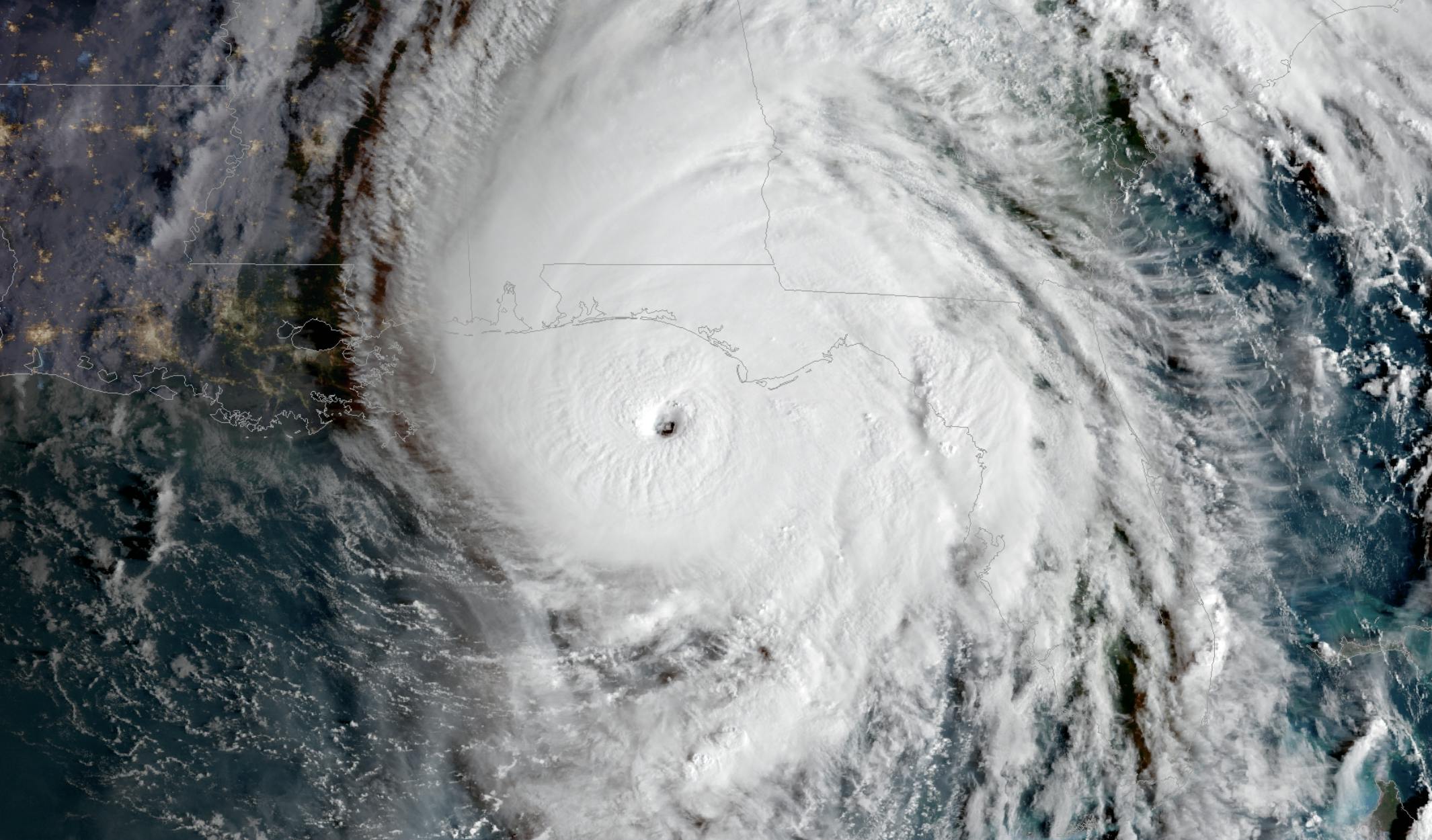

Hurricane Michael made landfall on Wednesday with winds of 155 miles per hour, just shy of Category 5 strength—the most powerful hurricane to hit Florida’s panhandle in recorded history. It will also serve as an “October surprise” in the upcoming midterm elections in Florida, where the state’s Republican governor, Rick Scott, is in a tight race for U.S. Senate against Democratic incumbent Bill Nelson.

Politically, the hurricane stands to benefit Scott far more than Nelson. As a sitting governor, Scott can more easily show leadership during a crisis, which voters are proven to reward. He’s been doing just that: The New York Times reported on Monday that Scott “has been darting from one county emergency operations center to the next for closed-door meetings and somber news conferences.” It’s a familiar and perhaps comforting sight for Floridians, as Scott has presided over three hurricanes and six tropical storms during his tenure. This week, Scott declared a state of emergency for 35 counties; activated 1,250 members of the Florida National Guard; and waived tolls to allow coastal residents to evacuate more quickly.

Nelson has less opportunity to show such leadership. As a sitting U.S. senator, he was empowered to ask President Donald Trump to declare a federal emergency in Florida—but other lawmakers did so, too. Nelson also can’t stage elaborate press conferences that compare with Scott’s. The Times reported that Nelson “tried to speak to reporters at the emergency management center in Tallahassee—the same place where Mr. Scott often commands the state’s attention—but was turned away because he was not there for official business.”

If Nelson has one advantage, though, it’s that he’s been trying to prepare Florida for big storms like Michael for years, by drawing attention to the impacts of climate change and calling for action. He’s proposed legislation to help coastal cities prepare for greater storm surge; held hearings on sea-level-rise; and advocated for strengthening building codes to withstand wind events. His opponent, on the other hand, “has done little over the years to prepare for what scientists say are the inevitable effects of climate change that will wreak havoc in the years to come,” according to The Washington Post. And Scott’s failure to prepare has had grave implications for Florida, “one of the states at greatest risk from rising sea levels, extreme weather events—including more-powerful hurricanes—and other consequences of a warming planet.”

