, and they do not feel the burden they need to shoulder”—to consider consequences, not just principles. For an illustration of that point, one need look no further than the Iraq War. According to reports from that time, the conviction that Saddam Hussein was “evil”—completely aside from the empirical question of whether he had weapons of mass destruction—trumped concerns about the possible complications and unwanted consequences of intervening in that area of the Middle East. Even though removing an evil dictator might have seemed a noble reason for going to war at the time, retrospectively, that seems a deeply irresponsible motivation, possibly even immoral, given the number of deaths, the power vacuum that allowed violent radical groups to proliferate, and the continuing instability of the country.

This brings us to Weber’s ethics of responsibility. It represents a down-to-earth pragmatism, one that takes into consideration the complexities of the world and the negative consequences that well-meaning actions might have.

Given the geopolitical

intricacies of the Middle East, there’s certainly a case

to be made that U.S.-Saudi relations need to be preserved for non-monetary

reasons— this security partnership provides some semblance of stability in the

region, that could otherwise erupt violently. On the other hand, this line of

argument would have to be weighed against the consequences that allying with

Saudi Arabia has had so far—including the famine a Saudi-backed alliance is

causing in Yemen. Even taking an “ethics of responsibility” stance against

Saudi Arabia does not provide easy options.

But this isn’t the sort of complicated political calculus the president has offered in place of moral indignation. Instead, the justification for being easy on Saudi Arabia has been couched in terms of financial loss—perhaps even on a personal level, as the president’s own business ties there have recently come under scrutiny. Trump’s caution over Saudi Arabia thus fails Weber’s definition of the ethics of responsibility as well: Weber explicitly stated that acting according to the ethics of responsibility was not the same as acting in pure self-interest.

On Thursday, news broke that Saudi Arabia’s public prosecutor was now acknowledging that Khashoggi’s murder was premeditated. This news will make it much harder for Mohammed bin Salman and his father, the king of Saudi Arabia, to maintain they were unaware of this plot. And it puts greater pressure on President Trump to choose a course of action.

Towards the end of “Politics as Vocation,” after having lectured the young, idealistic students in his audience about the moral compromises that a life in politics involves, Weber had a moment of idealism himself. Sometimes, even a politician with a keen sense of the ethics of responsibility, and an awareness of the potential consequences of their actions, can’t help but act on the basis of moral conviction. “This should be possible for any of us,” Weber said, “who is not dead inside.”

Unlike the American

president, who so far has displayed not so much a struggle between two ethical

compulsions as between public perception and calculated financial interest, at

least some members of Congress seem to

be taking the moral weight of the events seriously. There seems to be

bipartisan support

for at least exploring sanctions. In these times, having one branch of

government not be “dead inside” is perhaps all one can hope for.

The relationship between American Muslims and the Democratic Party is often described as a marriage of convenience. One of the best illustrations of this was the appearance of Khizr and Ghazala Khan at the 2016 Democratic National Convention. The Khans, parents of a U.S. Army captain killed in the Iraq War, didn’t exactly fit the liberal mold: Khizr Khan was a political independent who supported Reagan twice. But now the Khans were ardent Democrats. “Vote for the healer, for the strongest, most qualified candidate, Hillary Clinton, not the divider,” Khizr Khan said.

What choice did they have? Months earlier, Donald Trump had called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” This blatantly discriminatory proposal was part of a larger political campaign steeped in Islamophobia. Not even the parents of a war hero—the so-called good Muslims—were protected. As a result, more than three-quarters of Muslim voters cast their ballot for Clinton. The Muslim-Democratic alliance has only been strengthened in the wake of President Trump’s Muslim ban, which translated his xenophobic campaign promises into the law of the land. Today, Muslims constitute the “most Democratic-identifying religious group” in the country.

This is despite the fact that many Muslims continue to lean conservative, as Wajahat Ali Khan has pointed out in The New York Times. “[P]rivately, they adhere to traditional values, believe in God, and think gay marriage is a sin, even though an increasing number support marriage equality,” he wrote.

The Republican Party’s Islamophobia has turned Democrats and Muslims into strange bedfellows, while also masking differences that have emerged since the 2016 election. Interviews with Muslim leaders and activists, however, reveal that those differences often do not hinge on the Democratic Party being too progressive, but on the Democratic Party not being progressive enough. And far from treating the Democrats as a haven in troubled times, Muslim-Americans are starting to demand more from the only mainstream party that will have them.

