Graham Greene famously observed that there is a splinter of ice in the heart of every writer, and certainly this is true of that generation of middle-class male novelists born in the decade before 1914. These were the men who, as one of them, John Heygate, remarked, were “too young to enter the war, too old to inherit the peace.” What they had in common was a deep-seated strain of melancholy verging on, and frequently lapsing into, a curiously unemphatic, almost whimsical form of despair. Heygate, a minor novelist and man-about-other people’s wives, killed himself in the 1970s, leaving instructions for his friends to have a lavish, celebratory meal after his funeral. Their outlook upon the world may have been bleak, but they did have style, those chaps.

Anthony Powell, the subject of Hilary Spurling’s elegant, affectionate biography Dancing to the Music of Time, was afflicted by recurring and utterly debilitating bouts of depression, one of the worst of which followed the discovery, after the event, of his wife’s adultery sometime in the 1940s. Nicholas Jenkins, the affectless narrator of Powell’s most famous work, the multivolume novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, published between 1951 and 1975, shares many of his creator’s own traits. He springs to something most closely resembling life on those occasions when he recalls an early love who betrayed him, and the torments of jealousy that he, like Powell, suffered because of her unfaithfulness: “I felt as if someone had suddenly kicked my legs from under me, so that I had landed on the other side of the room…with all the breath knocked out of me.” This is spoken, we feel, in a tone very close to Powell’s own.

ANTHONY POWELL: DANCING TO THE MUSIC OF TIME by Hilary SpurlingKnopf, 480 pp., $35.00

ANTHONY POWELL: DANCING TO THE MUSIC OF TIME by Hilary SpurlingKnopf, 480 pp., $35.00A Dance, as internal evidence suggests, and as Spurling frequently confirms, is Powell’s largely autobiographical account of the period just before what used to be called the Great War, through World War II, and into the 1970s. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it is a fictionalized group portrait of certain people living in those times, since Jenkins, the narrator, figures as a version of Woody Allen’s character Zelig. He is a mostly passive participant in all the major events of the elaborately detailed plot, as he encounters dodgy aristocrats, artists manqués—in Jenkins’s world no one is ever quite first rate, and quite a few are hapless failures— aspiring politicians and expiring relatives, femmes fatales, money men and wastrels, peace-loving soldiers and warlike civilians: a latter-day Vanity Fair, in other words. Towering over all, in all his egregious awfulness, is the horribly memorable Kenneth Widmerpool, whose self-promoting machinations are among the forces that drive the novel sequence.

Powell himself, according to his biographer, considered the central theme of the sequence to be “human beings behaving.” Although it is hard to think what characters, like real people, might do other than “behave,” the most appealing quality of A Dance is the almost hallucinatory sense it conveys of real people performing real actions in a wholly realistic world. Powell had, as Spurling has him say of Shakespeare, “an extraordinary grasp of what other people were like.” As a novelist, he had an unusual ability to portray large gatherings of people, and he made the phenomenon of “the party” one of his specialties. His women are particularly convincing, while his best male characters are the louche and slightly disreputable ones. He is not as acute as Evelyn Waugh, the writer to whom he is most often compared, and is certainly not his equal as a stylist, but Powell is a far more disinterested writer than Waugh, and lets his characters reveal themselves in a wholly natural way that Waugh would not have been capable of. Waugh’s fiction always bears the artist’s stamp, whereas Powell’s work appears self-generated.

As an avid observer of the comédie humaine, Powell was drawn to John Aubrey, the seventeenth-century author of Brief Lives, a series of short, often comic, and sometimes scurrilous biographical sketches of numerous of the author’s contemporaries. “He contemplated the life round him as in a mirror,” Powell admiringly wrote in his biography of Aubrey,

He was there to watch and to record, and the present must become the past, even though only the immediate past, before it could wholly command his attention. For him the world of action represented unreality.

Powell, in his novels, took a similar stance in regard to his characters and the time they lived in. He catches perfectly the curiously languid pace of twentieth-century middle-class English life, which persisted even through two world wars, and which self-deluding Brexiteers vainly imagine can be reinstituted in today’s globalized world.