In the past, Nelson has called out Scott for ignoring global warming. But the senator hasn’t been talking about climate change this week, amid Hurricane Michael, as Floridians on the Gulf Coast feel the consequences of Scott’s inaction. Why? Because doing so would invite accusations of politicizing a tragedy.

Both Nelson and Scott have sworn off campaigning during the storm, cancelling events and taken down negative ads. “This is not the time for politics,” Nelson told CNN on Tuesday.

This mutual agreement benefits Scott more than Nelson. The governor, dressed in “disaster casual,” can still engage in politics by repeatedly appearing on the television screens of millions of people, talking about how the state is going to weather the storm. At the same time, Nelson effectively has muzzled himself from showing how decisions Scott has made have worsened Michael’s impacts—at a time when that argument is most relevant to people in the state. The no-politics pact also insults voters, implying they’re unable to consider policy implications at the same time they’re digesting emergency information about a hurricane.

Nelson is far from the only Democrat avoiding climate change at a critical time for voters—and far from the worst offender, since he’s at least talked about the issue during his campaign. As the Times reported last week, “The vast majority of Democrats and Republicans running for federal office do not mention the threat of global warming in digital or TV ads, in their campaign literature or on social media.” Those candidates include Democrats running in districts hit hard by hurricanes Florence, Harvey, and Maria—three disasters that scientists have said were made worse by global warming.

Climate change is indeed a politically risky topic, owing to years of Republican claims that it’s not an existential threat to the planet, but a liberal conspiracy to regulate big industries out of business. Democrats in swing or conservative-leaning districts are understandably shy about calling Republicans liars, so instead they ignore the issue. It’s simply not worth taking the risk—especially on a topic that historically hasn’t even motivated liberal voters.

But historical motivations for voting are becoming less instructive as climate change worsens. Over the last year, millions of Americans experienced record-breaking extreme weather—500-year floods, devastating wildfires, powerful hurricanes. And because of the rise of attribution science, scientists have been able to quickly attribute details of these weather events to climate change. For most Americans, climate change has always been something that might happen in the future, but hasn’t happened yet. That reality is changing.

Democratic candidates who represent Americans affected by these historic weather events have a unique opportunity to adapt to this new reality, and highlight the consequences of climate denial on voters’ lives. Republicans might call them insensitive. But voters deserve lawmakers who would rather protect them from disasters than protect them from the truth.

In August 2008, just before the slow-moving financial crisis turned into outright panic, the secretary of the Treasury, Hank Paulson, traveled to the Summer Olympics in Beijing. At a private lunch with Chinese officials, he learned that members of the Russian government had been urging the Chinese to join them in selling off large portions of their holdings in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the multitrillion-dollar companies that supported (and still support) much of the American mortgage market. The goal, it seemed to Paulson, was to force the U.S. government into an unplanned emergency bailout of the two companies—or risk destabilizing the economy by making it impossible for people to get mortgages. “Whenever I envisioned the Russians selling, the knot in my stomach got bigger,” Paulson told me recently. (The Chinese, for their part, declined to sell.)

Shares in the two companies had been declining precipitously since late 2007, and even before Beijing, Paulson had been scrambling for a solution. The month before the Olympics, Congress, with urging from Paulson, had passed a law allowing the Treasury to make unlimited investments in Fannie and Freddie—a sort of first-strike doctrine in case Paulson needed to offset a crash. As Paulson told the Senate Banking Committee, “If you’ve got a bazooka and people know you’ve got it, you may not have to take it out.”

As the companies’ stocks continued to fall that summer, Paulson decided he was going to need the bazooka; he believed investors wanted assurance that Fannie and Freddie would not be allowed to fail. The problem was that the legislation, as written, gave the government the right to inject capital into Fannie and Freddie only until the end of 2009, which would not be long enough. So Paulson and his team took a little creative license. They devised a structure that in essence enabled the Treasury to invest in “perpetual preferred stock”—essentially loans with no date at which they had to be redeemed—from the companies to cover their losses for years into the future, as long as the deal to do so was struck by the end of 2009. The team at Treasury took what Congress had meant to be a temporary guarantee and transformed it into a permanent one.

In enacting the eventual bailout of the American financial system, Paulson—with Ben Bernanke at the Federal Reserve and Tim Geithner at the New York Fed—took his cue from leaders in other desperate times. “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation,” said Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, as America battled the Great Depression. “It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.” When Roosevelt was sworn in as president the following year, he tried not just “some” things, but a lot of them, passing landmark financial laws, some of which still govern banks in this country. In 2008, Paulson, Bernanke, and Geithner were even bolder and more persistent in their experiments. They didn’t always wait for Congress to give them permission. Instead, they stretched existing laws to their legal limit, and used new laws in ways that defied congressional intent.

All three argue that their actions prevented the Great Recession from spiraling into a Great Depression. That may well be. But if another crisis were to arise today, would Americans want today’s Paulson, Geithner, and Bernanke to take similar license?

Paulson has said that the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac takeover was his most important act at the time. But while it kept the mortgage market functioning, it did nothing to create calm. A week later, Lehman Brothers, the financial services firm, which had over $600 billion in debt, filed the largest bankruptcy in American history. Investors, alarmed at the collapse, began to pull their cash from money market funds, which provide financing for many businesses. A widespread run would send the economy into free fall.

