Walmart has created its Overpowered gaming PC and laptop line.

Walmart has created its Overpowered gaming PC and laptop line.

President Donald Trump announced on Monday he would send 5,200 military troops to the southern border as a means of discouraging the 3,500-person migrant caravan inching its way toward the U.S. from Central America. It’s a transparently political ploy aimed at next week’s midterm elections—and an absurd one, given that the caravan is hardly a national security issue and certainly nothing that requires thousands of armed soldiers. But in hindsight, it was also inevitable. Trump and right-wingers turned the migrant caravan into an election issue with their hysteria about “unknown Middle Easterners,” leprosy, and the malevolent hidden hand of George Soros. Having manufactured a crisis, Trump is now attempting to show he’s solving it—with a meaningless show of force.

But as he was traveling the country fear-mongering about the caravan, Trump faced two crises that he had no control over. On Friday, Cesar Sayoc, a Trump fanatic, was arrested for allegedly sending more than a dozen pipe bombs to Trump’s favorite Democratic targets. A day later, an anti-Semite motivated by the relentless conspiracy-theorizing associated with the caravan murdered 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue. But Trump has barely paid lip service to these events. He called the massacre a “wicked act of mass murder” and “pure evil,” then used it to promote the death penalty and armed guards. As for the mail bombs, he complained that they were a political distraction:

Republicans are doing so well in early voting, and at the polls, and now this “Bomb” stuff happens and the momentum greatly slows - news not talking politics. Very unfortunate, what is going on. Republicans, go out and vote!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 26, 2018This fits a familiar pattern over the first two years of Trump’s presidency. He embraces crises of his own making, using them to cast political blame and to promote himself as a problem-solver. But he distances himself from those he cannot control, such as hurricanes, mass shootings, and administration scandals, because he is incapable of exhibiting moral leadership or accepting personal responsibility. Thus, next week’s elections are, among other things, a referendum on reality: Do voters believe Trump’s fever dream about an immigrant invasion of the U.S., or are they worried about real crises across the country?

Trump’s two most memorable and characteristic speeches were built on right-wing fantasies. In accepting the Republican nomination for president in 2016, Trump borrowed from Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign and called for a return to “law-and-order.” He tied Hillary Clinton to a supposed three-decade push to erase America’s borders, impoverish its citizens, and engulf the country in violence. “Every day I wake up determined to deliver for the people I have met all across this nation that have been neglected, ignored and abandoned,” Trump said. “The legacy of Hillary Clinton is death, destruction, terrorism and weakness.” The only way to reverse this crisis? Elect Donald Trump. “I alone can fix it,” he said.

Trump’s “American Carnage” speech at his inauguration in early 2017 was the capstone of his political project. Over the course of an hour, he portrayed America as a wasteland of abandoned factories for companies that had moved overseas; of supposed allies that were robbing America blind on trade and whose citizens were swarming into the country, stealing jobs; of terrorists on the march across the Middle East and Europe, readying strikes against the U.S. The only thing standing in the way of all of these forces was Trump. “This American carnage stops here and stops now,” he said. George W. Bush was right when he said the speech was “some weird shit.” Trump’s words ignored basic data about the economy, which was very much on the upswing, and about unemployment and crime, which were both on the decline. He inflated the danger of undocumented immigrants and the threat of terrorism. But the speech was a manifesto outlining Trump’s nascent political strategy, which was to create crises and then ride wall-to-wall media coverage—which often drowns out more substantive issues—as long as possible.

The firing of FBI Director James Comey, the withdrawal from the Iran deal, the renegotiation of NAFTA, the threats of nuclear strikes against North Korea, the levying of tariffs against some of America’s closest allies: Trump has repeatedly created crises where there were none or inflated existing risks. He has flouted the advice of experts of all stripes in order to engender the kinds of crises that he believes will resonate with his base. As The Atlantic’s David Graham argued earlier this year, Trump instinctively understands that he can only win when he’s seen as a last resort against extreme chaos. “Only in a moment of disaster would [voters] gamble on Trump,” Graham wrote. “Besides, Trump himself would be deadly bored if everything was going well.”

When presented with real carnage, whether in Pittsburgh or Puerto Rico, Trump balks. Recently, the bombs that had been sent to his political enemies were particularly frustrating because they minimized his ability to control the news cycle by saying and tweeting outrageous things. “The momentum was clearly on the Republican side,” Eric Bolling told The Daily Beast. “I don’t know that this is going to change anything, but certainly as much as President Trump is campaigning … for the news story to derail, I don’t know that that is frustrating him but I would suspect that that is something behind it.” Never one to take responsibility—or to lead on difficult issues, particularly ones that reflect poorly on his own supporters—Trump sees tragedies as liabilities to be minimized. Instead, he embraces a kind of political rope-a-dope, relentlessly flogging other issues until the media moves on to the next shiny object.

Trump has tried this repeatedly as the midterms approach. With media coverage dominated by the recent surge in right-wing violence and the expectations of a Democratic “blue wave,” he has ratcheted up his rhetoric. He suggested that he and congressional Republicans are prepared to pass a 10 percent tax cut for “middle-income” Americans and told Axios that he would revoke birthright citizenship by executive order, even though both are impossible to do before the midterm elections—and are close to impossible to do at all. He has suggested, again and again, that the Democratic “mob” will gut Medicare if elected, despite the fact that his administration has done much to damage entitlements and increase health care costs. Above all, he has flogged the caravan as an immediate threat to American safety and sovereignty.

For Trump and Republicans, the caravan is a potent metaphor for an America overrun by violent immigrants. As the caravan has made its way toward America, Trump has relentlessly followed its progress and now is deploying troops to the border—nearly twice as many as the U.S. has in Syria—in anticipation of its arrival. Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, deployed to Texas in a blatant publicity stunt, was asked by Fox News if American soldiers were prepared to use force to stop the caravan. “We do not have any intention right now to shoot at people,” she replied, to no one’s relief. Meanwhile, right-wing commentators and politicians have pushed the idea that billionaire Democratic donor George Soros, one of Sayoc’s targets, is funding the caravan.

Many Gang Members and some very bad people are mixed into the Caravan heading to our Southern Border. Please go back, you will not be admitted into the United States unless you go through the legal process. This is an invasion of our Country and our Military is waiting for you!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 29, 2018Typically, one would expect a more ebullient message from an incumbent president amid a robust economy, or at least a message built partly on the progress of a young administration. Trump has done exactly the opposite, building a campaign message around a series of fabricated national crises. He thrives on chaos and hate but acts aggrieved when confronted with the real-world consequences of his behavior. Asked about Sayoc at a Friday press conference, Trump deflected, saying, “There’s no blame. There’s no anything.” Then he spent the weekend blaming Democrats and the media for everything he could think of.

Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right nationalist who on Sunday was elected Brazil’s new president, has been called the “Brazilian Trump.” But he’s more extreme than that. His rhetoric is more explicitly violent and bigoted, and his rule threatens more than just the fourth-largest democracy in the world. The livability of the entire planet is at stake.

The Amazon rainforest, more than half of which is within Brazil’s borders, covers 4 percent of the earth’s surface and is a major regulator of the world’s climate. Its trees act as a sponge for carbon dioxide, absorbing the planet-warming gas from the atmosphere and re-emitting it as oxygen.

But Bolsonaro, according to HuffPost, “has committed to stop demarcating indigenous lands in the Amazon and further open the forest to mining interests. And he has pledged to loosen regulatory regimes over land-use and deforestation in the world’s largest tropical rainforest.” He also has strong ties to Brazilian agribusiness leaders who push for deforestation to make room for farming. He has said he’ll keep Brazil in the Paris climate agreement, but only if he can maintain control of the Amazon.

This is worth repeating over and over:

The most horrific thing Brazil's new president, Jair Bolsonaro, has planned is privatization of the Amazon rainforest. With just 12yr remaining to remake the global economy and prevent catastrophic climate change, this is planetary suicide.

Many are now worried that Bolsonaro’s presidency could result in an accelerated deforestation of the rainforest, which would mean huge increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide and an acceleration of climate change.

Scientists from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research wrote earlier this month that Bolsonaro could do “extreme” damage to the global climate. “Under Bolsonaro’s proposed policies, from 2021 to 2030, accumulated emissions from clear cutting Amazon forest would attain 13.12 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent,” they wrote. That number is staggering—equivalent to approximately 3 percent of global emissions, and approximately 20 percent of the remaining amount of carbon humans can release before catastrophic impacts begin.

Deforestation in Brazil has already played a huge role in the current climate crisis. In 2005, the country’s portion of the Amazon had the highest deforestation rate in the world. Because of that, Brazil is one of the largest contributors to global warming compared to other countries—either the fifth- or sixth-biggest historical emitter, depending on the estimate. Any successful effort to slow climate change thus must include the country, toward the goal of preserving its climate-regulating rainforest.

The country has proven itself capable of acting in the world’s best interest. In 2005, officials realized how crucial their rainforest was to preserving a livable climate, and decided to stop massive rates of deforestation. Less than a decade later, in 2014, scientists reported that the country had reduced its deforestation rate by 70 percent—all while increasing agricultural production of beef and soy, two of the region’s most lucrative biggest products.

Brazil’s deforestation reduction efforts likely bought the climate a little bit of time. According to National Geographic, the cuts had the effect of taking all the cars in the U.S. off the road for more than three years. And while the country’s progress eventually slowed—deforestation rates have been climbing since 2014—that time hasn’t run out yet. After all, around 80 percent of the Amazon has yet to be chopped down.

With the room twisting and her vision cloudy, Eleftheria Tombatzoglou touched her hand to the back of her head. It came away covered in sticky blood. “Blood, honor, Golden Dawn,” she heard her attackers chant as they bolted down the corridor and out the front door.

The Favela Free Social Center had been targeted before: graffiti, stones, Molotov cocktails. But February 25 was the first time that vandalism had escalated to a violent raid. And all the while, the Greek far-right group Golden Dawn was on trial.

The men had appeared as Tombatzoglou and five other activists were arranging chairs for the social center’s weekly meeting. Community members come every Sunday to help plan dance lessons, history courses, photography classes, and book club meetups for the coming week.

A man wearing a thick black jacket and motorcycle helmet strolled in and smiled at Tombatzoglou. It wasn’t until several more men in motorcycle helmets and dressed in black rushed in that she realized what was happening. “No way,” she said.

“You know what happens next,” one of the men replied. The room erupted. The attackers lit flares, smashed tables and windows, and threw smoke bombs. “Faggots,” one shrieked. “Cunts.”

One of the men turned to Tombatzoglou and pulled a tire iron from his jacket. “In Piraeus? Seriously?” he yelled while striking her, implying that the city was Golden Dawn territory—no place for leftists.

“Time’s up,” another shouted, signaling to the others that they needed to leave. The assailants fled as easily and quickly as they had entered minutes earlier, onto their motorcycles and off into Piraeus’s looping, narrow alleyways. As was the case with many attacks before it, the Favela raid bore all the marks of a well-planned operation.

Tombatzoglou, a 38-year-old lawyer, had half-expected to be targeted by the neo-fascist Golden Dawn party sooner or later. She is currently representing one of their victims in Greece’s ongoing multi-year trial against 69 Golden Dawn members. “I have read more than a hundred times the way they do attacks,” Tombatzoglou, who received eight stitches on her skull, told me a few weeks after the incident. “In a way, I was prepared. I know what these people are capable of doing, and I thought that sometime in my life I’d find myself in this situation.”

“The slower the process, the more they sense that they have impunity.”But another part of her was shocked: Why would the group risk such a brazen attack on a lawyer in a trial still underway?

Five years ago, on September 18, 2013, Golden Dawn member Giorgos Roupakias stabbed and killed Pavlos Fyssas, a 34-year-old anti-fascist rapper, outside a Piraeus café in full view of police officers. Outraged, Tombatzoglou became the Fyssas family’s civil suit lawyer in the broader trial the rapper’s slaying helped trigger.

Kicked off on April 20, 2015, the trial was predicted to span 18 months. It includes several civil suits and criminal charges against 69 Golden Dawn members, including the party’s core leadership, accused of operating a criminal organization, murder, racist violence, weapons possession, and money laundering, among other allegations. But with the trial dragging on and a verdict distant, Greek far-right groups, among them Golden Dawn, are reorganizing, carrying out further violence against refugees, migrants, political opponents—and individuals linked to the trial.

In early October, Tombatzoglou joined a dozen civil action lawyers calling for the trial to be sped up. The petition to newly-minted Justice Minister Michalis Kalogirou requested daily hearings in central Athens and asked that judges be freed up from other duties to focus on the case.

To date, the court has held more than 253 hearings, 250 prosecution witnesses took the stand, and the opposing legal teams entered into evidence tens of thousands of documents. Yet, with at least 230 defense witnesses waiting to testify and only eight to ten hearings taking place each month, it could now stretch into 2020.