Powell’s own life spanned most of the last century—he was born in 1905 and died in 2000—and despite his urge toward self-effacement, it was in its way every bit as active, noteworthy, and odd as the lives that John Aubrey sketched, or as the fictional lives of the multitude of characters Powell himself invented over the span of his career. He was born in “one of 159 identical furnished flats in a set of five monolithic blocks” near Victoria Station in London. His mother’s people had been landed gentry in a small way, but they lost their modest fortune in the costly and vain pursuit of a peerage. Powell’s paternal grandfather, Lionel, settled near Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire and became a surgeon of sorts in order to finance his passion for foxhunting. He “relied throughout his career on the hunting shires around Melton,” Spurling writes, “for a steady supply of fresh fractures” to treat.

Philip Powell, Lionel’s son and Anthony Powell’s father, as a boy had been “blooded” by being smeared with the tail of a newly killed fox, an experience that, Spurling says, “seems to have inoculated him against the sport of kings ever after.” Still, he cannot have been entirely averse to bloodshed, since he became a career soldier. He was a “dashing young subaltern” of not quite 18 when he fell in love with his future wife, Maud, an impossibly young-looking 33-year-old, whose “banjo solos were a star attraction of the Ladies Mandoline and Guitar Band” in the 1890s. She had known Philip since he was a baby. The couple had to wait three years for Philip to reach 21 so that they could marry without the consent of his parents. The marriage was happy enough at first, but Maud soon became depressed by the conviction that she was looked upon as a cradle-snatcher. She shunned society and even her own friends and settled into a reclusive life, which, luckily, suited her husband—and which Nick Jenkins describes with subdued pathos as the lives of his own parents in The Kindly Ones, the sixth volume of A Dance.

These facts of his early life no doubt contributed to Powell’s lifelong diffidence and cool detachment from the lives going on around him, lives that he nevertheless tracked with the obsessiveness and detailed attention of a Nabokovian naturalist. Growing up “in rented lodgings or hotel rooms,” he was “constantly on the move as a boy,” and, Spurling proposes, he “needed an energetic imagination to people a sadly underpopulated world from a child’s point of view.” And these years perhaps shaped his view of himself as a keen-eyed outsider. A slight figure, with notably short legs, he used to represent himself in marginalia in his letters as a dwarf, complete with bobbled hat and bootees.

Powell’s father seems genuinely to have loved his wife, and probably loved his only child, too, but as the years went on he became a sort of second son to Maud, who it sometimes seemed “had to deal with two implacable infant male egos.” Indeed, accounts of Philip Powell’s character and behavior give a new and forceful meaning to the word irascible. In old age, when he was living in solitude in a seedy London hotel, the management, unable any longer to tolerate his impossible behavior, issued an ultimatum for his removal to a nursing home. Anthony’s wife, Violet, traveled up from their home in the country to break the news to the old boy, who, Spurling writes, “pre-empted alternative plans for his future by dying the same day.” At the funeral, Powell heard an explosion from a nearby quarry that sounded to him, so he told his son Tristram, “like Grandfather being received in the next world.”

Like many of the sons of English middle-class parents of the time, the boy Anthony—or “Tony,” as Hilary Spurling, who was a friend, calls him throughout her book—was dreadfully unhappy at school. He went first to the New Beacon School at Sevenoaks in Kent, where most of the pupils came from military families. He was lucky in making a close friend there, Henry Yorke—later to be the novelist Henry Green, another product of that melancholic prewar generation—who later described being offered “a stinking ham oozing clear smelly liquid, and boys so hungry they ate raw turnips and mangel wurzels” stolen from the farmers’ fields roundabout. For years after he left the school, Powell had recurring nightmares of being back there, until in his late 20s he dreamed he had killed the headmaster, which proved a curative.

He had recurring nightmares of being back at school, until in his late 20s he dreamed he had killed the headmaster, which proved a curative.