So the Treasury got creative again. This time, the mechanism was the Exchange Stabilization Fund, a pool of money the Treasury is only supposed to use if the dollar comes under extreme pressure. This hadn’t happened, although one could argue, and Paulson did, that the potential demise of the U.S. economy would indeed cause the dollar “extreme pressure.” On September 19, the Treasury announced that up to $50 billion—nearly all of the ESF’s assets—would be made available to guarantee deposits in money market funds.

It didn’t stem the panic. The Dow Jones Industrial Average continued to plummet. On October 3, President Bush signed into law the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP. Again, Paulson and the others would do something Congress had not intended. Lawmakers thought that TARP would be used only to buy troubled mortgage assets from financial institutions. The specific language of the legislation, however, actually allowed the money to be used to buy just about anything, as long as Paulson and Bernanke deemed it necessary to protect the system. Almost two weeks later, on October 14, with the markets still deteriorating, the Treasury Department announced that $250 billion in TARP funds would go toward purchasing shares in banks instead of mortgage assets. When Paulson was asked if the Bush administration had misled Congress, he replied, in an echo of FDR, “I will never apologize for changing an approach or strategy when the facts change.”

That same day, the FDIC, at the urging from the Federal Reserve and the Treasury, took a step that involved a big stretch of existing rules. The FDIC announced that its fund, instead of exclusively guaranteeing the safety of depositors’ cash, would be used to temporarily guarantee the new debt issued by financial institutions that weren’t yet failing, including Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and smaller firms. A key argument was that if the fund was not used for this purpose, the banking system would fail, and the fund quickly would be emptied, leaving the FDIC unable to insure deposits at all.

And with that, the acute period of the financial crisis ended.

Ten years later, much of the debate about how the crisis was handled focuses on its specific winners and losers. Why save Bear Stearns and let Lehman Brothers fail? Why bail out wealthy bankers but not taxpayers? Many economists and academics agree that Paulson, Bernanke, and Geithner prevented a far worse outcome, but there is dissent. Dean Baker, senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, and the author of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, has long argued that warnings of another Great Depression were a “scare tactic,” and that had the government allowed firms to fail, “we could have quickly eliminated bloat in the financial sector and sent the unscrupulous Wall Street banks into the dust bin of history.” Others have argued that the banks should have been nationalized, wiping out shareholders and bondholders.

The failure of the argument that there had to have been a better way is it can never be resolved. People in power took the course they did, the economy didn’t collapse, and there is no way to know what would have happened otherwise. If Americans could do things again, in some parallel universe, would they want the government to take a different course, knowing that this one, however unfair, did not lead to a second Great Depression?

It may be academically interesting to debate the bailout, but it is ultimately beside the point. There hasn’t been much public discussion about what does matter, namely, how much flexibility there should be in a future crisis. There is less now than before. New regulations have made it so a future Treasury secretary would not be able to use the ESF in the same expansive way that Paulson did, and the FDIC can no longer issue blanket guarantees of bank debt without Congressional approval.

It’s possible that the Treasury and Fed won’t need so much flexibility in the future. The 2010 Dodd-Frank law requires U.S. banks to give regulators “living wills”—plans to dismember themselves in times of collapse. It also created an “orderly liquidation authority,” which is supposed to provide a process to liquidate, say, Goldman Sachs quickly and efficiently, with shareholders and creditors, rather than taxpayers, bearing the losses.

But there’s a real disagreement as to how “orderly” the process would be if multiple banks were failing all at once. The next crisis might unfold in ways the new rules and regulations haven’t anticipated. Fixing it with laws based on the last crisis is probably not the best approach. In any event, stopping a run probably would require taxpayer money—it is just about the only thing that has stopped bank runs since the nineteenth century.

According to a 2012 Harris Interactive poll, 84 percent of Americans oppose another bank bailout, and Pew data shows that trust in government has rarely surpassed 30 percent since 2007. This means that whoever serves as Treasury secretary or Federal Reserve chairman in a future crisis will face a daunting decision: Follow the laws as written and as Congress and the public intends, and let things play out—or forcefully attempt to shape a better outcome in the face of both legal and public opposition.

Last December, at the election-night watch party for Doug Jones in Birmingham, Alabama, LaTosha Brown and Cliff Albright were among the last to arrive. The founders of the Black Voters Matter Fund had worked throughout 2017 to register and turn out rural voters in the state for the former U.S. attorney’s long-shot U.S. Senate bid against evangelical stalwart and accused child molester Roy Moore. They had moved souls to the polls until they closed, then met up in Birmingham to join their fellow activists and Democrats.

“The people in there were quiet, hushed, waiting for the final results,” Brown told me. “These being Alabama Democrats, nobody could actually believe their own eyes, believe that we were actually winning. It was still close when we got there. Then we saw on CNN that two counties were left, Hale and Dallas. People were biting their nails. But our group started celebrating, whooping it up. And an older white woman, wouldn’t you know, came over and told us to be quiet. She said, ‘No, hush, don’t celebrate, don’t jinx it!’ Well, we had literally just left Hale and Dallas counties. We said, ‘No, ma’am, we know what happened: We won.’ And of course, we did.”

What the lady didn’t know–what almost nobody realized—was how this seeming miracle, the biggest Democratic victory in Alabama since what felt like the Dawn of Time, had come about. The multiple allegations against Moore hadn’t tipped the election decisively in Jones’s favor; white Alabamians, including two-thirds of white women, had stuck with the Trump-endorsed Republican, who’d twice been booted from his job as state Supreme Court chief justice, most recently for defying federal law on same-sex marriage. But voters in predominantly black counties had shown up in numbers never before seen in non-presidential years. Black women—98 percent went for Jones—had made the ultimate difference.