For American Muslims, the challenges of living under a Trump administration started with the Muslim ban but are not limited to it. Trump’s first year in office corresponded with a 15 percent increase in hate crimes against Muslims in the U.S. The Trump administration’s foreign policy in the Middle East has also not sat well with most Muslims, including the administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and its decision to open a U.S. embassy there.

Trump has also used and legitimized anti-Muslim rhetoric as a campaign strategy in the midterms. A new report published by the group Muslim Advocates found “80 separate instances of clear anti-Muslim political rhetoric being directly used by candidates in 2017 and 2018 races.” A majority of the candidates using this rhetoric are Republican. And Trump himself tweeted last week that a migrant caravan approaching the U.S.-Mexico border—which has become a flashpoint for midterms races—had been infiltrated by “unknown Middle Easterners,” a clear attempt to inject an Islamophobic element into the issue. (He later admitted he had no proof for his claim.)

But Muslim-American political activity this campaign season has not been restricted to responding to these existential threats—to the contrary, it has been notable for its breadth, variety, and inventiveness.

This has been most evident in the midterms’ “blue Muslim wave,” in which more than 90 American Muslims ran for office across the country. Most lost in the primaries, but a few have made it onto the ballot in November, including two Muslim women running for Congress, Ilhan Omar in Minnesota and Rashida Tlaib in Michigan. What’s striking about Omar and Tlaib is that their platforms are squarely in the left wing of the Democratic Party. Like other progressive insurgents, they are committed to economic justice for working people, Medicare for All, abolishing ICE, and holding Democratic leadership accountable.

Muslim organizers are urging Muslim voters to think of their vote not simply as a means of ensuring their survival in this country, but also as a tool to shape a particular political vision. The Muslim grassroots organization MPower Change has been leading a nationwide get-out-the-vote and digital engagement campaign called #MyMuslimVote, partnering with local organizations in states with significant Muslim populations, including Michigan, Georgia, Virginia, and Texas. MPower’s campaign director Mohammad Khan explained that its voter mobilization strategy changed after the 2016 elections. Khan said, “We wanted our communities to think about voting in an aspirational way, we wanted to expand what people think of as Muslim issues. Muslims are not day-to-day thinking about how they’re going to fight terrorism, they’re thinking about the same things everyday that other people are thinking about.”

The results of the 2016 Democratic presidential primary contain some important clues on what these aspirations might be. In Dearborn, Michigan, a city where 40 percent of the population is Arab-American, Bernie Sanders beat Clinton with 59 percent of the vote. Some journalists were surprised that Arabs and Muslims had voted for a Jewish candidate, but it’s likely that voters were less interested in religion than the presence of a progressive, non-establishment candidate in the race.

According to a 2017 survey conducted by Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), “a substantial segment of Muslim respondents (roughly 30 percent) did not favor either of the two major party candidates” in the 2016 presidential election. Sanders’s appeal to Muslim voters is partly explained by the fact that, amongst major faith groups in the U.S., Muslims are the youngest and most likely to identify as low income. A 2018 ISPU survey revealed that one-third of Muslims find themselves at or below the poverty line. It should come as no surprise that, like other Americans who voted for Sanders, Muslims want better wages and affordable health care.

But Sanders also engaged with Muslims differently than Clinton did. Zohran Mamdani, board member of the Muslim Democratic Club of New York (MDCNY), said, “A lot of times in Democratic conversations, things are framed as looking at a whole community through terrorism and anti-terrorism and not seeing us as full, complex individuals who have a multitude of issues and deserve to be treated in a way that all other communities are.” The appearance of the Khans at the Democratic National Convention reinforced this framework, with its focus on a war that came shortly after 9/11 and that many Muslim Americans opposed.

One of the most powerful moments in Sanders’s campaign came at a rally in Virginia where a young Muslim student asked him how he would tackle Islamophobia as a president. Sanders responded by sharing his own Jewish family’s experiences with bigotry, placing Islamophobia in a larger context of American racism. In contrast, Clinton drew criticism from many Muslims, including MPower Change, after she blamed the 2016 attack at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, on “radical Islamism.” Muslims felt that Clinton’s use of this term, which President Barack Obama avoided, implied that Islam’s more than one billion followers were responsible for the beliefs and actions of a small minority.