“The slower the trial moves, the better it is for Golden Dawn to gain time and organize politically,” said Thanasis Kampagiannis, another civil suit lawyer in the trial. He believes the defense team is “stalling” with lengthy hearings examining irrelevant documents. “And the slower the process, the more they sense that they have impunity.”

The evening of the attack on Favela, Golden Dawn chief Nikolaos Michaloliakos issued statement denying his party’s involvement—much as he did on November 1, 2017, dismissing claims that his supporters attacked Evgenia Kouniaki, another civil suit lawyer, outside an Athens courthouse in broad daylight. The denials in both cases were far-fetched: Kouniaki’s attackers had been passing out Golden Dawn fliers only moments before they swarmed her, one of them slugging her in the face until her nose gushed blood.

Nearly four decades ago, in 1980, Michaloliakos, a 25-year-old with an impressive resume of political violence and criminal charges, founded the national socialist journal Golden Dawn. The journal’s publications have included brazen praise for German Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and his deputy Rudolf Hess, glowing profiles of American white supremacist outfits, and skepticism of the systematic extermination of Jews during the Holocaust.

Golden Dawn did not register as a political party until 1993. The newly-founded party was small in numbers but militant. Golden Dawn’s supporters subjected political opponents to a series of assaults that culminated in 1998 with a brutal attack on left-wing student unionists. That incident left 24-year-old Dimitris Kousouris in a coma for more than a month.

The unruly band of neo-Nazis remained largely confined to the margins of political life until its swift rise to national prominence during a pair of elections in 2012. As has been the case with far-right and neo-fascist outfits in several European countries in recent years, Golden Dawn coasted on a flood of anger from the country’s financial crisis and migration, first entering the parliament the following year. By then the party’s highly organized violence against migrants and leftists had already gripped Greece for years, yet the attacks accelerated after the electoral success. Party jackboots toppled migrant-operated stalls in open-air markets, military-like gangs mobbed leftists and anarchists caught walking alone, and flag-waving motorcades patrolled neighborhoods home to Asian and African immigrants.

The arrests of dozens of Golden Dawn members in the wake of Fyssas’s murder led to sharp slump in violence. With its leaders behind bars for 18 months of pre-trial detention, its members accused in the court, and its supporters facing anti-fascist pushback every time they took to the streets, Golden Dawn was isolated and weakened. Many Greeks hoped that the wave of pogroms had finally come to an end.

But despite most Greeks supporting the crackdown on the party, Golden Dawn repeated its electoral success in January 2015, gaining more than six percent of the vote and becoming the third largest party in the Hellenic Parliament. With Golden Dawn proving resilient and its fifteen lawmakers still using the parliament as a platform to amplify its ultra-nationalist message, the return of vigilante violence was imminent. Last year, hate crimes more than doubled, with incidents targeting people for their race, ethnicity, or national origin growing from 48 to 133, when compared to 2016.

Golden Dawn members protest the imprisonment of their members of parliament in 2013.Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty Images

Golden Dawn members protest the imprisonment of their members of parliament in 2013.Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty ImagesThroughout 2018, far-right attacks—not all of them committed by Golden Dawn—have persisted. During several rallies against the Greek-Macedonian name agreement, masked men beat journalists, flashed pistols, set anarchist squats ablaze, and desecrated Jewish memorials. In the otherwise sleepy agricultural communities neighboring Athens, young Greeks beat, stabbed, and bludgeoned Pakistani migrant workers. And on Greek islands, far-right protesters fired flares and lobbed bottles and stones at asylum seekers protesting poor living conditions in the ramshackle refugee camps.

When Naim Elghandour, the 64-year-old Egyptian-born president of the Muslim Association of Greece, received a grim anonymous phone call at home on January 18, the caller identified himself as member of Crypteia, a shadowy neo-Nazi group that garnered international media attention after attacking an Afghan family’s home in November 2017. “We are the group that kills, burns, hits, and tortures immigrants, mainly Muslims,” said the voice on the other end of the line.

Because he was at the time preparing to deliver an eight-hour testimony about Golden Dawn’s attacks on Greece-based Egyptian fishermen in the party’s trial, Elghandour found the timing suspicious. The following morning, he learned that at least three other civil society groups linked to the Golden Dawn trial had received the similar phone calls. “The police need to act because they know very well who these people are,” he told me. “They are an enemy of everyone, of humanity.”

And in early March, Greek counter-terrorism police arrested several members of Combat 18 Hellas, a national socialist group that had executed a three-year string of some 30 attacks on left-wing squats and Jewish cemeteries. During subsequent searches of the suspects’ homes, investigators discovered ammonium nitrate, Molotov cocktails, knives, shotguns, fascist literature, and small quantities of narcotics; they learned also that the Combat 18 Hellas included former Golden Dawn members.

Tombatzoglou has arrived at a bleak conclusion in recent months: More attacks are inevitable, including those meant to intimidate lawyers and witnesses in the trial. And the more elusive a guilty verdict seems, the more far-right attackers will operate with apparent impunity. The law and its ever-more-hypothetical ability to punish, at this point, have failed to check Golden Dawn activities.

“It’s in their nature,” she said of the Golden Dawn party. “They cannot exist without violence. There is no point in being a member of this party without the violence.”