The news was heartening but mystifying to Democrats outside the South, many of whom have long tended to view Alabama—like the rest of the South—as one big, unbroken expanse of incorrigible white racists, both a source and a symbol of everything ugly and backward about America. For decades, this stereotype dictated Democrats’ approach to the South. You couldn’t win statewide down there, the consultants said, without running white moderates adept at speaking the language of white conservatism.

To garner party support for a run in the South, Democrats distanced themselves from liberal ideas and black voters. Perhaps the most famous example of the latter was Bill Clinton’s “Sister Souljah moment” in 1992, in which he famously lambasted an “anti-white” rapper in an attempt to reinforce his appeal to conservative whites. This came not long after he’d made a show of returning to Arkansas to preside over the execution of a mentally disabled black man. Democrats could only win below the Mason-Dixon, the thinking went, by pandering to white “swing” voters.

There was only one hitch: Those “Reagan Democrats” became more staunchly Republican with every passing election. So as they hewed to the centrist Clinton strategy, Democratic losses accelerated during the 1990s and continued to mount throughout the Obama years, when a backlash to the country’s first black president wiped out Democrats at every level in the region. The party’s formula for winning Southern elections was becoming a recipe for failure. But instead of questioning the strategy, Democrats increasingly treated every loss in the region as fresh evidence that it was, and would always remain, a wasteland for any politics to the left of George W. Bush.

The South became the convenient place to blame and curse whenever Democrats lost the presidency or got creamed in the midterms. Liberals penned tomes like Whistling Past Dixie: How Democrats Can Win Without the South; they mass-shared post-election screeds like the anonymously written “Fuck the South,” which went viral soon after it was published in a Seattle weekly in 2004. (“Fuck ‘em,” the piece goes. “We should have let them go when they wanted to leave.”) In 2014, when conservative Democrat Mary Landrieu, aka The Senator from Big Oil, lost her re-election bid, Daily Beast columnist Michael Tomasky revived the argument liberal Yankees had been making for years: “Forget about the whole fetid place. Write it off. Let the GOP have it and run it and turn it into Free-Market Jesus Paradise. The Democrats don’t need it anyway.”

The South became the convenient place to blame and curse whenever Democrats lost the presidency or got creamed in the midterms.Setting aside the morals of leaving millions of blacks, Latinos, and poor whites to the tender mercies of the GOP, abandoning the largest region of the country—home to one-third of total electoral votes and climbing—was a specious strategy at best for winning national elections and electing majorities in Congress. It ignored Barack Obama’s victories in the three Southern states where he competed in 2008, and his two wins in the South in 2012. It devalued the votes of blacks, Latinos, and Asians, who together had overtaken whites in population in Texas, with Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi not far behind. Still, the irrational impulse to forsake the South did not subside after 2016, even after Donald Trump’s election made it perfectly clear that the appeal of white-supremacist politics was hardly limited to the states of the former Confederacy.

Black activists in the South certainly knew better. “There’s been historic underfunding and under-resourcing of Democratic structures in the South,” said DeJuana Thompson, a Birmingham native who, post-Trump, launched WokeVote, an ambitious effort to galvanize black millennials. “It’s not because black voters down here don’t care. Progressive groups and the Democrats found the time and money to engage folks in California, Ohio, New Hampshire, you name it—but they couldn’t find the same time to engage communities in Georgia or Mississippi or Alabama.”

Thompson, who ran Obama’s get-out-the-black-vote operations in North Carolina and Florida, knows from firsthand experience what paying attention to Southern voters can accomplish—and what the dearth of it, outside those two campaigns, has wrought. “There’s a void of political capital in these areas,” she said. “Then they turn around and say it’s because of non-interest on the part of black voters that these states aren’t voting the way they want. You write us off, then criticize us for not producing when we lose. You need to own the fact that you created the problem.”

In the aftermath of Trump’s victory, WokeVote, in conjunction with the Black Church PAC (another Thompson creation), Black Voters Matter, BlackPAC, and other burgeoning activist groups, along with local NAACP chapters, set out to do the work that Democrats had long neglected, or refused, to do down South. They began organizing year-round, not just in booming cities like Charlotte and Atlanta and Tampa, but in rural counties where nobody has asked non-whites to vote or participate in a long time, if ever. These efforts don’t revolve around particular candidates or elections; the goal was to “reimagine black voting power,” as Thompson put it, both registering new voters and inspiring and training others to run for local office. Brown of the Black Voters Matter Fund said, “The Democrats could never see our power, even if we did.”

The organizing efforts paid off faster than anyone could have predicted. Last year in Jackson, 34-year-old Antar Lumumba defeated an incumbent Democrat for mayor by promising to turn Mississippi’s capitol into “the most radical city on the planet,” quoting Karl Marx along the way: “As my comrade said, we have nothing to lose but our chains.” Up the road in Birmingham, another young and uncompromising black liberal, Randall Woodfin, upset another incumbent mayor with the help of Bernie Sanders and Our Revolution. In Virginia, where BlackPAC revved up communities of color, black progressive Justin Fairfax was elected lieutenant governor, while a notably diverse bunch of fellow lefties won seats in the House of Delegates, including the state’s first transgender and first two Latina representatives.

This year, a new wave of progressive candidates of color, along with white liberals like Texas’s Beto O’Rourke, has thrown out the old Republican Lite playbook altogether. Both at the top of the ticket and in hundreds of state and local races, Southern progressives are emphasizing identity politics and crafting lefty messages tailor-made to address the region’s long-standing ills, from racial and economic inequality and criminal injustice to abysmal health care and underfunded public schools. In states like Texas and Georgia, where Republicans assumed they’d win in a cakewalk in 2018 and beyond, the progressives are putting the GOP on the defensive and forcing the party and its dark-money affiliates to divert huge resources down South from other key races. If these new Southern Democrats succeed, they will do more than tear up the old assumptions about how to win in Dixie. Come November, the part of the country long blamed for strangling progressivism could nudge the national Democrats, along with the center of American political gravity, to the left.