Muslim-American political activity this campaign season is perhaps most evident at the local level. Muslims make up about 1 percent of the U.S. population, which means that, unlike other minority groups, they do not have the numbers to influence election outcomes on a national level except at the margins. But they do have the numbers to make an impact at the local and state levels.

For example, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) recently published a special voter guide for Muslim voters in Maryland. The guide includes a survey of candidates’ views on a variety of national and local issues that Maryland Muslims care about, including their position on whether public schools in areas with significant Muslim populations should close for the Muslim holidays of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. This is a particularly important issue for Muslims in Maryland because of the difficulties they faced in getting the state’s largest school district to start recognizing Muslim holidays in 2015.

One of the first groups to endorse Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in her upset primary victory of Rep. Joe Crowley in New York this summer was a community organization called Muslims for Progress. Based in New York City and Long Island, the organization was created in 2017 by Toufique Harun and Saema Khandakar, husband and wife, in response to the disaster of the 2016 election. Harun and Khandakar, who describe themselves as “complete and total political novices,” said that the group is focused on increasing Muslim involvement in politics and that it was inspired by Indivisible, a nationwide grassroots movement of locally led progressive organizations.

Ocasio-Cortez’s director of organizing is Naureen Akhter, a 31-year-old Bangladeshi-American Muslim who also co-founded Muslims for Progress. Akther heard Ocasio-Cortez speak at a rally in June 2017, and soon after started leading signature-gathering efforts in Queens to help her get on the primary ballot. Akhter was critical in shaping Ocasio’s engagement with the large Bengali and Muslim community in New York’s 14th Congressional District—Ocasio even made a special campaign video for Bengali voters in which she spoke in Bengali.

In 2017, Muslim and Arab voters in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bay Ridge rallied behind the first Arab candidate to run for city council, Reverend Khader El-Yateem. El-Yateem, a democratic socialist, ultimately lost the Democratic primary to Justice Brannan, but his presence on the ballot inspired unprecedented voter engagement amongst Arabs and Muslims, especially Arab and Muslim women.

In addition to supporting new progressive voices, Muslim organizers are focused on holding the Democratic Party accountable. MDCNY has an official endorsement process in which candidates have to fill out a questionnaire on a wide range of issues that matter to American Muslims. Mamdani said the purpose of this process is to “distinguish between those that simply talk about Muslims within this larger framework of ‘diversity is good and immigration is good’ and those who actually know that we don’t want broad platitudes.”

Harun from Muslims for Progress said that Muslims drawn to his group care more about issues than parties. “We work with the establishment candidates who fight for the issues, we work with grassroots candidates who work for the issues, we work with Republican candidates who work for the issues, we will work with anybody who fights for the right issues,” he said.

The focus on accountability has forced Muslim organizers to make difficult choices in the midterms. The New York attorney general primary between Public Advocate Letitia James and law professor Zephyr Teachout was especially challenging for MDCNY, since MDCNY had endorsed James in past elections. This time, the club endorsed Teachout after a tight vote amongst club members. James’s ties to Governor Andrew Cuomo were particularly frustrating for Muslim progressives, partly because Cuomo has never visited a mosque in his seven years as a governor.

Muslims, like other minority voters, expect more from the Democratic Party than it has given them in return. Khizr and Ghazala Khan’s appearance at the 2016 Democratic National Convention was a defining moment for Muslim visibility and inclusivity in American politics for many Muslims—but not all of them. Whether the Democratic Party can speak to the diversity of American Muslim politics will determine how deep this alliance will go.

Donald Trump’s presidency has sparked a rolling national discussion about the long-term vitality of America’s democratic system. Democrats are more than happy to talk about how his rise to power undermined the nation’s experiment in self-government, how his presence in the White House sullies it, and how his actions as president have imperiled it. But it’s unclear whether Democrats’ focus on acute threats to the republic’s long-term health extends to more chronic problems.

Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has been a sharp critic of Trump’s policies and behavior over the last two years. Last week, The Providence Journal’s editorial board asked him about his views on potential statehood for Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. Whitehouse responded with disinterest in the question for the island, then expressed opposition to its prospects for the district.

“I don’t have a particular interest in that issue,” Whitehouse said. “If we got one one-hundredth in Rhode Island of what D.C. gets in federal jobs and activity, I’d be thrilled.”