From the Beacon, Powell went on to Eton, which seems to have been, if only by comparison, an improvement on what had gone before. Some of the housemasters there were interesting, and at least one of them, Arthur Goodhart, would find his way into A Dance as the restless, dim, and faintly sinister Le Bas, who is a mass of physical tics, has numerous passages of second-rate verse off by heart, and on one occasion is caused to be arrested by the police, a prank played on him by Charles Stringham, Jenkins’s friend and one of the most vivid characters in the sequence. It was at Eton that Powell developed his interest in and talent for drawing, and from the beginning, according to Spurling, he “found his own natural habitat in the Drawing Schools on Keats Lane.” However, although his imagination was in many respects pictorial, he did not have the makings of an artist in this medium, and his drawing remained confined to caricatures and amusing sketches.

Throughout his life, though, he kept up the habit of assembling scrapbooks and murals, some of them considerable in size, style, and prolixity, from images cut out of newspapers and magazines—examples of these adorn the endpapers of Spurling’s biography—which might be speeded-up, manic versions of Poussin’s masterpiece A Dance to the Music of Time. The painting, which hangs in The Wallace Collection in London, and to which Powell returned again and again, shows a quartet of figures, three women and a man, engaged in a round dance to the music of a lyre played by the figure of Time, an elderly, naked man. Recalling in his memoirs his first view of the painting, he wrote, “I knew all at once that Poussin had expressed at least one important aspect of what the novel must be.”

One guesses this aspect to be what he referred to, with the urgency of italics, as “the importance of structure.” What Powell took from Poussin is a classically balanced coolness of style and treatment. Because one reads A Dance close-up, necessarily—it is after all a compelling, even a rollicking, narrative, except perhaps in the wartime sections, where, paradoxically, the pace slackens to a slow march—it is easy not to notice how tightly and expertly woven the tapestry is. Despite the claims of some of his more excitable admirers, Powell is a much lesser artist than Joyce, lacking Joyce’s stylistic exuberance and his determination to break out of the bonds of the traditional novel form. Yet he could with justice claim of A Dance, as Joyce did of Ulysses, that it is a triumphant feat of engineering.

Somewhat surprisingly, and unlike his friend and friendly rival Evelyn Waugh, Powell detested Oxford and chafed throughout his time at the college. Probably he was too solitary a soul—and too confirmed a heterosexual—to relish the jostling, sybaritic pleasures on offer in the City of Dreaming Spires in the interwar years. One night at dinner he made the mistake of confessing his distaste for college life to the legendary don Maurice Bowra, who was so shocked at the notion of anyone not venerating the alma mater that a rift was opened between the two men that was to last for 35 years. Spurling has no doubts that Powell’s happiest, or least unhappy, time at Oxford was his last year, when he was sharing rooms with Henry Green and they were discovering together, among other glories, Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, as each new volume appeared. Proust was, along with Poussin, a vital discovery of Powell’s younger years, the great exemplar who showed him what wonders, not only of narrative but also of style and form, could be achieved in the roman-fleuve.

Powell got out of Oxford as quickly as he could and went to work for the venerable and highly dysfunctional publishing firm of Gerald Duckworth & Co. Spurling’s pages on this period of his life, like the fictional version of it in A Dance, contain some of the most richly entertaining passages in the biography. Gerald Duckworth was a figure that Powell, or Waugh, would hardly have dared to invent. He “smoked foul-smelling cigars, enjoyed a bottle of claret a day over lunch at the Garrick, and was often half-tipsy in the office.” More pertinently, he hated books and, according to the head of a rival publishing house, he considered authors “a natural enemy against whom the publisher must hold himself arrayed for battle.”

In looks, Powell was no matinee idol, and to many he seemed cold, aloof, and arrogant, yet a remarkable number of remarkable women fell in love with him, or at least suffered him to fall in love with them. Few of his early affairs were satisfactory, until he met Violet Pakenham in the summer of 1934. The encounter took place at Pakenham Hall in County Westmeath, Ireland, seat of the Earl of Longford, who had inherited the title at 13 and later repudiated it, being an Irish nationalist to the extent of changing his name to Eamon de Longphort. The family was a sort of Irish version of the Mitford clan, though possibly a shade more eccentric, if such seems possible.

As the dance of life proceeded around him, by turns gay and melancholy, Powell watched, he listened, he noted.