The startling progressive victories in 2017 set the stage for a breakout midterm election season. In Georgia and Florida, two uncompromising black progressives, former state House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams and Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, won primaries over white centrists to become the Democratic nominees for governor. In Texas, O’Rourke has campaigned himself into a dead-heat against Senator Ted Cruz. In Mississippi, black former congressman Mike Espy (a more Obama-style progressive) has a real shot of winning his Senate race. The revolution is happening down-ballot, too: In Alabama, for instance, more than 70 black women filed for state and local offices. Across the region, young progressives have set their sights on seats in deep-red statehouse and congressional districts that have long offered no resistance to Republicans.

To some extent, Donald Trump is creating an all-boats-rise effect: Look no further than Tennessee, where the moderate former Democratic governor, Phil Bredesen, is surprising the experts by running strong in the race to replace Republican Bob Corker in the Senate. But it’s striking how little the new breed, exemplified by Abrams and Gillum, resembles the Democratic Party’s old stereotype of the ideal Southern candidate. Just four years ago, Democrats were running perfect models of the traditional formula for governor: Jason Carter, the grandson of Jimmy, lost big in Georgia by running as a “problem-solving, pro-business Democrat,” while in Florida, Democrats fielded an actual one-time Republican, former Governor Charlie Crist, who also came up short when non-white voters stayed home.

“When Republican voters have a choice between a real Republican and a fake one,” Gillum told me this summer, “they’re going to go for the real one every time. They’re not going to give their power away just because they like a Democratic nominee.”

Andrew Gillum, the liberal 39-year-old mayor of Tallahassee and a Democratic gubernatorial hopeful, speaks during a teachers rally in Miami Gardens, Fla., Aug. 19, 2018.Josh Ritchie/The New York Times/Redux

Andrew Gillum, the liberal 39-year-old mayor of Tallahassee and a Democratic gubernatorial hopeful, speaks during a teachers rally in Miami Gardens, Fla., Aug. 19, 2018.Josh Ritchie/The New York Times/ReduxDemocrats have long treated non-white voters as nothing more than afterthought. Democrats, Abrams told The Washington Post last year, “do not place the same premium on voters of color as we do on white voters. We’ve traditionally left them out of the politics, treated them as base voters, meaning they’ll show up if we have an election, and not as persuasion voters, who need to have the same degree of intensity and intentionality in our campaigning as we give to majority voters, to white voters.” Abrams said this was because Democrats’ image of the South had remained static. “People think I’m not gonna win because they’re still remembering the Georgia of Gone With the Wind, or maybe they’re conflating it with Selma. The reality is that the Georgia that people think they know is not the Georgia that is.”

Georgia today is a microcosm of the changes that have radically remade the South since the civil-rights revolution. Since the 1970s, when big banks and tech companies and foreign-based corporations started moving their headquarters to cities like Charlotte, Atlanta, and Houston, the region has basically been one massive construction site. Professional whites moved South for the new jobs. They were joined by blacks whose families had fled the Jim Crow South and who were now returning in a historic “remigration,” as well as by the nation’s largest influx of both Latino and Asian immigrants. The old insular South was changing fast.

As Republicans surged, Democrats let their state parties in the South fall apart and go broke; by the 2000s, for instance, the formerly dominant Mississippi Democratic Party could only afford one half-time staffer at state headquarters. Democratic national committees would (and still will) put money only behind centrist whites with establishment support down South, viewing progressives and candidates of color as sure losers if they weren’t running in gerrymandered districts. (You could send a black progressive like John Lewis, the civil-rights legend, to Congress again and again from his majority-black Atlanta district—but you’d never run the guy statewide.) As a result, Republicans got a free pass to take over everything—and to move politics and policy radically rightward in states that were simultaneously becoming more diverse.

Republicans got a free pass to take over everything—and to move politics and policy radically rightward in states that were simultaneously becoming more diverse.Particularly since the Republican landslide of 2010, though, the GOP majorities have pushed too far. Anti-LGBT legislation in states like North Carolina and Tennessee, punitive immigration policies in Georgia and Alabama, anti-abortion extremism in Mississippi and Texas, and the gutting of public schools throughout the region spurred grassroots rebellions like North Carolina’s Moral Mondays protests. The refusal of most Southern legislatures to accept Medicaid funding under Obamacare—an unpopular decision in almost all of these states—spawned more organizing and discontent.

The emerging generation of Southern Democrats has subscribed to the philosophy that Abrams started to lay down five years ago: Rather than trying to reconstruct the old majority-white Democratic coalitions that began to break up in the 1960s, the focus should be on building a fresh coalition that looked like the South of today. The New Georgia Voter Project, an ambitious voter-registration project Abrams founded in 2013, became one model for doing that. But after signing up voters, you have to inspire them—and Abrams also made it clear that, in her long-planned run for governor, she’d run on the kind of progressive platform that Democrats had long considered suicidal in states like Georgia.

Unlike Barack Obama or former Virginia Governor Doug Wilder (that state’s first black chief executive, in the 1980s and 1990s), Abrams has never downplayed the historic nature of her campaign to become the first black woman to run any state in America; like Gillum, she’s made it a selling point. “My being a black woman is not a deficit,” she said last year. “It is a strength. Because I could not be where I am had I not overcome so many other barriers. Which means you know I’m relentless, you know I’m persistent, and you know I’m smart.”