“Puerto Rico is actually a better case because they have a big population that qualifies as U.S. and they are not, as D.C. is, an enclave designed to support the federal government,” Whitehouse said. “The problem of Puerto Rico is it does throw off the balance so you get concerns like, who do [Republicans] find, where they can get an offsetting addition to the states.”

Whitehouse—whose comments caught wider notice on Thursday, prompting him to issue a statement saying that he would support statehood in both cases—is right that D.C. statehood raises some thorny questions for American governance. Placing the seat of federal power under a single state’s jurisdiction could be a constitutional crisis waiting to happen. (Imagine if D.C.’s power utilities cut off electricity to the White House and the Capitol during a dispute with the federal government, for example.) Ideally, the district’s residents could get congressional representation through something like the Twenty-Third Amendment. But since there’s no explicit constitutional bar to it, statehood is a feasible and reasonable solution to 700,000 Americans’ permanent lack of representation.

He’s also correct that Puerto Rico has a good case for statehood. The commonwealth’s 3.3 million Americans outnumber the populations of almost two dozen individual states, but dwell in a constitutional purgatory of sorts. Puerto Ricans enjoy a greater degree of self-government than a territory, but lack the sovereignty, legal stature, and electoral weight of a state. A grim recent example is the disastrous federal response after Hurricane Maria devastated the island last year and killed thousands of people. While congressional representation and a few votes in the Electoral College aren’t a panacea to the scars of colonialism and racism, the island’s residents have indicated in referenda that they would prefer it to the status quo.

Whitehouse’s response goes awry at two key points, however. The first is his dismissive approach toward the question of D.C. statehood itself. Senators need not be passionate or particularly interested in every political issue, but it’s striking that he’s so dismissive toward one of the most feasible ways that Democrats could chip away at the GOP’s current structural advantage in the Senate. After all, he spent the last few months staunchly opposing Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court. If two D.C. senators had been able to cast a vote, Whitehouse’s preferred outcome would have prevailed.

The second and perhaps greater error is Whitehouse’s concern that there isn’t an “offsetting addition” for Republicans. This may be an important practical hurdle to Puerto Rico statehood while the GOP controls the presidency or part of Congress. But it’s neither a legal requirement nor a moral necessity if Democrats eventually control all the political levers. It’s one thing for lawmakers to engage in a little horse-trading across the aisle to secure funding for a pet issue or pass a budget. It’s quite another to do it with millions of Americans’ right to self-government.

This approach is something of a tradition for top Democrats these days: unilaterally imposing limits on their ability to leverage an electoral mandate into lasting political change. Yearning for bipartisan buy-ins might have made sense in less polarized eras of American history. Now it just seems self-injurious for Democrats to seek it in the age of Trump. The GOP certainly isn’t operating under these rules. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the Senate’s master of realpolitik, isn’t going out of his way to add a few liberals to the pile of conservative forty-somethings that he’s shoveling into the federal courts. Republican secretaries of state like Kris Kobach and Brian Kemp haven’t bent over backwards to disenfranchise as many likely Republican voters as Democratic ones.

If Democrats retake power over the next few years, there are major steps they could take to strengthen American democracy. The Week’s Ryan Cooper made the self-evident but necessary argument in March that there’s “nothing wrong with strengthening America’s democratic institutions—making it simpler and easier for all Americans to vote and obtain political representation—in part because it would provide a partisan benefit.” At the top of his list was statehood for Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, followed by abolishing the legislative filibuster and passing a new, stronger Voting Rights Act. I’d add automatic voter registration and anti-gerrymandering reforms at the state level, too.

Indeed, there’s a similarly blunt clarity in the GOP’s current strategy. Without extreme partisan gerrymanders, widespread voter suppression, and strict anti-immigration measures, the conservative political coalition may no longer be electorally viable in an increasingly diverse country. Republicans therefore have a logical reason (albeit a morally flawed one) to oppose an American electorate that can fully impose its political will. The only real mystery is why any Democrats would oppose that, too.

This article has been updated to note Whitehouse’s statement on Thursday.