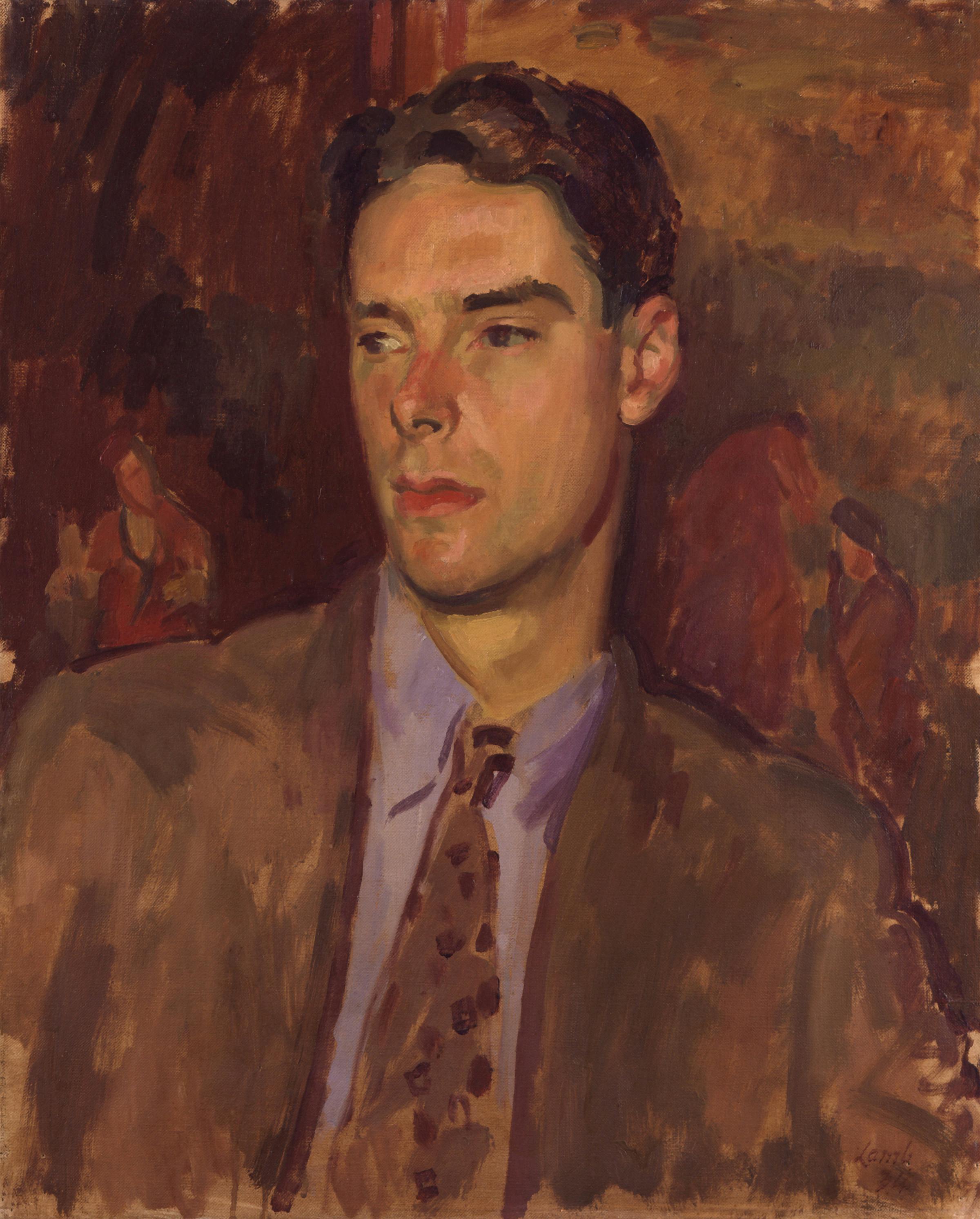

Powell was attending a house party at the Hall, not very happily; Christine Longford was also a novelist, and jealous, like all novelists, so that from the start the occasion was touched with a definite froideur. Powell was having his portrait painted by Henry Lamb, Edward Longford’s brother-in-law, who summoned his wife’s sister to keep the model from fidgeting. This indicates a touching naivety of the painter’s part, since Violet Pakenham was beautiful, intelligent, and a definite “catch”—Marion Coates, a girlfriend of Powell’s at the time, remarked wryly years later that she could quite see why he would throw her over in favor of the daughter of a belted earl.