In May, Abrams steamrolled her white Democratic opponent in what had been touted as a close primary race, winning by a 53-point margin on the strength of record-setting turnout from the coalition she herself had helped to build. Her campaign got a big boost from WokeVote and Black Voters Matter, who had hightailed it to Georgia and expanded their efforts there as soon as Doug Jones’s victory was declared. “We are writing the next chapter of Georgia’s future,” Abrams declared in a powerful victory speech that brought back memories of Obama in Iowa in 2008. She hailed a new South in which “no one is unseen, no one is unheard, and no one is uninspired.”

Her emphatic win set up a marquee general-election showdown with Brian Kemp, the two-term, rifle-wielding Republican secretary of state who made his own national reputation as the voter-suppressing foe of Abrams’s New Georgia Voter Project—and gained further notoriety, along with Trump’s endorsement, by running one of the rawest race-baiting primary campaigns in memory, at one point airing an ad in which he promised to get in his truck to round up “illegals” and personally chase them out of Georgia. Despite the artificial advantage he’s given himself through eight years of disenfranchising minority voters and strictly enforcing one of the country’s most restrictive voter-ID laws, Kemp is deadlocked with Abrams in the general-election polls.

In neighboring Florida, Democrats had managed to lose five consecutive governor’s races by nominating milquetoast white centrists, even as the state voted twice for Obama. As the late-August primary approached, the polls showed that Florida Democrats were poised to dip into the same brackish well again by nominating Gwen Graham, a centrist white member of Congress whose father, Bob Graham, had been governor and then U.S. senator from the late 1970s to 2005. But two weeks before Election Day, when I spoke with Gillum—who’d been stuck in fourth place in the polls for a year, and long since written off by the pundits—he assured me that he was going to win. “The voters we need are going to turn out,” he said serenely.

LaTosha Brown, right, gets a hug from a well wisher before departing on The South Is Rising Tour 2018 on Aug. 22, 2018, in Stockbridge, Ga. John Bazemore/AP Photo

LaTosha Brown, right, gets a hug from a well wisher before departing on The South Is Rising Tour 2018 on Aug. 22, 2018, in Stockbridge, Ga. John Bazemore/AP Photo Gillum knew that he’d never come close to matching the spending of his four wealthy opponents (in a massive state where TV advertising is supposed to be the key to victory, he couldn’t afford to air a single spot until July). But he had the most extensive and innovative ground operation Florida Democrats had ever seen in a non-presidential primary. Out-of-state liberal benefactors Tom Steyer and George Soros had gone all-in behind him, funding GOTV efforts with paid organizers in vote-rich South and Central Florida. Bernie Sanders and Our Revolution jumped on the bandwagon late, but the Vermont senator’s rowdy final-week rallies with Gillum pumped up white progressives unaccustomed to having a candidate to get behind. WokeVote and Black Voters Matter were covering the ground up north, fanning out across the state’s “reddest” metro area of Jacksonville and firing up communities in the Panhandle, the so-called “Redneck Riviera” where black voters had long been ignored.

And as folks got wind of Gillum’s eye-opening platform—Medicare for All, a $15 minimum wage, marijuana legalization, gun control, and a $1 billion boost for public schools (who’d ever heard of such ideas in Florida?!)—they recognized that this wasn’t the same old Democratic song and dance. “Putting our flag in the ground and giving people something to vote for, and not just vote against—that’s how we win,” Gillum told me.

Lo and behold, he was right. On August 28—the day that Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech 55 years before, as Gillum frequently noted while stumping across the state—the son of a Miami bus driver defied the pollsters and consultants and won. And like Abrams, he drew a Republican opponent for the general election who’d offer the most vivid contrast possible.

Ron DeSantis, a right-wing congressman who rode Trump’s endorsement to an upset victory of his own, perfectly embodies the radical turn that Southern Republicans have taken. Right on cue, he kicked off the fall campaign by inserting his white-nationalist foot directly into his mouth. In a celebratory interview on Fox News, DeSantis started with code, calling his black opponent “charismatic” and “articulate” (he forgot to say “clean”). And then he let fly. Saying he wanted to “build off the success” Florida had experienced under Republican Governor Rick Scott, DeSantis said: “The last thing we need to do is monkey this up by trying to embrace a socialist agenda with huge tax increases.”

Yes, the man said “monkey.” And yes, the startled Fox host returned from a commercial break, decried his racist slur, and apologized for her guest. And then, as Gillum made his own rounds on cable TV, cooly noting that “Mr. DeSantis is taking a page directly from the campaign manual of Donald Trump,” the Republican nominee laid low for nearly a week—taking time, presumably, for nervous consultants to drill into him the do’s and don’ts of Republican race-baiting. Meanwhile, the polls show Gillum with a slight lead heading into November.

Many of the blunt-talking progressives running across the South this year—whether at the tops of tickets, or deep down the ballot in scores of school-board and city-council races—will inevitably fall short. A lot of these candidates are new to politics, often from humble backgrounds, bereft of the big-money connections that white Democrats long relied on. But what they lack in finances they’re making up for with savvy and state-of-the-art organizing.

“It doesn’t cost as much to play in a lot of Southern states, because of their size and their smaller media markets, so your dollar goes further,” DeJuana Thompson said. “And black women, Latino women, working-class women of all kinds—we know how to stretch a dollar.”

What Southern progressives lack in finances they’re making up for with savvy and state-of-the-art organizing.The progressive insurgencies down South bear a strong resemblance to those that have broken out up North in 2018. Like congressional candidates Rashida Tlaib in Michigan, Alexandria Cortez-Ocasio in New York, and Ayanna Pressley in Massachusetts, the insurgent Southern Democrats are running grassroots, door-to-door campaigns that eschew “likely voter” analytics and scripted consultant-speak—and they’re also winning without party backing, raising most of their money from small donors online. In one big respect, this is easier to pull off down South: Unlike in Detroit or Queens or Boston, there are no powerful and entrenched Democratic incumbents to overcome; there’s not much of a party organization to challenge, much less fend off. (If you want to run as a Democratic socialist in Louisiana on a budget of $30, go for it.)