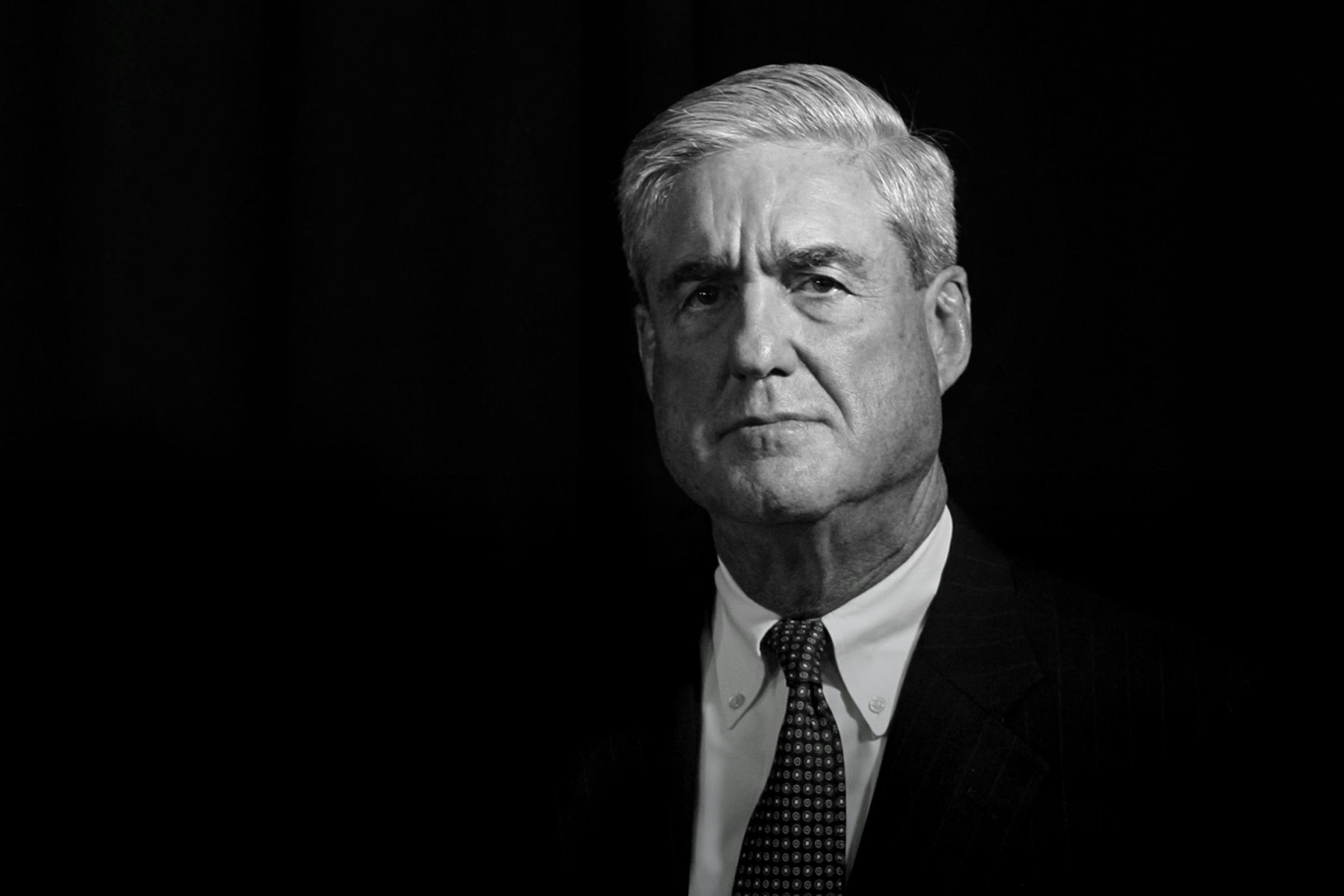

Here’s what the post-midterms world might look like: Democrats control the House by a decent margin. But they pick up just one seat in the Senate, allowing Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to exploit that more powerful legislative body to guard the White House. (Both electoral outcomes are likely, according to predictions.) Then, before special counsel Robert Mueller has the chance to reveal any of the work his team has been quietly doing during the campaign season, President Donald Trump finds a way to end or severely curtail Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Trump’s boldest move would be to fire Mueller himself. Shortly after Mueller was appointed in May 2017, Trump’s team claimed that the special counsel had conflicts of interest—claims that Trump might use to justify firing him. More recently, Trump has complained that the investigation—which by special counsel standards has barely begun—has gone on too long. If Trump is planning on firing Mueller, he’s most likely to do it right after the election, since it will take two months before the new Congress is sworn in and any political consequences will be delayed.

If Trump does not want to fire Mueller directly, he could derail the investigation in a couple ways. He could replace Mueller’s supervisor, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein. Rosenstein has forced Mueller to spin off unrelated parts of the investigation, but for the most part has permitted Mueller to proceed as he wishes, much to the chagrin of the White House. If Rosenstein were fired and no other staff shake-ups were made, his automatic replacement would likely be Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who has previously accused the FBI of overreach and claimed that former FBI Director James Comey, who was fired by Trump over the Russia affair, had shielded Hillary Clinton from possible prosecution. Democrats worry that an empowered Francisco could fire Mueller himself.

Alternately, Trump could convince Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has recused himself from the Russia investigation, to resign. Trump could replace him immediately with either Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar or Department of Transportation General Counsel Steven Bradbury, both Senate-approved officials who could take over temporarily under the Vacancies Reform Act. Both are reportedly under consideration to replace Sessions; both could fire Mueller if named attorney general.

Finally, Trump might even carry out a Wednesday Morning Massacre, working his way through the Department of Justice until someone decides they’ll back a claim that Mueller has engaged in misconduct—then use that accusation to justify firing him directly.

That would leave the new Democratic majority in the House as the chief means of carrying on the Mueller investigation. What could Democrats actually accomplish?

There are three main elements to a Mueller-less Russia investigation: 1) what Democrats could investigate whether or not Mueller is fired; 2) what they would be missing if Mueller were to be axed; and 3) what Democrats can salvage from an aborted investigation. Let’s take them in turn.

Democrats can call a whole lot of witnesses.In a recent op-ed in The Washington Post, Rep. Adam Schiff of California promised that if he were to become chair of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence under a Democratic majority, the committee would provide “a full accounting” of Russia’s entanglements with the Trump campaign and Trump White House.

He said the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, under Rep. Elijah Cummings’s leadership, would address how Trump “is profiting off the presidency,” indicating that that committee would investigate Trump’s possible violation of the Emoluments Clause, which prohibits the president from receiving payments from foreign governments. These payments may include those made to Trump’s inauguration committee, some of which came from Russian donors.

Schiff also suggested that the House Judiciary Committee would focus on “potential abuse of the pardon power [and] attacks on the rule of law,” which could include Trump’s daily attacks on the FBI, his tampering in FBI investigations, and the pardons he reportedly floated to his former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn and one-time campaign chief Paul Manafort, before both entered plea agreements and started cooperating with Mueller.

If Democrats win the House, Rep. Adam Schiff will likely play a central role in the House’s investigations into Russia’s role in the 2016 election.Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

If Democrats win the House, Rep. Adam Schiff will likely play a central role in the House’s investigations into Russia’s role in the 2016 election.Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesSchiff suggested his own committee would examine Russian financial influence over the president, which could cover Trump’s various business dealings in Russia. But it’s also likely that the Financial Services Committee, under Rep. Maxine Waters of California, would conduct much of that work.