After the sitting, Violet took Anthony outside to the kitchen garden and, in an Edenic gesture, conscious or otherwise, picked him an apple; that evening, as Violet wrote years later, there began “a conversation which has continued unabated until this day.” The marriage was long and happy, surviving even Violet’s secret affair with the man—Spurling has been unable to identify him—whom she described to Sonia Orwell as “the love of her life.” When Powell found out about Violet’s betrayal—probably in 1946, according to Spurling—“he plunged into a hole of depression, exhaustion and almost insane overwork.”

Powell was indeed a prodigious worker, who in his early years as a writer could read and review five or six books a week. Over his lifetime, he produced 19 novels, five volumes of memoirs and three of journals, a writer’s notebook, and, for good measure, two plays. As an artist, he probably lived too long: His work was largely done by the mid-1970s, when he published Hearing Secret Harmonies, the final volume in the Dance series, and when the world in which the series was set had largely disappeared. He spent the remainder of his life doing little more than tidying his desk, as Spurling tacitly acknowledges by wrapping up those years in an appositely titled, and decidedly perfunctory, 13-page Postscript.

Although all of Powell’s novels sparkle, if not all the time, his true achievement is A Dance. Even though it is probably not quite as good as many, including Powell himself, considered it to be, it will live if only through a handful of characters who have become emblematic of a milieu and a time. These include the toadlike Widmerpool; Charles Stringham, funny, fey, and doomed; Pamela Flitton, shamelessly based on the beautiful man-eater Barbara Skelton—who threatened to sue, but settled instead for advice on getting a novel published; the crafty, avaricious, and unforgettably awful Uncle Giles; and Jenkins’s lost love, the beautiful betrayer Jean Duport. These are, as Evelyn Waugh said of Captain Grimes in Decline and Fall, among the immortals.

And it was Waugh who paid Powell the best and certainly the most elegant tribute one novelist could bestow upon another. In an uncharacteristically warm and generous assessment of his friend’s masterwork, he wrote:

Less original novelists tenaciously follow their protagonists. In the Music of Time we watch through the glass of a tank; one after another various specimens swim towards us; we see them clearly, then with a barely perceptible flick of fin or tail, they are off into the murk. That is how our encounters occur in real life. Friends and acquaintances approach or recede year by year…Their presence has no particular significance. It is recorded as part of the permeating and inebriating atmosphere of the haphazard which is the essence of Mr. Powell’s art.

Despite inevitable flaws and weaknesses, Anthony Powell was a master of the traditional English novel form. As the dance of life proceeded around him, by turns gay and melancholy, he watched, he listened, he noted, with the most careful interest and attention. “Try,” Henry James, in his great essay The Art of Fiction, urged the tyro novelist, “to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.” Anthony Powell was without doubt an artist of that rare kind.

In the summer of 2017, when the midterm elections were more than a year away but already on everyone’s mind, Democrats seemed to have an embarrassment of riches.

President Donald Trump was historically unpopular and engulfed in myriad scandals, from the tawdry (an alleged affair with a porn star, covered up with campaign funds) to the corrupt (using the presidency to enrich family businesses) to the existential (Robert Mueller’s investigation into the Trump campaign’s possible collusion with the Russian government to influence the 2016 election). Some of Trump’s cabinet members were similarly engulfed. His White House had become a reality TV psychodrama that not even Bravo’s producers could have dreamed up. And Congress, despite Republicans’ unified control of the government, was failing to accomplish much at all—including its years-long promise to repeal Obamacare.

Presented with so many gifts, Democrats’ only question was whether they should focus on one issue or try to synthesize them all into a single, winning message. “That message is being worked on,” Congressman Joseph Crowley, the number-four Democrat in the House, told the Associated Press. “We’re doing everything we can to simplify it, but at the same time provide the meat behind it as well. So that’s coming together now.”