But in another respect, Democrats face obstacles in the South that their Northern counterparts do not, including entrenched racism and voter suppression efforts. Which means that if their formula of unapologetic progressive politics and aggressive voter outreach pays real dividends, it could change the way Democrats across the country think about how to win elections.

For national Democrats in this crucial midterm year, the hidden benefits of a progressive surge down South are also starting to become clear: Republicans are having to redirect millions of dollars to defend key seats in Texas, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi, cutting into the resources they need to win elsewhere. And come Election Day, O’Rourke, Abrams, and Gillum—win or lose—will draw a lot of new Democratic voters to the polls. In Florida, Gillum could lose a close election even as his coalition puts U.S. Senator Bill Nelson, locked in a tight battle with Republican Governor Rick Scott, over the top in his re-election campaign, along with a host of candidates down ballot as well.

The same goes for local races where Republicans are being caught unawares by progressive insurgents like Sanjay Patel, the Sanders-endorsed Indian-American who’s mounting the first serious challenge ever to Congressional Freedom Caucus member Bill Posey, a four-term Republican, on Florida’s Space Coast. “The Republicans here don’t know what to think,” Patel told me recently. “They keep asking, ‘Where’s all your money coming from?’ As if we’re spending millions. I wish.”

The future of Southern politics is, both metaphorically and literally, cruising down the backroads of the Deep South, in a big black bus with images of fist-clenching black folk painted on the sides beneath the big bold slogan of Black Voters Matter: “The South Is Rising.”

LaTosha Brown and Cliff Albright leased the bus in August. When we talked by phone on a recent Saturday, they had just pulled out of Memphis, where they’d spread the message at a parade—“handing out candy and saying radical things,” Albright joked—and met with dozens of local grassroots activists who could hardly believe what they’d been seeing in Florida and Georgia and Alabama. “We needed a big bang when we pull into these communities,” Brown said. “So many folks feel isolated, especially in the rural South—black folk, Latinos, white progressives as well. We want them to know: You are not alone, you are not isolated, you are loved.”

As Brown and Albright hoped, the bus, with its evocations of the civil rights–era Freedom Rides, has also caught the eye of the national media, including The Associated Press and The New York Times. “We’re blowing some minds,” Brown said, chuckling. (There is a lot of laughter on this bus, along with a fair amount of singing.)

The journey began, for the organizers, in a less glamorous fashion. Like VoteVote, Black Voters Matter was born from years and years of small victories and great struggles—and from a sharp Southerner’s eye for the opportunities, after Trump’s election and the Democratic disaster of 2016, that an increasingly myopic Democratic Party could not have discerned. “We didn’t wait for anybody to give us permission,” Brown says. “We did not wait to move till we got a million-dollar grant.”

“Though we’d take one!” Albright chimed in.

“We moved before we ever got a dime,” Brown continued. “We believed we’d have everything we’d need. Because we know these people. We are these people! And the ones we didn’t know, we were willing to meet where they are,” Brown said.

She added, “A diamond is coal under extreme pressure. There are diamonds in the South. We are using our resilience to shift this thing. Not just here. We will change this country. Watch and see.”

From the moment President Donald Trump tapped Brett Kavanaugh to replace Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court in early July, until the first allegations of sexual assault surfaced against the nominee in mid-September, the most pressing question was whether the would-be justice represented the deciding vote in the decades-long effort to overturn Roe v. Wade. To some on the left, the answer was apparent.

If Brett Kavanaugh becomes a Supreme Court justice, will he help gut or overturn Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion in America? Yes, of course he will.

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) September 5, 2018Now the American people know what we know. We have every reason to believe Kavanaugh will overturn Roe v. Wade. https://t.co/P4vEFdIezk

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) September 6, 2018While Kavanaugh, who was sworn in on Monday, will likely play an influential role in shaping the future of abortion rights in America, even some of Kavanaugh’s fiercest Democratic opponents in the Senate understood that the heavy lifting of scaling it back is the work of state legislatures and the lower federal courts. “It matters if they overturn Roe v. Wade, which I doubt they’re gonna do,” Senator Mazie Hirono told ABC’s This Week. But, she rightly added, “the states are very busy passing all kinds of laws that would limit a woman’s right to choose. It’s those things that will go before Justice Kavanaugh.”

That work is already under way.

In September, two federal appeals courts handed down rulings in favor of laws curtailing access to abortion. In the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, a three-judge panel upheld a Louisiana law that requires doctors who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. An Eighth Circuit panel declined a local Planned Parenthood clinic’s request to block a similar measure in Missouri. Additionally, the full Sixth Circuit is weighing an Ohio law that blocks federal funds for some public-health programs from going to abortion providers.

In the Fifth and Eighth Circuit cases, both courts adopted a narrow interpretation of the Supreme Court’s 2016 ruling in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. That 5-3 decision—the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat had yet to be filled—struck down a 2013 Texas law that required clinics that provide abortions, and the physicians who perform them, to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles. The law would have closed all but a handful of the state’s 40 abortion clinics at the time. In some parts of Texas, tens of thousands of women who sought the procedure would have had to travel more than 100 miles in each direction to obtain it.

The Fifth Circuit had upheld those restrictions as a valid exercise of Texas’s regulatory powers. But the Supreme Court said the lower court did not properly weigh women’s interests in that equation. “We conclude that neither of these provisions confers medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes,” Justice Stephen Breyer wrote for the majority. “Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a pre-viability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access, and each violates the Federal Constitution.”