In March, Schiff and the other Democrats on the Intelligence Committee released a status report naming witnesses Republicans had refused to call in their own cursory probes into Russia’s ties to the White House. These witnesses included White House aides Stephen Miller and Keith Kellogg, as well as former administration officials like former Chief of Staff Reince Priebus and K.T. McFarland, who served under Flynn.

Between them, these witnesses could provide more insight into the Trump campaign’s interest in pursuing a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, as well as into whether Russians were offering stolen emails from the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee in exchange for such meetings. The witnesses could also shed light on Trump’s personal involvement in Mike Flynn’s reassurances to Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, during the presidential transition in December 2016, that the Trump administration would seek to reverse Obama-era sanctions on Russia.

Schiff said he could also call Roman Beniaminov, who worked with Rob Goldstone, the music promoter who first set up the Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 in which Donald Trump Jr. sought to obtain dirt on Hillary Clinton. Beniaminov learned in advance that Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya would be dealing “some negative information” on Clinton.

Democrats would also call witnesses related to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which the Trump-affiliated firm gained access to the data of millions of Facebook users. Those witnesses could provide insight into how the Trump campaign exploited Facebook’s personal data to suppress certain kinds of voters in 2016. The legal concern here is two-fold: first, whether Cambridge Analytica employees from the U.K. worked for Trump illegally in the United States; second, whether Trump’s PAC, where some of those employees worked, coordinated improperly with the campaign. Given reports that Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix had discussions with billionaire Trump supporter Rebekah Mercer about optimizing the release of the emails stolen by Russia, Democrats would also inquire whether Cambridge Analytica exploited data stolen by Russians.

Perhaps the most incendiary testimony could relate to how Russians Aleksandr Torshin and Maria Butina, with the assistance of Republican operative Paul Erickson, used the National Rifle Association as a vehicle to draw the Republican Party closer to Russia. While Butina was arrested in July and Erickson is reportedly under active investigation, court documents relating to Butina’s prosecution describe Rockefeller heir George O’Neill Jr.’s active cooperation in Butina’s operation, down to his learning about Putin’s personal approval for the effort to host a series of “friendship and dialogue dinners” at which Russians could foster pro-Russian policies. “[A]ll that we needed is <<yes>> from Putin’s side. The rest is easier,” Butina wrote O’Neill in March 2016.

In the March plan, Democrats also said they would compel more information and testimony from witnesses that Republicans had let off easy. For example, the report lays out how both Donald Trump Jr. and Trump’s former campaign chair Corey Lewandowski refused, in past appearances before the Intelligence Committee, to describe communications pertaining to the June 9 meeting in Trump Tower.

The report also calls for more materials from the president’s former lawyer Michael Cohen pertaining to a 2016 bid to brand a Trump Tower in Moscow that continued well into the election year. And it argues that Erik Prince, the former head of the private security firm formerly known as Blackwater, must fully explain his meeting in the Seychelles with the head of a Russian investment firm, Kirill Dmitriev. Reporting since Prince testified to the committee in November 2017 suggests Prince lied about the meeting being an effort to set up a backchannel between Trump’s team and Russia.

Democrats have also promised to subpoena Twitter, WhatsApp, Apple, and the Trump Organization to learn more about communications that might be part of a conspiracy. For example, they’d like to obtain records showing which people, including Trump associates, communicated with Russian military intelligence mouthpiece Guccifer 2.0 or WikiLeaks, the outlets that released the Clinton and DNC emails stolen by Russia. In addition, Democrats would like to learn whether Trump associates communicated using encrypted messaging applications—messages that might have been missed in prior records requests.

So Democrats have a fairly robust plan for the investigations they’ll conduct if they win a majority in the House. But even that would only scratch the surface.

Democrats don’t have Mueller’s investigative prowess.The steps laid out by Schiff don’t account for what happens if Mueller is fired before finishing his investigation. That’s a problem because, at every step of his probe, Mueller has identified key players in Russia’s 2016 election operation that no one, including members of Congress, had yet discovered.

A few examples: A rural California man, Richard Pinedo, sold Russian internet trolls the identities they used to sow division among voters on Twitter and Facebook during the election—a role only disclosed when Mueller indicted the Internet Research Agency, a Russian troll farm based in Saint Petersburg. That same indictment described, but did not name, three Trump campaign officials in Florida who interacted with Russian trolls organizing a “Florida Goes Trump” rally in August 2016. (Those three people have never been publicly identified, and if they’ve been interviewed by any congressional committee, that fact remains secret.)

Meanwhile, Sam Patten, a Republican lobbyist, started cooperating with federal prosecutors a good three months before it was publicly reported. Patten was the partner of the Russian-Ukrainian consultant and suspected Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik, who interacted with Paul Manafort during the Trump campaign.

The most visible signs of Mueller’s investigation since February pertain to longtime Trump hatchet man Roger Stone, and yet where that aspect of the probe might lead remains a mystery. Trump campaign aide Sam Nunberg, Stone assistant John Kakanis, Stone social media adviser Jason Sullivan, Stone associate Kristin Davis, radio host Randy Credico, and conspiracy theorist Jerome Corsi—all appeared before Mueller’s grand jury.

Longtime Trump aide Roger Stone is an integral, if mysterious, figure in Mueller’s probe.John Sciulli/Getty Images for Politicon

Longtime Trump aide Roger Stone is an integral, if mysterious, figure in Mueller’s probe.John Sciulli/Getty Images for PoliticonMueller’s team also interviewed Ted Malloch, an associate of the British anti-immigration firebrand Nigel Farage. They questioned Trump aide Michael Caputo, while Stone aide Andrew Miller is currently fighting a grand jury subpoena in the District of Columbia Circuit Court. By May 25, at a time when just four of his associates had publicly revealed their testimony, Stone said eight of his associates had already been contacted by Mueller’s team. (Another witness against Stone received a subpoena but has never been publicly identified.)

While public reports have focused on questions about Stone’s interactions with Guccifer 2.0 or WikiLeaks, some of the Mueller team’s activity may relate to Stone’s dirty election tricks, which were funded by dark money groups. It’s unclear how such fundraising might relate to allegations that Stone cooperated with Russia. So even for the part of the Mueller investigation that has been most public, there are big gaps in the public record—gaps that committees in the House might not be able to close.

And that’s just witnesses. Mueller has also obtained a great deal of records and communications that no committee in Congress is known to have obtained. As one example, on March 9, Mueller obtained search warrants for five AT&T phones, having shown probable cause those phones included evidence of a crime. At least one of those phones belonged to Paul Manafort (which is how details of the warrant became public), but the identities of the other people who had their phones searched remain undisclosed.