It did not come together—not then, not ever. The midterms are less than three weeks away. The Democratic Party still hasn’t found its message, and the issues that many thought would feature prominently on the campaign trail—impeachment, Russia, corruption, #MeToo—have largely been relegated to subtext. But somewhere along the way, Democratic candidates around the country, almost in spite of the party’s dithering, have found the winning message themselves.

A year ago, if you were watching cable news—and not following the candidates—the major issues of the campaign would have seemed apparent.

The Russia inquiry had ensnared some of Trump’s top campaign and cabinet officials, including his former chairman, Paul Manafort, and national security adviser, Michael Flynn—both of whom are now convicted felons. And Trump’s firing of FBI Director James Comey suggested a possible attempt at obstructing the Russia investigation.

The president’s corruption, which he only barely seemed to hide, was underscored by the signing of a massive $1.5 trillion tax cut that will greatly benefit him and his family businesses. Trump’s administration, meanwhile, has been marked by ethics scandals and taxpayer waste. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price resigned after it was revealed he had spent more than $1 million on private flights, while EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt left the administration after spending hundreds of thousands on first-class travel.

Trump’s record on women—his well-documented history of misogyny, and the many allegations of sexual misconduct against him—was also believed to be a potent election issue, especially since it seemed to be driving the unprecedented number of Democratic women running for office. Kavanaugh’s confirmation battle, which was fractious even before the emergence of allegations of sexual assault, only underlined the GOP’s vulnerability with women.

The number and breadth of these scandals created perhaps the biggest debate in Democratic circles over the past year: whether the party should pin its 2018 hopes on promising to impeach Trump. A few House Democrats support the idea, but party leaders have danced around the question—a recognition, perhaps, that the issue could hurt the party in November. While a significant majority of the party’s base (and megadonor Tom Steyer) support impeachment proceedings, polls consistently show that fewer than half of all Americans do.

Though cool on impeachment, the Democratic Party has repeatedly grasped for a similarly compelling, unified message. Its first attempt, unveiled in July 2017, was the well-conceived, poorly received “A Better Deal,” which stated that the party’s mission was “to help build an America in which working people know that somebody has their back. American families deserve A Better Deal so our country works for everyone again, not just the elites and special interests.” The message went nowhere. Almost exactly a year later, the party rolled out the even more milquetoast “For the people.” Most Democratic lawmakers, if put on the spot today, likely could not explain the three main issues the message represents.

This has led to some familiar Democratic anxiety. Writing in The Atlantic in August, former Democratic Congressman Steve Israel described attending a campaign fundraiser in “a plush residence on the 64th floor of Trump World Tower,” where “most in the crowd wanted to know one thing: What’s the Democratic message?”

“There, in a building staffed with uniformed doormen, standing on floors so fine that we’d been asked to remove our shoes, the donors demanded to know why their party had no unifying theme. Or, more precisely, why wasn’t the message the specific message that they wanted messaged?” he continued. “These questions have come up at Democratic gatherings across the country this year, from grassroots fund-raisers to posh weekend retreats.”

Israel argued that “Democrats have it wrong that they need a national-message template in the first place. Past elections have shown that the most effective messaging is local and specific to each district.” This year’s election seems to be proving this true, or at least Democratic candidates are campaigning as if it is. By and large, they are running on a single issue. It’s not impeachment or collusion or corruption or #MeToo; it’s not even specific to Trump. The election, for many Democrats, is all about health care.

“The top three issues this year are health care, health care, health care,” J.B. Poersch, the head of the Democratic Senate Majority PAC told CNN last week. Candidates across the country, from Cindy Axne in Iowa to Claire McCaskill in Missouri to Josh Harder in California are talking about their own struggles dealing with the high cost of medical care. West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, toe lone Democratic senator to vote to confirm Kavanaugh, is leading in the polls in his state, thanks in large part to his embrace of Obamacare, which he even made an issue during the most recent Supreme Court confirmation.

Republicans are following suit, even those who voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017. Republican Martha McSally, who is running to fill Jeff Flake’s Arizona Senate seat, has campaigned on protecting coverage for pre-existing conditions, despite voting for the AHCA, which would have repealed the ACA, last year. In a debate on Monday, she told voters, “We can’t go back to where we were before Obamacare.”