These burdens were no accident, of course. Admitting-privileges laws are often designed to force physicians who provide abortions to close down their practices, and to effectively prevent pregnant women who don’t have the means to travel long distances from getting an abortion. Anti-abortion groups often defend the laws as necessary to protect women’s health, but since serious complications from abortion are rare, multiple federal courts have found that the laws have a minimal effect in furthering that goal. Some federal judges have concluded that admitting-privileges laws may actually have the opposite effect, making it harder for women to safely obtain the procedure.

After Hellerstedt, a Planned Parenthood clinic in Missouri challenged that state’s 2007 law and the regulations that implemented it, which imposed similar admitting-privileges requirements. A federal district-court judge agreed to issue a preliminary injunction against enforcing the law, citing Hellerstedt to justify its decision. The Eighth Circuit quashed the preliminary injunction last month and concluded that the Supreme Court’s ruling may not carry much weight beyond the circumstances in which it was decided.

“Hellerstedt did not find, as a matter of law, that abortion was inherently safe or that provisions similar to the laws it considered would never be constitutional,” Judge Bobby Shepherd wrote for the unanimous panel. “Despite the district court’s assertions to the contrary, Hellerstedt’s analysis of the purported benefits of the law at issue were, of course, related to what the law in that case regulated: abortion in Texas.” As a result, one of the two clinics left in Missouri that still performs abortions announced it would no longer offer the procedure.

After the Hellerstedt ruling, a federal district-court judge ruled that Louisiana’s own admitting-privileges law—Act 620, which passed in 2014—would unconstitutionally hinder women’s access to the procedure if implemented. The court found that four of the five doctors had made a good-faith effort to obtain privileges, but failed to obtain them. As a result, only one clinic would remain open in Louisiana if Act 620 went into effect. Since that clinic’s sole doctor could only perform a finite number of procedures each year, the court estimated that 70 percent of women in the state would be effectively unable to obtain an abortion. “In short, Act 620 would do little or nothing for women’s health, but rather would create impediments to abortion, with especially high barriers set before poor, rural, and disadvantaged women,” the court concluded.

Once again, the Fifth Circuit disagreed. In its decision last month, a three-judge panel concluded in a 2-1 decision that Act 620 didn’t impose an undue burden on Louisiana women’s access to abortion. The ruling is an impressive feat of judicial sleight of hand. Hellerstedt was a clear repudiation of the broad latitude that the Fifth Circuit had offered Texas when it tried to regulate abortion into near-oblivion, but the panel recast the Supreme Court’s ruling as a narrow, fact-bound decision so that it could take a similarly broad approach. It disputed the lower court’s findings, concluding that only one of the physicians had made a good-faith effort to secure admitting privileges. As a result, only 30 percent of Louisiana women would be affected, which amounts to more than 700,000 people. Moreover, the doctors had “failed to establish a causal connection between the regulation and its burden―namely, [their] inability to obtain admitting privileges,” Judge Jerry Smith wrote for the majority.

Judge Patrick Higginbotham, writing in dissent, disputed his colleagues’ factual assessments. He also highlighted the absurdity of their approach to the act’s burdens on women. “The majority today essentially holds that, because private actors (the physicians) have not tried hard enough to mitigate the effects of the act (a conclusion contradicted by the district court’s factual findings), those effects are not fairly attributable to the act,” he wrote. “That position finds no support in [Hellerstedt].”

Most importantly, he concluded that the panel had stretched the Supreme Court’s “undue burden” test for abortion regulations beyond recognition. “At the outset, I fail to see how a statute with no medical benefit that is likely to restrict access to abortion can be considered anything but ‘undue,’” Higginbotham wrote. “As I have explained, the majority draws conclusions for which there is no support in the record and rejects the district court’s well-supported findings.” It’s possible that the Fifth Circuit’s decision could reach the Supreme Court, giving Kavanaugh his first chance to weigh in on abortion from the high court.

Both rulings underscore the perilous legal footing on which abortion rights now rest. Roe v. Wade’s last brush with mortal peril came in 1992, when the justices heard Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Four of the court’s conservative members had already indicated in previous cases that they would overturn the 1973 decision if given the opportunity. They did not get the chance to do so. Instead, justices Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter sided with the court’s liberals to reaffirm that the Constitution protects a woman’s right to obtain an abortion and to establish the “undue burden” test to weigh regulations of it.

Supporters of abortion rights were relieved, but knew the fight wasn’t over. “I fear for the darkness as four justices anxiously await the single vote necessary to extinguish the light,” Justice Harry Blackmun, Roe’s original author, wrote in his concurring opinion in Casey. I noted earlier this year that Blackmun’s prophesied darkness had finally arrived in the form of Brett Kavanaugh. Leading organizations that oppose and support abortion rights both expect Kavanaugh to be more deferential to state and federal restrictions on abortion. That could bode well for Republican legislatures that want to regulate abortion out of existence—and it goes without saying how it bodes for women’s right to obtain one in those states.

Razer is adding two new members to the Razer Blade 15 family in the forms of a a new base model that starts at $1,599 and a Mercury White Limited Edition, starting at $2,199.

Razer is adding two new members to the Razer Blade 15 family in the forms of a a new base model that starts at $1,599 and a Mercury White Limited Edition, starting at $2,199. The Alienware m15 is just 0.8 inches thick with up to a Nvidia GeForce GTX 1070 Max-Q.

The Alienware m15 is just 0.8 inches thick with up to a Nvidia GeForce GTX 1070 Max-Q.

No comments :

Post a Comment