Then there’s the money angle. Buzzfeed has done great reporting on Suspicious Activity Reports on bank transfers associated with the Russian investigation. It has also raised questions about whether Treasury has cooperated with the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the one committee that requested financial records relating to the investigation. But there’s no sign any committee in Congress has examined Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency transfers—financial flows that have figured prominently in Russia’s campaign disruption efforts. If the Mueller investigation is sidelined, congressional investigators might need to access the secret connections Mueller’s team has spent 18 months discovering.

How would they go about doing that?

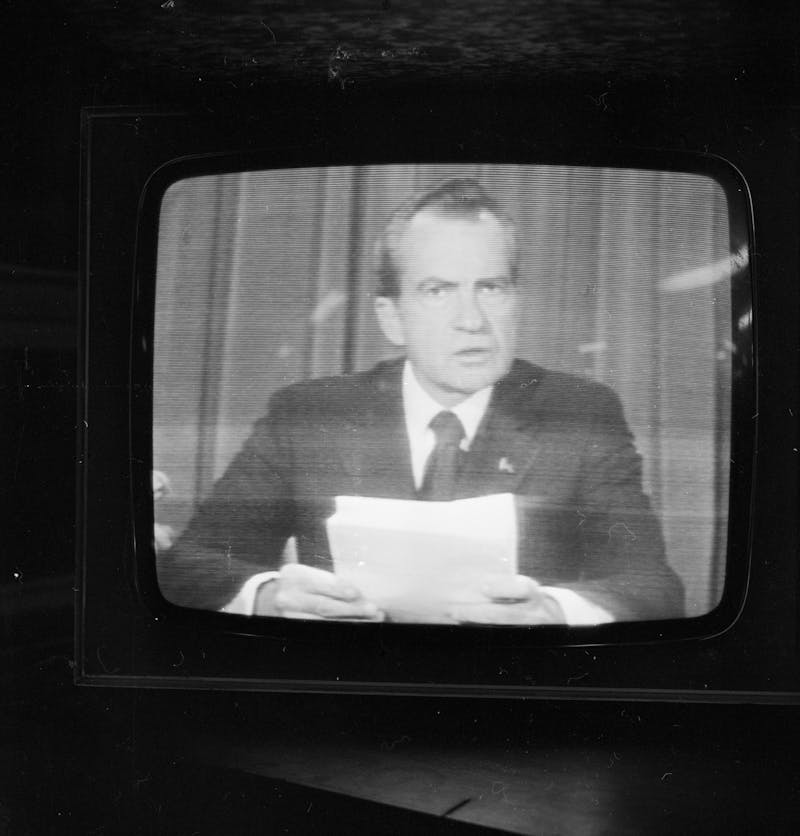

Democrats can use a Watergate playbook.House Democrats might follow the precedent set during Watergate—the last time that a president tried to thwart an investigation into election corruption by firing the Department of Justice officials conducting it.

Mueller’s activities thus far have been laid out in plea deals and highly detailed “speaking” indictments, which provide far more information about the actions involved than strictly necessary for legal purposes. But according to the regulation that governs his appointment, at the end of his investigation Mueller must also provide the attorney general with “a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the special counsel.” Also upon completion of the investigation, if the attorney general overrules an action Mueller wanted to take, he or she must notify the chair and ranking members of the Judiciary Committee.

It’s not clear what, within the scope of the regulations, would happen to such a report in the scenario laid out here, where Mueller got fired on some trumped-up claim of improper action. The only thing that would necessarily get shared with Congress is the report on why the attorney general had overruled Mueller, which wouldn’t necessarily include details of what else Mueller had discovered. Indeed, Neal Katyal, the former Obama administration lawyer who wrote the special counsel regulation under which Mueller operates, recently advised Rosenstein to provide a report to Congress before a meeting with Trump at which he might have been fired.

But Rosenstein might not permit such reports under department regulations. Rosenstein has refused to share information on the investigation in the past, citing the Department of Justice policy on not confirming names of those being investigated unless they are charged. And thus far, even Republicans attempting to undermine the investigation have not sought investigative materials from Mueller, instead focusing on the FBI investigation up to the time when Mueller was hired on May 17, 2017. That’s partly because under rule 6(e) of grand jury proceedings, information can only be shared for other legal proceedings (such as a state trial or military commission).

Yet a Watergate precedent suggests the House could obtain the report if Mueller were fired.

A Watergate precedent may be the key to protecting the Mueller investigation.Pierre Manevy/Express/Getty Images

A Watergate precedent may be the key to protecting the Mueller investigation.Pierre Manevy/Express/Getty ImagesSome Freedom of Information Act requests have recently focused attention on—and may lead to the public release of—a report similar to the one Mueller is mandated to complete. It was the report done by Watergate prosecutor Leon Jaworski, referred to as the “Road Map.” The Road Map consists of a summary and 53 pages of evidentiary descriptions, each citing the underlying grand jury source for that evidentiary description. In 1974, Jaworski used it to transmit information discovered during his grand jury investigation to the House Judiciary Committee—which then used the report to kickstart its impeachment investigation.

Before Jaworski shared the Road Map, however, he obtained authorization from then-Chief Judge John Sirica of the D.C. Circuit Court. In Sirica’s opinion authorizing the transfer, he deemed the report to be material to House Judiciary Committee duties. He further laid out how such a report should be written to avoid separation of powers issues. The report as compiled by Jaworski offered “no accusatory conclusions” nor “substitute[s] for indictments where indictments might properly issue.” It didn’t tell Congress what to do with the information. Rather it was “a simple and straightforward compilation of information gathered by the Grand Jury, and no more.” Per Sirica, that rendered the report constitutionally appropriate to share with another branch of government.

If Mueller—whose team includes former Watergate prosecutor James Quarles—were fired and he leaves any report behind that fits the standards laid out here, this Watergate precedent should ensure it could be legally shared with the House Judiciary Committee.

Can Trump do anything to stop them?The D.C. Circuit Court recently heard a case, McKeevy v. Sessions, on whether judges can release historic grand jury materials. Chief Judge Beryl Howell, who is presiding over the Road Map FOIAs as well as the Mueller grand jury, has stayed the Road Map FOIA to await its results. But McKeevy is a request for public release of grand jury materials, rather than disclosure to a government body with the constitutional duty to conduct its own investigations. As such, it probably wouldn’t affect the Watergate precedent.