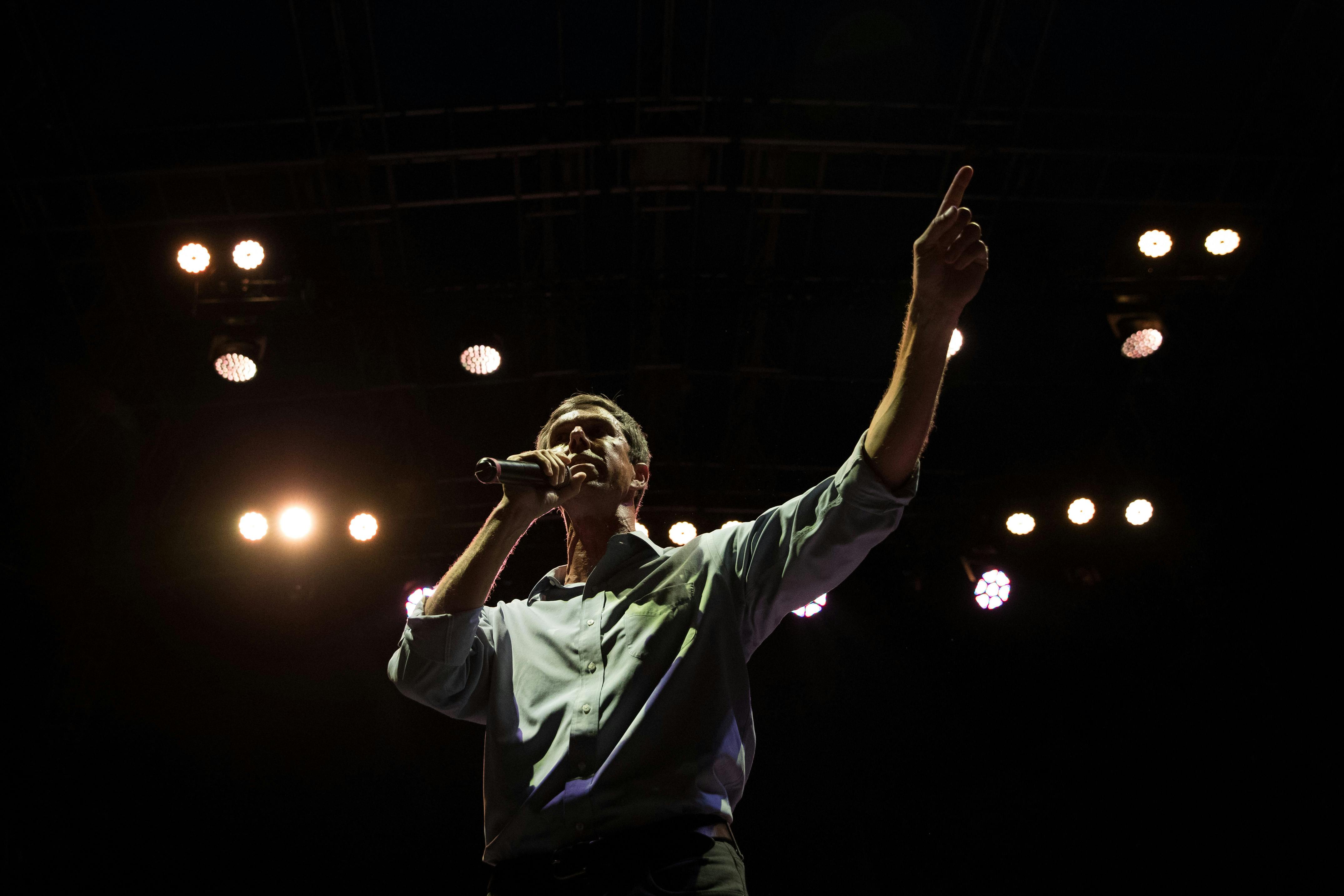

Donald Trump thinks he’s a rock star. Touring the country in support of Republican candidates, the president puffed out his chest and bragged about his ability to draw a crowd. “Do you know how many arenas I’ve beaten Elton John’s record?” he reportedly told Congressman Kevin Cramer, who is running to unseat Democratic Senator Heidi Heitkamp in South Dakota.