Trump’s most significant legislative accomplishment, the $1.5 trillion corporate tax cut passed last December, has also factored into Democratic messaging—partly to highlight the hypocrisy of Republicans’ deficit hysteria during the Obama years, but also as another way to discuss health care.

Journalists and politicians talk about “the health care repeal and the Trump tax plan as two different issues,” Democratic consultant Jesse Ferguson told CNN back in May. But “the voters see them as ways Washington isn’t looking out for them.... On both of them, it’s basically the same: [Republicans] have been giving tax breaks to health insurance companies, to pharmaceutical companies, and those come at the expense of people who work for a living. It means higher health care costs, eventually higher taxes, more debt for your kids, and cuts to Social Security and Medicare as you get older.”

After Mitch McConnell said on Tuesday that entitlement cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security are the only way to reduce the deficit, Democrats immediately sent out emails tying his statement to the tax cut.

Heads up for the "Dems have no national message" people: The McConnell comments on entitlements are driving today's state Dem messaging. pic.twitter.com/OzCvauPMax

— Dave Weigel (@daveweigel) October 16, 2018It’s possible, of course, that Democrats are focusing on these issues in part because they don’t have to draw more attention to the president’s scandals, which already dominate cable news. The party’s fear has long been that its message, whatever it may be on a given day, would be drowned out by all things Trump. But the wall-to-wall coverage of Trump may in fact be helping Democrats. His scandals are now inevitably woven into the fabric of the 2018 campaign, such that Democratic candidates don’t need to go hoarse talking about Mueller or Trump’s tax returns or Stormy Daniels; voters are already motivated one way or another by those matters. Instead, Democrats can spend their time hammering the single issue that Republicans are most vulnerable on—which also happens to be the issue that voters care the most about.

“There isn’t even a one in a million chance that Merkel will say no.” These were the words of Alexis Tsipras shortly before becoming Greece’s prime minister in 2015. He was talking about his alternative negotiation proposals for Greece’s European Union bailout agreement—clearly in the EU’s interests, from his perspective, and vastly more palatable for Greece.

Populist politicians excel at presenting an effortless route to a rosy future. In the run-up to the UK’s referendum vote in 2016, Boris Johnson—then London mayor, now ex-foreign minister, and perennial prime ministerial hopeful—expressed his certainty that, after Brexit, the EU would surely agree to a tariff-free trading deal, just like the one the UK enjoyed by being in the EU: “Do you seriously suppose that they are going to be so insane as to allow tariffs to be imposed between Britain and Germany?” Both Tsipras and Johnson saw the future negotiation results as a done deal, bound by the EU’s own economic interests. All the people had to do was vote the right way.

Greece found out the hard way that simply voting for the future deal you want isn’t enough when negotiating with a transnational institution representing 27 other democracies. It also found out that Tsipras and his government had been too arrogant in claiming to know what was in the EU’s interests. Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, was not so taken by Tsipras’s alternative proposals, and insisted instead on the “austerity and reforms” recipe that Greece had been following.

Meanwhile at the EU summit on Wednesday, more than two years after the country voted for Brexit, and with less than six months until the UK’s deadline for leaving the EU, the UK is still negotiating its withdrawal agreement and the terms of the future EU-UK relationship. The UK’s Brexit vote resembles that of Greece’s vote for Tsipras not only in terms of the political naiveté of the populist promises, but also in terms of the strategies pursued in the subsequent negotiations with the EU. Both the Conservative government and the Labour opposition in the UK seem to be repeating Greece’s mistakes. The result is unlikely to be any more successful.

Prime Minister Theresa May is wedded to the withdrawal proposal her government arrived at after much deliberation: the so-called Chequers plan. May sees this as the best compromise possible, given the internal politics of her own government. Pro-EU members of parliament (MPs) want as close a relationship with the EU as possible, whereas pro-Brexit MPs want a relationship that gives the UK as much autonomy as possible. As a result, the Chequers plan is a patchwork that has been described by two confectionary analogies: “having your cake and eating it” and “cherry-picking.” It involves enjoying some of the benefits of EU membership, such as the free movement of goods, but without many of the commitments that come with it, such as the free movement of people.