So if Trump challenges the conveyance of Mueller’s report to the House Judiciary Committee, he would be making an argument not even Richard Nixon made. It is also an argument that the U.S. v. Nixon precedent—which held that due process limits the president’s claims of privilege—likely would not support.

Still, Trump will have one more way to stall, though probably not kill, House efforts to pick up where a fired Mueller left off. Under current House rules, committee chairs have the authority and the majority votes to issue subpoenas; if Democrats win a majority, they could even set new rules in the new Congress permitting committee chairs to issue subpoenas by themselves. But because the Department of Justice traditionally enforces subpoenas, congressional committees led by the opposition party have traditionally struggled to enforce subpoenas they do issue, especially for White House officials. That would be doubly true if Trump replaced Sessions with someone even more interested in obstructing real accountability for the president.

Even under Republican control of Congress, Trump officials have avoided or sharply limited their testimony by suggesting executive privilege might cover their testimony—without actually making Trump invoke it. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats and then-Director of National Security Agency Mike Rogers dodged testimony in this fashion, before ultimately testifying in a session closed to the public. More egregiously, former White House Communications Director Hope Hicks and Lewandowski refused to answer some of the questions posed by the House Intelligence Committee, notably declining to share information on the presidential transition.

Given two recent precedents—forcing the testimony of George Bush’s White House Counsel Harriet Miers (and consigliere Karl Rove) in the investigation into the firing of U.S. Attorneys and the cooperation of Barack Obama’s Attorney General Eric Holder in the investigation into the Fast and Furious scandal—a Democratic House will likely be able to compel cooperation from witnesses, even if it might take a while.

At a fundraiser in July, Rep. Devin Nunes, the Republican who thwarted all of Schiff’s investigative ambition on the House Intelligence Committee, explained that unless the Russian investigation were stopped, then the only way to thwart it would be for Republicans to retain the majority in the House. “We have to keep the majority,” he said. “If we do not keep the majority, all of this goes away.”

It might take time and a whole lot of litigation for the Mueller investigation to come to light. But Nunes may well prove to be right.

Several prominent conservatives initially responded to a wave of mail bombs sent to President Donald Trump’s critics last week with literal disbelief. “Fake bombs, fake news,” Lou Dobbs, a Fox Business News anchor, wrote on Twitter. “Who could possibly benefit from so much fakery?” On Twitter last Wednesday, Turning Point USA’s Candace Owens opined that “the only thing ‘suspicious’ about these packages is the timing” and suggested it was a leftist plot to win the midterms. She deleted those tweets, and two days later hosted an event with the president.

The bombs targeted the Obamas and the Clintons, multiple black lawmakers, top Democratic donors, former intelligence officials who have criticized Trump, and CNN—all of whom Trump and other top Republicans have regularly attacked. But many on the right refused to draw the obvious connection. “Republicans just don’t do this kind of thing,” Rush Limbaugh asserted on his radio show on Wednesday. Dinesh D’Souza, a conservative filmmaker, posted a fake Peanuts comic on Twitter that mocked the bomb’s purported origins. “Why do you say they were Democrat bombs?” Lucy asks. “Because NONE of them WORKED,” Linus replies.

Conspiracy theories have long flourished on the nation’s political fringes. Infowars’ Alex Jones and other right-wing conspiracy theorists have posited that the U.S. government orchestrated the September 11 attacks and that gun-control advocates carried out school shootings to further their agenda. Trump himself became a leading figure on the American right by questioning whether Barack Obama was born in the United States. But last week’s wave of outright denial by conservatives was still stunning by modern standards.

There’s a grim historical precedent in America for such aggressive skepticism of the causes of political violence. Today it’s universally recognized as historical fact that the Ku Klux Klan was responsible for a reign of terror throughout the South during Reconstruction. But many contemporary newspapers and politicians openly doubted the truth about the Klan’s purported mission, its crimes, even its very existence. The various motivations for this campaign of denialism are all too familiar today—and more worryingly, it worked.

Elaine Frantz Parsons, a historian who studied the organization, noted in her 2015 book, Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction, that Klan denialism shaped public perceptions of the group as well as the responses to it. While journalists and federal officials went to great lengths to document the group’s atrocities, “the national debate over the Klan failed to move beyond the simple question of the Klan’s existence,” she wrote. “Skepticism about the Ku-Klux even in the fact of abundant proof of the Ku-Klux’s existence endured and thrived, perhaps because people on all sides of the era’s partisan conflicts at times found ambiguity about the Ku-Klux desirable and productive,” Parsons wrote.

There was overwhelming evidence to refute the denialists’ claims. Klansmen routinely engaged in murder, rape, and other forms of violence that left behind scars, corpses, and witnesses. Larger cells carried out massacres and skirmished with local militias and federal troops. The Justice Department, which was founded in 1870 to enforce federal anti-Klan laws, prosecuted and convicted hundreds of its members in public trials.

But still the denial persisted. Perhaps the most dramatic example came in 1872, when a joint congressional committee published a thirteen-volume report on Klan activities and trials in the Southern states. Lawmakers questioned witnesses in multiple states and drew upon testimony from them and the anti-Klan trials, aiming to produce a comprehensive and definitive account of the crisis. The majority report concluded that the Klan did exist, that many of its members had evaded punishment for their crimes, and that the “terror inspired by their acts, as well as the public sentiment in their favor in many localities, paralyzes the arm of civil power.”

The committee’s Democratic members, however, were extremely skeptical toward every claim of Klan violence that came before them. In their minority report, they ultimately took the head-spinning position that the South’s white citizenry were the real victims. Black freedmen and their white allies, who were being regularly murdered throughout the region, were cast as the real aggressors. “The atrocious measures by which millions of white people have been put at the mercy of the semi-barbarous negroes of the South, and the vilest of the white people, both from the North and the South, who have been constituted the leaders of this black horde, are now sought to be justified and defended by defaming the people upon whom this unspeakable outrage has been committed,” the committee members wrote. To white supremacists, building a multiracial democracy was tantamount to violence.

The episode underscored the stark partisan divide over the Klan, as well as the ways that Democrats had turned the group’s ephemeral nature against its opponents. “In this way, what was arguably the most ambitious investigative effort to that point on the part of the U.S. Congress, enormously expensive, time-consuming, and carefully arranged to be meaningfully bipartisan, was abruptly rejected by Klan skeptics in its entirety,” Parsons wrote. “It is hard to imagine what possible body of evidence might have stood up to such summary dismissal.” Southern Democratic newspapers, she noted, also took part in the campaign of denial.