The crowds at my Rallies are far bigger than they have ever been before, including the 2016 election. Never an empty seat in these large venues, many thousands of people watching screens outside. Enthusiasm & Spirit is through the roof. SOMETHING BIG IS HAPPENING - WATCH!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 15, 2018While the midterms are the ostensible reason for Trump’s fall tour, Trump’s message is all about Trump. The candidates themselves rarely factor in. At a stop in Texas on Monday in support of his frenemy Ted Cruz, Trump paid cursory attention to the Texas senator and instead gave a rambling, lengthy speech that hit all of the same notes as his presidential campaign: fear-mongering over immigrants and crime, attacks on the media, spiteful discursions about his political opponents, and a deluge of lies. He did refer to himself as a “nationalist” for the first time, but that’s the only real news that his rallies have made for weeks if not months. Things have gotten so dull that even Fox News, which has covered his rallies extensively over the past three-plus years, is barely covering them.

Republicans who need the president’s help are also tiring of his schtick. “Most of the president’s hour-plus performances are one-man shows,” The New York Times’s Jonathan Martin and Maggie Haberman reported earlier this week. “Unlike with past presidents, the candidate of the hour is handed the microphone by Mr. Trump only briefly sometime during his monologue. Strategists involved in the campaigns have even started to time how long into his remarks it is before the president mentions the race in question and starts attacking the Democrat on the ballot, which is the 30 seconds of footage they most covet.”

But the sense of unpredictability that once permeated Trump’s rallies and public statements has long since disappeared. That’s out of necessity. His historically low approval ratings may be inching upward, but Republicans are still facing a blue wave in November. With few real accomplishments to run on, Trump is leaning on what he knows best: his greatest hits. But American voters may be tired of hearing them.

Ever since Trump became the favorite to win the Republican presidential nominee in the spring of 2016, pundits began speculating that a pivot was imminent. Surely, Trump’s platform, particularly on immigration, would have to be moderated for him to win the general election? Trump’s apparent willingness to break with GOP dogma on foreign policy and entitlements only reinforced this belief. But the great moderation never came in his campaign against Hillary Clinton. Instead, he stuck with the same setlist: demonizing immigrants and demanding a wall be built at the United States’ southern border; suggesting that Clinton was a criminal who should be jailed; inviting several women who had accused Clinton’s husband of sexual harassment and assault to a presidential debate. Trump never wavered from serving red meat to his Republican base.

After Trump was elected, again there was the assumption that Trump would moderate his behavior—that the presidency would force him to. In his first address to a joint session of Congress in February of 2017, Trump was uncharacteristically muted and sounded like, well, a normal president. He feigned humility and expressed faith in American diversity and promise. The pundits ate it up, apparently forgetting his “American carnage” inaugural address just weeks earlier. Van Jones infamously remarked on CNN that “tonight, Donald Trump became President of the United States.” Fox News’ Chris Wallace said the exact same thing. CBS White House correspondent Jonathan Karl, meanwhile, tweeted the speech was at “his most presidential—his most effective speech yet.”

Seven months later, the pivot was alive and well—despite the fact that, in the intervening time, Trump had fired FBI Director James Comey because of “this Russia thing,” blamed “both sides” after a white nationalist murdered a counter-protester in Charlottesville, tried to deliver on his promise to ban Muslims from entering the U.S., ordered an end to Obama-era legal protections for undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children, and so on. After Trump agreed to a funding deal with Democratic leaders Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, and suggested he was open to a deal to protect those undocumented children anew, Axios’ Mike Allen’s offer this take on the new Trump:

It’s like a fictional movie scene: A president wins election with harsh, anti-immigration rhetoric, then moves to terminate protections for kids of illegal immigrants. He’s ridiculed on both sides for his heartlessness — but cheered by a band of white voters who helped put him in office. Then he suddenly realizes he looks like a cold-hearted jerk—and starts musing about going farther than President Obama got in providing permanent protections to those children of illegal immigrants.

The deal for the DREAMers, who are still in limbo, never materialized. Trump resumed his usual habits of belittling the press, his opponents, and immigrants.