The problem with Chequers is that the EU has signalled many times, including in a mocking Instagram post by EU president Donald Tusk, that the EU will not accept it. This has led to a stand-off. After the Salzburg summit last month, when the Chequers’ plan was once again rejected by the EU, May restated that Chequers was the only credible proposal the UK was prepared to make, and that the EU should offer an alternative, if it cannot accept it. Of course, the EU has offered the UK the alternatives: membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), or a Canada-style trade deal. May in turn finds those proposals unacceptable. Staying in the EEA would involve the continued freedom of movement of people, and a lack of autonomy when it came to striking new trade deals, making a mockery of the Brexit referendum result, according to May. A Canada-style deal, on the other hand, would amount to a trading relationship between the UK and the EU involving customs checks at the borders. In order to respect the Good Friday Agreement’s peace-promoting guarantee of no border between Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (part of the EU), however, that would mean that the customs checks would take place somewhere between Norther Ireland and the rest of the UK, undermining the country’s unity. It would also profoundly destabilize May’s government, which is propped up by the votes of MPs belonging to the DUP, a Northern Irish party, who would not tolerate such a solution.

The similarities with Greece’s negotiating strategy are striking.May seems to be engaged in a game of chicken. The assumption is that the EU would have just as much, if not more, to lose from a no-deal Brexit. Hence May’s mantra: “no-deal is better than a bad deal,” aimed at convincing the EU she is not afraid of the former. The similarities with Greece’s negotiating strategy are striking. After the 2015 elections, the leftist Syriza-led Greek government’s negotiation tactic to gain more favorable bailout terms was based on the assumption that if the sides couldn’t agree, Greece’s inevitable exit from the Eurozone would have been even more damaging for the EU than for Greece. The EU called Greece’s bluff, and the Greek government eventually capitulated.

May’s game of chicken will probably end in a similar way. The EU is unlikely to budge; 27 countries, speaking with one voice, and with less to lose in the case of no deal, are in a much stronger position than a single country, with a divided government, and which could face serious shortages with its EU trade disrupted. And even if the EU were to back down, accepting some version of Chequers, the deal would have to be approved by parliament. Labour and pro-EU Conservative MPs have said they would vote such a plan down. On the other hand, if May accepts a variation of the Canada-style trade deal on offer from the EU, the same MPs, including the DUP, will again probably reject it in parliament. This all makes a no-deal result seem rather likely. At that point, it is unclear how May’s government can continue, and a Conservative party leadership contest, a general election, or a second referendum, become plausible.

This brings us to the strategy of the opposition, the Labour party. Its plan is that if enough pro-EU Conservative MPs vote down the deal May brings to parliament, a general election could be triggered, which Labour assumes it would win. If that happens, the argument goes, Labour would proceed to renegotiate the terms of withdrawal from the EU, and get a better deal than May. This was in fact also Syriza’s and Tsipras’s plan when they ousted the prior government and came into power in January 2015. They believed that their fresh democratic mandate gave them the opportunity to start negotiations from scratch—only to be told by the EU that the Greek bailout was a national affair greater than any one party, and that the country was bound by what had already been discussed and agreed to.

A hypothetical Labour government in the UK would likely face a similar predicament. Labour would again have to choose between variations of the currently available options: staying in the EEA, or going for a Canada-style trade deal. More importantly, unless there was a pause to the withdrawal process, and the UK remained within the EU for longer than originally planned, there wouldn’t be enough time to re-negotiate. The Brexit date is March 29, and even if a general election took place in January, a couple of months are hardly enough time.

The UK is suffering from the same illusions as Greece was in its negotiations with the EU: overestimating its power, and believing that a shift in domestic politics, either by a change of government or Prime Minister, can yield a better result. Brexit, ironically, was sold by the likes of Johnson as a way for the UK to gain sovereignty and autonomy. It was also sold on the promise of continuing to trade with the EU as if nothing had changed—all that was needed was the right democratic mandate. Instead, what the UK is finding out is that in leaving the EU, it has much less say over its future than it did before. A single national democratic mandate is not all powerful against the interests of several other democracies organized together—a valuable lesson for those who advertise a return to national politics in a supranational era.

No comments :

Post a Comment