A Georgia paper screeched in November 1871 that the Klan “has existence only in the imaginations of President Grant and the vile politicians who have poisoned his ears with false and malicious reports... The reports of collisions between armed bands of Ku-klux and federal troops are utterly false, base, and slanderous fabrication, uttered for a purpose.” Rather than retreat and regroup as more evidence slammed their position, those who were invested in believing that there was not a pattern of extreme violence against southern Republicans stood firm. As the Daily Augustus Gazette reported summing up the Ku-Klux trials, “And now, after all this has been done, and after the expenditure of a vast amount of the public money, a skeptical public are less disposed than ever to believe in the existence of a Ku-Klux organization…. True, numbers of prisoners when brought to trial have confessed…. and there has been an unlimited supply of evidence to the same effect taken, but it could not deceive anyone who desired to know the truth of the matter.”

Klan denialism and skepticism took root in a civic soil that was primed to receive it. Americans in the post-Civil War era lived in a changing information ecosystem thanks to technological advances and logistical changes brought about by the conflict. The average citizen had access to a steady stream of information from newspapers, telegraphs, and word of mouth among an increasingly transitory public. Editors and newspaper owners still operated as partisan actors, Parsons noted, but the surge in newsworthy information forced them to decide what to print and what to omit. These changes gave some Americans a new reason to distrust sensational information that they came across and question why certain stories were presented to them.

Some Americans of the era may have genuinely struggled with the idea that such a group could exist. Others downplayed its acts or discredited its victims for political purposes: Democratic politicians and newspapers aimed to undermine President Ulysses S. Grant and the Radical Republicans to weaken support for their Reconstruction policies. Liberal Republicans, led by New York publisher Horace Greeley, turned toward Klan skepticism in their bid to reassert control over the party. And Northern journalists sometimes veered into sensationalism when covering the Klan’s acts, a habit that made it harder for Americans to distinguish between genuine accounts of Klan savagery and fictional ones.

“It was a particularly ugly display of human nature, and the worst thing about it was precisely that it was not in the least mysterious,” Parsons concluded. “Ku-Klux and their suffering victims were all too human and all too plainly visible to anyone who had the fortitude to look. Folding Reconstruction-era violence into the Ku-Klux, imagining it as spectral, ambiguous, and indeterminate, enabled Americans to turn away from that unjust reality and all of the political implications and obligations that it entailed.”

There is no official death toll for the era’s spasmodic violence, which continued through other groups following the Klan’s decline after federal enforcement peaked in 1872. Contemporary estimates ran high: Robert Smalls, a black congressman and hero of the Civil War, told South Carolina’s constitutional convention in 1895 that 53,000 African Americans had been murdered throughout the South since emancipation. What’s easier to ascertain is that assassinations, massacres, and intimidation by the Klan and other groups worked. “Reconstruction did not fail; in regions where it collapsed it was violently overthrown by men who had fought for slavery during the Civil War and continued that battle as guerrilla partisans over the next decade,” historian Douglas R. Egerton wrote in The Wars of Reconstruction. “Democratic movements can be halted through violence.”

Political violence by right-wing and white supremacist groups is nowhere near as widespread today, of course. But it still exists. Republican elected officials and conservative media outlets spent the Obama years downplaying the growing threat. In 2009, a Department of Homeland Security analysis warned about a possible uptick in right-wing violence after the Great Recession began. Republicans responded by successfully pressuring the department to rescind the report.

Trump’s election only emboldened the most extreme elements of American society, and he appears to welcome the phenomenon. He frequently signals to his supporters that his disavowals of white-nationalist groups and other right-wing racists are not genuine. After a white-nationalist march in Charlottesville turned deadly last summer, he declared that there were “some very fine people” on both sides. Political figures across the ideological spectrum condemned his remarks, but white nationalists responded with joy. David Duke, a former leader of the Klan’s modern incarnation, praised Trump for his courage.

The president’s rhetoric reached its logical conclusion on Saturday when a gunman murdered eleven Jewish worshippers at a Pittsburgh synagogue. Robert Bowers, the alleged killer, had invoked anti-Semitic conspiracy theories online. “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people,” he wrote on Gab, a social networking platform that’s popular among white nationalists, shortly before the massacre. “I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

HIAS, originally known as the Hebrew Immigration Aid Society, is a Jewish nonprofit group that helps bring refugees to the United States. It’s a common conspiracy theory among white nationalists that Jewish people are trying to replace America’s white population with nonwhite immigrants. Trump and his allies have espoused variants of this theory, often centered on Jewish billionaire and Democratic donor George Soros, who was among last week’s mail-bomb targets. The president has frequently hyped the migrant caravan traveling toward the U.S. as a purported threat to American security and even falsely asserted that “Middle Eastern individuals” were among the migrants, with the racist implication that they were terrorists.

Trump responded to Saturday’s shooting in Pittsburgh by condemning this “wicked act of mass murder” and anti-Semitism in general, but a day later he shifted responsibility for the bloodshed to mainstream news outlets.

The Fake News is doing everything in their power to blame Republicans, Conservatives and me for the division and hatred that has been going on for so long in our Country. Actually, it is their Fake & Dishonest reporting which is causing problems far greater than they understand!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 29, 2018Denial can take many forms. On Monday morning, as her boss faced accusations that he’s culpable for the violence, White House adviser Kellyanne Conway tried to craft an alternative explanation for it.

“The anti-religiosity in this country that is somehow in vogue and funny, to make fun of anybody of faith, to be constantly making fun of people who express religion, the late night comedians, the unfunny people on TV shows—it’s always anti-religious,” she told Fox and Friends. “These people were gunned down in their place of worship, as were the people in South Carolina a couple of years ago, and they were there because they’re people of faith, and it’s that faith that needs to bring them together. This is no time to be driving God out of the public square.”

Conway’s proposition is unmoored from reality. Dylann Roof, the young white man who murdered nine black parishioners in a Charleston church in 2015, left a racist manifesto online before the shooting. The common theme between these acts of violence is white nationalism, not late-night comedians.

In many ways, Trump is unlike any other president who came before him. But his approach to American politics is not wholly without precedent. There’s nothing new or special about his use of denialism, falsehoods, and bad-faith attempts to shift blame onto his political adversaries. Reconstruction’s failure shows that national campaigns to deceive and mislead the public about white-nationalist violence have worked before. This country is about to find out whether they will work again.

No comments :

Post a Comment