It took 18 months, but it seems, for the most part, that the pundit class finally caught on: With Trump, what you get is what you see. But that means that now Trump is oddly frozen in amber. While he occasionally talks up the tax cut, his Supreme Court nominees, and the economy, the bulk of his stump speeches in support of Republican candidates is made up of the usual Trumpian flourishes. In a rally for Nevada senator Dean Heller, Trump claimed that Democrats wanted to give undocumented immigrants the right to vote—and to give them cars, indeed Rolls Royces. He has continued to suggest, as he did in 2016, that, if put in power, Democrats would open the borders and abolish the Second Amendment. Despite unsuccessfully working to repeal Obamacare—and successfully working to weaken it—Trump has returned to 2016 claims that he will protect pre-existing conditions, as well as a host of other entitlements that the Republican Congress is hoping to undercut, including Medicare. (He also had the gall to claim that pre-existing conditions were imperiled by Democrats.) In Montana, he praised Greg Gianforte, who body-slammed a reporter from The Guardian in early 2017. “Never wrestle him, any guy that can do a body slam, he’s my kind of guy, he’s my guy,” Trump said of the congressman. And, two years after winning the presidency, he is still ranting about Hillary Clinton, now claiming that it was her campaign, not his, that colluded with the Russians.

The consensus among many in the media is that Trump’s repetitiveness, particularly on the issue of immigration, is tactical. “This pure brute force from Trump could work,” NBC News’ “First Read” briefing argued, “because there is no equal response from Democrats.” This “brute force” campaign built on fear-mongering, race-baiting, and conspiracy theories worked in 2018—why not now? Mike Allen concurred, writing that “immigration and stoking fear about Mexican immigrants propelled Trump to the White House.” Trump is claiming that he can set the terms for the midterms, unveiling a new battle plan at recent rallies: “This will be an election of Kavanaugh, the caravan, law-and-order and common sense.”

But Kavanaugh may be more of a boon for Democrats than Republicans—which could explain why Trump has emphasized the “Democratic mob” more than the Supreme Court justice. Immigration and “law and order” were the pillars of Trump’s 2016 campaign. While Democrats have struggled to combat the GOP’s immigration claims—or to put forth their own comprehensive solution—they may not need to. Health care, not immigration, has been the dominant issue of the midterms so far. Trump is retreating to familiar territory because he doesn’t have anywhere else to go, and Republicans are following him out of desperation. With an unpopular president and an even more unpopular agenda, these fear-based appeals may be Republicans’ only card. “Voters are motivated by fear and they’re also motivated by anger,” Newt Gingrich told The Washington Post. He was referring to the migrant caravan, but may as well have been describing the GOP’s election strategy.

Trump’s race-based appeals have been “effective for him politically,” Maggie Haberman pointed out on Twitter. But what worked in 2016 may not work in 2018, and not simply because Trump isn’t on the ballot, potentially depressing his supporters’ turnout. There’s a reason his rally venues have shrunken. He’s droning on about the same old things because he has very little to show for two years of unified Republican control of the government. His only legislative accomplishment is a tax bill that is hugely unpopular. His rallies in 2018 are a mix of ego-boosting and retreat to familiar territory. He has, two years into his presidency, become the political equivalent of a band that has been touring off the success of its first record for too long. The superfans are still buying it, but everyone else seems to be tuning it out.

It’s often said that the arc of history bends toward justice, but the arc of American history seems to bounce toward it instead. During Reconstruction in the 1860s and 1870s, the federal government campaigned to build a multiracial democracy in the South. That project’s defeat in 1877 then ushered in 90 years of Redemption, mass disenfranchisement, and American racial apartheid. Only in the 1950s and 1960s did the civil-rights movement and the Warren Court finally drag the United States into genuine liberal democracy.

Another dip now appears to be underway. President Donald Trump and the Roberts Court are poised to spark a Second Redemption—an era where federal enforcement of civil rights is no longer assured, where states are free to allow citizens to be discriminated against in housing and employment, where voting is a privilege instead of a right, and where a person’s access to goods and services can be restricted by the beliefs of total strangers.

The latest blow came over the weekend when the New York Times reported that the Trump administration is considering plans to roll back civil-rights protections for an estimated 1.4 million transgender Americans. Some federal courts have concluded that gender identity is covered by some existing federal laws that forbid discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived sex. But conservative policymakers in the administration disagree, arguing instead for a narrow definition of gender based on a person’s assigned sex at birth. The Justice Department asked the Supreme Court on Wednesday to overturn a Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in favor of a transgender worker, arguing that Section VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 doesn’t cover discrimination against gay, lesbian, and transgender Americans.

If the Trump administration succeeds, transgender Americans’ rights would rest on a patchwork array of state laws and local ordinances. Twenty states and the District of Columbia forbid discrimination on the basis of gender identity in housing, employment, and public accommodations. Another dozen states have limited legal protections for transgender people, while more than 15 states, mostly in the South and the Great Plains, have none.

The geographic division roughly matches the divide on other matters of gender and sexuality. A Washington Post analysis in September found that abortion would automatically become illegal in 14 states under current laws if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade. (Roughly a dozen others could follow suit depending on the state legislature’s makeup at the time.) Seven states allow pharmacists to refuse to fill a contraceptive prescription without referring it to another provider. Twenty-eight states don’t have anti-discrimination laws for gay and lesbian Americans in situations like housing and employment. Seven states explicitly allow discrimination in adoptions and foster care.

One of the most popular political cliches of the last few years is the notion that there are two Americas. But this is not simply an issue of political differences, of red states vs. blue states. Increasingly, there are two Americas in legal terms: one where citizens broadly enjoy a range of rights and legal protections, and one where they don’t. As the federal protection of civil rights falters, and the Supreme Court lurches to the right, those differences are becoming severe—with dire consequences for women, LGBT people, and many other disadvantaged citizens.

Perhaps the most well-known chasm is over abortion rights. In theory, a woman’s right to obtain an abortion is protected from undue state interference by the Constitution under current Supreme Court precedent. In practice, however, the procedure is increasingly hard to obtain in the nation’s rural regions due to state laws designed to force abortion clinics to shutter. Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming each have a single clinic that performs abortions, while Kentucky, West Virginia, and Utah have two apiece. A 2014 survey by the Guttmacher Institute found that one in five American women has to travel more than 43 miles on average to the nearest clinic.

Some of that distance can be attributed to simple geography and population density. But it’s also mediated by political forces. Louisiana, for example, is slated to have only a single clinic covering the entire state after the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a restrictive admitting-procedures law earlier this year. The Eighth Circuit recently refused to block a Missouri law that will leave a St. Louis clinic as the only available provider in the state. The confirmation of the staunchly conservative Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, replacing swing Justice Anthony Kennedy, raises the likelihood that similar measures will survive legal challenges, both in the lower courts and before the nation’s highest court.

Indeed, the most probable future for reproductive rights is a balkanized one: Women in blue states will still have access to the procedure, while women in red states will face a gauntlet of regulatory hurdles or have to travel long distances to obtain it nearby—if they can at all. Every year in the United Kingdom, hundreds of Northern Irish women who can’t obtain an abortion there cross the Irish Sea to have the procedure performed elsewhere in the country. The United States could see similar migrations by those with the ability to afford it in a post-Roe landscape.

In Michigan earlier this year, a pharmacist at a Meijer supermarket refused to fill a 35-year-old woman’s prescription for the drug misoprostal. The woman’s physician prescribed her the drug to complete a miscarriage she had suffered, but the pharmacist refused to fill it because he was Catholic, according to a letter sent to Meijer by the American Civil Liberties Union on her behalf earlier this month. He also refused to let another pharmacist handle it or to transfer the prescription to another pharmacy. “Unfortunately in Michigan, we don’t have an explicit state law that goes so far as to protect patients like Rachel,” an ACLU official told the Detroit Free Press.

The episode appeared to be a potential sign of things to come. The Roberts Court has taken a keen interest in religious-liberty exemptions in recent years, often ruling in favor of those who tell the court that their religious convictions run counter to state and federal laws. In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, the court’s five conservative justices, including Kennedy, sided with the craft store chain’s claims that the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate violated its religious freedom. The mandate required most American employers to offer insurance plans that covered contraceptives.

In its ruling, the court held that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, also known as RFRA, allows the owners of certain types of corporations to opt out of government regulations if those regulations run counter to their religious beliefs. Though individuals had been able to make RFRA claims under the law, the court had never held that it applied to closely-held corporations as well. The justices’ decision pleased religious conservatives who see liberal policy-making as antithetical to their faith. By applying it to companies, however, employees could have their access to healthcare shaped by religious beliefs that may not match their own.

Indeed, the ruling raised the specter that access to goods, services, and healthcare will be mediated by another person’s religious beliefs. Last term, the justices heard Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, case involving a Christian baker who refused to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple, citing his personal religious beliefs. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission found that the baker had violated the state’s anti-discrimination law by refusing serve the couple because of their sexual orientation.